HYPERTENSION

THE SILENT KILLER

introduction:

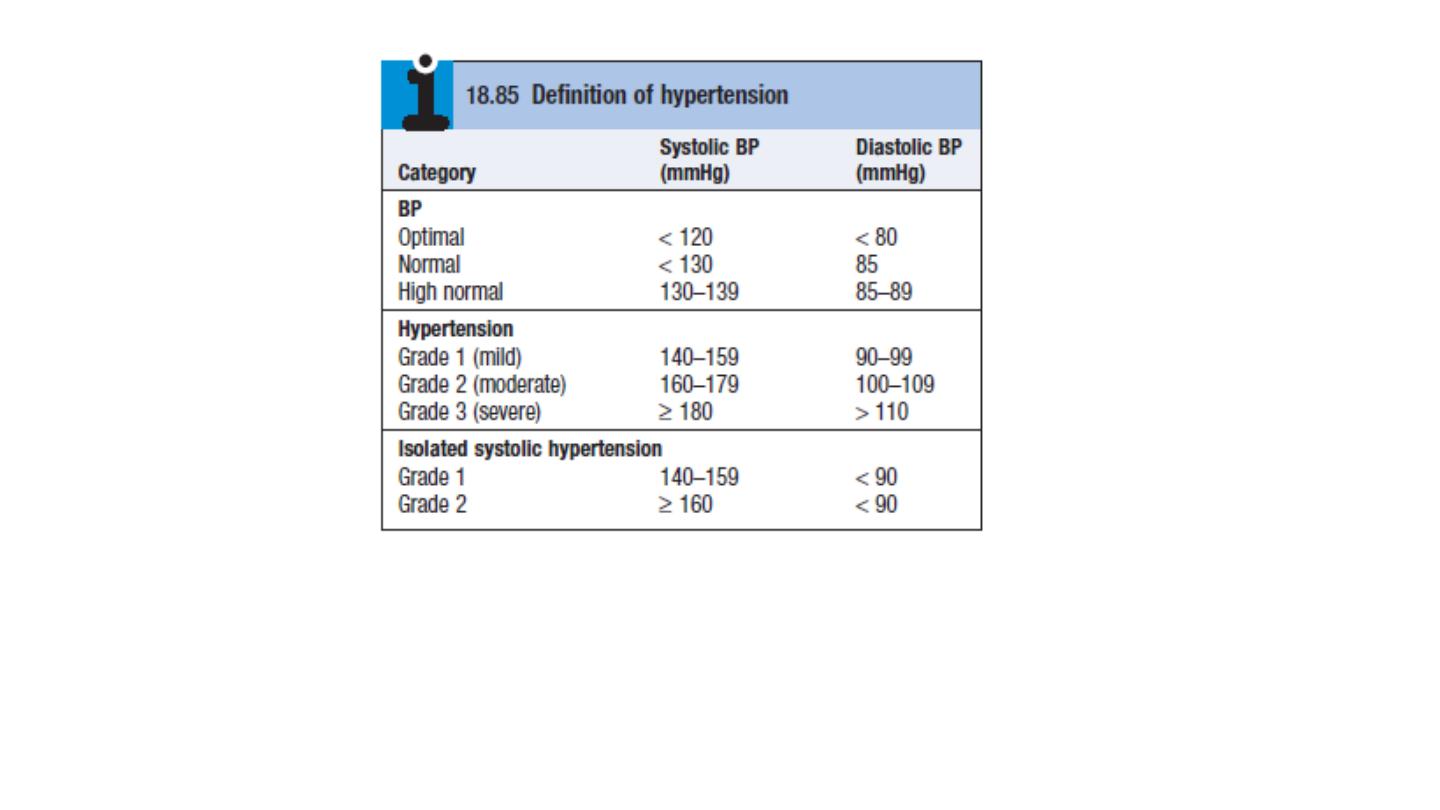

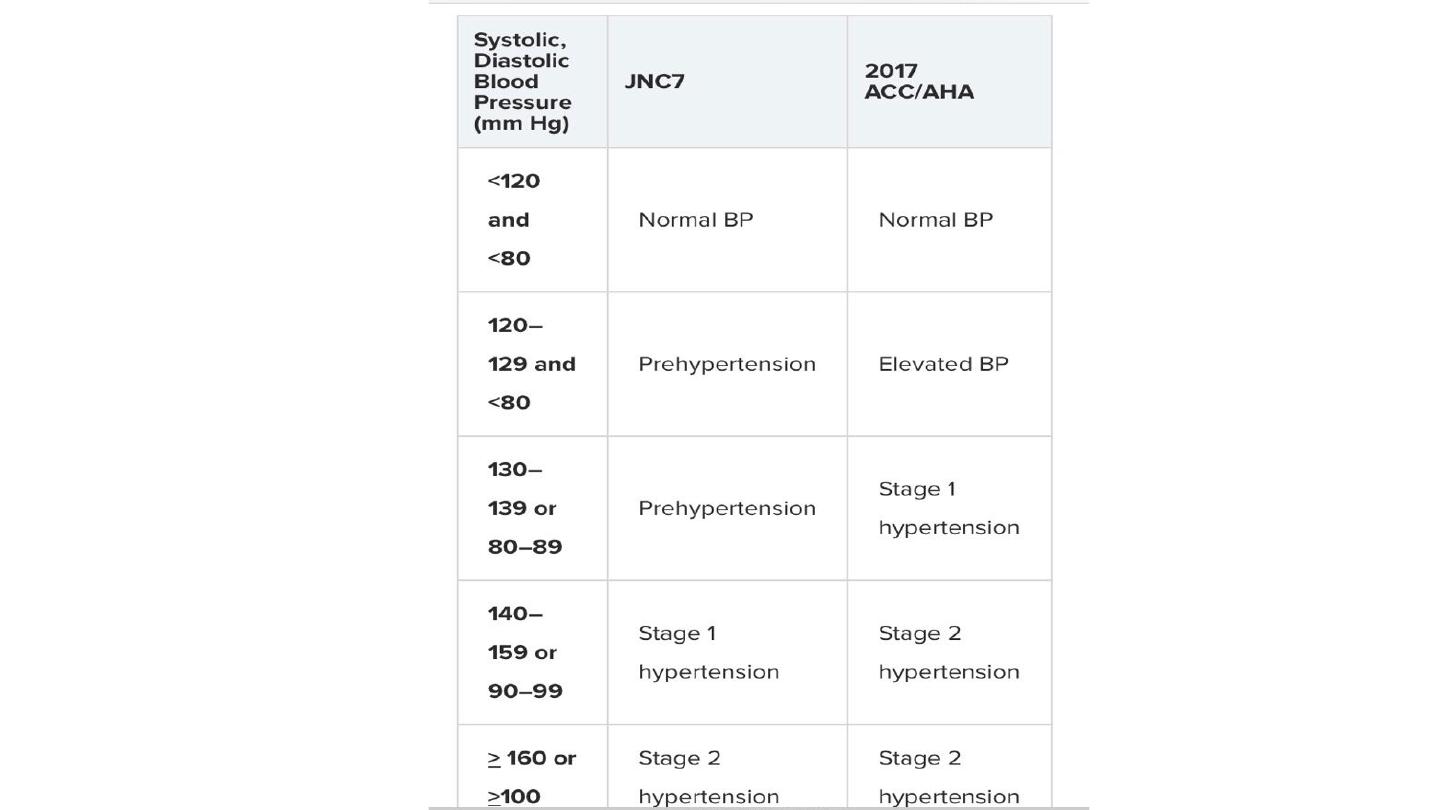

Blood pressure values are continuous variables, so the definition of

hypertension is arbitrary. Systemic BP rises with age.

incidence of cardiovascular disease (particularly stroke and coronary

artery disease) is closely related to average BP at all ages, even when

BP readings are within the so-called ‘normal range.

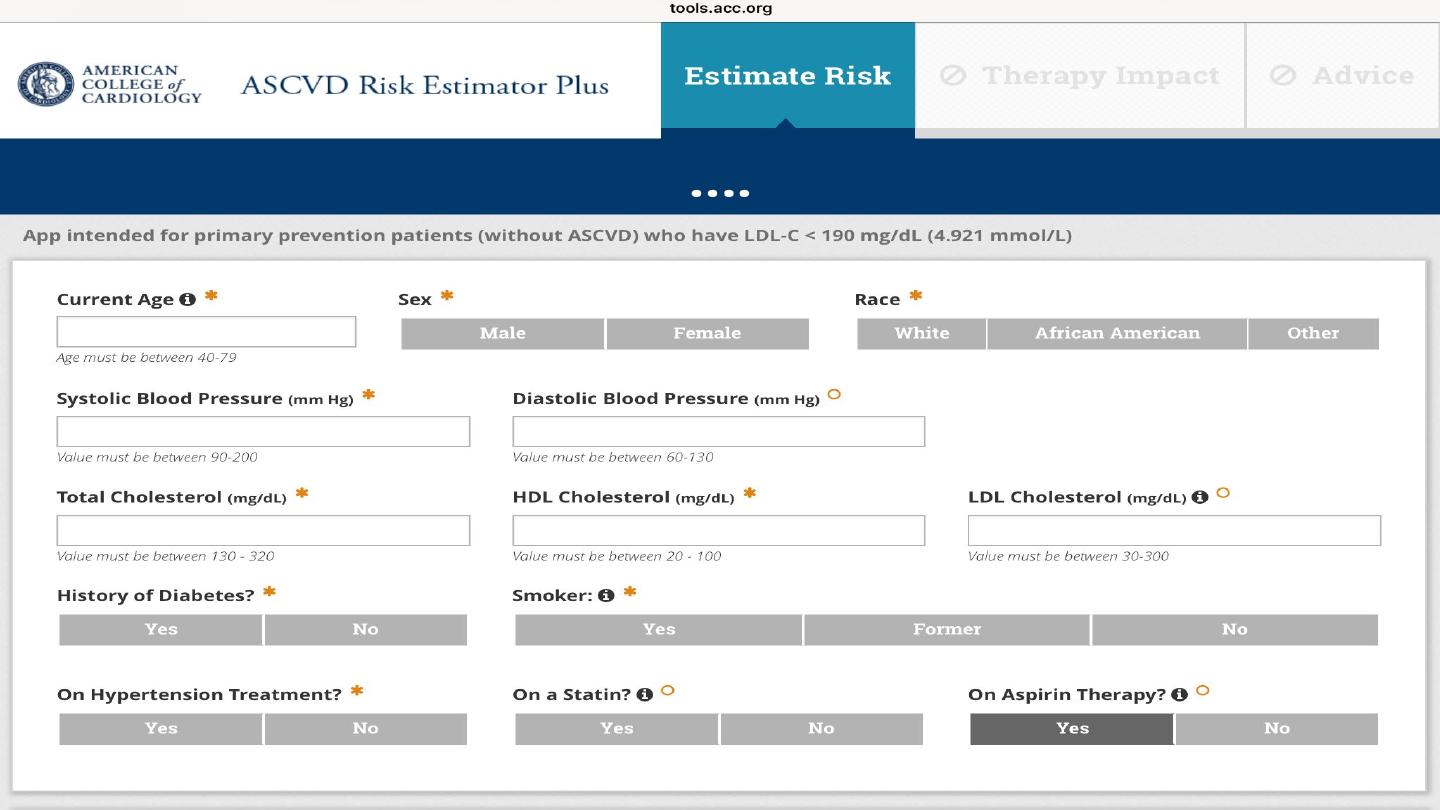

The cardiovascular risks associated with BP depend upon the

combination of risk factors in an individual, such as age, gender, weight,

physical activity, smoking, family history, serum cholesterol, diabetes

mellitus and pre-existing vascular disease

Etiology:

Primary , essential HPT account for 95%, no obvious cause can be

identified. The pathogenesis is not clearly understood. Many

factors may contribute to its development, including renal

dysfunction, peripheral resistance vessel tone, endothelial

dysfunction, autonomic tone, insulin resistance and neurohumoral

factors.

Hypertension is more common in some ethnic groups, particularly

African Americans and Japanese

, and approximately 40–60% is

explained by genetic factors.

Important environmental factors include a high salt intake, heavy

consumption of alcohol, obesity, lack of exercise and impaired

intrauterine growth. There is little evidence that ‘stress’ causes

hypertension

Hypertension is predominantly an asymptomatic condition and the

diagnosis is usually made at routine examination or when a

complication arises.

A BP check is advisable every 5 years in adults.

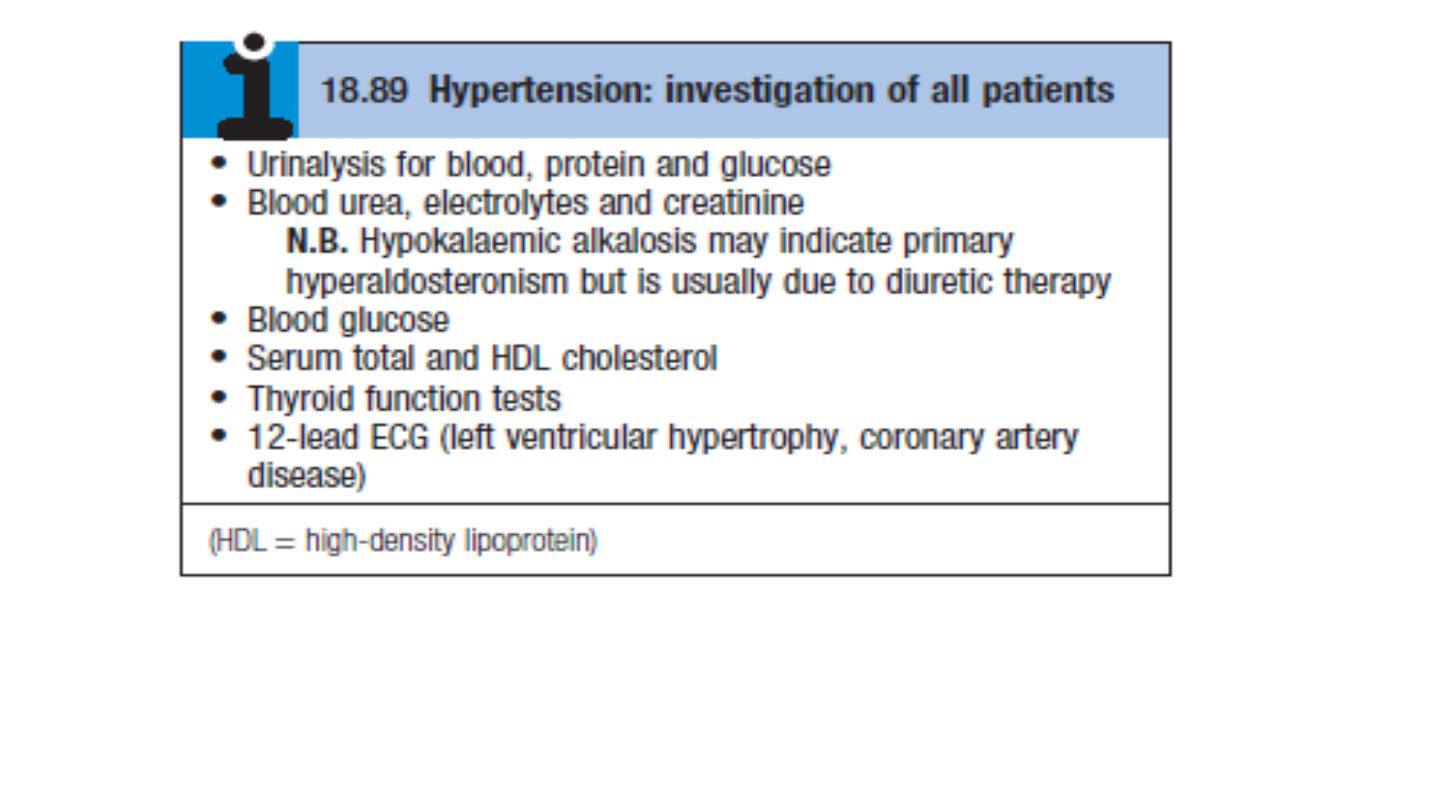

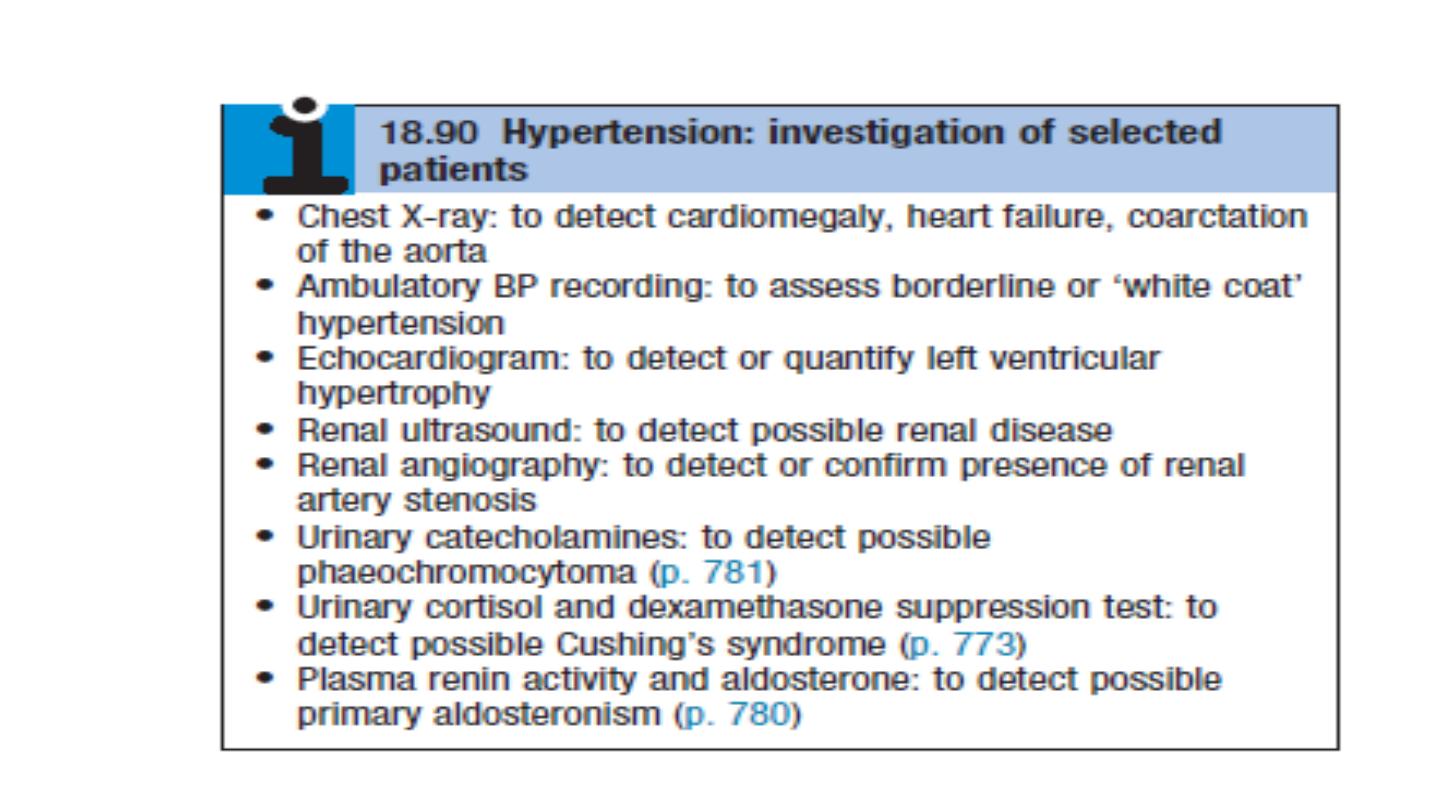

Initial evaluation

1. Accurate measurement of blood pressure

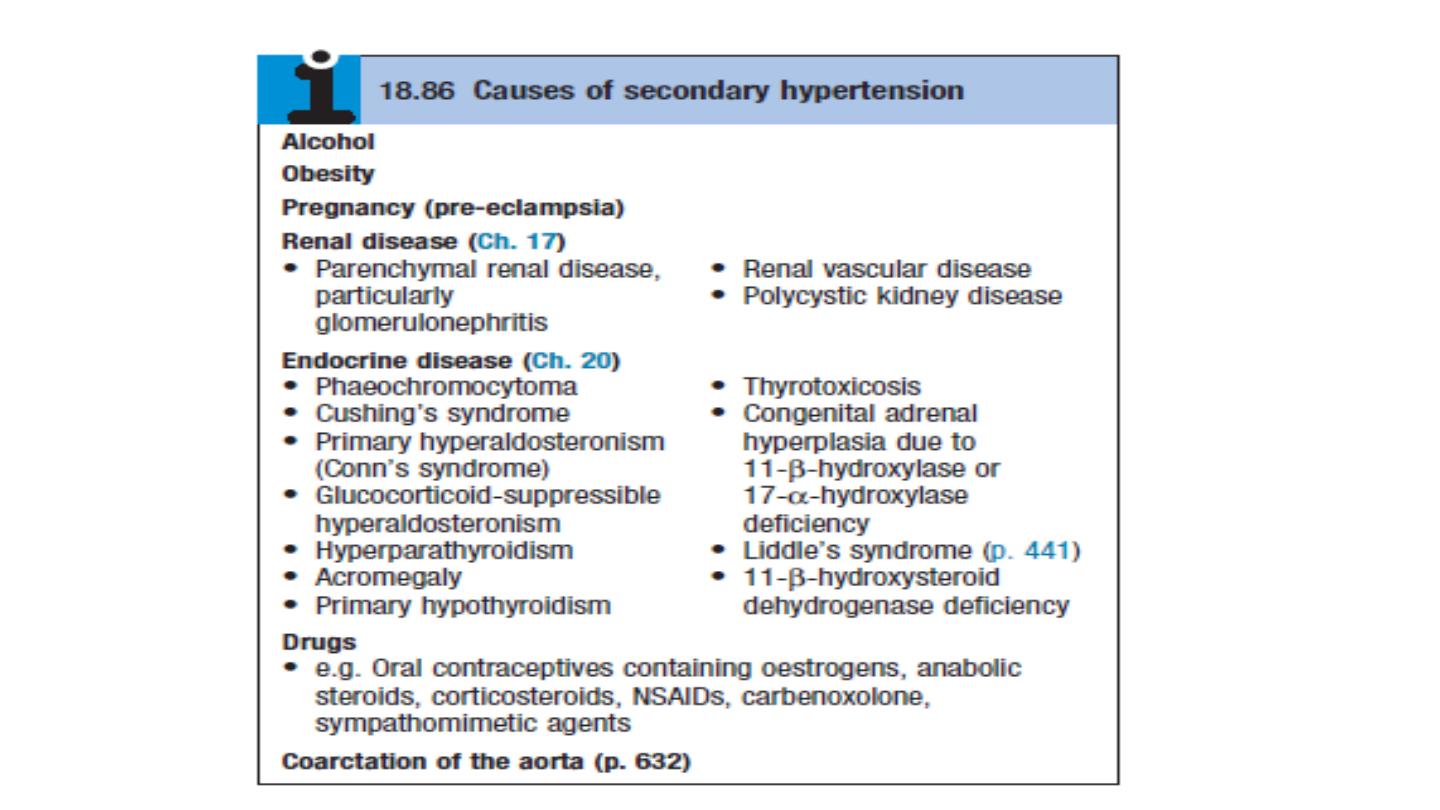

2. Identify possible secondary causes

3. Assess comorbidities and other risk factors

4. Detect any complication

This can be assessed by:

History

Physical examination

investigation

Measurement of blood pressure

Antihypertensive once started → life long treatment

Tight cuff → high pressure readings

Large cuff → low pressure readings

White coat hypertension:

Exercise, anxiety, discomfort and unfamiliar surroundings can all lead to

a transient rise in BP. as many as 20% of patients with apparent

hypertension in the clinic may have a normal BP when it is recorded by

automated devices used at home. The risk of cardiovascular disease in

these patients is less than that in patients with sustained hypertension

but greater than that in normotensive subjects.

ambulatory BP measurements obtained over 24 hours or longer

provides a better profile than a limited number of clinic readings and

correlates more closely with evidence of target organ damage than

casual BP measurements.

Home or ambulatory BP measurements are particularly helpful in

patients with unusually labile BP, those with refractory hypertension,

those who may have symptomatic hypotension, and those in whom

white coat hypertension is suspected.

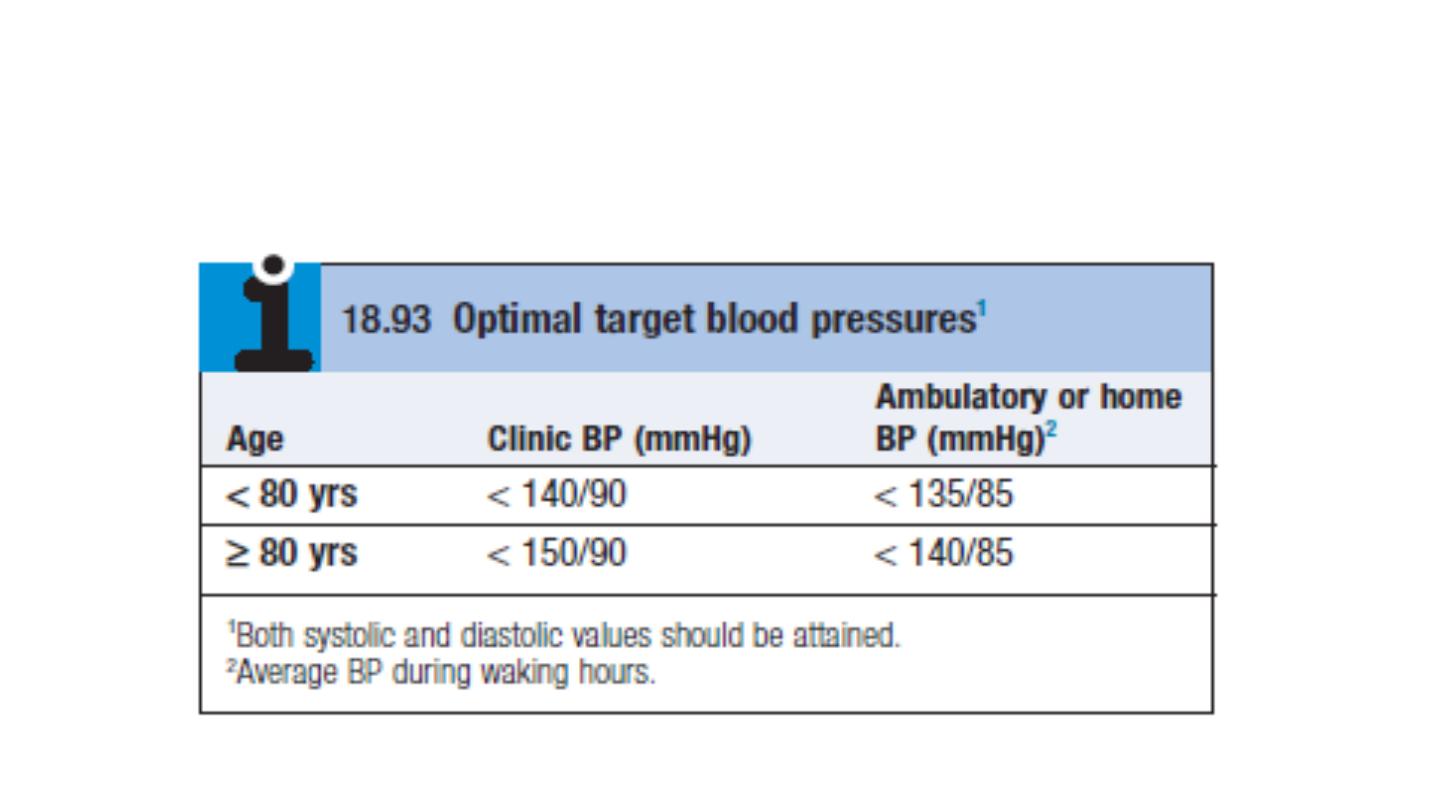

However, treatment thresholds and targets must be adjusted

downwards because ambulatory BP readings are systematically lower

(approximately 12/7mmHg) than clinic measurements.

History

Family history, lifestyle (exercise, salt intake, smoking habit) and other risk

factors should be recorded.

A careful history will identify those patients with drug- or alcohol-induced

hypertension and may elicit the symptoms of other causes of secondary

hypertension such as phaeochromocytoma (paroxysmal headache,

palpitation and sweating or complications such as coronary artery disease

(e.g. angina, breathlessness).

EXAMINATION

Radio-femoral delay (coarctation of the aorta), enlarged kidneys

(polycystic kidney disease), abdominal bruits (renal artery stenosis) and

the characteristic facies and habitus of Cushing’s syndrome are all

examples of physical signs that may help to identify causes of

secondary hypertension .

Examination may also reveal features of important risk factors such as

central obesity and hyperlipidaemia (tendon xanthomas etc.).

Most abnormal signs are due to the complications of hypertension.

Non-specific findings may include left ventricular hypertrophy (apical

heave), accentuation of the aortic component of the second heart

sound, and a fourth heart sound. The optic fundi are often abnormal

and there may be evidence of generalised atheroma or specific

complications such as aortic aneurysm or peripheral vascular disease.

Target organ damage

1. Blood vessels

In larger arteries (> 1 mm in diameter), the internal elastic lamina is

thickened, smooth muscle is hypertrophied and fibrous tissue is

deposited. The vessels dilate and become tortuous, and their walls

become less compliant.

In smaller arteries (< 1 mm), hyaline arteriosclerosis occurs in the wall,

the lumen narrows and aneurysms may develop.

Hypertension is a major risk factor in the pathogenesis of aortic

aneurysm and aortic dissection.

Wide spread atherosclerosis

2. CNS

Stroke:

Stroke is a common complication of hypertension and

may be due to cerebral haemorrhage or infarction. Carotid

atheroma and transient ischaemic attacks are more common

in hypertensive patients. Subarachnoid haemorrhage is also

associated with hypertension

Hypertensive encephalopathy

is a rare condition characterised by

high BP and neurological symptoms, including transient disturbances of

speech or vision, paraesthesiae, disorientation, fits and loss of

consciousness. Papilloedema is common. A CT scan of the brain often

shows haemorrhage in and around the basal ganglia; however, the

neurological deficit is usually reversible if the hypertension is properly

controlled.

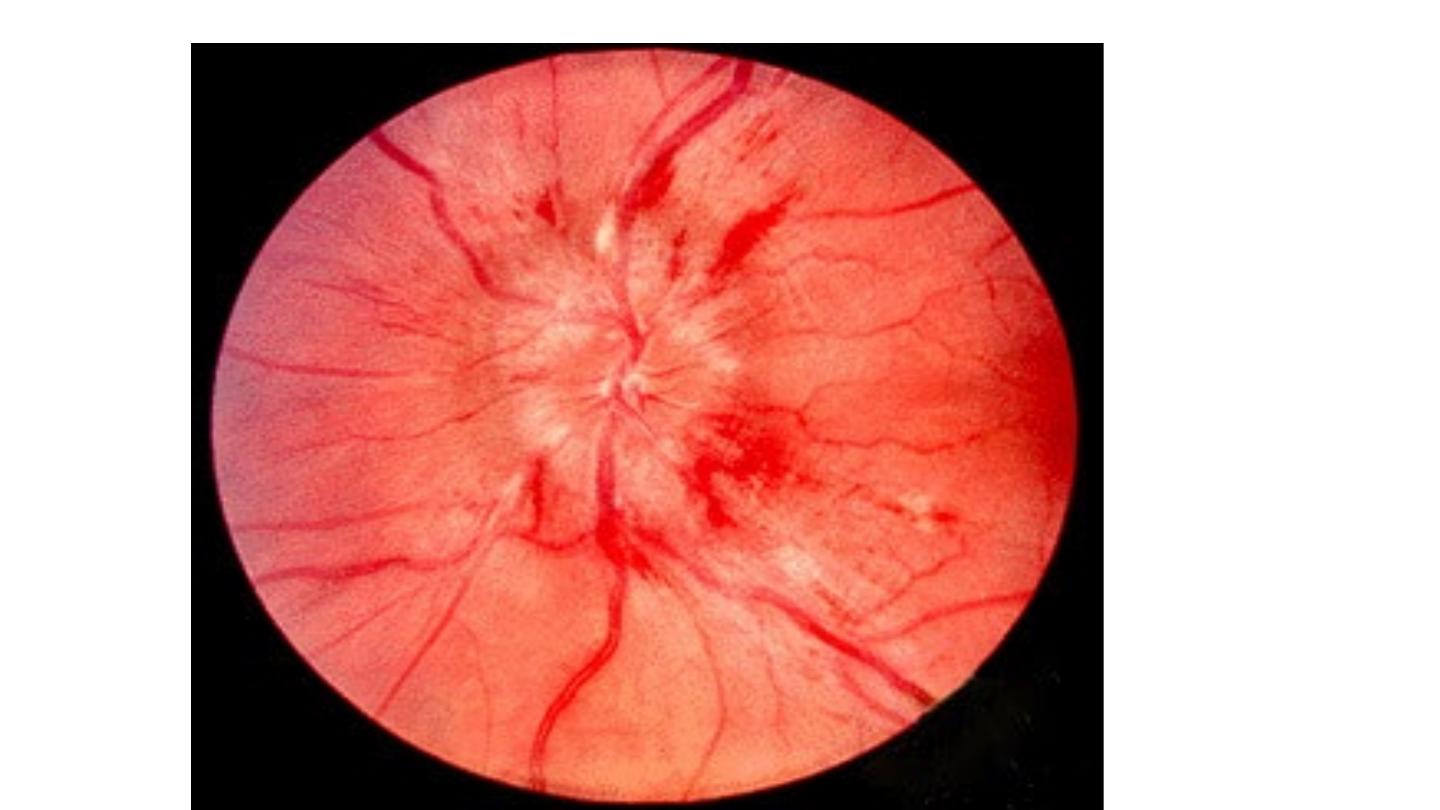

3. retina

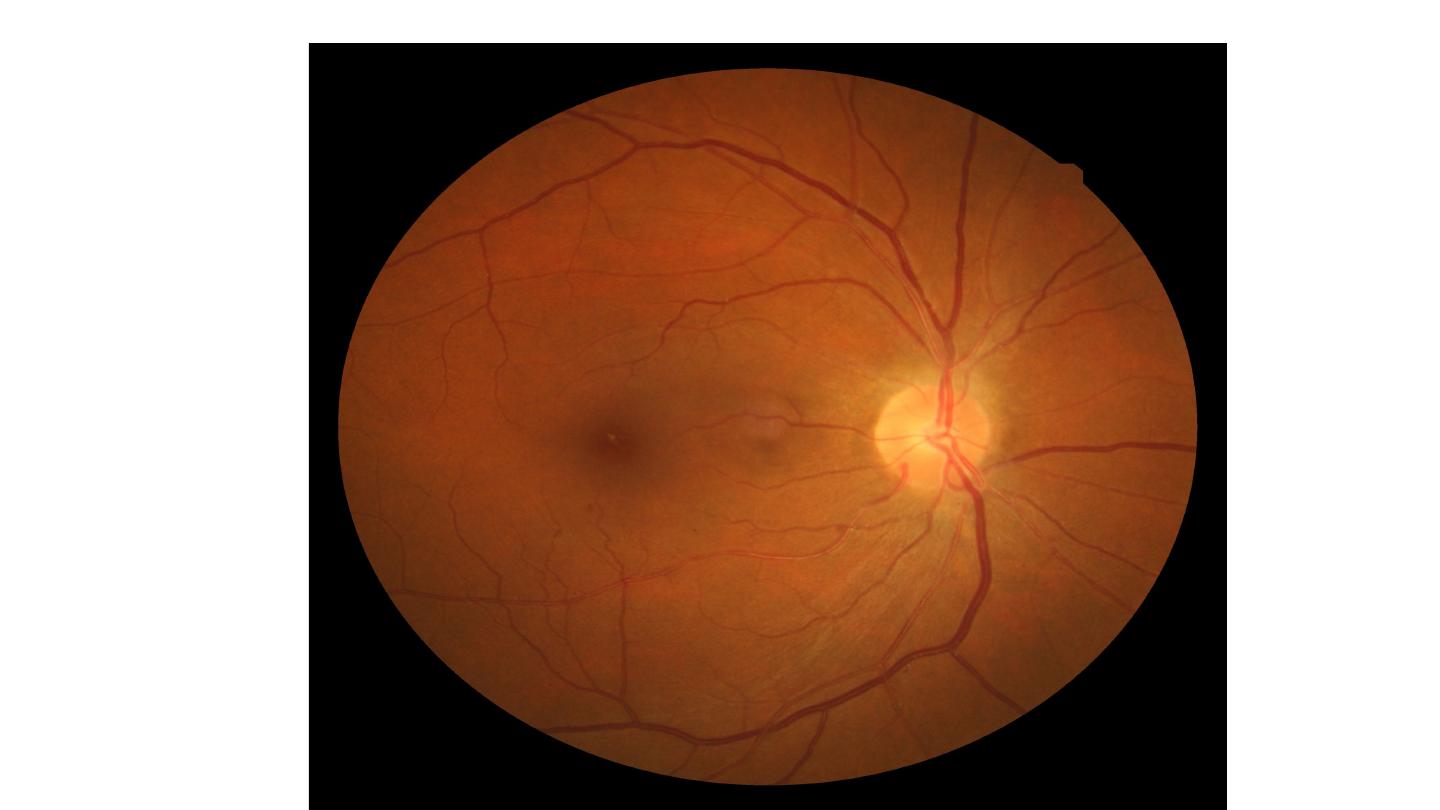

Retina The optic fundi reveal a gradation of changes linked to the

severity of hypertension; fundoscopy can, therefore, provide an

indication of the arteriolar damage occurring elsewhere ‘Cotton wool’

exudates are associated with retinal ischaemia or infarction, and fade in

a few weeks . ‘Hard’ exudates (small, white, dense deposits of lipid)

and microaneurysms (‘dot’ haemorrhages) are more characteristic of

diabetic retinopathy . Hypertension is also associated with central

retinal vein thrombosis

4. Heart

The excess cardiac mortality and morbidity associated with hypertension are

largely due to a higher incidence of coronary artery disease. High BP places a

pressure load on the heart and may lead to left ventricular hypertrophy with

a forceful apex beat and fourth heart sound. ECG or echocardiographic

evidence of left ventricular hypertrophy is highly predictive of cardiovascular

complications and therefore particularly useful in risk assessment. Atrial

fibrillation is common and may be due to diastolic dysfunction caused by left

ventricular hypertrophy or the effects of coronary artery disease. Severe

hypertension can cause left ventricular failure in the absence of coronary

artery disease, particularly when renal function, and therefore sodium

excretion, is impaired.

5. Kidneys

Long-standing hypertension may cause proteinuria and progressive

renal failure by damaging the renal vasculature.

‘Malignant’ or ‘accelerated’ phase hypertension

characterised by accelerated microvascular damage with necrosis in the

walls of small arteries and arterioles (‘fibrinoid necrosis’) and by

intravascular thrombosis.

The diagnosis is based on evidence of high BP and rapidly progressive

end organ damage, such as retinopathy (grade 3 or 4), renal

dysfunction (especially proteinuria) and/or hypertensive

encephalopathy . Left ventricular failure may occur and, if this is

untreated, death occurs within months.

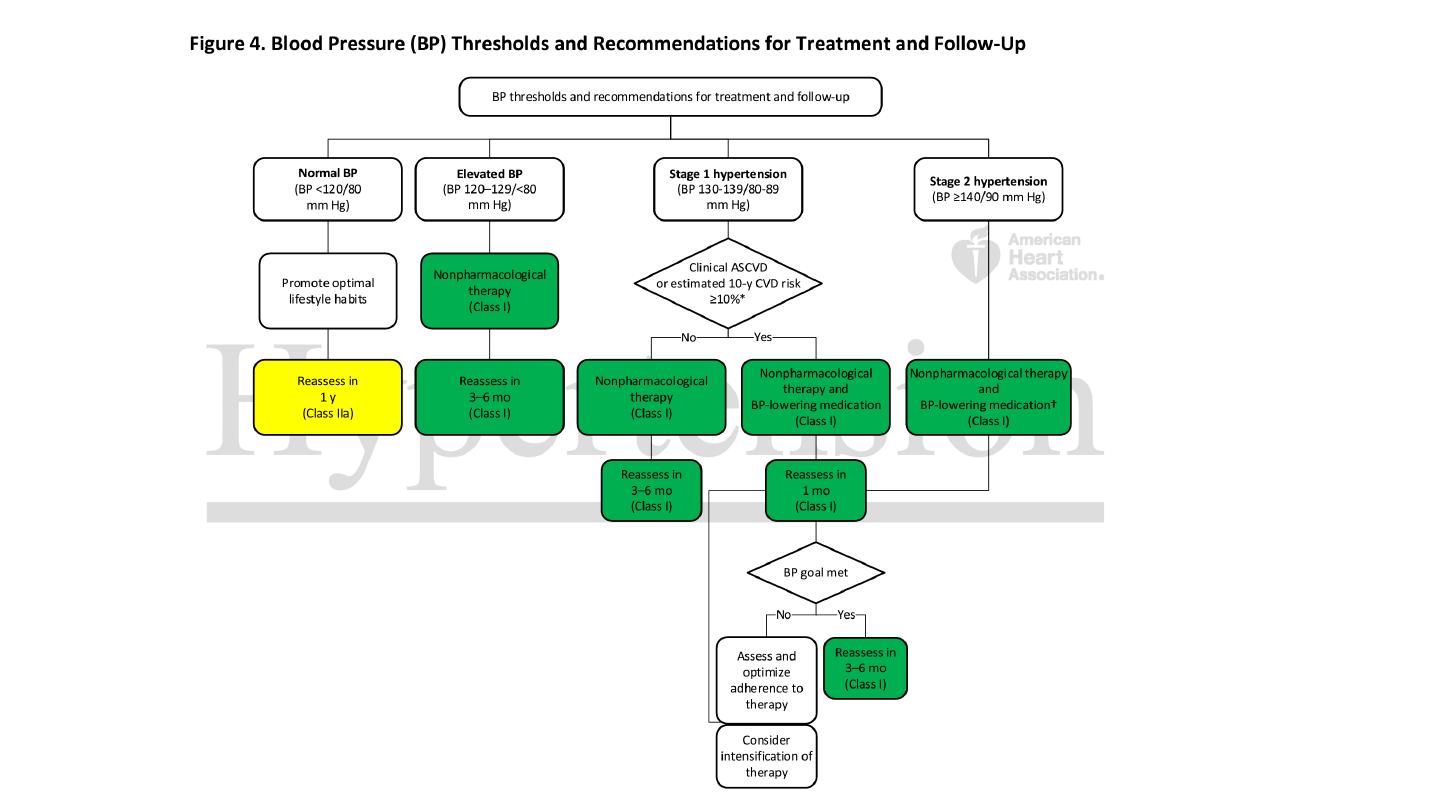

Threshold for intervention

Systolic BP and diastolic BP are both powerful predictors of

cardiovascular risk.

HPT IN ELDERLY

Prevalence: affects more than half of all people over the age of 60 yrs

(including isolated systolic hypertension).

Risks: hypertension is the most important risk factor for MI, heart failure

and stroke in older people.

Benefit of treatment: absolute benefit from therapy is greatest in older

people (at least up to age 80 yrs).

Target BP: similar to that for younger patients.

Tolerance of treatment: antihypertensives are tolerated as well as in

younger patients.

Drug of choice: low-dose thiazides but, in the presence of coexistent disease

(e.g. gout, diabetes), other agents may be more appropriate.

Management

The sole objective of antihypertensive therapy is to reduce the

incidence of adverse cardiovascular events, particularly coronary

artery disease, stroke and heart failure.

The relative benefit of antihypertensive therapy (approximately

30% reduction in risk of stroke and 20% reduction in risk of

coronary heart disease) is similar in all patient groups, so the

absolute benefit of treatment (total number of events

prevented) is greatest in those at highest risk.

Threshold for intervention

Systolic BP and diastolic BP are both powerful predictors of

cardiovascular risk. The British Hypertension Society

management guidelines therefore utilise both readings, and

treatment should be initiated if they exceed the given threshold

Diabetes and established cardiovascular at particular higher risk, so the

threshold for initiation of therapy is lower.

Patients taking antihypertensive therapy require follow-up at 3 monthly

intervals to monitor BP, minimize side-effects and reinforce lifestyle

advice.

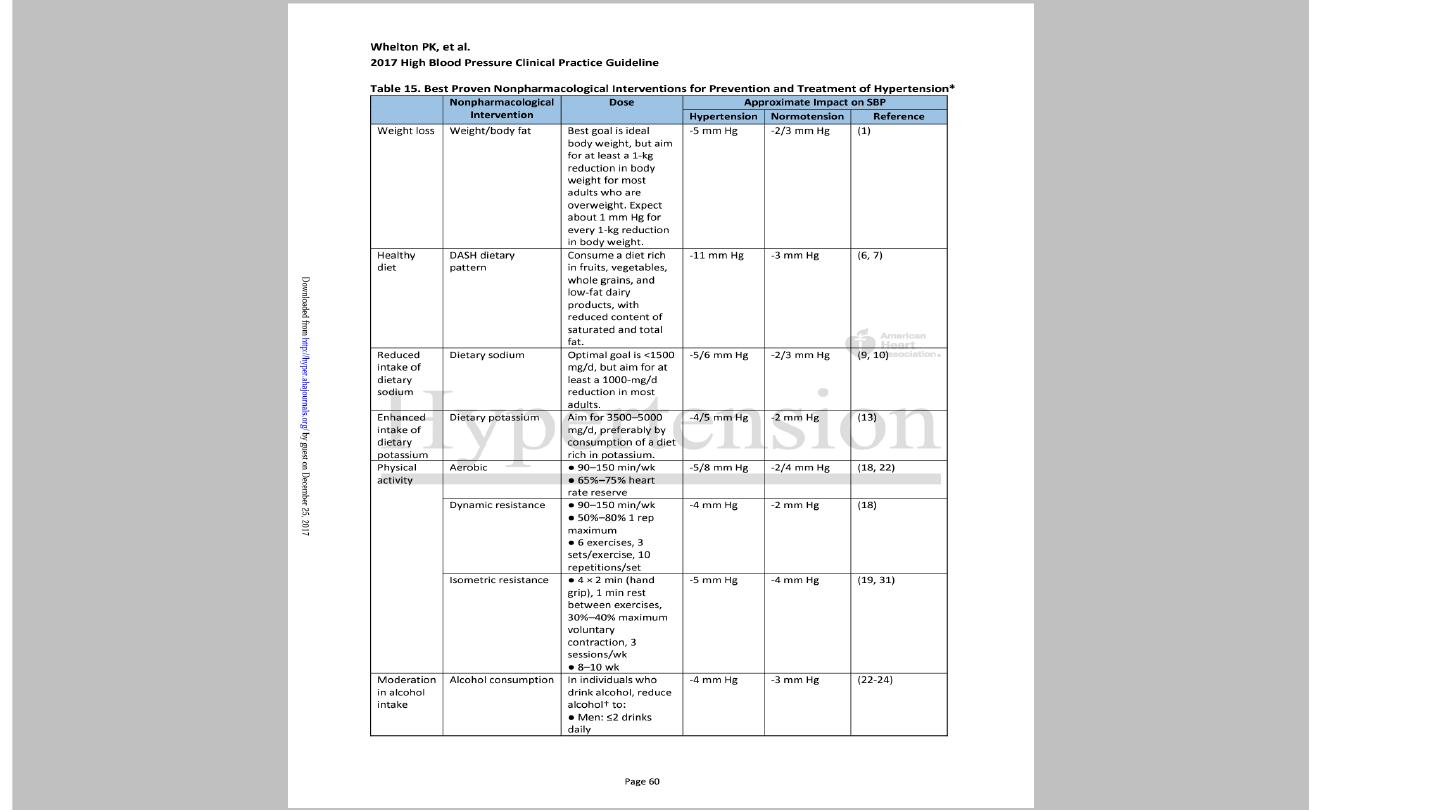

Non drug therapy

Correcting obesity, reducing alcohol intake, restricting salt intake,

taking regular physical exercise and increasing consumption of fruit

and vegetables can all lower BP.

Moreover, quitting smoking, eating oily fish and adopting a diet that is

low in saturated fat may produce further reductions in cardiovascular

risk.

Antihypertensive drugs

Diuretics

Thiazide :

The mechanism of action of these drugs is incompletely understood and it may take up to a

month for the maximum effect to be observed.

e.g Bendroflumethiazide 2.5 mg, Hydrochlorthalidone 50 mg, indapamide 1.5 mg.

S.E : hypokalemia, hyperyrecemia ( can cause gout), hyprglycemia, hypertryglycemia

Loop diuretics

: used as antihypertensive in cases with CRF, GFR less than 30 ml/kg/min

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors:

Angiotensin l converted via ACE to angiotensin ll which cause

vasoconstriction and Stimulate the release of aldosterone from adrenals.

Blocking this pathway result in hypotensive effect.

ACE inhibitors should be used with particular care in patients with impaired

renal function or renal artery stenosis because they can reduce the filtration

pressure in the glomeruli and precipitate renal failure.

Electrolyte should be checked 1 to 2 weeks after initiation of therapy up to

30 % woresning in renal function is accepted, more woresning indicate

stopping ACE inhibitors.

e.g Captopril , enalopril, lisinporil, ramipril, perindopril.

S.E: Dry cough 15 %, angioedema 1 %, hyperkalemia, rash, renal

dysfunction, Neutropenia(captopril)

•

Bradykinin is inflammatory mediators which promote vasodilatation,

degraded by ACE, ACE inhibitors result in accumulation of bradykinin

which give additional antihypetensive effect.

•

Bradykinin is the cause of ACE inhibitors dry cough.

•

ACE inhibtors induced dry cough is indication to stop ACE I hibitors

and to swich to ARB

ARB: angiotensin receptor blockers

e.g: Losartan, Valsartan, telmisartan, candesartan, irbesartan.

Block angiotensin 2 receptor.

Combination of ACE and ARB has no additional antihypertensive effect ,

carry high risk of hyperkalemia and should be avoided.

ARB causing No dry cough, no angioedema, but share the same side

effect with ACE inhibitors Hyperkalemia and renal dysfunction.

Calcium channel antagonists

Dihyropyridine: Nifedipine, felodipine, amlodipine

Non dihydropidine : diltiazim, verapamil

S.E: Flushing , leg edema, effect on HR ( tachycardia with

dihydropyridine and bradycardia with non dihydropyridine)

Constipation

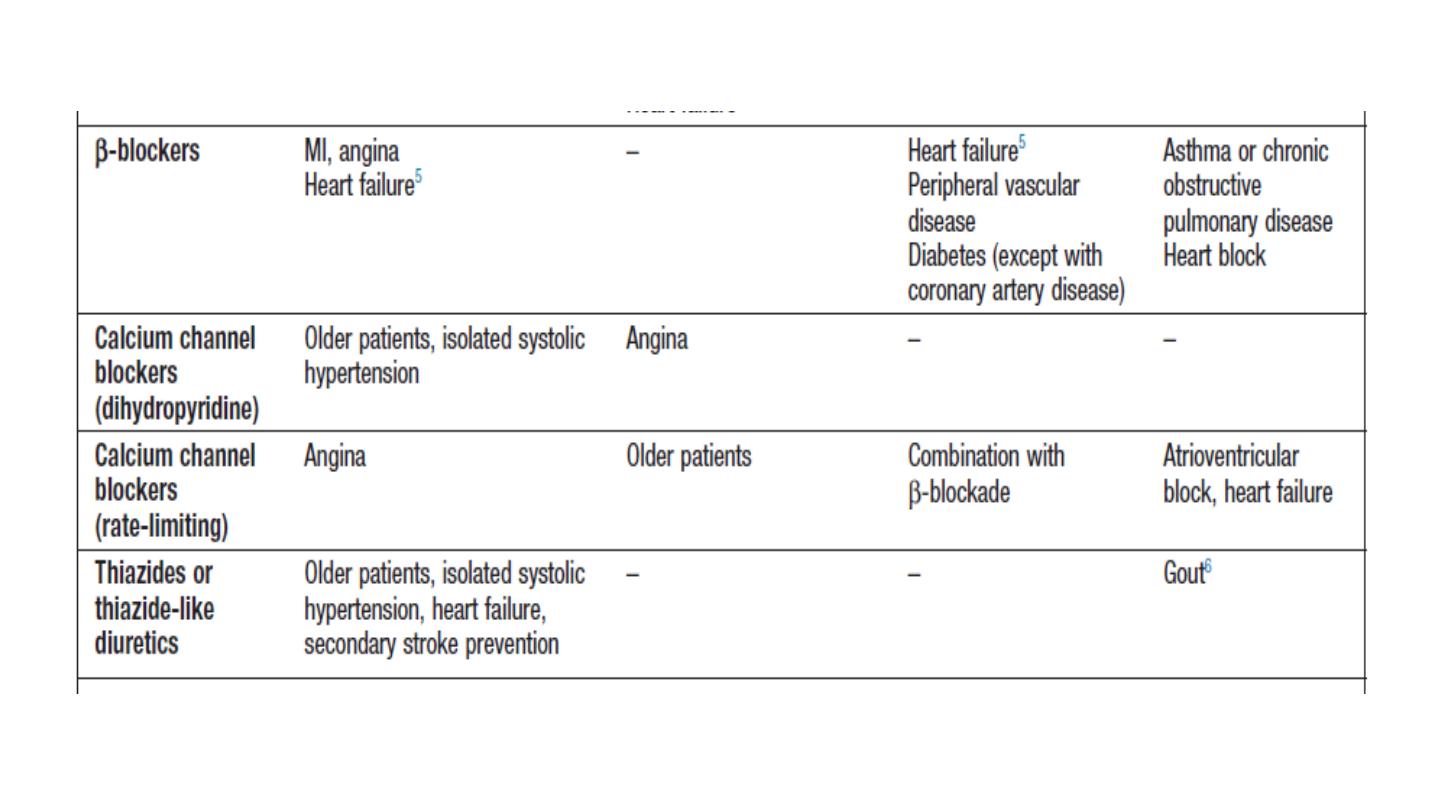

Beta-blockers.

These are no longer used as first-line antihypertensive therapy, except

in patients with another indication for the drug (e.g. angina).

Carvedilol and labetalol combined alpha and beta blocker

OTHER DRUGS

Alpha blockers: such as prazosin (0.5–20 mg daily in divided doses),

indoramin (25–100 mg twice daily) and doxazosin (1–16 mg daily

Alpha methyl dopa

Direct vasodilator: hydralazine (25–100 mg twice daily) and minoxidil

(10–50 mg daily).

Side-effects include first-dose and postural hypotension, headache,

tachycardia and fluid retention. Minoxidil also causes increased facial

hair and is therefore unsuitable for female patients.

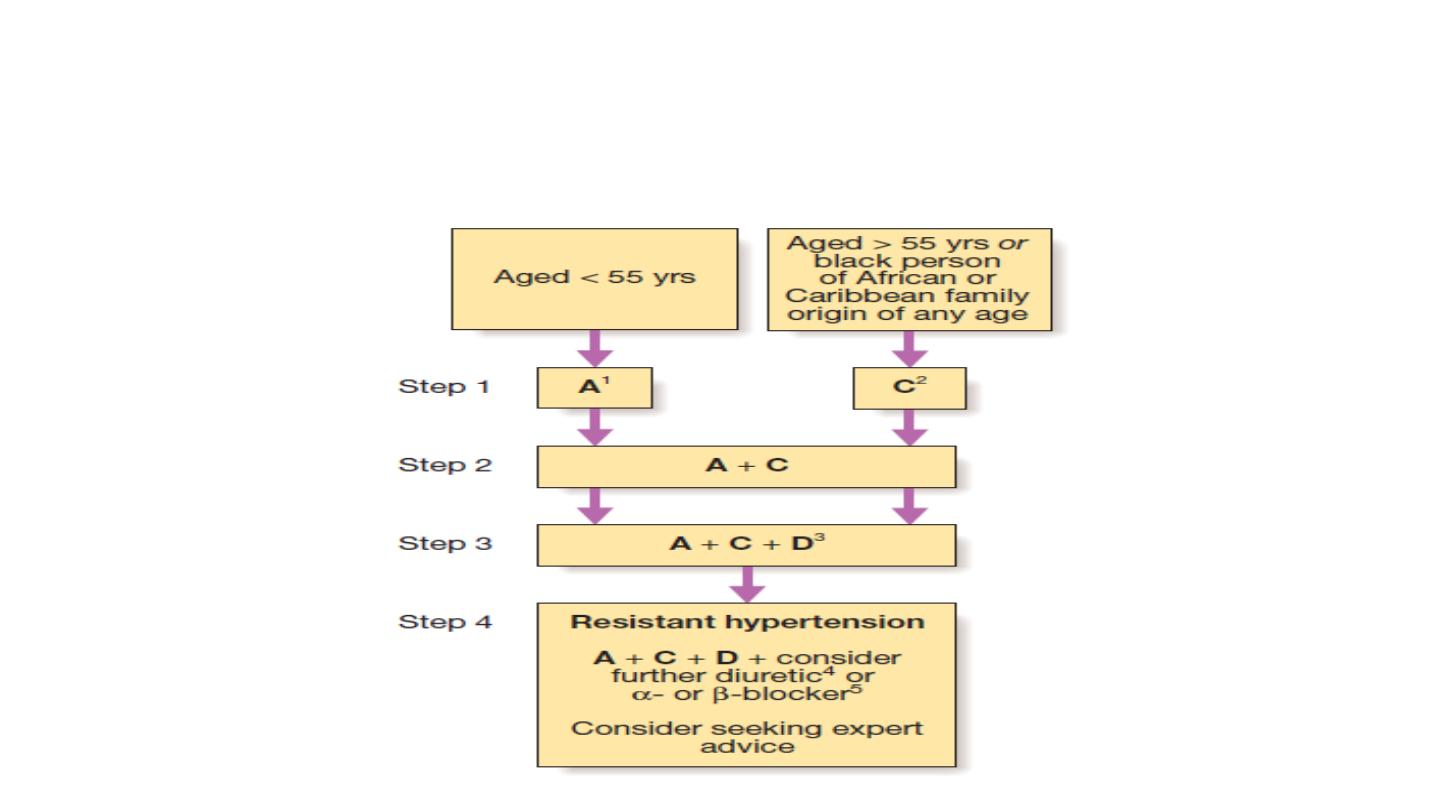

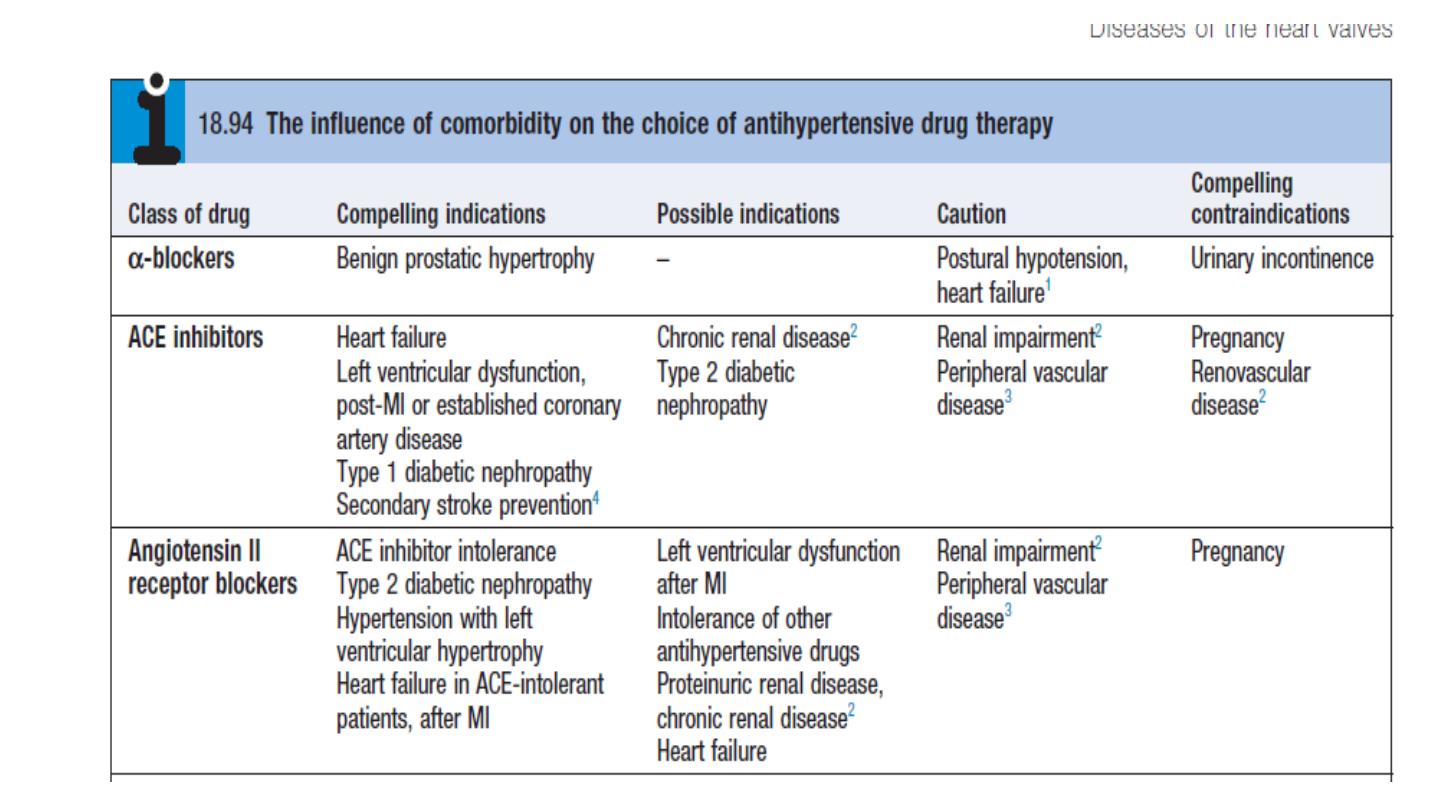

Choice of antihypertensive

:

Trials that have compared thiazides, calcium antagonists, ACE inhibitors

and angiotensin receptor blockers have not shown consistent differences

in outcome, efficacy, side-effects or quality of life. Beta-blockers, which

previously featured as first-line therapy in guidelines, have a weaker

evidence base.

The choice of antihypertensive therapy is initially dictated by the patient’s

age and ethnic background, although cost and convenience will affect the

exact drug and preparation used. Response to initial therapy and side-

effects dictate subsequent treatment. Comorbid conditions also have an

influence on initial drug selection for example, a β-blocker might be the

most appropriate treatment for a patient with angina. Thiazide diuretics

and dihydropyridine calcium channel antagonists are the most suitable

drugs for the treatment of high BP in older people

Choice of antihypertensives drugs according to

age

Combination versus monotherapy

Although some patients can be satisfactorily treated with a single

antihypertensive drug, a combination of drugs is often required to

achieve optimal BP control.

Combination therapy may be desirable for other reasons; for example,

low-dose therapy with two drugs may produce fewer unwanted effects

than treatment with the maximum dose of a single drug. Some drug

combinations have complementary or synergistic actions; for example,

thiazides increase activity of the renin–angiotensin system while ACE

inhibitors block it.

Emergency treatment of accelerated phase or malignant hypertension

In accelerated phase hypertension, lowering BP too quickly may compromise

tissue perfusion (due to altered autoregulation) and can cause cerebral

damage, including occipital blindness, and precipitate coronary or renal

insufficiency.

Even in the presence of cardiac failure or hypertensive encephalopathy, a

controlled reduction to a level of about 150/90 mmHg over a period of 24–48

hours is ideal.

In most patients, it is possible to avoid parenteral therapy and

bring BP under control with bed rest and oral drug therapy.

Intravenous or intramuscular labetalol (2 mg/min to a maximum

of 200 mg), intravenous glyceryl trinitrate (0.6–1.2 mg/hr),

intramuscular hydralazine (5 or 10 mg aliquots repeated at half

hourly intervals) and intravenous sodium nitroprusside (0.3–1.0

μg/kg body weight/min) are all effective but require careful

supervision, preferably in a high dependency unit.

Causes of refractory hypertension:

Poor compliance

Inadeqaute therapy

Secondory cause

Feature suggestive of secondary HPT:

AGE less than 30 , above 55 years, REFRACTORY HPT