1

HEART FAILURE

DEFINITION

•

Heart failure describes the clinical syndrome that develops when the

heart cannot maintain adequate output, or can do so only at the

expense of elevated ventricular flling pressure.

•

In mild to moderate forms of heart failure, cardiac output is normal at

rest and only becomes impaired when the metabolic demand

increases during exercise or some other form of stress.

•

In practice, heart failure may be diagnosed when a patient with

signifcant heart disease develops the signs or symptoms of a low

cardiac output, pulmonary congestion or systemic venous congestion.

Almost all forms of heart disease can lead to heart failure. An accurate

aetiological diagnosis is important because treatment of the

underlying cause may reverse heart failure or prevent its progression

2

Types of heart failure

Left, right and biventricular heart failure

The left side of the heart comprises the functional unit of the LA and

LV, together with the mitral and aortic

valves; the right heart comprises the RA, RV, and tricuspid and

pulmonary valves.

•

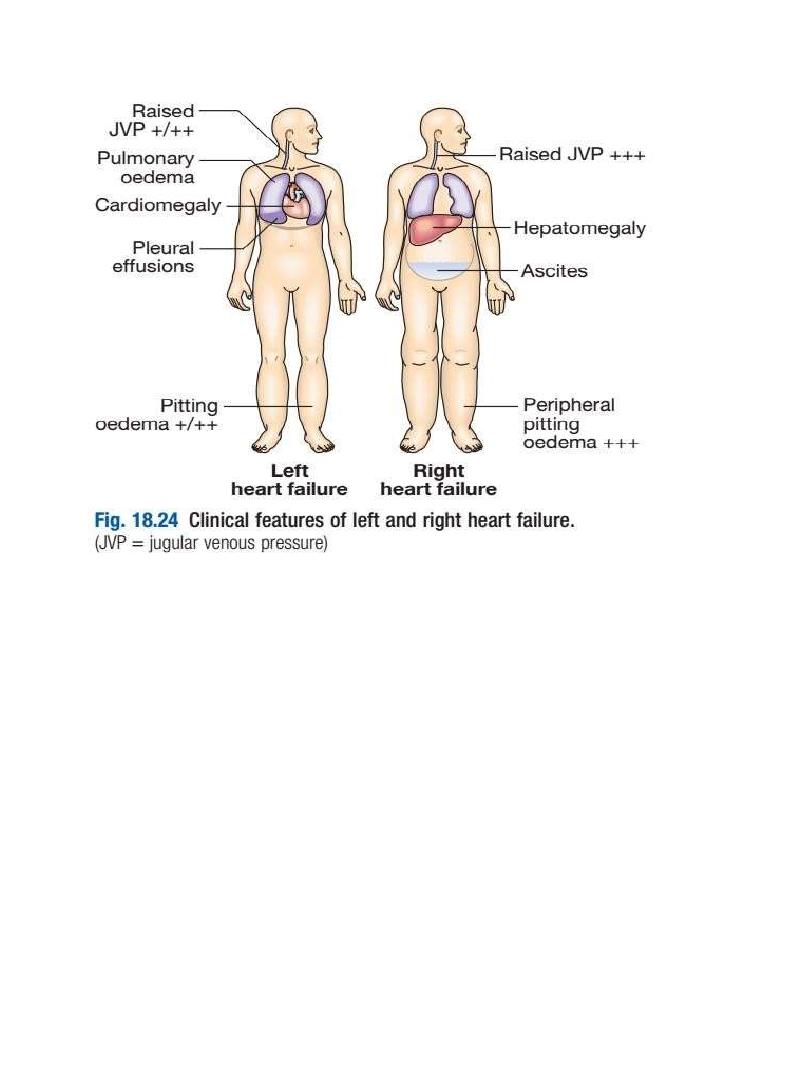

Left-sided heart failure :

There is a reduction in left ventricular output and an increase in left

atrial and pulmonary venous pressure. An acute increase in left atrial

pressure causes pulmonary congestion or pulmonary oedema; a more

gradual increase in left atrial pressure, as occurs with mitral stenosis,

leads to reflex pulmonary vasoconstriction, which protects the patient

from pulmonary oedema. This increases pulmonary vascular resistance

and causes pulmonary hypertension, which can, in turn, impair right

ventricular function.

•

Right-sided heart failure

There is a reduction in right ventricular output and an increase in right

atrial and systemic venous pressure. Causes of isolated

right heart failure include chronic lung disease (cor pulmonale),

pulmonary embolism and pulmonary valvular stenosis.

• Biventricular heart failure

Failure of the left and right heart may develop because the disease

process, such as dilated cardiomyopathy or ischaemic heart disease,

affects both ventricles or because disease of

the left heart leads to chronic elevation of the left atrial pressure,

pulmonary hypertension and right heart failure.

Diastolic and systolic dysfunction

Heart failure may develop as a result of impaired myocardial

contraction (systolic dysfunction) but can also be due to poor

ventricular flling and high flling pressures stemming from abnormal

3

ventricular relaxation (diastolic dysfunction). The latter is caused by a

stiff, noncompliant ventricle and is commonly found in patients with

left ventricular hypertrophy. Systolic and diastolic

dysfunction often coexist, particularly in patients with coronary artery

disease.

High-output failure

A large arteriovenous shunt, beri-beri , severe anaemia or

thyrotoxicosis can occasionally cause heart failure due to an

excessively high cardiac output.

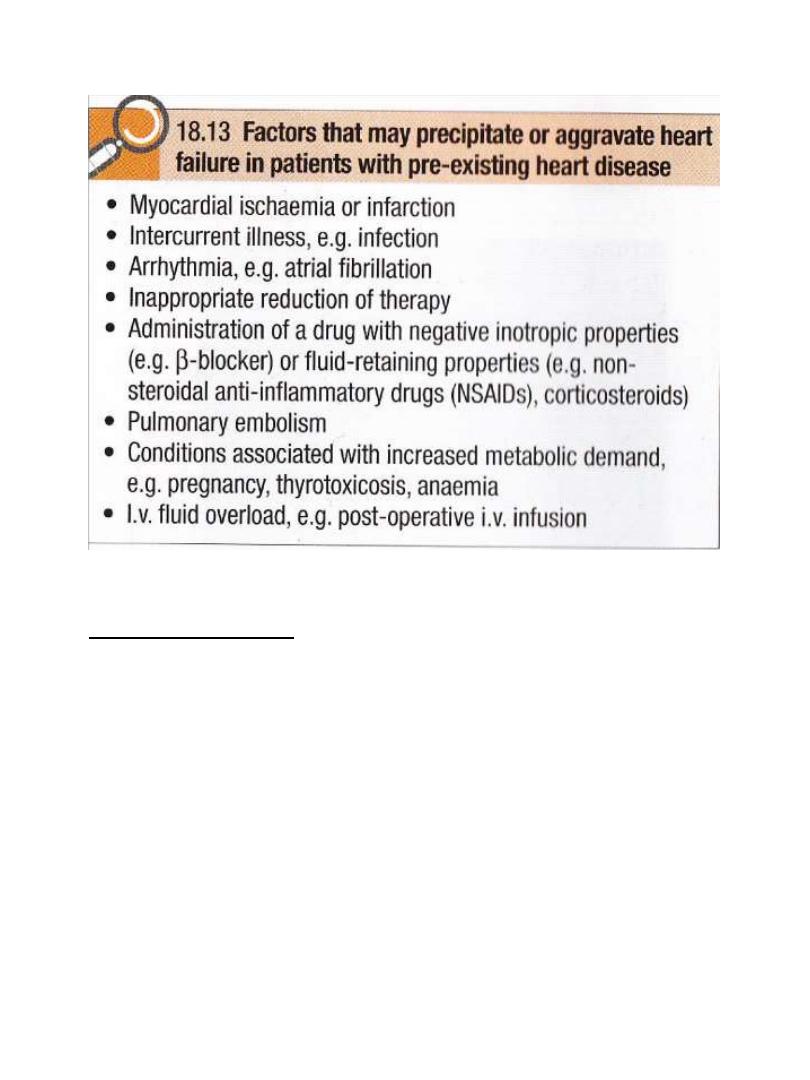

Acute and chronic heart failure

Heart failure may develop suddenly, as in MI, or gradually, as in

progressive valvular heart disease. When there is gradual impairment

of cardiac function, several compensatory changes may take place.

The term ‘compensated heart failure’ is sometimes used to describe

the condition of those with impaired cardiac function, in whom

adaptive changes have prevented the development of

overt heart failure. A minor event, such as an intercurrent infection or

development of atrial fbrillation, may precipitate overt or acute heart

failure . Acute left heart failure occurs, either de novo or as an acute

decompensated episode, on a background of chronic heart failure: so-

called acute-onchronic heart failure.

4

Clinical Assessment

• Acute left heart failure

Acute de novo left ventricular failure presents with a sudden onset of

dyspnoea at rest that rapidly progresses to acute respiratory distress,

orthopnoea and prostration. The precipitant, such as acute MI, is often

apparent from the history.

The patient appears agitated, pale and clammy. The peripheries are

cool to the touch and the pulse is rapid.

Inappropriate bradycardia or excessive tachycardia should be identifed

promptly, as this may be the precipitant for the acute episode of heart

failure. The BP is usually high because of sympathetic nervous system

activation, but may be normal or low if the patient is in cardiogenic

shock The jugular venous pressure (JVP) is usually elevated,

particularly with associated fluid overload or right heart failure. In

acute de novo heart failure, there has been no time for ventricular

5

dilatation and the apex is not displaced. A ‘gallop’ rhythm, with a third

heart sound, is heard quite early in the development of acute leftsided

heart failure. A new systolic murmur may signify acute mitral

regurgitation or ventricular septa rupture. Auscultatory fndings in

pulmonary oedema are fine basal end-inspiratory crepitations at the

lung bases, or throughout the lungs if pulmonary oedema is severe.

Expiratory wheeze often accompanies this.

Acute-on-chronic heart failure will have additional features of long-

standing heart failure. Potential precipitants, such as an upper

respiratory tract infection or inappropriate cessation of diuretic

medication, should be identifed.

• Chronic heart failure

Patients with chronic heart failure commonly follow a relapsing and

remitting course, with periods of stability and episodes of

decompensation, leading to worsening symptoms that may

necessitate hospitalisation. The clinical picture depends on the nature

of the underlying heart disease, the type of heart failure that it has

evoked, and the neurohumoral changes that have developed

Low cardiac output causes fatigue, listlessness and a poor effort

tolerance; the peripheries are cold and the BP is low. To maintain

perfusion of vital organs, blood flow is diverted away from skeletal

muscle and this may contribute to fatigue and weakness. Poor renal

perfusion leads to oliguria and uraemia.

Pulmonary oedema due to left heart failure presents as above and

with inspiratory crepitations over the lung bases. In contrast, right

heart failure produces a high JVP with hepatic congestion and

dependent peripheral oedema. In ambulant patients, the oedema

affects the ankles, whereas, in bed-bound patients, it collects around

the thighs and sacrum. Ascites or pleural effusion may occur .

Chronic heart failure is sometimes associated with marked weight loss

(cardiac cachexia), caused by a combination of anorexia and impaired

absorption due to gastrointestinal congestion, poor tissue perfusion

due to a low cardiac output, and skeletal muscle atrophy due to

immobility.

6

Investigations

1. Blood gas analysis

2. Renal function test

3. Hb & PCV

4. Thyroid function test

5. ECG

6. BNP (brain natriuretic peptide)

7. Echocardiography

8. Chest X ray

7

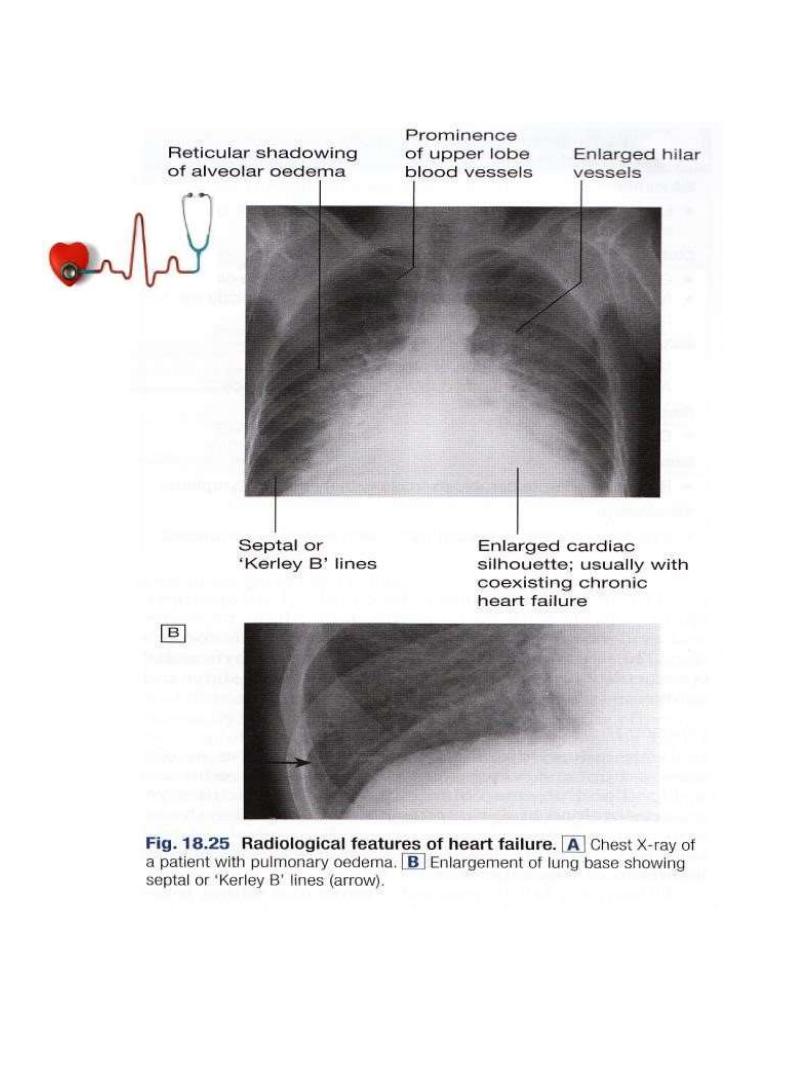

Chest X ray

High pulmonary venous pressure in left-sided heart failure frst shows

on the chest X-ray as an abnormal distension of the upper lobe

pulmonary veins (with the patient in the erect position). The

vascularity of the lung felds becomes more prominent, and the right

and left pulmonary arteries dilate. Subsequently, interstitial oedema

causes thickened interlobular septa and dilated lymphatics. These are

evident as horizontal lines in the costophrenic angles (septal or ‘Kerley

B’ lines). More advanced changes due to alveolar oedema cause a hazy

opacifcation spreading from the hilar regions, and pleural effusions

X ray findings in heart failure

•

Chronologically…

•

In CXR..

•

Hilar opacities

•

Bat wing or butterfly appearance

•

Prominent upper lobe vessels

•

Kerley B lines

•

Encysted fissural edema (vanishing tumor) which is accumulation of

fluid in the fissural space between 2 lobes, giving in x-ray an opacity

that look like a tumor ,which however, resolve by diuretics

•

Later… cardiomegaly,,, and in advanced heart failure,there may be

pleural effusion

8

9

Mx of Acute Pulmonary Edema

This is an acute medical emergency:

•

Sit the patient up to reduce pulmonary congestion, with complete bed

rest.

•

Give oxygen (high-flow, high-concentration).

Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (continuous positive airways

pressure (CPAP) of 5–10 mmHg) by a tight-ftting facemask results in a

more rapid clinical improvement.

•

Administer nitrates, such as IV glyceryl trinitrate (10–200 µg/min or

buccal glyceryl trinitrate 2–5 mg, titrated upwards every 10 minutes),

until clinical improvement occurs or systolic BP falls to less than 110

mmHg.

•

Administer a loop diuretic, such as furosemide (50–100 mg IV).

The patient should initially be kept rested, with continuous monitoring

of cardiac rhythm, BP and pulse oximetry. Intravenous opiates, like

morphin 5-10mg must be used sparingly in

distressed patients, as they may cause respiratory depression and

exacerbation of hypoxaemia and hypercapnia.

If these measures prove ineffective, inotropic agents(Dobutamine)

may be required to augment cardiac output, particularly in

hypotensive patients. Insertion of an intra-aortic balloon pump may be

benefcial in patients with acute cardiogenic pulmonary oedema and

shock.

Rotating tourniquet to reduce preload

Hemofiltration is among last choices in unresponsive cases

Mechanical ventilation in unresponsive hypoxia, hypercapnia,

disturbed level of consciousness with low spO2

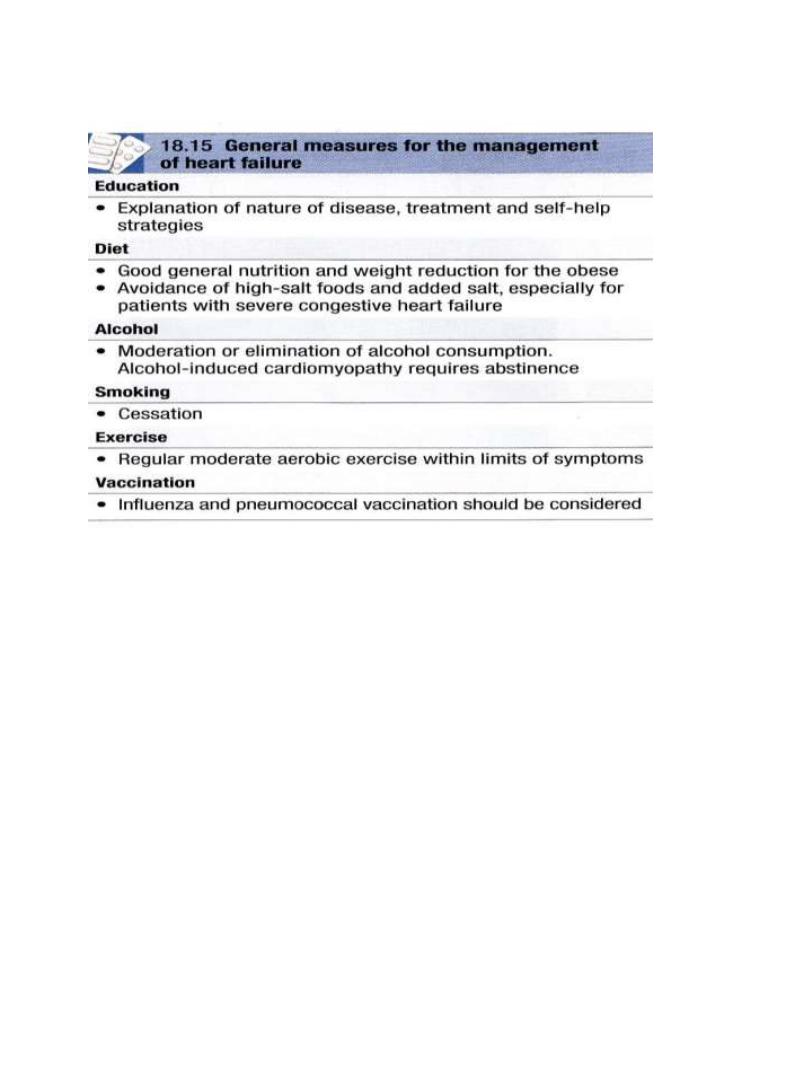

Management of chronic heart failure

•

General measures

•

Drug therapy

10

General measures

Drug therapy

•

Diuretic therapy (FUROSEMIDE & SPIRONOLACTONE)

•

Vasodilator therapy (Venodilator..nitrates ,,arteriodilator..hydralazine)

•

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibition therapy.

•

Angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) therapy.

•

Beta-adrenoceptor blocker therapy, small dose ..ex Bisoprolol

•

Digoxin (HF with AF only..)

•

Amiodarone (chemical cardioverter)

•

Ivabradine

•

For details,, see DAVIDSON P.551, 552, 553

11

Drugs that improve prognosis in heart failure

•

B- blockers

•

Spironolactone

•

ACE inhibitors

•

Nitrates

•

Angiotensin neprilysin inhibitor

Non pharmacological Options

•

IMPLANTABLE CARDIAC DEFIBRILLATOR

•

CORONARY REVASCULARISATION

•

CARDIAC RESYNCRONIZATION THERAPY

•

VENTRICULAR ASSIST DEVICE

•

CARDIAC TRANSPLANTATION

•

CARDIOPULMONARY TRANSPLANTATION