Asthma 1

Assistant prof.Dr. Ahmed Hussein Jasim

FIBMS (resp),

FIBMS (med)

The chronic inflammation is associated with airway hyper-responsiveness that leads to

recurrent episodes of wheezing, breathlessness, chest tightness and coughing,

particularly at night and in the early morning.

These episodes are usually associated with widespread but variable airflow obstruction

within the lung that is often reversible, either spontaneously or with treatment.

PathophysiologyAirway hyper-reactivity (AHR) – the tendency for airways to narrow

excessively is integral to the diagnosis of asthma and appears to be related to

airway inflammation .The relationship between atopy (the propensity to produce

IgE) and asthma is well established, and in many individuals there is a clear

relationship between sensitisation and allergen exposure, as demonstrated by skin

prick reactivity or elevated serum specific IgE.

Common examples of allergens include house dust mites, pets such as cats and

dogs, pests such as cock-roaches, and fungi. Inhalation of an allergen into the

airway is followed by an early and late-phase broncho-constrictor response.

In cases of aspirin-sensitive asthma, the ingestion of salicylates results in

inhibition of the cyclo-oxygenase enzymes, preferentially shunting the

metabolism of arachidonic acid through the lipoxygenase pathway with

resultant production of the asthmogenic cysteinyl leukotrienes.

In exercise-induced asthma, hyperventilation results in water loss from the

pericellular lining fluid of the respiratory mucosa, which, in turn, triggers

mediator release.

In persistent asthma, is characterised by an influx of numerous inflammatory

cells,

asthma is predominantly characterised by airway eosinophilia, neutrophilic

inflammation predominates in some patients, while, in others, scant

inflammation is observed: so-called ‘pauci-granulocytic’ asthma.

With increasing severity and chronicity of the disease, remodelling of the

airway may occur, leading to fibrosis of the airway wall, fixed narrowing of

the airway and a reduced response to bronchodilator medication.

Clinical features

Typical symptoms include recurrent episodes of wheezing, chest tightness,

breathlessness and cough.

Classical precipitants include exercise, particularly in cold weather, exposure to

airborne allergens or pollutants, and viral upper respiratory tract infections.

Patients with mild intermittent asthma are usually asymptomatic between

exacerbations. Individuals with persistent asthma report ongoing breathlessness

and wheeze, but these are variable, with symptoms fluctuating over the course

of one day, or from day to day or month to month.

Some patients with asthma have a similar inflammatory response in the

upper airway. Careful enquiry should be made as to a history of sinusitis,

sinus headache, a blocked or runny nose, and loss of sense of smell.

In some circumstances, the appearance of asthma is triggered by medications.

Beta-blockers, even when administered topically as eye drops, may induce

broncho spasm, as may aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

(NSAIDs).

The classical aspirin sensitive patient is female and presents in middle age

with asthma, rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps.

Other medications implicated include the oral contraceptive pill, cholinergic agents and

prostaglandin F2α. Betel nuts contain arecoline, which is structurally similar to methacholine and

can aggravate asthma.

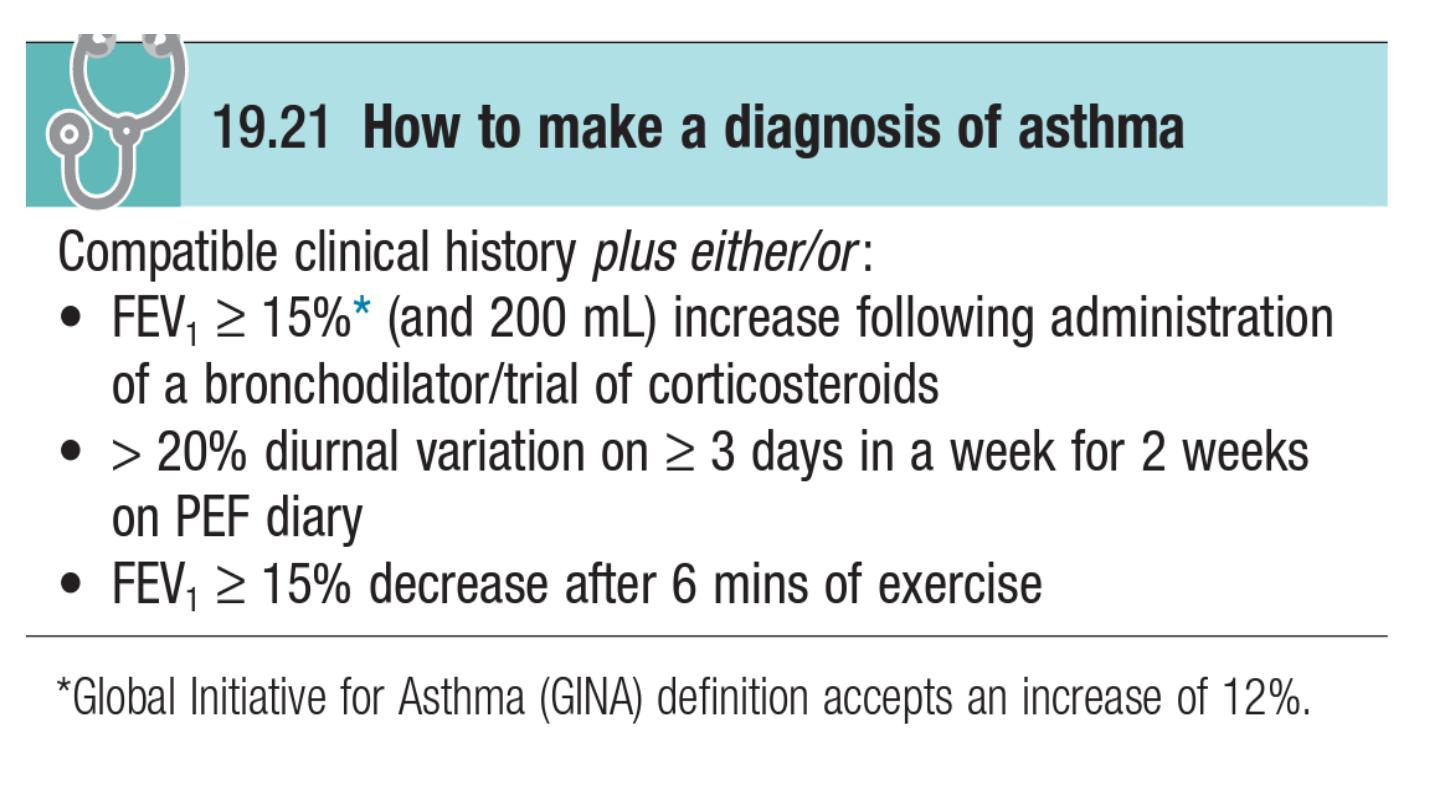

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of asthma is predominantly clinical and based on a characteristic

history.Supportive evidence is provided by the demonstration of variable airflow

obstruction, preferably by using spirometry .to measure FEV1 and VC. This identifies

the obstructive defect, a peak flow meter may be used. Patients should be instructed

to record peak flow readings after rising in the morning and before retiring in the

evening. A diurnal variation in PEF of more than 20% (the lowest values typically

being recorded in the morning) is considered diagnostic. A trial of corticosteroids (e.g.

30 mg daily for 2 weeks) may be useful in establishing the diagnosis, by

demonstrating an improvement in either FEV1 or PEF

.It is not uncommon for

patients whose symptoms are suggestive of asthma to have normal lung

function. In these circumstances, the demonstration of AHR by challenge tests may be

useful to confirm the diagnosis AHR is sensitive but non-specific.

Other investigations

• Measurement of allergic status: the presence of atopy may be demonstrated by skin prick tests. Similar

information may be provided by the measurement of total and allergen-specific IgE. A full blood picture

may show the peripheral blood eosinophilia

.•Radiological examination: chest X-ray appearances are often normal or show hyperinflation of lung

fields. An HRCT scan may be useful to detect bronchiectasis.

• Assessment of eosinophilic airway inflammation: an induced sputum differential eosinophil count of

greater than 2% or exhaled breath nitric oxide concentration (FENO) may support the diagnosis but is

non-specific.

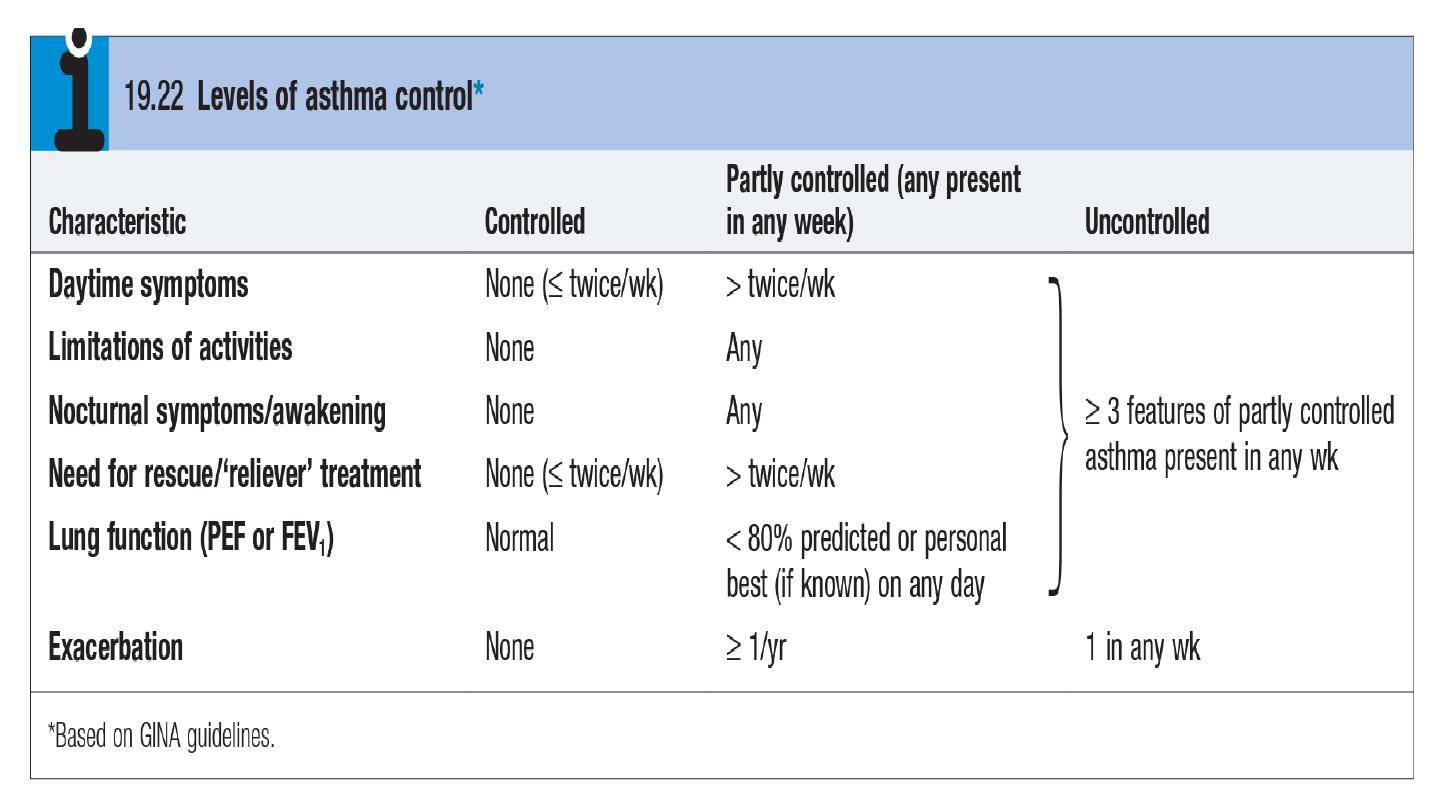

Management

Setting goals

The goal of treatment should be to obtain and maintain complete control , A full explanation of

the nature of the condition, the relationship between symptoms and inflammation, the

importance of key symptoms such as nocturnal waking, the different types of medication, and,

if appropriate, the use of PEF to guide management decisions, should be given.Avoidance of

aggravating factorsThis is particularly important in the management of occupational asthma

but may also be relevant in atopic patients, when removing or reducing exposure to relevant

antigens, such as a pet, may effect improvement. House dust mite exposure may be

minimized by replacing carpets with floorboards and using mite-impermeable

bedding.Smoking cessation is particularly important, as smoking not only encourages

sensitization, but also induces a relative corticosteroid resistance in the airway.

TREATMENT

Bronchodilators

The most common bronchodilator agents used for treatment of asthma are the

sympathomimetic agents, which act on β2 receptors to activate adenylate cyclase and

increase intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP).

The second class of bronchodilator agents, the methylxanthines, is used much less frequently than β2

agonists. Theophylline, the prototype of this class, is generally believed to act by inhibiting the enzyme

phosphodiesterase (PDE), which normally is responsible for metabolic degradation of cAMP. When

degradation is inhibited, the levels of cAMP in smooth muscle and mast cells increase, resulting again

in broncho-dilation and decreased mediator release from mast cells.

The third class of bronchodilator agents, also used less frequently than β2 agonists in asthma

patients, consists of drugs that have an anticholinergic action. Anticholinergic agents dilate

bronchial smooth muscle by decreasing bronchoconstrictor cholinergic tone to airways.

Ipratropium, available as an aerosol for inhalation, is the primary short-acting example of this

class of agents.

Anti inflammatory drugs

the second major category of drugs used to treat asthma has included anti inflammatory

agents: corticosteroids, disodium cromoglycate (cromolyn), and nedocromil. They suppress the

inflammatory response by decreasing the number of eosinophils and lymphocytes infiltrating

the airway and decrease production of a number of inflammatory mediators

Agents with Specific Targeted Action

Specific agents that modify leukotrienes or leukotriene pathways include zafirlukast and

montelukast, which antagonize the action of LTD4 at its receptor, and zileuton, which inhibits

the enzyme 5-lipoxygenase and thus limits leukotriene production. On the basis of their mode

of action, drugs that either block leukotriene synthesis or antagonize their action have a

particularly important role in patients who are sensitive to aspirin or other NSAIDs.

The newest agent for treatment of asthma is omalizumab, a monoclonal antibody to IgE. On

the basis of the principle that IgE is an important component of the pathobiology of allergic

asthma, the drug was developed to prevent the binding of IgE to receptors on mast cells.

Bronchial Thermoplasty

Bronchial thermoplasty, a new procedure performed via a flexible bronchoscope, thermal energy

is delivered to the airways in an effort to reduce airway smooth muscle mass. Studies indicate

that the procedure can produce sustained benefit in patients with moderate and severe asthma,

but experience is limited.

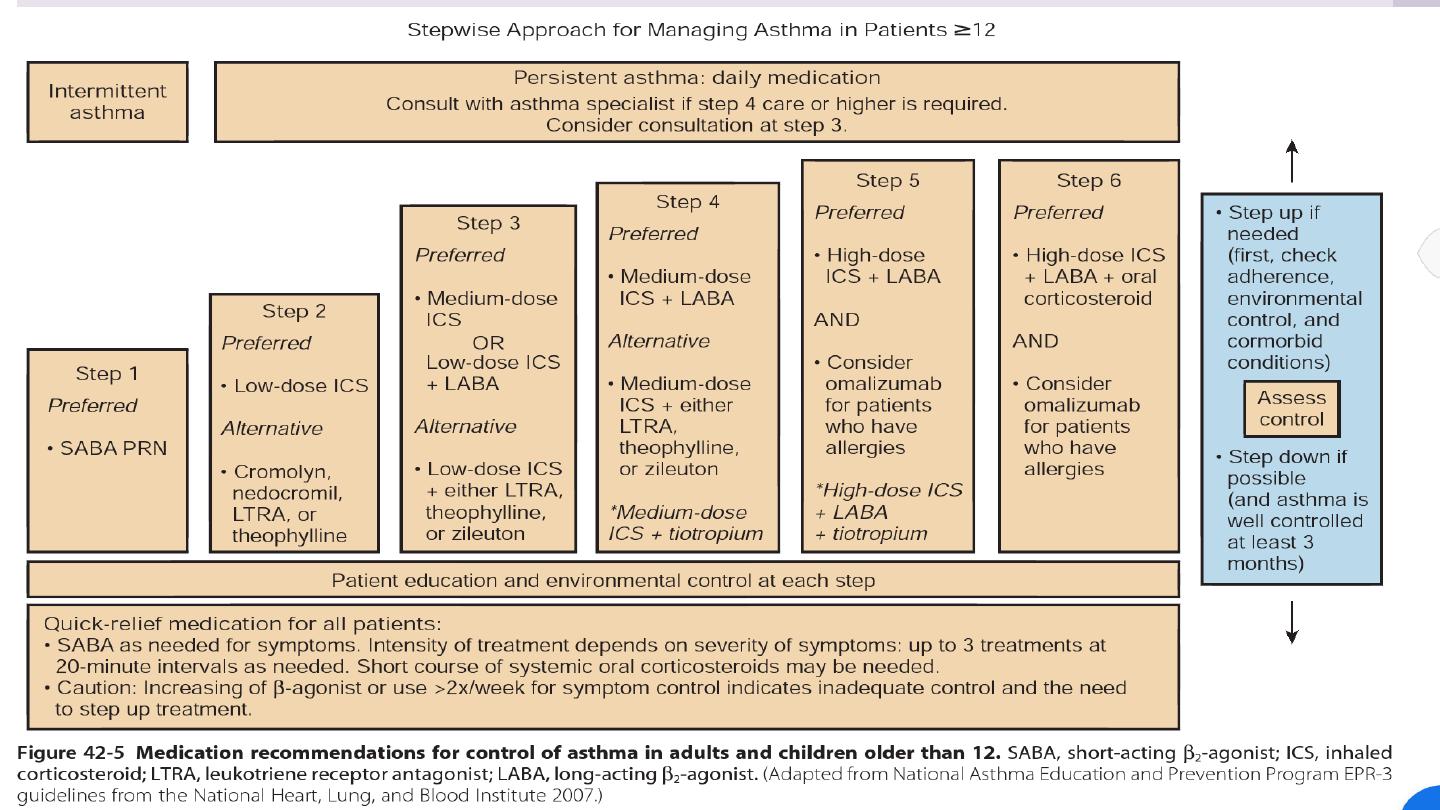

The stepwise approach to the management of asthma

Glucocorticoids are thought to bind to a cytoplasmic receptor present in nearly all cell types.

After the receptor binds to its glucocorticoid ligand, it moves to the cell nucleus, where it

interacts with transcription factors such as activator protein (AP)-1 and nuclear factor (NF)-κB,

which regulate transcription of other target genes.

Step 3: Add-on therapy

Step 4: Poor control on moderate dose of inhaled steroid and add-on therapy: addition of a

fourth drug

Step 5: Continuous or frequent use of oral steroids

Step-down therapy

Once asthma control is established, the dose of inhaled (or oral) corticosteroid should be

titrated to the lowest dose at which effective control of asthma is maintained. Decreasing the

dose of ICS by around 25–50% every 3 months is a reasonable strategy for most patients.

Step 2: Introduction of regular preventer therapy

• anti-inflammatory therapy (preferably inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), such as beclometasone,

budesonide (BUD), fluticasone or ciclesonide) should be started in addition to inhaled β2-agonists

taken on an as-required basis for any patient who:• has experienced an exacerbation of asthma in

the last 2 years . .

uses inhaled β2-agonists three times a week or more• reports symptoms three

times a week or more• is awakened by asthma one night per week.

Step 1: Occasional use of inhaled short-acting β2-adrenoreceptor agonist bronchodilators

patients with mild intermittent asthma (symptoms less than once a week for 3 months and fewer than

two nocturnal episodes per month), it is usually sufficient to prescribe an inhaled short-acting β2-

agonist, such as salbutamol or terbutaline, to be used as required.

Exacerbations of asthma

The course of asthma may be punctuated by exacerbations with increased symptoms,

deterioration in lung function, and an increase in airway inflammation.

Exacerbations are most commonly precipitated by viral infections, but moulds (Alternaria

and Cladosporium), pollens (particularly following thunderstorms) and air pollution are

also implicated.

Management of mild to moderate exacerbations

Short courses of ‘rescue’ oral cortico steroids (prednisolone 30–60 mg daily) therefore

are often required to regain control.

Indications for ‘rescue’ courses include: • symptoms and PEF progressively worsening day

by day, with a fall of PEF below 60% of the patient’s personal best recording

• onset or worsening of sleep disturbance by asthma

• persistence of morning symptoms until midday

• progressively diminishing response to an inhaled bronchodilator

• symptoms sufficiently severe to require treatment with nebulised or injected

bronchodilators.

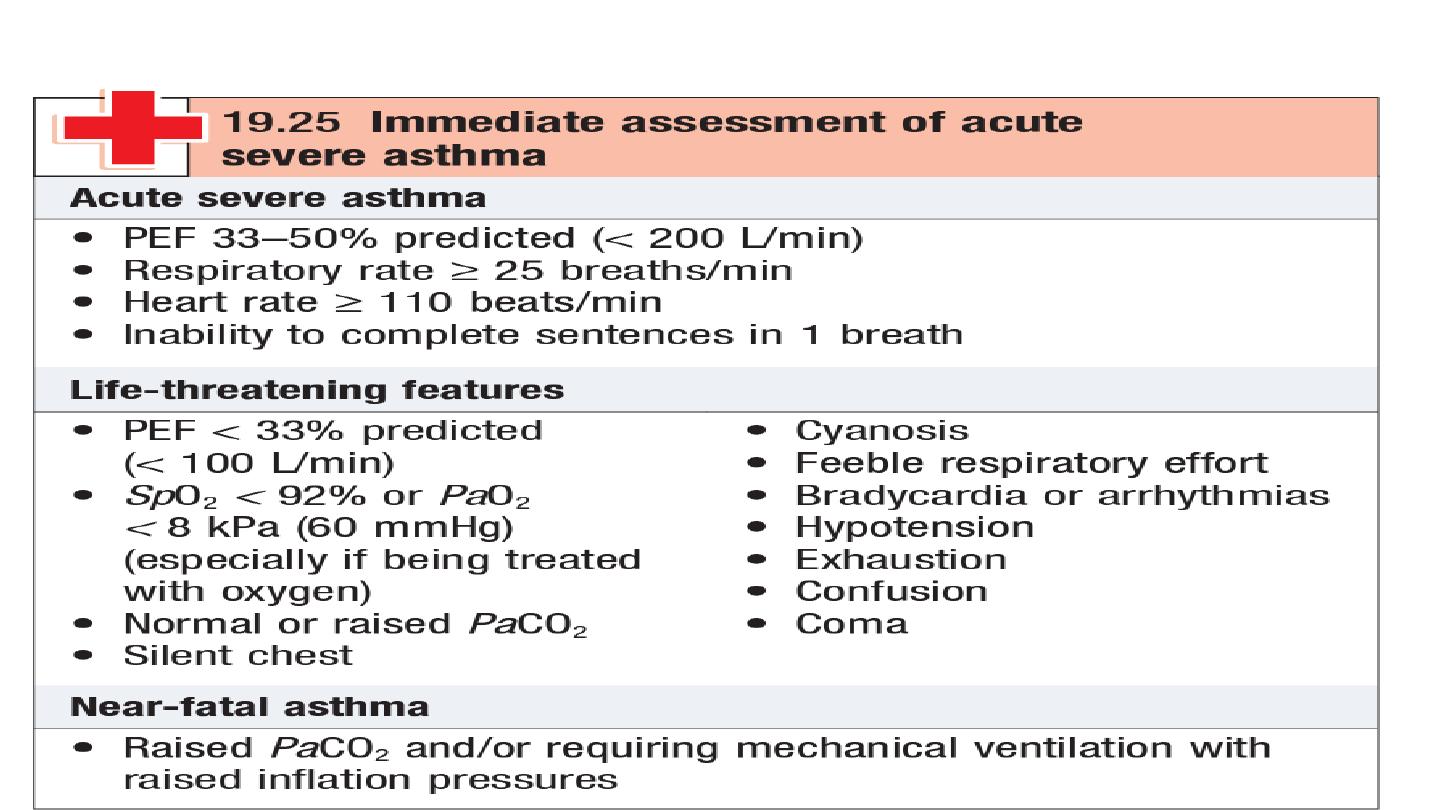

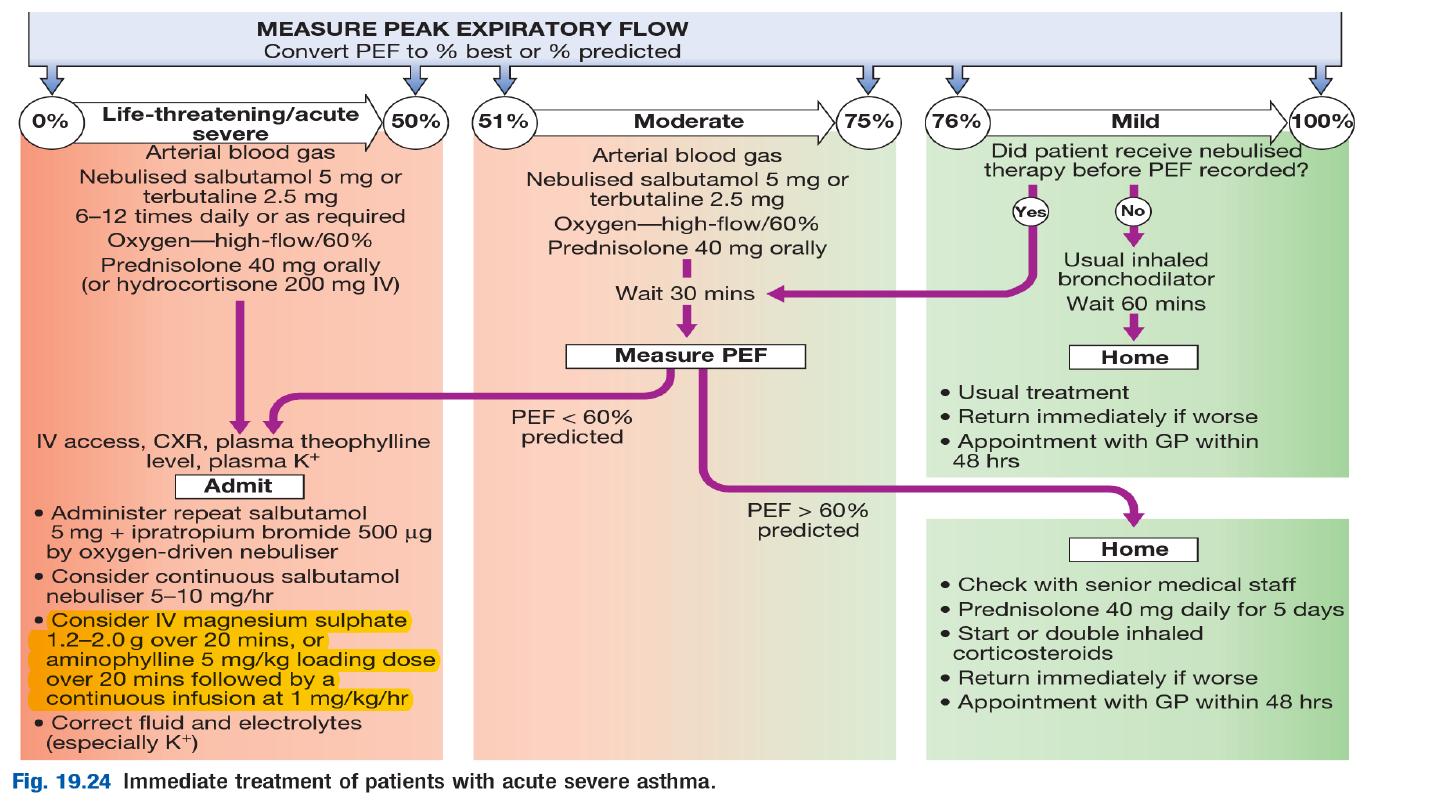

Management of acute severe asthma

If patients fail to improve, a number of further options may be

considered

. Intravenous magnesium may provide additional

bronchodilatation in patients whose presenting PEF is below 30%

predicted. Some patients appear to benefit from the use of intravenous

aminophylline but cardiac monitoring is recommended.

PEF should be recorded every 15–30 minutes and then every 4–6 hours.

Pulse oximetry should ensure that SaO2 remains above 92%, but

repeat

arterial blood gases are necessary if the initial PaCO2 measurements

were normal or raised, the PaO2 was below 8 kPa (60 mmHg), or the

patient deteriorates.

Prior to discharge, patients should be stable on discharge medication (nebulised

therapy should have been discontinued for at least 24 hours) and the PEF should have

reached 75% of predicted or personal best.