Presenting problem in urinary system Lecture 5

Loin painDull ache in the loin is rarely due to renal disease but the differential diagnosis includes renal stone, renal tumour, acute pyelonephritis or urinary tract obstruction.

Renal colic

Acute loin pain radiating anteriorly and often to the groin (‘renal colic’), together with haematuria, is typical of ureteric obstruction most commonly due to calculi or ‘stones’, although a sloughed renal papilla,

tumour or blood clot may be responsible.

Urinary tract infection (UTI)

In health, bacterial colonisation is confined to the lower end of the urethra and the remainder of the urinary tract is sterile. UTI is the most common bacterial infection managed in general medical practice and accounts for 1–3% of consultations. Up to 50% of women have a UTI at some time. In males UTI is uncommon, except in the first year of life and in men over 60, in whom urinary tract obstruction due to prostatic hypertrophy may occur.

Symptoms and signs of UTI

The most typical symptoms of UTI are:

Frequency of micturition by day and night

Painful voiding (dysuria)

Suprapubic pain and tenderness

Haematuria

Smelly urine.

Abnormal micturition

Oliguria/anuria

On an average diet, between 300 and 500 mL/day of urine is required to excrete the solute load at maximum concentration. Volumes below this are termed oliguria.

Anuria is the (almost) total absence of urine (< 50 mL/day). A low measured urine volume is an important finding, as it suggests reduced production of urine or obstruction to urine flow.

Oliguria/anuria may be caused by a reduction in urine production, as typically seen in pre-renal acute renal failure, when GFR is reduced.

Urinary tract obstruction

The most common causes of lower urinary tract obstruction causing reduced volume of micturition are urinary calculi , prostatic enlargement (benign or malignant), or pelvic and retroperitoneal tumours in an older age group. About 50% of cases of acute urinary retention are seen after general anaesthesia, particularly in those with pre-existing prostatic enlargement.

Obstruction may be acute or chronic, and partial or complete. Acute obstruction is often associated with pain due to distension of the urinary tract that may be exacerbated by a fluid load. The site of the pain can indicate the site of the obstruction. Obstruction at the bladder neck (acute urinary retention) is associated with lower midline abdominal discomfort due to bladder dilatation. Ureteric obstruction, e.g. from a renal calculus, typically presents as loin pain radiating to the groin.

Higher obstructions, e.g. at the level of the renal pelvis, may present as flank pain. Chronic obstruction rarely produces pain but may produce a dull ache.

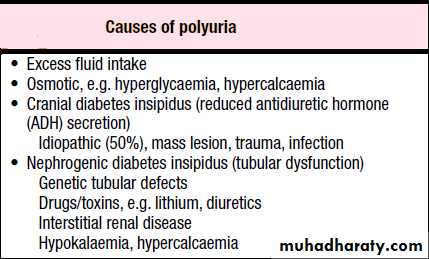

Polyuria

An inappropriately high urine volume (> 3 L/day) may result from increased urinary solute excretion (osmotic diuresis) or pure water diuresis . In primary (or psychogenic) polydipsia(increase water intake) , the increased urine output is an appropriate response to increased water intake; plasma sodium concentration is typically low– normal in such patients. In diabetes insipidus ,there is impaired urinary concentrating ability causing increased free water clearance (i.e. water free of solute); plasma sodium will usually be normal in such patients, since increased thirst will usually prevent high plasma sodium concentrations. However, restricted access to water may precipitate hypernatraemia.

Nocturia

Waking up at night to void urine may be a consequence of polyuria but may also result from fluid intake or diuretic use in the late evening. Nocturia also occurs in Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD), and in prostatic enlargement when it is associated with poor stream, hesitancy, incomplete bladder emptying, terminal dribbling and urinary frequency due to partial urethral obstruction . Nocturia may also occur in sleep disturbance without functional abnormalities of the urinary tract.Frequency

Frequency describes micturition more often than a patient’s expectations. It may be a consequence of polyuria, most commonly due to diuretic therapy, when volumes passed are normal or high. It is also a symptom of

UTIs (urethritis, cystitis, prostatitis) or urethral syndrome when urine volumes are typically low and associated with dysuria, urgency and a feeling of incomplete emptying.

Urinary incontinence

Urinary incontinence is defined as any involuntary leakage of urine.

It may also occur with a normal urinary tract, e.g. in association with poor cognition or poor mobility, or transiently during an acute illness or hospitalisation, especially in older people . Diuretics (medication, alcohol or caffeine) may worsen incontinence.

Urge incontinence is usually due to detrusor overactivity with leakage of urine because the bladder is perceived to be full.

Stress incontinence occurs when the intra-abdominal pressure is increased, e.g. after a cough or sneeze and there is a weak pelvic floor or urethral sphincter. It is common in women after childbirth.

Overflow incontinence occurs with leakage of urine from a full distended bladder. It occurs commonly in men with prostatic obstruction, following spinal cord injury or in women with cystoceles or after gynaecological surgery.

Haematuria

Haematuria may be visible and reported by the patient)macroscopic haematuria), or invisible and detected on dipstick testing of urine (microscopic haematuria(

It indicates bleeding from anywhere in the renal tract. Microscopy shows that normal individuals have occasional red blood cells (rbc) in the urine (up to12 500 rbc/mL). The detection limit for dipstick testing is 15–20 000 rbc/mL, which is sufficiently sensitive to detect all significant bleeding. However, dipstick tests are also positive in the presence of free haemoglobin or myoglobin.

Proteinuria

Moderate amounts of low molecular weight protein pass through the healthy Glomerular Basement membrane (GBM). These proteins are normally reabsorbed by receptors on tubular cells. Less than150 mg/day of protein normally appears in urine, and a proportion of that is Tamm–Horsfall protein secreted by the tubules.Relatively minor leakage of albumin into the urine may occur transiently after vigorous exercise, during fever or UTI, and in heart failure. Tests should be repeated once the stimulus is no longer present.

Oedema

Accumulation of interstitial fluid causes ‘pitting’ oedema, that leaves an indentation after pressure on the affected area. This results from disruption of the Starling forces dictating fluid transit across capillary basement membranes.

It is usually influenced by the effect of gravity on venous hydrostatic pressure and so accumulates in the ankles during the day and improves overnight (‘dependent’ oedema). Non-pitting oedema may reflect protein

deposition—for example, in myxoedema associated with hypothyroidism and also occurs in chronic abdomen, combined with testing the urine for protein and measuring the serum albumin level. Where ascites or pleural effusions in isolation are causing diagnostic difficulty, aspiration of fluid with measurement of protein and glucose, and microscopy for cells, will usually clarify the diagnosis.

Hypertension

Hypertension is avery common feature of renal disease, and a particularly early manifestation of renovascular and some glomerular diseases. Renal mechanisms seem to be important in essential hypertension , and most genetic disorders of blood pressure have been attributed to altered salt and water handling by the kidney.

In renal interstitial disorders, increased sodium loss (through reduced reabsorption from glomerular filtrate) may lead to hypotension. However, as GFR declines, hypertension becomes an increasingly common feature.

When renal function is replaced by dialysis, control of hypertension often becomes easier as salt and volume balance are controlled.

PRESENTING PROBLEMS IN BLOOD DISEASE Lecture 6

AnaemiaAnaemia refers to a state in which the level of haemoglobin in the blood is below the normal range appropriate for age and sex.

Other factors, including pregnancy and altitude, also affect haemoglobin levels and must be taken into account when considering whether an individual is anaemic. The clinical features of anaemia reflect diminished oxygen supply to the tissues. A rapid onset of anaemia (e.g. due to blood loss) causes more profound symptoms than a gradually developing anaemia.

Individuals with cardiorespiratory disease are more susceptible to symptoms of anaemia.

High haemoglobin

A haemoglobin level greater than the upper limit of normal (adult females 165 g/L or haematocrit > 0.48; adult males 180 g/L or haematocrit > 0.52) may be due to an increase in the number of red blood cells (true polycythaemia) or a reduction in the plasma volume (relative or apparent polycythaemia).

Circulating red cell mass is measured by radio-labelling an aliquot of the patient’s red cells with 51Cr, re-injecting the cells and measuring the dilution of the isotope. The plasma volume is measured by a similar dilution technique using albumin labelled with 125I.

Leucopenia (low white cell count)

A reduction in the total numbers of circulating white cells is called leucopenia. This may be due to a reduction in all types of white cell or in individual cell types (usually neutrophils or lymphocytes). Leucopenia may occur in isolation or as part of a reduction in all three haematological lineages (pancytopenia).

Leucocytosis (high white cell count)

An increase in the total numbers of circulating white cells is called leucocytosis. This is usually due to an increase in a specific type of cell . It is important to realise that an increase in a single type of white cell (e.g. eosinophils or monocytes) may not increase the total white cell count (WCC) above the upper limit of normal and will only be apparent if the

‘differential’ of the white count is examined.

Lymphadenopathy

Enlarged lymph glands may be an important indicator of haematological disease but they are not uncommon in reaction to infection or inflammation .

The sites of lymph node groups, and symptoms and signs that may help elucidate the underlying cause, Nodes which enlarge in response

to local infection or inflammation (reactive nodes(usually expand rapidly and are painful, whereas those due to haematological disease are more frequently painless. Localised lymphadenopathy should elicit a search for a source of inflammation in the appropriate drainage area:

• the scalp, ear, mouth, face or teeth for neck nodes

• the breast for axillary nodes

• the perineum or external genitalia for inguinal nodes.

Generalised lymphadenopathy may be secondary to infection, connective tissue disease or extensive skin disease, but is more likely to signify underlying haematological malignancy. Weight loss and drenching night

sweats which may require a change of night clothes are associated with haematological malignancies, particularly lymphoma.

Splenomegaly

The spleen is the largest lymphoid organ in the body and is situated in the left hypochondrium. There are two anatomical components:

The red pulp, consisting of sinuses lined by endothelial macrophages and cords (spaces)

The white pulp, which has a structure similar to lymphoid follicles.

Blood enters via the splenic artery and is delivered to the red and white pulp. During the flow the blood is ‘skimmed’, with leucocytes and plasma preferentially passing to white pulp. Some red cells pass rapidly through into the venous system while others are held up in the red pulp.

The spleen may be enlarged due to involvement by

lymphoproliferative disease

the resumption of extramedullary haematopoiesis in myeloproliferative disease,

enhanced reticulo-endothelial activity in autoimmune haemolysis,

expansion of the lymphoid tissue in response to infections

vascular congestion as a result of portal hypertension .

Hepatosplenomegaly is suggestive of lympho- or myeloproliferative disease, liver disease or infiltration (e.g. with amyloid). Associated

lymphadenopathy is suggestive of lymphoproliferative disease. An enlarged spleen may cause abdominal discomfort, accompanied by back pain and abdominal bloating due to stomach compression. Splenic infarction may occur and produces severe abdominal pain radiating

to the left shoulder tip, associated with a splenic rub on auscultation. Rarely, spontaneous or traumatic rupture and bleeding may occur.

Bleeding

Normal bleeding is seen following surgery and trauma.

Pathological bleeding occurs when structurally abnormal vessels rupture or when a vessel is breached in the presence of a defect in haemostasis. This may be due to a deficiency or dysfunction of platelets, the coagulation factors, or occasionally to excessive fibrinolysis, which is

most commonly observed following therapeutic thrombolysis .

It is important to consider the following points:

• Site of bleeding. Bleeding into muscle and joints, along with retroperitoneal and intracranial haemorrhage, indicates a likely defect in

coagulation factors. Purpura, prolonged bleeding from superficial cuts, epistaxis, gastrointestinal haemorrhage or menorrhagia is more likely to

be due to thrombocytopenia, a platelet function disorder or von Willebrand disease. Recurrent bleeds at a single site suggest a local structural abnormality.

• Duration of history. It may be possible to assess whether the disorder is congenital or acquired.

• Precipitating causes. Bleeding arising spontaneously indicates a more severe defect than bleeding that occurs only after trauma.

• Surgery. Ask about all operations. Dental extractions, tonsillectomy and circumcision are particularly stressful tests of the haemostatic system. Immediate post-surgical bleeding suggests defective platelet plug formation and primary haemostasis, while delayed haemorrhage is more suggestive of a coagulation defect. However, in post-surgical patients, persistent bleeding from a single site is more likely to indicate surgical bleeding than a bleeding disorder.

• Family history. While a positive family history may be present in patients with inherited disorders, the absence of affected relatives does not exclude a hereditary bleeding diathesis; about one-third of cases of haemophilia arise in individuals without a family history and deficiencies of factor VII, X and XIII are recessively inherited. Recessive disorders

are more common in cultures where there is consanguineous marriage.

• Drugs. Use of antithrombotic, anticoagulant and fibrinolytic drugs must be elicited. Drug interactions with warfarin and drug-induced thrombocytopenia should be considered. Some ‘herbal’ remedies may

result in a bleeding diathesis.

Thrombocytopenia (low platelet count)

A reduced platelet count may arise by one of two mechanisms:

• decreased or abnormal production (bone marrow failure and hereditary thrombocytopathies)

• increased consumption following release into the circulation (immune-mediated, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) or sequestration).

Spontaneous bleeding does not usually occur until the platelet count falls below 20 × 109/L, unless their function is also compromised. Purpura and spontaneous bruising are characteristic but there may also be oral, nasal, gastrointestinal or genitourinary bleeding. Severe thrombocytopenia

(< 10 × 109/L) may result in retinal haemorrhage and potentially fatal intracranial bleeding.

Thrombocytosis (high platelet count)

The most common reason for a raised platelet count is that it is reactive to another process such as infection ,connective tissue disease, malignancy, iron deficiency, acute haemolysis or gastrointestinal bleeding .The presenting clinical features are usually those of the underlying disorder and haemostasis is rarely affected. Reactive thrombocytosis is distinguished from the myeloproliferative disorders by the presence of uniform small platelets and lack of splenomegaly. The key to diagnosis is the clinical history and examination, combined with observation of the platelet count over time.

Pancytopenia

Pancytopenia refers to the combination of anaemia, leucopenia and thrombocytopenia. It may be due to reduced production of blood cells as a consequence of bone marrow suppression or infiltration, or there may

be peripheral destruction or splenic pooling of mature cells.

Infection

Infection is a major complication of haematological disorders.

The type of infection relates to the immunological deficit caused by the disease itself, or its treatment with chemotherapy and/or immunotherapy.

Venous thrombosis

While the most common presentation of venous thromboembolic

disease (VTE) is with deep vein thrombosis)DVT) of the leg and/or pulmonary embolism (PE), similar principles apply to rarer manifestations such as jugular vein thrombosis, upper limb DVT,

cerebral sinus thrombosis , and intra-abdominal

venous thrombosis (e.g. Budd–Chiari syndrome).