Cardiology Lectures Dr. Ahmed Moyed Hussein

Acute coronary syndrome

Acute coronary syndrome is a term that encompasses both unstable angina and myocardial infarction (MI). unstable angina characterized by new-onset or rapidly worsening angina (crescendo angina), angina on minimal exertion or angina at rest in the absence of myocardial damage. In contrast, MI occurs when symptoms occur at rest and there is evidence of myocardial necrosis, as demonstrated by an elevation in cardiac enzymes (troponin or creatine kinase-MB isoenzyme).

The culprit lesion is usually a complex ulcerated or fissured atheromatous plaque with adherent platelet-rich thrombus, clotting system activation and local coronary artery spasm.

Clinical features:

Pain is the cardinal symptom of an acute coronary syndrome but breathlessness, vomiting and collapse are common features. The pain occurs in the same sites as angina but is usually more severe and lasts longer; it is often described as a tightness, heaviness or constriction in the chest. In acute MI, the pain can be excruciating, and the patient’s expression and pallor may vividly convey the seriousness of the situation.Most patients are breathless and, in some, this is the only symptom. Indeed, MI may pass unrecognized. Painless or ‘silent’ MI is particularly common in older patients or those with diabetes mellitus. If syncope occurs, it is usually due to an arrhythmia or profound hypotension. Vomiting and sinus bradycardia are often due to vagal stimulation and are particularly common in patients with inferior MI. Sudden death, from ventricular fibrillation or asystole, may occur immediately and often within the first hour. If the patient survives this most critical stage, the liability to dangerous arrhythmias remains, but diminishes as each hour goes by. The development of cardiac failure reflects the extent of myocardial ischaemia and is the major cause of death in those who survive the first few hours.

Investigations:

Electrocardiography:

The ECG is central to confirming the diagnosis. The initial ECG may be normal or nondiagnostic in one-third of cases. Repeated ECGs are important, especially where the diagnosis is uncertain or the patient has recurrent or persistent symptoms.

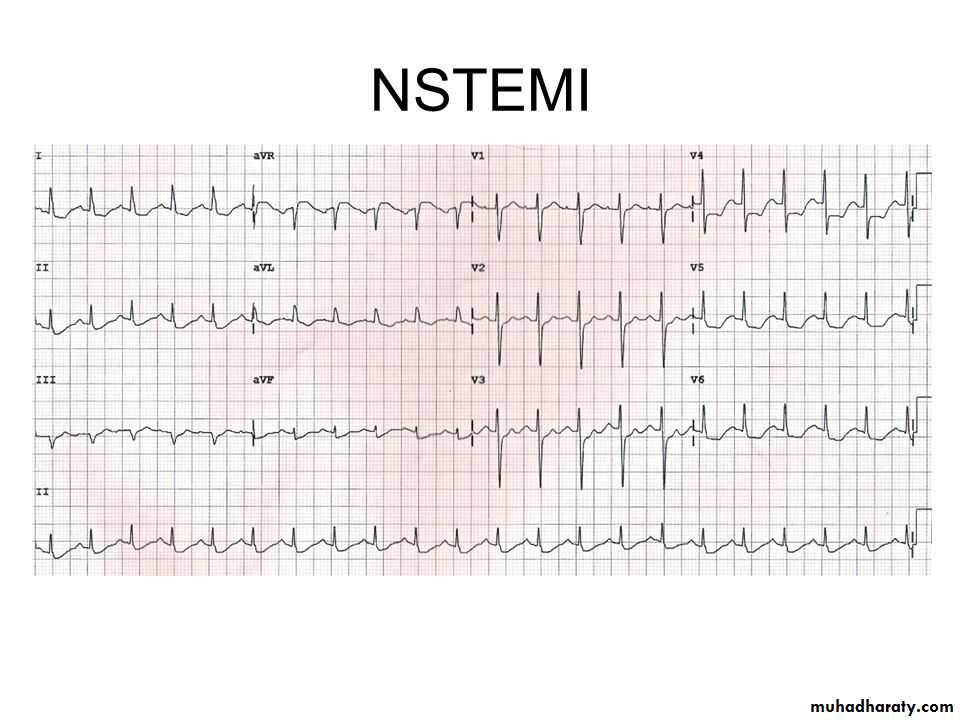

The earliest ECG change is usually ST-segment deviation. According to ST segment changes acute coronary syndrome classified into: ST segment elevation myocardial infarction acute coronary syndrome (STE-ACS) and non ST elevation acute coronary syndrome(NSTE-ACS). With proximal occlusion of a major coronary artery, ST-segment elevation (or new bundle branch block) is seen initially, with later diminution in the size of the R wave and, in transmural (full-thickness) infarction, development of a Q wave. Subsequently, the T wave becomes inverted because of a change in ventricular

repolarisation; this change persists after the ST segment has returned to normal.

In non-ST segment elevation acute coronary syndrome, there is usually ST-segment depression and T-wave changes. In the presence of infarction, this may be accompanied by some loss of R waves in the absence of Q waves.

The ECG changes are best seen in the leads that ‘face’ the ischaemic or infarcted area. When there has been anteroseptal infarction, abnormalities are found in one or more leads from V1 to V4, while anterolateral infarction produces changes from V4 to V6, in aVL and in lead I. Inferior infarction is best shown in leads II, III and aVF, while, at the same time, leads I, aVL and the anterior chest leads may show ‘reciprocal’ changes of ST depression.

Fig: Anterior STEMI inferolateral STEMI

Fig: NSTE- ACS

Plasma cardiac biomarkers:In unstable angina, there is no detectable rise in cardiac biomarkers or enzymes, and the initial diagnosis is made from the clinical history and ECG only. In contrast, MI causes a rise in the plasma concentration of enzymes and

proteins that are normally concentrated within cardiac cells. These biochemical markers are creatine kinase (CK-MB), and the cardio-specific proteins, troponins T and I. Admission and serial (usually daily) estimations are helpful because it is the change in plasma concentrations of these markers that confirms the diagnosis of MI. CK starts to rise at 4–6 hours, peaks at about 12 hours and falls to normal within 48–72 hours. The most sensitive markers of myocardial cell damage are the cardiac troponins T and I, which are released within 4–6 hours and remain elevated for up to 2 weeks.

Other blood tests:

A leucocytosis is usual, reaching a peak on the first day. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) are also elevated.

Chest X-ray:

This may demonstrate pulmonary oedema that is not evident on clinical examination. The heart size is often normal but there may be cardiomegaly due to pre-existing myocardial damage.Echocardiography:

This is useful for assessing ventricular function and for detecting important complications, such as mural thrombus, cardiac rupture, ventricular septal rupture, mitral regurgitation and pericardial effusion.Immediate management: the first 12 hours

Patients should be admitted urgently to hospital because there is a significant risk of death or recurrent myocardial ischaemia during the early unstable phase, and appropriate medical therapy can reduce the incidence of these by at least 60%. Patients are usually managed in a dedicated cardiac unit, where the necessary expertise, monitoring and resuscitation facilities can be concentrated. If there are no complications, the patient can be mobilized from the second day and discharged after 3–5 days.Analgesia:

Adequate analgesia is essential, not only to relieve distress but also to lower adrenergic drive and thereby reduce vascular resistance, BP, infarct size and susceptibility to ventricular arrhythmias. Intravenous opiates (morphine sulphate 5–10 mg or diamorphine 2.5–5 mg) and antiemetics (initially, metoclopramide 10 mg) should be administered

Antithrombotic therapy:

Antiplatelet therapy:

In patients with acute coronary syndrome, oral administration of 75–325 mg aspirin daily improves survival, with a 25% relative risk reduction in mortality. The first tablet (300 mg) should be given orally(chewable) within the first 12 hours and therapy should be continued indefinitely if there are no side-effects. In combination with aspirin, the early (within 12 hours) use of clopidogrel (600 mg, followed by 75 mg daily) confers a further reduction in ischaemic events.

Anticoagulants:

Anticoagulation reduces the risk of thromboembolic complications, and prevents re-infarction in the absence of reperfusion therapy or after successful thrombolysis. Anticoagulation can be achieved using unfractionated heparin, fractioned (low-molecular weight) heparin or a pentasaccharide. Anticoagulation should be continued for 8 days or until discharge from hospital or coronary revascularisation.

Anti-anginal therapy:

Sublingual glyceryl trinitrate (300–500 μg) is a valuable first-aid measure in unstable angina or threatened infarction, and intravenous nitrates (glyceryl trinitrate 0.6–1.2 mg/hr or isosorbide dinitrate 1–2 mg/hr) are useful for the treatment of left ventricular failure and the relief of recurrent or persistent ischaemic pain.

Intravenous β-blockers (e.g. atenolol 5–10 mg or metoprolol 5–15 mg given over 5 mins) relieve pain, reduce arrhythmias and improve short-term mortality

in patients who present within 12 hours of the onset of symptoms. However, they should be avoided if there is heart failure (pulmonary oedema), hypotension (systolic BP < 105 mmHg) or bradycardia (heart rate < 65/min).

A dihydropyridine calcium channel antagonist (e.g. nifedipine or amlodipine) can be added to the β-blocker if there is persistent chest discomfort but may cause tachycardia if used alone. Because of their rate-limiting action, verapamil and diltiazem are the calcium channel antagonists of choice if a β-blocker is contraindicated.

Reperfusion therapy ( to reopen the occluded artery):

Non-ST segment elevation acute coronary syndrome:Immediate emergency reperfusion therapy has no demonstrable benefit in patients with non-ST segment elevation MI and thrombolytic therapy may be harmful.

ST segment elevation acute coronary syndrome:

Immediate reperfusion therapy (by primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention or thrombolysis) restores coronary artery patency, preserves left ventricular function and improves survival. Successful therapy is associated with pain relief, resolution of acute ST elevation and, sometimes, transient arrhythmias (e.g. idioventricular rhythm).

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI):

This is the treatment of choice for ST segment elevation MI. Outcomes are best when it is used in combination with intracoronary stent implantation. In comparison to thrombolytic therapy, it is associated with a greater reduction in the risk of death, recurrent MI or stroke.

Thrombolysis:

The appropriate use of thrombolytic therapy can reduce hospital mortality by 25–50% and this survival advantage is maintained for at least 10 years. The benefit is greatest in those patients who receive treatment within the first few hours, these include: Streptokinase, tissue plasminogen activator(tPA) (Alteplase, tenecteplase (TNK) and reteplase (rPA)). The major hazard of thrombolytic therapy is bleeding.

For some patients, thrombolytic therapy is contraindicated or fails to achieve coronary arterial reperfusion. Early emergency PCI may then be considered, particularly where there is evidence of cardiogenic shock.

Absolute Contraindications to thrombolytic therapy:

Any prior intracranial hemorrhage

Known structural cerebral vascular lesion (e.g., AV malformation)

Malignant intracranial neoplasm

Ischemic stroke in last 3 months

Suspected aortic dissection

Active bleeding or bleeding diathesis

Closed head or facial trauma in last 3 months

Complications of acute coronary syndrome:

Complications are seen in all forms of acute coronary syndrome, although the frequency and extent vary with the severity of ischaemia and infarction. Major mechanical and structural complications are seen only with significant, often transmural, MI.

Arrhythmias:

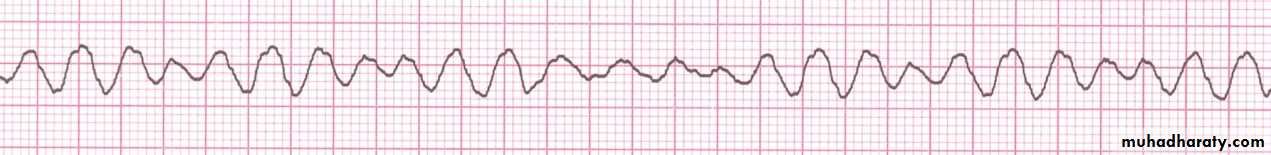

Ventricular fibrillation:This occurs in 5–10% of patients who reach hospital and is thought to be the major cause of death in those who die before receiving medical attention. Prompt defibrillation restores sinus rhythm and is life-saving. The prognosis of patients with early ventricular fibrillation (within the first 48 hours) who are successfully and promptly resuscitated is identical to that of patients who do not suffer ventricular fibrillation. Patients with VF are unconscious, cyanosed with detectable pulse or BP, it need urgent DC defibrillation.

Fig: Ventricular Fibrillation

Ischaemia:Post-infarct angina occurs in up to 50% of patients treated with thrombolysis. Most patients have a residual stenosis in the infarct-related vessel, despite successful thrombolysis, and this may cause angina.

Acute circulatory failure:

Acute circulatory failure usually reflects extensive myocardial damage and indicates a bad prognosis. All the other complications of MI are more likely to occur when acute heart failure is present.Pericarditis:

This only occurs following infarction and is particularly common on the second and third days. The patient may recognize that a different pain has developed, even though it is at the same site, and that it is positional and tends to be worse or sometimes only present on inspiration.A pericardial rub may be audible. Opiate-based analgesia should be used. Non-steroidal (NSAIDs) and steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may increase the risk

of aneurysm formation and myocardial rupture in the early recovery period, and so should be avoided.

The post-MI syndrome (Dressler’s syndrome) is characterized by persistent fever, pericarditis and pleurisy, and is probably due to autoimmunity. The symptoms tend to occur a few weeks or even months after the infarct and often subside after a few days; prolonged or severe symptoms may require treatment with high-dose aspirin, NSAIDs or even corticosteroids.

Mechanical complications:

Part of the necrotic muscle in a fresh infarct may tear or rupture, with devastating consequences:

• Rupture of the papillary muscle: can cause acute pulmonary oedema and shock due to the sudden onset of severe mitral regurgitation, which presents

with a pansystolic murmur and third heart sound.

• Rupture of the interventricular septum: causes left-to right shunting through a ventricular septal defect. This usually presents with sudden haemodynamic deterioration accompanied by a new loud pansystolic murmur radiating to the right sternal border, but may be difficult to distinguish from acute mitral regurgitation. Doppler echocardiography and right heart catheterisation will confirm the diagnosis. Without prompt surgery, the condition is usually fatal.

• Rupture of the ventricle: may lead to cardiac tamponade and is usually fatal, although it may rarely be possible to support a patient with an incomplete rupture until emergency surgery is performed.

Embolism:

Thrombus often forms on the endocardial surface of freshly infarcted myocardium. This can lead to systemic embolism and occasionally causes a stroke or ischaemic limb.Impaired ventricular function, remodeling and ventricular aneurysm:

Acute transmural MI is often followed by thinning and stretching of the infarcted segment (infarct expansion). This leads to an increase in wall stress with progressive dilatation and hypertrophy of the remaining ventricle (ventricular remodelling). As the ventricle dilates, it becomes less efficient and heart failure may supervene. ACE inhibitor therapy reduces late ventricular remodeling and can prevent the onset of heart failure.A left ventricular aneurysm develops in approximately 10% of patients with MI and characterized by persistent ST elevation on the ECG, and sometimes an unusual bulge from the cardiac silhouette on the chest X-ray. Echocardiography is diagnostic.

Later in-hospital management:

Late management of MI is summarised inMobilization and rehabilitation

The necrotic muscle of an acute myocardial infarct takes 4–6 weeks to be replaced with fibrous tissue and it is conventional to restrict physical activities during this period. When there are no complications, the patient can mobilise on the second day, return home in 3–5 days and gradually increase activity, with the aim of returning to work in 4–6 weeks. The majority of patients may resume driving after 4–6 weeks.Prognosis:

In almost one-quarter of all cases of MI, death occurs within a few minutes without medical care. Half the deaths occur within 24 hours of the onset of symptoms and about 40% of all affected patients die within the first month. The prognosis of those who survive to reach hospital is much better, with a 28-day survival of more than 85%. Patients with unstable angina have a mortality of approximately half that of those patients with MI.