Endocrinology Dr Yasameen

Alsaffar

Lec 1

Introduction

Endocrinology concerns the synthesis, secretion and action of

hormones. These are chemical messengers released from endocrine

glands that coordinate the activities of many different cells.

Endocrine diseases can therefore affect multiple organs and systems.

Some endocrine disorders are common, particularly those of the

thyroid, parathyroid glands, reproductive system and β cells of the

pancreas.

Functional anatomy and physiology

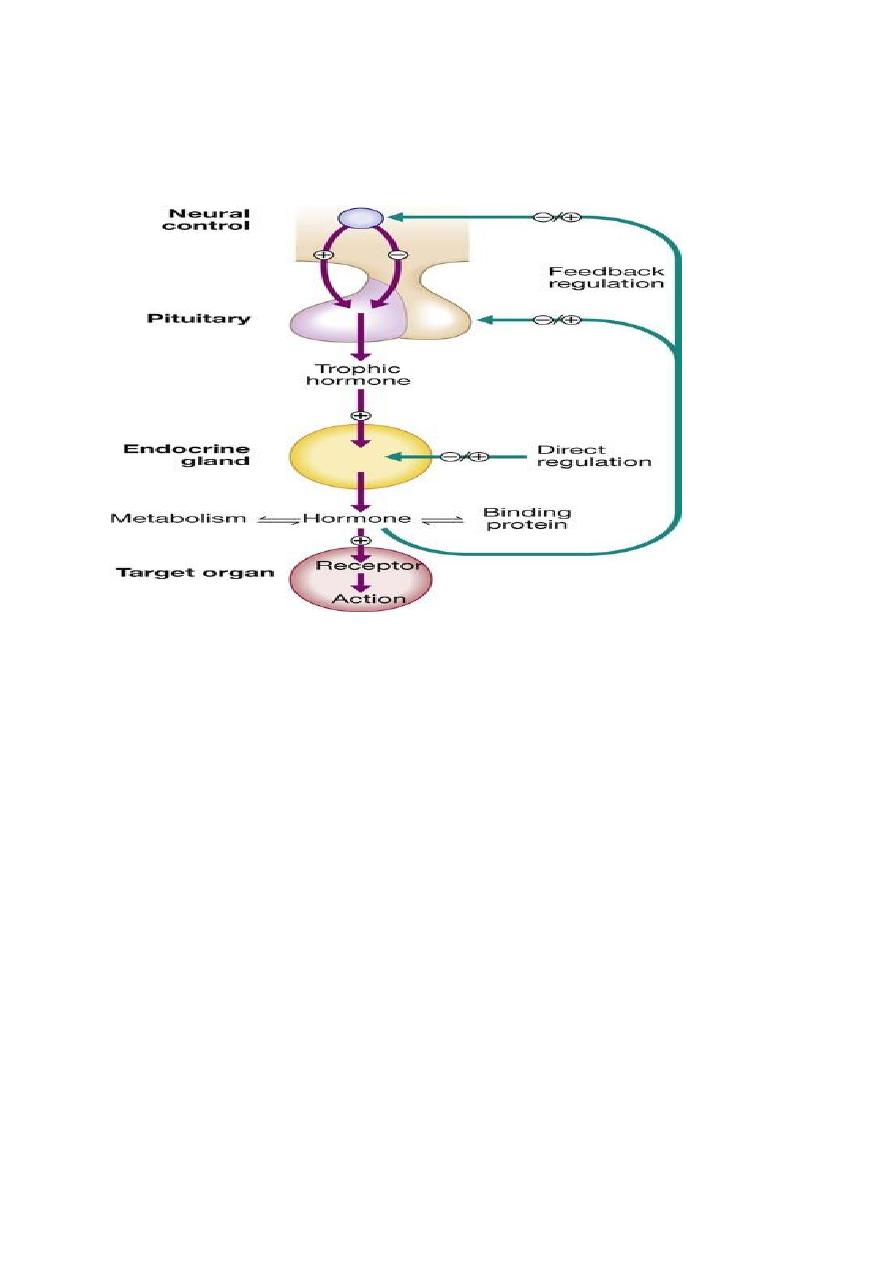

Some endocrine glands, such as the parathyroids and pancreas,

respond directly to metabolic signals, but most are controlled by

hormones released from the pituitary gland. Anterior pituitary

hormone secretion is controlled in turn by substances produced in

the hypothalamus and released into portal blood, which drains

directly down the pituitary stalk. Posterior pituitary hormones are

synthesised in the hypothalamus and transported down nerve axons,

to be released from the posterior pituitary. Hormone release in the

hypothalamus and pituitary is regulated by numerous stimuli and

through feedback control by hormones produced by the target

glands (thyroid, adrenal cortex and gonads). These integrated

endocrine systems are called ‘axes’.

A wide variety of molecules can act as hormones, including peptides

such as insulin and growth hormone, glycoproteins such as thyroid-

stimulating hormone, and amines such as noradrenaline

(norepinephrine). The biological effects of hormones are mediated

by binding to receptors. Many receptors are located on the cell

surface.

Endocrine pathology

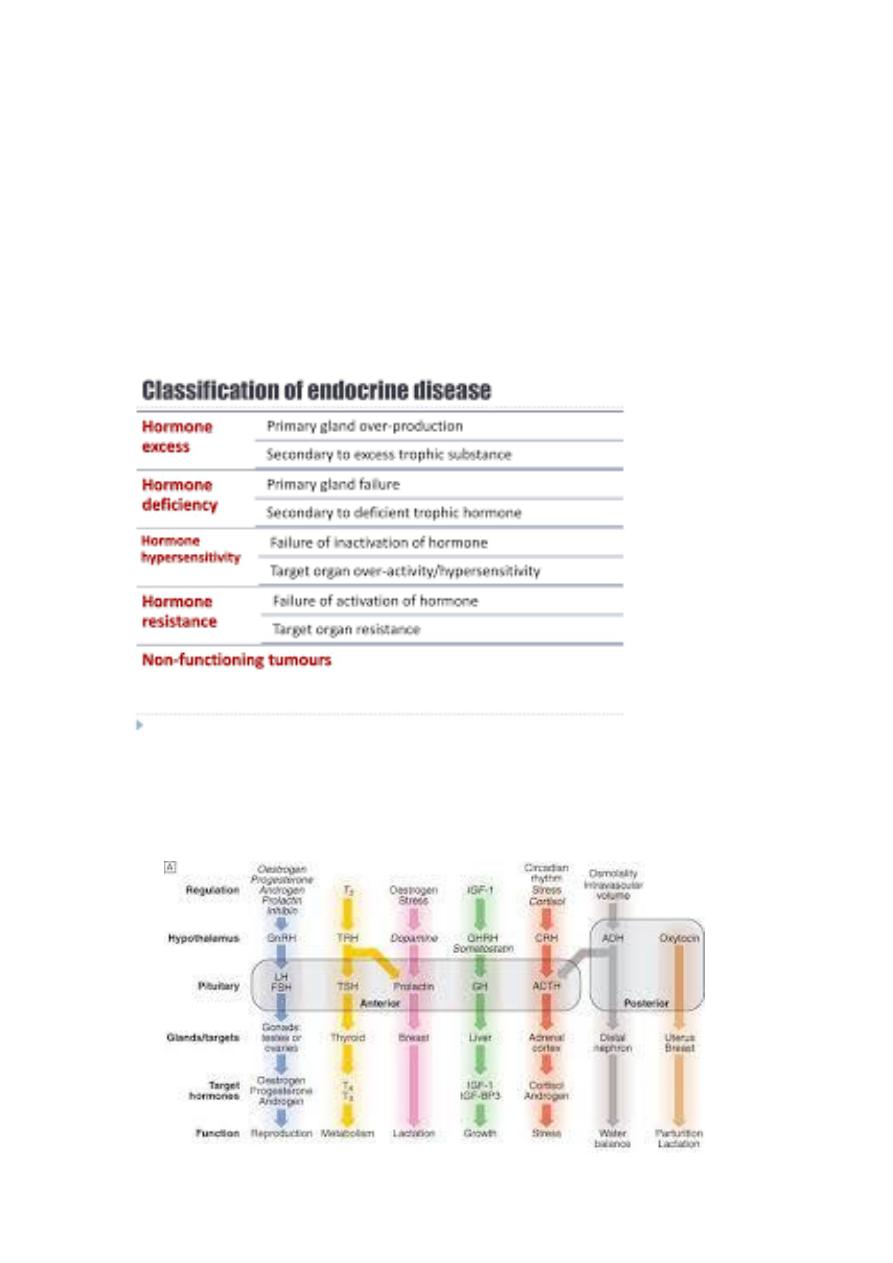

For each endocrine axis or major gland, diseases can be classified as

Pathology arising within the gland is often called ‘primary’ disease

(e.g. primary hypothyroidism in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis), while

abnormal stimulation of the gland is often called ‘secondary’ disease

(e.g. secondary hypothyroidism in patients with a pituitary tumour

and thyroid-stimulating hormone

deficiency). Some pathological

processes can affect multiple endocrine glands these may have a

genetic basis (such as organ-specific autoimmune endocrine

disorders and the multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) syndromes) or

be a consequence of therapy for another disease (e.g. following

treatment of childhood cancer with chemotherapy and/or

radiotherapy).

Classification

The principal endocrine ‘axes’. Some major endocrine glands are not controlled by the

pituitary. These include the parathyroid glands (regulated by calcium concentrations, p.

661), the adrenal zona glomerulosa (regulated by the renin–angiotensin system, p. 665) and

the endocrine pancreas. Italics show negative regulation. (ACTH = adrenocorticotrophic

hormone; CRH = corticotrophin-releasing hormone; FSH = folliclestimulating hormone; GH =

growth hormone; GHRH = growth hormone-releasing hormone; GnRH = gonadotrophin-

releasing hormone; IGF-1 = insulin-like growth factor-1; IGF-BP3 = IGF-binding protein-3; LH

= luteinising hormone: T3 = triiodothyronine; T4 = thyroxine; TRH = thyrotrophin-releasing

hormone; TSH = thyroid-stimulating hormone; vasopressin = antidiuretic hormone (ADH))

Investigation of endocrine disease

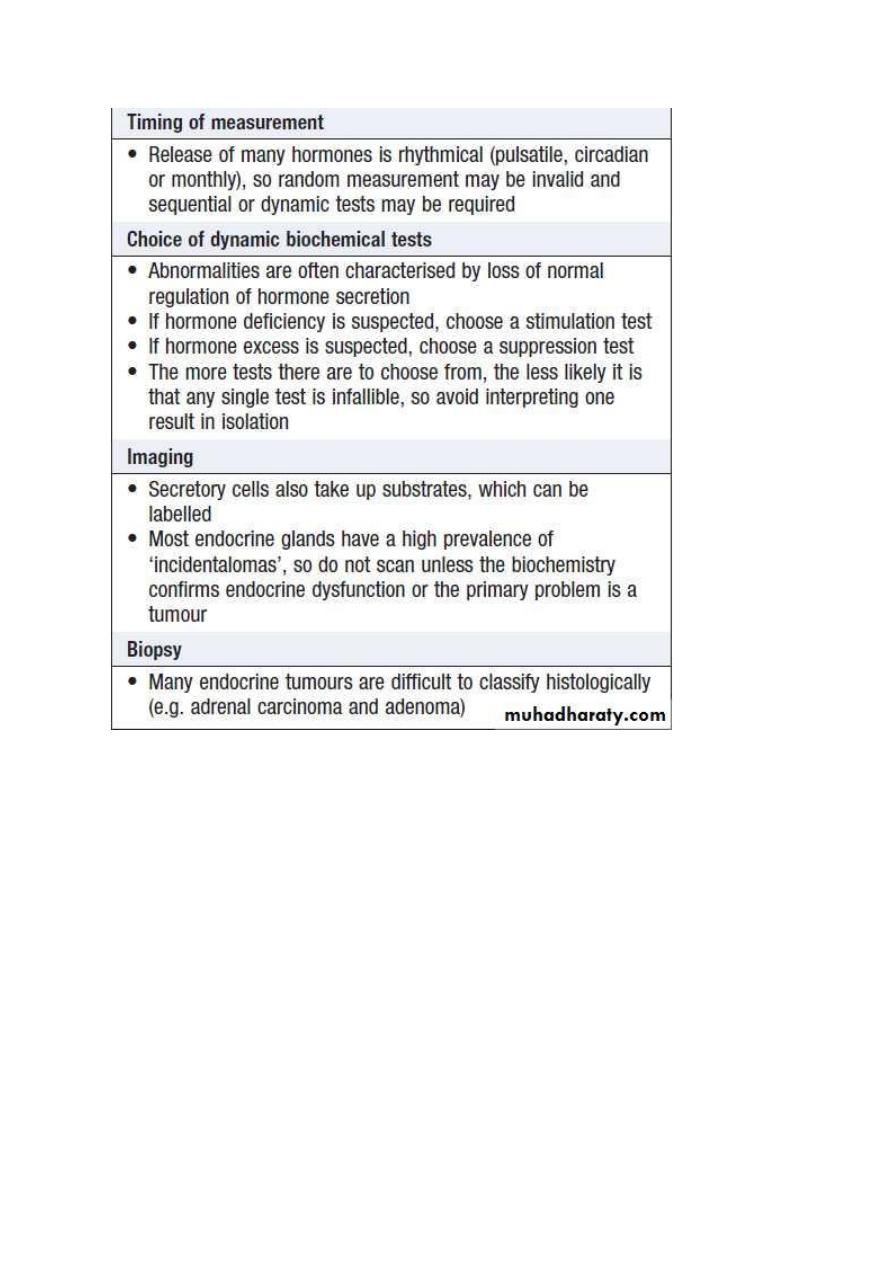

Biochemical investigations play a central role in endocrinology. Most

hormones can be measured in blood but the circumstances in which

the sample is taken are often crucial, especially for hormones with

pulsatile secretion, such as growth hormone; those that show diurnal

variation, such as cortisol; or those that demonstrate monthly

variation, such as oestrogen or progesterone. Some hormones are

labile and need special collection, handling and processing

requirements, e.g. collection in a special tube and/or rapid

transportation to the laboratory on ice. Local protocols for hormone

measurement should be carefully followed. Other investigations,

such as imaging and biopsy, are more frequently reserved for

patients who present with a tumour.

Examples of non-specific presentations of endocrine disease

Symptom

Most likely endocrine disorder(s)

1. Lethargy and depression Hypothyroidism, diabetes mellitus,

hyperparathyroidism, hypogonadism, adrenal insufficiency and

Cushing’s syndrome.

2. Weight gain Hypothyroidism, Cushing’s syndrome

3. Weight loss Thyrotoxicosis, adrenal insufficiency, diabetes

mellitus.

4. Polyuria and polydipsia Diabetes mellitus, diabetes insipidus,

hyperparathyroidism, hypokalaemia (Conn’s syndrome)

5. Heat intolerance Thyrotoxicosis, menopause

6. Palpitation Thyrotoxicosis, phaeochromocytoma

7. Headache Acromegaly, pituitary tumour, phaeochromocytoma

Muscle weakness (usually proximal) Thyrotoxicosis, Cushing’s

syndrome, hypokalaemia (e.g. Conn’s syndrome),

hyperparathyroidism, hypogonadism

8. Coarsening of features Acromegaly, hypothyroidism

Thank you