Epilepsy

• Epilepsy is one of the most common and disabling public health problems,

affecting approximately 50 million people around the world.

• The initial diagnostic approach to the patient with epilepsy and related episodic

disorders has importance for both long-term prognosis and treatment, including

the determination of whether treatment is necessary and the type(s) of therapy

to be considered.

• When evaluating a patient with possible epilepsy, the basic approach is as

follows:

1. Is this epilepsy?

2. is it focal or generalized?

3. Is there is any underlying cause or Is it an epileptic syndrome?

• The basic goals of treatment for epilepsy are to help the patient achieve seizure

freedom without adverse effects of therapies, or at least minimize the frequency

of seizures with minimal adverse effects and to maximize quality of life for people

with epilepsy.

• Seizures are sudden but transient behavioral, sensory, motor, or visual symptom

or sign, and caused by abnormal excessive cortical neuronal activity.

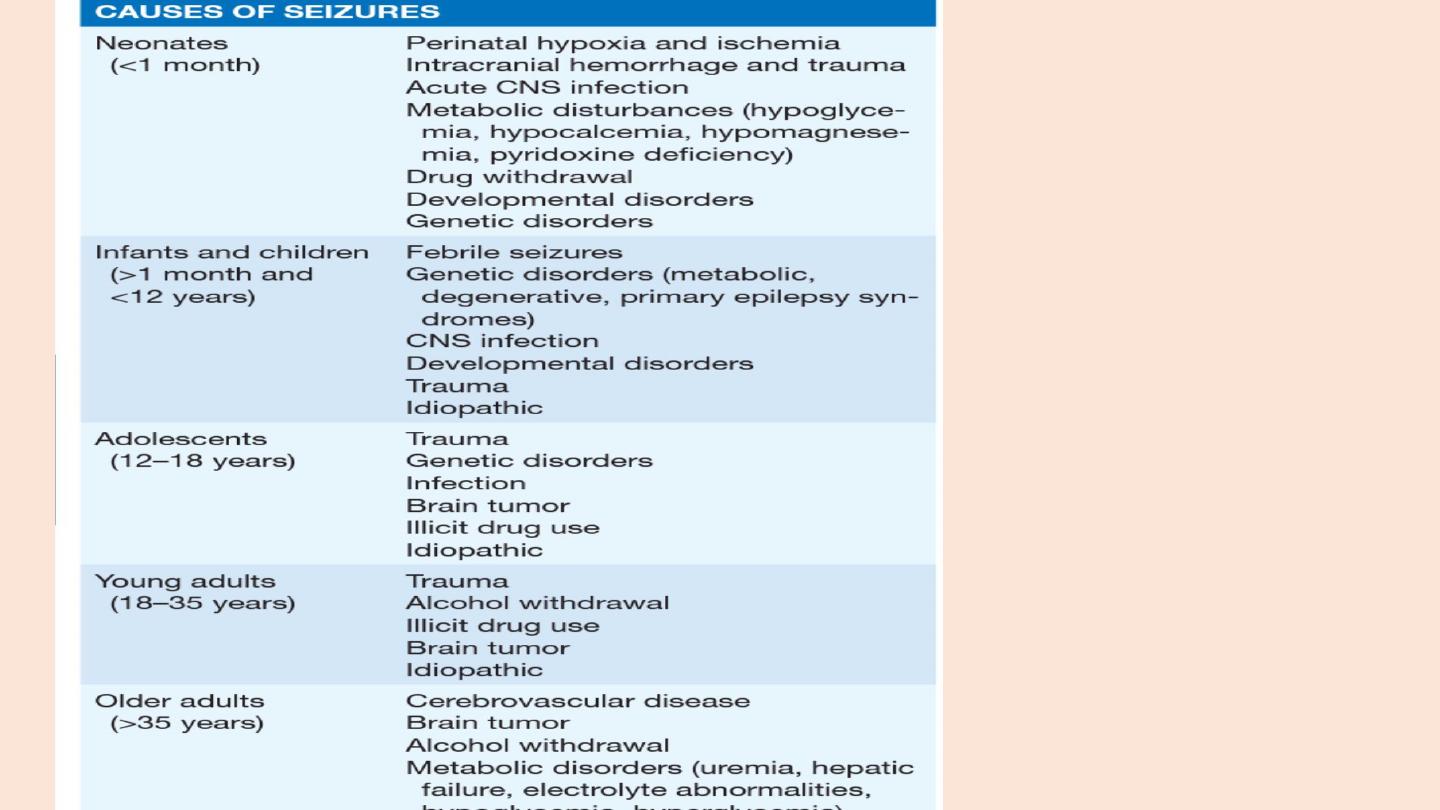

• Seizures may occur spontaneously without provocation or may be provoked by

certain influences (eg, brain trauma, hemorrhage, metabolic disturbance , or drug

exposures).

• In 2014, a new practical definition for epilepsy as a disease with

PRACTICAL DEFINITION OF EPILEPSY

recurrent unprovoked seizures (ie, two or more unprovoked seizures occurring at least 24

hours apart)

• 1-Partial seizures

• a. Simple partial seizures (with motor, sensory, autonomic, or psychic signs)

• b. Complex partial seizures

• c. Partial seizures with secondary generalization

• 2. Primarily generalized seizures

• a. Absence (petit mal)

• b. Tonic-clonic (grand mal)

• c. Tonic d. Atonic

• e. Myoclonic

CLASSIFICATION OF SEIZURES

Partial seizure

• features Focal seizures can cause motor, sensory, autonomic, or psychic

symptoms without impairment of cognition. For example, a patient having a focal

motor seizure arising from the right primary motor cortex near the area

controlling hand movement will note the onset of involuntary movements of the

contralateral, left hand.

• Three additional features of focal motor seizures are worth noting. First, in some

patients the abnormal motor movements may begin in a very restricted region

such as the fingers and gradually progress (over seconds to minutes) to include a

larger portion of the extremit known as a “Jacksonian march,”

• Second, patients may experience a localized paresis (Todd’s paralysis) for minutes

to many hours in the involved region following the seizure.

• Third, in rare instances the seizure may continue for hours or days. This condition,

termed epilepsia partialis continua , is often refractory to medical therapy

Absence seizure

• Typical absence seizures are characterized by sudden, brief lapses of

consciousness without loss of postural control. The seizure typically lasts

for only seconds, consciousness returns as suddenly as it was lost, and

there is no postictal confusion.

• onset usually in childhood (ages 4–8 years) or early adolescence

• The seizures can occur hundreds of times per day, but the child may be

unaware of it.

• it is not surprising that the first clue to absence epilepsy is often

unexplained “daydreaming” and a decline in school performance

recognized by a teacher.

• Best treatment ethosuximide

Generalized, tonic-clonic seizures

• Generalized-onset tonic-clonic seizures are the main seizure type in ∼

10% of all persons with epilepsy. They are also the most common

seizure type resulting from metabolic derangements and are

therefore frequently encountered in many different clinical settings.

The seizure usually begins abruptly without warning,

• There are a number of variants of the generalized tonic-clonic seizure,

including pure tonic and pure clonic seizures

Atonic seizure

• Atonic seizures are characterized by sudden loss of postural muscle

tone lasting 1–2 s. Consciousness is briefly impaired, but there is

usually no postictal confusion.

• A very brief seizure may cause only a quick head drop or nodding

movement, while a longer seizure will cause the patient to collapse.

This can be extremely dangerous, since there is a substantial risk of

direct head injury with the fall.

Myoclonic seizure

• Myoclonus is a sudden and brief muscle contraction that may involve

one part of the body or the entire body

• A normal, common physiologic form of myoclonus is the sudden

jerking movement observed while falling asleep.

• Pathologic myoclonus is most commonly seen in association with

metabolic disorders, degenerative CNS diseases, or anoxic brain injury

Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy

• Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME) is a generalized seizure disorder of unknown

cause that appears in early adolescence and is usually characterized by bilateral

myoclonic jerks that may be single or repetitive.

• The myoclonic seizures are most frequent in the morning after awakening and

can be provoked by sleep deprivation.

• Consciousness is preserved unless the myoclonus is especially severe.

• Many patients also experience generalized tonic-clonic seizures, and up to one-

third have absence seizures.

• Although complete remission is relatively uncommon, the seizures respond well

to appropriate anticonvulsant medication.

• There is often a family history of epilepsy.

• Drug of choice levetiracetam

• A patient with a penetrating head wound, depressed skull fracture,

intracranial hemorrhage, or prolonged posttraumatic coma or

amnesia has a 40–50% risk of developing epilepsy, while a patient

with a closed head injury and cerebral contusion has a 5–25% risk

• Cerebrovascular disease may account for ∼ 50% of new cases of

epilepsy in patients older than age 65.

• Acute seizures (i.e., occurring at the time of the stroke) are seen

more often with embolic rather than hemorrhagic or thrombotic

stroke.

• Chronic seizures typically appear months to years after the initial

event and are associated with all forms of stroke.

HISTORY AND EXAMINATION

• The first goal is to determine whether the event was truly a seizure.

• An in-depth history is essential

• in many cases the diagnosis of a seizure is based solely on clinical

grounds—the examination and laboratory studies are often normal .

• Questions should focus on the symptoms before, during, and after the

episode in order to differentiate a seizure from other paroxysmal events

• witnesses to the event should be interviewed carefully.

• The history should also focus on risk factors and predisposing events

include a history of febrile seizures, earlier auras or brief seizures not

recognized as such, and a family history of seizures

• Epileptogenic factors such as prior head trauma, stroke, tumor, or infection

of the nervous system should be identified.

• All patients who have a possible seizure disorder should be evaluated

with an EEG as soon as possible

• The absence of electrographic seizure activity does not exclude a

seizure

• video-EEG telemetry is now a routine approach for the accurate

diagnosis of epilepsy in patients with poorly characterized events or

seizures that are difficult to control.

• BRAIN IMAGING Almost all patients with new-onset seizures should

have a brain imaging study to determine whether there is an

underlying structural abnormality that is responsible.

How to administer first aid for seizures

• Move person away from danger (fire, water, machinery, furniture).

• After convulsions cease, turn person into ‘recovery’ position (semi-

prone).

• Ensure airway is clear but do NOT insert anything in mouth (tongue-

biting occurs at seizure onset and cannot be prevented by observers).

• If convulsions continue for more than 5 mins or recur without person

regaining consciousness, summon urgent medical attention.

• Do not leave person alone until fully recovered (drowsiness and

confusion can persist for up to 1 hr)

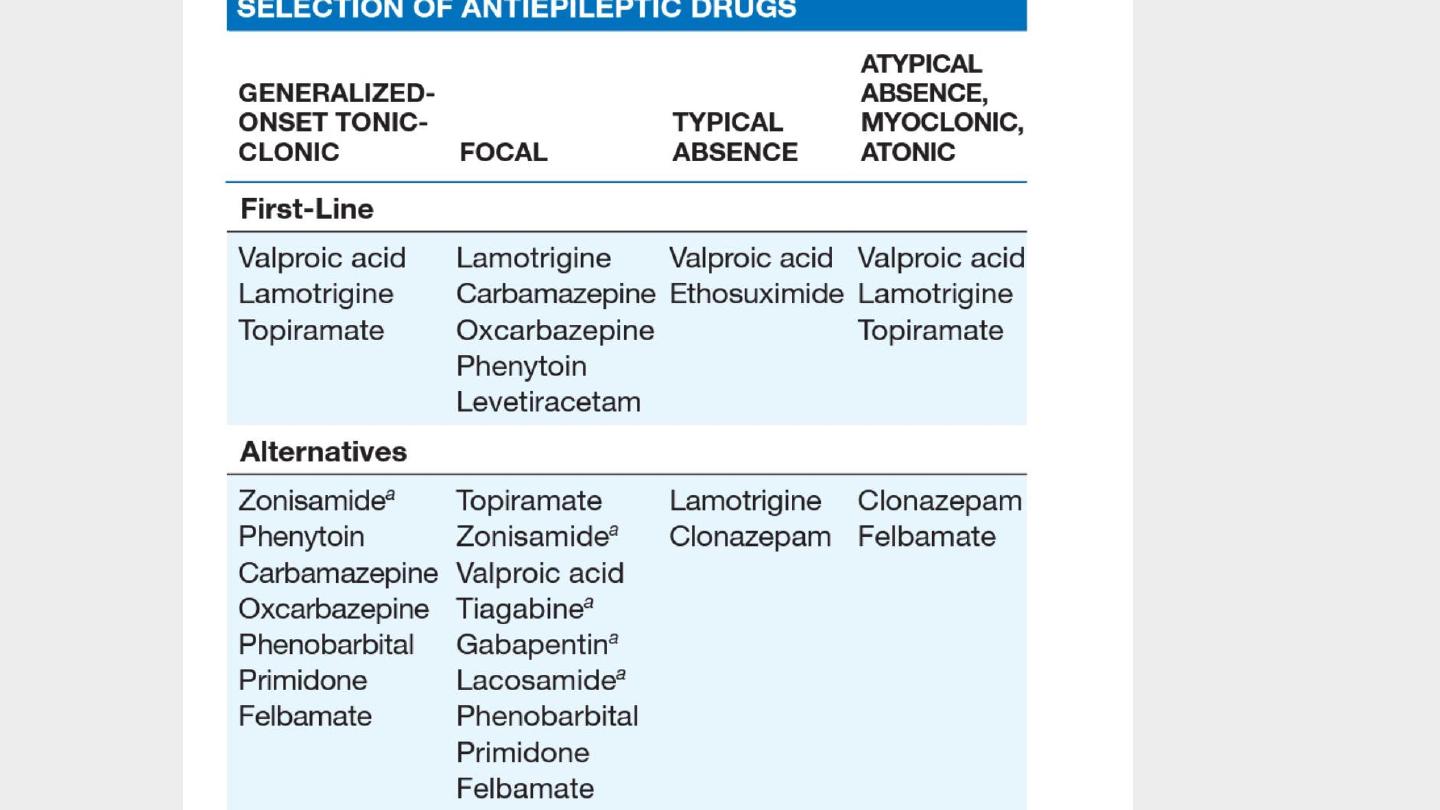

Anticonvulsant therapy

• Anticonvulsant drug treatment (anti-epileptic drugs, or AEDs) should

be considered after more than one unpro voked seizure.

• The decision to start treatment should be shared with the patient, to

enhance compliance.

• A wide range of drugs is available.

• These agents either increase inhibitory neurotransmission in the

brain or alter neuronal sodium channels to prevent abnormally rapid

trans- mission of impulses.

• In the majority of patients, full control is achieved with a single drug

STATUS EPILEPTICUS

• Status epilepticus refers to continuous seizures or repetitive, discrete

seizures with impaired consciousness in the interictal period

• The duration of seizure activity suff icient to meet the definition of

status epilepticus has traditionally been specified as 15–30 min.

• GCSE is an emergency and must be treated immediately , since

cardiorespiratory dysfunction, hyperthermia, and metabolic

derangements can develop as a consequence of prolonged seizures,

and these can lead to irreversible neuronal injury

Potential causes of status epilepticus

• Anoxic-Ischemic Injury

• Autoimmune mediated antibodies

• Brain Tumor /Metastatic /Primary

• CNS Infection Abscess/empyema/ Meningitis /Viral encephalitis

• Congenital/Hereditary

• Drug or Alcohol Intoxication /Withdrawal

• Low Antiepileptic Drug Levels or Change in Antiepileptic Drug Regimen

• Metabolic Disturbance Acidosis Electrolyte imbalance Hypoglycemia or

hyperglycemia Organ failure

• Unknown (Cryptogenic)

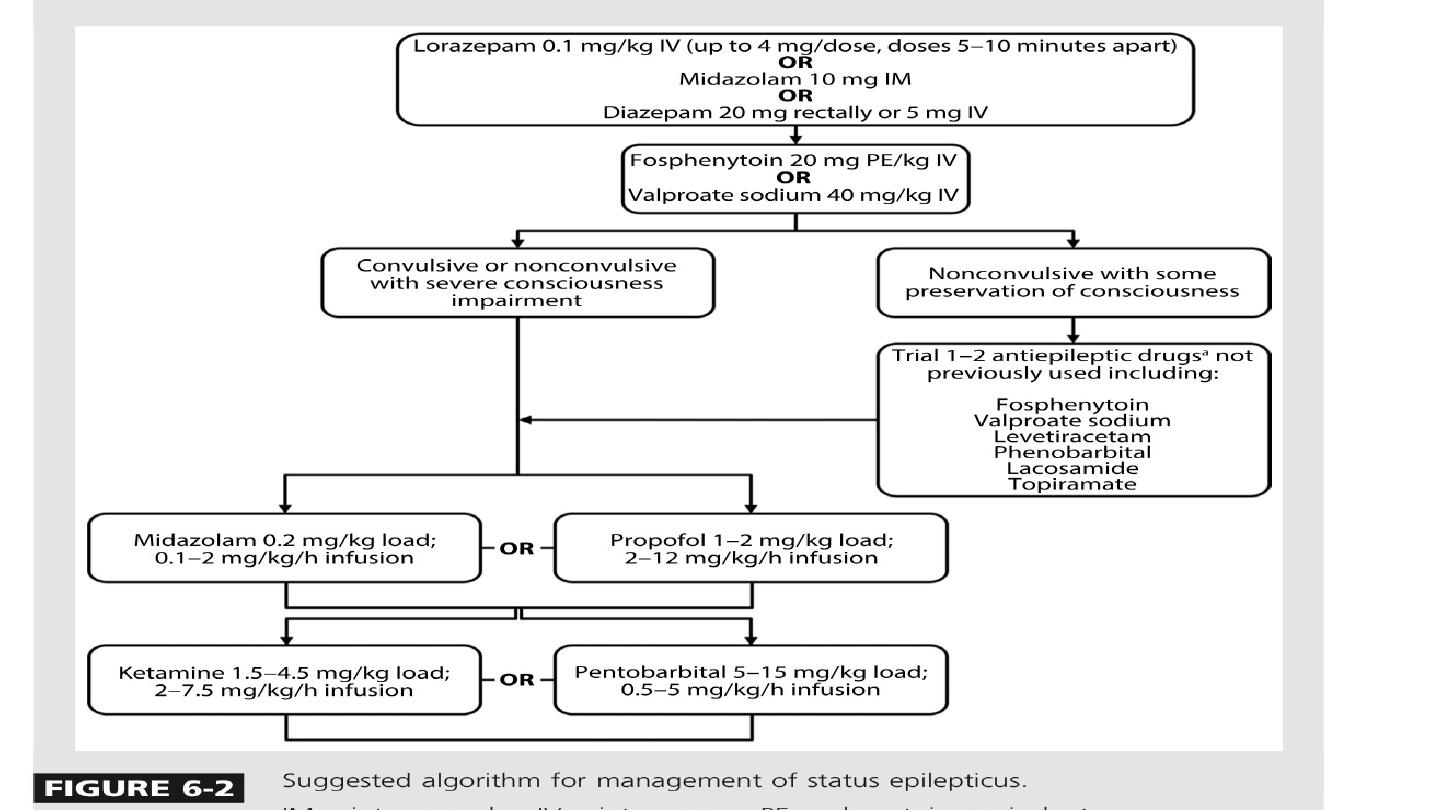

Management of status epilepticus

• Ensure airway is patent; give oxygen to prevent cerebral hypoxia

• Check pulse, blood pressure, and respiratory rate.

• Secure intravenous access.

• Send blood for:Glucose, urea and electrolytes, calcium and magnesium, liver

function, anti-epileptic drug levelsFull blood count and clotting screenStoring a

sample for future analysis (e.g. drug misuse).

• If seizures continue for > 5 mins: give diazepam 10 mg IV (or rectally) or

lorazepam 4 mg IV; repeat once only after 5 to 10 mins.

• Correct any metabolic trigger, e.g. hypoglycaemia

• If seizures continue after 30 mins

• IV infusion (with cardiac monitoring) with one of:

• Phenytoin: 15 mg/kg at 50 mg/min iv

• Fosphenytoin: 15 mg/kg at 100 mg/min iv

• Valoproate sodium: 40 mg/kg iv

• Cardiac monitor and pulse oximetry ,Monitor neurological condition, blood

pressure, respiration; check blood gases

• If seizures still continue after 30–60 mins Transfer to intensive care Start

treatment for refractory status with intubation, ventilation and general

anaesthesia using propofol or thiopentalEEG monitorOnce status controlled

• Commence longer-term anticonvulsant medication with one of:

• Sodium valproate 10 mg/kg IV over 3–5 mins, then 800–2000 mg/day

• Phenytoin: give loading dose (if not already used as above) of 15 mg/kg, infuse at

< 50 mg/min, then 300 mg/dayCarbamazepine 400 mg by nasogastric tube, then

400–1200 mg/day.

• Investigate cause