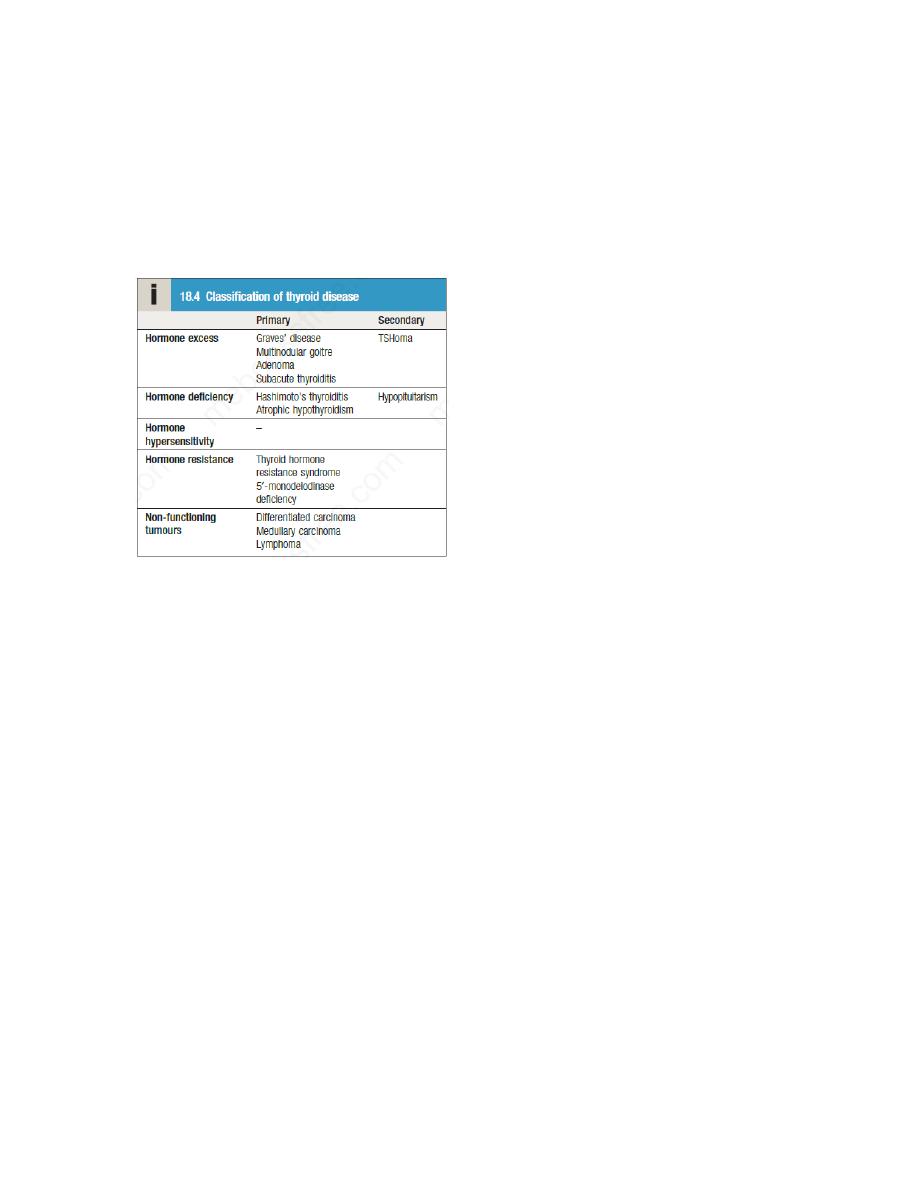

Thyroid gland

Diseases of the thyroid predominantly affect females and are common, occurring in about 5% of

the population. The thyroid axis is involved in the regulation of cellular differentiation and

metabolism in virtually all nucleated cells, so that disorders of thyroid function have diverse

manifestations. Structural diseases of the thyroid gland, such as goitre, commonly occur in

patients with normal thyroid function.

Functional anatomy, physiology

and investigations

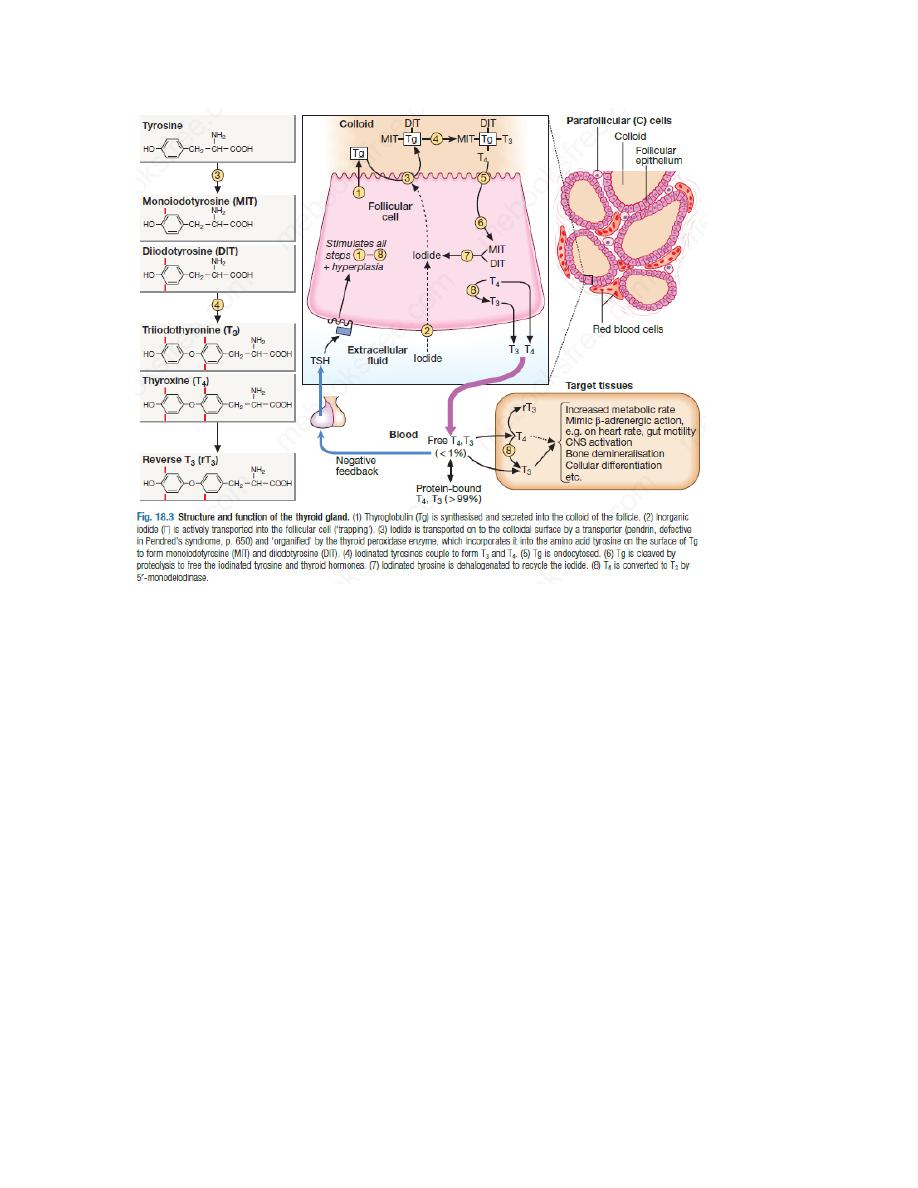

The parafollicular C cells secrete calcitonin, which is of no apparent physiological significance in

humans. The follicular epithelial cells synthesise thyroid hormones by incorporating iodine into

the amino acid tyrosine on the surface of thyroglobulin (Tg), a protein secreted into the colloid

of the follicle. Iodide is a key substrate for thyroid hormone synthesis; a dietary intake in excess

of 100 μg/day is required to maintain thyroid function in adults. The thyroid secretes

predominantly thyroxine (T4) and only a small amount of triiodothyronine (T3); approximately

85% of T3 in blood is produced from T4 by a family of monodeiodinase enzymes which are

active in many tissues, including liver, muscle, heart and kidney.

T4 can be regarded as a pro-hormone, since it has a longer half-life in blood than T3

(approximately 1 week compared with approximately 18 hours), and binds and activates thyroid

hormone receptors less effectively than T3. T4 can also be converted to the inactive metabolite,

reverse T3. T3 and T4 circulate in plasma almost entirely (> 99%) bound to transport proteins,

mainly thyroxine-binding globulin (TBG). It is the unbound or free hormones which diffuse into

tissues and exert diverse metabolic actions.

Production of T3 and T4 in the thyroid is stimulated by thyrotrophin (thyroid-stimulating

hormone, TSH), a glycoprotein released from the thyrotroph cells of the anterior pituitary in

response to the hypothalamic tripeptide, thyrotrophin-releasing hormone (TRH).

There is a negative feedback of thyroid hormones on the hypothalamus and pituitary such that

in thyrotoxicosis, when plasma concentrations of T3 and T4 are raised, TSH secretion is

suppressed. Conversely, in hypothyroidism due to disease of the thyroid gland, low T3 and T4

are associated with high circulating TSH levels.

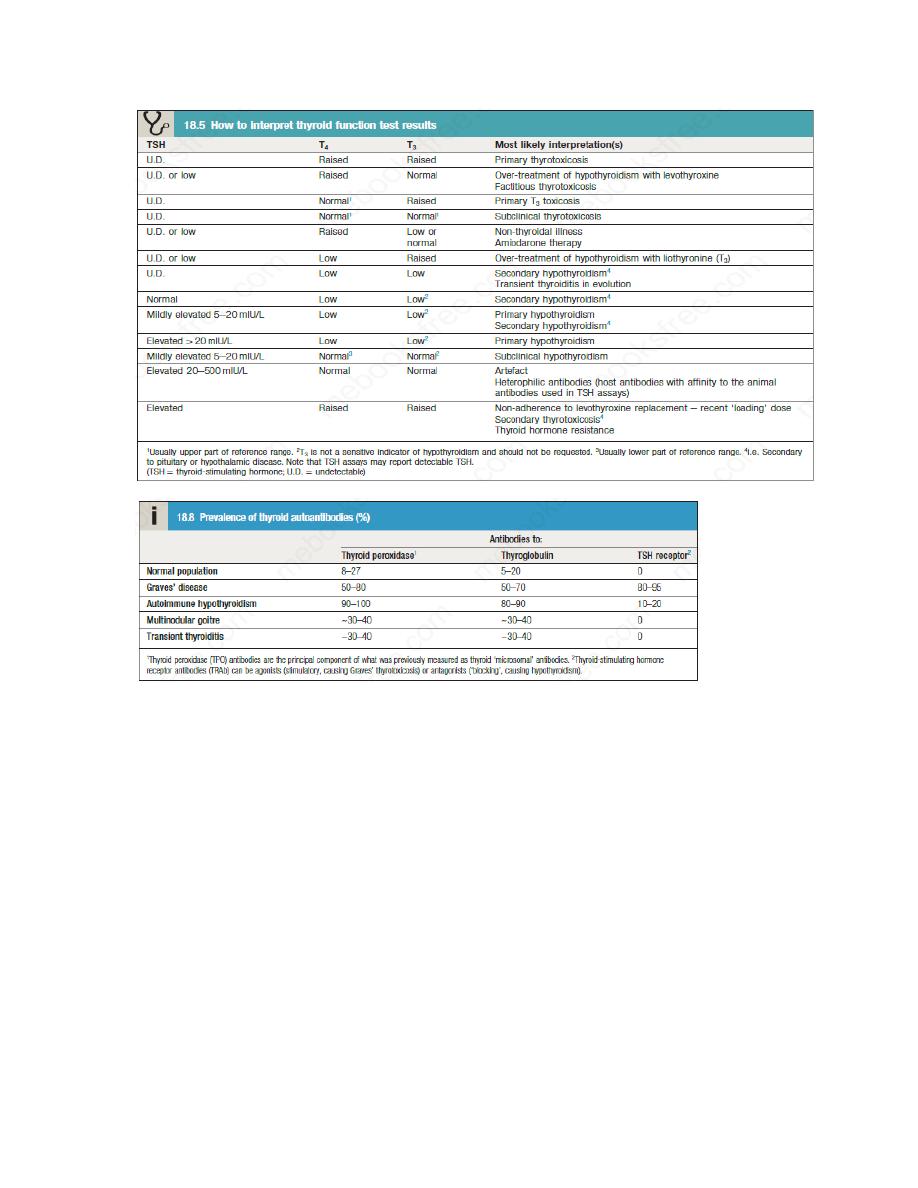

TSH is usually regarded as the most useful investigation of thyroid function. However,

interpretation of TSH values without considering thyroid hormone levels may be misleading in

patients with pituitary disease; for example, TSH is inappropriately low or ‘normal’ in secondary

hypothyroidism.

Other modalities commonly employed in the investigation of thyroid disease include

measurement of antibodies against the TSH receptor or other thyroid antigens, radioisotope

imaging, fine needle aspiration biopsy and ultrasound.

Presenting problems in thyroid disease

The most common presentations are hyperthyroidism(thyrotoxicosis), hypothyroidism and

enlargement of the thyroid(goitre or thyroid nodule). Widespread availability of thyroid function

tests has led to the increasingly frequent identification of patients with abnormal results who

either are asymptomatic or have non-specific complaints such as tiredness and weight gain.

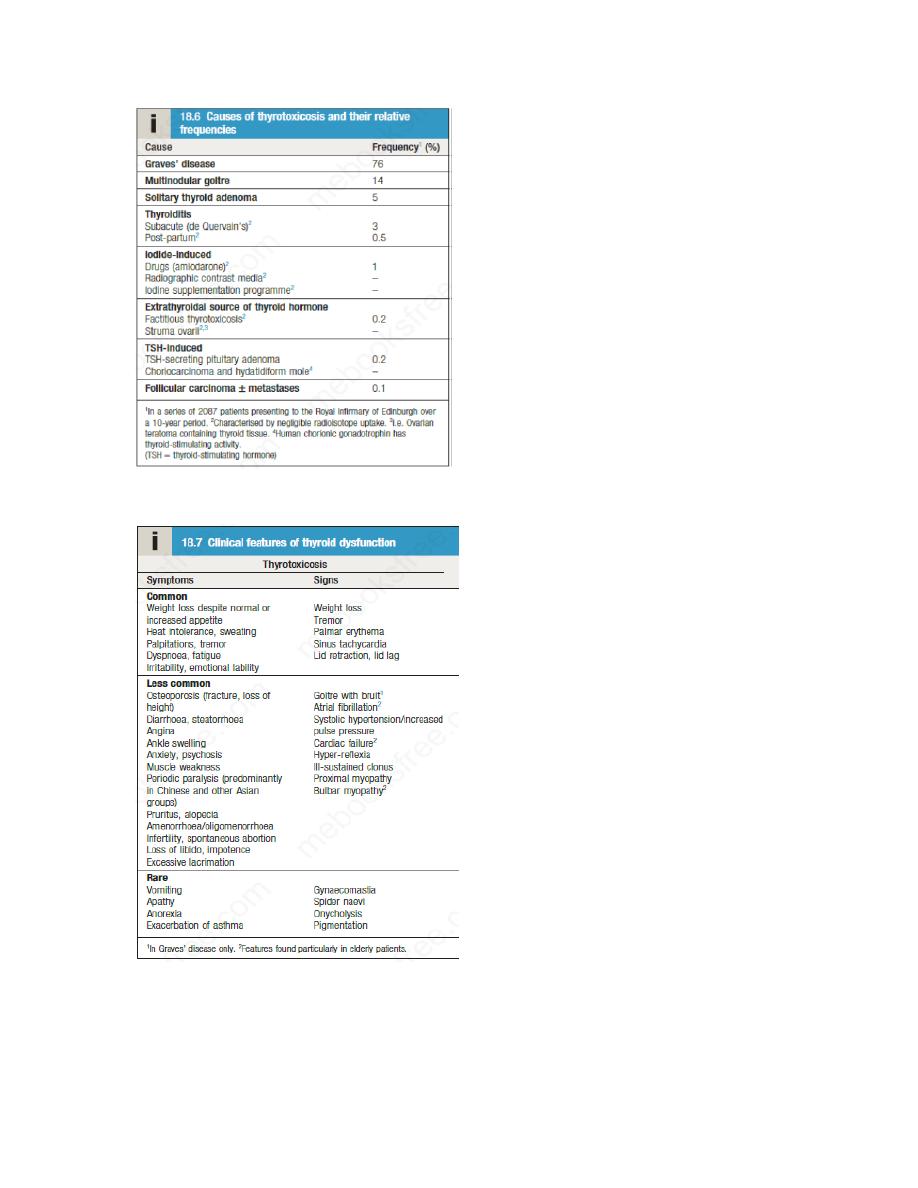

Thyrotoxicosis

Thyrotoxicosis describes a constellation of clinical features arising from elevated circulating

levels of thyroid hormone. The most common causes are Graves’ disease, multinodular goitre

and autonomously functioning thyroid nodules (toxic adenoma) . Thyroiditis is more common in

parts of the world where relevant viral infections occur, such as North America.

Clinical assessment

The most common symptoms are weight loss with a normal or increased appetite, heat

intolerance, palpitations, tremor and irritability. Tachycardia, palmar erythema and lid lag are

common signs. Not all patients have a palpable goitre, but experienced clinicians can

discriminate the diffuse soft goitre of Graves’ disease from the irregular enlargement of a

multinodular goitre. All causes of thyrotoxicosis can cause lid retraction and lid lag, due to

potentiation of sympathetic innervation of the levator palpebrae muscles, but only Graves’

disease causes other features of ophthalmopathy, including periorbital oedema, conjunctival

irritation, exophthalmos and diplopia. Pretibial myxedema and the rare thyroid acropachy (a

periosteal hypertrophy, indistinguishable from finger clubbing) are also specific to

Graves’disease.

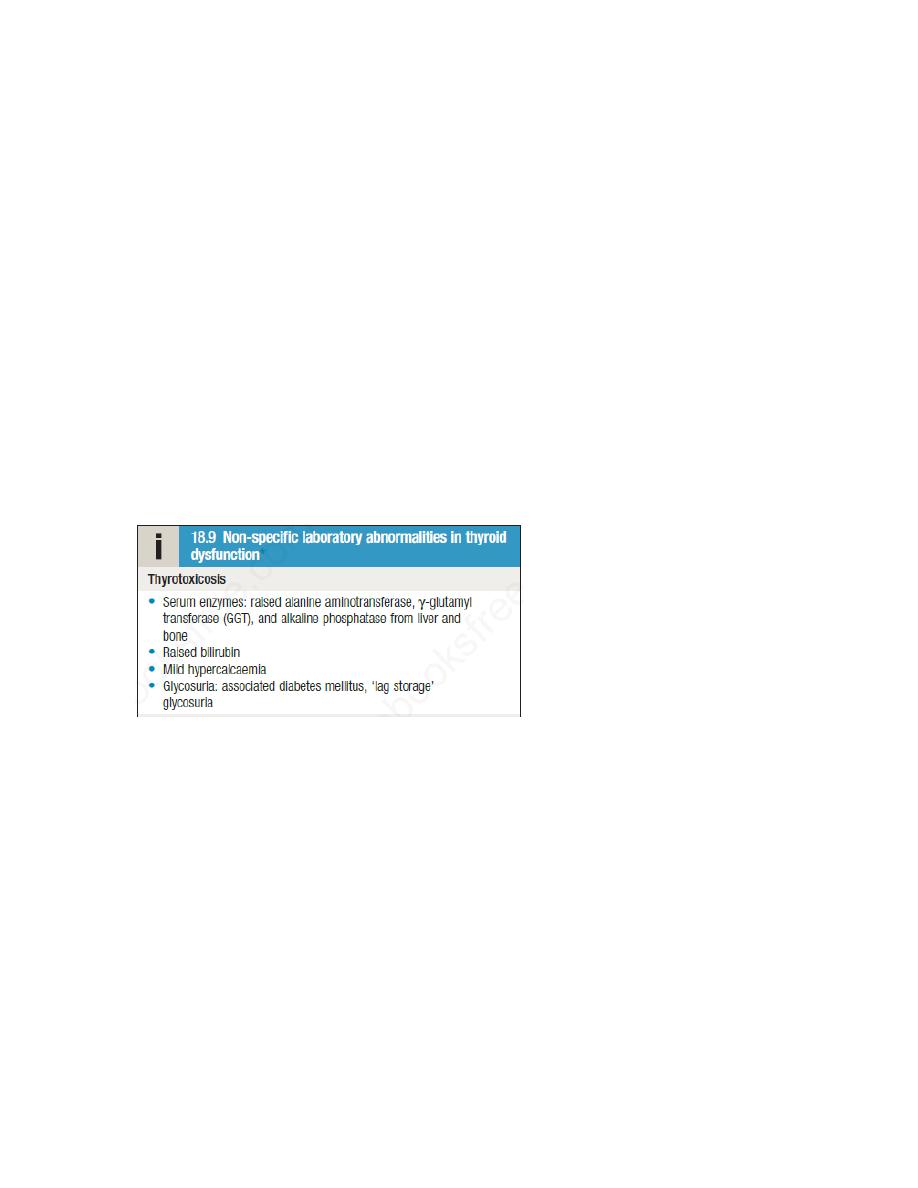

Investigations

The first-line investigations are serum T3, T4 and TSH. If abnormal values are found, the tests

should be repeated and the abnormality confirmed in view of the likely need for prolonged

medical treatment or destructive therapy. In most patients, serum T3 and T4 are both elevated,

but T4 is in the upper part of the reference range and T3 is raised (T3 toxicosis) in about 5%.

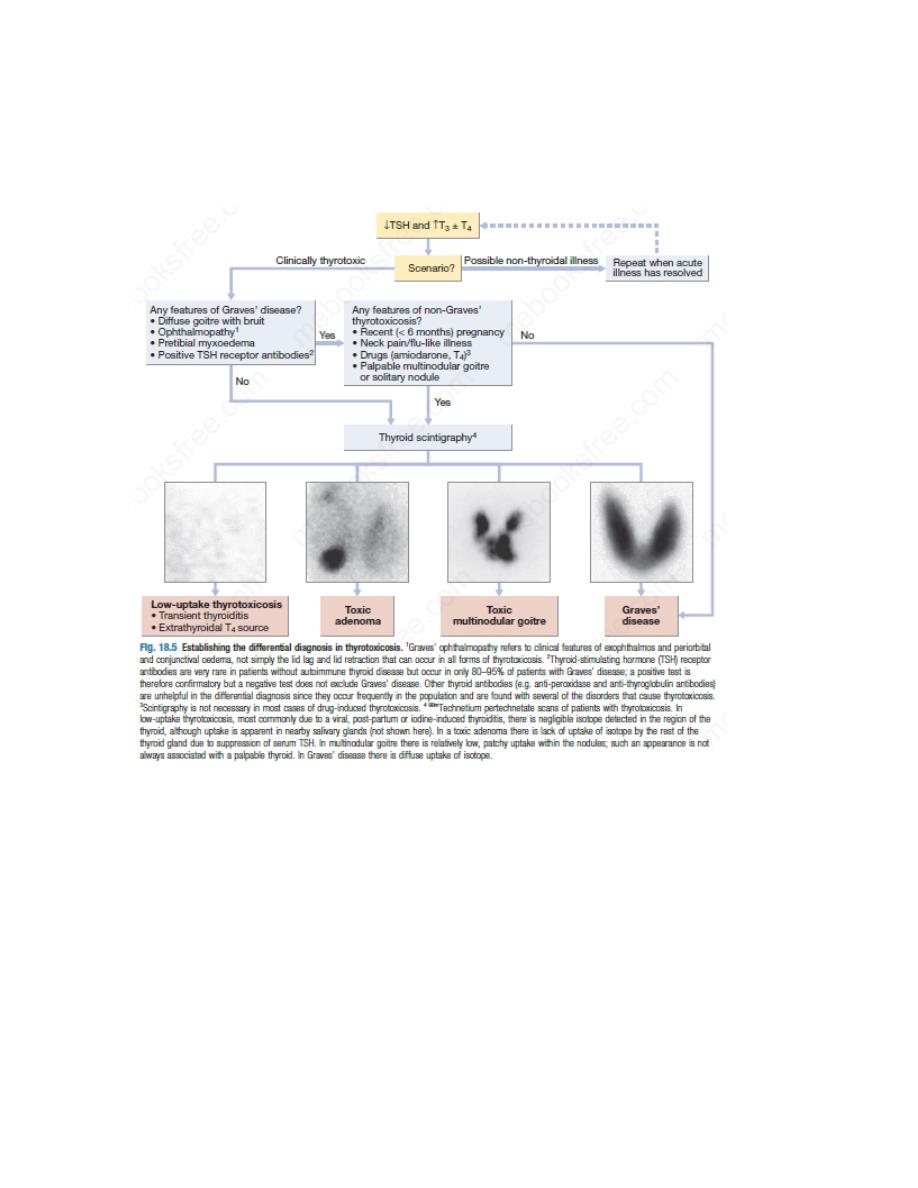

Serum TSH is undetectable in primary thyrotoxicosis, but values can be raised in the very rare

syndrome of secondary thyrotoxicosis caused by a TSH-producing pituitary adenoma. When

biochemical thyrotoxicosis has been confirmed, further investigations should be undertaken to

determine the underlying cause, including measurement of TSH receptor antibodies (TRAb,

elevated in Graves’ disease) and radioisotope scanning.

Other investigation like an electrocardiogram (ECG) may demonstrate sinus tachycardia or atrial

fibrillation.

Radio-iodine uptake tests measure the proportion of isotope that is trapped in the whole gland

but have been largely superseded by 99mtechnetium scintigraphy scans, which also indicate

trapping, are quicker to perform with a lower dose of radioactivity, and provide a higher-

resolution image. In low-uptake thyrotoxicosis, the cause is usually a transient thyroiditis.

Occasionally, patients induce ‘factitious thyrotoxicosis’ by consuming excessive amounts of a

thyroid hormone preparation, most often levothyroxine. The exogenous levothyroxine

suppresses pituitary TSH secretion and hence iodine uptake, serum thyroglobulin and release of

endogenous thyroid hormones. The T4:T3 ratio (typically 30 : 1 in conventional thyrotoxicosis) is

increased to above 70 : 1 because circulating T3 in factitious thyrotoxicosis is derived exclusively

from the peripheral monodeiodination of T4 and not from thyroid secretion. The combination of

negligible iodine uptake, high T4:T3 ratio and a low or undetectable thyroglobulin is diagnostic.

Management

Definitive treatment of thyrotoxicosis depends on the underlying cause and may include

antithyroid drugs, radioactive iodine or surgery. A non-selective β-adrenoceptor antagonist (β-

blocker), such as propranolol (160 mg daily) or nadolol (40–80 mg daily), will alleviate but not

abolish symptoms in most patients within 24–48 hours. Beta-blockers should not be used for

long-term treatment of thyrotoxicosis but are extremely useful in the short term, while patients

are awaiting hospital consultation or following 131I therapy. Verapamil may be used as an

alternative to β-blockers, e.g. in patients with asthma, but usually is only effective in improving

tachycardia and has little effect on the other systemic manifestations of thyrotoxicosis.

Atrial fibrillation in thyrotoxicosis

Atrial fibrillation occurs in about 10% of patients with thyrotoxicosis. The incidence increases

with age, so that almost half of all males with thyrotoxicosis over the age of 60 are affected.

Moreover, subclinical thyrotoxicosis is a risk factor for atrial fibrillation.

Characteristically, the ventricular rate is little influenced by digoxin but responds to the addition

of a β-blocker. Thromboembolic vascular complications are particularly common in thyrotoxic

atrial fibrillation so that anticoagulation is required, unless contraindicated. Once thyroid

hormone and TSH concentrations have been returned to normal, atrial fibrillation will

spontaneously revert to sinus rhythm in about 50% of patients but cardioversion may be

required in the remainder.

Thyrotoxic crisis (‘thyroid storm’)

This is a rare but life-threatening complication of thyrotoxicosis. The most prominent signs are

fever, agitation, delirium, tachycardia or atrial fibrillation and, in the older patient, cardiac

failure. The thyrotoxic crisis is a medical emergency and has a mortality of 10% despite early

recognition and treatment. It is most commonly precipitated by infection in a patient with

previously unrecognised or inadequately treated thyrotoxicosis. It may also develop in known

thyrotoxicosis shortly after thyroidectomy in an ill-prepared patient or within a few days of 131I

therapy, when acute radiation damage may lead to a transient rise in serum thyroid hormone

levels.

Patients should be rehydrated and given propranolol, either orally (80 mg 4 times daily) or

intravenously (1–5 mg 4 times daily). Sodium ipodate (500 mg per day orally) will restore serum

T3 levels to normal in 48–72 hours. This is a radiographic contrast medium that not only inhibits

the release of thyroid hormones but also reduces the conversion of T4 to T3, and is therefore

more effective than potassium iodide or Lugol’s solution. Dexamethasone (2 mg 4 times daily)

and amiodarone have similar effects. Oral carbimazole 40–60 mg daily should be given to inhibit

the synthesis of new thyroid hormone.If the patient is unconscious or uncooperative,

carbimazole can be administered rectally with good effect but no preparation is available for

parenteral use. After 10–14 days the patient can usually be maintained on carbimazole alone.