SYSTEMIC HYPERTENSION

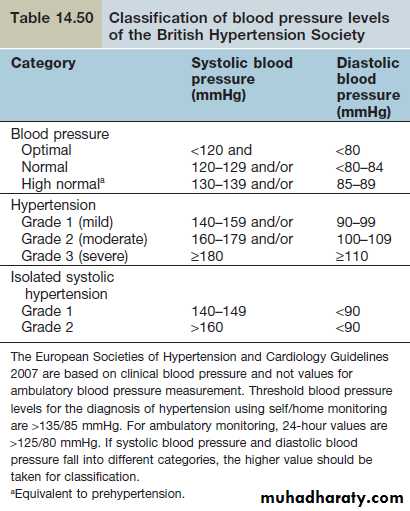

Definitions of hypertensionElevated arterial blood pressure is a major cause of premature vascular disease leading to cerebrovascular events, ischaemic heart disease and peripheral vascular disease. Blood pressure is a characteristic of each individual, like height and weight, with marked interindividual variation, and has a continuous (bell-shaped) distribution. The levels of blood pressure observed depend on the characteristics of the population studied – in particular, the age and ethnic background. Blood pressure in industrialized countries rises with age, certainly up to the seventh decade. This rise is more marked for systolic pressure and is more pronounced in men. Hypertension is very common in the developed world. Depending on the diagnostic criteria, hypertension is present in 20–30% of the adult population. Hypertension rates are much higher in black Africans (40–45% of adults). The definition of an abnormal blood pressure is indicated in Table 14.50.

The risk of mortality or morbidity rises progressively with increasing systolic and diastolic pressures, with each measure having an independent prognostic value; e.g. isolated systolic hypertension is associated with a two- to threefold increase in cardiac mortality. A prehypertension category has been added to reflect the continuum between normal and abnormal blood pressure. All adults should have blood pressure measured routinely at least every 5 years until the age of 80 years.

Measurement of blood pressure

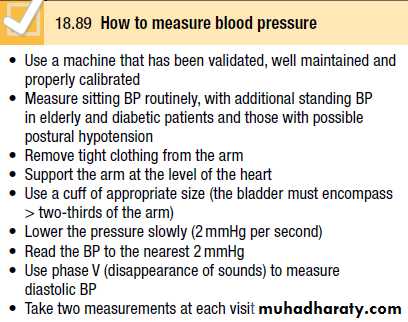

A decision to embark upon antihypertensive therapy effectively commits the patient to life-long treatment, so BP readings must be as accurate as possible. Measurements should be made to the nearest 2 mmHg, in the sitting position with the arm supported, and repeated after 5 minutes’ rest if the first recording is high (Box 18.89). To avoid spuriously high recordings in obese subjects, the cuff should contain a bladder that encompasses at least two-thirds of the circumference of the arm.

Home and ambulatory BP recordings

Exercise, anxiety, discomfort and unfamiliar surroundings can all lead to a transient rise in BP. Sphygmomanometry, particularly when performed by a doctor, can cause an unrepresentative surge in BP which has been termed white coat’ hypertension, and as many as 20% of patients with apparent hypertension in the clinic may have a normal BP when it is recorded by automated devices used at home. The risk of cardiovascular disease in these patients is less than that in patients with sustained hypertension but greater than that in normotensive subjects.A series of automated ambulatory BP measurements obtained over 24 hours or longer provides a better profile than a limited number of clinic readings and correlates more closely with evidence of target organ damage than casual BP measurements. However, treatment thresholds and targets must be adjusted downwards because ambulatory BP readings are systematically lower (approximately 12/7 mmHg) than clinic measurements. The average ambulatory daytime )not 24-hour or night-time) BP should be used to guide management decisions.

Patients can measure their own BP at home using arange of commercially available semi-automatic devices.

The value of such measurements is less well established and is dependent on the environment and timing of the readings measured. Home or ambulatory BP measurements are particularly helpful in patients with unusually labile BP, those with refractory hypertension, those who may have symptomatic hypotension, and those in whom white coat hypertension is suspected.

Causes

The majority (80–90%) of patients with hypertension have primary elevation of blood pressure, i.e. essential hypertension of unknown cause.

Essential hypertension

Essential hypertension has a multifactorial aetiology.

Genetic factors

Blood pressure tends to run in families and children of hypertensive parents tend to have higher blood pressure than age-matched children of parents with normal blood pressure.

Fetal factors

Low birth weight is associated with subsequent high blood pressure. This relationship may be due to fetal adaptation to intrauterine undernutrition with long-term changes in blood vessel structure or in the function of crucial hormonal systems.

Environmental factors

Among the several environmental factors that have been proposed, the following seem to be the most significant: Obesity. Fat people have higher blood pressures than thin people.

Alcohol intake. Most studies have shown a close relationship between the consumption of alcohol and blood pressure level.

Sodium intake. A high sodium intake has been suggested to be a major determinant of blood pressure differences between and within populations around the world. Populations with higher sodium intakes have higher average blood pressures than those with lower sodium intake. There is some evidence that a high potassium diet can protect against the effects of a high sodium intake.

Stress. While acute pain or stress can raise blood pressure, the relationship between chronic stress and blood pressure is uncertain.

Humoral mechanisms

The autonomic nervous system, as well as the reninangiotensin, natriuretic peptide and kallikrein-kinin system, plays a role in the physiological regulation of short-term changes in blood pressure and has been implicated in the pathogenesis of essential hypertension.

Insulin resistance

An association between diabetes and hypertension has long been recognized and a syndrome has been described of hyperinsulinaemia, glucose intolerance, reduced levels of HDL cholesterol, hypertriglyceridaemia and central obesity all of which are related to insulin resistance) in association with hypertension. This association (also called the ‘metabolic syndrome’) is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease.

Secondary hypertension

Secondary hypertension is where blood pressure elevation is the result of a specific and potentially treatable cause

Table ( 14.51(

Assessment

Management should be considered in three stages: assessment, non-pharmacological treatment and drug treatment.During the assessment period, secondary causes of hypertension should be excluded, target-organ damage from the blood pressure should be evaluated and any concomitant conditions (e.g. dyslipidaemia or diabetes) that may add to

the cardiovascular burden should be identified.

History

The patient with mild hypertension is usually asymptomatic. Attacks of sweating, headaches and palpitations point towards the diagnosis of phaeochromocytoma. Higher levels of blood pressure may be associated with headaches, epistaxis or nocturia. Breathlessness may be present owing to left ventricular hypertrophy or cardiac failure, while angina or symptoms of peripheral arterial vascular disease suggest the diagnosis of atheromatous renal artery stenosis. This is usually a local manifestation of more generalized atherosclerosis, and patients are often elderly with coexistent vascular disease . Fibromuscular disease of the renal arteries encompasses a group of conditions in which fibrous or muscular proliferation results in morphologically simple or complex stenoses and tends to occur in younger patients. Malignant hypertension may present with severe headaches, visual disturbances, fits, transient loss of consciousness or symptoms of heart failure.

Examination

Elevated blood pressure is usually the only abnormal sign. Signs of an underlying cause should be sought, such as renal artery bruits in renovascular hypertension, or radiofemoral delay in coarctation of the aorta. The cardiac examination may also reveal features of left ventricular hypertrophy and a loud aortic second sound. If cardiac failure develops, there may be a sinus tachycardia and a third heart sound.