PRACTICAL MEDICAL CHEMISTRY

First Class

BY

Prof. Dr. Amer A. Taqa

Assistants

Lecturer, Dr. Ammar A. Q. Alhamdani

Lecturer Mayada M. A. Alnoaimi

2017-2018

MOSUL UNIVERSITY

College of Dentistry

1

PRACTICAL MEDICAL CHEMISTRY

Introduction to the laboratory

SAFETY PROCEDURES

1. Chemical laboratory is a very dangerous workshop. Never work in the

laboratory alone.

2. Do not eat, drink, or smoke in the laboratory. Most chemicals are poisonous.

Safety goggles will be worn in the laboratory any time there is laboratory

work in progress by any student.

3. Remember that your neighbor could have any accident even though you,

yourself, are not doing lab work. 4. If chemicals are spilled on the skin,

immediately flush the skin with running water and call for the laboratory

instructor. If chemicals are spilled on the clothes, remove them and flush the

skin with water.5. Never smell a reaction mixture directly. Minimise your

exposure to chemical vapours.

4. In order to avoid cuts and lacerations, protect your hands with a towel when

inserting either glass tubing or thermometers into stoppers or thermometer

adapters. Fire-polish all glass tubing and stirring rods so that there are no

sharp edges. Report any cuts to the lab instructor so that the injury may receive

proper attention.

5. Restrict long hair in such a manner that it does not interfere with your work,

become caught in the equipment, or catch fire. 8. Work with noxious chemicals

in the hood. When in doubt, work in the hood, including rinsing equipment used

in measuring such materials.

6. Absorb escaping noxious gases in water or the suitable medium, or conduct

the experiment in the hood.

7. Never heat an enclosed system. Never close completely an assembly from

which a gas is being evolved. Have any equipment assembly checked by a lab

instructor if this is the first time you have used the assembly.

8. Ordinary rubber stoppers are never used on flasks containing organic solvents.

Organic solvents attack rubber and cause contamination of your product.

2

9. Avoid fire. Most organic solvents are flammable. Play it safe and treat all

organic materials as though they are flammable.

10. NEVER heat an organic solvent over a Bunsen burner. Know the location of fire

extinguishers, bucket of sand, safety showers, and fire blankets.

11. Never attempt to extinguish an electrical fire with water. Use only

extinguishers designated for this purpose. Report any fire regardless of how

minor to the lab instructor. Report any burns to the lab instructor so that proper

treatment may be administered.

12. Avoid explosions. Never pour water into concentrated sulphuric acid. Always

add concentrated sulphuric acid slowly to water. Never mix a strong oxidising

agent with a strong reducing agent.

13. Never mix nitric acid with alcohol. Never heat a flask to dryness when distilling

or evaporating solvents. Small amounts of impurities that can be explosive will

be concentrated to dangerous levels.

Always know what your neighbours are doing, be prepared for any accident.

3

REAGENTS IN THE LABORATORY

Pure chemical reagents or solutions of chemical reagents are stored in labelled

bottles or dropping bottles in a convenient location in the laboratory. It is very

important to keep these reagents uncontaminated. Please obey the following rules

in using these reagents.

1. Read the labels carefully. Not only will the experiment be unsuccessful, but a

serious

accident

may

result

if

the

wrong

chemical

is

used.

2. Reagent bottles must be protected from contamination. You must therefore

never put spatulas, stirring rods, pipettes, or anything else into a reagent bottle.

Try to avoid taking a large excess of the reagent. However, if you should err

and take more than you need, do not return the excess to the bottle.

In other words, you only remove material from the reagent bottle, you

never put anything into it.

3. Never take the reagent bottles to the sink or to your desk. Put the bottles

back to the reagent shelf after using them.

4. Do not lay stoppers on the desk or shelf in such a way that they will become

contaminated. Depending on the shape of the stopper, either hold it while the

material is being removed or lay it on its flat top.

5. Glass stoppers that are stuck can generally be loosened by gently tapping

the stopper on the edge of the shelf.

6. The reagent area must be kept clean. Be sure that you clean up any chemicals

you spill.

7. If you empty a container, take it to be refilled, as directed by your instructor.

Do not return it to the reagent shelf empty.

8. Dispose the solid wastes in designated containers. Many kinds of liquid wastes

must be collected and handled separately. Ordinarily acids, bases, and most

inorganic

liquid

wastes

can

be

flushed

down the sink with copious amounts of cold water. Check the directions

for disposal of liquid wastes before using the sinks.

4

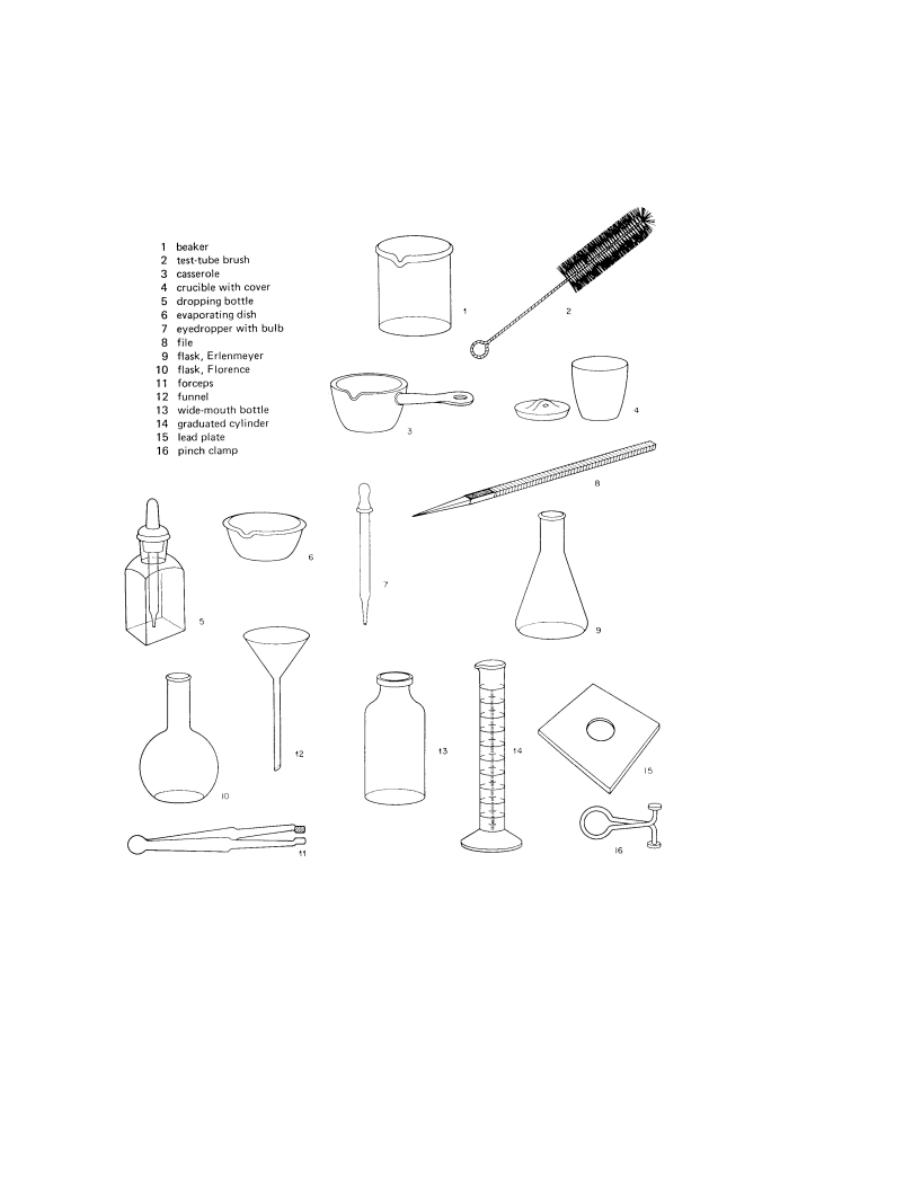

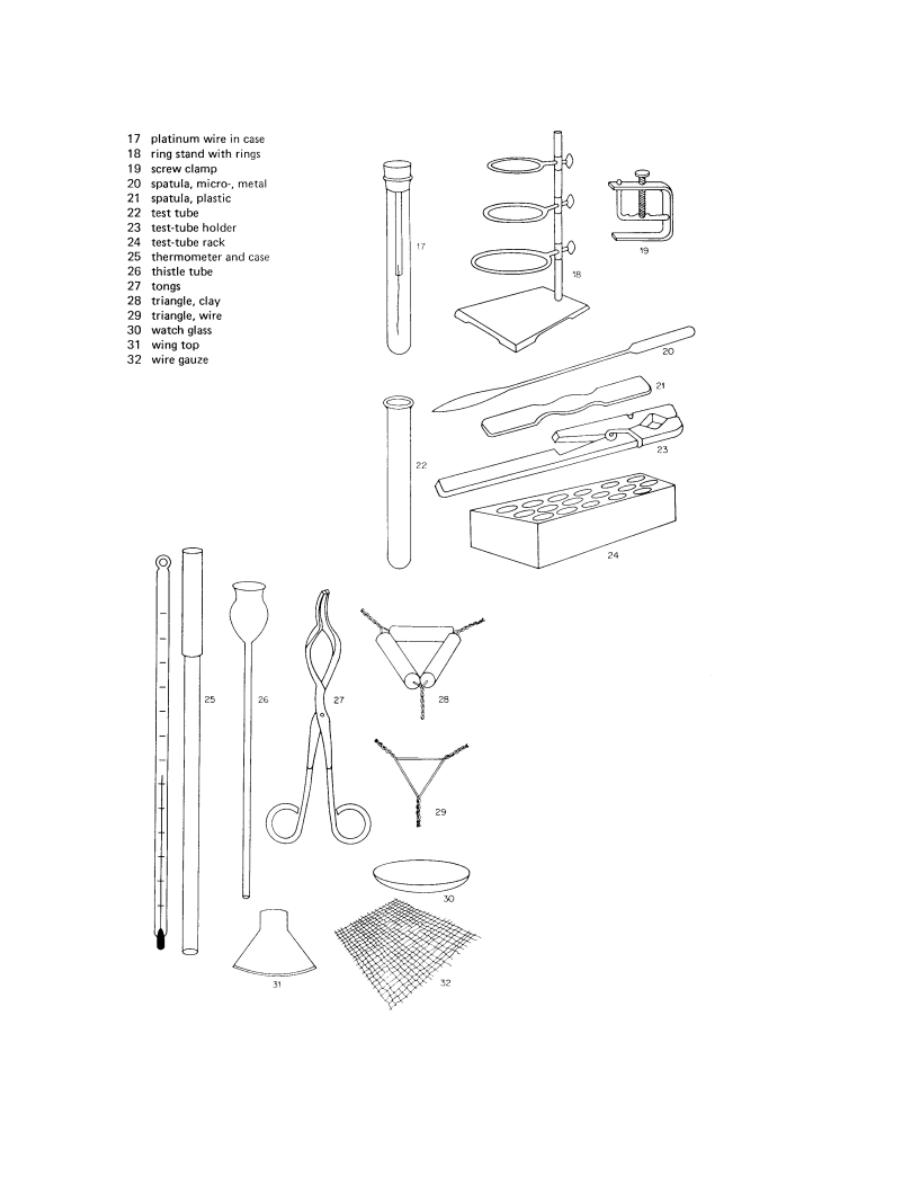

MOST COMMON LABORATORY EQUIPMENTS

5

6

EXPERIMENTAL ONE

RECRYSTALLIZATION

OBJECTIVE

1. To learn and apply the technique of recrystallization for the purification of a

crude or impure organic substance

.BACKGROUND

Recrystallization is the most convenient technique for purifying organic solids, if it

is feasible. It is based on the principles of solubility. In general, compounds

(solutes) are more soluble in hot liquids (solvents) than cold liquids. If a saturated

hot solution is allowed to cool, the solute is no longer soluble in the solvent and

forms crystals of pure compound which can be separated from the dissolved

impurities by filtration. Since the choice of solvent for recrystallization is often not

specified and is seldom obvious, testing by trial and error on a small scale is

generally required. Typically, a small amount (ca. 100 mg) of the substance to be

7

purified is placed in a small test tube and then 1 to 2 ml of the solvent to be tested

is added. If the solid dissolves cold, that solvent is obviously unsuitable. If the solid

mixture is largely insoluble in the cold solvent, the mixture is

warmed to its boiling point. If the material then dissolves, and reprecipitates on

cooling, the solvent is a good candidate for the recrystallization procedure.

Sublimation

Another possible complication in melting-point determinations occurs if the sample

sublimes. Sublimation is the change that occurs when a solid is transformed

directly to a gas, without passing through the liquid phase [see Technique 16]. If

the sample in the capillary tube sublimes, it can simply disappear as it is heated.

Many common substances sublime, for example, camphor and caffeine.

You can determine their melting points by sealing the open end of the capillary

tube in a Bunsen burner flame before it is placed in the melting-point apparatus.).

Decomposition

Some compounds decompose as they melt, a behavior usually indicated by a

change in color of the sample to dark red or brown. The melting point of such a

compound is reported in the literature with the letter d after the temperature. For

example, 186°C d means that the compound melts at 186°C with decomposition.

Sometimes decomposition occurs as a result of a reaction between the compound

and oxygen in the air. If this is the case, when the air is evacuated from the

capillary tube and the tube is sealed, the melting point can be determined without

decomposition. Place the sample in the capillary tube as directed earlier. Punch a

hole in a rubber septum, insert the closed end of the capillary tube through the

inside of the septum, then gently push most of the capillary through the septum. Fit

the septum over a piece of glass tubing that is connected to a vacuum line. Turn on

the vacuum source, and while heating the upper portion of the capillary tube in a

Bunsen burner flame, hold and pull on the sample end of the capillary tube until it

seals.

RECRYSTALLIZATION

A pure organic compound is one in which there are no detectable impurities.

Because experimental work requires an immense number of molecules

(Avogadro’s number per mole), it is not true that 100% of the molecules in a

“pure” compound are identical to one another. Seldom is a pure compound purer

8

than 99.99%. Even if it were that pure, one mole would still contain more than

1019 molecules of other compounds. Nevertheless, we want to work with

compounds that are as pure as possible, and recrystallization is one of the major

techniques for purifying solid compounds.

What Is Recrystallization?

When a crystalline material (solute) dissolves in a hot solvent and then returns to a

solid again by crystallizing (precipitating) in a cooled solvent, the process is called

recrystallization. Its success depends on the increasing solubility of the crystals in

hot solvent and their decreasing solubility when the solution cools, thereby causing

the compound to recrystallize. Impurities in the original crystalline material are

usually present at a lower concentration than in the substance being purified. Thus,

as the mixture cools, the impurities tend to remain in solution while the highly

concentrated product crystallizes.

MELTING POINTS AND MELTING RANGES

Molecules in a crystal are arranged in a regular pattern. Melting occurs when the

fixed array of molecules in the crystalline solid rearranges to the more random,

freely moving liquid state. The transition from solid to liquid requires energy in the

form of heat to break down the crystal lattice. The temperature at which this

transition occurs is the solid’s melting point, an important physical property of any

solid compound. The melting point of a compound is useful in establishing its

identity and as a criterion of its purity.

Until the advent of modern chromatography and spectroscopy, the melting point

was the primary index of purity for an organic solid. Melting points are still used as

a preliminary indication of purity.

9

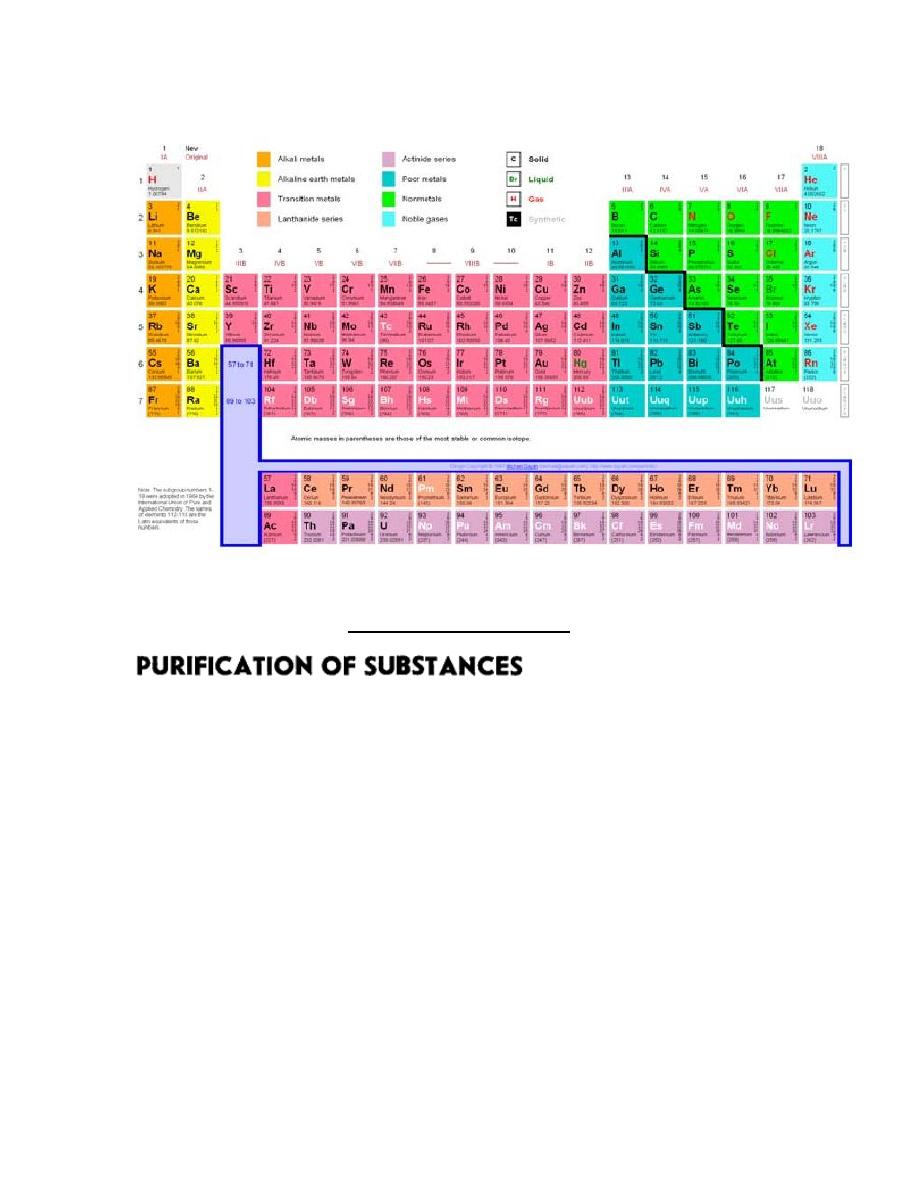

Common solvents for crystallization

Sometimes no single solvent is suitable and two miscible solvents can be combined

to produce a suitable solvent. In this experiment, solvent selection for

crystallization of known compounds will be performed. Then an unknown sample

will be purified by crystallization

Solvent selection

1. Place each of 10 finely crushed known samples, the size of half a grain of rice, in

6 test tubes.

2. Add 5 drops of water, 95% ethanol, ethyl acetate, acetone, toluene and hexane to

test tubes No.1- 6, respectively. Swirl the content in each tube and note whether the

sample is soluble in the solvent at room temperature. Observe and record the

observations.

3. Warm the test tubes containing insoluble sample in the conical well of the heat

dissipation block on hot plate. Swirl the content in each tube and note whether the

sample is soluble in hot solvents. Observe and record the observations.

: Be careful not to leave the solution heating without attention.

4. Let the solution cool and observe the crystals form.

5. Record each solvent tested and indicate which of the six solvents is the best

solvent suited for crystallization of each known sample.

10

6. Select the suitable solvent for recrystallization of an unknown sample, according

to the above procedures. Record the observations and the most suitable solvent for

recrystallization.

Recrystallization of an unknown sample

7. Place 100 mg (accurately weigh) of the unknown sample for crystallization into

5-mL conical bottom flask. Add 1 mL of the suited solvent.

8. Heat the mixture to a gentle boiling and often swirl the solution until the solid is

all dissolved. : Be careful not to allow bumping which will cause a possible loss

of material from the flask.: If necessary, add 10 mg of activated carbon and

reheat boiling for a few minutes to decolorize the solution.Note the solution cool

down slightly before adding the activated carbon.

9. If the solid does not dissolve completely, add a few portions of 0.1 mL solvent

and continue heating.

10. Observe at every addition whether any more solid dissolves. If not, it may be

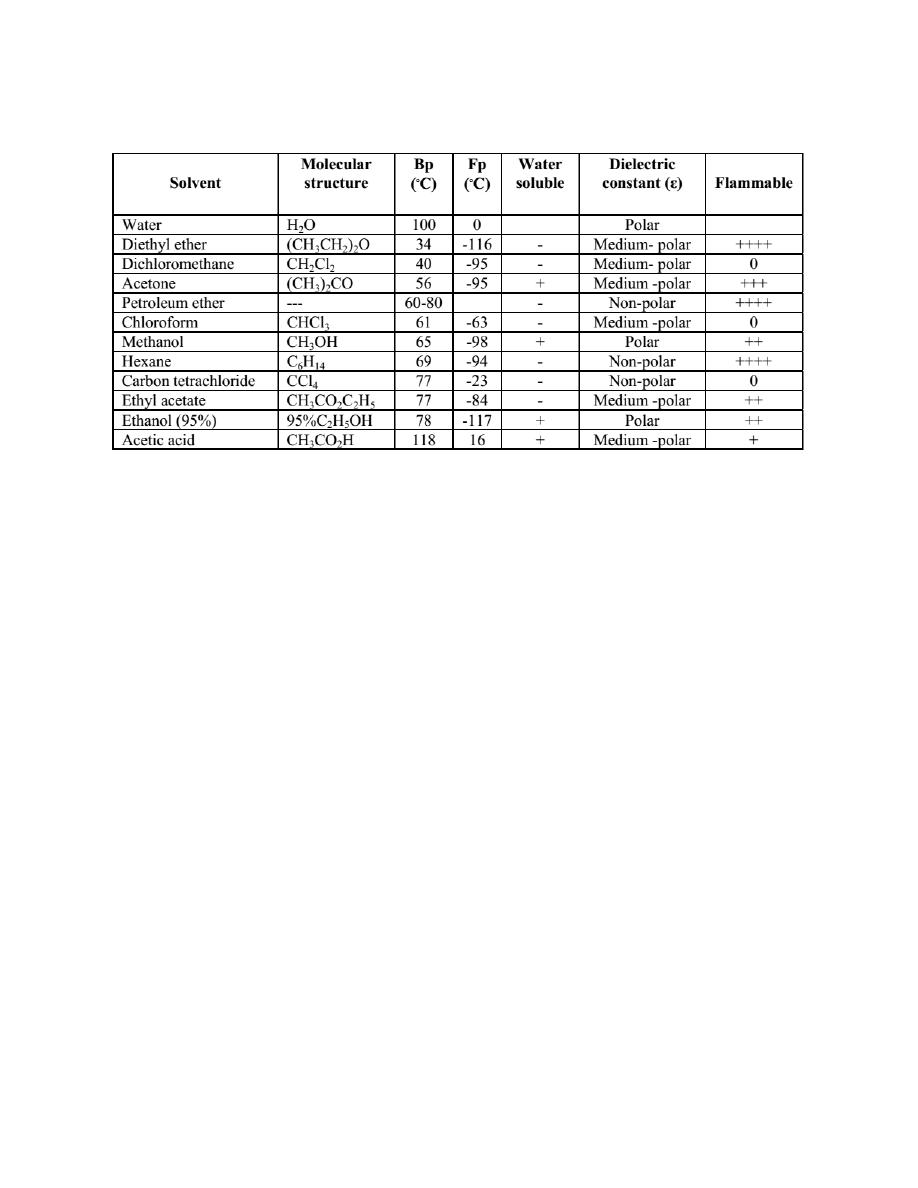

due to impurities. Filter the hot solution through a Pasteur filtering pipette to

remove insoluble impurities or activated carbon. : If no activated carbon has been

added or no undissolved particles are in the solution,this step should be omitted.

11. Put the stopper on the flask. Allow the filtrate cool down. After the solution has

come to room temperature, carefully set in an ice-water bath to complete the

crystallization process.: Do not disturb the solution. Slow cooling gives the best

crystals.

12. In case of mixed-solvent crystallization, reheat the solution to boiling and add

the first solvent dropwise until the boiling solution remains cloudy or precipitate

forms.

Then add a drop of second solvent to restore the clear solution. Remove the flask

from the heat, put the stopper on the flask. Allow the solution to cool to room

temperature.

: If no crystallization occurs after the solution has cooled, it indicates either too

much

solvent has been used or that the solution is supersaturated. The crystallization

can be induced by adding a crystal of the original solid in a supersaturated

solution. If no solid is available and a volatile solvent is being used, immerse the

tip of a glass rod or metal spatula in the solution for a few seconds. The crystals

11

that form at the end of the rod or spatula are then added into the solution to

initiate crystallization.

13.Rinse the crystals with a small portion of cool solvent, and continue suction to

air dry.

14. Weigh the crystal and calculate percent recovery. Determine the melting point

and

record.

Use of Freezing Mixtures in Crystallization.—It often happens that substances

which do not separate from their hot solutions when the latter are cooled with

water, crystallize out well when the solutions are allowed to stand for some time in

a freezing mixture. For this purpose, a mixture consisting of equal weights of

sodium chloride and finely divided ice or snow, is commonly used; with snow, a

temperature of -17° is obtained.

12

A mixture of equal weights of crystallized calcium chloride and snow gives the

temperature -48°. A convenient freezing mixture is made by covering finely

divided ice with commercial concentrated hydrochloric acid.

MIXTURES AND COMPOUNDS

WE now proceed to the more purely chemical parts of our study, and must first try

to form clear ideas as to what is meant by a chemical compound and how we

distinguish it from a mixture. Mix together about equal quantities of sugar and sand

: taste a little of the mixture how are the properties of the mixture related to those of

the ingredients ? (a) How can you separate the sugar from the sand ? can you pick

out any bits of sugar or sand with your fingers ? Rub some of the mixture in a

mortar can you separate the sugar and sand now? (b) Put what you have powdered

in the mortar into a beaker, add water and stir well or heat on the sand-bath; what

happens? How can you separate the solution of sugar from the insoluble sand?

Take a piece of filter paper, fold it as shown in Fig. I 5, then put it in a funnel and

fit the paper carefully to the sides of the funnel ; place the funnel in the mouth of a

flask and now pour the contents of the beaker into the FIG. 15. Folded Filter Paper,

funnel, taking care not to let the liquid fill the funnel up to the top of the filter

paper. What is the result? (c) Mix some salt and chalk: taste a little; how do the

properties of the mixture compare with those of the ingredients? Separate them in

the same way as before; is the separation complete? Try this by taking a weighed

quantity of salt and

13

of chalk (both should be dry), mixing, and then separating as before

; dry the funnel with the chalk and filter paper in a steam-oven, then weigh the

chalk and the filter paper (but without the funnel), putting an equal piece of filter

paper in the other pan of the balance so as to get the weight of the chalk itself. To

find the weight of the salt, take a weighed evaporating dish, put the solution of salt

into it (or if there is too much, .Filtering. much liquid put in only part at first and

afterwards add more) and evaporate it to dryness on the sand-bath. Let the dish cool

and weigh it with the salt. How does the weight of salt obtained compare with the

amount used?

(d) Mix some fine iron-filings with about twice the weight of flour of sulphur:

examine the properties of the mixture; is it attracted by a magnet like iron, and

will it burn like sulphur? Try to separate the iron and sulphur again (i) by the

magnet,(2) by shaking with water. You find that neither the iron nor the sulphur

will dissolve in the water, but other liquids could be used to separate the sulphur by

dissolving it, just as the salt and sugar were separated by solution in water; such a

liquid is carbon disulphite, but its use by a class is dangerous and objectionable on

account of its inflammability and bad smell. (e) Put a little of the dry mixture of salt

and chalk in a test tube and heat it for a few minutes in the flame of your burner ;

let it cool, then shake out the contents and examine them to see whether any change

has occurred.

14

EXPERIMENTAL TWO

Distillation.

You have seen in several of the preceding experiments that when a solution of a

solid in water is evaporated, the solid is left behind: we have also found that the

steam given off carries none of the solid with it, for in Exercise. (c) the amount of

salt left was equal in weight to that used. It is plain that by condensing the steam

15

given off we shall get water free from the solid impurities dissolved in it, provided

they behave like salt and do not evaporate along with the steam.

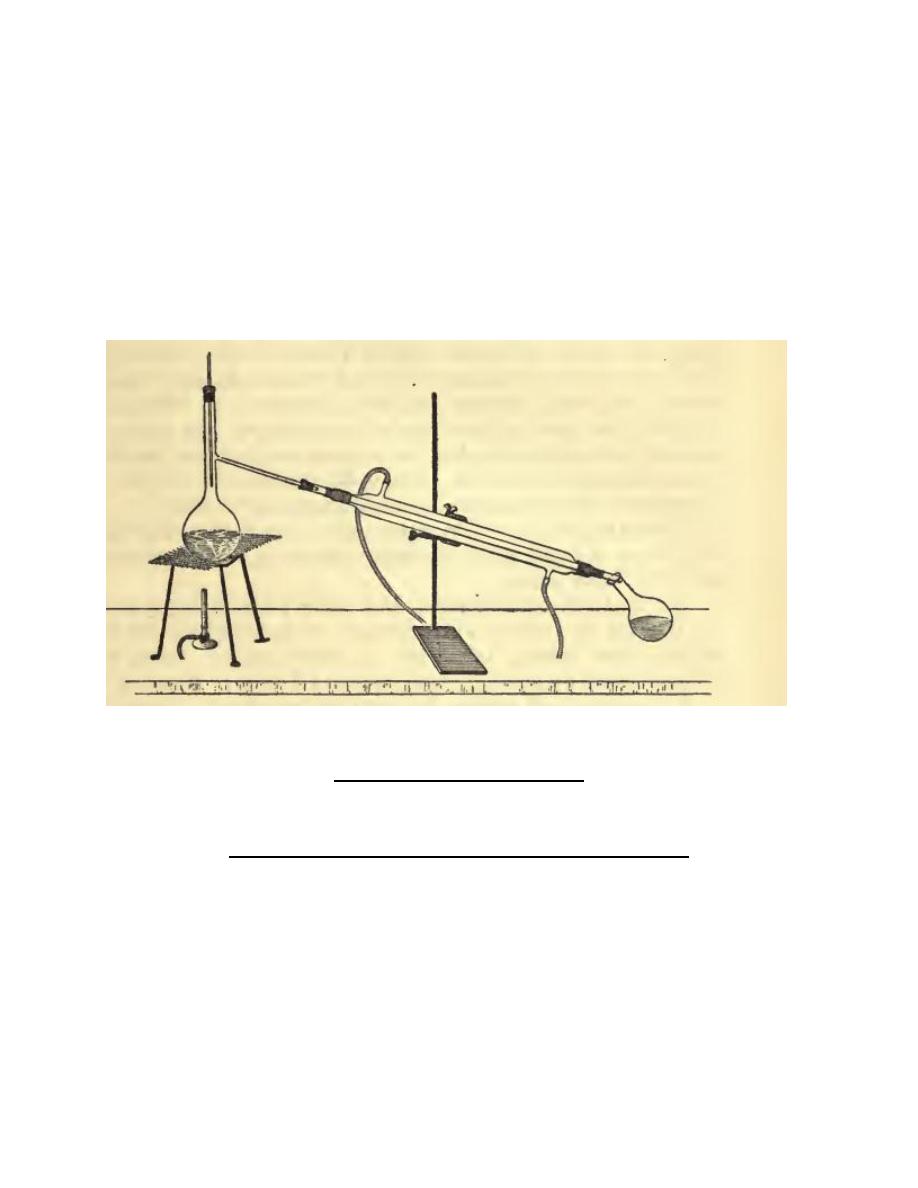

(a) Fit a 600 cc. flask with a good cork and a bent piece of fairly wide glass tubing

; it is best to have the end of the tube which is inside the flask ground aslant ; the

tubing should be chosen of such a size as to go readily, but with not much to spare,

into the inner tube of a Liebig's condenser, and the joint can then easily be made

sufficiently airtight by means of a strip of clean glazed paper wrapped round the

smaller tube ;fill the flask about half full of water, and add a few crystals of

potassium permanganate, which will colour the water intensely purple. Heat the

flask on wire gauze or a sand-bath ; connect the lower side-tube of the condenser

with the tap, and the upper side-tube to the sink : turn on the tap gently until the

outer jacket of the condenser is full and water issues steadily from the waste tube.

Collect the condensed water in a flask or beaker. Test this water does it contain any

of the potassium permanganate ? (b) Repeat the experiment, using water to which

some strong ammonia solution has been added in place of water coloured with

potassium permanganate. Collect the distillate in several portions and test each of

them by smell for the presence of ammonia : if a more sensitive test than the sense

of smell is wanted, you may use paper coloured red with litmus, which you will

find on trial is turned blue by ammonia.

Fractional Distillation.

This last experiment will have shown that it is sometimes difficult to purify water

by distillation from a volatile impurity ; the separation can, however, generally be

effected more or less completely in such a case by the process known as fractional

distillation .

Mix equal volumes of water and methylated spirit, and put the mixture in a 200 cc.

distillation flask of the kind shown in Fig. 33. In the neck of the flask fit a cork,

through which passes a thermometer whose bulb should be FIG.

Fractional Distillation.

just below the opening of the side tube ; a cork will be needed to connect this side

tube with the condenser. Heat the flask on wire gauze, and collect the distillate in

two approximately equal portions; test these by trying whether a little of each will

burn, also by taking their specific gravities with a hydrometer. Which contains

more alcohol? Empty the distillation flask, then pour back into it the first half A of

the distillate: distil until half of A has been collected, and test this by taking its

16

specific gravity. Compare the numbers obtained with the specific gravity of the

methylated spirit itself. What do you find ? Notice also the temperatures indicated

by the thermometer throughout the distillation. What do you conclude as to the

boiling point of methylated spirit ? Then try the next experiment.

Empty the distillation flask, and pour in some undiluted methylated spirit ; heat

this to boiling and notice carefully the temperature indicated by the thermometer

during the distillation. Has methylated spirit a constant boiling point ? If not, you

may conclude that it is not a single substance, but a mixture of two or more.

EXPERIMENTAL THREE

Physical and Chemical Properties of Hydrocarbons

CHEMISTRY OF HYDROCARBON

Background:

In this experiment you will observe the solubility (a physical property) and

the chemical reactivity of three different groups of hydrocarbons: alkanes, alkenes

and aromatic compounds.

17

Hydrocarbons are organic compounds that contain only carbon and

hydrogen. They are extremely important to our society because so many products

are derived from them: fuels, fabrics, plastics, antifreezes, anesthetics, insecticides,

to name a few. The major source of aliphatic hydrocarbons is petroleum, an

extremely complex mixture of compounds. Each of us, on the average, uses

several tons of petroleum each year (directly or indirectly), mostly for fuel.

Aromatic hydrocarbons are mainly obtained from coal, although small amounts are

also obtained from petroleum.

The solubility of a substance (the solute) in a solvent is the most important

chemical principle underlying three major techniques you will study in the organic

chemistry laboratory: crystallization, extraction, and chromatography. Solubility

can generally be predicted based on the “like dissolves like” rule. This means that

polar compounds dissolve in polar solvents and nonpolar compounds dissolve in

nonpolar solvents. This rule works because solubility is based on intermolecular

forces, and these forces can occur between molecules of the same compound, or

between molecules of different compounds. So, compounds with similar

intermolecular forces will form solutions. Recall that polar compounds have

dipole-dipole interactions, while nonpolar compounds have dispersion forces,

which are much weaker. When discussing a liquid being mixed with another liquid

(as in this experiment), it is sometimes more appropriate to say that the compound

and the solvent are miscible. Likewise, if the liquid organic compound is insoluble

in the solvent, then they are immiscible. You will test the solubility of the three

types of hydrocarbons in water and in dichloromethane.

Each of the three classes of hydrocarbons has different chemical reactivity.

Alkanes are relatively unreactive because they have strong, nonpolar covalent

bonds. Also, since they are already completely saturated, they can’t undergo

addition reactions. Aromatic hydrocarbons are also relatively unreactive, but for a

different reason. They have a special stability due to resonance (their pi electrons

are completely delocalized). Aromatic compounds do not undergo addition

reactions, because they would lose this special stability. Alkenes, however, are

much more reactive than the other two classes. They have electron-rich double

bonds (their pi electrons are not completely delocalized, even in conjugated

alkenes) that allow them to easily undergo addition reactions.

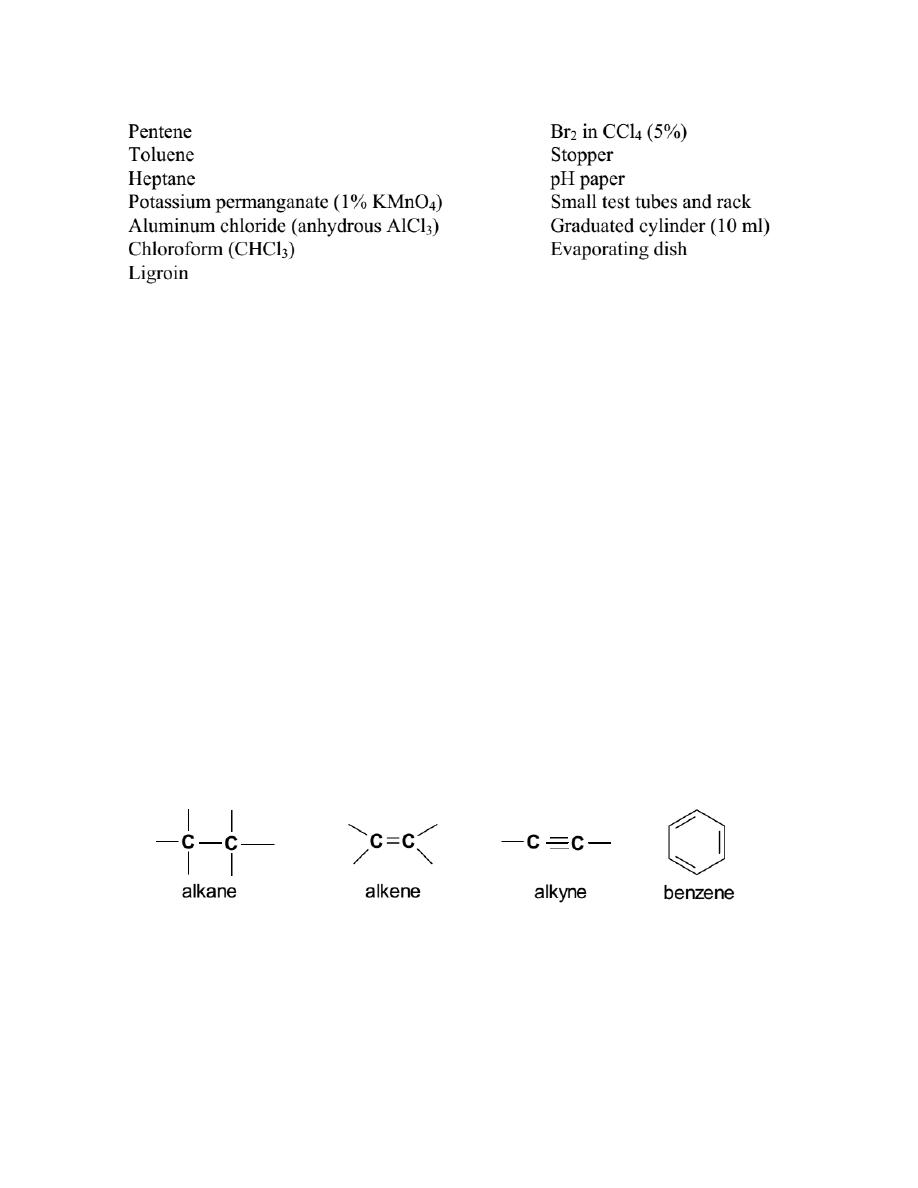

EQUIPMENT AND CHEMICALS

BJECTIVE The objective of this experiment is to distinguish the difference

between various types of hydrocarbons by performing simple tests and reactions

involving hydrocarbons.

18

- DISCUSSION Organic chemistry is the study of compounds containing

carbon (excluding CO2, CO, carbonates, elemental carbons, and others). The

two primary sources of organic compounds are oil and coal. Other sources of

organic compounds are plants, animals, and microorganisms. Hydrocarbons

are organic compounds that contain only carbon and hydrogen. There are

various classifications of hydrocarbons. To study the chemical and physical

properties of hydrocarbons.

In this experiment you will test the reactivity of the three types of

hydrocarbons with bromine, and with potassium permanganate. These are two

common classification tests for hydrocarbons. Bromine only reacts with alkanes or

aromatic hydrocarbons under special conditions. However, bromine reacts readily,

and rapidly, with alkenes to produce dibromoalkanes. A successful reaction is

indicated when the reddish-brown bromine is used up and colorless products are

formed (see below). Potassium permanganate is an oxidizing agent that can react

with alkenes to form diols, but does not react with alkanes or with aromatic rings.

It can react with alkyl substituents on aromatic rings, but only under very vigorous

conditions (high temperature etc.) A successful reaction will produce a brown

precipitate (MnO

2

), and the purple color of the potassium permanganate will

disappear (see below).

Hydrocarbons can be further divided into saturated hydrocarbons that have only

single carbon-carbon bonds (alkanes), and unsaturated hydrocarbons that have

multiple carbon-carbon bonds (alkenes, alkynes, aromatics). Most of the aliphatic

compounds are named based on the first ten alkanes (Table 14-1). As a rule,

hydrocarbons with names ending in -ANE are alkanes, -ENE are alkenes, and -

YNE are alkynes.

19

PROCEDURE

PART A - SOLUBILITY OF HYDROCARBONS The solubility of pentene,

toluene, heptane, and an unknown will be tested in various solvents. 1. Put 5 ml of

water (a polar solvent) into four different small test tubes. Label each test tube as

pentene, toluene, heptane, or unknown. 2. Add 1 ml of each hydrocarbon to their

respective test tubes. Stopper and shake. 3. The absence of two distinct liquid

layers indicates solubility (a cloudy appearance indicates insolubility). Record your

observations on the Report Sheet. 4. Add 5 ml of ligroin (non-polar solvent made

of saturated hydrocarbons) to four additional small test tubes. 5. Add 1 ml of each

hydrocarbon to its respective test tube. Stopper and shake. Record your

observations on the Report Sheet. 6. Remember the old saying - like dissolves like.

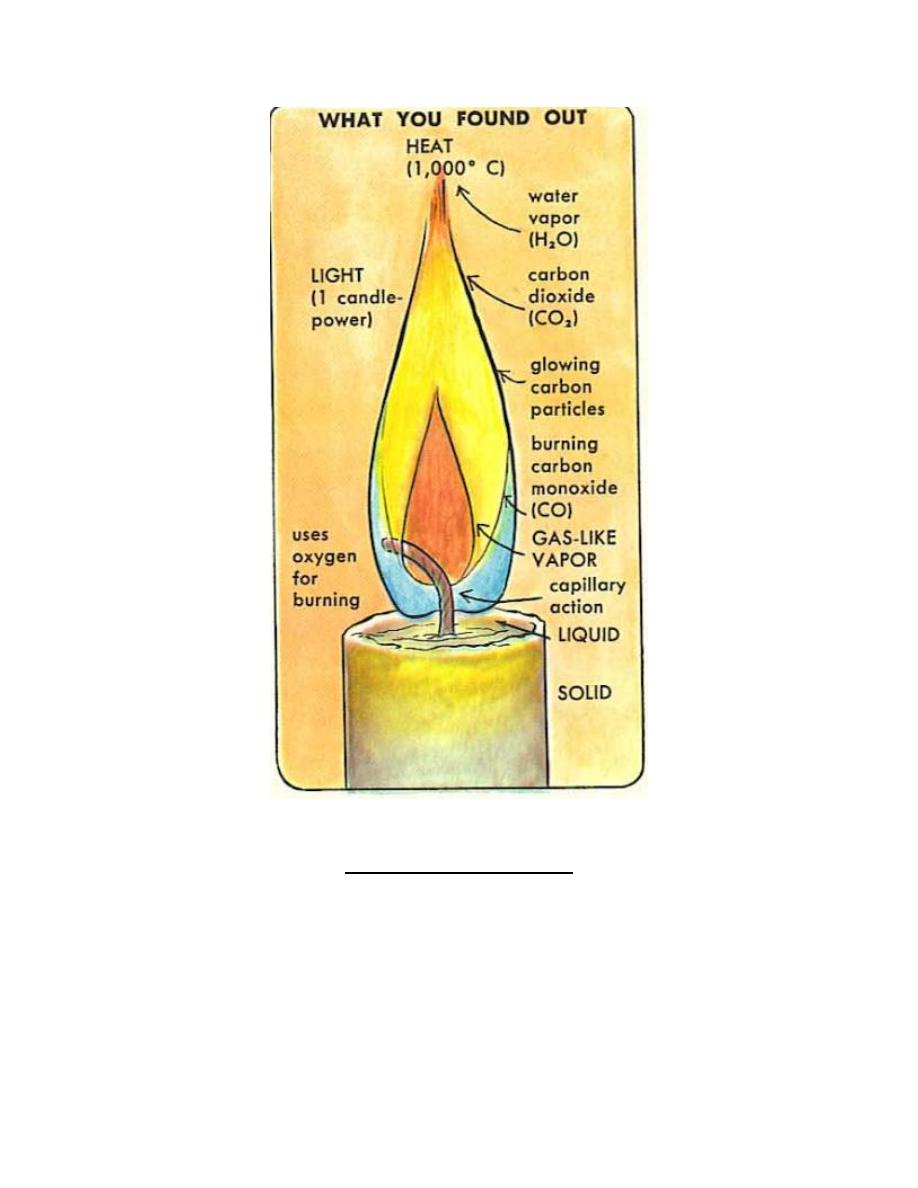

PART B - FLAMMABILITY OF HYDROCARBONS The combustion of the

heptane, pentene, toluene, and an unknown with oxygen will be observed. 1. Place

1 ml of heptane in an evaporating dish and ignite with a burning wood splint.

Record your observations on the Report Sheet. 2. Place 1 ml of pentene in an

evaporating dish and ignite. record your observations on the Report Sheet. 3. Place

1 ml of toluene in an evaporating dish and ignite. Record your observations on the

Report Sheet. 4. Place 1 ml of unknown in an evaporating dish and ignite. Record

your observations on the Report Sheet.

PART C - REACTION OF HYDROCARBONS WITH BROMINE The

reaction of pentene, heptane, toluene, and an unknown with bromine will be

observed. Bromine is brownish and the disappearance of the brown from a reaction

mixture indicates a reaction is taking place (positive test). 1. Clean and dry four

small tubes. 2. Place 1 ml of pentene in the first test tube, 1 ml heptane in the

second test tube, 1 ml of toluene in the third test tube, and 1 ml of the unknown in

the fourth test tube. 3. Carry out this next step in a fume hood. 4. Add 4 drops of

5% bromine in CCl4 to each test tube and gently swirl the contents of the tubes. 5.

Every 30 seconds place a piece of moistened blue litmus paper to the lip of each

test tube and blow gently into the test tube. If the blue changes to red, it indicates

the presence of HBr being given off in the reaction. Report your results on the

Report Sheet. 6. Observe any colour changes and the speed of the changes for five

minutes.

Record

these

observations

on

your

Report

Sheet.

PART D - REACTION OF HYDROCARBONS WITH POTASSIUM

PERMANAGANATE Potassium permanganate (KMO4) is an oxidizer. KMO4 is

a purple coloured compound. If the KMnO4 reacts with the hydrocarbon, a brown

colour will be observed (MnO2). This is known as the Baeyer Test for unsaturation.

1. Place 1 ml of each of the hydrocarbons (heptane, pentene, toluene, and the

unknown) into separate clean and dry small test tubes. 2. Add 3 drops of 1%

20

aqueous KMnO4 to each test tube, swirl gently, and let stand. 3. Record your

observations on the Report Sheet.

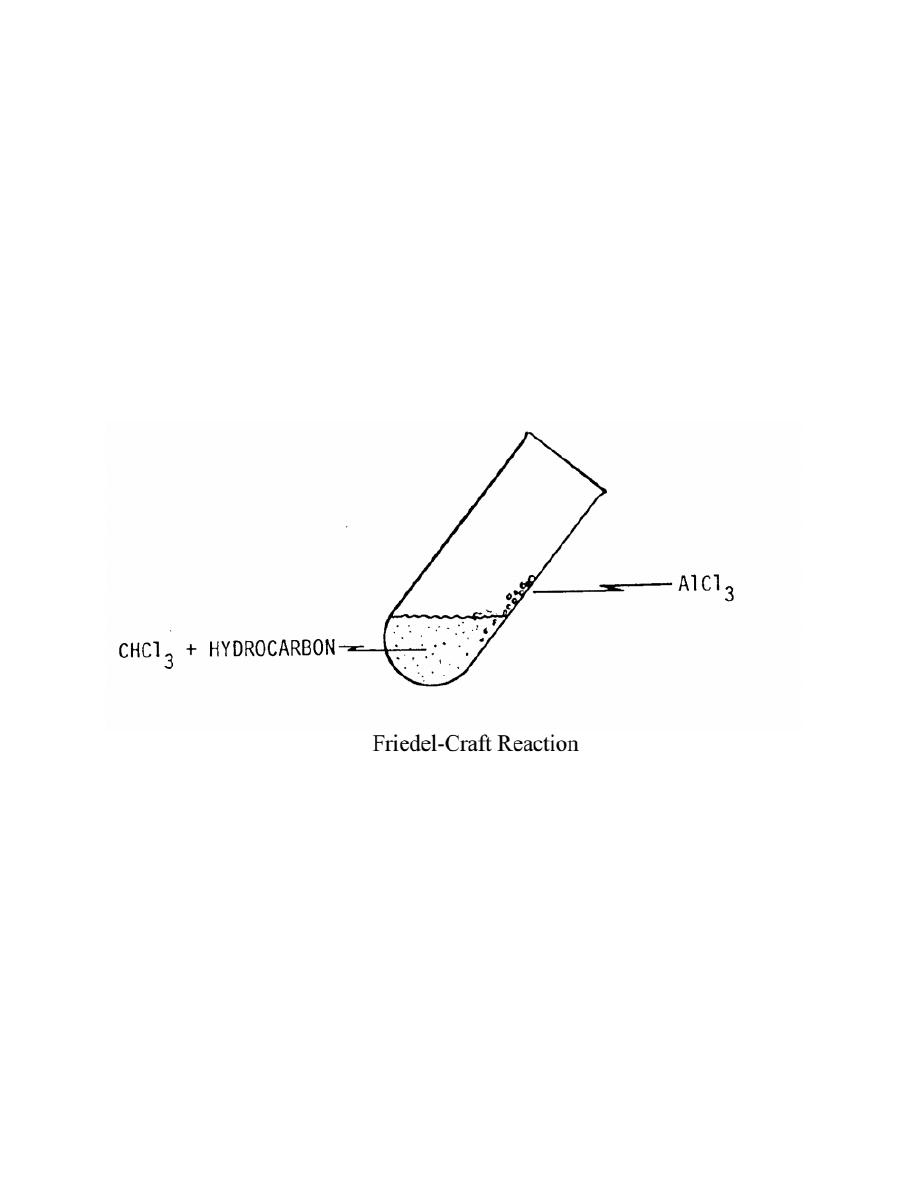

PART E - REACTION OF HYDROCARBONS WITH ALUMINUM

CHLORIDE The reaction of aromatic hydrocarbons with aluminum chloride

(AlCl3) and chloroform (CHCl3) to produce a brightly coloured compound is

known as a Friedel-Crafts reaction. 1. Place 2 ml of CHCl3 into four separate clean

and dry small test tubes. 2. Add two drops of pentene to one test tube, two drops of

heptane to the second test tube, two drops of toluene to the third test tube, and two

drops of the unknown to the fourth test tube, and gently swirl each test tube. 3.

Incline each test tube to moisten the wall and add 0.5 gm of AlCl3 so that some of

the solid strikes the side of the moisten test tube wall. 4. Record your observations

on the Report Sheet.

21

EXPERIMENTAL FOUR

Properties of Alcohols and Phenols

The functional group we are considering in this experiment is the hydroxy (or

hydroxyl) functional group, -OH. This group shows up in a number of guises in

organic compounds. Some of the common ones are shown in the table below.

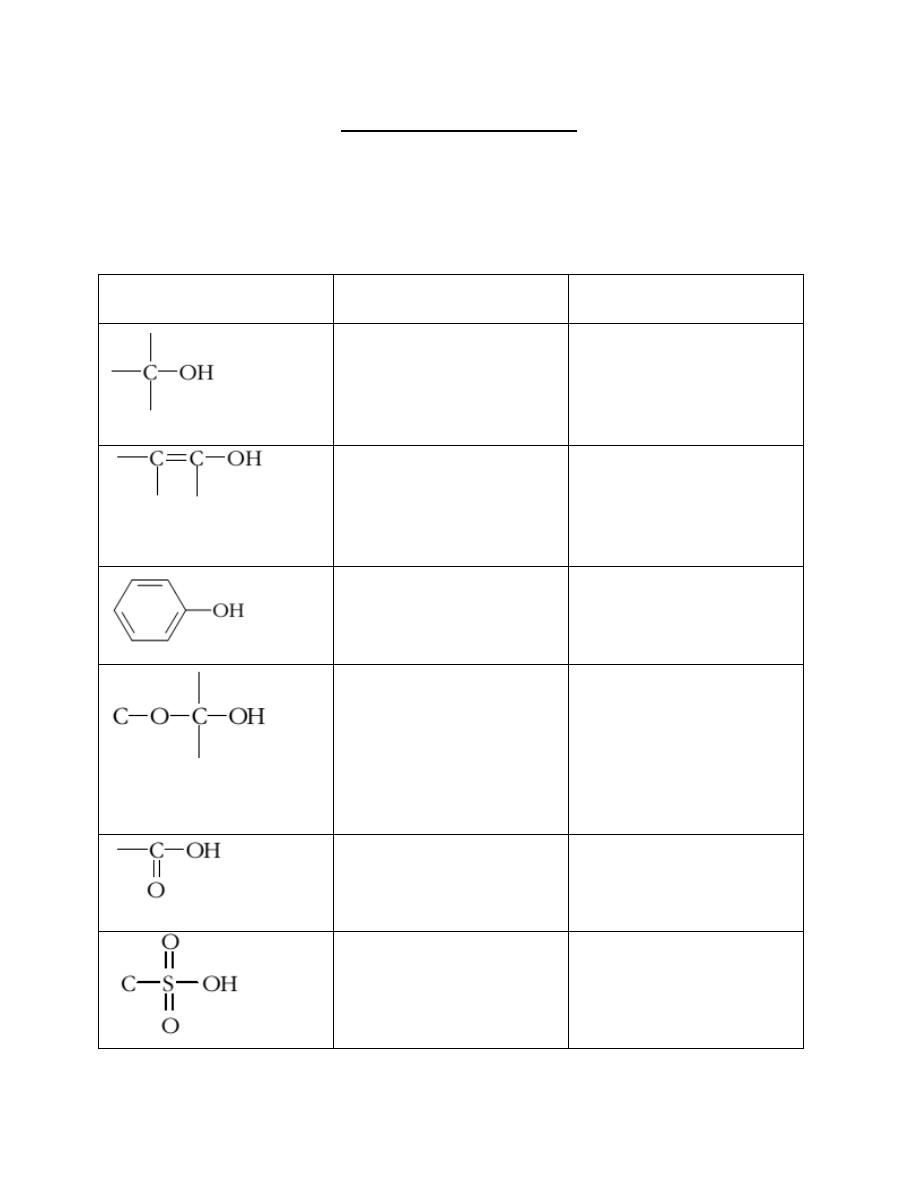

Functional

Group

Structure

Compound

Generic

Name

Comments

Alcohol

In an alcohol, the -OH is

attached to a tetrahedral

carbon

atom.

Very

weekly

acidic.

enol

Two functional groups

attached to the same

carbon. It’s an alkene and

an

alcohol.

Usually

unstable.

phenol

-OH directly bonded to

an

aromatic ring. Weekly

acidic.

Two functional groups

attached to the same

carbon.

Formed

from

reaction

between

an

alcohol and an aldehyde

or

ketone.

carboxylic acid

Two functional groups

attached to the same

carbon.

Moderately

acidic.

sulfonic acid

Very acidic.

22

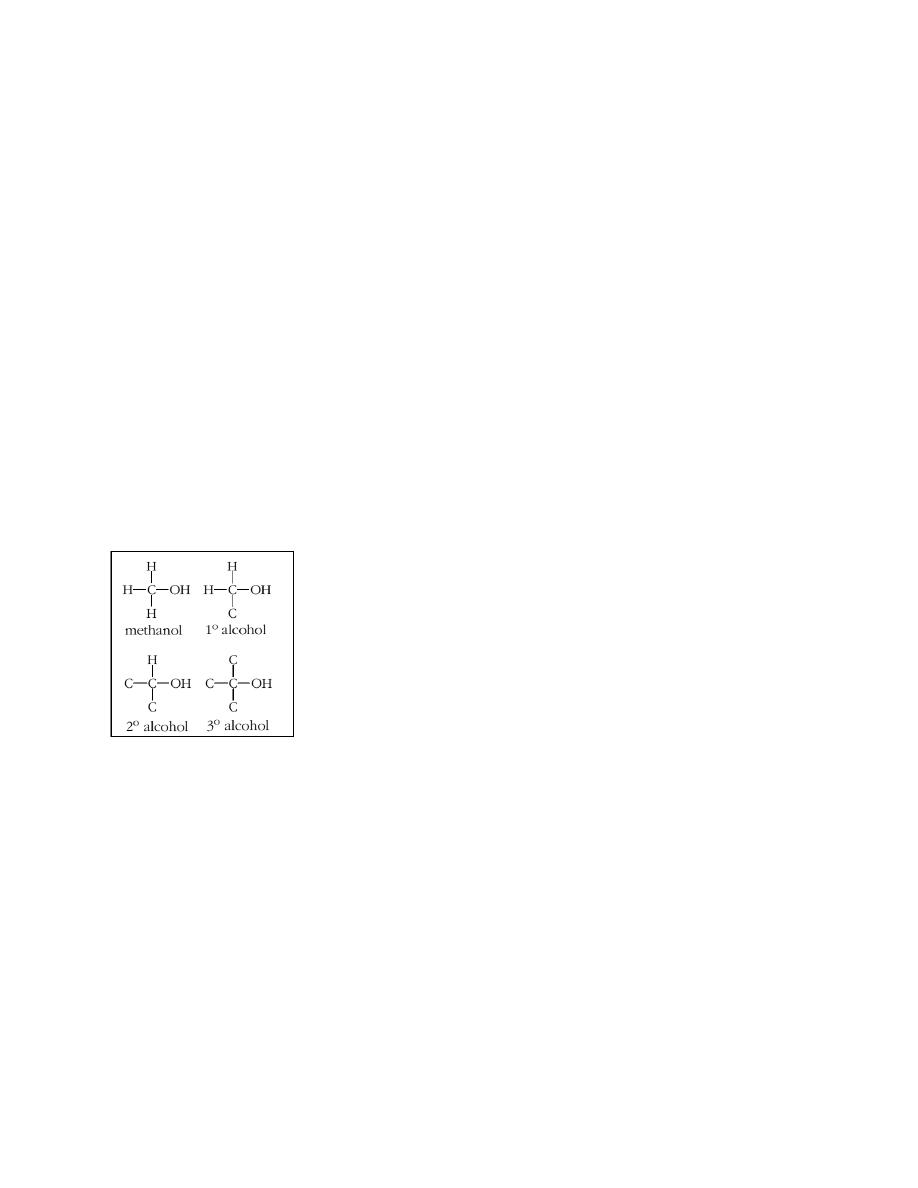

The functional groups we will consider in this experiment are alcohols and phenols.

In alcohols the -OH group is attached to a tetrahedral carbon atom. If the carbon

atom is bonded to three hydrogens in addition to the -OH, the alcohol is methanol.

If the carbon that is bonded to the -OH is bonded to one carbon and two hydrogens,

the alcohol is a primary (1o) alcohol. If the carbon that is bonded to the -OH is

bonded to two carbons and one hydrogen, the alcohol is a secondary (2o) alcohol.

If the carbon that is bonded to the -OH is bonded to three carbons, the alcohol is a

tertiary (3o) alcohol. All of these alcohols share some characteristics but other

characteristics are different owing to their different structures. In phenols the -OH

group is directly attached to a carbon that is part of an aromatic ring. Alcohols and

phenols are similar in some ways, but there are enough differences so that they are

considered different functional groups. One major difference is that phenols are

typically about a million times more acidic than alcohols. Addition of sufficient

aqueous sodium hydroxide to a phenol will cause the -OH group of most of the

molecules present to be deprotonated; this will not happen to an alcohol.

In phenols the -OH group is directly attached to a carbon that is part of an

aromatic ring. Alcohols and phenols are similar in some ways, but there are enough

differences so that they are considered different functional groups. One major

difference is that phenols are typically about a million times more acidic than

alcohols. Addition of sufficient aqueous sodium hydroxide to a phenol will cause

the -OH group of most of the molecules present to be deprotonated; this will not

happen to an alcohol.

Chemical Properties We shall focus on chemical reactions that can help to

distinguish alcohols from phenols and to distinguish among the classes of alcohols.

23

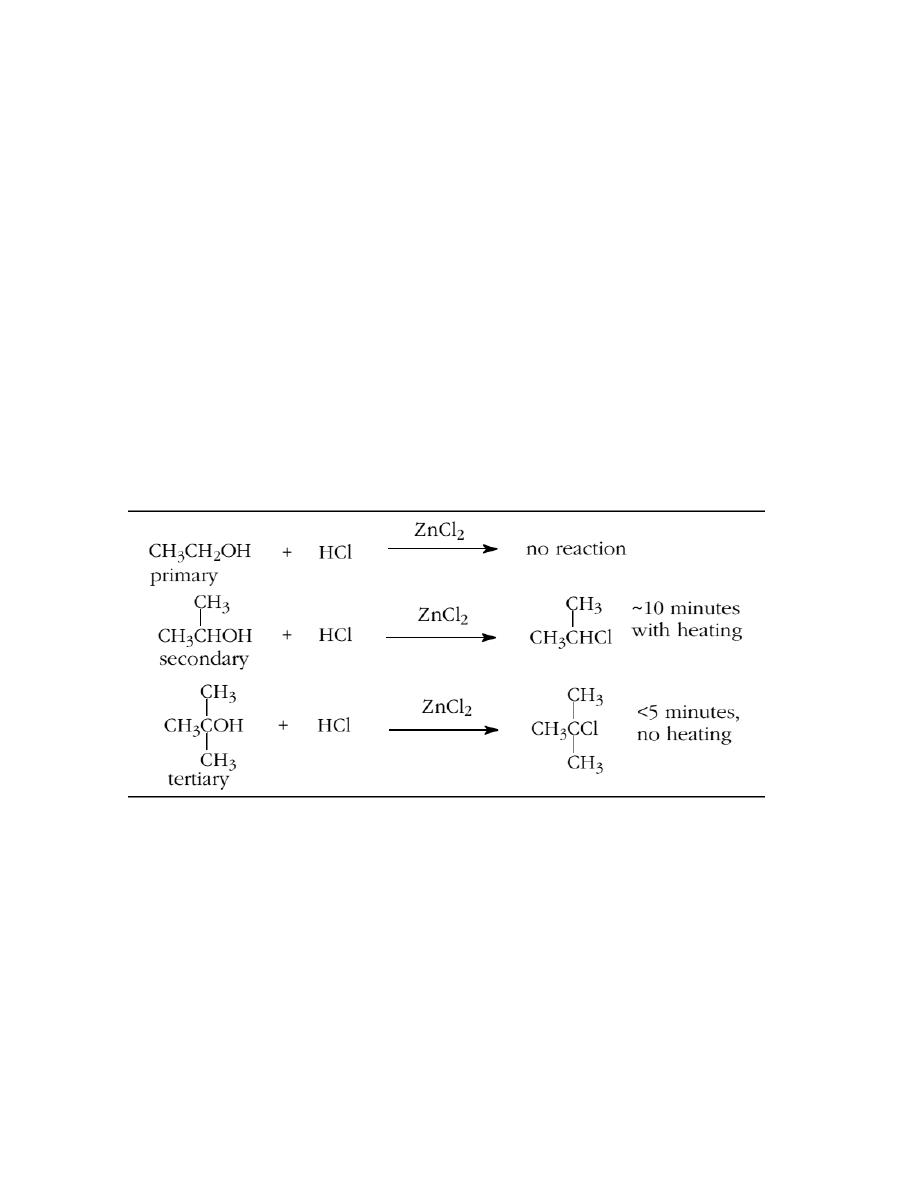

1. Lucas Test.

This test is used to distinguish among primary, secondary, and tertiary water

soluble alcohols. Lucas reagent is a mixture of concentrated hydrochloric acid and

zinc chloride. Zinc chloride is a Lewis acid, which when added to hydrochloric acid

makes it even more acidic. Water soluble tertiary alcohols react with Lucas reagent

almost immediately to form an alkyl chloride which is insoluble in the aqueous

solution. The formation of a second liquid phase in the test tube almost as soon as

the alcohol initially dissolves is indicative of a tertiary alcohol. A secondary

alcohol reacts slowly to form a chloride and, after heating a little, gives a second

phase, usually within 10 minutes. Primary alcohols and methanol do not react

under these conditions. In the case of tertiary alcohols the chloride is usually

attached to the carbon that held the hydroxyl group. In the case of

secondary alcohols, it is often the case that the chlorine is attached to the carbon

that held the hydroxyl, but rearrangements are possible.

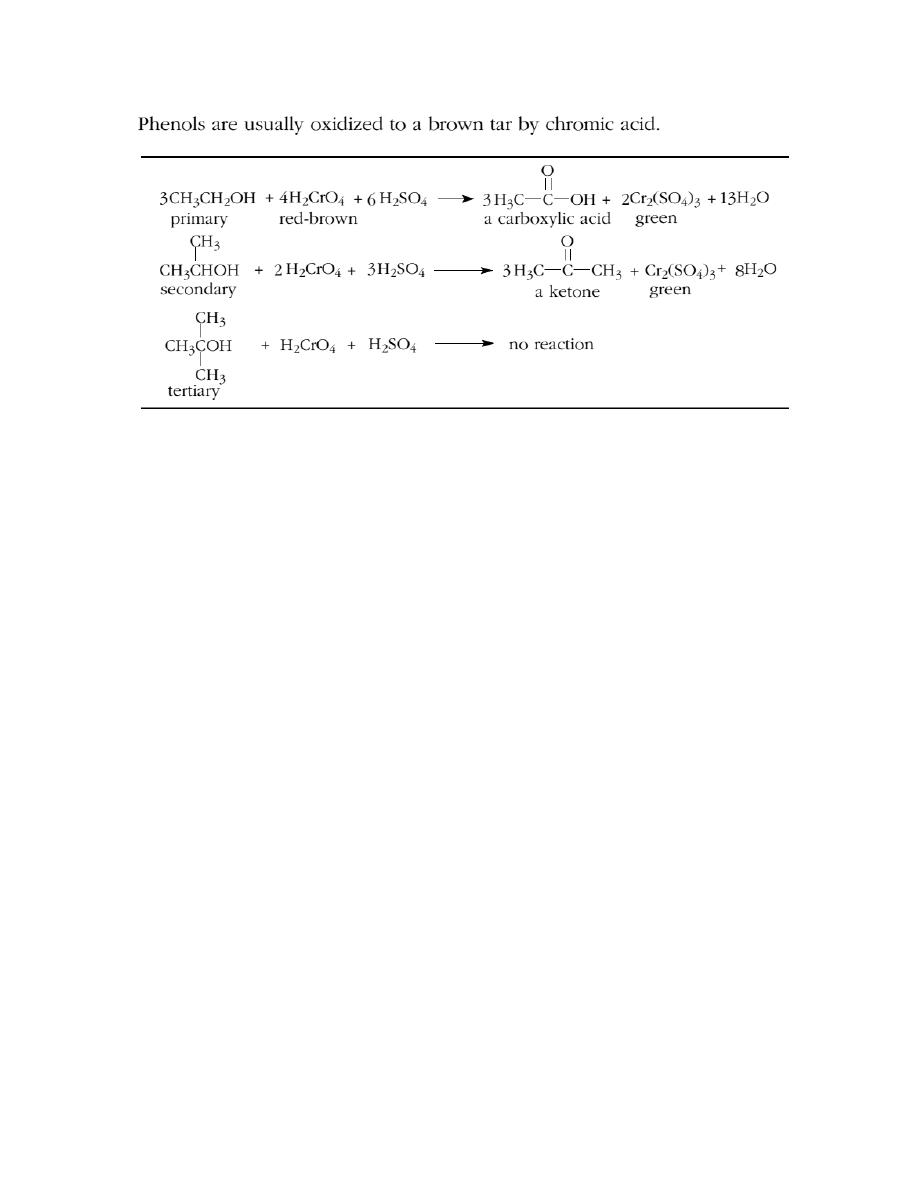

2. Chromic Acid Test. Primary alcohols are oxidized to carboxylic acids by

chromic acid. The Cr+6 in the chromic acid, which is red-brown, is reduced to

Cr+3, which is green. Secondary alcohols are oxidized to ketones by chromic acid.

The chromium reduction is the same here as for the primary alcohols. Tertiary

alcohols are not oxidized by chromic acid. Thus this reaction can distinguish

between primary and secondary alcohols, on the one hand, and tertiary alcohols, on

the other.

24

Acidity of Phenols.

Most phenols are weaker acids than carboxylic acids and stronger acids than

alcohols. When phenols react with a base the phenol is converted into a phenoxide

anion (see reactions below). The phenoxide anion is more soluble in water than the

corresponding phenol. Consequently, if a water-insoluble phenol is treated with an

aqueous solution of a base that is strong enough to convert most of the phenol to

the phenoxide anion, that phenol will dissolve in the aqueous base (as the

phenoxide salt). Aqueous sodium hydroxide and sodium carbonate are strong

enough bases to dissolve most water-insoluble phenols, while aqueous sodium

bicarbonate is not. None of the above-mentioned bases is strong enough to convert

a substantial amount of a typical alcohol into an alkoxide anion (which would cause

a water-insoluble alcohol to dissolve as its alkoxide anion).

25

The order of basicity of the bases appearing on the left in the above equations is,

from most basic to least basic: sodium hydroxide, NaOH > sodium carbonate,

Na

2

CO

3

>sodium bicarbonate, NaHCO

3

.

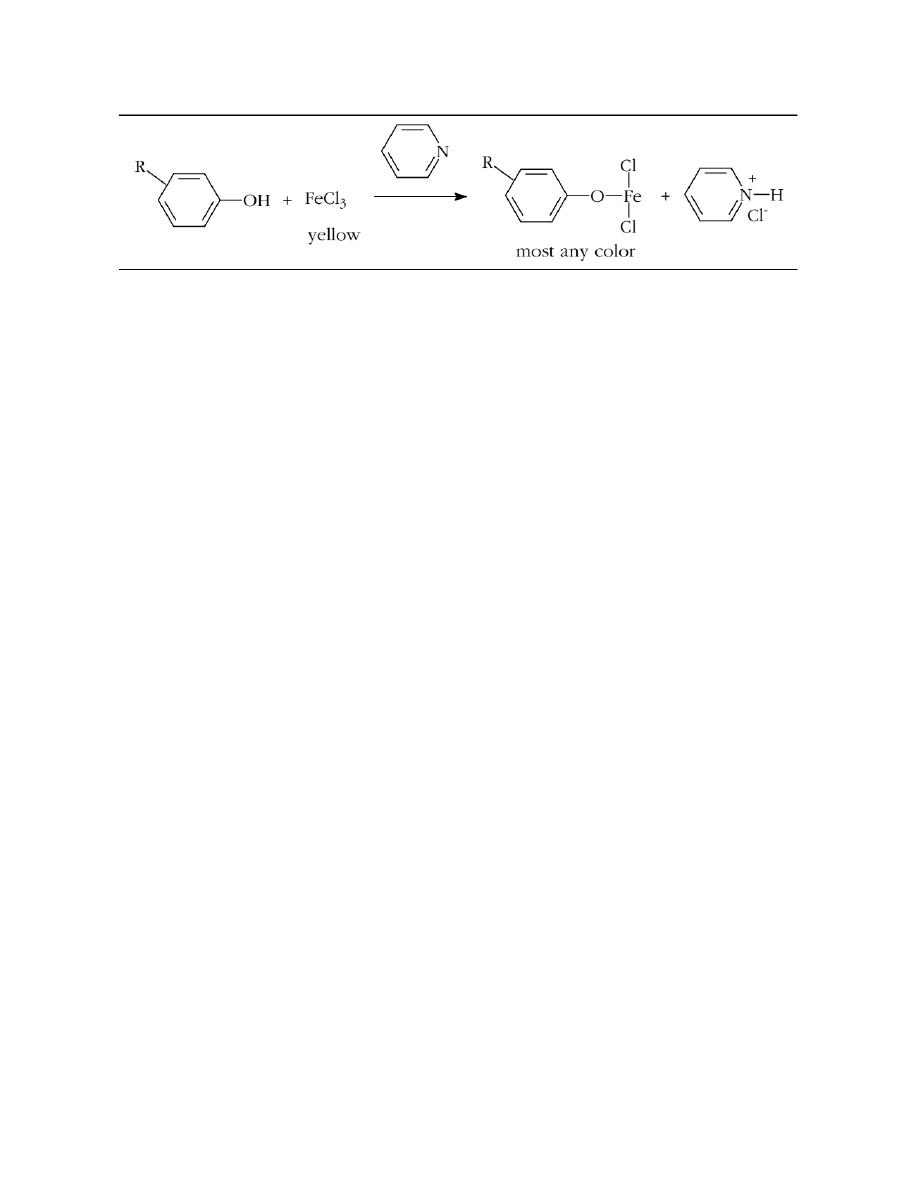

Iron(III) Chloride Test.

Addition of iron(III) chloride dissolved in chloroform (trichloromethane) to a

phenol dissolved in chloroform, gives a colored solution upon addition of pyridine.

Depending on the structure of the phenol the color of the product can be most

anything from red to violet. Alcohols do not give this test.

26

Objectives of the Experiment –

1. To learn something about the physical and chemical properties of alcohols.

2. To use the information obtained about chemical properties to identify an

unknown as a primary, secondary, or tertiary alcohol or phenol.

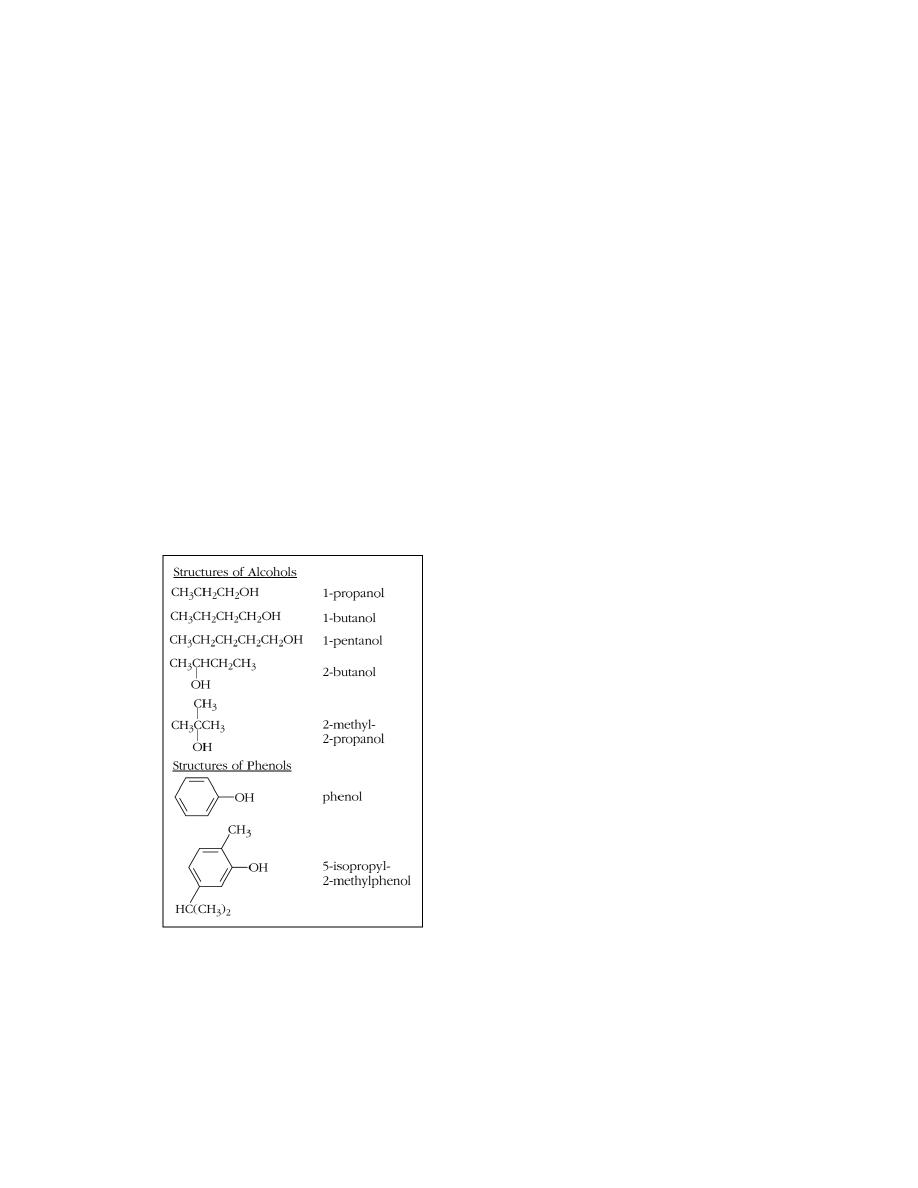

2. Procedure – Solubility of Alcohols and Phenols In each of the following

cases you will attempt to make an approximately 10% (by weight) solution

of the alcohol or phenol in water (very polar) and in hexane (nonpolar) to

see if the compound is soluble to at least that extent.

1. Label clean dry test tubes as follows: 1-propanol, 1-butanol, 1-pentanol, phenol,

5-isopropyl-2-methylphenol. Place 10 drops (= ~0.5 ml = ~0.5 g) of the appropriate

compound into each test tube. In the case of phenol add 0.5 g. Using a 10 ml

graduated cylinder, add 4.5 ml (= 4.5 g) of deionized water to each tube. Agitate

the tubes to mix the contents. (Note that, in general, liquids that are miscible will

dissolve in each other quickly. Solids that are soluble may take some time and

require encouragement like stirring with a stirring rod.) Record on the report sheet

whether the compound is completely soluble, partially soluble, or insoluble in the

water. Discard the contents of the tubes into the sink and wash down the drain with

water. Rinse the test tubes with water, then with a small portion of acetone, then

with a small portion of hexane. Invert the tubes in a beaker and allow them to dry

for a couple of minutes. Rinse the graduated cylinder with acetone and then hexane.

2. Again place 10 drops (in the case of phenol 0.5 g) of each compound into the

corresponding test tube. Using the 10 ml graduated cylinder, add 6.8 ml of hexane

(~4.5 g) to each tube. Agitate the tubes to mix the contents. Note on the report sheet

whether the compound is completely soluble, partially soluble, or insoluble in the

hexane.

Discard the contents of the tubes into the sink and wash down the drain with water.

Rinse the test tubes with water, then with a small portion of acetone. Allow to

drain.

27

1. Lucas Test –

Place 5 drops of each sample into the appropriate tube. Add 1 ml of Lucas

reagent. Stopper the test tube with a cork and agitate the contents of the tube

vigorously by holding the top of the tube with the thumb and index finger of

one

hand

and

striking

the

bottom

of

the

tube

horizontally with the index finger of the other hand. After the contents are

thoroughly mixed, remove the cork and allow the tube to stand for five

minutes.

Look for any cloudiness or separation of a second layer that has developed in

this

5 minute time span. Record results on the report sheet. Allow the tubes to sit

for another 5 minutes and again observe the ones that had been clear to see if

there is any cloudiness or second layer of liquid. Place any tubes that still

have

one

clear layer into a 60

o

C water bath for 15 minutes. Again look for cloudiness

or a second layer of liquid and record your results on the report sheet.

2. Chromic Acid Test– Place 5 drops of each sample into the appropriate clean

dry test tube. To each test tube add 10 drops of acetone and 2 drops of

chromic acid. Stopper the tube with a cork and agitate. Remove the cork and

28

place the tube in a 60oC water bath for 5 minutes. Note the color of each

solution and any other characteristics. Record your observations.

3. Iron(III) Chloride Test – Place 10 drops of each sample into the

appropriate clean dry test tube. Add 10 drops of trichloromethane

(chloroform) to each tube. Add 5 drops of iron(III) chloride in chloroform to

each tube. Add 2 drops of pyridine to each tube. Agitate the tube. Record

your observations.

3. 4. Acidity – Place 5 drops of each sample into the appropriate clean, but not

necessarily dry, test tube. To each test tube add 5 drops of deionized water.

Use a clean glass stirring rod to stir each sample and then touch the wet tip of

the rod to a piece of pH paper on paper. After 15 seconds compare the color

of the paper with the colored scale that accompanies the test paper. Record

the pH of the mixture on your report sheet. Based on these tests you should

be able to identify your unknown as a primary alcohol, secondary alcohol,

tertiary alcohol, or a phenol.

EXPERIMENTAL FIVE

Properties of Carboxylic Acids and Esters

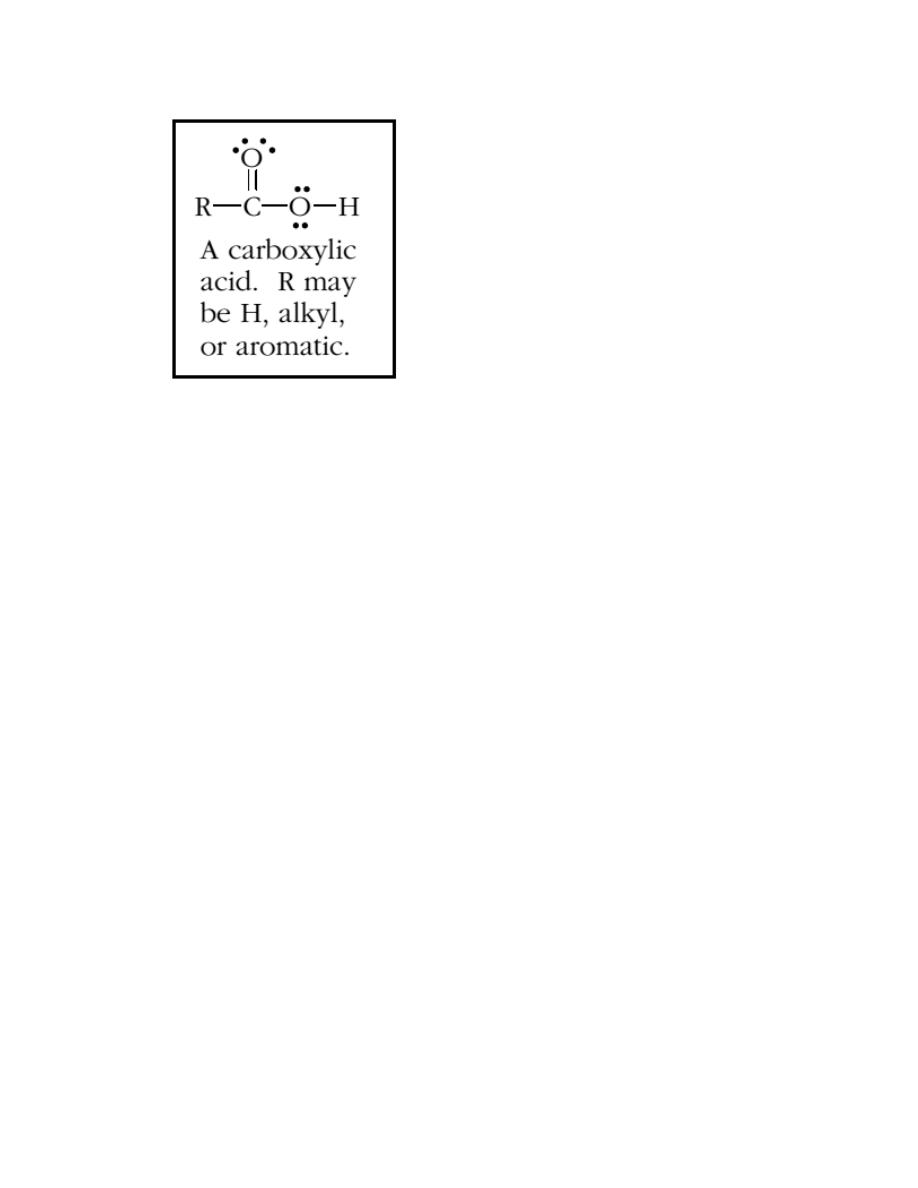

Introduction

Carboxylic acids are characterized by the carboxyl group which combines

the carbonyl group of aldehydes and ketones with the hydroxyl group of

alcohols and phenols. Since the carbonyl and hydroxyl groups are directly

bonded to each other each affects the properties of the other. The result is

that the hydroxyl group of a carboxylic acid is considerably, but not

completely, different from its alcohol or phenol sibling; the same can be said

when one compares the carbonyl of a carboxylic acid with that of an

aldehyde or ketone.

29

When a carboxylic acid is reacted with an alcohol in the presence of a strong

acid, which acts as a catalyst, an ester is formed along with a molecule of

water. An example of this reaction is shown below where acetic acid reacts

with isopentanol (3- methylbutanol) to form the ester isopentyl acetate and

water. Isopentyl acetate is sometimes called banana oil because it is mainly

what gives bananas their fragrance and flavor. This type of reaction is known

as the Fisher esterification, in honor of its discoverer Emil Fisher. It is an

equilibrium reaction and the equilibrium constant is typically about 1. This

means that if one starts with one mole of carboxylic acid and one

mole of alcohol, the result at equilibrium will be one-half mole of ester, one-

half mole of water, one-half mole of carboxylic acid and one-half mole of

alcohol. One way to improve the yield is to remove water from the reaction

mixture as it is formed. This will drive the reaction in the forward direction

and is an example of Le Châtelier’s principle.

[Le Châtelier’s principle: If the conditions of a system, initially at

equilibrium, are changed the equilibrium will shift in such a direction as to

tend to restore the original conditions.] In this case the water is removed and

by Le Châtelier’s principle the substances present will react to form more

water. But by the chemical equation, if more water is formed

more ester will be formed, also. Many esters, like isopentyl acetate, have

pleasant fragrances and are used in perfumes and as flavorings.

Esters can be broken apart under basic conditions, also. This reaction is

called saponification because it can be used to make soap if one selects the

appropriate ester (known as a triglyceride, usually obtained from animal fat)

as starting material. The products of a saponification are an alcohol and the

salt of a carboxylic acid as shown below.

30

Objectives

1. To study some of the physical and chemical properties of carboxylic acids. 2. To

prepare several esters and note their aromas. 3. To saponify two esters. Procedure

Note: You may make the approximation that 20 drops of a liquid equals 1 milliliter.

Characteristics of acetic acid –

1. Place 2 ml of 0.75M acetic acid into a test tube. Note and record the odor.

Dip a glass stirring rod into the solution and touch the wet tip of the stirring

rod to a piece of wide-range pHydrion paper. Compare the color of the paper

with the chart that comes with the paper and record the pH of the solution.

Repeat the above process with 0.75M samples that have been provided of 1-

butanol and phenol. Record odors and pH values as above.

2. Add 2 ml of 1 M aqueous sodium hydroxide to each of the above

solutions. Cork the test tubes and agitate. Remove the corks and determine

the pH of each, as above. If not yet basic (pH > 7) add more sodium

hydroxide by drops, agitating and testing pH as you go. When the solution

becomes basic note any change in the odor and record the result.

3. Now add 2 M aqueous sulfuric acid dropwise to each tube, with agitation,

until the contents of the test tubes are just acidic (test with pHydrion paper,

pH <7; about 20 drops should be required). Note any change in the odors.

Record the results. Clean the test tubes.

2. Characteristics of Benzoic Acid –

3. 1. Weigh 0.10 g of benzoic acid into a test tube. Add 2 ml of water. Agitate

the test tube. Does the benzoic acid have an odor? How soluble is benzoic

acid in water?

4. 2. Add 1 ml of 2 M aqueous sodium hydroxide to the benzoic acid - water

mixture. Stopper the tube with a cork and agitate the test tube in the usual

way by holding the top of the tube with one hand and striking the bottom of

the tube horizontally with the index finger of the other hand. Check with pH

paper to be sure the mixture is basic (pH > 7); if not add more aqueous

sodium hydroxide dropwise until the mixture is basic. Record any

31

observations. 3. Measure and record the pH of the above mixture. Add 20

drops of 3 M hydrochloric acid to the above mixture, dropwise. After every

second drop is added, agitate, check and record the pH, and note any

changes. Saponification

5. Place 20 drops of methyl salicylate and 10 ml of 6 M aqueous sodium

hydroxide into a large test tube labeled “methyl salicylate saponification”.

Record the odor of methyl salicylate. Place 10 drops of cooking oil and 10

ml of 6 M aqueous sodium hydroxide into a large test tube labeled

“triglyceride saponification”. Place the tubes in a steam bath and heat them

for 30 minutes. Every 5 minutes, being careful not to burn yourself with

the steam, remove the tubes from the steam bath and cork and shake them.

After shaking, uncork them and return them to the steam bath. Note: To save

time begin the “esterification” part of the experiment as the test tubes are

steaming. 2. Cool the test tubes to room temperature using an ice-water bath.

3. Record the odor of the material in the methyl salicylate saponification

tube. Then add 6 M hydrochloric acid to this tube, one milliliter at a time,

until the solution is acidic. Stir with a glass rod after each addition and test

with pHydrion paper. Record your observations as the solution becomes

acidic.

4. Cork the tube labeled triglyceride saponification. Shake the tube and

record observations. Then add 6 M hydrochloric acid to this tube, one

milliliter at a time, followed by shaking. After each addition test with

pHydrion paper. Record your observations as the solution becomes acidic.

Fisher Esterification –

1. Label five clean, dry test tubes with numbers corresponding to the compound

pairs listed in the table to the right.

2. Add 10 drops of the corresponding carboxylic acid (0.1 g salicylic) to the

numbered test tubes. Note and record the odor. Then add 10 drops of the

indicated alcohol, recording the odor of the alcohol.

3. Add 5 drops of concentrated sulfuric acid to each test tube, stopper the tubes

with corks and agitate 4. Loosen the corks in the necks of the tubes and

place the tubes in a 60oC water bath for 15 minutes. Remove the tubes

from the bath, allow to cool to room temperature, and add 2 ml of water

to each. Remove a few drops of the top liquid layer from each test tube,

in turn, placing them on a clean watch glass and note the odor. Can you

pair the odors with the following: banana, raspberry, peach, wintergreen,

32

and nail polish remover. [Many nail polish removers are mainly acetone,

but some are based on one of these esters.]

1. Label five clean, dry test tubes with numbers corresponding to the

compound pairs listed in the table to the right.

2. Add 10 drops of the corresponding carboxylic acid (0.1 g salicylic) to

the numbered test tubes. Note and record the odor. Then add 10 drops of

the indicated alcohol, recording the odor of the alcohol. 3. Add 5 drops

of concentrated sulfuric acid to each test tube, stopper the tubes with

corks and agitate.

6. Loosen the corks in the necks of the tubes and place the tubes in a 60oC

water bath for 15 minutes. Remove the tubes from the bath, allow to cool to

room temperature, and add 2 ml of water to each. Remove a few drops of the

top liquid layer from each test tube, in turn, placing them on a clean watch

glass and note the odor. Can you pair the odors with the following: banana,

raspberry, peach, wintergreen, and nail polish remover. [Many nail polish

removers are mainly acetone, but some are based on one of

these esters.]

33

EXPERIMENTAL SIX

AMINES

Organic amines are compounds in which one or more hydrogens of

an ammonia molecule, NH

3

have been replaced by R- or Ar- groups. Amines

may be classified as:

(1) Primary R-NH

2

or ArNH

2

(2) Secondary R

2

NH or ArRNH

2

or Ar

2

NH

(3) Tertiary R

3

N, ArR

2

N, Ar

2

RN

Amines are quite basic. Ammonia itself has a Kb value of 1.8 x 10

-

5

. Aliphatic amines have Kb values of 10

-4

, while aromatic amines have

Kb values as 10

-10

. These differences are explained by the relative stability of

the cation produced in the reaction: G-NH

2

+ H

+

àG-NH

3

+

When G = R,

base strength is increased because the R- group is electron donating group and

therefore stabilizes the cation produced. When G = Ar, the base strength is

decreased because the net effect of the aryl group is to withdraw electrons and

destabilize the cation formed.

The relative base strength of amines can be tested in several ways. Aqueous

solutions of each base can be tested with indicators. Several drops of the amine to

be tested can be added to FeC1

3

solution. If the amine produces sufficient OH

-

to exceed the Ksp for Fe(OH)

3

, a brown gelatinous precipitate

forms. Because iron(III) hydroxide has a very small Ksp value, this test is positive

for very weak bases.

In addition, amines are readily protonated by strong acids such as HCl and

H

2

SO

4

. The water solubility of amines is similar to that of other organic

compounds that contain H-bonding portions. Small aliphatic amines are water

soluble. As the carbon number increases, solubility in water decreases. The

usual limit occurs at about four or five carbons. Thus, methylamine is soluble

in water while aniline is not soluble. Although most amines are NOT water

soluble, amine salts, being ionic, are generally water soluble.

Most pure amines are clear or very pale in color. Often, stock samples

are found to be of various colors, from dark brown to almost black. Amines

are quite easily oxidized to form these highly colored products. However,

most amines can be readily purified by distillation or by recrystallization. This

oxidizability of amines is shown by simple reaction with bleaching powder.

34

Whether an amine is primary, secondary, or tertiary can be determined by the

Hinsberg test. The amine in question is treated with benzenesulfonyl

chloride in KOH and then acidified with HCl. The results are interpreted as

follows:

Amine Type

Benzenesulfonyl

Chloride in KOH

HCl Addition

Primary RNH2

Reacts,

but

product

dissolves

in

OH-

solution

Precipitate forms.

Secondary

Amine

R2NH

Reacts

and

forms

insoluble product

Precipitate remains.

Tertiary Amines R3N

No

reaction.

Amine

remains as second layer

or ppt.

Amine is protonated

and dissolves.

Procedure

I. Solubility of Amines

1. Place 3-mLs of distilled water in a reaction tube. Add ethylamine in 5-drop

increments until a second layer is observed. Record on the data sheet.

2. Repeat the procedure using aniline. Record the results.

3. Repeat the procedure using solid aniline hydrochloride small pea-sized

increments.

II. Basicity of Amines

1. pH paper

a) Place 3-mLs of distilled water in each of three medium sized test tubes. Number

each tube as 1 - 3.

b) Add 5 drops of concentrated NH

3

to Tube 1; 5 drops of ethylamine to Tube 2;

and 5 drops of aniline to Tube 3.

c) Test each solution with pH paper. Record the results on the data sheet.

2. Ferric Chloride Test

Add about 2-mLs of 5% ferric chloride solution to each of the test tubes

from above step 1. Observe and record the results.

35

3. Reaction with Strong Acids

a) Place one drop of concentrated sulfuric acid on a clean dry watchglass. Add 1-2

drops of aniline. Note and record the results.

b) Repeat the procedure using a drop of concentrated HC1. Note and record the

results.

III. Ease of Oxidation

Place about 2.5-mLs of water and one drop of aniline in a reaction tube. Add

a small amount of bleaching powder [Ca(OC1)

2

] about the size of a small

pea. Stopper and shake well. Observe and record.

IV. Derivative Preparation

A. Acetyl (To be prepared in the HOOD!)

(1) Place about 1-mL of acetic anhydride into a medium sized test tube.

Add about 20-25 drops of aniline. Warm gently in the sand bath or in a water

bath on the hot plate for three to four minutes. This should complete the reaction.

(2) Add about 0.5 mL of water, continue to heat. This should hydrolyze any

remaining acetic anhydride. During this time white crystals of the acetamide

should appear.

(3) Add another 0.5-mL of water, heat to boiling. If all product crystals do

not dissolve, add more water as needed. Once the crystals completely

dissolve, remove from the heat. (This is recrystallization.)

(4) Cool thoroughly. Suction filter. Press dry. Obtain and record a melting point

for the product.

B. Benzoyl (To be prepared in the HOOD!)

(1) Place about 20 drops of aniline in a medium-size test tube. Add 5-mLs

of 10% NaOH. Stopper the tube well.

(2) Add about 5 drops of benzoyl chloride. Stopper and shake gently. Benzoyl

chloride is a lachrymator. It should be handled carefully in the hood. It should

NEVER be washed down an open sink. Rapid hydrolysis increases eye irritation.

(3) Add more benzoyl chloride in 5-drop increments. After each

addition, stopper the tube and gently shake it. CAUTIOUSLY smell the

tube after shaking. If no irritating odor is present, add another 5 drops of

36

benzoyl chloride. This technique of addition prevents a large excess of the

benzoyl chloride being present.

(4) Once the addition seems complete and product crystals of the

benzanilide appear, cool the reaction mixture and suction filter using the Hirsch

funnel. Wash the crystals with cold water. (NOTE: if excess benzoyl chloride is

present, the filtration process will be accompanied by irritating fumes.)

(5) Recrystallize the crystals from hot ethyl alcohol.

(6) Cool, suction filter, press dry, and obtain a melting point.

C. Diphenylthiourea

(1) Place about 20 drops of aniline in a medium test tube. Add aboutt. two mLs of

ethyl alcohol.

(2) Add about one-mL of phenylisothiocyanate to the test tube. Stopper

and shake.

(3) Crystals of diphenylthiourea should appear within a few minutes. If no

crystallization is observed, follow the steps outlined below.

(a) Cool thoroughly in an ice-water bath.

(b) Scratch the inside of the test tube with a stirring rod.

(c) Add a little ice-water.

(d) Wait.

(4) Once crystals form, cool thoroughly. Suction filter using the Hirsch funnel.

(5) Recrystallize from a little hot ethyl alcohol.

EXPERIMENTAL SEVEN

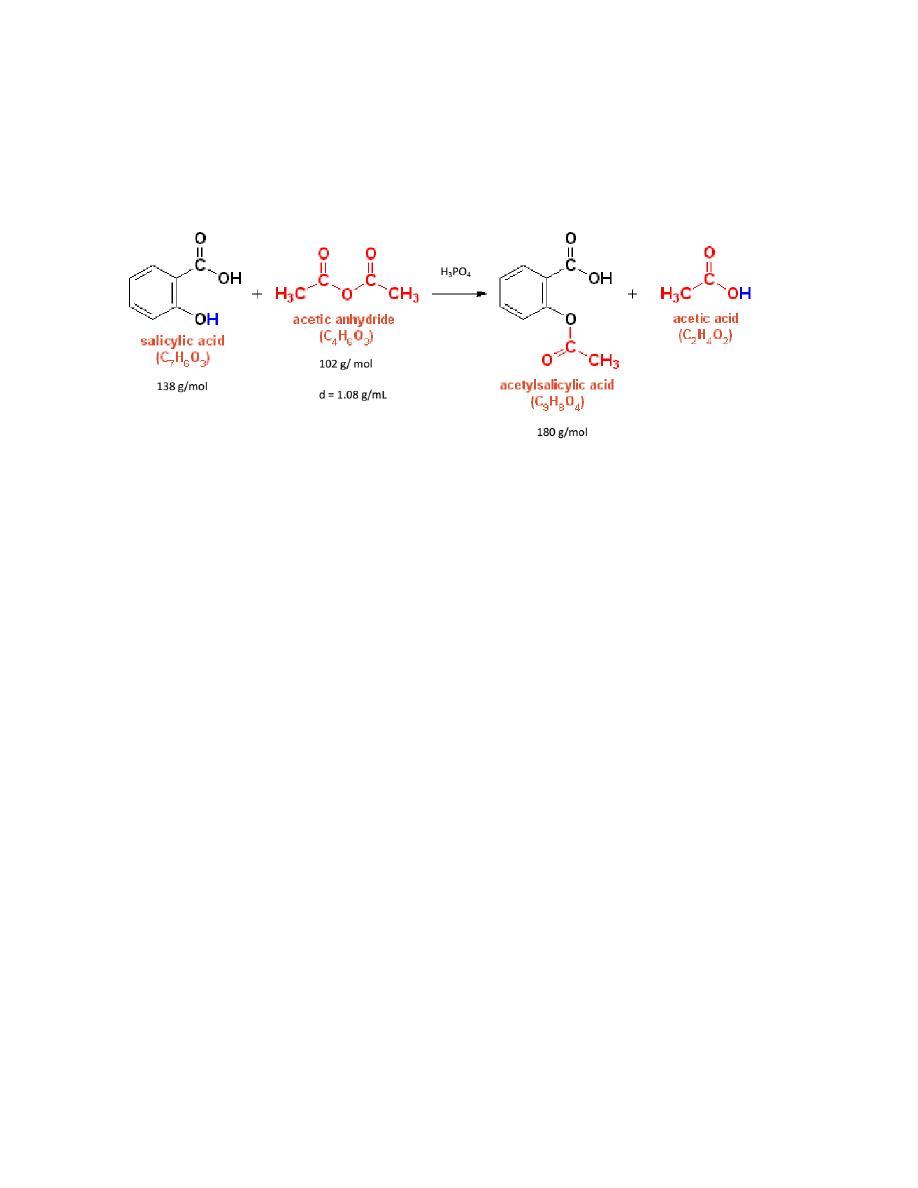

Preparation of aspirin

Aspirin is the common name for the compound acetylsalicylic acid, widely used as

a fever reducer and as a pain killer. Salicylic acid, whose name comes from Salix,

the willow family of plants, was derived from willow bark extracts. In folk

medicine, willow bark teas were used as headache remedies and other tonics.

Nowadays, salicylic acid is administered in the form of aspirin which is less

irritating to the stomach than salicylic acid. To prepare aspirin, salicylic acid is

reacted with an excess of acetic anhydride. A small amount of a strong acid is used

37

as a catalyst which speeds up the reaction. In this experiment, phosphoric acid will

be used as the catalyst. The excess acetic acid will be quenched with the addition of

water. The aspirin product is not very soluble in water so the aspirin product will

precipitate when water is added. The synthesis reaction of aspirin is shown below:

Since acetic acid is very soluble in water, it is easily separated from the aspirin

product. The aspirin isolated in this step is the “crude product”. A “purified

product” can be obtained through recrystallization of the crude product in hot

ethanol. In this experiment, the crude product will be the desired product. The

percent yield of the crude product will be determined for this reaction. The purity

of the product will also be analyzed. The product will be analyzed by three

different methods: melting point, titration, and spectroscopic assay. The melting

point range of pure aspirin is 138-140

C and the melting point range of the

salicylic acid starting material is 158-161

C. If impurities are present in your crude

sample, the melting point range for your product will be lower than the range of

pure aspirin. Also, your melting point range may be greater than 2 degrees.

From the titration of your sample, the moles of acetylsalicylic acid present can be

determined assuming that there is not a large percentage of an acid impurity present

in your crude sample.

The spectroscopic analysis of aspirin will involve the complexing of iron(III) to the

deprotonated form of salicylic acid (salicylate ion) to give a purple solution. Only

the salicylate ion complexes to iron(III). Your aspirin product as well as a

commercial aspirin tablet will be compared to a standard 0.15% ferricsalicylate

solution. In the presence of moisture, aspirin may decompose (hydrolysis) into

salicylic acid and acetic acid. This reaction is the reverse of the synthesis reaction.

The maximum allowable amount of free salicylic acid in an aspirin sample is

0.15% salicylic acid.

38

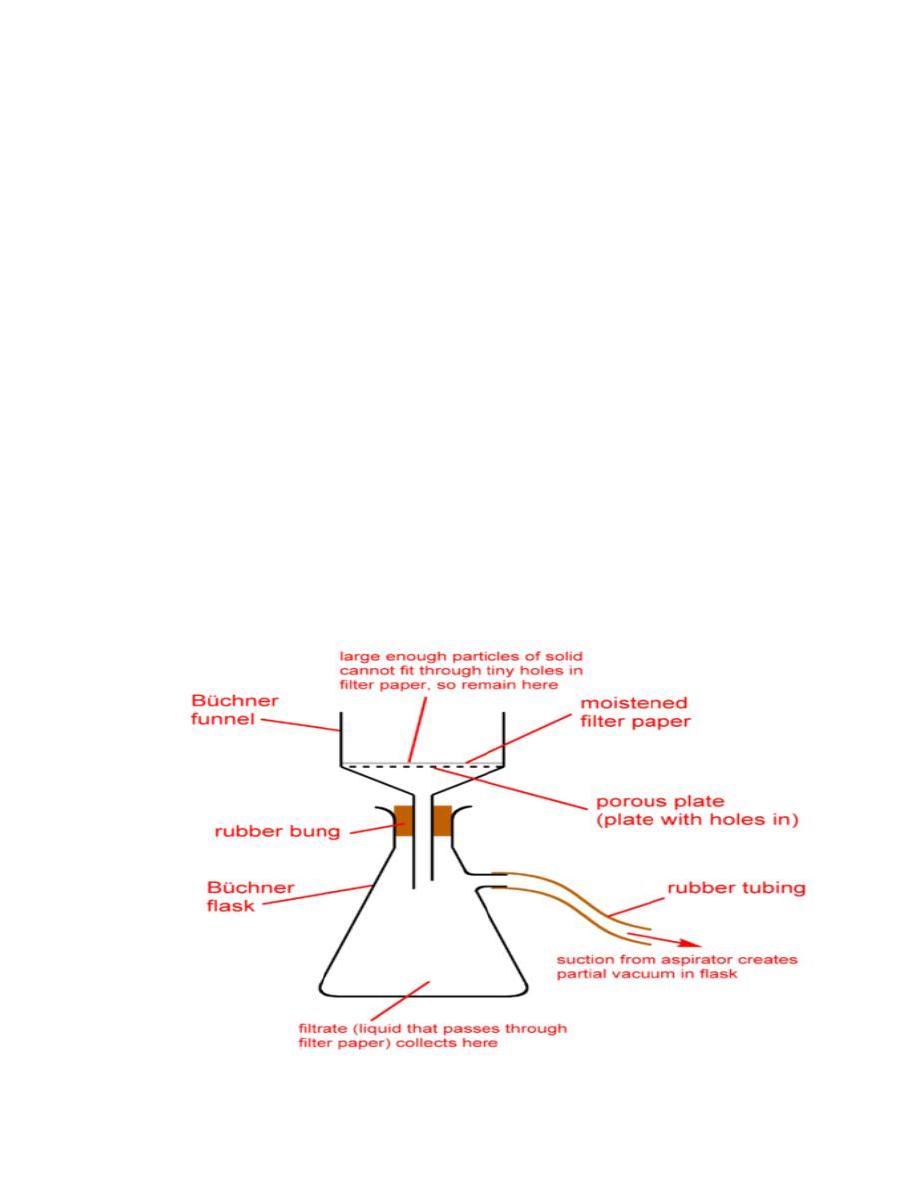

Procedure

1. Use a centigram balance to weigh a 50 mL Erlenmeyer flask. Place about 2 g

of sylicylic acid in the flask and weigh again. In the fume hood, the

instructor will transfer 5.0 mL of acetic anhydride from a buret into the flask.

Add 5 drops of 85% phosphoric acid (catalyst) to the flask.

2. 2. Clamp the flask in a beaker of tap water supported on a ring stand over a

burner flame. Stir if needed to dissolve the salicylic acid. Heat the water to

boiling, and shut off the flame. Keep the flask in the hot water bath for 10

more minutes.. While the flask is still in the water bath, slowly add 2 mL of

distilled water to the flask to decompose any excess acetic anhydride.

3. After a minute, remove the flask from the water bath and add 20 mL of

distilled water. Let theflask cool to room temperature. As the solution cools,

crystals of aspirin will appear. Cool the solution further by placing the

reaction flask in an ice bath. Chill 5-10 mL of distilled water in a separate

container.

4. Weigh a watch glass and filter paper on the centigram balance.

5. Set up a Büchner funnel on a vacuum flask connected to a water aspirator.

Place the filter paper in the funnel and moisten with distilled water from a

squirt bottle. Turn on the aspirator and transfer the aspirin slurry into the

funnel. Wash the crystals with 5 mL of the cold DI water.

39

6. Transfer the filter paper and aspirin to a pre-weighed watch glass and

allow to air dry in your locker until the next lab period.

7. It is safe to discard of the filtrate down the sink with water. ay 2 –

Analysis/Melting

Point

1. Weigh the dry product to obtain the yield of the reaction. Calculate the

theoretical yield and percent yield of the reaction. 2. Pack a few crystals of

your aspirin product in a melting point capillary tube. Your instructor will

demonstrate how to use the melting point apparatus. Allow the temperature

of the melting point apparatus to increase 1

C per minute starting from 120

C. Measure the melting point range of the aspirin product. The melting

point range is the temperature when you first notice the aspirin crystals

melting up until the temperature when no crystals remain.

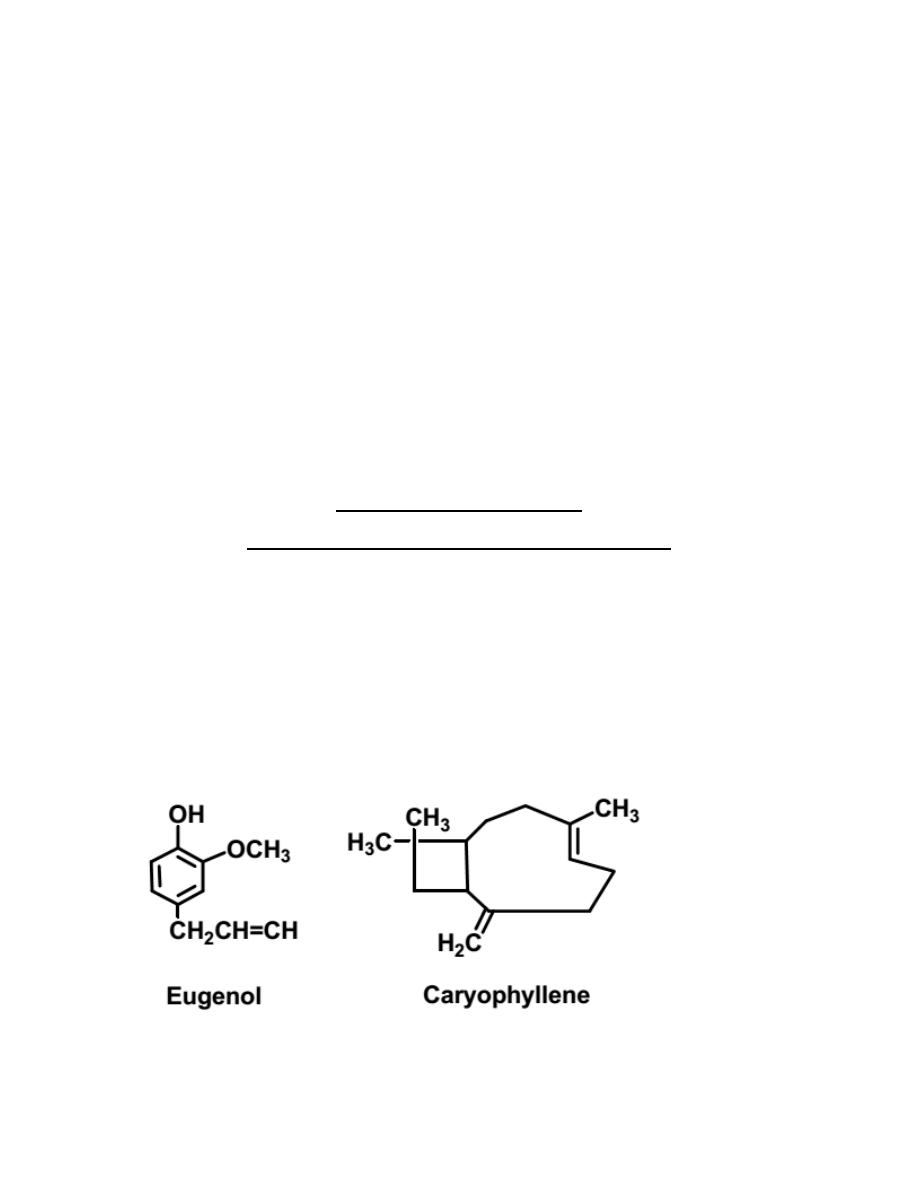

EXPERIMENTAL EIGHT

EXTRACTION of Eugenol oil from clove plant

An essential oil is a substance extracted from a plant material. It is a hydrophobic

liquid containing highly volatile aromatic compounds. Essential oils are generally

extracted by distillation. The essential oils which impart the distinctive aromas are

complex mixtures of organic constituents, some of which being less stable, may

undergo chemical alterations when subjected to high temperatures. In this case,

organic solvent extraction is required to ensure no decomposition or changes have

occurred which would alter the aroma and fragrance of the end-product.

Oil of clove is rich in Eugenol (4-allyl-2-methoxyphenol). Caryophyllene is also

present in relatively small amount, along with other terpenes. Clove oil is made

40

from the buds of the flower of a tree that grows in tropical equatorial regions. It is

intense oil, most commonly used to relieve dental pain and infection and to

dissolve the eggs deposited by intestinal worms. Clove oil is delicious but

overwhelming in both smell and taste. It is antiseptic, carminative, warm and very

aromatic. It is often used as a flavoring in toothpaste, mouthwashes, and exotic

foods. In this experiment, the essential oil of clove will be isolated by distillation

and extracted with dichloromethane.

1- Crush 1.5 g of dry cloves into very small pieces. Place them in 25-mL round

bottom flask. Add 15 mL of water and swirl well.

2. Connect the flask with a receiver distilling still and a water-cooled condenser.

Distil the solution to obtain the distillate in the trough of the still about 7 mL.

3. Transfer the distillate with a Pasteur pipette into the 10-mL conical bottom flask,

Flask No.1. Rinse the still with 2 mL of dichloromethane and transfer the

dichloromethane into Flask No.1. Stir the mixture using a Pasteur pipette

method.

(Draw a portion of the lower layer up into a pipette and carefully expel it back

into the flask, through the upper layer. Do this repeatedly for a few times).

: If the dichloromethane is not mixed well, the incomplete separation and the

poor yield will be obtained.

4. Allow the mixture to separate completely into two distinct layers. Remove the

lower dichloromethane layer, using a Pasteur pipette method (Squeeze the

rubber bulb and lower the tip of the pipette to the bottom of the flask. Carefully

draw up the lower layer until the interface between the layers reaches the

pipette tip. Lift out the pipette and expel any drops of the upper layer caught in

the tip. Then transfer the lower layer in the pipette into another container).

Transfer it into another conical bottom flask, Flask No.2.

5. Repeat extraction of the liquid in Flask No.1 with another 2 mL of

dichloromethane as described in steps 3-4. Combine the dichloromethane in

Flask No.2.

6. Add a small amount of anh.Na2SO4 and swirl the solution. Keep adding until

someof it swirls freely, and then set aside when the solution is no longer

cloudy.

7. Filter the solution using a Pasteur filter-tip pipette method. (Wrap the Pasteur

pipette tip with a small piece of cotton wool. Immerse the pipette into the

solution until the pipette tip reaches the bottom of the flask while squeezing

the rubber bulb. Draw the solution up into the pipette by releasing the

41

rubber bulb. Take off the cotton wool and expel the solution in the pipette

into the proper container).: Be careful not to lose the cotton wool during

suction. While lifting the pipette out, apply a little pressure by squeezing

the bulb softly to prevent suction of unfiltered solution into the pipette..

Transfer the solution in the pipette into another conical bottom flask, Flask

No.3. Connect the flask with a receiver distilling still and a water-cooled

condenser. Distil off dichloromethane to obtain the product at the bottom of

the flask.

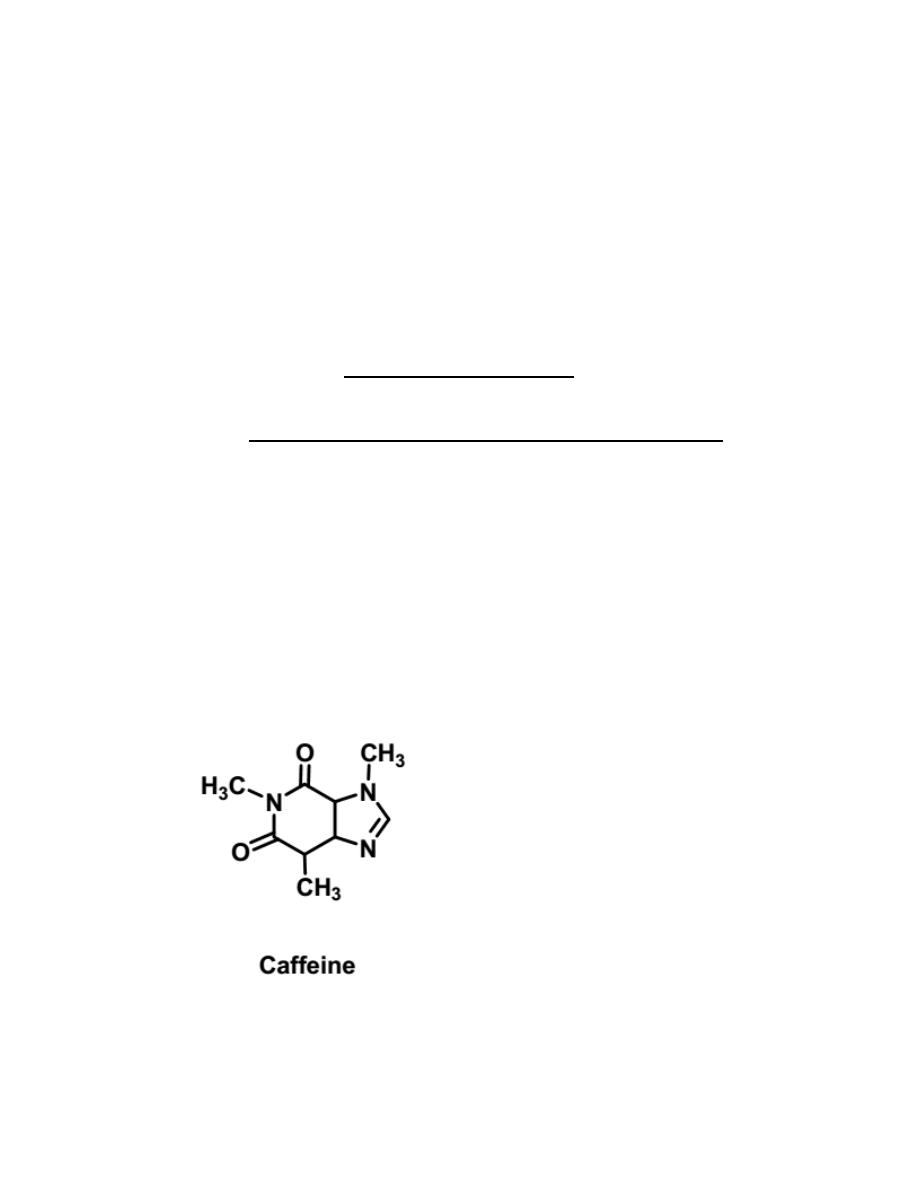

EXPERIMENTAL NINE

ISOLATION OF CAFFEINE FROM TEA LEAVES

Caffeine is an alkaloid which is a class of naturally occurring compounds

containing nitrogen and having the properties of an organic amine base.

Caffeine is the most powerful xanthine in its ability to increase alertness, put

off sleep and to increase one’s capacity for thinking. Caffeine is a vasodilator

(relaxes the blood vessels) as well as a diuretic (increases urination).

Caffeine does not exist alone in tea leaves. The leaves are mainly

cellulose, pigments and chlorophylls, and tannins. Tannins are phenolic

compounds of high molecular weight that have certain properties in

common. Caffeine is found in varying quantities in many plants. Some of the

better-known plant sources are coffee and cocoa beans, tea leaves, and kola

nuts.

In this experiment, caffeine will be extracted from tea and purify it by

sublimation.

42

Extraction of caffeine

1. Weigh 2 tea bags in 50-mL beaker and record their mass.

2. Place 15 mL of water, 2 g of Na2CO3, and a boiling stone into a 25-mL

round bottom flask. Boil the solution gently in a heat dissipation block on a

hot plate.

3. Pour a hot solution (from step 2) in a beaker containing 2 tea bags.

Completely immerse 2 tea bags into the solution and let them soak for 3

minutes.

: Occasional press the tea bags using a stirring rod. Be careful not to tear the

bag

open.

4. Transfer 10 mL of the solution into 10-mL conical bottom flask, Flask No.1.

Add a boiling stone. Connect the flask with a receiver distilling still fitted with a

water cooled condenser. Distil off water as much as possible

.5. Pour the rest of the solution into Flask No.1 and continue distillation until 2-3

mL of the solution is left in the flask.

6.

Allow

the

solution

to

cool

down

at

room

temperature.

7. Add 3 mL of dichloromethane and gently stir the mixture using a Pasteur pipette

method. (Draw a portion of the lower layer up into a pipette and carefully expel it

back into the flask, through the upper layer. Do this repeatedly for a few times). :

Gently mix the mixture. If not it may cause the emulsion occur in the mixture.

8. Allow the mixture to separate completely into two distinct layers. Remove the

lower dichloromethane layer, using a Pasteur pipette method. (Squeeze the rubber

bulb and lower the tip of the pipette to the bottom of the flask. Carefully draw up

the lower layer until the interface between the layers reaches the pipette tip. Lift

out the Pasteur pipette from the solution while still squeezing the rubber bulb and

expel any drops of the upper layer caught in the tip. Then transfer the lower layer

in the pipette into another container). Transfer it into another conical bottom flask,

Flask No.2.

: Be careful not to lose the cotton wool during suction. While lifting the pipette

out, apply a little pressure by squeezing the bulb softly to prevent suction of

unfiltered solution into the pipette.

43

9. Repeat the extraction of the solution in Flask No.1 with another 3 mL of

dichloromethane as described in steps 7-8. Combine dichloromethane in Flask

No.2.

10. Wash the dichloromethane layer in Flask No.2 with 2 mL of 5% NaOH and

then 2 mL of water using a Pasteur pipette method as described in steps 7-8.

Transfer dichloromethane in the pipette into another conical bottom flask, Flask

No.3. : Discard the upper aqueous layer.

11. Add a minute amount of anh.Na2SO4 and swirl the solution. Keep adding until

some of it swirls freely, and then set aside the solution is no longer cloudy.

12. Filter the solution using a Pasteur filter-tip pipette method. (Wrap the Pasteur

pipette tip with a small piece of cotton wool. Immerse the pipette into the solution

until the pipette tip reaches the bottom of the flask while squeezing the rubber

bulb. Draw the solution up into the pipette by releasing the rubber bulb. Lift out the

Pasteur pipette from the solution while still squeezing the rubber bulb. Take off the

cotton wool and expel the solution in the pipette into the proper container). : Be

careful not to lose the cotton wool during suction. While lifting the pipette out,

apply a little pressure by squeezing the bulb softly to prevent suction of unfiltered

solution into the pipette.

13. Transfer the solution in the pipette into another conical bottom flask, Flask

No.4. Connect the flask with a receiver distilling still fitted with the water-cooled

condenser. Distil off the dichloromethane to obtain the solid at the bottom of the

flask.

Another method

Isolation of Caffeine from Tea.—Boil gently 10 grams of tea with 500 cc. of water

for 15 minutes. Filter through a folded filter, and precipitate the tannin by adding)

drop by drop, to the hot filtrate a 10 per cent solution of lead acetate. When a

precipitate is no longer formed, filter the solution again, and evaporate it to about

75 cc. If a precipitate has separated during the evaporation, filter again. Cool the

solution,

and

extract

it

with

30

cc.

of

chloroform.

Separate

the chloroform and filter it through a dry paper. Set the solution aside to evaporate

pontaneously. Observe the appearance of the crystals. Apply the murexide test to a

few of the crystals. Use in one experiment nitric acid, and in another bromine-

44

water. (See experiment 161d above.) Sublime the rest in watch-glasses. (See §35,

page 24.) Taste a little of the sublimed caffeine.

Sublimation of product

Transfer the solid into a suction flask equipped with a cold finger. Sublime the

solid by heating in a heat dissipation block on a hot plate. When sublimation is

complete, carefully lift out the cold finger. Scrape off the crystals, weigh and

calculate its percent recovery. Determine its melting point.

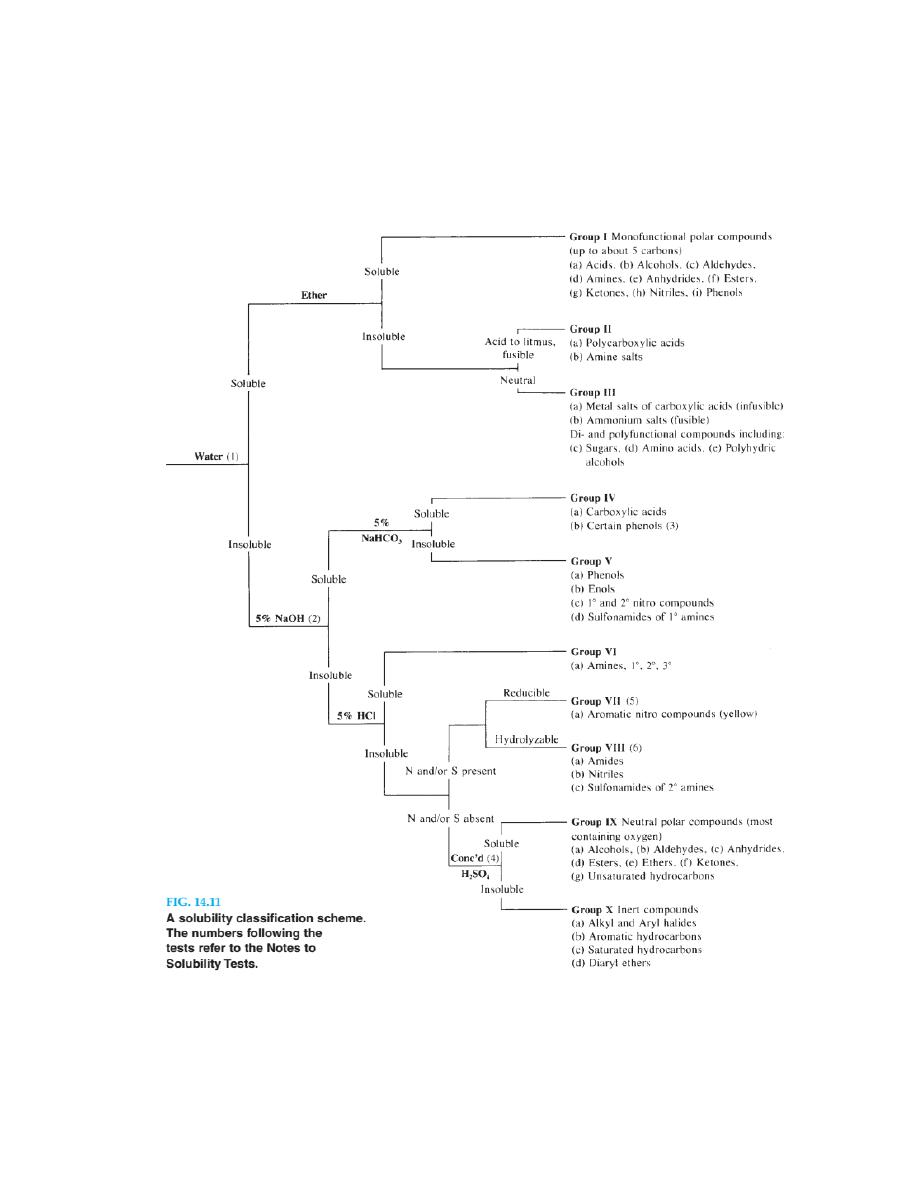

Notes to Solubility Tests

1. Groups I, II, III (soluble in water). Test the solution with pH paper. If the com

pound is not easily soluble in cold water, treat it as water insoluble but test

with

indicator

paper.

2. If the substance is insoluble in water but dissolves partially in 5% sodium

hydroxide, add more water; the sodium salts of some phenols are less soluble

in alkali than in water. If the unknown is colored, be careful to distinguish

between the dissolving and the reacting of the sample. Some quinones (colored)

react with alkali and give highly colored solutions. Some phenols (colorless)

dissolve and then become oxidized to give colored solutions. Some compounds

(e.g., benzamide) are hydrolyzed with such ease that careful observation is

required to distinguish them from acidic substances.

3. Nitrophenols (yellow), aldehydophenols, and polyhalophenols are sufficiently

strongly acidic to react with sodium bicarbonate.

4. Oxygen- and nitrogen-containing compounds form oxonium and ammonium

ions in concentrated sulfuric acid and dissolve.

5. On reduction in the presence of hydrochloric acid, nitro compounds form

water-soluble amine hydrochlorides. Dissolve 250 mg of tin(II) chloride in

0.5 mL of concentrated hydrochloric acid, add 50 mg of the unknown, and

warm. The material should dissolve with the disappearance of the color and

give a clear solution when diluted with water.

6. Most amides can be hydrolyzed by short boiling with a 10% sodium hydroxide

solution; the acid dissolves with evolution of ammonia. Reflux 100 mg of the

sample and a 10% sodium hydroxide solution for 15–20 minutes. Test for the

evolution of ammonia, which confirms the elementary analysis for nitrogen

and establishe s the presence of a nitrile or amide.

45

46

Part Two

Biochemistry

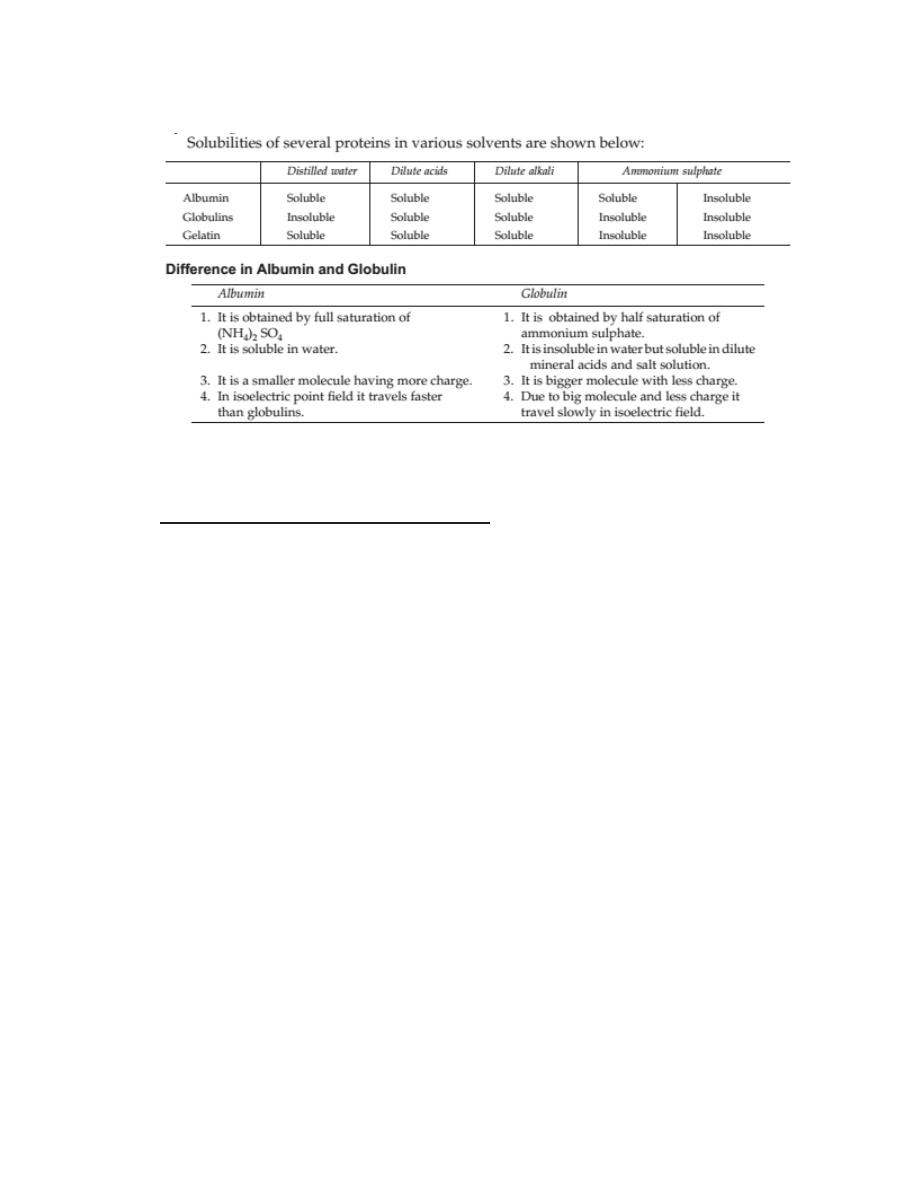

Over the years, the world of Biochemistry has seen many changes for better

investigational techniques for the welfare of the patients. Hence it becomes

mandatory for any written material to show the changes duly. In this section, my

efforts have gone in a direction to improve the material.

In the ever expanding knowledge of Biochemistry it is very difficult on the part of

single individual to go through the various bigger volume of textbooks on practice

of biochemical investigations. This section in a concise but equally satisfactory

form will help the students and practitioners either to a great extent. Besides being

handy it has been kept up to its spirit of recent approaches by virtue of which one

has the best utility in a busy time. For every medical practitioner and enlighten

patients, Biochemistry has been playing a significant role. This section will

certainly be of significant importance to the practitioners as well as laboratories.

Methods of Expressing Concentration Concentration may be defined as weight per

unit volume.The most common expressions are:

1.Percent

2.Molarity

3.Normality

4.Molality

5.Formality.

1.Percent

According to Caraway there are three ways of expressing percentage of solution,

i.e. W/W, W/V,V/V. a. Weight per unit weight (W/W) A 10% W/W solution

contains 10 gm of solute in 90 gm of solvent. b. Weight per unit volume (W/V) A

10% W/V solution contains 10 gm of solute dissolved in final volume of 100 ml of

solution c. A 10% V/V solution contains 10 ml of the concentrate per 100 ml of

solution.

47

Physical Chemistry

pH Determination All biochemical reactions are greatly influenced by the

hydrogen ion concentration of the surrounding medium in which the reaction takes

place. The most convenient way of expressing hydrogen ion concentration is by the

term pH. pH is defined as the negative logarithm of the hydrogen ion concentration

of the solution. Hence it is both important and useful to know some of the simple

methods of pH determination. pH can be determined both by colorimetric and

electrometric methods. Electrometric method is the most accurate one and is done

by using a pH meter whereas colorimetric determination of pH can be simply done

by the following methods:

1.

Indicator

papers

also

called

narrow

range

pH

papers.

2. Universal indicators.

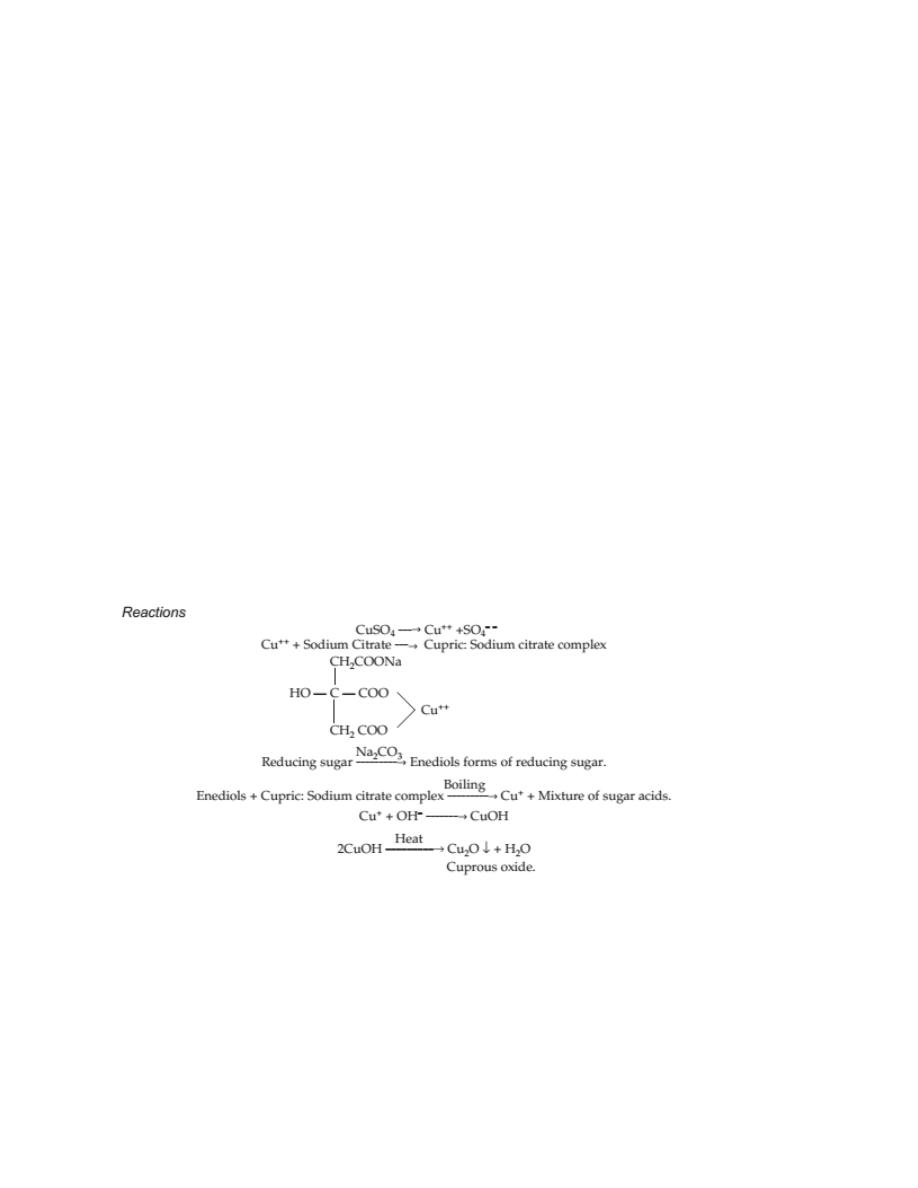

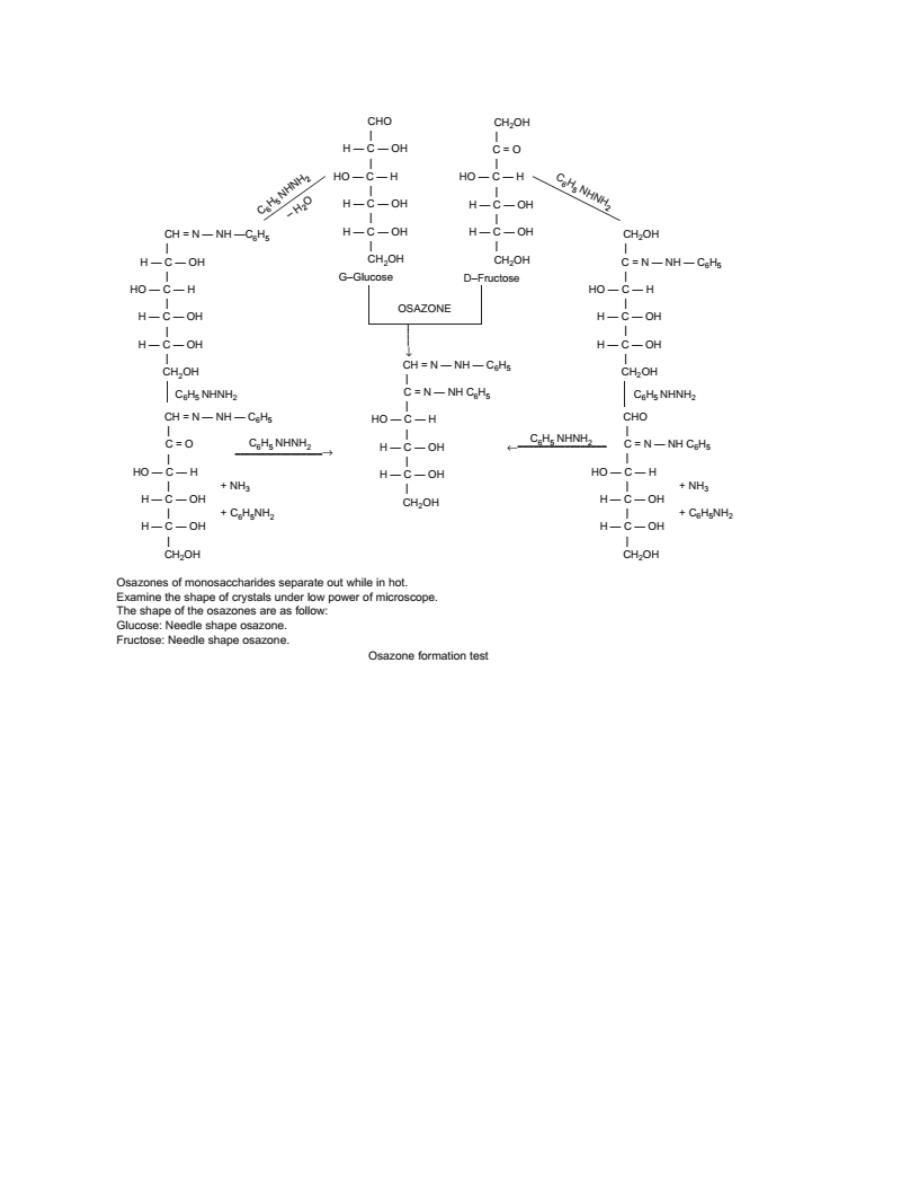

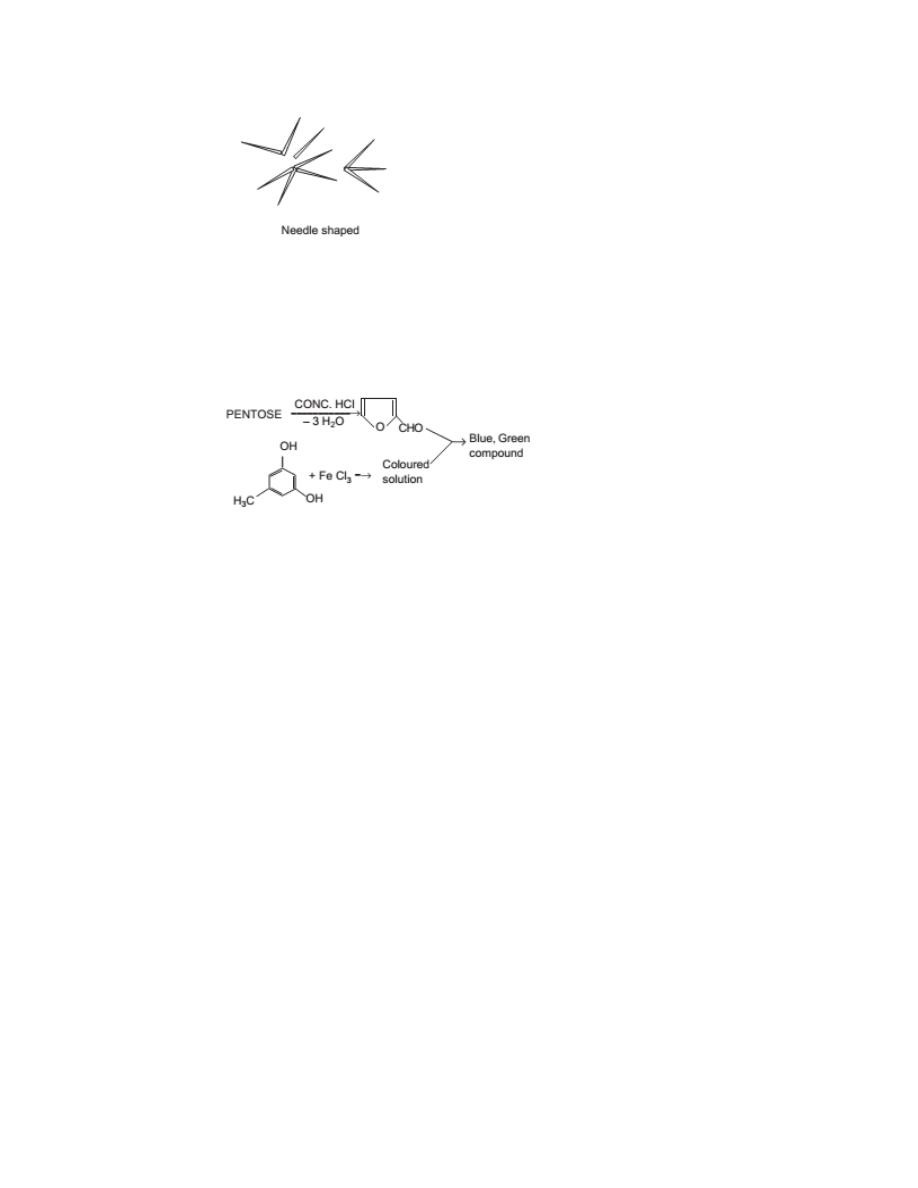

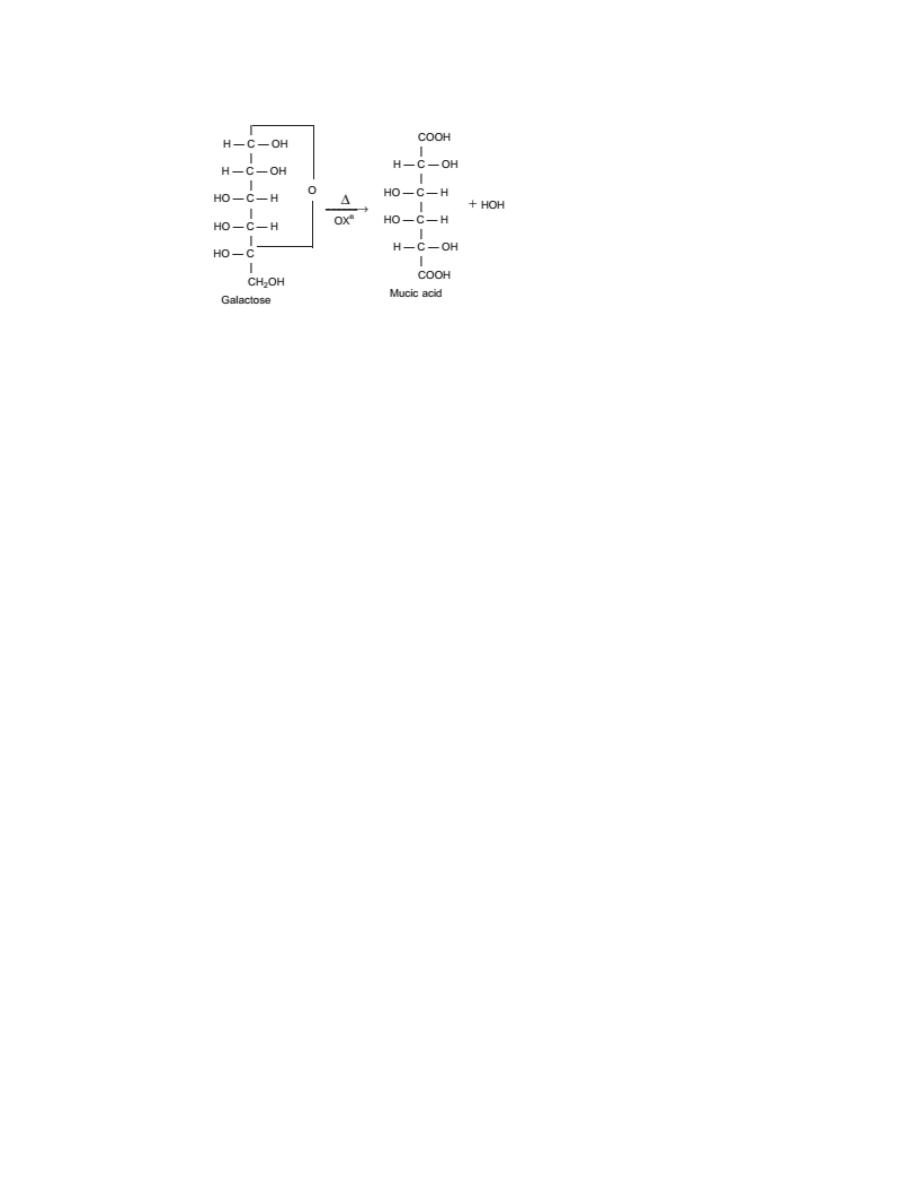

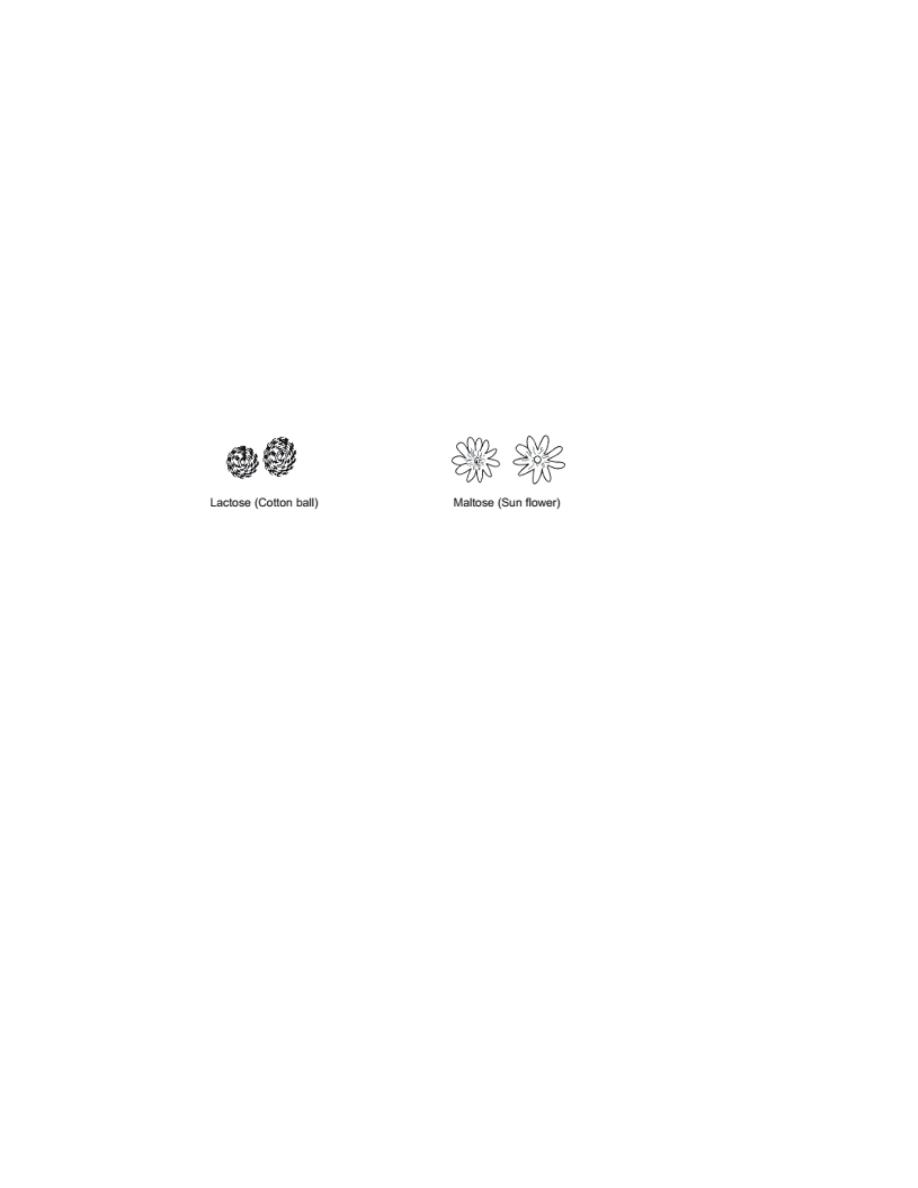

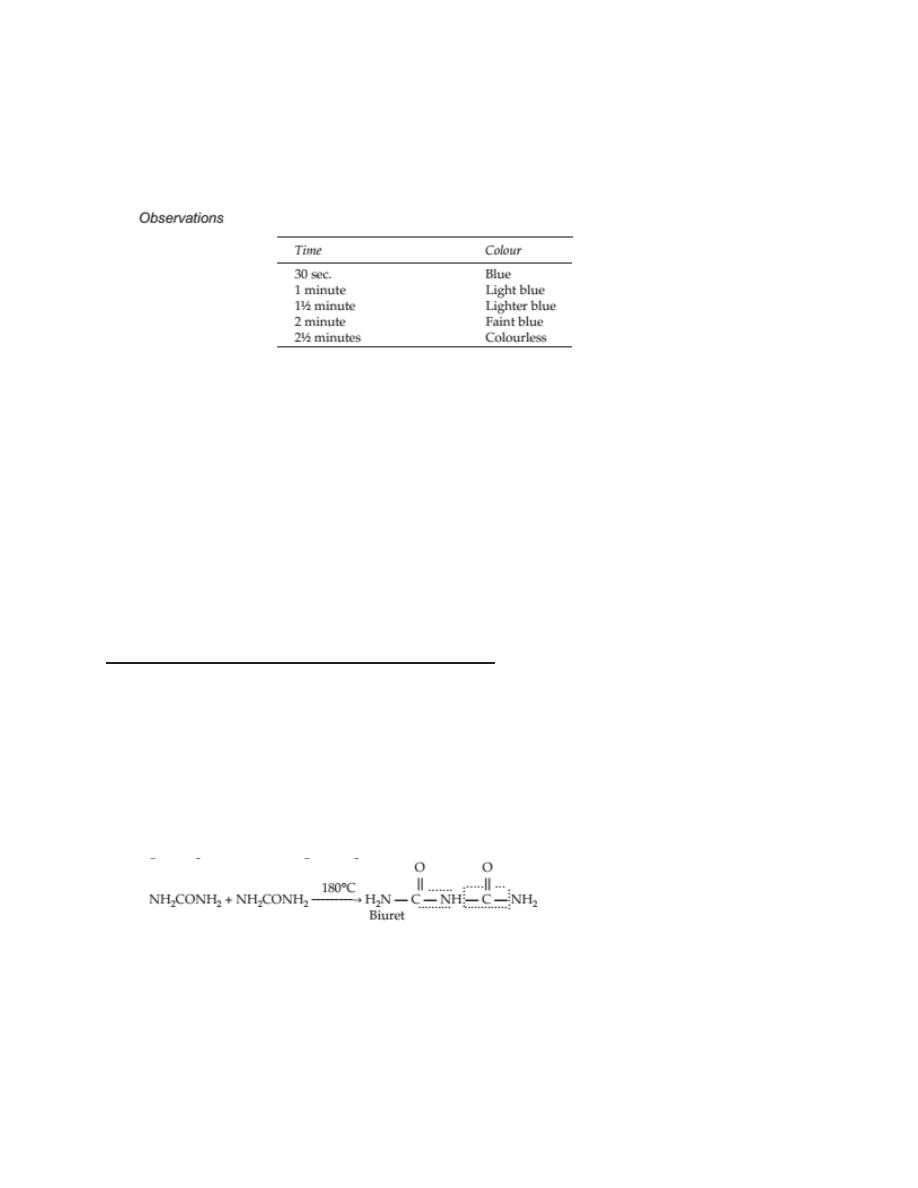

1. Gillespie’s drop method. Indicators are substances which change in colour