Pleural effusion

Assistant prof.Dr.Ahmed Hussein Jasim F.I.B.M.S (resp)

A pleural effusion results from the accumulation of abnormal volumes (>10–20mL)

of fluid in the pleural space.

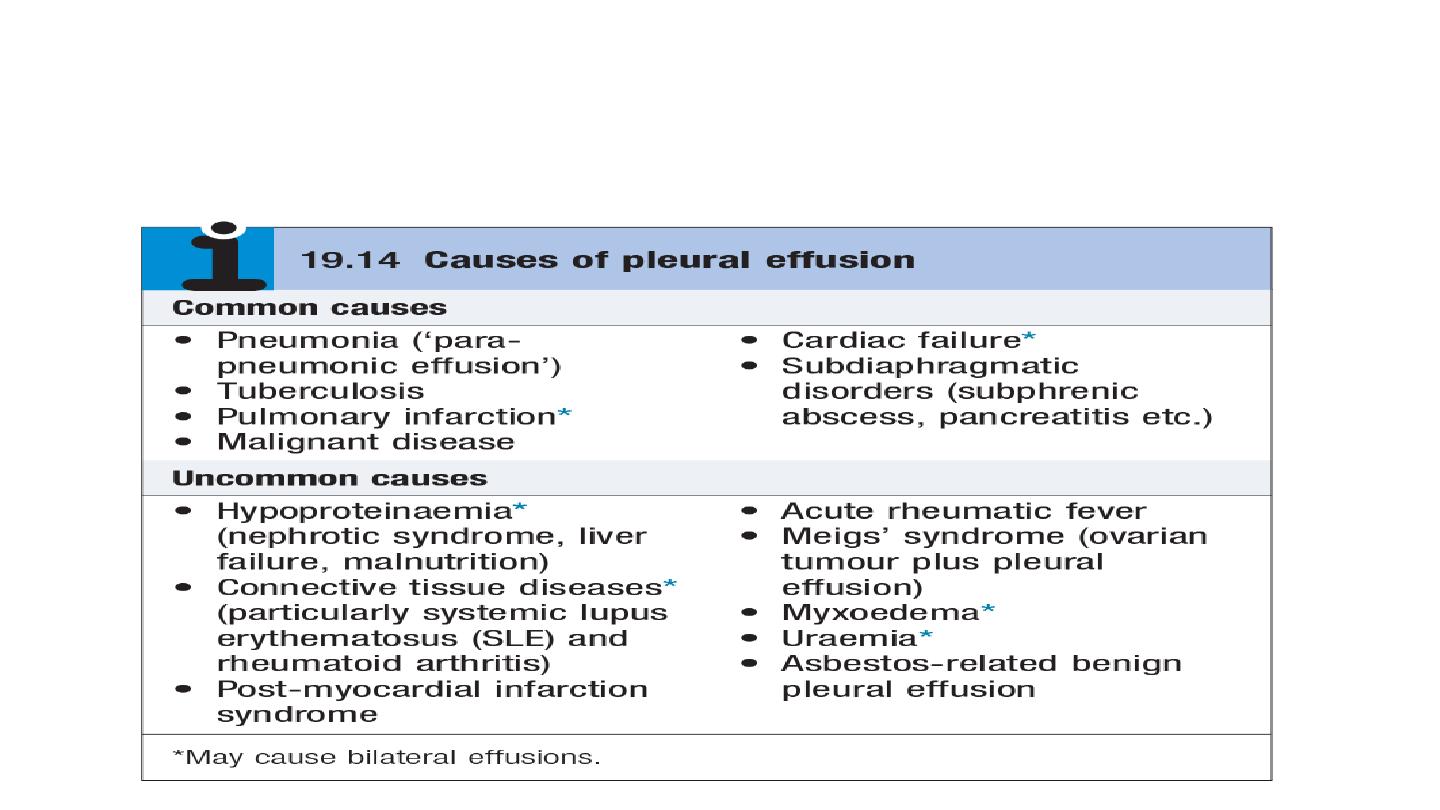

Commonest causes in the UK and US (in order): cardiac failure, pneumonia,

malignancy, PE.

Clinical features

May be asymptomatic or associated with breathlessness, dry cough, pleuritic chest

pain (suggesting pleural inflammation), chest ‘heaviness’, and sometimes pain

referred to the shoulder or abdomen

signs on examination include reduced chest expansion, reduced tactile vocal

fremitus, a stony dull percussion note, quiet breath sounds, and sometimes a patch

of bronchial breathing above the fluid level. a friction rub may be heard with

pleural inflammation.

Imaging

CXR

• Sequential blunting of posterior, lateral, and then anterior costophrenic angles are seen

on radiographs as effusions increase in size

• PA CXr will usually detect effusion volumes of 200mL or more; lateral CXr is more

sensitive and may detect as little as 50mL pleural fluid

• Classical CXr appearance is of basal opacity obscuring hemidiaphragm, with concave

upper border.

US has a much higher sensitivity than CXr at detecting and localizing pleural fluid and

is useful for distinguishing pleural fluid from pleural masses or thickening.

CT chest with pleural contrast is useful in distinguishing benign and malignant pleural

disease:

nodular, mediastinal, or circumferential pleural thickening and parietal

pleural thickening >1cm are all highly specific for malignant disease.

scans are best

performed prior to complete drainage of fluid

Role of MRI is unclear; it may have increasing role in distinguishing benign from

malignant pleural disease.

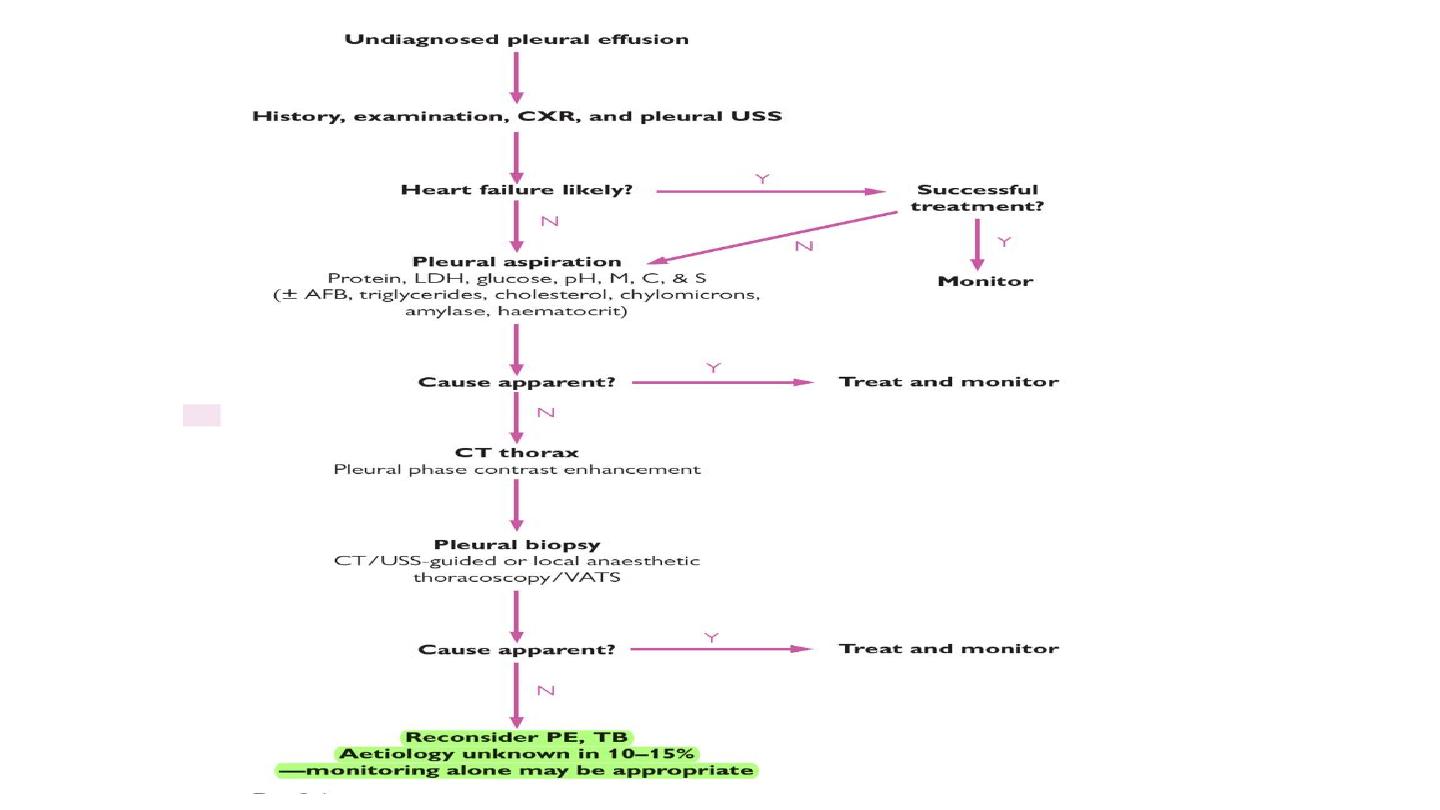

Thoracentesis (= ‘pleural tap’ or pleural fluid aspiration) may be diagnostic and/or

therapeutic, depending on the volume of fluid removed.

Following diagnostic tap: • note pleural fluid appearance

• Send sample to biochemistry for measurement of glucose, protein, and lactate

dehydrogenase (LDH)

• Send a fresh 20mL sample in sterile pot to cytology for examination for malignant

cells (yield 60% in malignancy) and differential cell count • Send samples in sterile

pot to microbiology for Gram stain and microscopy, culture. For suspected pleural

infection, also send pleural

fluid in blood culture bottles. Low threshold for AFB stain and tB culture

• Process non-purulent, heparinized samples in ABG analyser for pH

• Consider measurement of cholesterol, triglycerides, chylomicrons, haematocrit,

adenosine deaminase, and amylase, depending on the clinical circumstances.

Is the pleural effusion a transudate or an exudate? Helpful in narrowing the

differential diagnosis. In patients with a normal serum protein, pleural fluid

protein <30g/L = transudate, and protein >30g/L = exudate. In borderline cases

(protein 25–35g/L) or in patients with abnormal serum protein,

apply Light’s

criteria—effusion is exudative if it meets one of following criteria.

• Pleural fluid protein/serum protein ratio >0.5

• Pleural fluid LDH/serum LDH ratio >0.6

• Pleural fluid LDH > two-thirds the upper limit of normal serum LDH

Pleural tissue biopsy for histology and tB culture using image-guided or thoracoscopic

biopsies.

Parapneumonic effusion and empyema

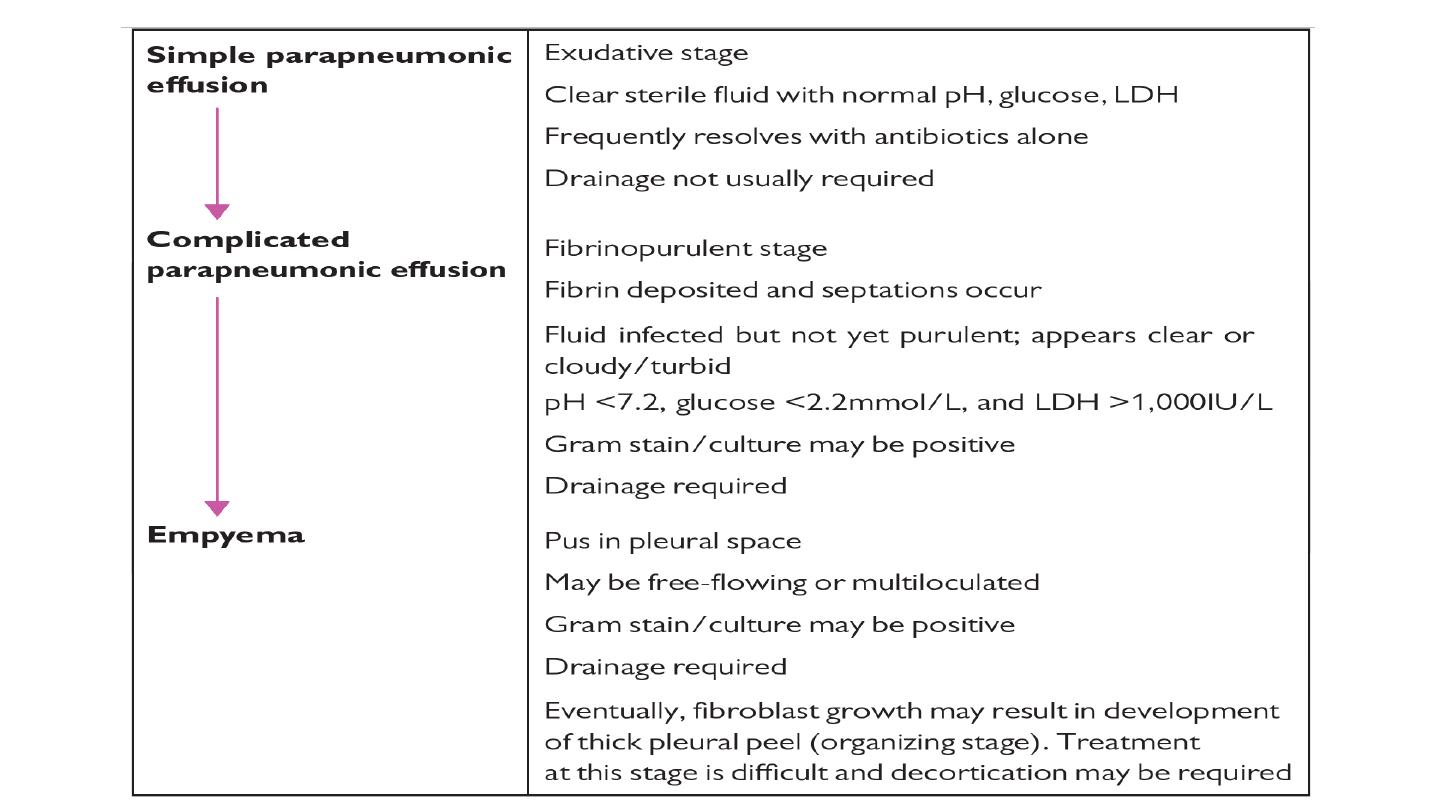

Definition and pathophysiology pleural effusions occur in up to 57% of patients with

pneumonia. an initial sterile exudate (simple parapneumonic effusion) may, in some

cases, progress to a complicated parapneumonic effusion and eventually empyema

pleural infection may also occur in the absence of a preceding pneumonic illness (‘

primary empyema’).

Clinical features

Consider the diagnosis particularly in cases of ‘slow-to-respond’ pneumonia (e.g.

failure of CRP to fall ≥50% in first 3 days), pleural effusion with fever, or high-risk

groups with non-specific symptoms such as weight loss ,

anaerobic empyema may

present less acutely, often with weight loss and without fever.

Risk factors for developing empyema include

diabetes, alcohol abuse, gastro-

oesophageal reflux, and IV drug abuse

. anaerobic infection is associated particularly

with aspiration or poor dental hygiene.

clinical variables associated with development of pleural infection in those with

pneumonia:

albumin <30g/L, CRP >100mg/L, platelets >400 × 10

9

/l, sodium

<130mmol/L, IVDU, and chronic alcohol use.

Bacteriology

Community-acquired infection (% of cases): •Streptococcus ‘milleri’ group (30%)

•anaerobes (5–30%) •Streptococcus pneumoniae (15%) •Staphylococcus

aureus (10%)

Hospital-acquired infection (% of cases): •MRSA (25-30%) •Staphylococcus aureus

(10–20%) • enterobacteriaceae (20%)

pleural infection is frequently polymicrobial.