Hypertension

Presented by:

Leena Mehjin

Yasir Emad

Shahad Mikdad

Rahma Jamal

Supervised by:

Dr. Muhamad Abdulhadi

Definition:

Blood pressure is the force exerted by the blood against

the walls of the blood vessels. The pressure depends on

the work being done by the heart and the resistance of

the blood vessels

.

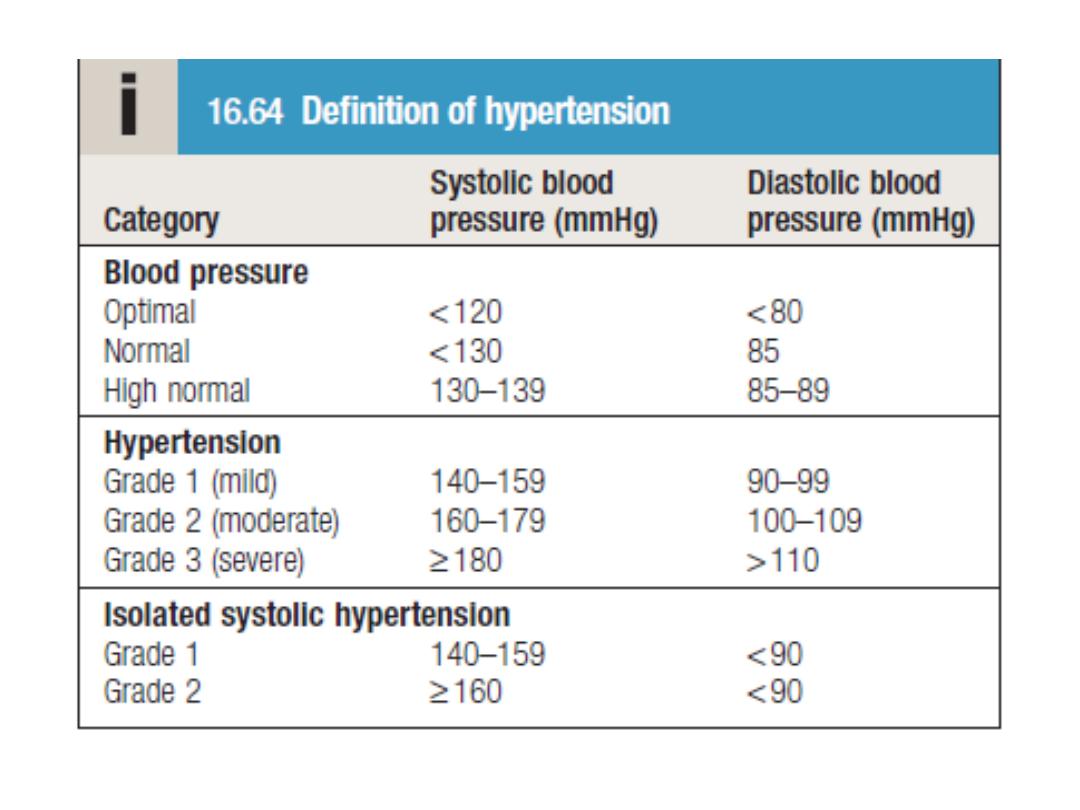

Medical guidelines define hypertension as a blood

pressure higher than 130 over 80 millimeters of

mercury (mmHg), according to guidelines issued by the

American Heart Association (AHA) in November 2017.

Epidemiology:

Hypertension is an epidemic affecting one billion people and is

the commonest risk factor for death throughout the world.

World health statistics 2012 has estimated the prevalence of

hypertension to be 29.2% in males and 24.8% in females.

Approximately 90 percent for men and women who are non

hypertensive at 55 or 65 years will develop hypertension by the

age of 80–85. Hypertension is not limited to rich population and

affects countries across all income groups. Out of total 58.8

million deaths worldwide in year 2004, high blood pressure was

responsible for 12.8% (7.5 million deaths). World over

hypertension is responsible for 51% of cerebrovascular disease

and 45% of ischemic heart disease deaths. Unlike the popular

belief that hypertension is more important for high-income

countries, people in low- and middle-income countries have

more than double the risk of dying of hypertension.

Types of Hypertension

There are two primary types of hypertension. For 95 percent

of people with high blood pressure, the cause of their

hypertension is unknown — this is called essential, or

primary, hypertension. When a cause can be found, the

condition is called secondary hypertension.

Essential hypertension. This type of hypertension is

diagnosed after a doctor notices that your blood pressure is

high on three or more visits and eliminates all other causes of

hypertension. Usually people with essential hypertension

have no symptoms, but you may experience frequent

headaches, tiredness, dizziness, or nose bleeds. Although the

cause is unknown, researchers do know that obesity,

smoking, alcohol, diet, and heredity all play a role in essential

hypertension.

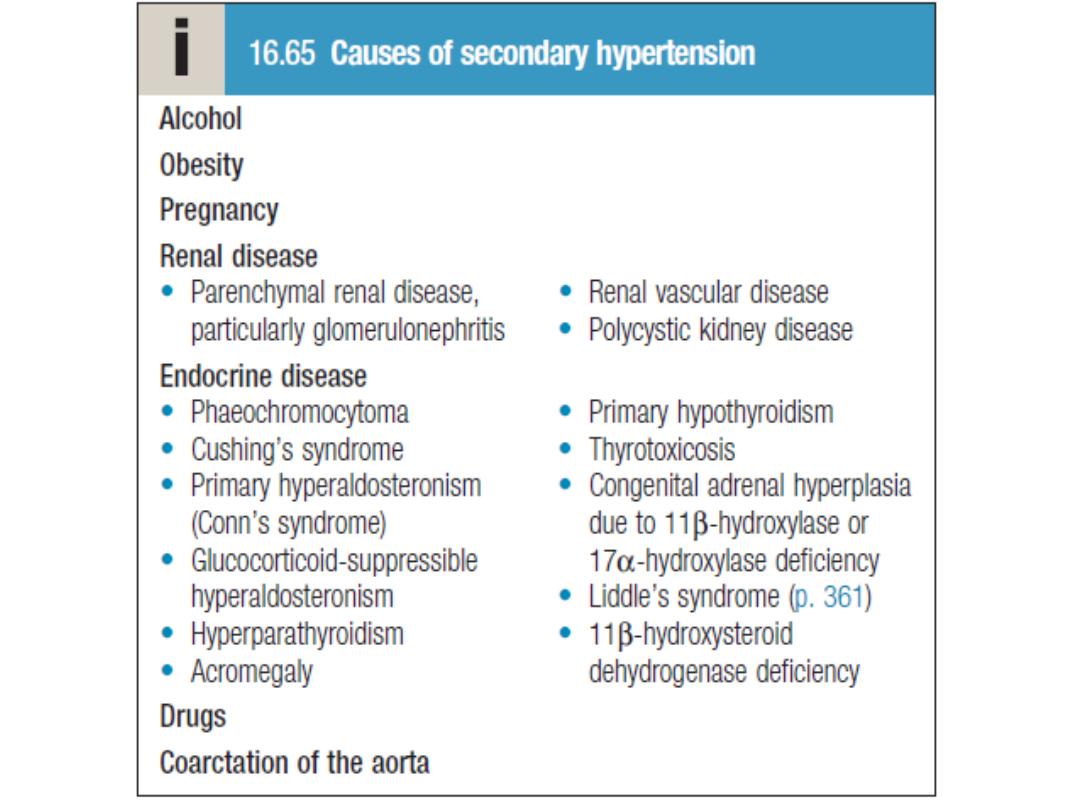

Secondary hypertension.

The most common cause of secondary hypertension is

an abnormality in the arteries supplying blood to the

kidneys airway obstruction during sleep

diseases and tumors of the adrenal glands,

hormone abnormalities

thyroid disease

too much salt or alcohol in the diet

Drugs can cause secondary hypertension, including

over-the-counter medications such as ibuprofen

(Motrin, Advil, and others) and pseudoephedrine

(Afrin, Sudafed, and others)

if the cause is found, hypertension can often be

controlled

Additional Types of Hypertension

Isolated systolic hypertension, malignant hypertension,

and resistant hypertension are all recognized

hypertension types with specific diagnostic criteria.

Isolated systolic hypertension Normal blood pressure

is considered under 120/80. With isolated systolic

hypertension, the systolic pressure rises above 140,

while the lower number stays near the normal range,

below 90. This type of hypertension is most common in

people over the age of 65 and is caused by the loss of

elasticity in the arteries. The systolic pressure is much

more important than the diastolic pressure when it

comes to the risk of cardiovascular disease for an older

person.

Malignant hypertension. This hypertension type

occurs in only about 1 percent of people with

hypertension. It is more common in younger

adults, African-American men, and women who

have pregnancy toxemia. Malignant

hypertension occurs when your blood pressure

rises extremely quickly. If your diastolic pressure

goes over 130, you may have malignant

hypertension. This is a medical emergency and

should be treated in a hospital. Symptoms

include numbness in the arms and legs, blurred

vision, confusion, chest pain, and headache.

It is characterised by accelerated microvascular

damage with necrosis in the walls of small

arteries and arterioles (fibrinoid necrosis) and by

intravascular thrombosis.

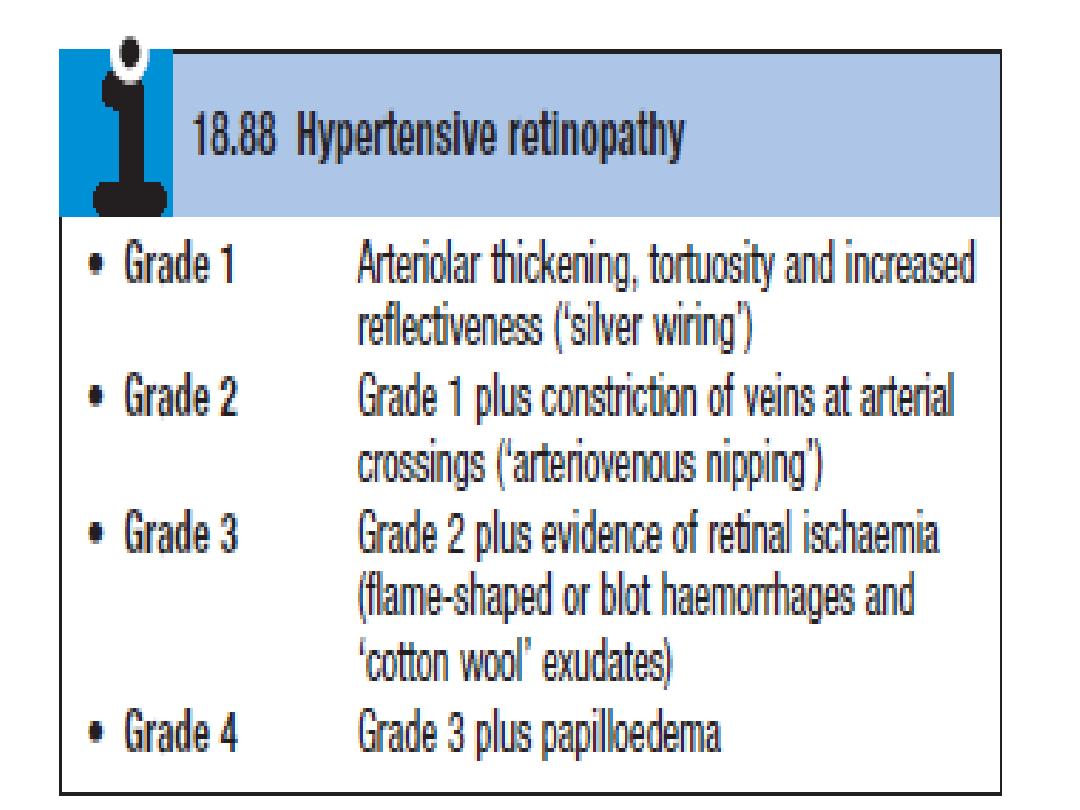

The diagnosis is based on evidence of high BP

and rapidly progressive end-organ damage, such

as retinopathy (grade 3 or 4), renal dysfunction

(especially proteinuria) and/or hypertensive

encephalopathy. Left ventricular failure may

occur and, if this is untreated, death occurs

within months

.

Resistant hypertension. If your doctor has prescribed three

different types of antihypertensive medications and your blood

pressure is still too high, you have resistant hypertension.

Resistant hypertension may occur in 20 to 30 percent of high

blood pressure cases. Resistant hypertension may have a genetic

component and is more common in people who are old, obese,

female, African American

Although this may be due to genuine resistance to therapy in

some cases, a more common cause of treatment failure is non-

adherence to drug therapy.

Resistant hypertension can also be caused by

failure to recognise an underlying cause, such as renal artery

stenosis or phaeochromocytoma

Pathogenesis

Many factors may contribute to the regulation of BP and the development of

hypertension, including:

renal dysfunction

peripheral resistance

vessel tone

endothelial dysfunction,

autonomic tone

insulin resistance

neurohumoral factors

Hypertension is more common in some

ethnic groups, particularly African Americans and Japanese, and

approximately 40–60% is explained by genetic factors. Age is a

strong risk factor in all ethnic groups. Important environmental

factors include a high salt intake, heavy consumption of alcohol,

obesity and lack of exercise. Impaired intrauterine growth and low

birth weight are associated with an increased risk of hypertension

later in life.

Clinical features

Hypertension is usually asymptomatic until the

diagnosis is made

at a routine physical examination or when a

complication arises.

Reflecting this fact, a BP check is advisable every 5

years in adults

over 40 years of age to pick up occult hypertension.

Sometimes

clinical features may be observed that can give a

clue to the

underlying cause of hypertension.

•

These include radio-femoral

•

delay in patients with coarctation of the aorta (see Fig. 16.93,

•

p. 534), enlarged kidneys in patients with polycystic kidney

•

disease (p. 405), abdominal bruits that may suggest renal

artery

•

stenosis (p. 406), and the characteristic facies and habitus of

•

Cushing’s syndrome (Box 16.65). Examination may also reveal

•

evidence of risk factors for hypertension, such as central

obesity

•

and hyperlipidaemia. Other signs may be observed that are

due

•

to the complications of hypertension. These include signs of

left

•

ventricular hypertrophy, accentuation of the aortic component

•

of the second heart sound, and a fourth heart sound. AF is

•

common and may be due to diastolic dysfunction caused by

•

left ventricular hypertrophy or the effects of CAD.

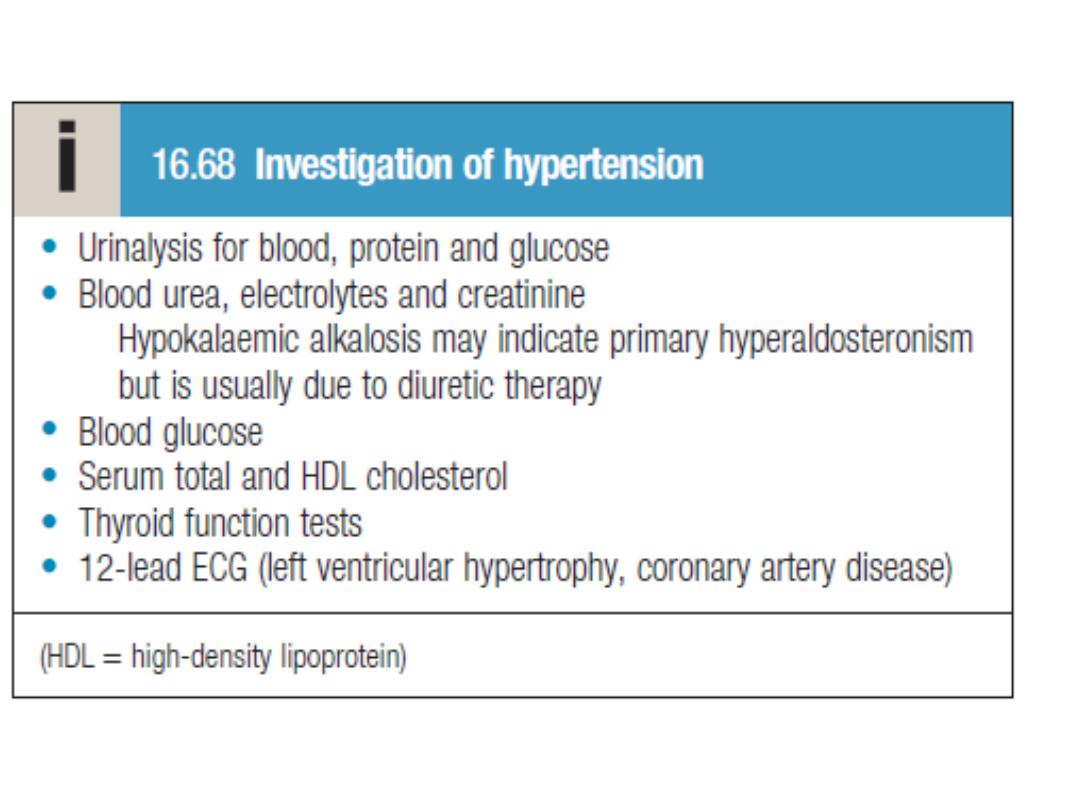

Investigations

•

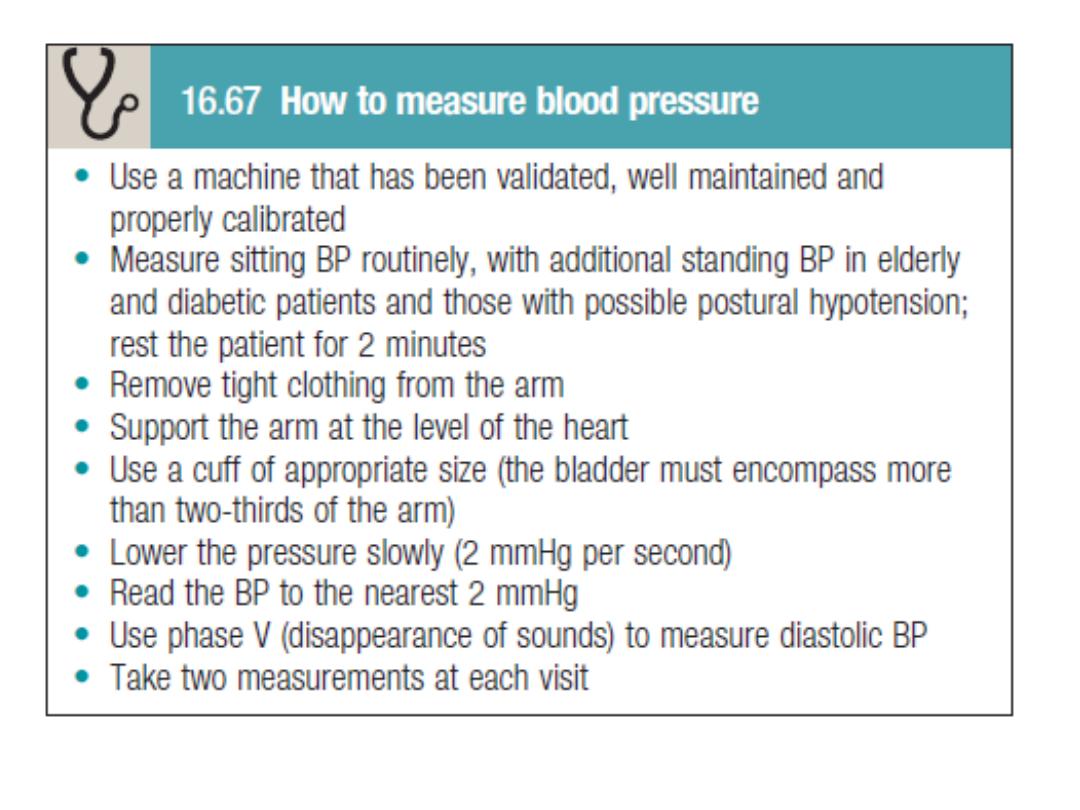

A decision to embark on antihypertensive therapy effectively

•

commits the patient to life-long treatment, so readings must

be

•

as accurate as possible. The objectives are to:

•

• confirm the diagnosis by obtaining accurate, representative

•

BP measurements

•

• identify contributory factors and any underlying causes

•

• assess other risk factors and quantify cardiovascular risk

•

• detect any complications that are already present

•

• identify comorbidity that may influence the choice of

•

antihypertensive therapy.

Target organ damage

The adverse effects of hypertension on the organs .

Blood vessels

In larger arteries (> 1 mm in diameter), the internal

elastic lamina is thickened, smooth muscle is hypertrophied and fibrous

tissue is deposited. The vessels dilate and become tortuous, and their

walls become less compliant In smaller arteries (< 1 mm), hyaline

arteriosclerosis

occurs in the wall, the lumen narrows and aneurysms may

develop. Widespread atheroma develops

and may lead to coronary and cerebrovascular disease,

particularly if other risk factors (e.g. smoking,

hyperlipidaemia, diabetes) are present.

These structural changes in the vasculature often

perpetuate and aggravate hypertension by increasing

peripheral

vascular resistance and reducing renal blood flow, thereby activating the

renin–angiotensin–aldosterone axis. Hypertension is a major risk factor

in the pathogenesis of aortic aneurysm and aortic dissection.

Central nervous system

Stroke is a common complication of

hypertension and may be due to cerebral haemorrhage or

infarction. Carotid atheroma and TIAs are more common

in hypertensive patients. Subarachnoid haemorrhage is

also associated with hypertension.

Hypertensive encephalopathy is a rare

condition characterised by high BP and neurological

symptoms, including transient disturbances of speech or

vision, paraesthesiae, disorientation, fits and loss of

consciousness. Papilloedema is common. A CT scan of the

brain often shows haemorrhage in and around the basal

ganglia; however, the neurological deficit is usually

reversible if the hypertension is properly controlled.

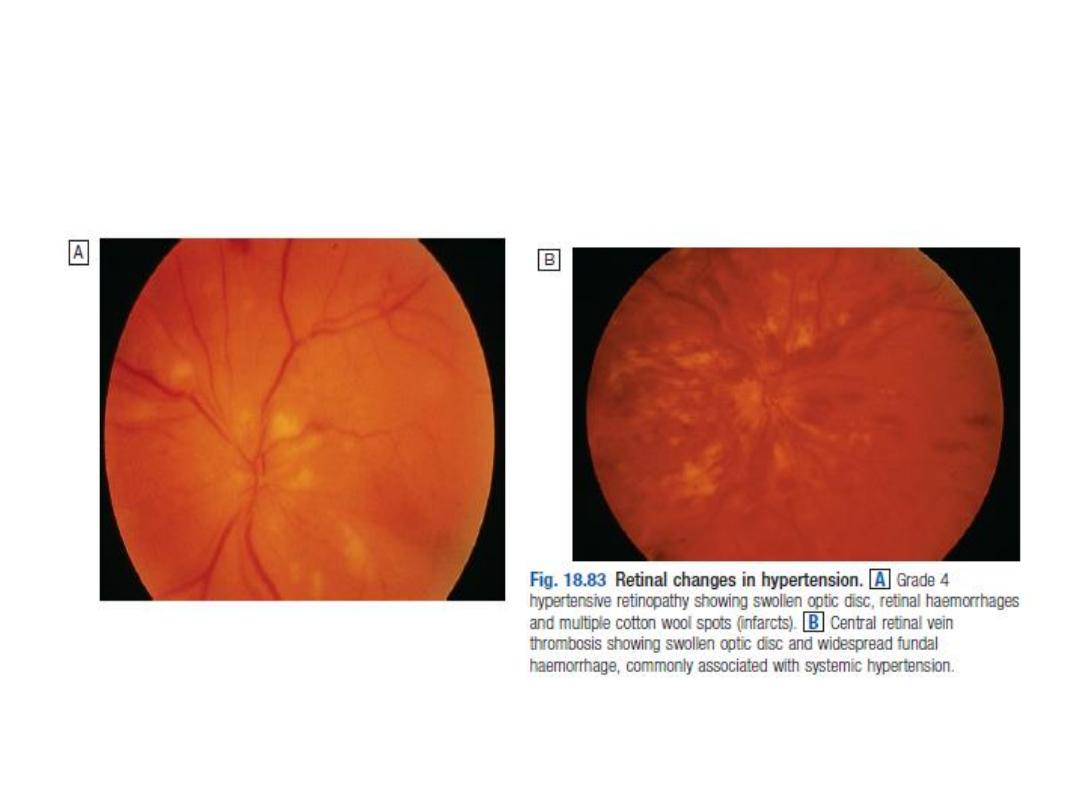

Retina

The optic fundi reveal a gradation of

changes linked to the severity of hypertension;

fundoscopy can, therefore, provide an indication of the

arteriolar damage occurring

Elsewhere.

‘Cotton wool’ exudates are associated with

retinal

ischaemia or infarction, and fade in a few weeks.

‘Hard’ exudates (small, white, dense

deposits of lipid) and microaneurysms (‘dot’

haemorrhages) are more characteristic of diabetic

retinopathy.

Hypertension is also associated with

central retinal vein thrombosis.

Heart

The excess cardiac mortality and morbidity

associated with hypertension are largely due to a higher incidence

of coronary artery disease. High BP places a pressure load on the

heart and may lead to left ventricular hypertrophy with a forceful

apex beat and fourth heart sound.

ECG or echocardiographic evidence of left

ventricular hypertrophy is highly predictive of cardiovascular

complications and therefore particularly useful in risk assessment.

Atrial fibrillation is common and may be due to

diastolic dysfunction caused by left ventricular hypertrophy or the

effects of coronary artery disease.

Severe hypertension can cause left ventricular

failure in the absence of coronary artery disease, particularly

when renal function, and therefore sodium excretion, are

impaired.

Kidneys

Long-standing hypertension

may cause proteinuria and progressive

renal failure by damaging the renal

vasculature.

Management

The objective of

antihypertensive

therapy is to reduce the incidence of adverse

cardiovascular events, particularly CAD,

stroke and heart failure.

Randomised controlled trials have

demonstrated that antihypertensive therapy can

reduce the incidence of stroke and, to a lesser

extent, CAD. The relative benefits (approximately

30% reduction in risk of stroke and 20% reduction

in risk of CAD) are similar in all patient groups, so

the absolute benefit of treatment (total number of

events prevented) is greatest in those at highest

risk.

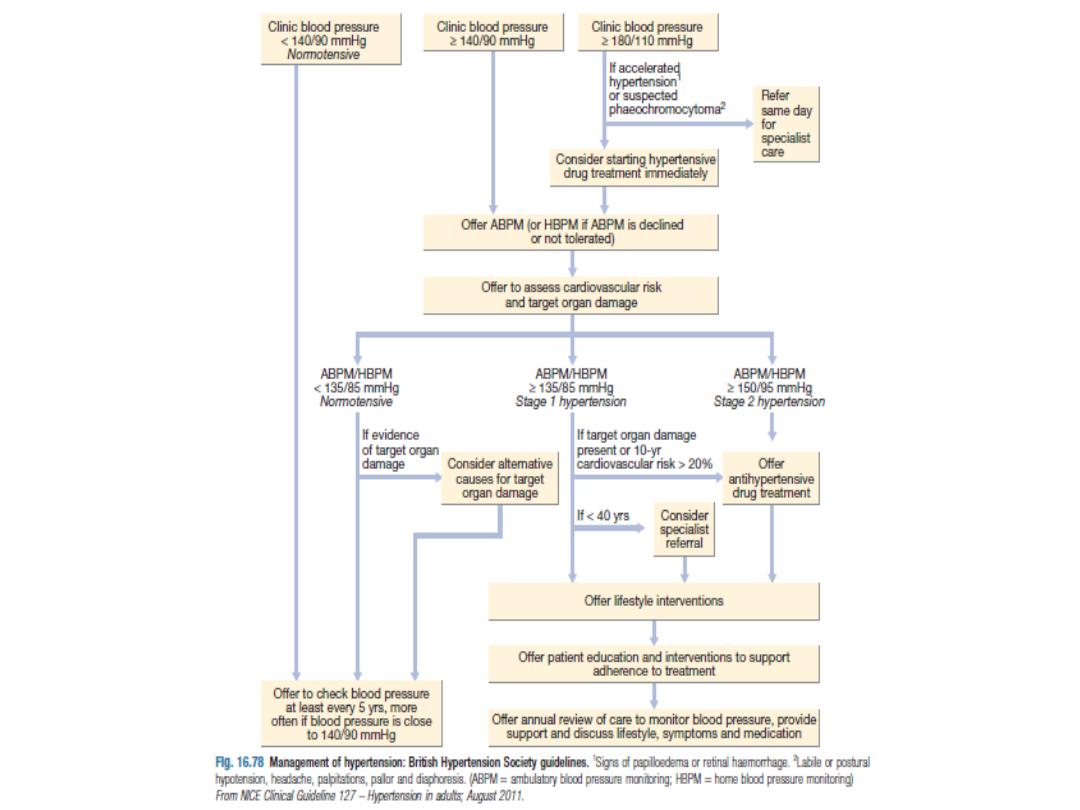

Intervention thresholds

Systolic BP and diastolic BP are both

powerful predictors of cardiovascular risk. The British

Hypertension Society management guidelines therefore

utilise both readings, and treatment should be initiated if

they exceed the given threshold.

Patients with diabetes or cardiovascular

disease are at particularly high risk and the threshold for

initiating antihypertensive therapy is therefore lower (≥

140/90 mmHg) in these patient groups. The thresholds

for treatment in the elderly are the same as for younger

patients.

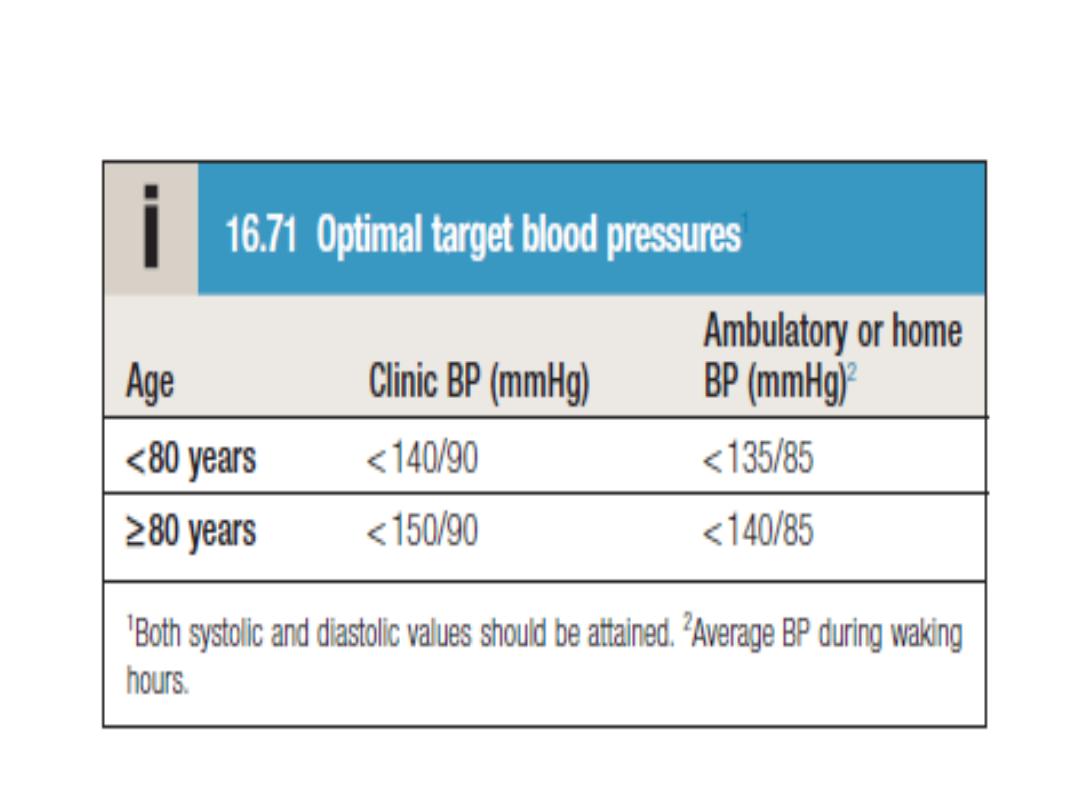

Treatment targets

Non-drug therapy

Appropriate Lifestyle Measures

Correcting Obesity

Restricting Salt Intake

Taking Regular Physical Exercise And Increasing

Consumption Of Fruit And Vegetables can All

Lower BP

Drug therapy

Thiazides The mechanism of action of

these drugs is incompletely understood and it may

take up to a month for the maximum effect to be

observed. An appropriate daily dose is 2.5 mg

bendroflumethiazide or 0.5 mg cyclopenthiazide.

More potent loop diuretics, such as

furosemide (40 mg daily) or bumetanide (1 mg daily),

have few advantages over thiazides in the treatment

of hypertension, unless there is substantial renal

impairment or they are used in conjunction with an

ACE inhibitor.

ACE inhibitors (enalapril 20 mg daily,

ramipril 5–10 mg daily or lisinopril 10–40 mg daily) are

effective and usually well tolerated. They should be

used with care in patients with impaired renal function

or renal artery stenosis because they can reduce

glomerular filtration rate and precipitate renal failure.

Electrolytes and creatinine should be

checked before and 1–2 weeks after commencing

therapy. Side-effects include first-dose hypotension,

cough, rash, hyperkalaemia and renal dysfunction.

Angiotensin receptor blockers ARBs

(irbesartan 150–300 mg daily, valsartan 40–160 mg

daily) have similar efficacy to ACE inhibitors but

they do not cause cough and are better tolerated.

Calcium channel antagonists

Amlodipine (5–10 mg daily) and

nifedipine

(30–90 mg daily) are effective and usually well-

tolerated antihypertensive drugs that are

particularly useful in older people.

Side-effects include flushing,

palpitations and fluid retention. The rate-limiting

calcium channel antagonists (diltiazem 200–300

mg daily, verapamil 240 mg daily) can be useful

when hypertension coexists with angina but may

cause bradycardia. The main side-effect of

verapamil is constipation.

Beta-blockers These are no longer used

as first-line antihypertensive therapy, except in

patients with another indication for the drug such as

angina.

Metoprolol (100–200 mg daily), atenolol

(50–100 mg daily) and bisoprolol (5–10 mg daily),

which preferentially block cardiac β1-adrenoceptors,

should be used rather than non-selective agents that

also block β2- drenoceptors, which mediate

vasodilatation and bronchodilatation.

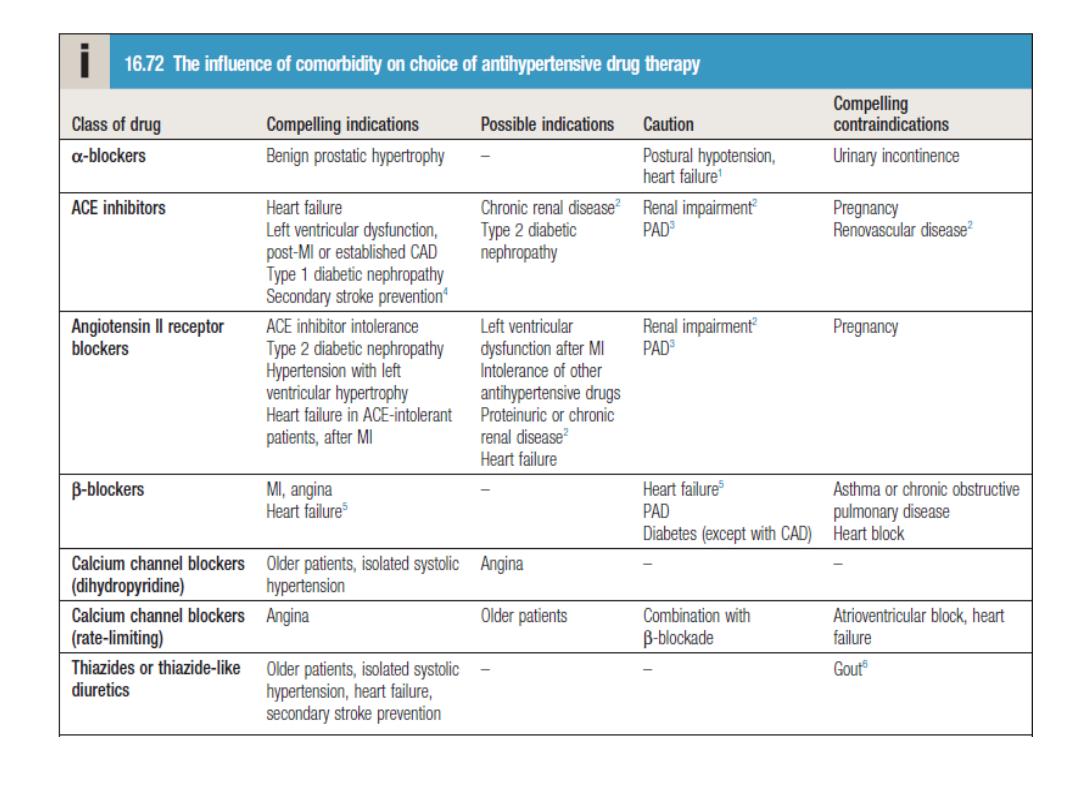

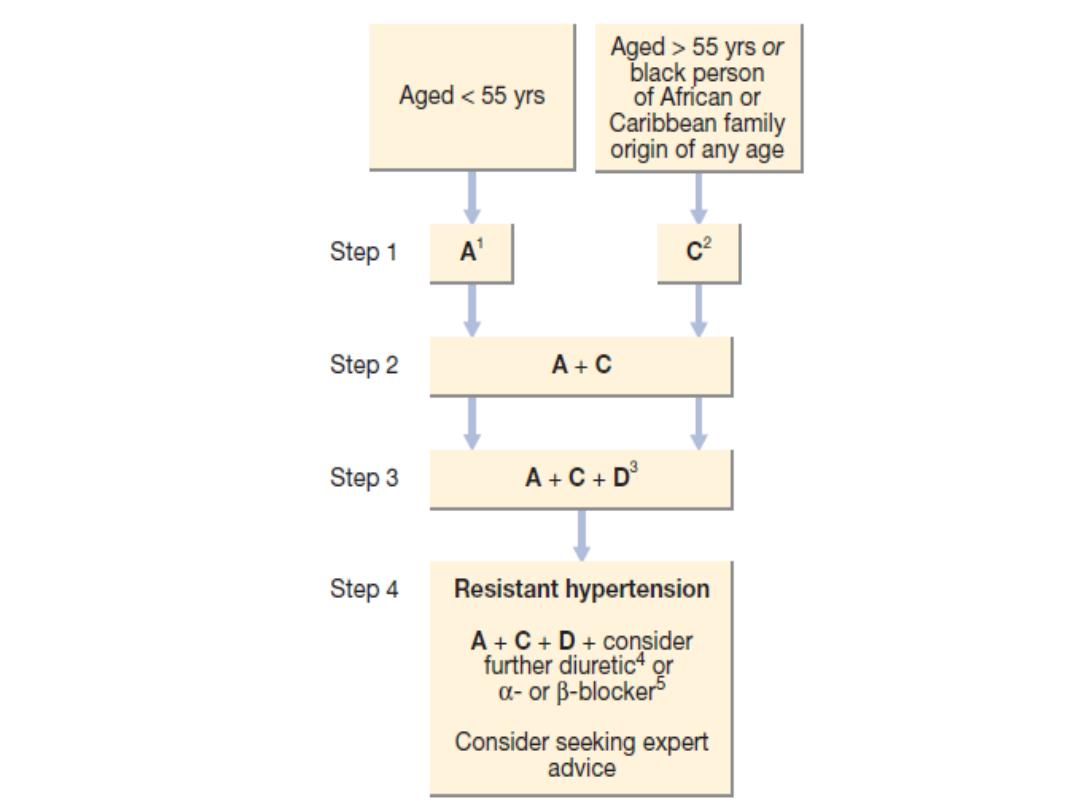

Choice of antihypertensive drug

The choice of antihypertensive therapy is

initially dictated by the patient’s age and ethnic

background, although cost and convenience will

influence the exact drug and preparation used.

Response to initial therapy and side-effects guide

subsequent treatment.

Comorbid conditions also have an

influence on initial drug selection (Box 16.72); for

example, a β-blocker might be the most appropriate

treatment for a patient with angina. Thiazide diuretics

and dihydropyridine calcium channel antagonists are

the most suitable drugs for treatment in older people.

Combination therapy

Although some patients can be treated

with a single antihypertensive drug, a combination of

drugs is often required to achieve optimal control.

Combination therapy may be desirable for

other reasons; for example, low-dose therapy with two

drugs may produce fewer unwanted effects than

treatment with the maximum dose of a single drug.

Some drug combinations have

complementary or synergistic actions; for example,

thiazides increase activity of the renin–angiotensin

system, while ACE inhibitors block it.

Refractory hypertension

Refractory hypertension refers to the

situation where multiple drug treatments do not give

adequate control of BP. Although this may be due to

genuine resistance to therapy in some cases, a more

common cause of treatment failure is non-adherence to

drug therapy.

Resistant hypertension can also be caused by

failure to recognise an underlying cause, such as renal

artery stenosis or phaeochromocytoma.

There is no easy solution to problems with

adherence but simple treatment regimens, attempts to

improve rapport with the patient and careful supervision

can all help. Spironolactone is a particularly useful addition

in patients with treatment-resistant hypertension.

Accelerated hypertension

Accelerated or malignant hypertension is

a rare condition that can complicate hypertension of

any aetiology. It is characterised by accelerated

microvascular damage with necrosis in the walls of

small arteries and arterioles (fibrinoid necrosis) and by

intravascular thrombosis.

The diagnosis is based on evidence of

high BP and rapidly progressive end-organ damage,

such as retinopathy (grade 3 or 4), renal dysfunction

(especially proteinuria) and/or hypertensive

encephalopathy. Left ventricular failure may occur

and, if this is untreated, death occurs within months>

Management

In accelerated phase hypertension, lowering BP too

quickly may compromise tissue perfusion due to altered

autoregulation and can cause cerebral damage, including occipital

blindness, and precipitate coronary or renal insufficiency. Even in

the presence of cardiac failure or hypertensive encephalopathy, a

controlled reduction to a level of about 150/90 mmHg over a

period of 24–48 hours is ideal.

In most patients, it is possible to avoid parenteral

therapy and bring BP under control with bed rest and oral drug

therapy.

Intravenous or intramuscular labetalol (2 mg/min

to a maximum

of 200 mg), intravenous GTN (0.6–1.2 mg/hr), intramuscular

hydralazine (5 or 10 mg aliquots repeated at half-hourly intervals)

and intravenous sodium nitroprusside (0.3–1.0 μg/kg body

weight/ min) are all effective but require careful supervision,

preferably in a high-dependency unit.