canine

Aetiology of maxillary canine displacement

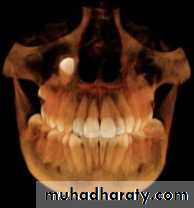

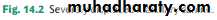

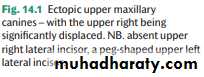

Canine displacement is generally classified into buccal or palatal displacement. More rarely, canines can be found lying horizontally above the apices of the teeth of the upper arch ( Fig. 14.1 ) or displaced high adjacent to the nose ( Fig. 14.2 ).The aetiology of canine displacement is still not fully understood.

• The following have been suggested as possible causative factors:

• Displacement of the crypt.• This is the probable aetiology behind the more marked displacements such as those shown in Figs 14.1 and 14.2.

2. Long path of eruption.

3. Short-rooted or absent upper lateral incisor.

A 2.4-fold increase in the incidence of palatally displaced canines in patients with absent or short-rooted lateral incisors has been reported ( Fig. 14.1 ). It has been suggested that a lack of guidance*during eruption is the reason behind this association. Because of the association of palatal displacement of an upper canine with missing or peg-shaped lateral incisors it is important to be particularly observant in patients with this anomaly.• 4. Crowding.

• Jacoby (1983) found that 85 per cent of buccally displaced canines were associated with crowding, whereas 83 per cent of palatal displacements had sufficient space for eruption. If the upper arch is crowded, this often manifests as insufficient space for the canine, which is the last tooth anterior to the molar to erupt. In normal development the canine comes to lie buccal to the arch and in the presence of crowding will be deflected buccally.5. Retention of the primary deciduous canine. This usually results in mild displacement of the permanent tooth buccally. However, if the permanent canine itself is displaced, normal resorption of the deciduous canine will not occur.

6. Genetic factors.

It has been suggested that palatal displacement of the maxillary canine is an inherited trait. The evidence cited for this includes:(a) the prevalence varies in different populations with a greater prevalence in Europeans than other racial groups

(b) affects females more commonly than males

(c) familial occurrence

(d) occurs bilaterally with a greater than expected frequency

(e) occurs in association with other dental anomalies

Interception of displaced canines

Because management of ectopic canines is difficult and early detection of an abnormal eruption path gives the opportunity, if appropriate, for interceptive measures, it is essential to routinely palpate for unerupted canines when examining any child aged 10 years and older.

Canines, which are palpable in the normal developmental position, which is buccal and slightly distal to the upper lateral incisor root, have a good prognosis for eruption. Clinically, if a definite hollow and/or asymmetry is found on palpation, further investigation is warranted. On occasion, routine panoramic radiographic examination may demonstrate asymmetry in the position and development of the canines.

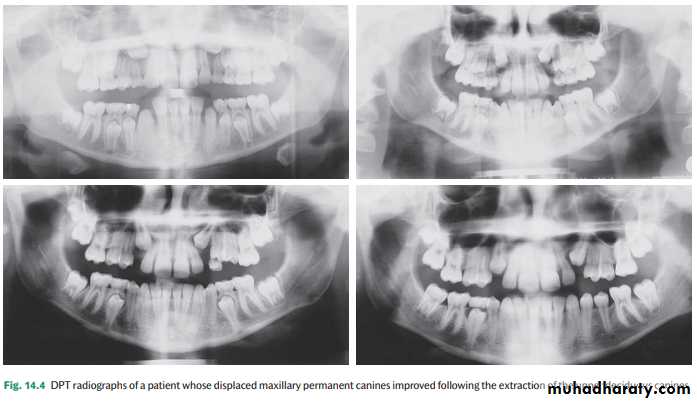

A number of studies have investigated the widely held belief that extraction of the deciduous canine facilitates an improvement in the position of a palatally displaced canine ( Fig. 14.4 ) where the unerupted tooth is not markedly ectopic.

Assessing maxillary canine position

The position of an unerupted canine should initially be assessed clinically, followed by radiographic examination if displacement is suspected.1 .Clinically

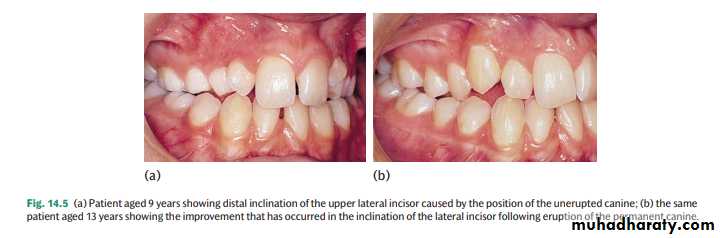

It is usually possible to obtain a good estimate of the likely location of an unerupted maxillary canine by palpation (in the buccal sulcus and palatally) and by the inclination of the lateral incisor ( Fig. 14.5 ).

2. Radiographically

The radiographic assessment of a displaced canine should include the following:• location of the position of both the canine crown and the root apex relative to adjacent teeth and the arch;

• the prognosis of adjacent teeth and the deciduous canine, if present;

• the presence of resorption, particularly of the adjacent central and/or lateral incisors.

The views commonly used for assessing ectopic canines include the following.

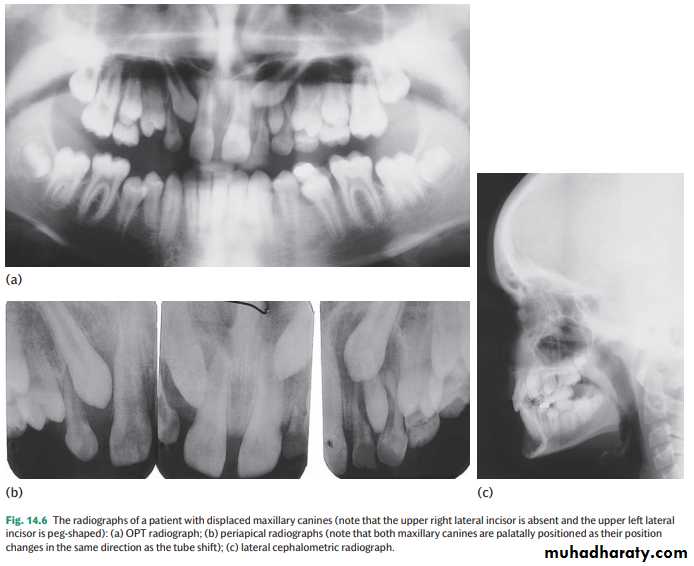

• Dental panoramic tomogram (OPG or DPT).This film gives a good overall assessment of the development of the dentition and canine position. However, this view suggests that the canine is further away from the midline and at a slightly less acute angle to the occlusal plane, i.e. more favourably positioned for alignment, than is actually the case ( Fig. 14.6 a). This view should be supplemented with an intra-oral view.

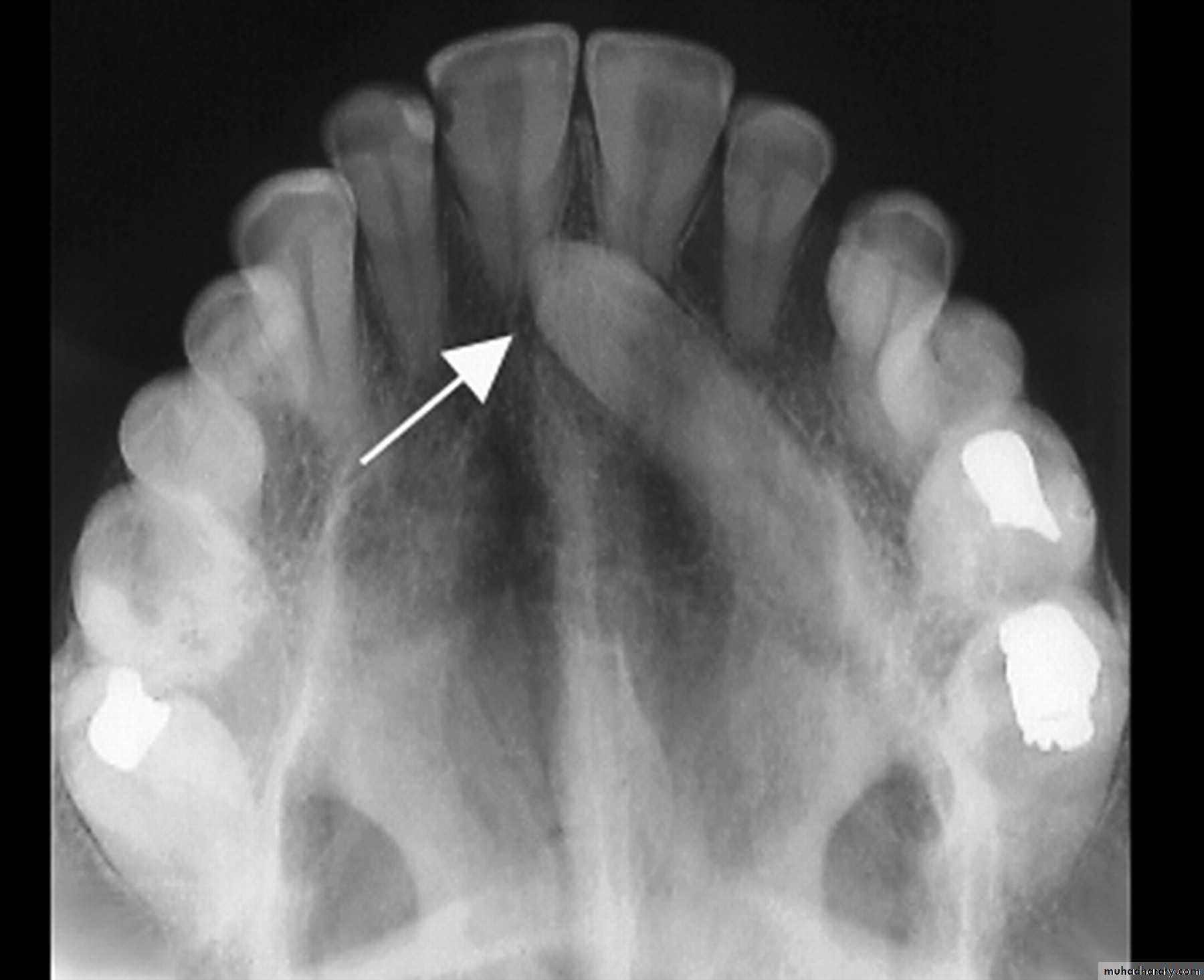

The principle of parallax can be used to determine the position of an unerupted tooth relative to its neighbours. To use parallax two radiographs are required with a change in the position of the X-ray tube between them. The object furthest away from the X-ray beam will appear to move in the same direction as the tube shift. Therefore, if the canine is more palatally positioned than the incisor roots it will move with the tube shift ( Fig. 14.6 b). Conversely, if it is buccal it will move in the opposite direction to the tube shift. Examples of combinations of radiographs which can be used for parallax include two periapical radiographs (horizontal parallax)

• Periapical.

This view is useful for assessing the prognosis of a retained deciduous canine and for detecting resorption ( Fig. 14.6 b).•Occlusal view x- ray.

• Lateral cephalometric.

For accurate localization this view should be combined with an anteroposterior view (e.g. an OPT) ( Fig. 14.6 c).• Cone beam computerized tomography (CBCT). Due to the increased radiographic dose, most orthodontists restrict CBCT to those ectopic canines where accurate localization has not been possible with conventional views and/or root resorption of adjacent teeth is suspected (see Fig. 5.17 ).

Management of buccal displacement

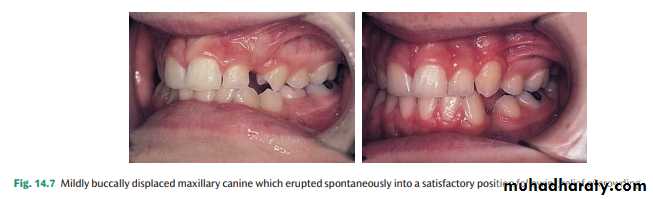

Buccal displacement is usually associated with crowding, and therefore relief of crowding prior to eruption of the canine will usually

effect some spontaneous improvement ( Fig. 14.7 ). Buccal displacements are more likely to erupt than palatal displacements because of the thinner buccal mucosa and bone

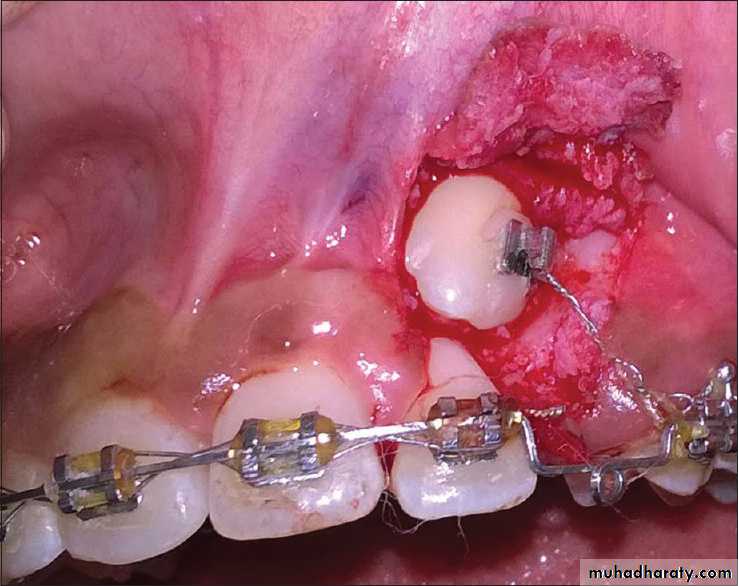

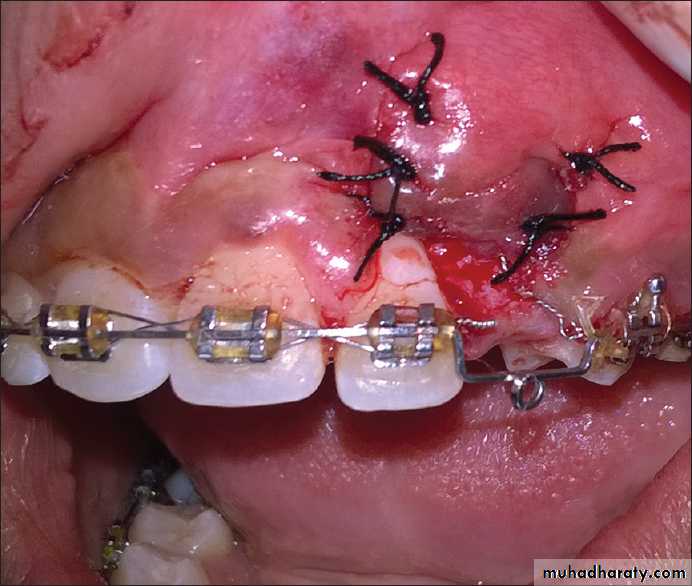

More rarely a buccally displaced canine tooth does not erupt or its eruption is so delayed that treatment for other aspects of the malocclusion is compromised. In these situations exposure of the impacted tooth may be indicated. To ensure an adequate width of attached gingiva either an apically repositioned or, preferably, a replaced flap should be used. In the latter case, in order to be able to apply traction to align the canine, an attachment can be bonded to the tooth at the time of surgery. A gold chain or a stainless steel ligature can be attached to the bond or band and used to apply traction.

In severely crowded cases where the upper lateral incisor and first premolar are in contact and no additional space exists to accommodate the wider canine tooth, extraction of the canine itself may be indicated.

In some patients the canine is so severely displaced that a good result is unlikely, necessitating removal of the canine tooth and the use of fixed appliances to close any residual spacing.

Management of palatal displacement

The treatment options available are as follows

1. Surgical removal of canine This option can be considered under the following conditions:

• The retained deciduous canine has an acceptable appearance and the patient is happy with the aesthetics and/or reluctant to embark on more complicated treatment ( Fig. 14.8 ). The clinician must ensure that the patient understands that the primary canine will be lost eventually and a prosthetic replacement required.

• The upper arch is very crowded and the upper first premolar is adjacent to the upper lateral incisor. Provided that the first premolar is not mesiopalatally rotated, the aesthetic result can be acceptable ( Fig. 14.9 ).

• The canine is severely displaced. Depending upon the presence of crowding and the patient’s wishes, either any residual spacing can be closed orthodontically or by prosthetic replacement.

2. Surgical exposure and orthodontic alignment Indications are as follows:

• well-motivated patient• well-cared-for dentition

• favourable canine position

• space available (or can be created)

Whether orthodontic alignment is feasible or not depends upon the three-dimensional position of the unerupted canine:

• Height: the higher a canine is positioned relative to the occlusal plane the poorer the prognosis. In addition, the access for surgical exposure will be more restricted. If the crown tip is at or above the apical third of the incisor roots, orthodontic alignment will be very difficult.

• Anteroposterior position: the nearer the canine crown is to the midline, the more difficult alignment will be. Most operators regard canines, which are more than halfway across the upper central incisor to be outside the limits of orthodontics.

• Position of the apex: the further away the canine apex is from normal, the poorer the prognosis for successful alignment. If it is distal to the second premolar, other options should be considered.

• Inclination: the smaller the angle with the occlusal plane the greater the need for traction.

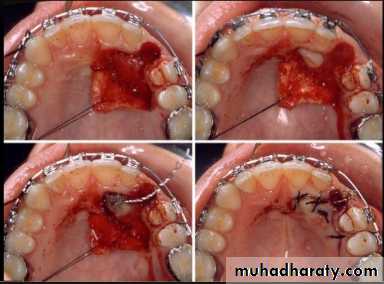

If these factors are favourable, the usual sequence of treatment is as follows:

• (1) Make space available (although some operators are reluctant to embark on permanent extractions until after the tooth has been exposed and traction successfully started).

• (2) Arrange exposure.

• (3) Allow the tooth to erupt for 2 to 3 months.

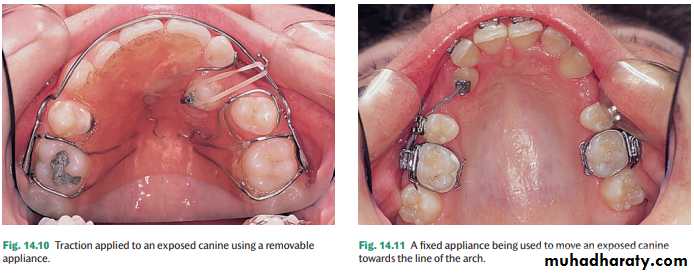

• (4) Commence traction. Traction can be applied using either a removable appliance ( Fig. 14.10 ) or a fixed appliance ( Fig. 14.11 ). To complete alignment a fixed appliance is necessary, as movement of the root apex buccally is required to complete positioning of the canine into a functional relationship with the lower arch.

• With deeply buried canines there is a danger that the gingivae may cover the tooth again. If this is likely to be a problem, either an attachment plus the means of traction (for example a wire ligature or gold chain) can be bonded to the tooth at the time of exposure or about 2 days after pack removal

Transplantation

Transplantation should be carried out when the canine root is two-thirds to three-quarters of itsfinal length; unfortunately, by the time most ectopic canines are diagnosed root development is further advanced. If transplantation is to be attempted, it must be possible to remove the canine intact and there must be space available to accommodate the canine within the arch and occlusion. In some cases this will mean that some orthodontic treatment will be required prior to transplantation.

The main causes of failure of transplanted canines are:

• Replacement resorption, or ankylosis, occurs when the root surface is damaged during the surgical procedure and is promoted by rigid splinting of the transplanted tooth, which encourages healing by bony rather than fi brous union.

• Inflammatory resorption follows death of the pulpal tissues, and therefore the vitality of the transplanted tooth must be carefully monitored.

Transposition

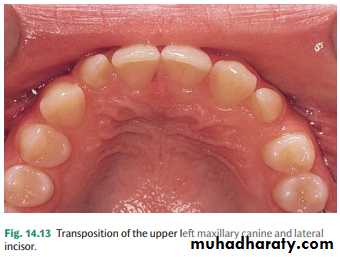

Transposition is the term used to describe interchange in the position of two teeth. This anomaly is comparatively rare, but almost always affects the canine tooth. It affects males and females equally and is more common in the maxilla.In the upper arch the canine and the first premolar are most commonly involved; however, transposition of the canine and lateral incisor is also seen ( Fig. 14.13 ). In the mandible the canine and lateral incisor appear to be almost exclusively affected

Possible treatment options include:

• acceptance (particularly if transposition is complete)• extraction of the most displaced tooth if the arch is crowded

• orthodontic alignment

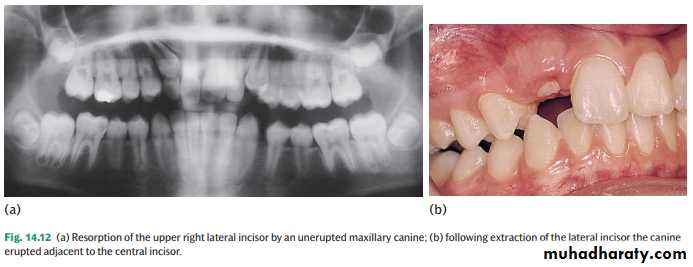

Resorption

Unerupted and impacted canines can cause resorption of adjacent lateral incisor roots and may sometimes progress to cause resorption of the central incisor. The increasing use of CBCT has shown that the prevalence of root resorption is greater than previously thought. A recent study indicated that two-thirds of upper lateral incisors associated with ectopic canines showed signs of resorption.Intervention is essential, as resorption often proceeds at a rapid rate. If it is discovered on radiographic examination, specialist advice should be sought quickly. Extraction of the canine may be necessary to halt the resorption. However, if the resorption is severe it may be wiser to extract the affected incisor(s), thus allowing the canine to erupt ( Fig. 14.12 ).