Pathology of the small

and large intestine

Abdominal Hernia

Any weakness or defect in the wall of the

peritoneal cavity may permit protrusion of a

serosa-lined pouch of peritoneum called a

hernia sac.

Acquired hernias most commonly occur

anteriorly, through the inguinal and femoral

canals or umbilicus, or at sites of surgical scars.

These are of concern because of visceral

protrusion (

external herniation

).

Inguinal hernias

It tend to have narrow orifices and large sacs.

Small bowel loops are herniated most often, but

portions of omentum or large bowel also

protrude, and any of these may become

entrapped.

Pressure at the neck of the pouch may impair

venous drainage, leading to stasis and edema.

These changes increase the bulk of the herniated

loop, leading to permanent entrapment

and over

time, arterial and venous compromise, or

strangulation,

can result in infarction.

Vascular disorders of bowel

The greater portion of the gastrointestinal tract is

supplied by the celiac, superior mesenteric, and inferior

mesenteric arteries.

As they approach the intestinal wall, the superior and

inferior mesenteric arteries fan out to form the

mesenteric arcades.

Interconnections between arcades, as well as collateral

supplies from the proximal celiac and distal pudendal and

iliac circulations, make it possible for the small intestine

and colon to tolerate slowly progressive loss of the blood

supply from one artery.

By contrast, acute compromise of any major vessel can

lead to infarction of several meters of intestine.

Ischemic bowel disease

• Ischemic damage to the bowel wall can range from

mucosal infarction,

extending no deeper than the

muscularis mucosa;

to

mural infarction

of mucosa

and submucosa; to

transmural infarction

involving

all three layers of the wall.

• Mucosal or mural infarctions often are secondary

to acute

or chronic

hypoperfusion,

transmural

infarction is generally

caused by acute vascular

obstruction.

Causes of

acute arterial obstruction

• Severe

atherosclerosis

(which is often prominent at

the origin of mesenteric

vessels),

aortic aneurysm.

•

Hypercoagulable states, oral contraceptive use.

•

Embolization of cardiac vegetations or aortic

atheromas.

Causes of intestinal hypoperfusion

•

Cardiac failure.

•

Shock.

•

Dehydration.

•

Vasoconstrictive drugs.

Damage intestinal arteries

Systemic

vasculitides,

such as polyarteritis nodosum,

Henoch-Shonlein purpura, or Wegener granulomatosis.

PATHOGENESIS

Intestinal responses to ischemia occur in two phases.

The initial hypoxic injury occurs at the onset of vascular

compromise and, although some damage occurs,

intestinal epithelial cells are relatively resistant to

transient hypoxia.

, is initiated by

reperfusion injury

The second phase,

restoration of the blood supply and associated with the

greatest damage. In severe cases multiorgan failure may

occur. While the underlying mechanisms of reperfusion

injury are incompletely understood, they involve free

radical production, neutrophil infiltration, and release of

inflammatory mediators, such as complement proteins

and cytokines.

• The severity of vascular compromise, time frame

during which it develops, and vessels affected are

the major variables that determine severity of

ischemic bowel disease.

Tumors of the small and large intestine:

Non neoplastic polyp:

Adenoma:

Familial polyposis syndrome:

Colorectal carcinoma:

Gastrointestinal lymphoma:

GIST:

• Polyps

• Polyps are most common in the colon but may occur

in the esophagus, stomach, or small intestine.

•

sessile

, grow directly from the stem without a stalk.

•

pedunculated

Polyps with stalks.

• Intestinal polyps can be classified as non-neoplastic or

neoplastic in nature.

• The most common neoplastic polyp is the adenoma,

which has the potential to progress to cancer.

• The non-neoplastic polyps can be classified as

inflammatory, hamartomatous, or hyperplastic.

Non neoplastic Polyps

Hyperplastic

• Asymptomatic.

• Less than 5 mm.

• Single or multiple.

• Rectosigmoid.

• No malignant

potential.

Hamartomatous

• Peutz-Jegher (AD)

• Multiple, whole of GIT

• Mucocutaneous pigment.

• Risk of GI and non-GI Ca.

• Juvenile:

• children < 5Y, quite large.

• Rectum.

• No malignant potential.

Inflammatory polyps

Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome

.

Patients present with a clinical triad of rectal bleeding, mucus

discharge, and an inflammatory lesion of the anterior rectal

wall.

The underlying cause is impaired relaxation of the anorectal

sphincter that creates a sharp angle at the anterior rectal shelf

and leads to recurrent abrasion and ulceration of the

overlying rectal mucosa. An inflammatory polyp may

ultimately form as a result of chronic cycles of injury and

healing.

Entrapment of this polyp in the fecal stream leads to mucosal

prolapse.

Histologic features:

Inflammatory polyp with superimposed mucosal prolapse

and include lamina propria fibromuscular hyperplasia, mixed

inflammatory infiltrates, erosion, and epithelial hyperplasia.

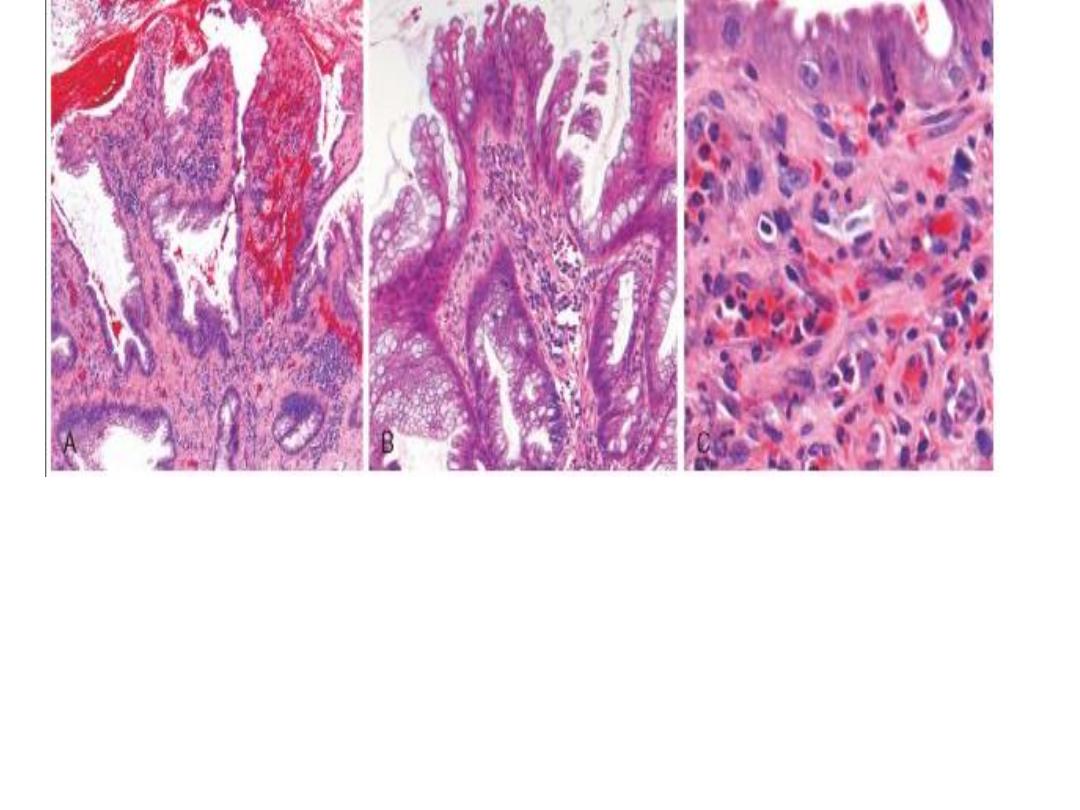

Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome.

A, The dilated glands, proliferative epithelium, superficial erosions, and

inflammatory infiltrate are typical of an inflamatory polyp.The smooth muscle

hyperplasia within the lamina propria suggests that mucosal prolapse has also

occurred.

B, Epithelial hyperplasia.

C, Granulation tissue-like capillary proliferation within the lamina propria caused

by repeated erosion and re-epithelialization

• Hamartomatous polyps

• It’s occur sporadically and in the context of various

genetically determined or acquired syndromes.

• Hamartomas are tumor-like growths composed of

mature tissues that are normally present at the site

in which they develop.

• Hamartomatous polyposis syndromes are rare,

they are important to recognize because of

associated intestinal and extra-intestinal

manifestations and the possibility that other family

members are affected.

Hyperplastic polyps

Common epithelial proliferations.

Discovered in the sixth and seventh decades of life.

Pathogenesis of hyperplastic polyps is incompletely

decreased

they are thought to result from

understood, but

epithelial cell turnover and delayed shedding of surface

epithelial cells, leading to a “piling up” of goblet cells and

absorptive cells.

These lesions are without malignant potential.

they must be distinguished from sessile serrated adenomas,

histologically similar lesions that have malignant potential

.

It is also important to remember that epithelial hyperplasia

can occur as a nonspecific reaction adjacent to or overlying

any mass or inflammatory lesion and, therefore, can be a clue

to the presence of an adjacent, clinically important lesion.

Morphology

Gross:

Hyperplastic polyps are most commonly found in the left

colon and are typically less than 5 mm in diameter.

They are smooth, nodular protrusions of the mucosa,

often on the crests of mucosal folds.

Single or multiple, particularly in the sigmoid colon and

rectum.

Microscopically:

Hyperplastic polyps are composed of mature goblet and

absorptive cells.

The delayed shedding of these cells leads to crowding

architecture that is the

serrated surface

that creates the

morphologic hallmark of these lesions.

Adenomatous Polyps

epithelial proliferation and dysplasia

Four types: tubular, villous, mixed, and sessile

serrated adenoma.

Risk of malignancy related to size, histologic type, and

dysplasia

Since they are considered premalignant, all should be

removed.

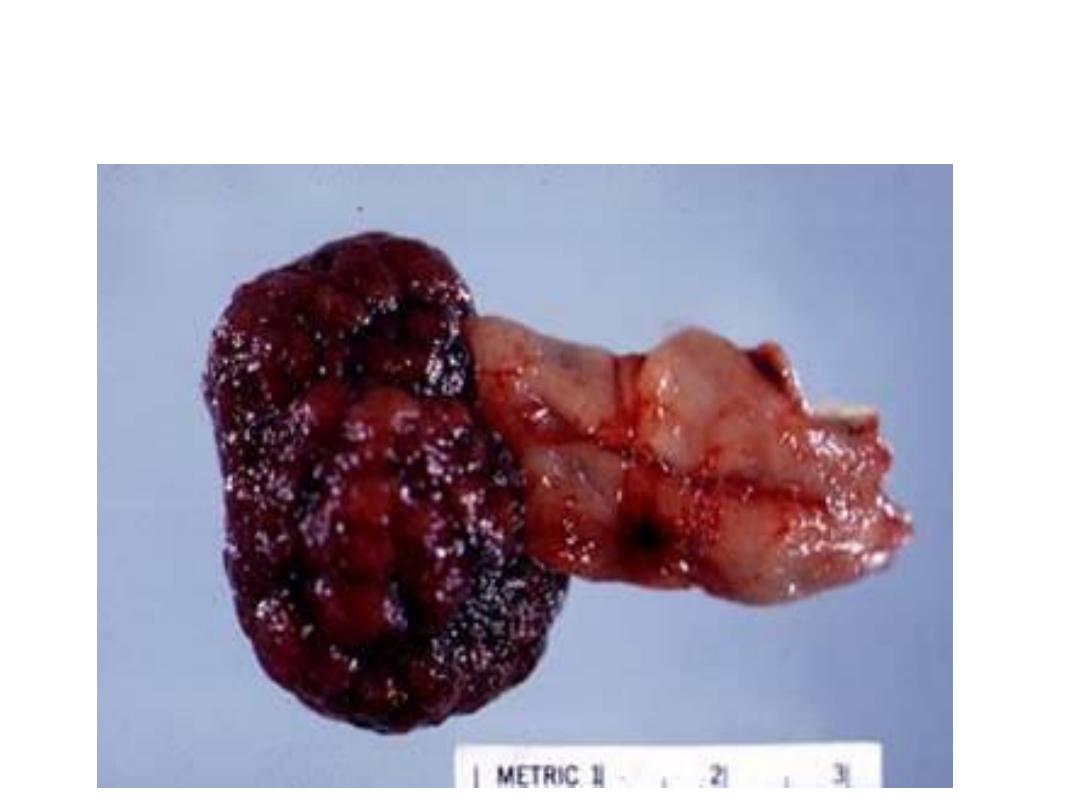

Large pedunculated adenomatous colonic polyp

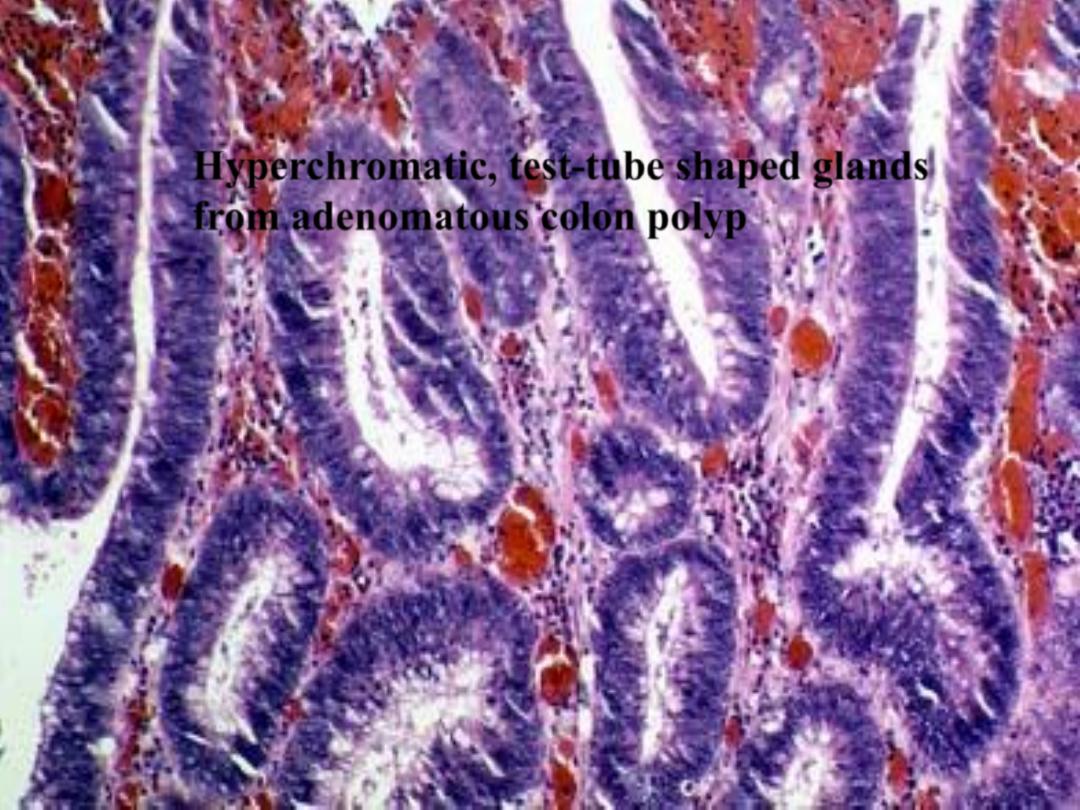

Hyperchromatic, test-tube shaped glands

from adenomatous colon polyp

Colorectal adenocarcinoma

• Majority of ca. in large bowel 98%.

• Both genetic, hereditary & environmental

causes.

• Increasing age &inflammatory bowel

disease.

• Dietary causes.

• Adenoma predispose to ca colon.

NSAID have protective effects.

Colon Adenocarcinoma

• Right colon:

– increasing incidence, especially in elderly

– usually polypoid

– present with bleeding, anemia

• Left colon:

– annular, napkin ring lesions

– present with decreased stool caliber, obstruction

Less than half of cancers are detectable by

proctoscopic exam

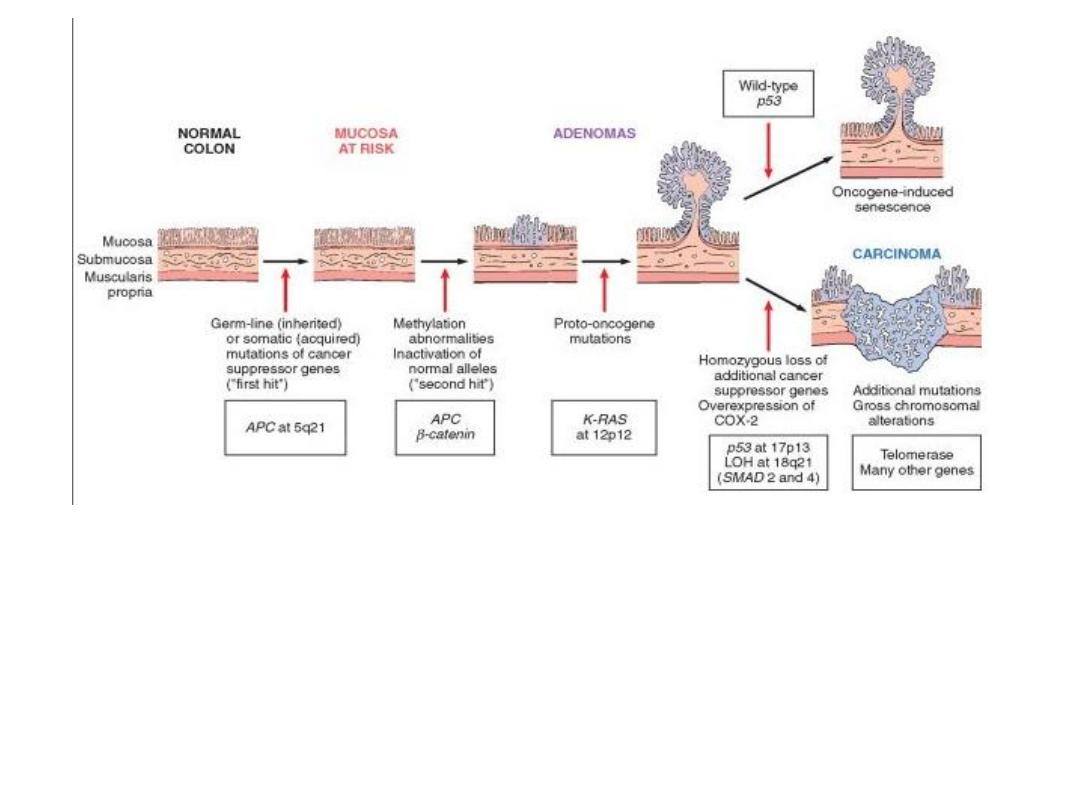

Molecular model for the evolution of colorectal cancers through the

adenoma-carcinoma sequence.

Although

APC

mutation is an early event and loss of

p53

occurs late in the

process of tumorigenesis, the timing for the other changes may be variable.

Note: individual tumors may not have all of the changes listed.

Top right

, cells that gain oncogene signaling without loss of p53 eventually

enter oncogene-induced senescence

Function

Type

Locus

Gene

Regulate intracellular

b-catenin levels Proliferation/

apoptosis/cell

adhesion

Gate keeper

Tumor

suppressor

5q

APC

Membrane associated

G protein

Growth factor signal

transduction

Oncogene

12P

K RAS

TGF-b signaling

pathway

Growth inhibition

signal transduction

Tumor

suppressor

18q

SMAD 2,4

Cell interactions/

adhesion

Apoptosis

Tumor

suppressor

18q

DCC

Cell cycle checkpoint

Apoptosis

Tumor

suppressor

17p

P53

Morphology of colonic adenocarcinoma:

Gross:

Site: 25% in the cecum &ascending colon, 25% in

the descending colon and proximal sigmoid,

the remaining scattered elsewhere.

1. Polypoid growth in the proximal.

2. Annual encirculing lesion in distal colon.

Microscopically:

Hereditary Colon Cancer Sy.

• Familial Adenomatous Polyposis

– autosomal dominant

– mutation in APC gene on 5q21

– 100-2500 polyps throughout GI tract

– virtually 100% risk of carcinoma

• HNPCC (Lynch Syndrome)

– autosomal dominant

– increased risk of GI and non-GI cancers

– lower numbers of polyps than FAP

Hereditary Syndromes Involving the Gastrointestinal Tract

Pathology in GI Tract

Altered Gene

Syndromes

Multiple adenomatous

polyps

APC

Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP)

• Classic FAP

• Attenuated FAP

• Gardner syndrome

• Turcot syndrome

Hamartomatous polyps

STK11

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome

Juvenile polyps

SMAD4

Juvenile polyposis syndrome

BMPRIA

Colon cancer

Defects in mismatch DNA repair

genes

Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal

carcinoma

Inflammatory polyps

TSC1

Tuberous sclerosis

TSC2

Hamartomatous polyps

PTEN

Cowden disease

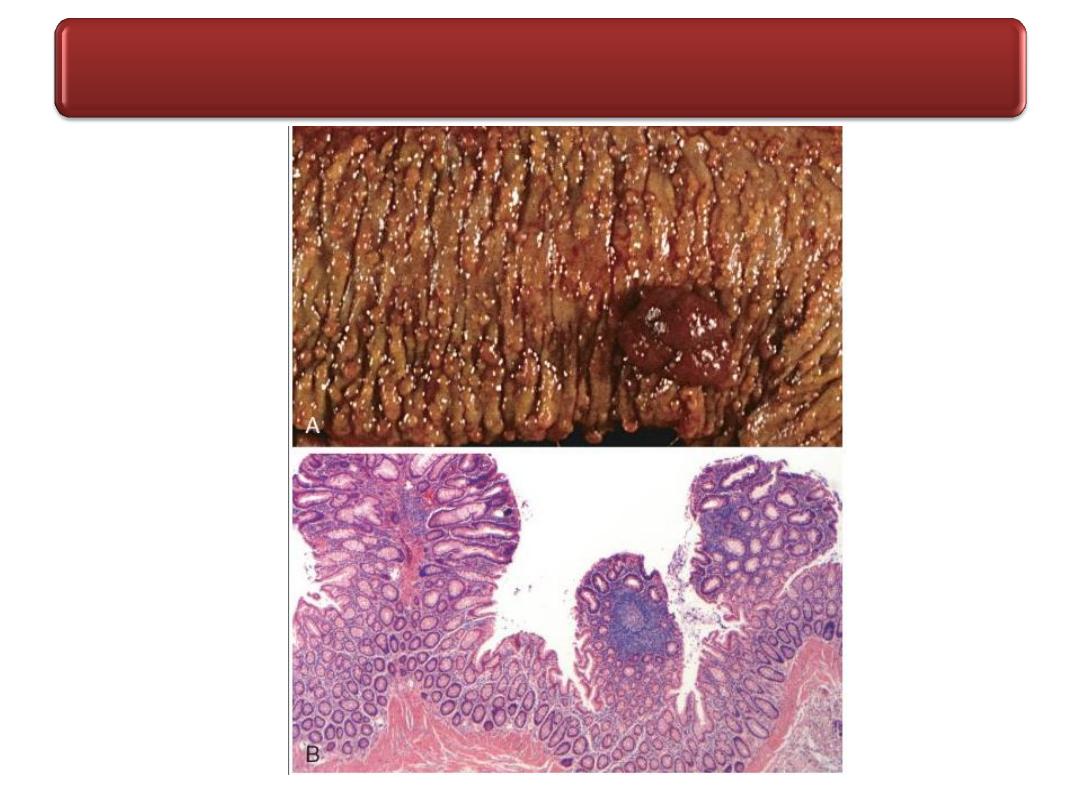

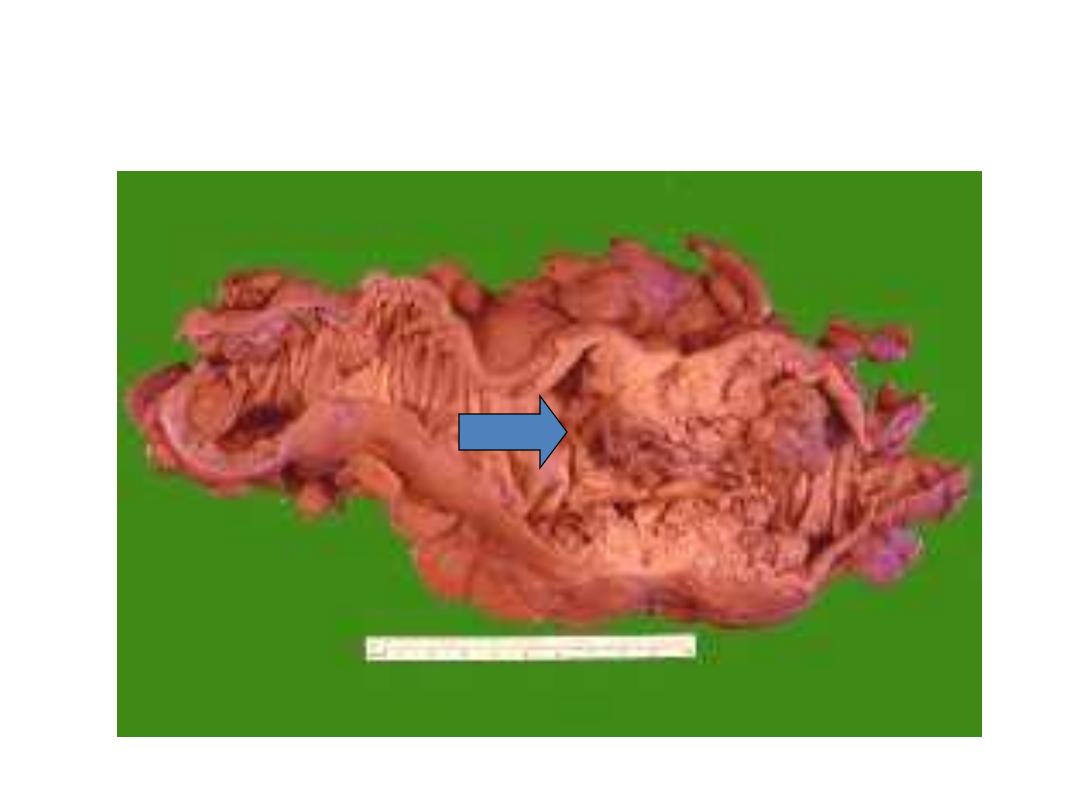

Familial Adenomatous Polyposis

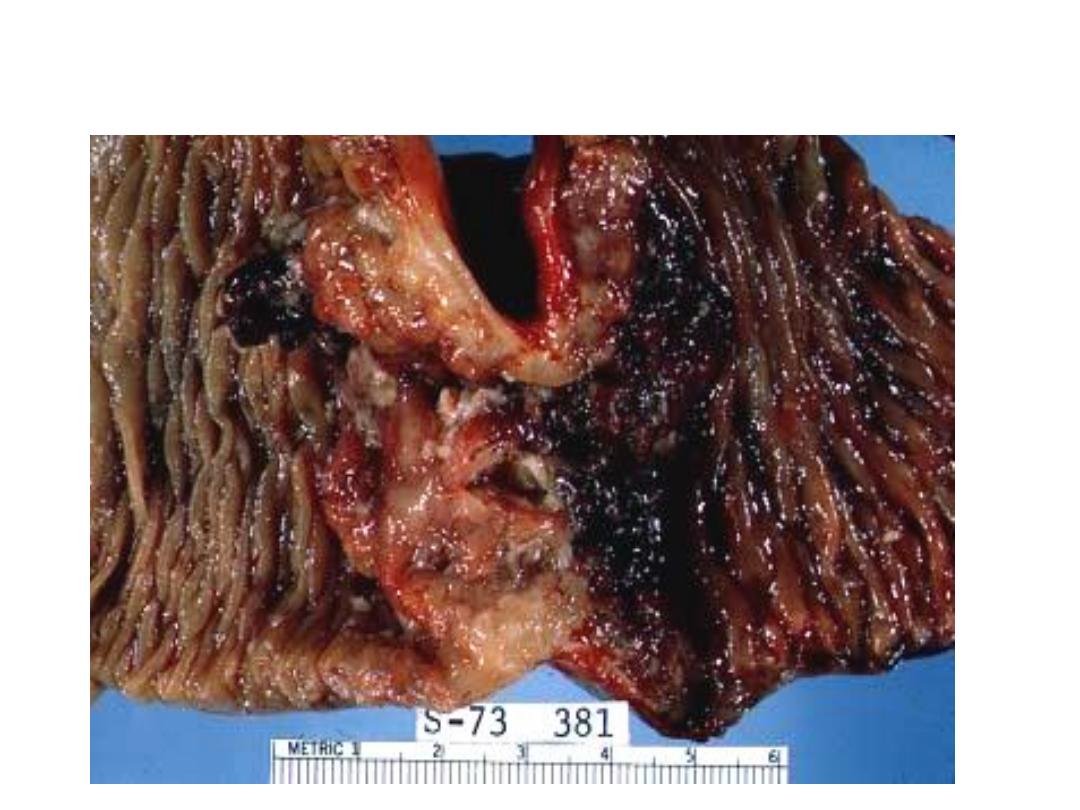

Constricting “napkin ring” Ca

Large Fungating Ca Colon:

Carcinoma Colon

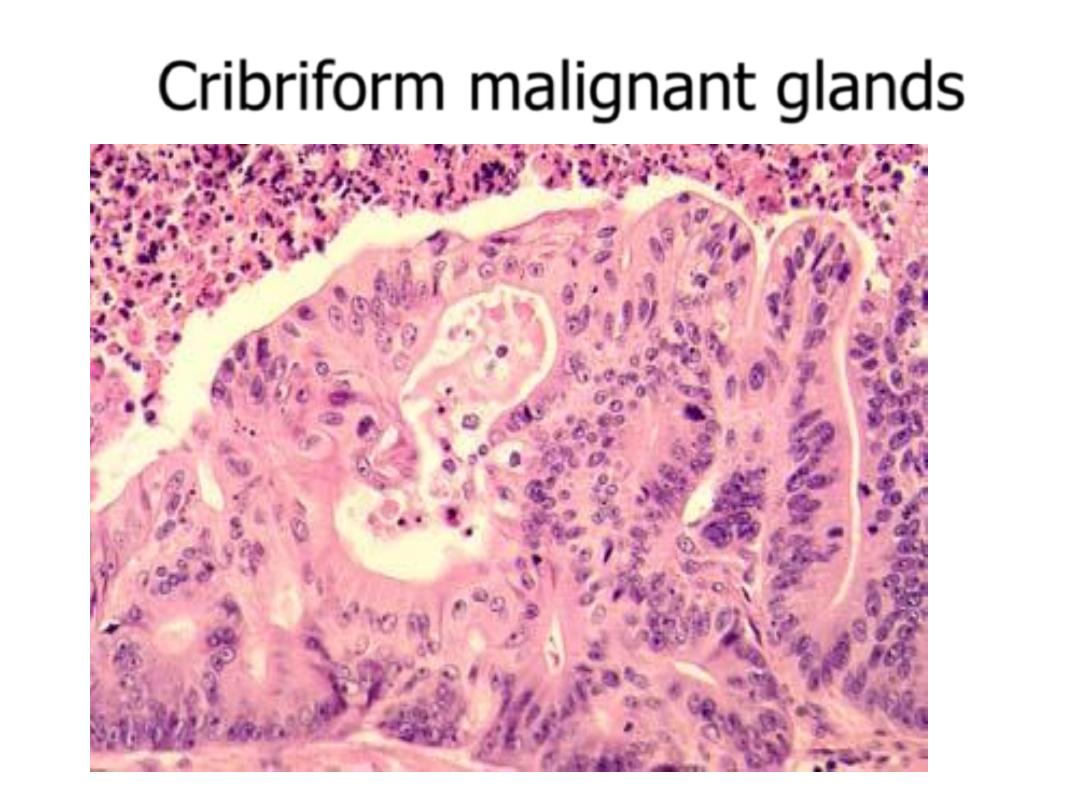

Cribriform malignant glands

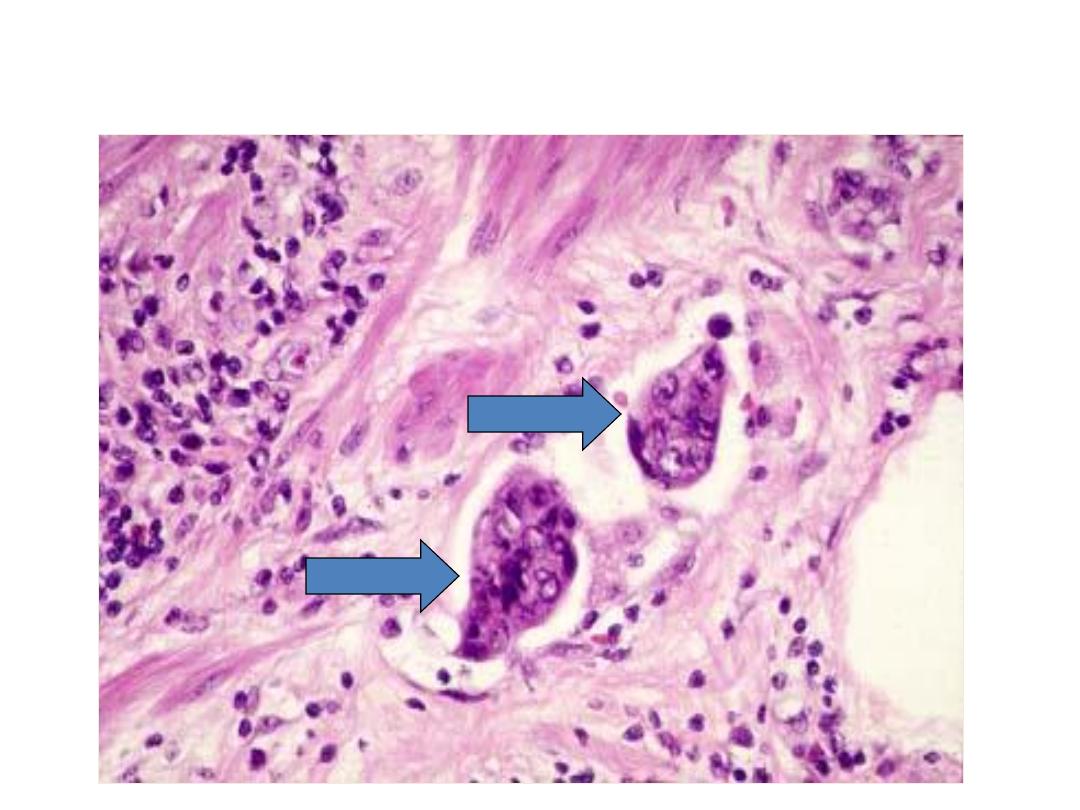

Lymphatic invasion

Tumors of the Anal Canal

The anal canal can be divided into thirds. The upper zone is

lined by columnar rectal epithelium; the middle third by

transitional epithelium; and the lower third by stratified

squamous epithelium. Carcinomas of the anal canal may have

typical glandular or squamous patterns of differentiation,

recapitulating the normal epithelium of the upper and lower

thirds, respectively. An additional differentiation pattern,

termed

basaloid

, is present in tumors populated by immature

cells derived from the basal layer of transitional epithelium.

When the entire tumor displays a basaloid pattern, the archaic

term

cloacogenic carcinoma

is still often applied.

Basaloid differentiation may be mixed with squamous or

mucinous differentiation. All are considered variants of anal

canal carcinoma. Pure squamous cell carcinoma of the anal

canal is frequently associated with HPV infection, which also

causes precursor lesions such as

condyloma accuminatum.

Carcinoid Tumors-pathology

• Solitary or multicentric firm, yellow-tan nodules

• Usually submucosal masses, sometimes with

ulceration

• Cause striking desmoplastic response

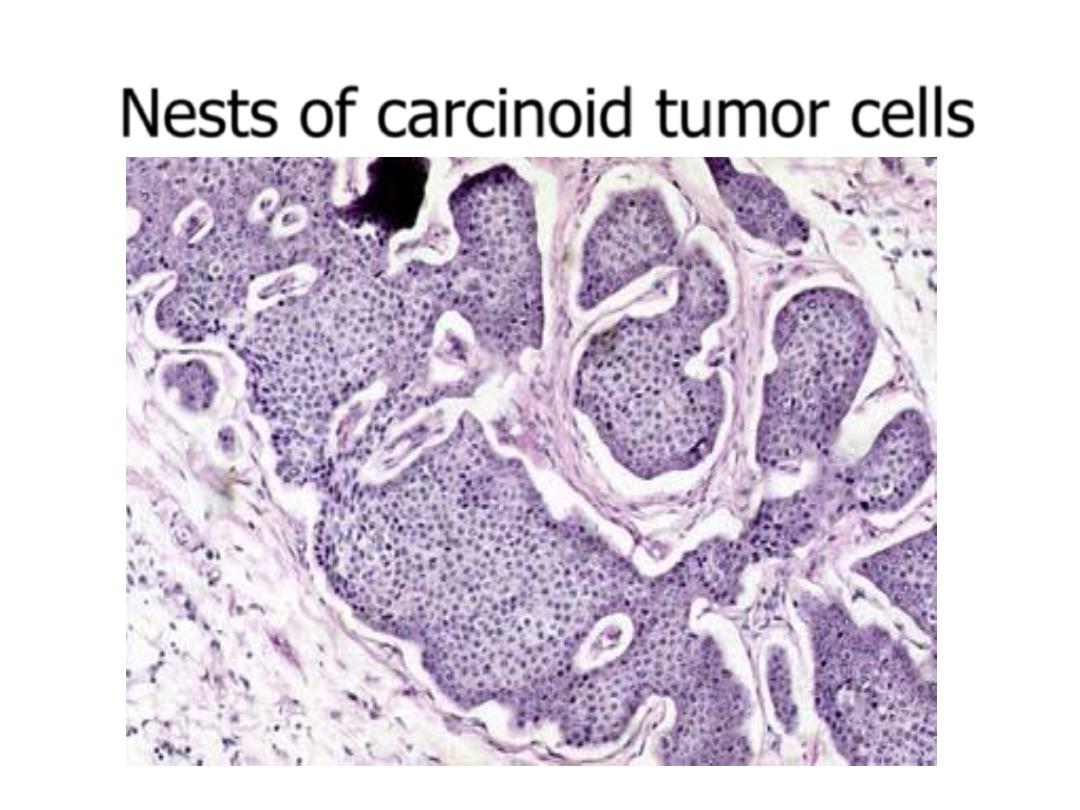

• Form islands, trabeculae, glands, or sheets

• Monotonous, speckled nuclei and abundant pink

cytoplasm

• Contain cytoplasmic secretory dense-core granules

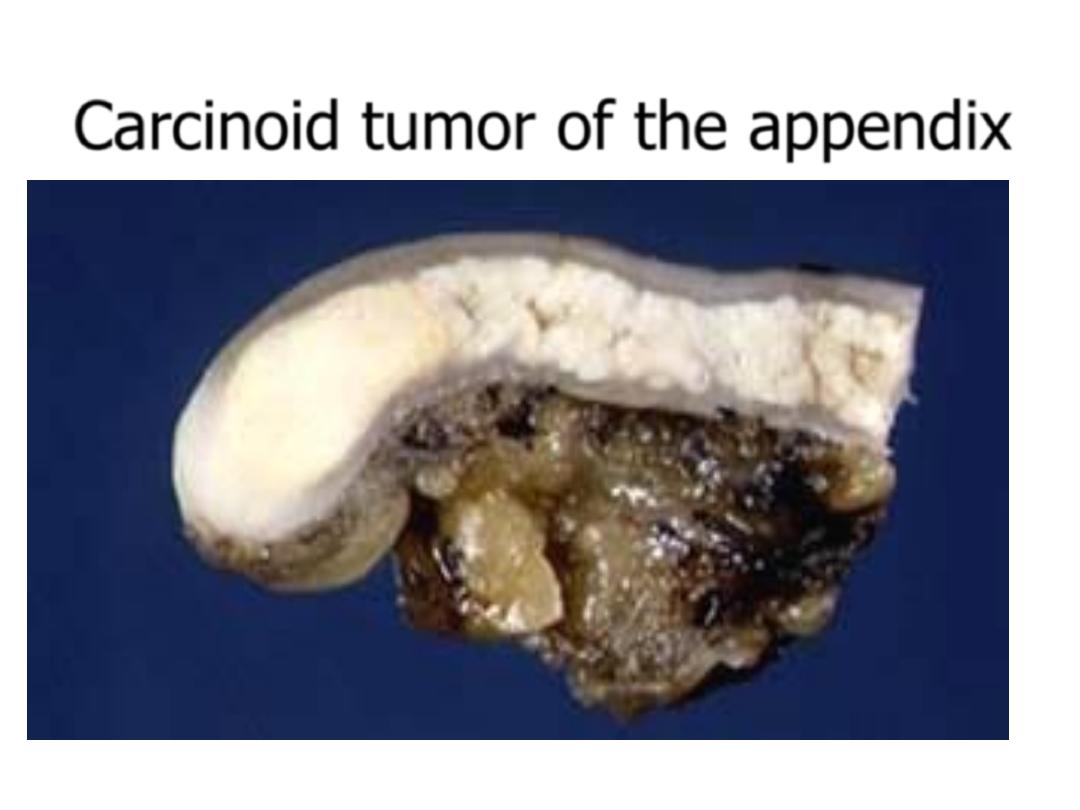

Carcinoid tumor of the appendix

Nests of carcinoid tumor cells

Gastrointestinal Lymphoma

• Most common primary extranodal lymphoma

location

• Sporadic/Western type-most common.

• Thought to arise from Mucosal Associated

Lymphoid Tissues

• Controversial relationship with H. pylori

• T-cell lymphomas associated with celiac sprue

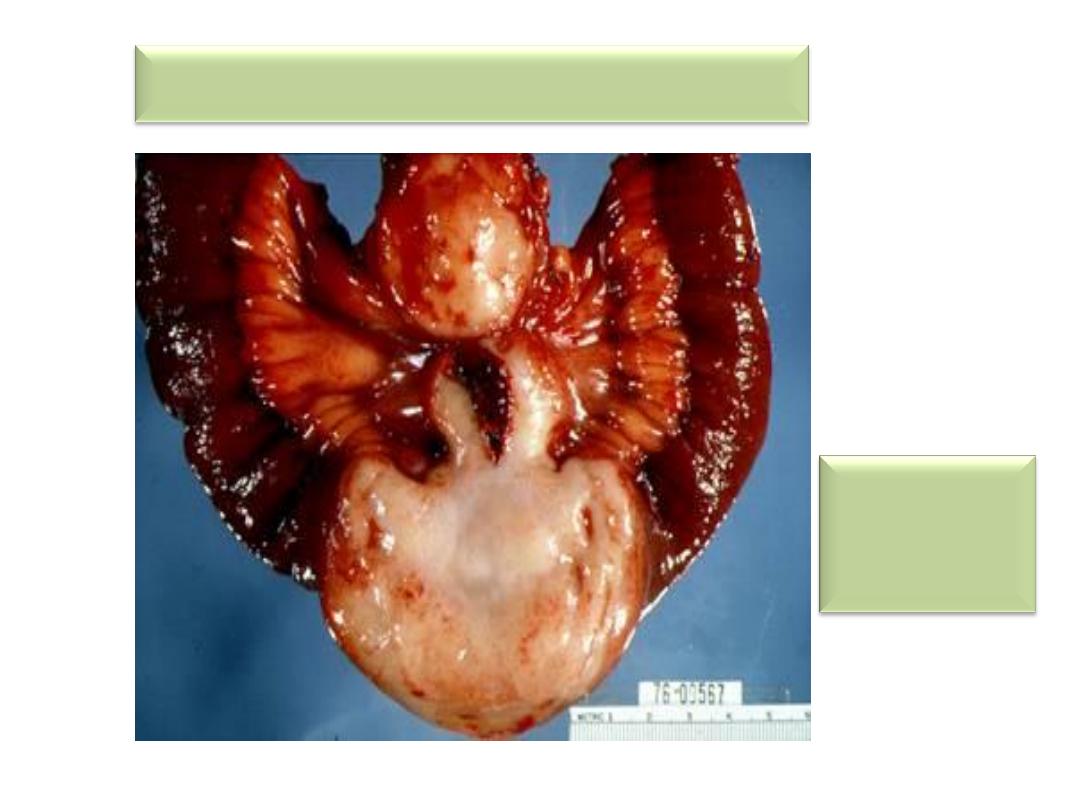

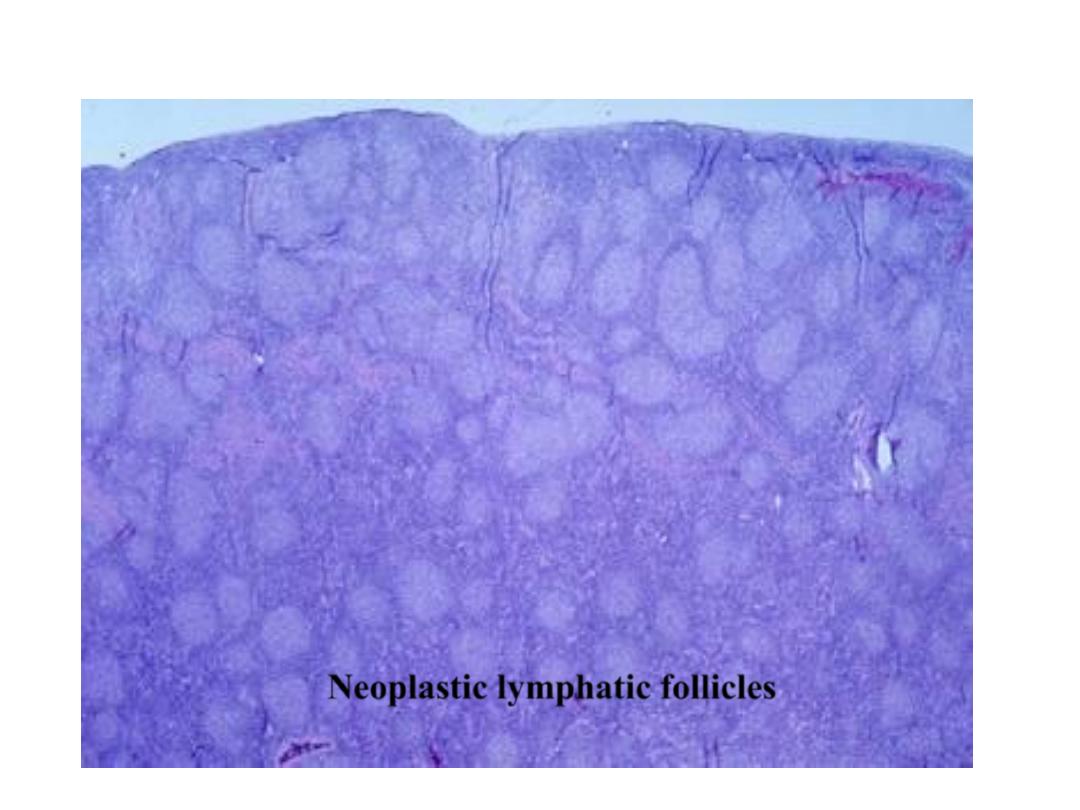

Intestinal B-cell lymphoma

Fleshy

Lymphatic

tumor

Neoplastic lymphatic follicles

• GIST

• Approximately 75% to 80% of all GISTs have oncogenic,

gain-of-function mutations of the gene encoding the

tyrosine kinase c-KIT, which is the receptor for stem cell

factor. Another 8% of GISTs have mutations that activate a

related tyrosine kinase, platelet-derived growth factor

receptor A (PDGFRA); thus activating mutations in

tyrosine kinases are found in virtually all GISTs. However,

either mutation is sufficient for tumorigenesis, and c-KIT

and PDGFRA mutations are almost never found in a single

tumor.

• GISTs appear to arise from, or share a common stem cell

with, the interstitial cells of Cajal, which express c-KIT, are

located in the muscularis propria, and serve as

pacemaker cells for gut peristalsis.

• MORPHOLOGY

• Primary gastric GISTs usually form a solitary, well

circumscribed,

• fleshy, submucosal mass. Metastases may form

multiple small serosal nodules or fewer large

nodules in the liver; spread outside of the

abdomen is uncommon.

• GISTs can be composed of thin, elongated spindle

cells or plumper epithelioid cells. The most

useful diagnostic marker is c-KIT, consistent with

the relationship between GISTs and interstitial

cells of Cajal, which is immunohistochemically

detectable in 95% of these tumors.

Clinical Features

• Symptoms of GISTs at presentation may be

related to mass effects or mucosal ulceration.

Complete surgical resection is the primary

treatment for localized gastric GIST.

• The prognosis correlates with tumor size, mitotic

index, and location, with gastric GISTs being

somewhat less aggressive than those arising in

the small intestine. Recurrence or metastasis is

rare for gastric GISTs less than 5 cm across but

common for mitotically active tumors larger than

10 cm.