Poisoning

Acute poisoning accounts for ~1% of hospital admissions in the UK. In developed countries, intentional self-harm using prescribed or ‘over-the-counter’ medicines is most common, with paracetamol, antidepressants and drugs of misuse being the most frequently used.Poisoning is a major cause of death in young adults, usually before hospital admission.

Accidental poisoning is also common in children and the elderly. In developing countries, self-harm with organophosphorus pesticides and herbicides is endemic, and frequently fatal.

General approach to the poisoned patient

In envenomed patients, establish:● When was the patient exposed to the bite/sting?

● What did the causal organism look like?

● How did it happen?

● Were there multiple bites/stings?

● What first aid was given?

● What are the patient’s symptoms?

● Do they have other medical conditions, regular treatments, previous similar episodes or known allergies?

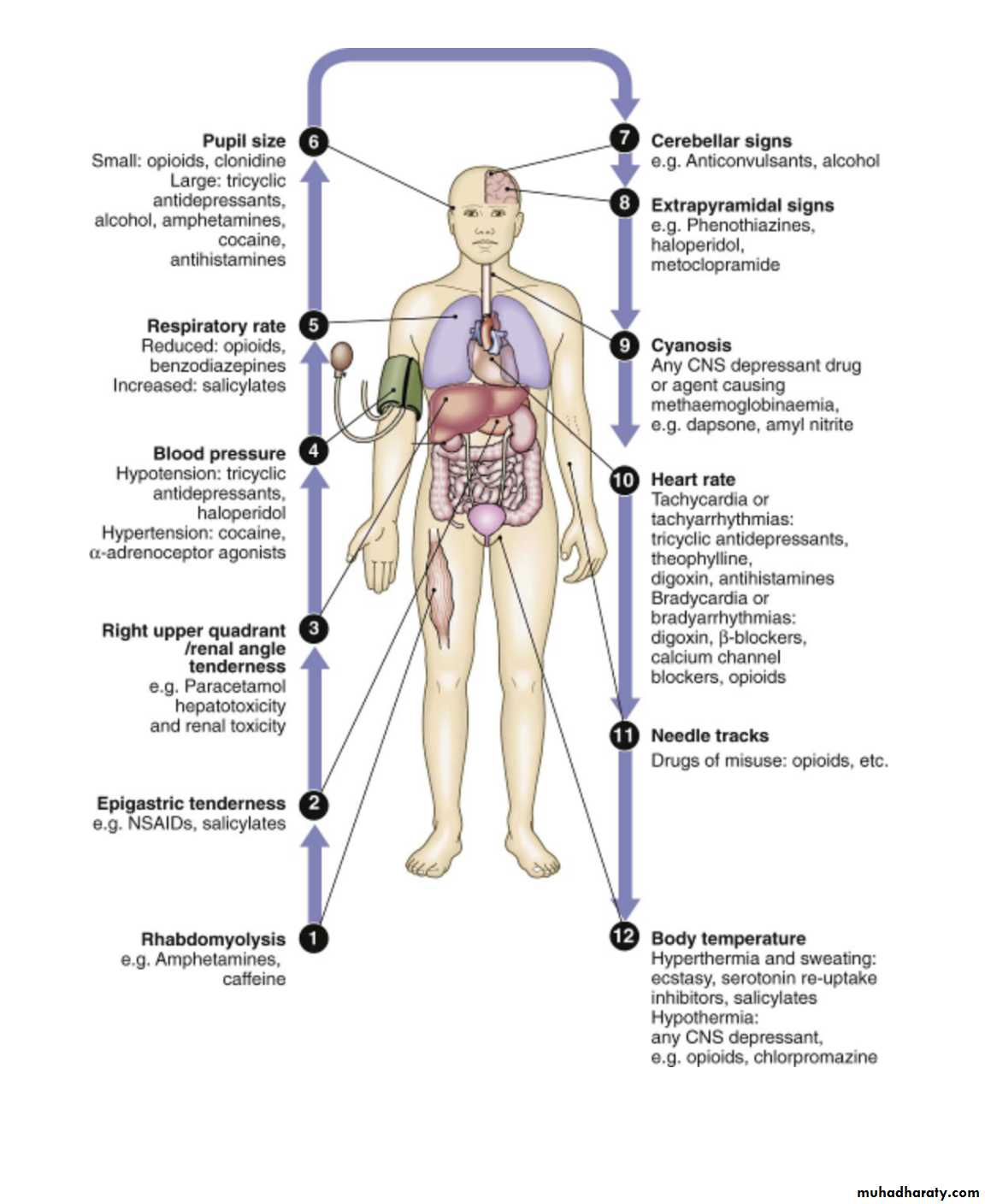

Clinical examination

There may be needle marks or evidence of previous self-harm, e.g. razor marks on forearms.

Pupil size, respiratory rate and heart rate may help to narrow down the potential list of toxins.

The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) is most frequently used to assess the degree of impaired consciousness.

The patient’s weight helps to determine whether toxicity is likely to occur, given the dose ingested.

When patients are unconscious and no history is available, other causes of coma must be excluded (especially meningitis, intracerebral bleeds, hypoglycaemia, diabetic ketoacidosis, uraemia and encephalopathy).

Certain classes of drug cause clusters of typical signs, e.g. cholinergic or anticholinergic, sedative or opioid effects, which can aid diagnosis.

Investigations

U&Es and creatinine should be measured in all patients, and ABGs in those with circulatory or respiratory compromise.Drug levels are a useful to guide treatment for some specific toxins, e.g. paracetamol, salicylate, iron, digoxin, carboxyhaemoglobin, lithium and theophylline.

Urinary drug screens have a limited clinical role.

Psychiatric assessment

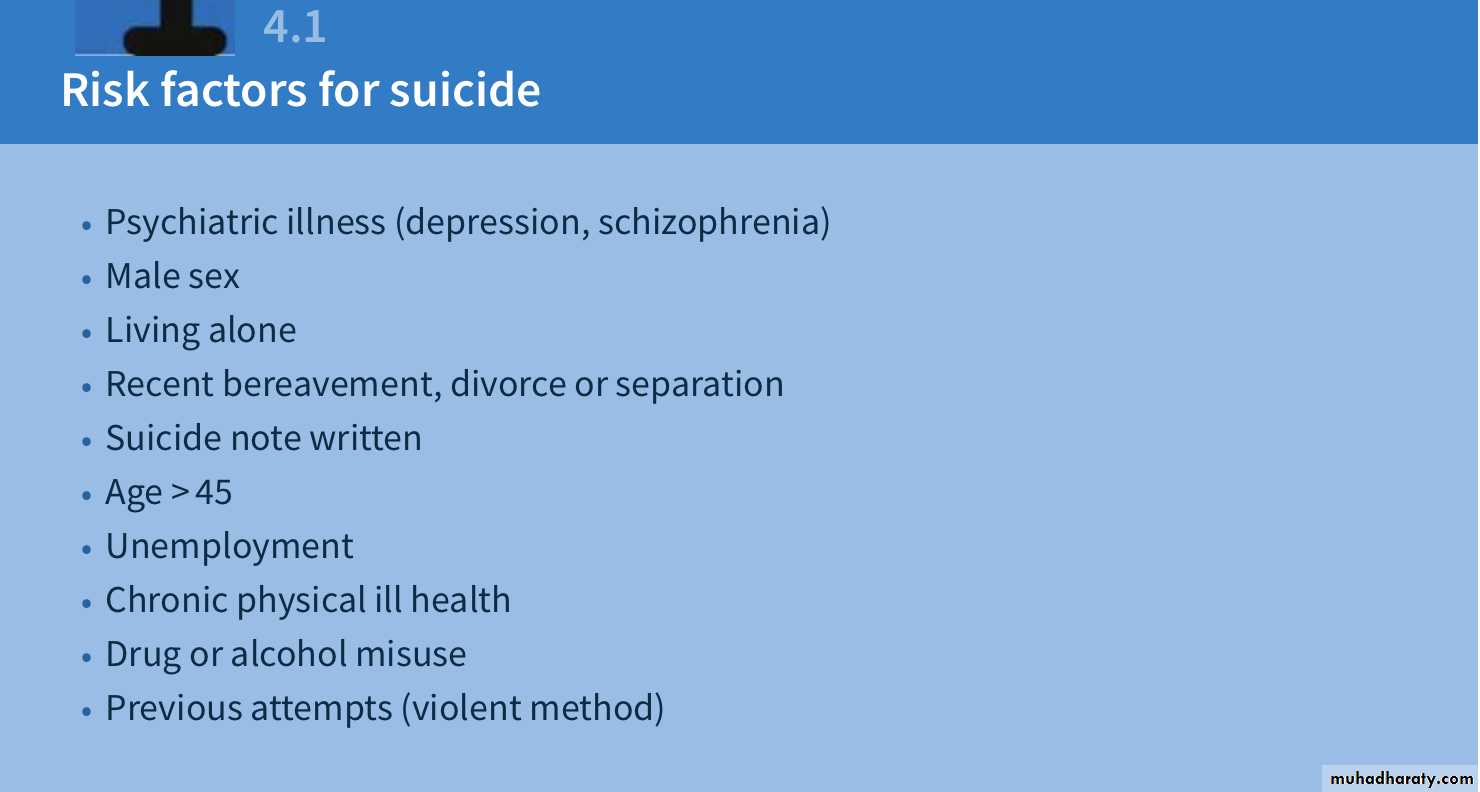

All patients who have taken a deliberate drug overdose should undergo psychiatric evaluation by a trained professional before discharge, but ideally after recovering from poisoning.The purpose is to establish the short-term risk of suicide and to identify potentially treatable problems, either medical, psychiatric or social.

Management of the poisoned patient

Eye or skin contamination should be treated with appropriate washing or irrigation.Patients who have recently ingested significant overdoses need further measures to prevent absorption or increase elimination:

Activated charcoal (50 g orally) can be given, if a potentially toxic amount of poison has been ingested < 1 hr before presentation. Agents that do not bind to activated charcoal include ethylene glycol, iron, lithium, mercury and methanol.

Whole-bowel irrigation with polyethylene glycol can be used for toxic ingestions of iron, lithium and theophylline, or to flush out packets of illicit drugs.

Urinary alkalinisation using IV sodium bicarbonate enhances elimination of salicylates, methotrexate and the herbicide 2,4-D.

Haemodialysis is occasionally used for serious poisoning with salicylates, theophylline, ethylene glycol, methanol or carbamazepine.

Infusions of lipid emulsion can be used to reduce tissue concentrations of lipid-soluble drugs such as tricyclic antidepressants.

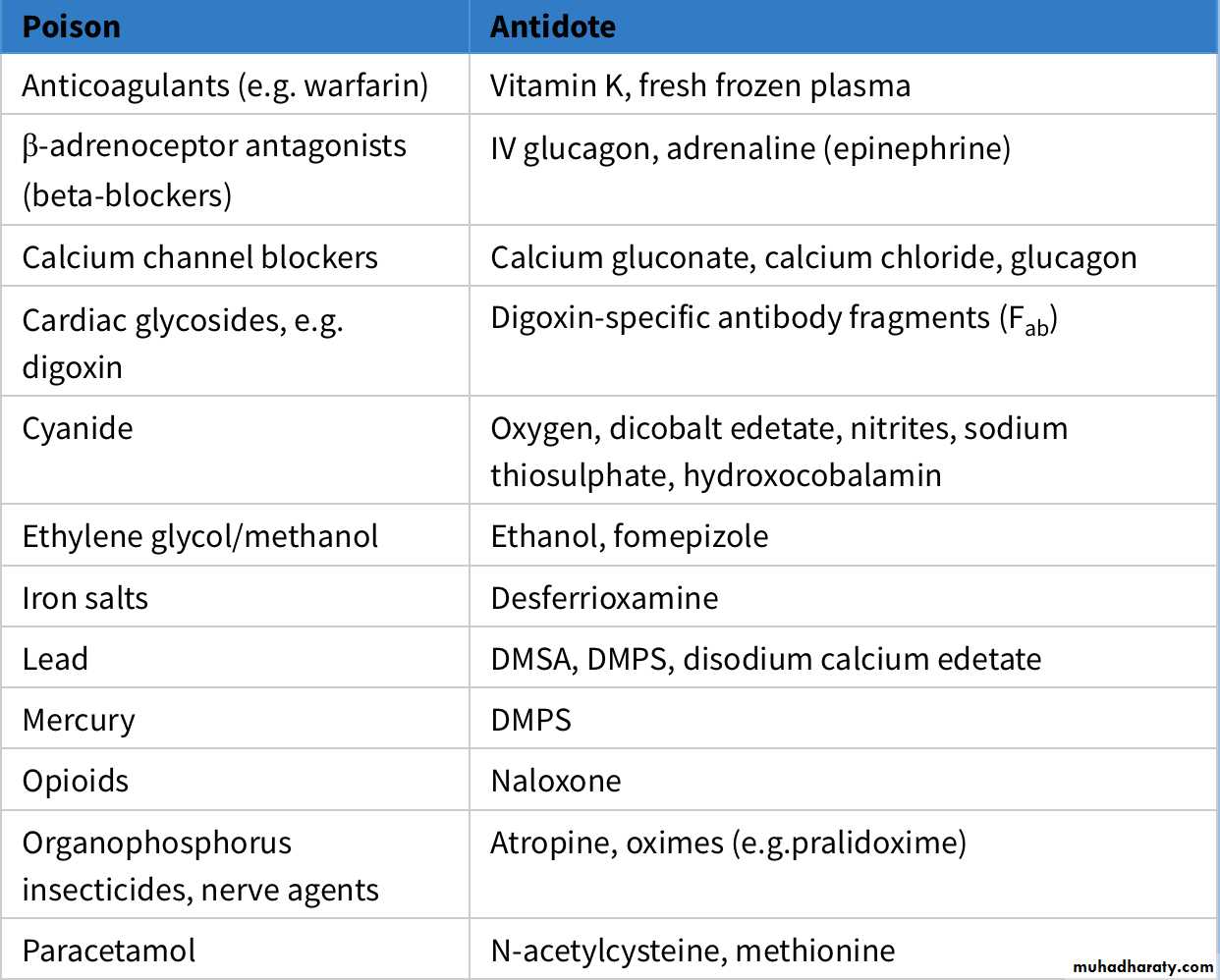

Specific antidotes are only available for a small number of poisons. In serious cases, meticulous supportive care, including the treatment of seizures, coma and arrythmias, with ventilatory support where required, is critical to good outcome.