Lecture 9 Dr. Janan Alrefaee

Control of calcium excretion by the kidneys

Normally, about 99 % of the filtered calcium is reabsorbed by the tubules [65% by proximal

tubule, 25 to 30 % by loop of Henle & 4 to 9 % by distal and collecting tubules (as sodium)]

& about 1 % is excreted. Calcium excretion is adjusted to meet the body’s needs.

Factors that modify renal calcium excretion

1- Parathyroid hormone (PTH). Increase PTH level, will increase calcium reabsorption &

reduce its urinary excretion and vice versa.

2- Extracellular volume expansion or increased arterial pressure will decrease proximal

tubule calcium reabsorption and increase its urinary excretion and vice versa.

3- Plasma phosphate concentration increases stimulate PTH (effect as above) and vice

versa.

4- Metabolic acidosis stimulates calcium reabsorption and metabolic alkalosis inhibits

calcium reabsorption.

Control of renal phosphate excretion:

The renal tubules have a normal transport maximum for reabsorbing phosphate of about 0.1

mM/min. This TM increase with low phosphate diet over time and reduce phosphate

excretion in urine.

●increase plasma PTH, will decrease tubular phosphate reabsorption and more phosphate is

excreted.

mM= Millimolar

Control of renal magnesium excretion and extracellular magnesium ion concentration

The total plasma magnesium concentration is about 1.8 mEq/L, the free ionized

concentration of magnesium is only about 0.8 mEq/L.

The filtered magnesium is reabsorbed about 25 % by proximal tubule, 65 % by loop of Henle

& less than 5 % by distal and collecting tubules.

The kidneys normally excrete about 10 to 15 % of the glomerular filtrate magnesium, this

can modify depending on magnesium excess or depletion.

Magnesium excretion is increased during following disturbance: (1) increased ECF

magnesium conc. (2) extracellular volume expansion, and (3) increased ECF calcium conc.

Integration of renal mechanisms for control of extracellular fluid

When intra-renal compensations are exhausted (in disease), the systemic mechanisms operate

together to control sodium and water balance and so control extracellular fluid volume and

homeostasis by as fallow:

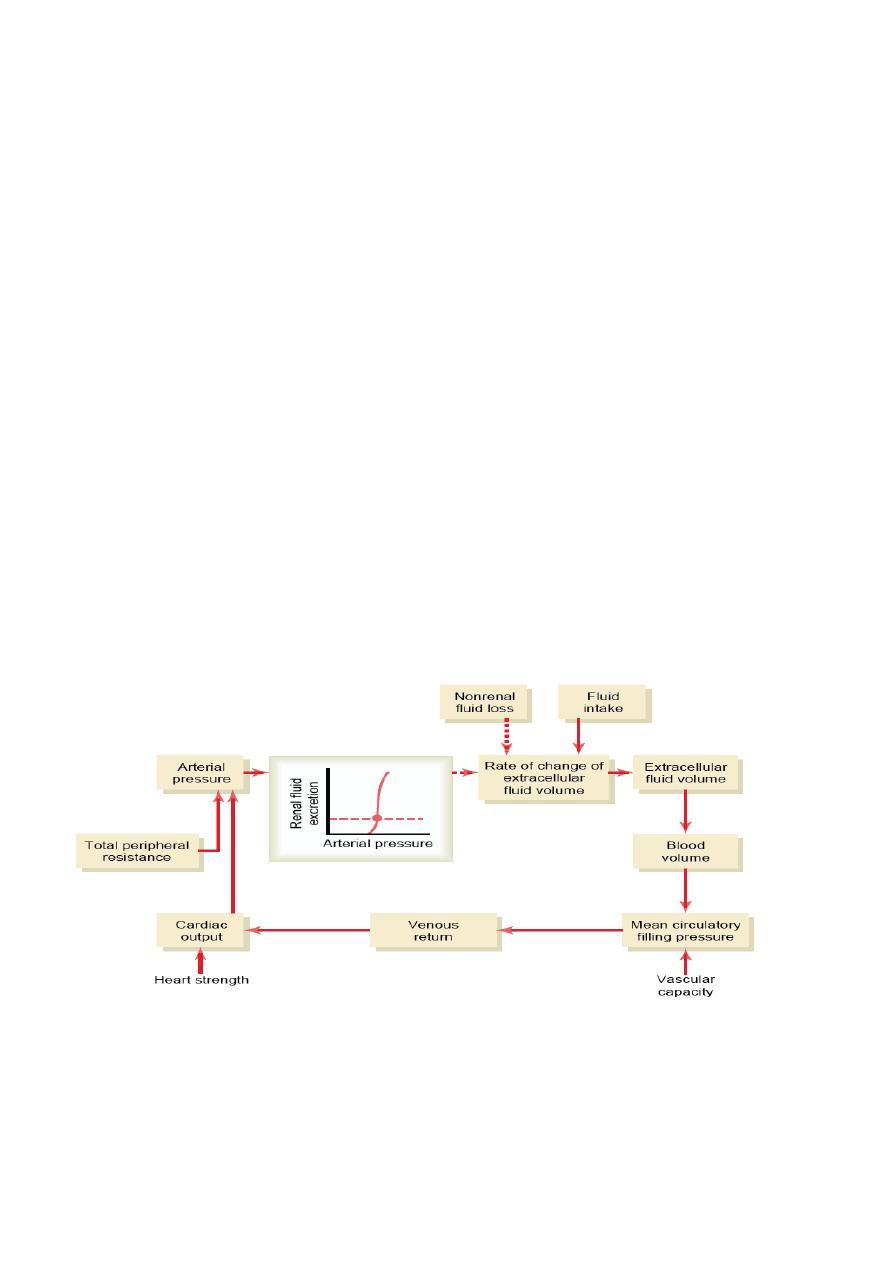

1- Changes in blood pressure (as Pressure natriuresis) is enhanced (Fig. 9-1).

2- Changes in circulating hormones such as renin-angiotensin systemin is enhanced,

aldosterone, ADH and atrial natriuretic peptide.

3- Alterations of sympathetic nervous system activity. Eating a meal contains large amounts

of salt and water

inhibition of renal sympathetic activity & the rapid elimination of excess

fluid in the circulation.

Integrated responses to changes in sodium intake normally

The kidneys match salt and water excretion to salt and water intakes that can range from as

low as one tenth of normal to as high as 10 times normal.

As sodium intake is increased, sodium output initially delays slightly behind intake. The time

delay results a slight increase in extracellular fluid volume & small increases in arterial

pressure that causes various mechanisms in the body to increase sodium excretion. These

mechanisms include the following:

1. Activation of low pressure receptor reflexes that originate from the stretch receptors of the

right atrium and the pulmonary blood vessels, this give signals to the brain stem to inhibit

sympathetic nerve activity to the kidneys to decrease tubular sodium reabsorption.

This mechanism is most important in the first few hours—or perhaps the first day—after a

large increase in salt and water intake.

2. Pressure natriuresis.

3. Suppression of angiotensin II formation which in turn decreases aldosterone secretion,

both lead to reduce tubular sodium reabsorption.

4. Stimulation of natriuretic systems, especially ANP.

The opposite changes take place when sodium intake is reduced below normal levels.

Fig-9.1 Basic renal–body fluid feedback mechanism (Solid lines indicate positive effects,

and dashed lines indicate negative effects).

Physiologic anatomy of the bladder

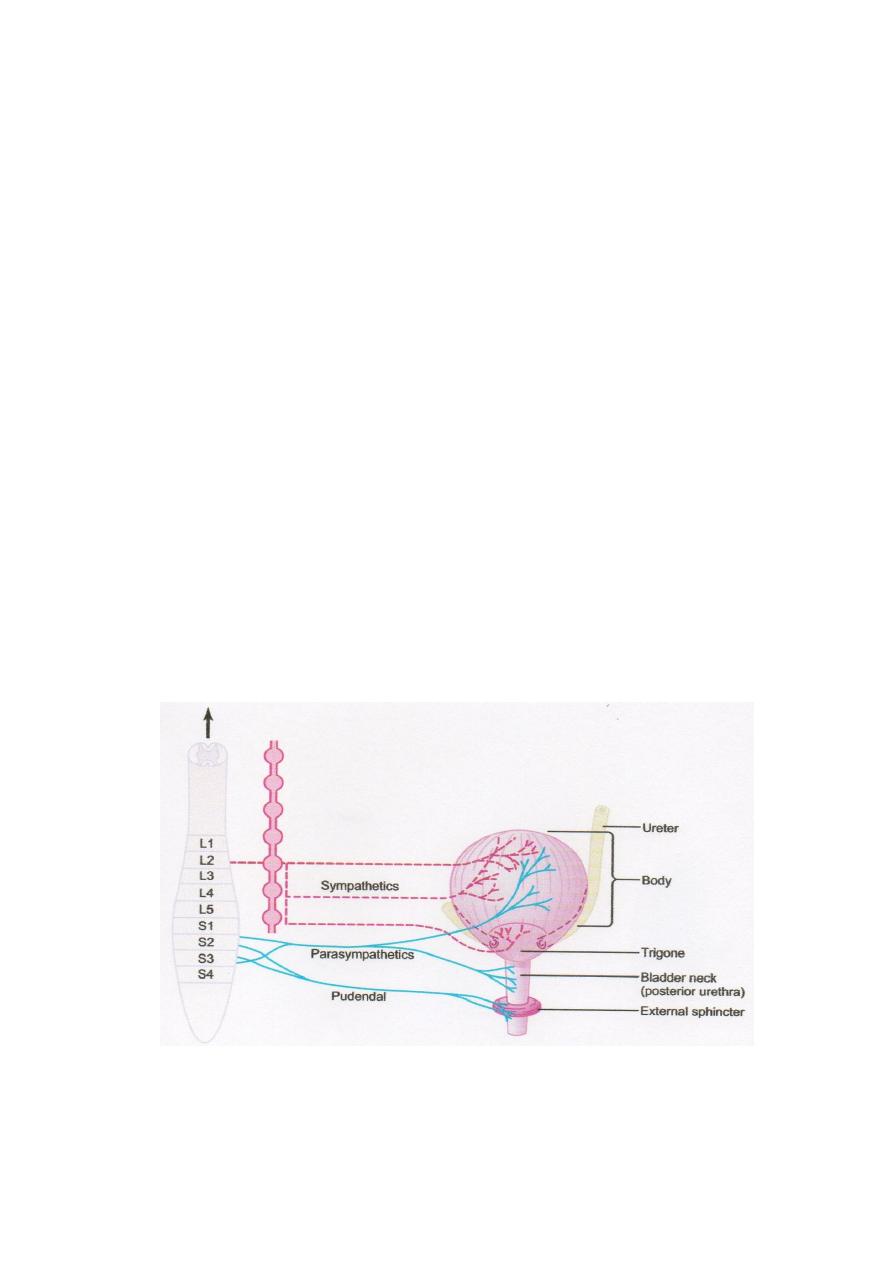

The urinary bladder (Fig.9.2) is a smooth muscle chamber composed of two main parts: (1)

the body, which is the major part of the bladder in which urine collects, and (2) the neck,

which is a funnel-shaped extension of the body, passing inferiorly and anteriorly into the

urogenital triangle and connecting with the urethra. The lower part of the bladder neck is also

called the posterior urethra because of its relation to the urethra. The smooth muscle of the

bladder is called the detrusor muscle. Its muscle fibers extend in all directions and, when

contracted, can increase the pressure in the bladder to 40 to 60 mm Hg. Thus, contraction of

the detrusor muscle is a major step in emptying the bladder. Smooth muscle cells of the

detrusor muscle fuse with one another. Therefore, an action potential can spread throughout

the detrusor muscle, from one muscle cell to the next, to cause contraction of the entire

bladder at once. On the posterior wall of the bladder, lying immediately above the bladder

neck, is a small triangular area called the trigone. At the lower most apex of the trigone, the

bladder neck opens into the posterior urethra, and the two ureters enter the bladder at the

uppermost angles of the trigone. The trigone mucosa is smooth, in contrast to the remaining

bladder mucosa, which is folded to form rugae. Each ureter, as it enters the bladder, courses

obliquely through the detrusor muscle and then passes another 1 to 2 cm beneath the bladder

mucosa before emptying into the bladder. The bladder neck (posterior urethra) is 2 to 3 cm

long, and its wall is composed of detrusor muscle interlaced with a large amount of elastic

tissue. The muscle in this area is called the internal sphincter. Its natural tone normally keeps

the bladder neck and posterior urethra empty of urine and, therefore, prevents emptying of

the bladder until the pressure in the main part of the bladder rises above a critical threshold.

Beyond the posterior urethra, the urethra passes through the urogenital diaphragm, which

contains a layer of voluntary skeletal muscle called the external sphincter of the bladder. The

external sphincter muscle is under voluntary control of the nervous system and can be used

to consciously prevent urination even when involuntary controls are attempting to empty the

bladder.

Figure-9.2. Urinary bladder and its innervation