د. بشار باطنية 20\3\2018

عدد الاوراق( 6 ) م\3\موصل lec:1+2Abnormal gait

Seeing a patient walk can be very revealing for neurological diagnosis and is an important element of assessing disability. Patterns of weakness, loss of coordination and proprioceptive sensory loss produce a range of abnormal gaits .Abnormal gait

Neurogenic gait disorders need to be distinguished from those due to skeletal abnormalities, usually characterised by pain producing an antalgic gait, or limp. Gaits that do not fit either pattern may be due to psychiatric disorders and are usually incompatible with any anatomical or physiological deficit .

Pyramidal gait

Upper motor neuron (pyramidal) lesions cause a gait in which the upper limb is held in flexion and the ankle joint in the lower limb kept relatively extended. This causes a tendency for the toes to strike the ground while walking and in an attempt to overcome this, the leg is swung outwards at the hip (circumduction). In a hemiplegia, the asymmetry between the affected and normal sides is obvious in walking. In a paraparesis, both lower limbs swing slowly from the hips in extension and dragged stiffly over the ground .This can often be heard as well as seen .Foot drop

In normal walking, toe strike follows heel strike during the gait cycle.If there is a lower motor neuron lesion affecting the lower limb , weakness of ankle dorsiflexion disrupts this pattern. The result is a less controlled descent of the foot making a slapping noise.

If the distal weakness is more severe, the foot will have to be lifted higher at the knee to allow room for the inadequately dorsiflexed foot to swing through, producing a high stepping gait .

Myopathic gait

During walking, alternate transfer of the body's weight through each leg requires careful control of hip abduction by the gluteal muscles.In proximal muscle weakness, usually caused by muscle disease, the hips are not properly fixed by these muscles and trunk movements are exaggerated, producing a waddling gait .

Ataxic gait

An ataxic gait can occur as the result of lesions in the cerebellum , vestibular apparatus or peripheral nerves

Ataxic gait

Patients with lesions of the central parts of the cerebellum (the vermis) walk with a characteristic broad-based gait, 'like a drunken sailor' (cerebellar function is particularly sensitive to alcohol). Patients with acute vestibular disturbances walk in a similar broad-based fashion, though the accompanying vertigo distinguishes them from those with cerebellar lesions. Less severe degrees of cerebellar ataxia can be detected by asking the patient to walk heel to toe; patients with vermis lesions are unable to do this .Sensory ataxia

Impairment of joint position sense makes walking unreliable, especially in poor light. The feet tend to be placed on the ground with greater emphasis, presumably in an attempt to increase what proprioceptive input is available. This results in a 'stamping' gait which is often combined with foot drop when caused by a peripheral neuropathy, but it can occur in disorders of the dorsal columns in the spinal cordExtrapyramidal gait

Patients with Parkinson disease and other extrapyramidal diseases have difficulty initiating walking and difficulty controlling the pace of their gait . Patients may get stuck while trying to start walking or when walking through doorways (freezing ) .Once started they may shuffle and have problems controlling the speed of their walking and sometimes have difficulty stopping . This produces the Festinant gait ; initial stuttering steps that quickly increase in frequency while decreasing in length .INVOLUNTARY MOVEMENTS

Rest tremorThis is pathognomonic of Parkinson disease .

It is characteristically pill rolling and usually presents asymmetrically.

Tremor of the head is not a rest tremor , since this a postural tremor disappearing when the h ead is supported

Physiological tremor

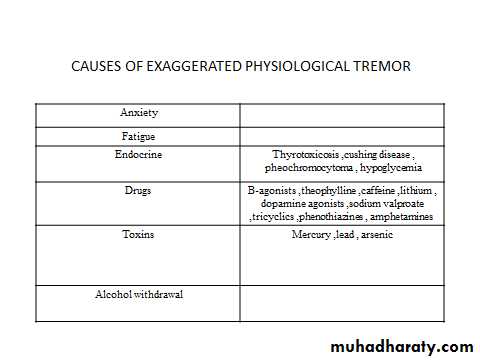

This the most common type of action trmor and occurs at a frequency of 8-12 Hz.It is common in normal subjects and exaggeration occurs in anxiety and in other situations .

Essential tremor

Essential tremor is distinct from a physiological tremor, although resembling it superficially. It is slower and may become quite disabling. The condition is often inherited, and in some families most obvious during certain specific actions such as writing or holding a glass. Alcohol often suppresses it, sometimes to the extent that the patient becomes depedent. Centrally acting β-adrenoceptor antagonists (β-blockers) such as propranolol are often effective in treatment.Intention tremor

This is characterised by oscillation at the end of a movement and typically occurs in cerebellar disease. A more dramatic intention trmor occurs with lesions in the superior cereballar peduncle (the site of the cerebellar outflow to the red nucleus).Asterixis (flapping tremor)

Asterixis, the 'flapping' tremor seen in metabolic disturbances, is the result of intermittent failure of the parietal mechanisms required to maintain a posture. Thus, when a patient is asked to hold out the arms with the hands extended at the wrists, this posture is periodically dropped, allowing the hands to drop transiently before the posture is taken up again. Occasionally, unilateral asterixis can be seen in an acute parietal lesion, usually vascular.Causes of asterixis

Renal failureLiver failure

Drug toxicity

Hypercapnia

Acute focal parietal or thalamic lesion

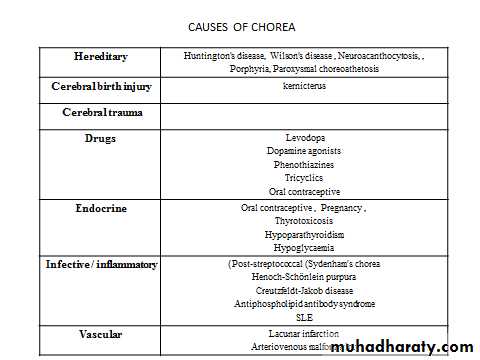

Chorea, athetosis, ballism

These are due to disturbance of balance of activity in the basal ganglia .Chorea (the Greek for 'dance') : Jerky, small-amplitude, purposeless involuntary movements . In the face, grimaces; they suggest disease in the caudate nucleus (as in Huntington's disease.

Hemiballismus: More dramatic ballistic flying violent movements of the limbs usually occur unilaterally in vascular lesions of the subthalamic structures.

Athetosis : Slower writhing movements of the limbs . These are often combined with chorea (and have a similar list of causes) and are then termed 'choreo-athetoid' movements.

Lec:

COMADefinition

Is a sleeplike state in which the patient makes no purposeful response to the environment and from which he or she cannot be aroused.

The eyes are closed and do not open spontaneously. The patient does not speak, and there is no purposeful movement of the face or limbs. Verbal stimulation produces no response.

Anatomic basis of coma

Consciousness is maintained by the normal functioning of the brainstem reticular activating system above the mid pons and its bilateral projections to the thalamus and cerebral hemispheres.

Coma results from lesions that affect either the reticular activating system or both hemispheres.

Pathophysiology

Coma results from a disturbance in the function of either the brainstem reticular activating system above the midpons or both cerebral hemispheressince these are the brain regions that maintain consciousness.

Diseases that cause no focal or lateralizing neurologic signs

A. Intoxications: alcohol, barbiturates and other sedative drugs, opiates, etc.B. Metabolic disturbances: anoxia, diabetic acidosis, uremia, hepatic failure, nonketotic hyperosmolar hyperglycemia, hypo- and hypernatremia, hypoglycemia, addisonian crisis, profound nutritional deficiency, carbon monoxide, thyroid states including Hashimoto encephalopathy

C. Severe systemic infections: pneumonia, peritonitis, typhoid fever, malaria, septicemia, WaterhouseFriderichsen syndrome.

D. Circulatory collapse (shock) from any cause.

E. Postseizure states

F. Hypertensive encephalopathy and eclampsia

G. Hyperthermia and hypothermia. state,

H. Concussion

A. Subarachnoid hemorrhage from ruptured aneurysm.

B. Acute bacterial meningitis

C. Some forms of viral encephalitis

Diseases that cause focal brainstem or lateralizing cerebral signs

A. Hemispheral hemorrhage or massive infarctionB. Brainstem infarction due to basilar artery thrombosis or

embolism

C. Brain abscess, subdural empyema, Herpes encephalitis

D. Epidural and subdural hemorrhage and brain contusion

E. Brain tumor

F. Cerebellar and pontine hemorrhage.

G. Miscellaneous: cortical vein thrombosis, viral encephalitis (herpes), focal embolic infarction due

bacterial endocarditis,

APPROACH TO DIAGNOSIS

The approach to diagnosis of the comatose patient consists first ofemergency measures to stabilize the patient and treat certain life-threatening disorders,

followed by

efforts to establish an etiologic diagnosis.

Ensure patency of the airway and adequacy of ventilation and circulation

If the airway is obstructed, the obstruction should be cleared and the patient intubated. If there is evidence of trauma that may have affected the cervical spine, however, the neck should not be moved until this possibility has been excluded by x-rays of the cervical spine. In this case, if intubation is required, it should be performed by tracheostomy. Adequacy of ventilation can be established by the absence of cyanosis, a respiratory rate greater than 8/min, the presence of breath sounds on auscultation of the chest, and the results of arterial blood gas and pH studies . If any of these suggest inadequate ventilation, the patient should be ventilated mechanically. Measurement of the pulse and blood pressure provides a rapid assessment of the status of the circulation. Circulatory embarrassment should be treated with intravenous fluid replacement, pressors, and antiarrhythmic drugs, as indicated.

Insert an intravenous catheter and withdraw blood for laboratory studies

These studies should include measurement of serum glucose and electrolytes, hepatic and renal function tests, prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and a complete blood count. Extra tubes of blood should also be obtained for additional studies that may be useful in certain cases, such as drug screens, and for tests that become necessary as diagnostic evaluation proceeds.

Begin an intravenous infusion and administer dextrose, thiamine, and naloxone

Every comatose patient should be given 25 g of dextrose intravenously, typically as 50 mL of a 50% dextrose solution, to treat possible hypoglycemic coma. Since administration of dextrose alone may precipitate or worsen Wernicke's encephalopathy in thiamine-deficient patients, all comatose patients should also receive 100 mg of thiamine by the intravenous route. To treat possible opiate overdose, the opiate antagonist naloxone, 0.4–1.2 mg intravenously, should also be administered routinely to comatose patients.

Withdraw arterial blood for blood gas and pH determinations

In addition to assisting in the assessment of ventilatory status, these studies can provide clues tometabolic causes of coma

Institute treatment for seizures, if present

Persistent or recurrent seizures in a comatose patient should be considered to represent status epilepticus and

treated accordingly

HistoryThe most crucial aspect of the history is the time over which coma develops

1- A sudden onset of coma suggests a vascular origin, especially a brainstem stroke or subarachnoid hemorrhage.2- Rapid progression from hemispheric signs, such as hemiparesis, hemisensory deficit, or aphasia, to coma within minutes to hours is characteristic of

intracerebral hemorrhage.

3- A more protracted course leading to coma (days to a week or more) is seen with tumor, abscess, or chronic subdural hematoma.

4- Coma preceded by a confusional state or agitated delirium, without lateralizing signs or symptoms, is probably due to a metabolic derangement.

Lateralizing (Focal ) Signs

1- Assymmetry of pupils.

2- Squint

3- Assymmetry of the face

4- Gaze palsy

5- Assymmetry of motor response, reflexes & plantar response

General Physical Examination

A. SIGNS OF TRAUMA1- Inspection of the head may reveal signs of basilar skull fracture, including the following:

a. Raccoon eyes—Periorbital ecchymoses.

b. Battle's sign—Swelling and discoloration overlying the mastoid bone behind the ear.

c. Hemotympanum—Blood behind the tympanic membrane.

d. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) rhinorrhea or otorrhea—Leakage of CSF from the nose or ear. CSF rhinorrhea must be distinguished from other causes of rhinorrhea, such as allergic rhinitis. It has been suggested that CSF can be distinguished from nasal mucus by the higher glucose content of CSF, but this is not always the case.

The chloride level may be more useful, since CSF chloride concentrations are 15–20 meq/L higher than those in mucus.

2- Palpation of the head may demonstrate a depressed skull fracture or swelling of soft tissues at the site of trauma.

B. BLOOD PRESSURE

Elevation of blood pressure in a comatose patient may reflect long-standing hypertension, which predisposes to intracerebral hemorrhage or stroke. In the rare condition of hypertensive encephalopathy, the blood pressure is above 250/150 mm Hg in chronically hypertensive patients.Elevation of blood pressure may also be a consequence of the process causing the coma, as in intracerebral or subarachnoid hemorrhage or, rarely, brainstem stroke.

C. TEMPERATURE

Hypothermia can occur in coma caused by ethanol or sedative drug intoxication, hypoglycemia, Wernicke's encephalopathy, hepatic encephalopathy, and myxedema.

Coma with hyperthermia is seen in heat stroke, status epilepticus, malignant hyperthermia related to inhalational anesthetics, anticholinergic drug intoxication, pontine

hemorrhage, and certain hypothalamic lesions.

D- Examination of skin

Pallor, Jaundice, Cyanosis, Purpura, Needle marks, Pigmentations…etc.

C. TEMPERATURE

Hypothermia can occur in coma caused by ethanol or sedative drug intoxication, hypoglycemia, Wernicke's encephalopathy, hepatic encephalopathy, and myxedema.

Coma with hyperthermia is seen in heat stroke, status epilepticus, malignant hyperthermia related to inhalational anesthetics, anticholinergic drug intoxication, pontine

hemorrhage, and certain hypothalamic lesions.

D- Examination of skin

Pallor, Jaundice, Cyanosis, Purpura, Needle marks, Pigmentations…etc.

E- Breathing

1- Pattern : Air hunger

Cheyne- stokes

2- Smell : Drugs

Alcohol

Acetone smell

Fetor hepaticus

F. SIGNS OF MENINGEAL IRRITATION

Signs of meningeal irritation [eg, nuchal rigidity or the Brudzinski sign are of great importance in leading to the prompt diagnosis of

meningitis or subarachnoid hemorrhage, but they are lost in deep coma.

G.PUPIL SIZE : constricted;Pontine hemorrhage Organophosphorous poisioning dilated;Anticholinergic drugs

H. OPTIC FUNDI

Examination of the optic fundi may reveal papilledema or retinal hemorrhages compatible with chronic or acute hypertension or an elevation in intracranial pressure.

Subhyaloid (superficial retinal) hemorrhages in an adult strongly suggest subarachnoid hemorrhage

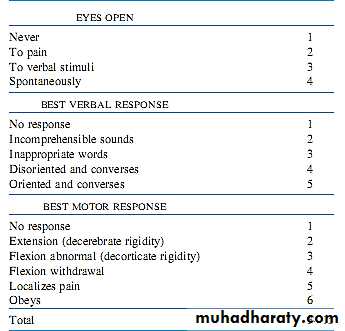

Glasgow Coma Scale