Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Dr.Ahmed Hussein Jasim (F.I.B.M.S) (respiratory)

COPD) is a preventable and treatable disease characterised by persistent

airflow limitation that is usually progressive, and associated with an

enhanced chronic inflammatory response in the airways and the lung to

noxious particles or gases.

Related diagnoses include chronic bronchitis (cough and sputum on most

days for at least 3 months, in each of 2 consecutive years) and

emphysema (abnormal permanent enlargement of the airspaces distal to

the terminal bronchioles, accompanied by destruction of their walls and

without obvious fibrosis).

•

Extra-pulmonary effects include weight loss and skeletal muscle dysfunction.

Commonly associated comorbid conditions include

•

cardiovascular disease,

•

cerebrovascular disease,

•

the metabolic syndrome,

•

osteoporosis, depression and lung cancer.

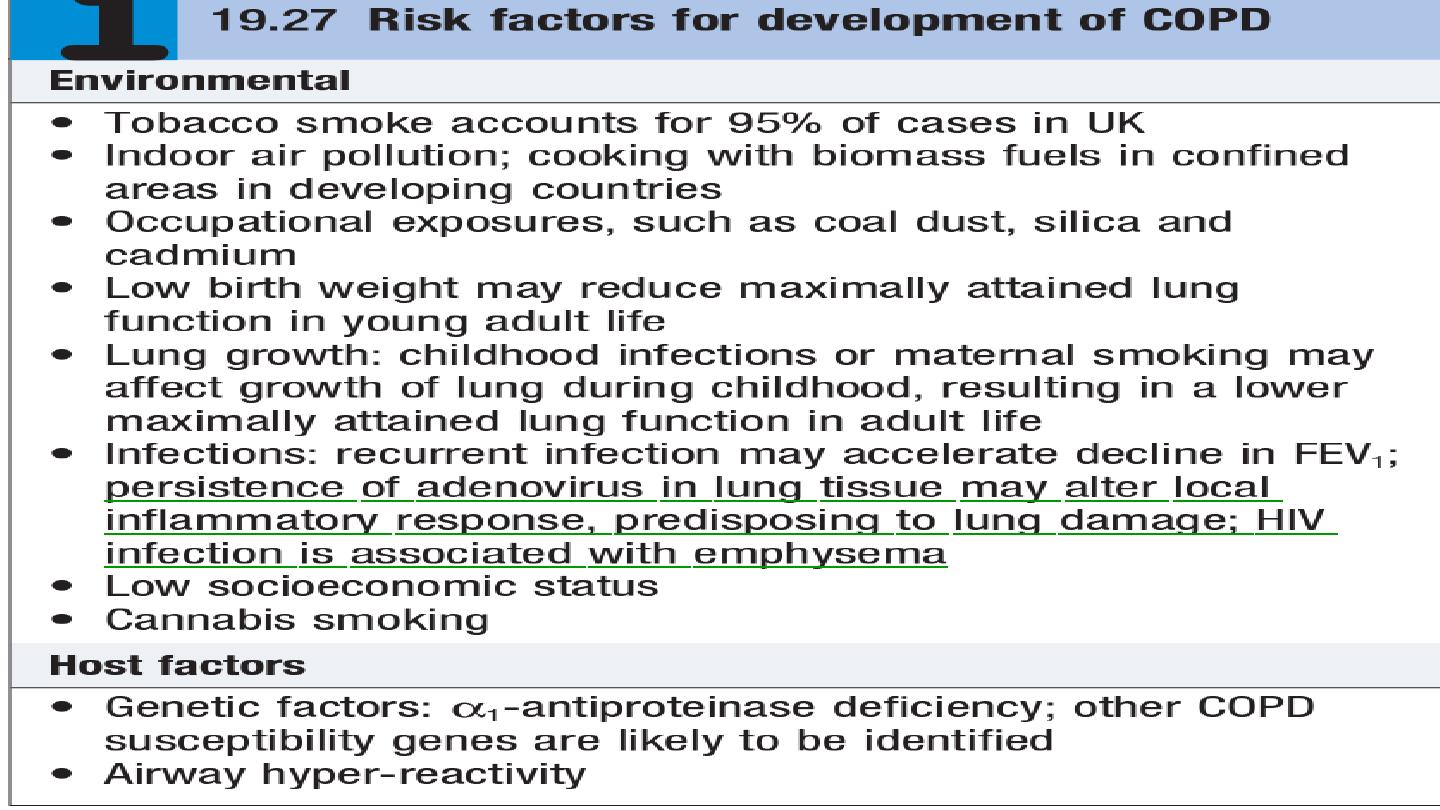

Epidemiology and aetiology

The prevalence of COPD is directly related to the prevalence of tobacco

smoking and, in low- and middle income countries and the use of biomass

fuels.

Cigarette smoking represents the most significant risk factor, and the risk

of developing COPD relates to both the amount and the duration of

smoking. It is unusual to develop COPD with less than 10 pack years (1

pack year = 20 cigarettes/day/year) and not all smokers develop the

condition, suggesting that individual susceptibility factors are important.

Pathophysiology

COPD has both pulmonary and systemic components .The presence of

airflow limitation, combined with premature airway closure, leads to gas

trapping and hyperinflation, reducing pulmonary and chest wall compliance.

Pulmonary hyperinflation also flattens the diaphragmatic muscles and leads

to an increasingly horizontal alignment of the intercostal muscles, placing

the respiratory muscles at a mechanical disadvantage.

Clinical features

COPD should be suspected in any patient over the age of 40 years who

presents with symptoms of chronic bronchitis and/or breathlessness.

Cough and associated sputum production are usually the first symptoms,

often referred to as a ‘smoker’s cough’.

Haemoptysis may complicate exacerbations of COPD but should not be

attributed to COPD without thorough investigation.

Breathlessness usually precipitates the presentation to health care. The

severity should be quantified by the modified MRC dyspnoea scale (Medical

Research Council).

Physical signs

•

Breath sounds are typically quiet.

•

Crackles may accompany infection but, if persistent, raise the possibility of

bronchiectasis.

•

Finger clubbing is not a feature of COPD and should trigger further

investigation for lung cancer or fibrosis.

•

Pitting oedema should be sought but the frequently used term ‘cor

pulmonale’ is actually a misnomer, as the right heart seldom ‘fails’ in

COPD and the occurrence of oedema usually relates to failure of salt and

water excretion by the hypoxic hypercapnic kidney.

Two classical phenotypes have been described: ‘pink puffers’ and ‘blue

bloaters’

The former are typically thin and breathless, and maintain a normal PaCO2

until the late stage of disease. The blue bloaters’ develop (or tolerate)

hypercapnia earlier and may develop oedema and secondary polycythaemia.

In practice, these phenotypes often overlap.

Investigations

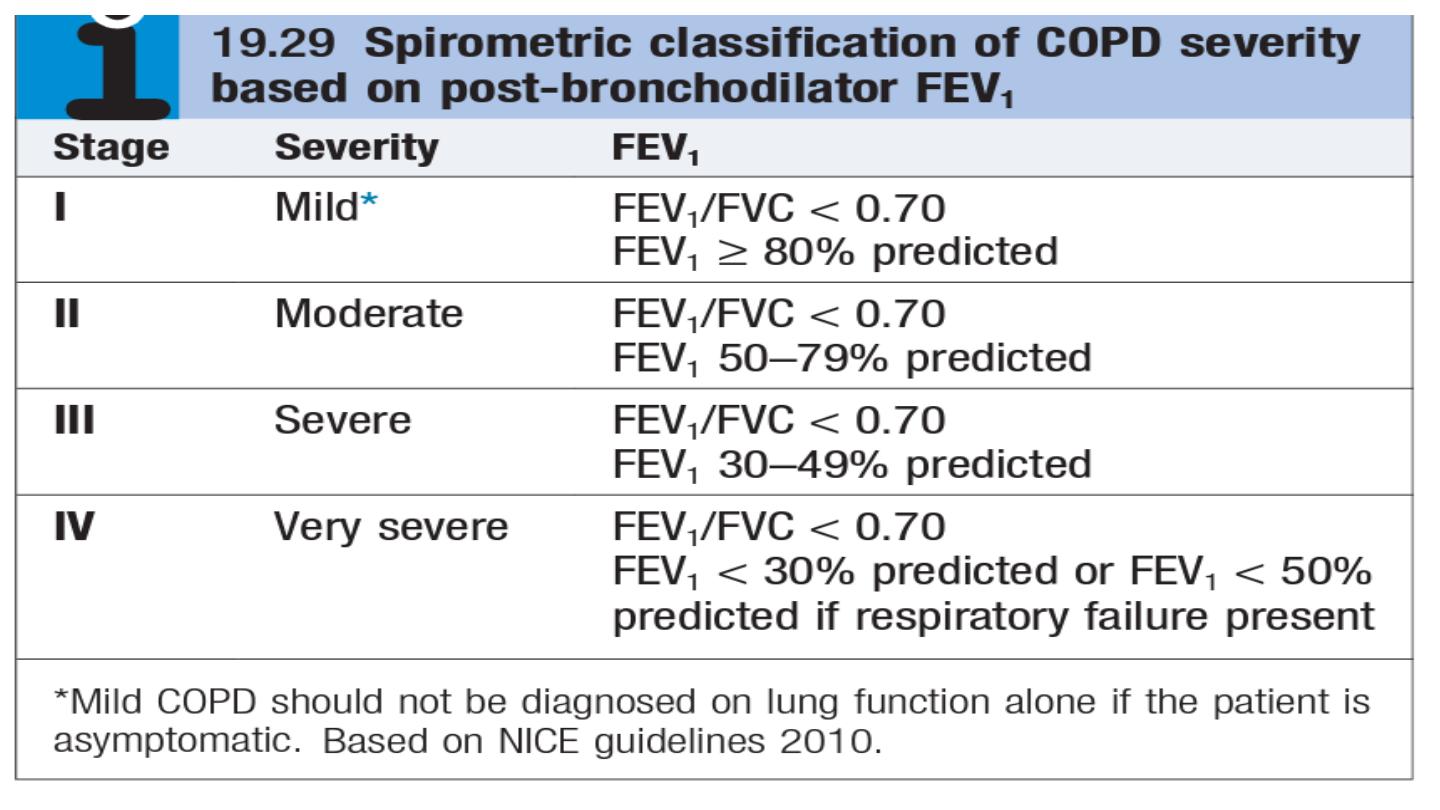

The diagnosis requires objective demonstration of airflow obstruction by

spirometry and is established when the post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC is less

than 70%.

The severity of COPD may be defined in relation to the post-

bronchodilator FEV1 .

A low peak flow is consistent with COPD but is non-specific, does not

discriminate between obstructive and restrictive disorders, and may

underestimate the severity of airflow limitation.

Measurement of lung volumes provides an assessment of hyperinflation.

This is generally performed by using

the helium dilution techniques

. in

patients with severe COPD, and with large bullae in particular,

body

plethysmography

is preferred because the use of helium may underestimate

lung volumes. Emphysema is suggested by a low gas transfer value.

Exercise tests provide an objective assessment of exercise tolerance and a

baseline for judging response to bronchodilator therapy or rehabilitation

programmes; they may also be valuable when assessing prognosis.

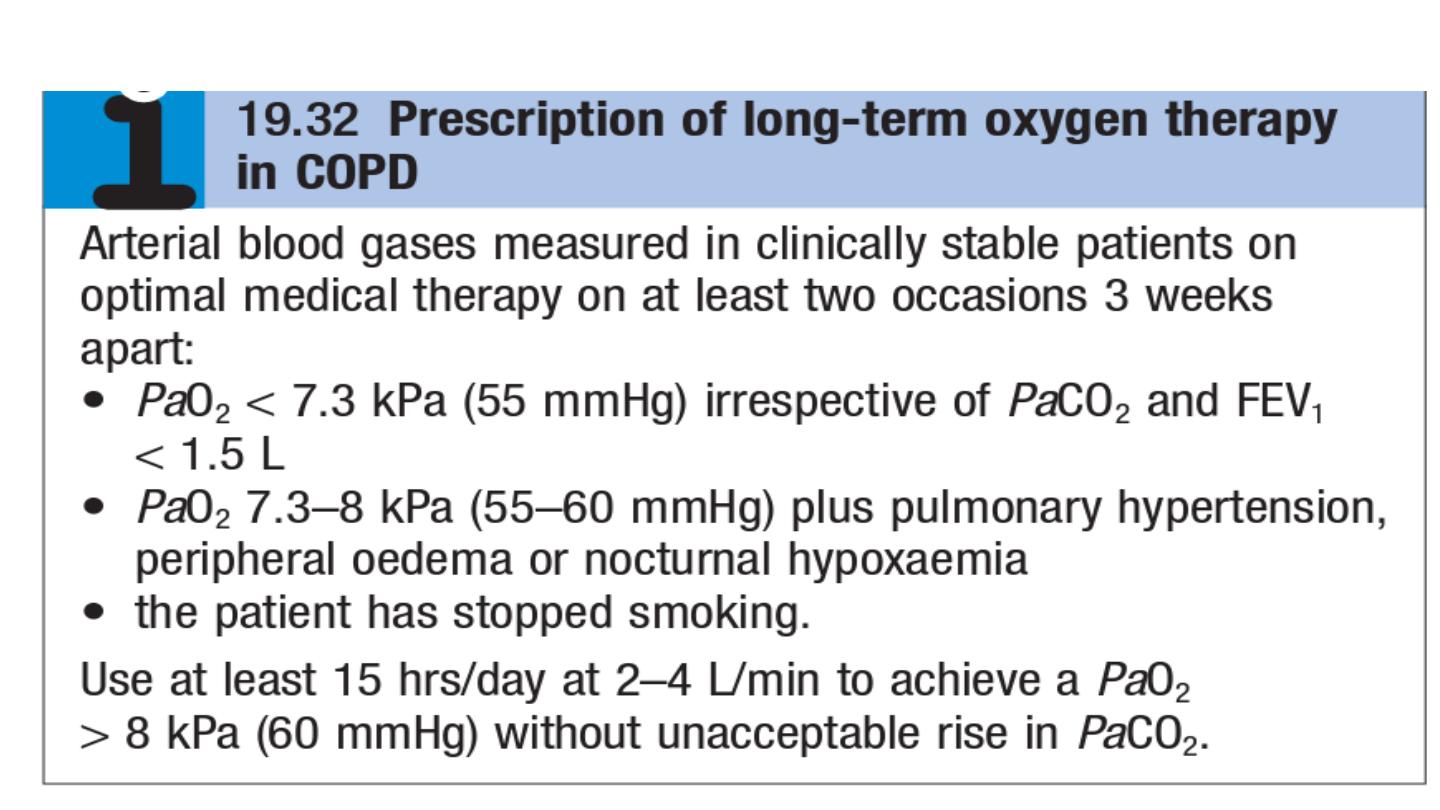

Pulse oximetry of less than 93% may indicate the need for referral for a

domiciliary oxygen assessment.

chest X-ray is essential to identify alternative diagnoses, such as cardiac

failure, other complications of smoking such as lung cancer, and the

presence of bullae.

A blood count is useful to exclude anaemia or polycythaemia.

HRCT is likely to play an increasing role in the assessment of COPD, as it

allows the detection, characterization and quantification of emphysema and

is more sensitive than a chest X-ray for detecting bullae.

α1-antiproteinase should be assayed in younger patients with

predominantly basal emphysema.

Management

•

possible to help breathlessness

•

reduce the frequency and severity of exacerbations.

•

enhance the health status.

•

improve the prognosis.

•

Reducing exposure to noxious particles and gases, the role of smoking

in the development and progression of COPD, with advice and

assistance to help them stop. Reducing the number of cigarettes

smoked each day has little impact on the course and prognosis of

COPD, but complete cessation is accompanied by an improvement in

lung function and deceleration in the rate of FEV1 decline .

Bronchodilators

Bronchodilator therapy is central to the management of breathlessness.

The inhaled route is preferred and a number of different agents,

Short-acting bronchodilators, such as the β2-agonists salbutamol and

terbutaline, or the anticholinergic ipratropium bromide, may be used for

patients with mild disease.

Longer acting bronchodilators, such as the β2-agonists salmeterol,

formoterol and indacaterol, or the anticholinergic tiotropium bromide, are

more appropriate for patients with moderate to severe disease.

Theophylline preparations improve breathlessness and quality of life, but

their use is limited by side-effects, unpredictable metabolism and drug

interactions

Corticosteroids

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) reduce the frequency and severity of

exacerbations, and are currently re commended in patients with severe

disease (FEV1 < 50%) who report two or more exacerbations requiring

antibiotics or oral steroids per year. It is more usual to prescribe a fixed

combination of an ICS and a LABA.

Oral corticosteroids are useful during exacerbations but maintenance

therapy contributes to osteoporosis and impaired skeletal muscle function

and should be avoided.

Pulmonary rehabilitation

Exercise should be encouraged at all stages and patients reassured that

breathlessness, whilst distressing, is not dangerous. Most programmes

include 2–3 sessions per week for 6 and 12 weeks.

Oxygen therapy

Surgical intervention

Patients in whom large bullae compress surrounding normal lung tissue,

who otherwise have minimal airflow limitation and a lack of generalised

emphysema, may be considered for

bullectomy.

Patients with predominantly upper lobe emphysema, with preserved gas

transfer and no evidence of pulmonary hypertension, may benefit from

lung volume reduction surgery (LVRS).

Lung transplantation

may benefit carefully selected patients with advanced

disease .

Other measures

Patients with COPD should be offered an annual influenza vaccination

and, as appropriate, pneumococcal vaccination.

Prognosis

The prognosis is inversely related to age and directly related to the post-

bronchodilator FEV1

poor prognostic indicators include weight loss and pulmonary

hypertension

. A composite score comprising the body mass index (B), the

degree of airflow obstruction (O), a measurement of dyspnoea (D) and

exercise capacity (E) may assist in predicting death from respiratory and

other causes

Respiratory failure, cardiac disease and lung cancer represent common

modes of death.

Smoking cessation is the only intervention that is proven to

decrease the smoking-related decline in lung function

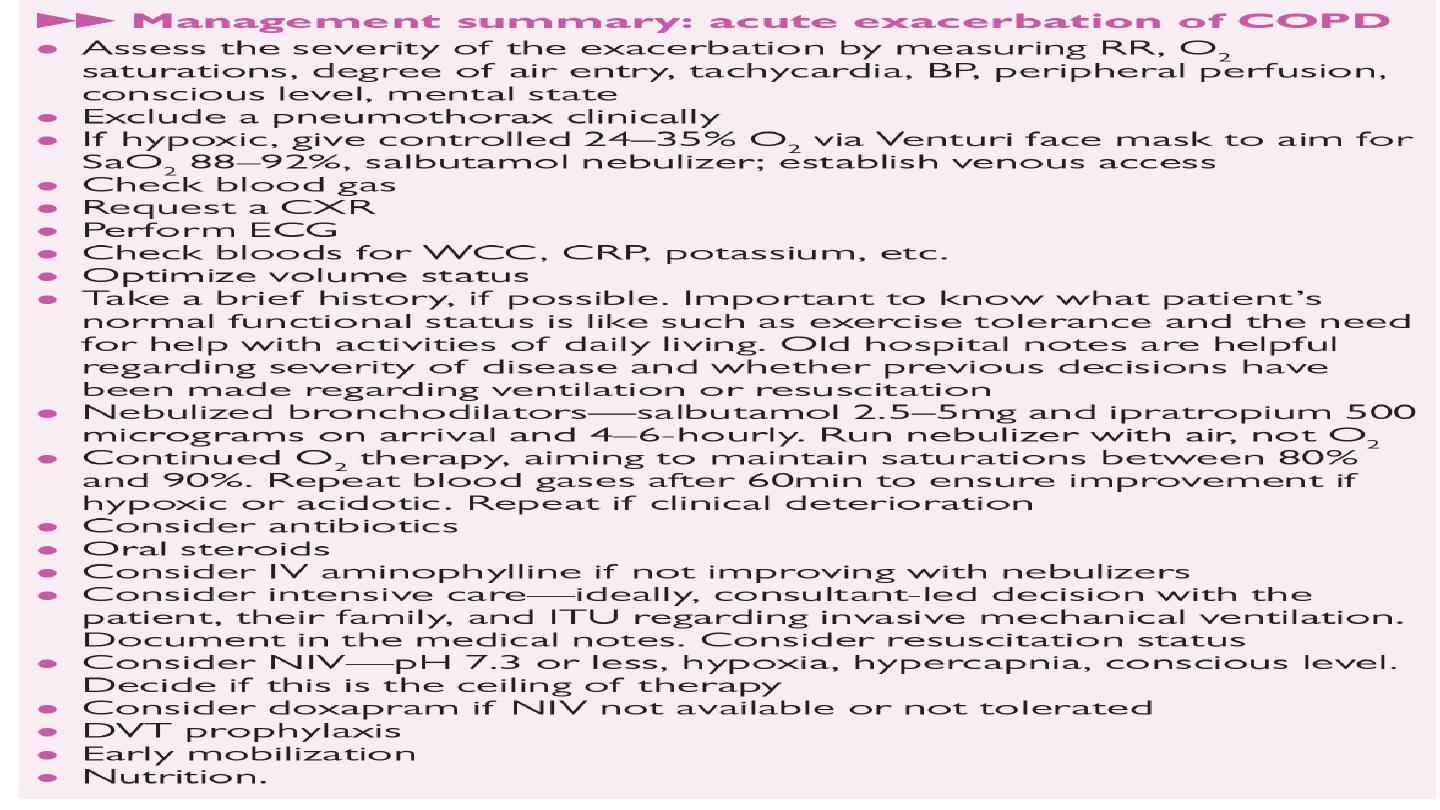

Acute exacerbations of COPD

Acute exacerbations of COPD are characterised by an increase in

symptoms and deterioration in lung function and health status.

They become more frequent as the disease progresses and are usually

triggered by bacteria, viruses or a change in air quality.

They may be accompanied by the development of respiratory failure and/

or fluid retention and are an important cause of death.

Many patients can be managed at home with the use of increased

bronchodilator therapy, a short course of oral corticosteroids and, if

appropriate, antibiotics.

The presence of cyanosis, peripheral oedema or an alteration in

consciousness indicates the need for referral to hospital.

Management

Controlled oxygen at 24% or 28% should be used with the aim of

maintaining a PaO2 above 8 kPa (60 mmHg) (or an SaO2 between 88%

and 92%) without worsening acidosis.

Nebulised short-acting β2-agonists, combined with an anticholinergic

agent (e.g. salbutamol and ipratropium), should be administered.

Oral prednisolone reduces symptoms and improves lung function. Currently,

doses of 30 mg for 10 days are recommended but shorter courses may be

acceptable.

the routine administration of antibiotics They are currently recommended,

however, for patients reporting an increase in sputum purulence, sputum

volume or breathlessness.

In most cases, simple regimens are advised, such

as an aminopenicillin or a macrolide. Co-amoxiclav is only required in

regions where β-lactamase-producing organisms are known to be common.

Exacerbations may be accompanied by the development of peripheral

oedema that usually responds to diuretics.

The use of the respiratory stimulant

doxapram

has been largely

superseded by the development of NIV, but it may be useful for a limited

period in selected patients with a low respiratory rate.

If the patient remains tachypnoeic, hypercapnic and acidotic (PaCO2 > 6 kPa,

H+

≥ 45 (pH < 7.35)), then NIV should be commenced.Its use is associated with

reduced requirements for mechanical ventilation and reduced mortality.

Mechanical ventilation may be considered in those with a reversible cause for

deterioration (e.g. pneumonia), or if PH <7.25.

Thromboprevention by subcutaneous given heparin or LMWH.

Bronchiectasis

Bronchiectasis means abnormal dilatation of the bronchi.

Chronic suppurative airway infection with sputum production, progressive

scarring and lung damage occur.

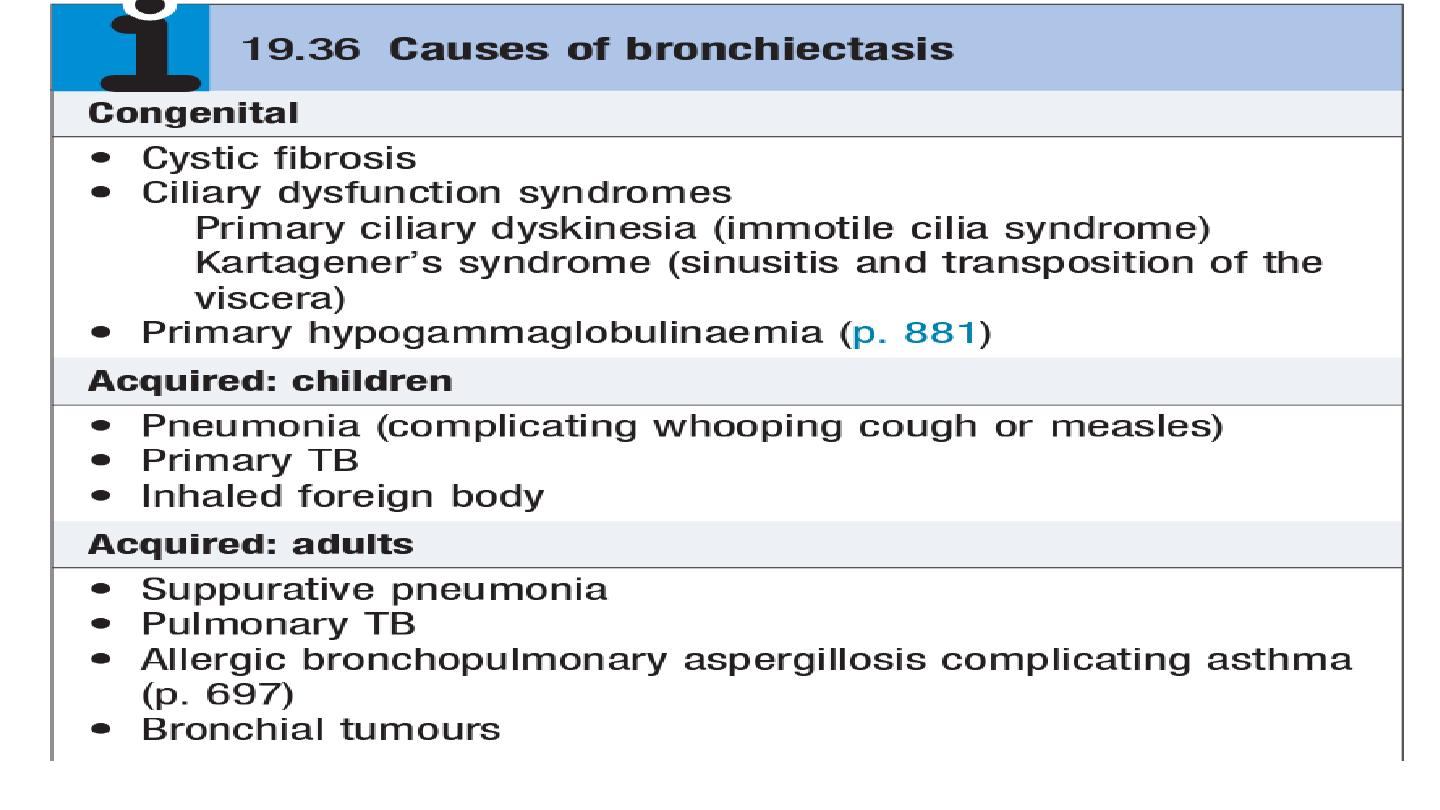

Aetiology and pathology

Tuberculosis is the most common worldwide.

Localized bronchiectasis may occur due to the accumulation of pus beyond an

obstructing bronchial lesion, such as enlarged tuberculous hilar lymph nodes, a

bronchial tumor or an inhaled foreign body (e.g. an aspirated peanut).

The bronchiectatic cavities may be lined by granulation tissue, squamous epithelium

or normal ciliated epithelium. There may also be inflammatory changes in the deeper

layers of the bronchial wall and hypertrophy of the bronchial arteries. Chronic

inflammatory and fibrotic changes are usually found in the surrounding lung tissue,

resulting in progressive destruction of the normal lung architecture in advanced cases.

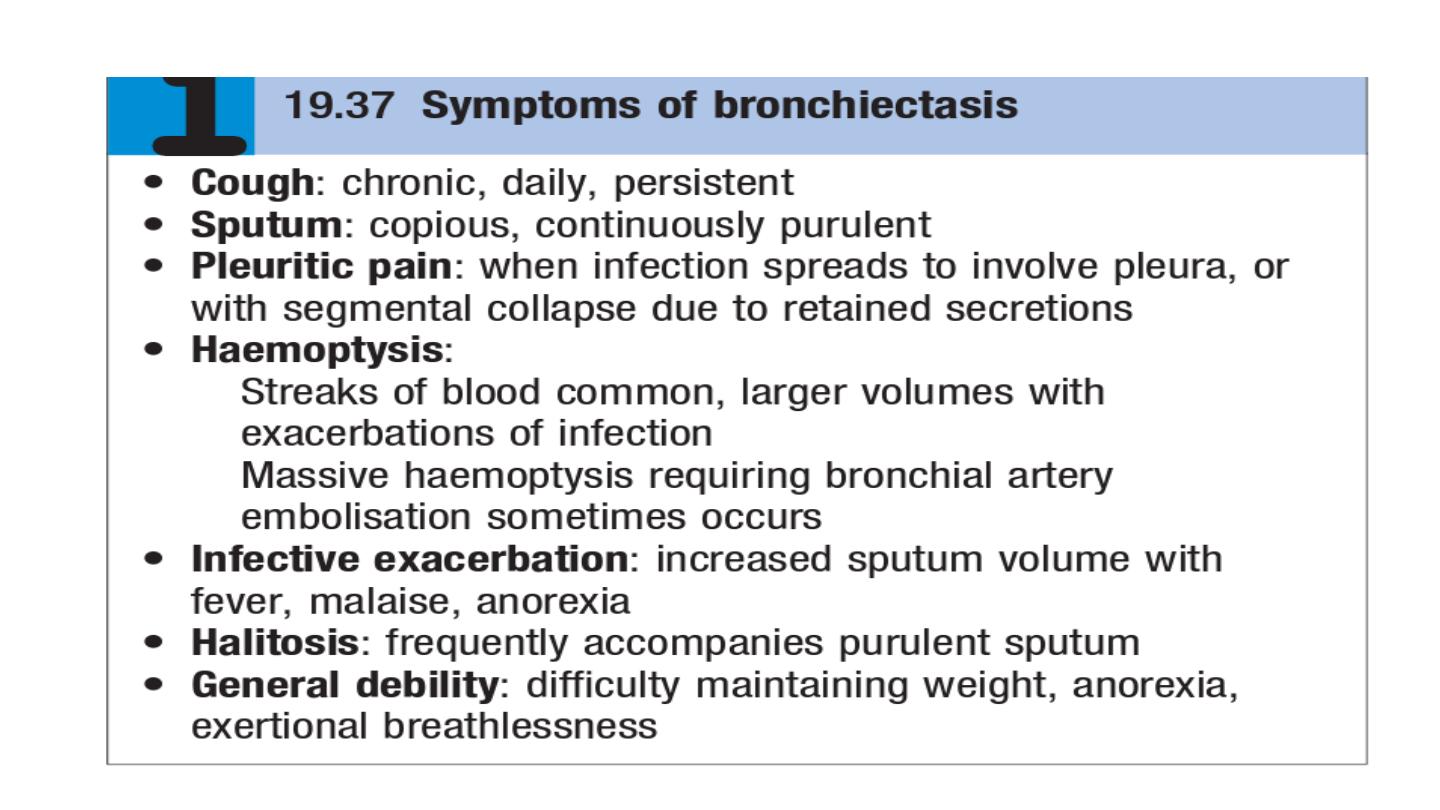

Clinical features

Investigations

common respiratory pathogens, sputum culture may reveal Pseudomonas

aeruginosa, fungi such as Aspergillus and various mycobacteria.

Frequent cultures are necessary to ensure appropriate treatment of

resistant organisms.

chest X-ray thickened airway walls, cystic bronchiectatic spaces, and

associated areas of pneumonic consolidation or collapse may be visible.

CT is much more sensitive, and shows thickened, dilated airways

A screening test can be performed in patients suspected of having a

ciliary dysfunction syndrome by measuring the time taken for a small

pellet of saccharin placed in the anterior chamber of the nose to reach

the pharynx, at which point the patient can taste it. This time should not

exceed 20 minutes but is greatly prolonged in patients with ciliary

dysfunction.

Ciliary beat frequency may also be assessed from biopsies taken from the nose.

Structural abnormalities of cilia can be detected by electron microscopy

Management

Physiotherapy

Deep breathing followed by forced expiratory manœuvres (the ‘active cycle of breathing’

technique) helps to move secretions in the dilated bronchi towards the trachea, from

which they can be cleared by vigorous coughing. Devices that increase airway pressure

either by a constant amount (positive expiratory pressure mask) or in an oscillatory

manner (flutter valve)

Antibiotic therapy

For most patients with bronchiectasis, the appropriate antibiotics are the same as those

used in COPD

Surgical treatment

Excision of bronchiectatic areas is only indicated in a small proportion of cases. These

are usually patients in whom the bronchiectasis is confined to a single lobe or segment

on CT.