PHASE II PERIODONTAL THERAPY

Gingival Surgical TechniquesPeriodontal pocket reduction surgery limited to the gingival tissues only and not involving the underlying osseous structures, without the use of flap surgery, can be classified as:

Gingival curettage and,

Gingivectomy.GINGIVAL CURETTAGE

The word curettage is used in periodontics to mean the scraping of the gingival wall of a periodontal pocket to remove diseased soft tissue.Curettage in periodontics has been defined as gingival and subgingival curettage.

Gingival curettage consists of the removal of the inflamed soft tissue lateral to the pocket wall and the junctional epithelium.

Subgingival curettage refers to the procedure that is performed apical to the junctional epithelium and severing the connective tissue attachment down to the osseous crest.

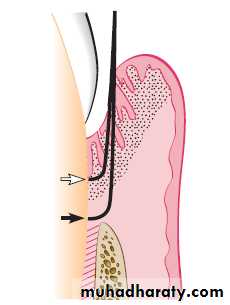

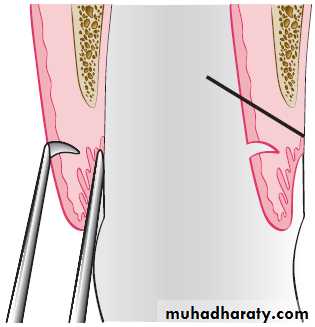

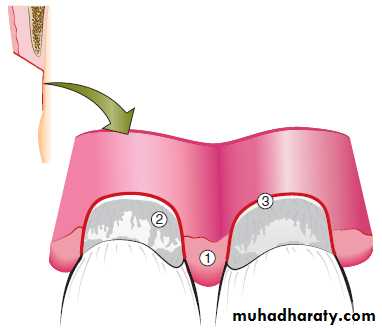

Extent of gingival curettage (white arrow) and

subgingival curettage (black arrow).

Rationale

Curettage accomplishes the removal of the chronically inflamed granulation tissue that forms in the lateral wall of the periodontal pocket. This tissue, in addition to the usual components of granulation tissues (fibroblastic and angioblastic proliferation), contains areas of chronic inflammation and may also have pieces of dislodged calculus and bacterial colonies. The latter may enhance the pathologic features of the tissue and hinder healing.This inflamed granulation tissue is lined by epithelium, and deep strands of epithelium penetrate into the tissue. The presence of this epithelium is considered as a barrier to the attachment of new fibers in the area.

When the root is thoroughly planed, the major source of bacteria disappears, and the pathologic changes in the tissues adjacent to the pocket resolve with no need to eliminate the inflamed granulation tissue by curettage.

It has been shown that scaling and root planing with additional curettage do not improve the condition of the periodontal tissues beyond the improvement resulting from scaling and root planing alone.

Curettage may also eliminate all or most of the epithelium that lines the pocket wall and the underlying junctional epithelium. Curettage for this purpose is still valid, particularly when an attempt is made for new attachment, as occurs in intrabony pockets.

Curettage and Esthetics

Esthetics is a major consideration of therapy, especially in the maxillary anterior area, and every effort is made to minimize gingival tissue shrinkage and the preservation of the interdental papilla.A compromise therapy is feasible in the anterior maxilla; this therapy consists of thorough subgingival root planing while attempting to not detach the connective tissue attachment beneath the junctional epithelium. Gingival curettage should be avoided. The granulation tissue in the lateral wall of the pocket, in an environment free of plaque and calculus, becomes connective tissue, thereby minimizing gingival shrinkage. Thus, although complete pocket elimination is not accomplished, the inflammatory changes are reduced or eliminated and the interdental papilla and the esthetic appearance of the area are preserved.

When a surgical flap is necessary for access to the root surface for scaling and root planing, the papilla preservation technique is used to minimize gingival recession and preserve the interdental papilla .

Another important precaution is to avoid root planing apical to the base of the pocket to the osseous crest The removal of the junctional epithelium and disruption of the connective tissue attachment exposes the nondiseased portion of the cementum. Root planing and the removal of the nondiseased cementum may result in excessive shrinkage of the gingiva, which results in increased gingival recession.

Indications

1. Curettage can be performed as part of new attachment attempts in moderately deep intrabony pockets located in accessible areas in which a nonflap type of “closed” surgery is indicated.

2. Curettage can be attempted as a nondefinitive procedure to reduce inflammation when aggressive surgical techniques (e.g., flaps) are contraindicated in patients because of their age, systemic problems, psychologic problems, or other factors. As the prognosis is impaired in these patients, the clinician should attempt this approach only when the indicated surgical techniques cannot be performed and both the clinician and the patient have a clear understanding of its limitations.

3. Curettage is frequently performed on recall visits as a method of maintenance treatment for areas of recurrent inflammation and pocket depth.

Procedure

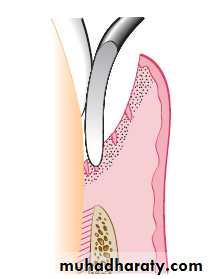

Basic Technique. Curettage does not eliminate the causes of inflammation (i.e., bacterial plaque and deposits). Therefore curettage should always be preceded by scaling and root planing, which is the basic periodontal therapy procedure. Gingival curettage always requires some type of local anesthesia.The curette is selected so that the cutting edge is against the tissue. The instrument is inserted to engage the inner lining of the pocket wall and is carried along the soft tissue, usually in a horizontal stroke. The pocket wall may be supported by gentle finger pressure or swab on the external surface.

The curette is then placed under the cut edge of the junctional epithelium to undermine it.

Gingival curettage performed with a horizontal stroke of the curette.

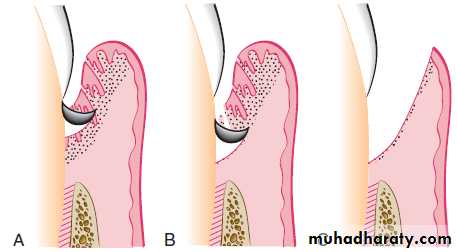

In subgingival curettage, the tissues attached between the bottom of the pocket and the alveolar crest are removed with a scooping motion of the curette to the tooth surface.The area is flushed to remove debris, and the tissue is partly adapted to the tooth by gentle finger pressure. In some cases, suturing of separated papillae and application of a periodontal pack may be indicated.

Subgingival curettage. A, Elimination of pocket lining. B, Elimination of junctional epithelium and granulation tissue. C, Procedure completed.

OTHER TECHNIQUES

Excisional New Attachment Procedure1. After adequate anesthesia, make an internal bevel incision from the margin of the free gingiva apically to a point below the bottom of the pocket. The intention is to cut the inner portion of the soft tissue wall of the pocket, all around the tooth.

2. Remove the excised tissue with a curette, and carefully perform root planing on all exposed cementum to achieve a smooth, hard consistency. Preserve all connective tissue fibers that remain attached to the root surface.

3. Approximate the wound edges; if they do not meet passively, recontour the bone until good adaptation of thewound edges is achieved. Place sutures and a periodontal dressing.

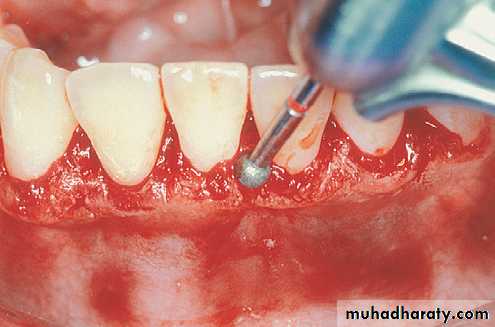

Ultrasonic Curettage.

Ultrasound is effective for debriding the epithelial lining of periodontal pockets. This results in a narrow band of necrotic tissue (microcauterization), which strips off the inner lining of the pocket.The scaler-shaped and rod-shaped ultrasonic instruments are used for this purpose. Some investigators found ultrasonic instruments to be as effective as manual instruments for curettage but resulted in less inflammation and less removal of underlying connective tissue. The gingiva can be made more rigid for ultrasonic curettage by injecting anesthetic solution directly into it

Caustic Drugs.

The use of caustic drugs has been recommended to induce a chemical curettage of the lateral wall of the pocket or even the selective elimination of the epithelium. Drugs, such as sodium sulfide, alkaline sodium hypochlorite solution (Antiformin), and phenol, have been proposed and then discarded after studies indicated their ineffectiveness. The extent of tissue destruction with these drugs cannot be controlled, and they may increase rather than reduce the amount of tissue to be removed by enzymes and phagocytes.Healing after Scaling and Curettage

Immediately after curettage, a blood clot fills the pocket area, which is totally or partially devoid of epithelial lining. Hemorrhage is also present in the tissues with dilated capillaries and abundant polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs), which appear on the wound surface.This is followed by a rapid proliferation of granulation tissue with a decrease in the number of small blood vessels as the tissue matures.

Restoration and epithelialization of the sulcus generally require 2 to 7 days, and restoration of the junctional epithelium occurs in animals as early as 5 days after treatment.

Immature collagen fibers appear within 21 days. Healthy gingival fibers inadvertently severed from the tooth and tears in the epithelium are repaired in the healing process. Experimental studies have reported that healing results in the formation of a long, thin junctional epithelium with no new connective tissue attachment. In some cases, this long epithelium is interrupted by “windows” of connective tissue attachment.

Clinical Appearance after Scaling and Curettage

Immediately after scaling and curettage, the gingiva appears hemorrhagic and bright red. After 1 week, the gingiva appears reduced in height because of an apical shift in the position of the gingival margin. The gingiva is also darker red than normal but much less so than on previous days.After 2 weeks and with proper oral hygiene, the normal color, consistency, surface texture, and contour of the gingiva are attained and the gingival margin is well adapted to the tooth.

GINGIVECTOMY

Gingivectomy means excision of the gingiva. By removing the pocket wall, gingivectomy provides visibility and accessibility for complete calculus removal and thorough smoothing of the roots. This creates a favorable environment for gingival healing and restoration of a physiologic gingival contour.The gingivectomy technique was widely performed in the past. Improved understanding of healing mechanisms and the development of more sophisticated flap methods have relegated the gingivectomy to a lesser role in the current techniques. However, it remains an effective form of treatment when indicated.

Indications

1. Elimination of suprabony pockets, regardless of their depth, if the pocket wall is fibrous and firm.2. Elimination of gingival enlargements.

3. Elimination of suprabony periodontal abscesses.

Contraindications

1. The need for bone surgery or examination of the bone shape and morphology.2. Situations in which the bottom of the pocket is apical to the mucogingival junction.

3. Esthetic considerations, particularly in the anterior maxilla.

Instruments

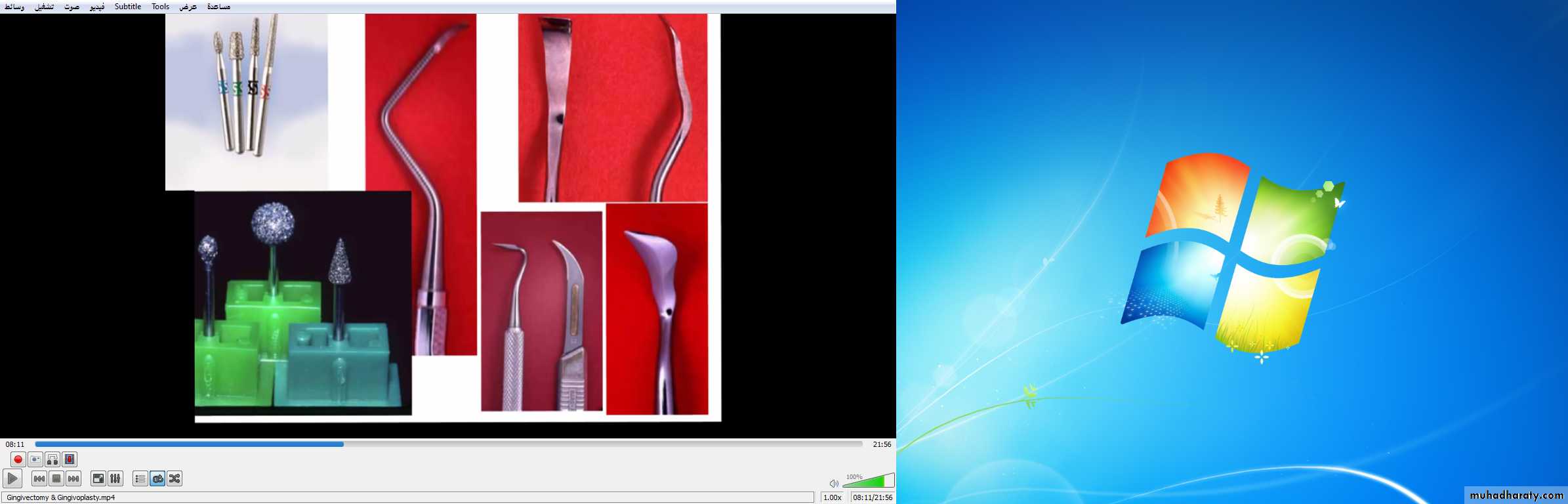

Surgical GingivectomyThe gingivectomy technique may be performed by means of scalpels, electrodes, lasers, or chemicals.

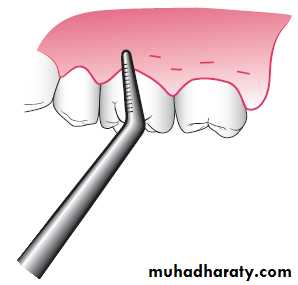

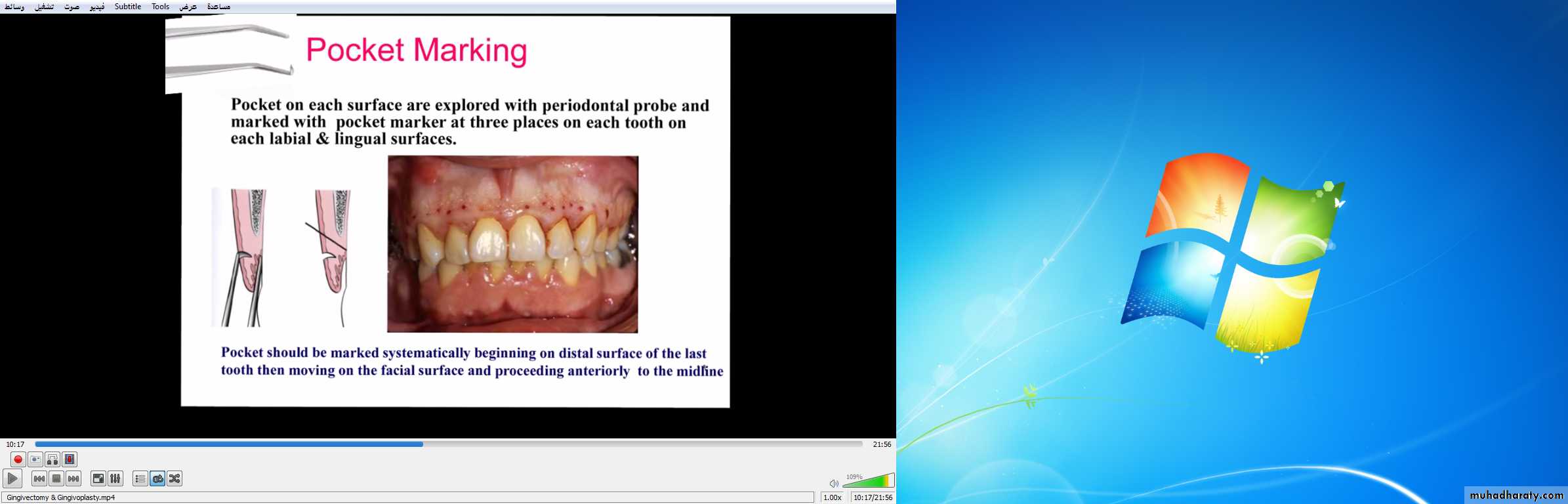

Step 1. The pockets on each surface are explored with a periodontal probe and marked with a pocket marker. Each pocket is marked in several areas to outline its course on each surface.

Step 2. Periodontal knives (e.g., Kirkland knives) are used for

incisions on the facial and lingual surfaces and those distal to the terminal tooth in the arch. Orban periodontal knives are used for interdental incisions. Bard-Parker blades #12 and #15, as well as scissors, are used as auxiliary instruments.The incision is started apical to the points marking the course of the pockets and is directed coronally to a point between the base of the pocket and the crest of the bone. It should be as close as possible to the bone without exposing it, to remove the soft tissue coronal to the bone. Exposure of bone is undesirable. If it occurs, healing usually presents minimal complications if the area is adequately covered by the periodontal pack.

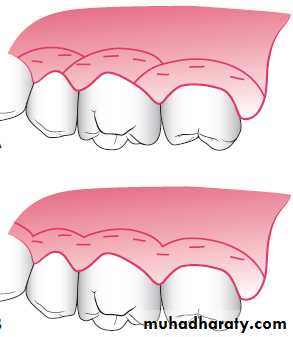

Either interrupted or continuous incisions may be used. The incision should be beveled at approximately 45 degrees to the tooth surface and recreate the normal festooned pattern of the gingiva. Failure to bevel the incision will leave a broad, fibrous plateau, which will take a longer time to develop a physiologic contour. In the interim, plaque and calculus may lead to the recurrence of pockets.

Step 3. Remove the excised pocket wall, clean the area, and

closely examine the root surface. The most apical zone consists of a light, band-like zone where the tissues were attached. Coronally, calculus remnants, root caries, or resorption may be found. Granulation tissue may be seen on the excised soft tissue.Field of operation immed-iately after removing pocket wall.

1, Granulation tissue;2, calculus and other root deposits;

3, clear space where junctional epithelium was attached.

Step 4. Carefully curette the granulation tissue and remove any remaining calculus and necrotic cementum to leave a smooth and clean surface.

Step 5. Cover the area with a surgical pack

Clinical Case: Surgical treatment of cyclosporine induced gingival enlargement using the gingivectomy technique on a 16-year-old girl who had received a kidney allograft 2 years earlier.

A, Presence of enlarged gingival tissues and pseudopocket forma-tion; no attachment loss or evid-ence of vertical bone loss existed.

B, Initial external bevel incision performed with a Kirkland knife.

C, Interproximal tissue release achieved with an Orban knife. D and E, Gingivoplasty performed with tissue nippers and a round diamond at high speed with abundant refrigeration

C

D

F

E

G, Placement of noneugenol periodontal dressing.

H, Surgical area 3 months postoperativelyGingivoplasty

Gingivoplasty is similar to gingivectomy, but its objective is different. Gingivectomy is performed to eliminate periodontal pockets and includes reshaping as part of the technique. Gingivoplasty is a reshaping of the gingiva to create physiologic gingival contours with the sole purpose of recontouring the gingiva in the absence of pockets.Gingival and periodontal disease often produces deformities in the gingiva that is conducive for plaque accumulation and food debris, which prolongs and aggravates the disease process. Such deformities include (1) gingival clefts and craters, (2) craterlike interdental papillae caused by acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis, and (3) gingival enlargements.

Gingivoplasty may be accomplished with a periodontal knife, a scalpel, rotary coarse diamond stones, or electrodes. The technique resembles that of festooning of a artificial denture, which consists of tapering the gingival margin, creating a scalloped marginal outline, thinning the attached gingiva , creating vertical interdental grooves, and shaping the interdental papillae.

Healing after Surgical Gingivectomy

The initial response after gingivectomy is the formation of a protective surface blood clot. The underlying tissue becomes acutely inflamed with necrosis. The clot is then replaced by granulation tissue.In 24 hours, there is an increase in new connective tissue cells, which are mainly angioblasts beneath the surface layer of inflammation and necrotic tissue.

By the third day, numerous young fibroblasts are located in the area. The highly vascular granulation tissue grows coronally, creating a new free gingival margin and sulcus. Capillaries derived from blood vessels of the periodontal ligament migrate into the granulation tissue and within 2 weeks, they connect with the gingival vessels.

After 12 to 24 hours, epithelial cells at the margins of the wound begin to migrate over the granulation tissue, separating it from the contaminated surface layer of the clot. Epithelial activity at the margins reaches a peak in 24 to 36 hours.

The new epithelial cells arise from the basal and deeper spinous layers of the epithelial wound edge and migrate over the wound over a fibrin layer that is later resorbed and replaced by a connective tissue bed. The epithelial cells advance by a tumbling action with the cells becoming fixed to the substrate by hemidesmosomes and a new basement lamina.

After 5 to 14 days, surface epithelialization is generally complete. During the first 4 weeks after gingivectomy, keratinization is less than it was before surgery. Complete epithelial repair takes about 1 month. Vasodilation and vascularity begin to decrease after the fourth day of healing and appear to be almost normal by the sixteenth day. Complete repair of the connective tissue takes about 7 weeks.

The flow of gingival fluid in humans is initially increased after

gingivectomy and diminishes as healing progresses. Maximal flow is reached after 1 week, coinciding with the time of maximal inflammation.Although the tissue changes that occur in post-gingivectomy

healing are the same in all individuals, the time required for complete healing varies considerably, depending on the area of the incised surface and interference from local irritation and infection. In patients with physiologic gingival melanosis, the pigmentation is diminished in the healed gingiva.Gingivectomy is rarely used to treat periodontitis and even patients with extensive gingival hyperplasia are best treated with flap surgery so that the underlying bone defects can be visualized, treated, and then covered with soft tissue. A few patients needing crown lengthening can be treated with gingivectomy when there is no need for osseous surgery to establish an adequate biologic width.

Laser gingivectomy with carbon dioxide (CO2) laser or Nd-YAG laser gives a more precise tissue contouring than tissue removal with surgical blades and may be another treatment option. Electrosurgical gingivectomies may cause delayed healing, and the surgeon must be careful not to place the electrodes close to the bone margins because sequestration of bone can occur.

Current periodontal surgery must consider the (1) conservation of keratinized gingiva, (2) minimal gingival tissue loss to maintain esthetics, (3) adequate access to the osseous defects for definitive defect correction, and (4) minimal postsurgical discomfort and bleeding by attempting surgical procedures that will allow primary closure. The gingivectomy surgical technique has limited use in current surgical therapy because it does not satisfy these considerations in periodontal therapy. The clinician must carefully evaluate each case as to the proper application of this surgical procedure.