1

Babylon University Stage Fourth

College of Medicine Lecture 1

Dr. Athraa Falah

THE HEPATIC PATHOLOGY

General Features of Hepatic Disease

The major primary diseases of the liver are viral hepatitis, alcoholic liver disease, nonalcoholic

fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

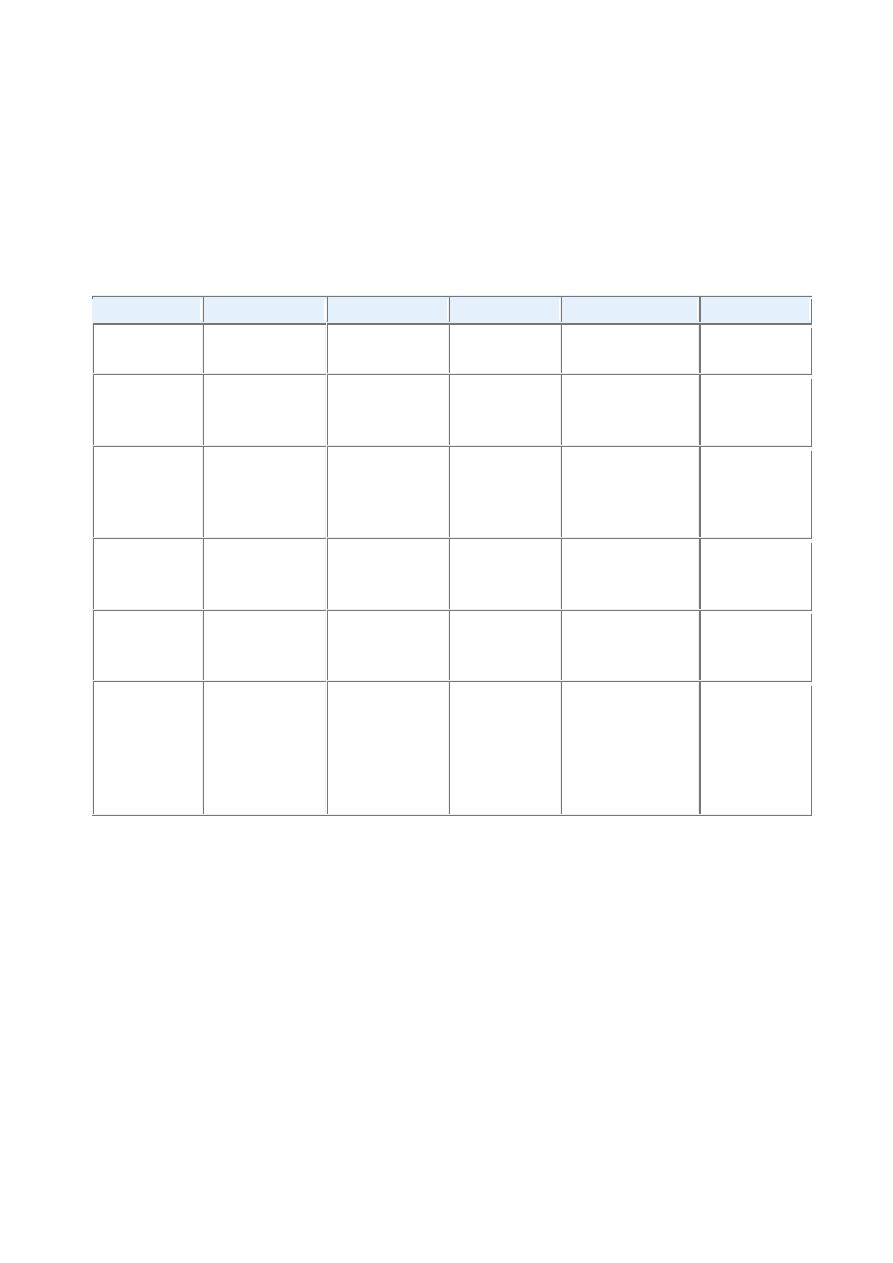

In the table below there are the most important laboratory tests that evaluate the liver function.

Table -- Laboratory Evaluation of Liver Disease

Hepatocyte integrity

Serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST)

Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT)

Biliary function

Serum bilirubin (total and direct)

Serum alkaline phosphatase

Hepatocyte function

Serum albumin

Prothrombin time

Patterns of hepatic injury

• Hepatocyte degeneration and intracellular accumulations

• Hepatocyte necrosis and apoptosis

• Inflammation

• Regeneration

• Fibrosis

Clinical Syndromes related to liver disease

1. Jaundice and Cholestasis.

2. Hepatic Failure

3. Cirrhosis

4. Portal Hypertension

2

Jaundice and cholestasis

Alterations of bile formation become clinically evident as yellow discoloration of the skin and

sclera (jaundice and icterus, respectively) due to retention of bilirubin, and as cholestasis,

characterized by systemic retention of not only bilirubin but also other solutes eliminated in bile.

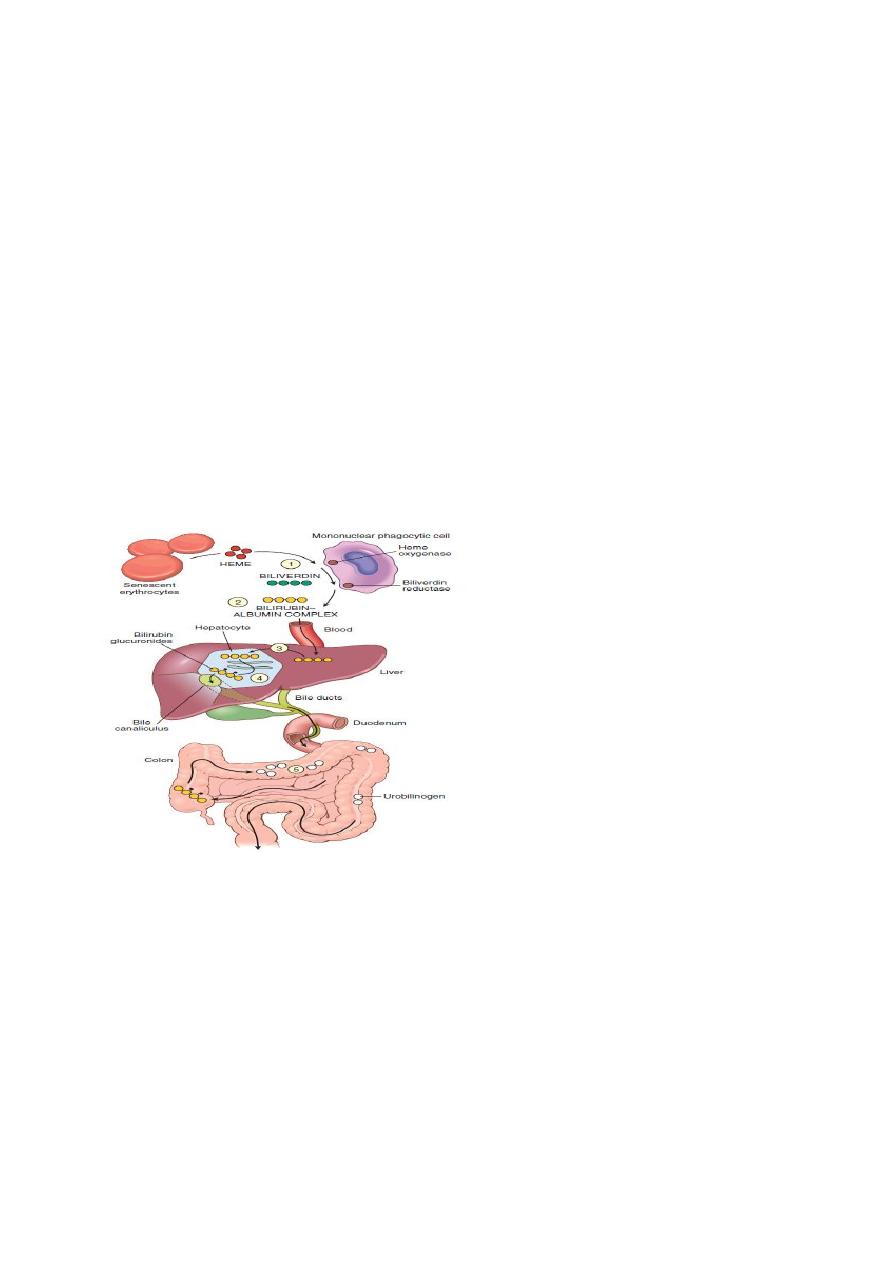

Bilirubin metabolism and elimination.

(1) Normal bilirubin production from heme (0.2–0.3 gm/day) is derived primarily from the

breakdown of senescent circulating erythrocytes.

(2) Extrahepatic bilirubin is bound to serum albumin and delivered to the liver.

(3) Hepatocellular uptake and (4) glucuronidation in the endoplasmic reticulum generate bilirubin

monoglucuronides and diglucuronides, which are water soluble and readily excreted into bile.

(5) Gut bacteria deconjugate the bilirubin and degrade it to colorless urobilinogens. The

urobilinogens and the residue of intact pigments are excreted in the feces, with some reabsorption

and excretion into urine.

Pathophysiology of Jaundice

There are two important pathophysiologic differences between the two forms of bilirubin.

Unconjugated bilirubin is virtually insoluble in water at physiologic pH and exists in tight

complexes with serum albumin. This form cannot be excreted in the urine even when blood levels

are high.

Normally, a very small amount of unconjugated bilirubin is present as an albumin-free anion in

plasma. This fraction of unbound bilirubin may diffuse into tissues, particularly the brain in

infants, and produce toxic injury which may cause severe neurologic damage, referred to as

kernicterus.

3

In contrast, conjugated bilirubin is water-soluble, nontoxic, and only loosely bound to albumin,

and can be excreted in urine.

Serum bilirubin levels in the normal adult vary between 0.3 and 1.2 mg/dL, Jaundice becomes

evident when the serum bilirubin levels rise above 2.0 to 2.5 mg/dL;

Jaundice occurs when the equilibrium between bilirubin production and clearance is disturbed by

one or more of the following mechanisms ( Table below ):

(1) excessive extrahepatic production of bilirubin;

(2) reduced hepatocyte uptake;

(3) impaired conjugation;

(4) decreased hepatocellular excretion; and

(5) impaired bile flow.

The first three mechanisms produce unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia, and the latter two produce

predominantly conjugated hyperbilirubinemia.

TABLE -- Causes of Jaundice

PREDOMINANTLY UNCONJUGATED HYPERBILIRUBINEMIA

Excess production of bilirubin

Hemolytic anemias

Resorption of blood from internal hemorrhage (e.g., alimentary tract bleeding,

hematomas)

Ineffective erythropoiesis (e.g., pernicious anemia, thalassemia)

Reduced hepatic uptake

Drug interference with membrane carrier systems

Some cases of Gilbert syndrome

Impaired bilirubin conjugation

Physiologic jaundice of the newborn {decreased UGT1A1(uridine diphosphate–

glucuronyltransferase1A1) activity, decreased excretion}

Breast milk jaundice (β-glucuronidases in milk)

Genetic deficiency of UGT1A1 activity (Crigler-Najjar syndrome types I and II)

Gilbert syndrome

Diffuse hepatocellular disease (e.g., viral or drug-induced hepatitis, cirrhosis)

PREDOMINANTLY CONJUGATED HYPERBILIRUBINEMIA

Deficiency of canalicular membrane transporters (Dubin-Johnson syndrome, Rotor syndrome)

Impaired bile flow

4

Neonatal Jaundice.

Because the hepatic machinery for conjugating and excreting bilirubin does not fully mature until

about 2 weeks of age, almost every newborn develops transient and mild unconjugated

hyperbilirubinemia, termed neonatal jaundice or physiologic jaundice of the newborn. This may be

exacerbated by breastfeeding, as a result of the presence of bilirubin-deconjugating enzymes in

breast milk

Hereditary Hyperbilirubinemias.

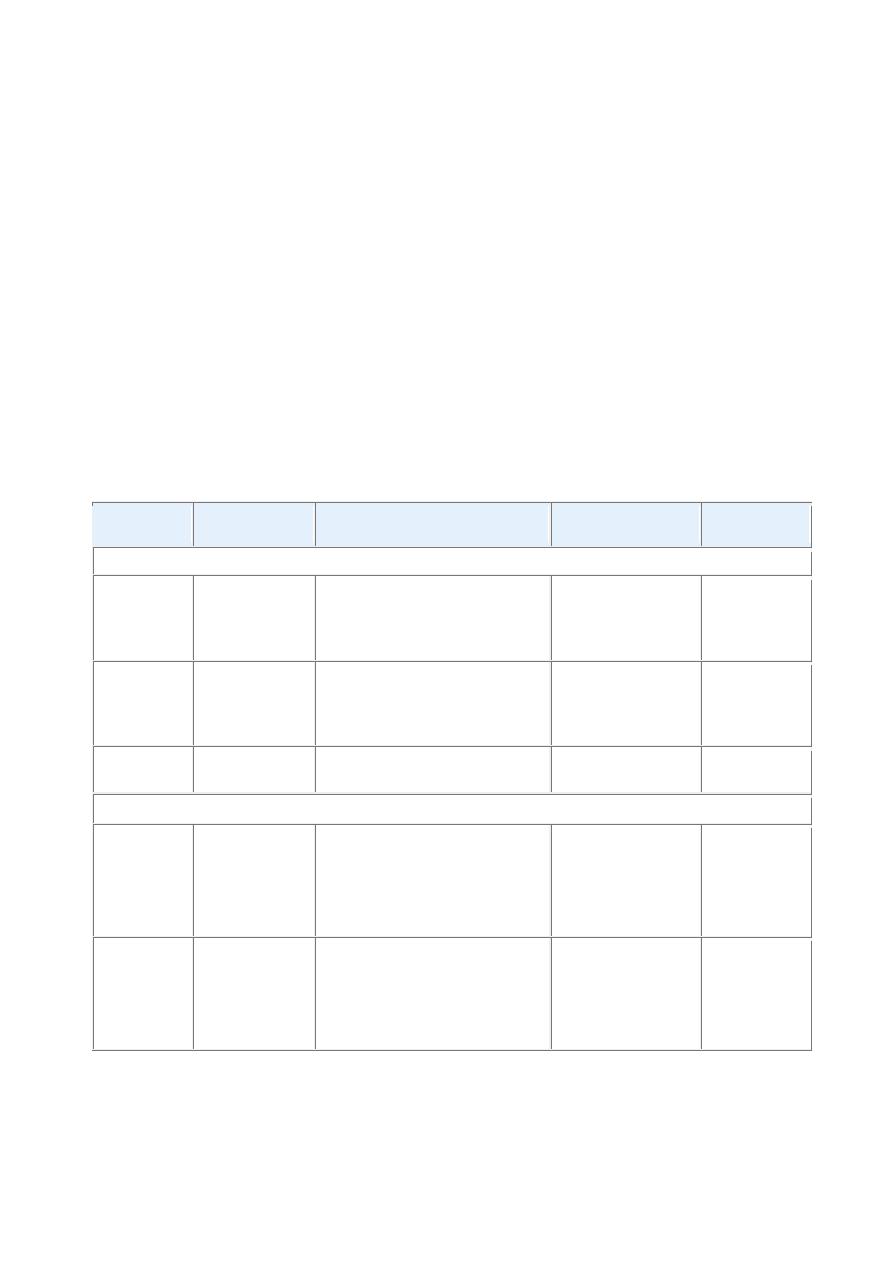

Multiple genetic mutations can cause hereditary hyperbilirubinemia(Tablebelow).

In Crigler-Najjar syndrome type I hepatic UGT1A1 is completely absent. The liver is

morphologically normal by light and electron microscopy. However, serum unconjugated

bilirubin reaches very high levels, producing severe jaundice and icterus. Without liver

transplantation, this condition is invariably fatal.

TABLE 18-3 -- Hereditary Hyperbilirubinemias

Disorder

Inheritance

Defects in Bilirubin Metabolism Liver Pathology

Clinical

Course

UNCONJUGATED HYPERBILIRUBINEMIA

Crigler-

Najjar

syndrome

type I

Autosomal

recessive

Absent UGT1A1 activity

None

Fatal

in

neonatal

period

Crigler-

Najjar

syndrome

type II

Autosomal

dominant

with

variable

penetrance

Decreased UGT1A1 activity

None

Generally

mild,

occasional

kernicterus

Gilbert

syndrome

Autosomal

recessive

Decreased UGT1A1 activity

None

Innocuous

CONJUGATED HYPERBILIRUBINEMIA

Dubin-

Johnson

syndrome

Autosomal

recessive

Impaired biliary excretion of

bilirubin glucuronides due to

mutation

in

canalicular

multidrug resistance protein 2

(MRP2)

Pigmented

cytopasmic

globules;

?epinephrine

metabolites

Innocuous

Rotor

syndrome

Autosomal

recessive

Decreased hepatic uptake

and storage?

Decreased

biliary

excretion?

None

Innocuous

5

Crigler-Najjar syndrome type II is a less severe, nonfatal disorder in which UGT1A1 enzyme

activity is greatly reduced. The only major consequence is extraordinarily yellow skin.

Phenobarbital treatment can improve bilirubin glucuronidation .

Gilbert syndrome is a relatively common, benign, inherited condition presenting with mild,

fluctuating hyperbilirubinemia, in the absence of hemolysis or liver disease. It affects 3% to 10%

of the U.S. population. The mild hyperbilirubinemia may go undiscovered for years. When

detected in adolescence or adult life it is typically in association with stress, such as an intercurrent

illness, strenuous exercise, or fasting. Individuals who have Gilbert syndrome may be more

susceptible to adverse effects of drugs that are metabolized by UGT1A1.

Dubin-Johnson syndrome is an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by chronic

conjugated hyperbilirubinemia. It is caused by a defect in hepatocellular excretion of bilirubin

glucuronides across the canalicular membrane. The liver is darkly pigmented because of coarse

pigmented granules within the cytoplasm of hepatocytes . The liver is otherwise normal. Apart

from chronic or recurrent jaundice of fluctuating intensity, most patients are asymptomatic and

have a normal life expectancy.

Cholestasis

It is a pathologic condition of impaired bile formation and bile flow, leading to accumulation of

bile pigment in the hepatic parenchyma. It can be caused by:

-extrahepatic or intrahepatic obstruction of bile channels, or by

-defects in hepatocyte bile secretion.

Patients may have jaundice, pruritus, skin xanthomas (focal accumulation of cholesterol), or

symptoms related to intestinal malabsorption, including nutritional deficiencies of the fat-soluble

vitamins A, D, or K.

-A characteristic laboratory finding is elevated serum alkaline phosphatase and γ-glutamyl

transpeptidase (GGT) enzymes.

Morphology.

- accumulation of bile pigment within the hepatic parenchyma.

-Elongated green-brown plugs of bile are visible in dilated bile canaliculi.

-Rupture of canaliculi leads to extravasation of bile, which is quickly phagocytosed by Kupffer

cells.

-Droplets of bile pigment also accumulate within hepatocytes, which can take on a fine, foamy

appearance (feathery degeneration).

Extrahepatic biliary obstruction is frequently amenable to surgical alleviation. In contrast,

intrahepatic cholestasis is not benefited by surgery (short of transplantation), and the patient's

condition may be worsened by an operative procedure.

6

Infectious Disorders of liver

VIRAL HEPATITIS

Unless otherwise specified, the term viral hepatitis is applied for hepatic infections caused by a

group of viruses known as hepatotropic virus (hepatitis viruses A, B, C, D, and E) that have a

particular affinity for the liver.

TABLE -- The Hepatitis Viruses

Virus

Hepatitis A

Hepatitis B

Hepatitis C

Hepatitis D

Hepatitis E

Type of virus SsRNA

partially

dsDNA

ssRNA

Circular

defective ssRNA

ssRNA

Viral family

Hepatovirus;

related

to

picornavirus

Hepadnavirus

Flaviridae

Subviral particle

in

Deltaviridae

family

Calicivirus

Route

of

transmission

Fecal-oral

(contaminated

food or water)

Parenteral,

sexual contract,

perinatal

Parenteral;

intranasal

cocaine use is

a risk factor

Parenteral

Fecal-oral

Mean

incubation

period

2–4 weeks

1–4 months

7–8 weeks

Same as HBV

4–5 weeks

Frequency of

chronic liver

disease

Never

10%

∼80%

5% (coinfection);

≤70%

for

superinfection

Never

Diagnosis

Detection

of

serum

IgM

antibodies

Detection

of

HBsAg

or

antibody

to

HBcAg

PCR for HCV

RNA;

3rd-

generation

ELISA

for

antibody

detection

Detection of IgM

and

IgG

antibodies; HDV

RNA

serum;

HDAg in liver

PCR for HEV

RNA;

detection

of

serum

IgM

and

IgG

antibodies

Hepatitis A Virus

Hepatitis A virus (HAV) is a benign, self-limited disease with an incubation period of 3 to 6

weeks. HAV does not cause chronic hepatitis or a carrier state and only rarely causes fulminant

hepatitis, so the fatality rate associated with HAV is about 0.1%.

HAV occurs throughout the world and is endemic in countries with substandard hygiene and

sanitation, where populations may have detectable antibodies to HAV by the age of 10 years.

Clinical disease tends to be mild or asymptomatic, and is rare after childhood.

Affected individuals have nonspecific symptoms such as fatigue and loss of appetite, and often

develop jaundice. Overall, HAV accounts for about 25% of clinically evident acute hepatitis

worldwide .

7

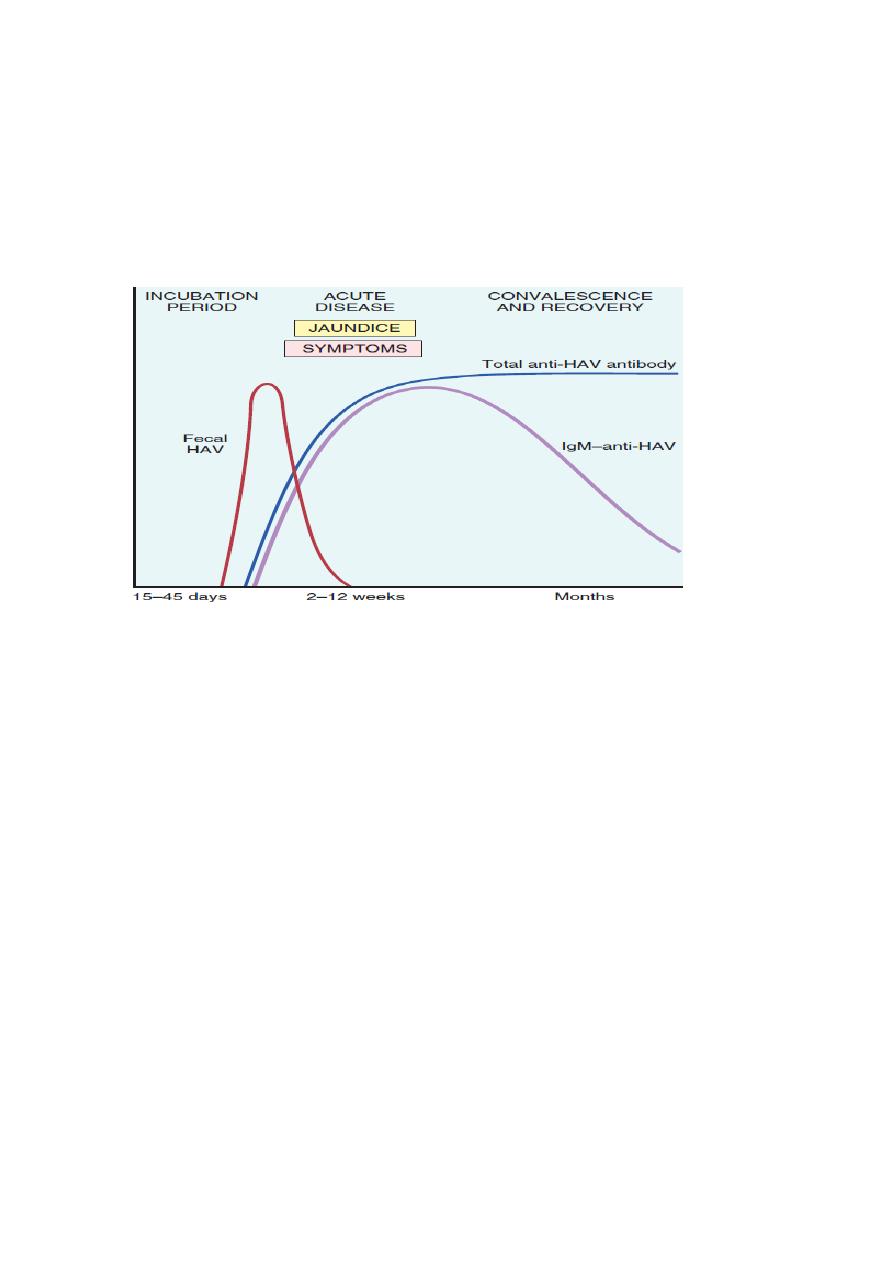

Specific IgM antibody against HAV appears in blood at the onset of symptoms, constituting a

reliable marker of acute infection ( Fig. below ). Fecal shedding of the virus ends as the IgM titer

rises. The IgM response usually begins to decline in a few months and is followed by the

appearance of IgG anti-HAV. The latter persists for years, perhaps conferring lifelong immunity

against reinfection by all strains of HAV. However, there are no routinely available tests for IgG

anti-HAV. The presence of this antibody is inferred from the difference between total and IgM

anti-HAV.

The sequence of serologic markers in acute hepatitis A infection

Hepatitis B Virus (HBV)

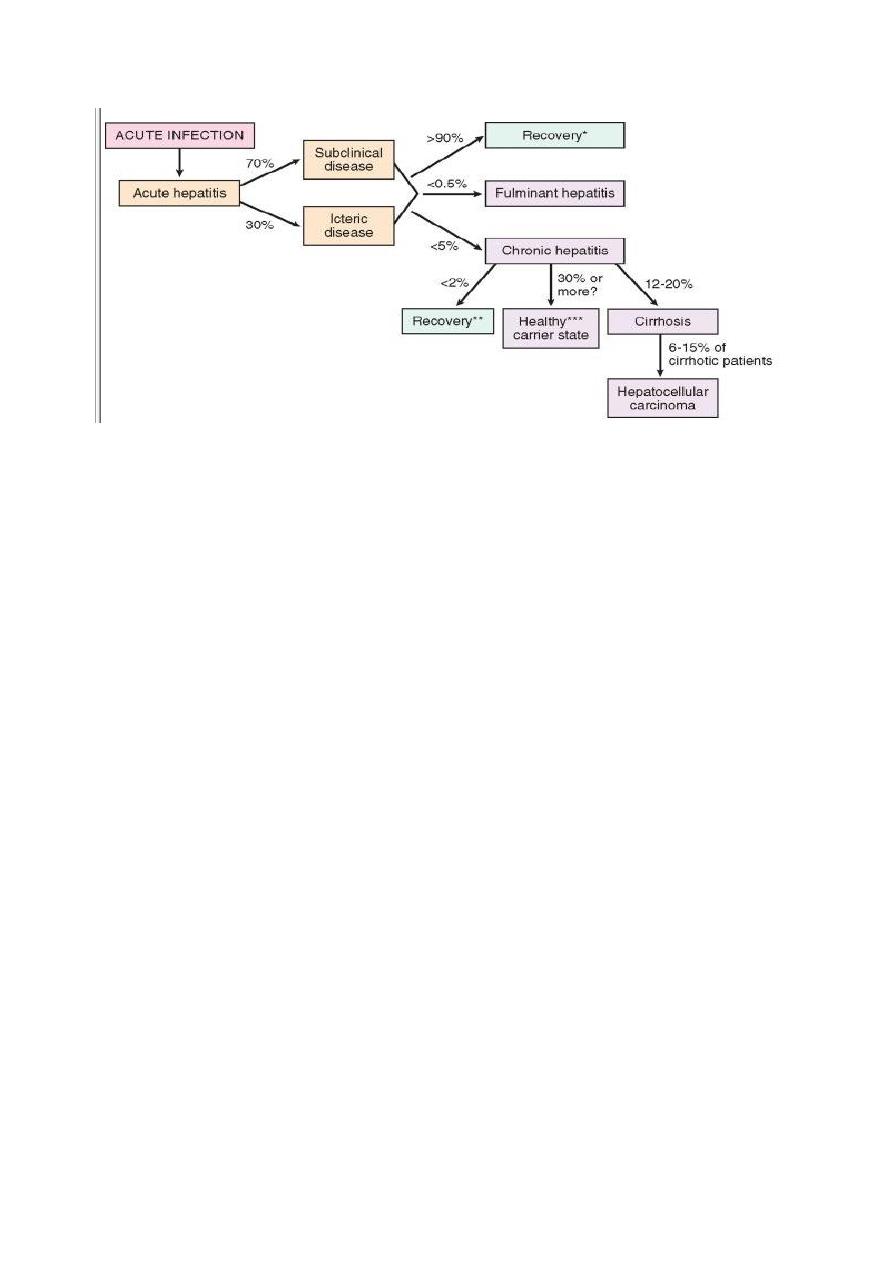

HBV can produce:

(1) acute hepatitis with recovery and clearance of the virus,

(2) nonprogressive chronic hepatitis,

(3) progressive chronic disease ending in cirrhosis,

(4) fulminant hepatitis with massive liver necrosis, and

(5) an asymptomatic carrier state.

HBV-induced chronic liver disease is an important precursor for the development of

hepatocellular carcinoma. The clinical outcomes of HBV infection are show in Figure below .

8

The potential outcomes with hepatitis B infection in adults

Liver disease due to HBV is an enormous global health problem. One third of the world

population (2 billion people) have been infected with HBV, and 400 million people have chronic

infection. The carrier rate is largely dictated by the age at infection, being the highest when

infection occurs in children perinatally and the lowest when adults are infected.

The mode of transmission of HBV occurs in different ways:

-perinatal transmission during childbirth .

-horizontal transmission (through minor cuts and breaks in the skin or mucous membranes among

children with close bodily contact),

-unprotected heterosexual or homosexual intercourse and intravenous drug abuse (sharing of

needles and syringes) .

The incidence of transfusion-related spread has decreased greatly in recent years due to screening

of donated blood.

Approximately 70% have mild or no symptoms and do not develop jaundice. The remaining 30%

have nonspecific constitutional symptoms such as anorexia, fever, jaundice, and upper right

quadrant pain. In almost all cases the infection is self-limited and resolves without treatment.

Chronic disease rarely occurs in adults in non-endemic areas. Fulminant hepatitis is also rare,

occurring in approximately 0.1 to 0.5% of cases.

The natural course of the disease can be followed by serum markers ( figure below).

9

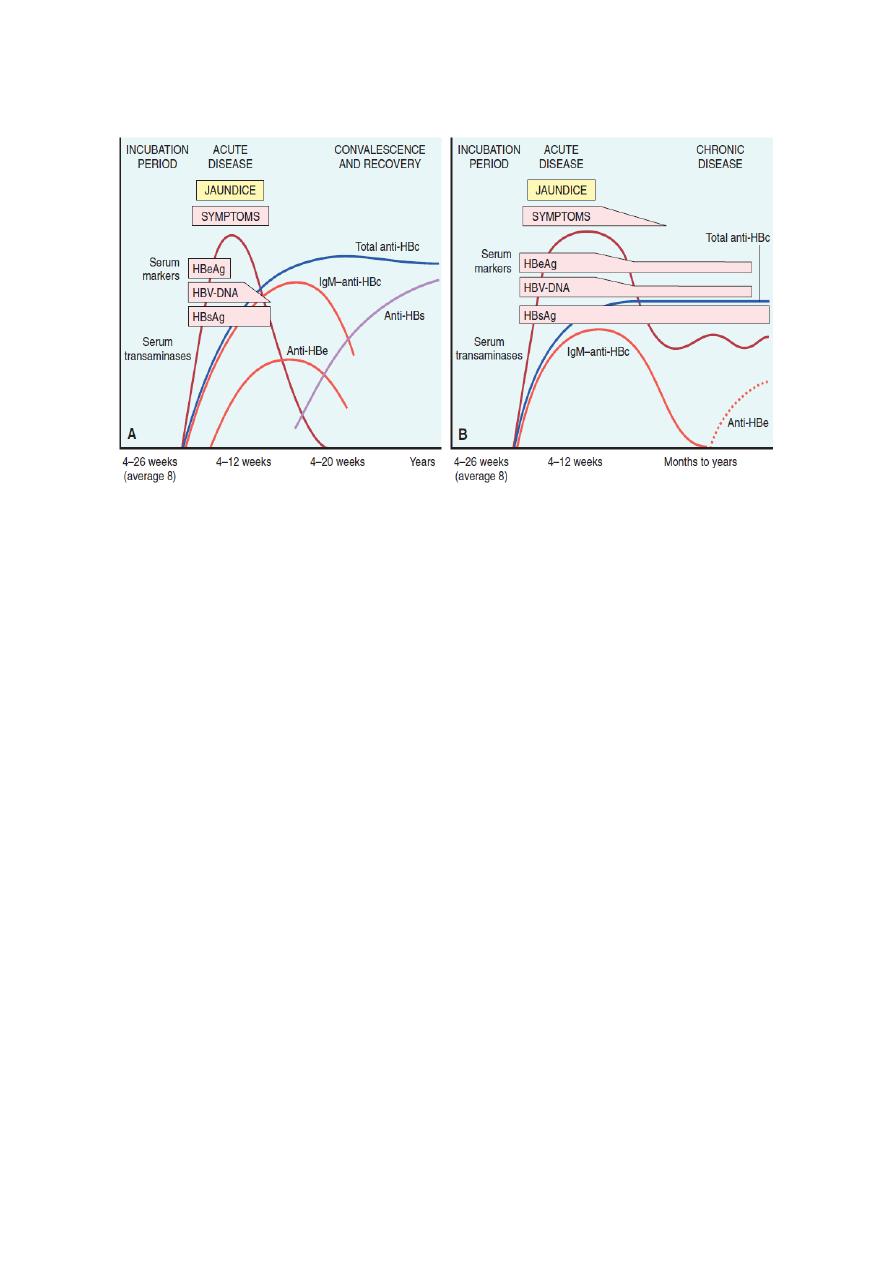

Sequence of serologic markers for hepatitis B viral hepatitis demonstrating (A) acute infection with resolution and

(B) progression to chronic infection

.

• HBsAg appears before the onset of symptoms, peaks during overt disease, and

then declines to undetectable levels in 3 to 6 months.

• Anti-HBs antibody does not rise until the acute disease is over and is usually not

detectable for a few weeks to several months after the disappearance of HBsAg.

• HBeAg, HBV-DNA, and DNA polymerase appear in serum soon after HBsAg,

and all signify active viral replication. Persistence of HBeAg is an important

indicator of continued viral replication, infectivity, and probable progression to

chronic hepatitis. The appearance of anti-HBe antibodies implies that an acute

infection has peaked and is on the wane.

• IgM anti-HBc becomes detectable in serum shortly before the onset of symptoms,

concurrent with the onset of elevated serum aminotransferase levels (indicative of

hepatocyte destruction). Over a period of months the IgM anti-HBc antibody is

replaced by IgG anti-HBc.

Hepatitis B can prevented by vaccination and by the screening of donor blood, organs, and tissues.