KEY LEARNING POINTS of the previous lecture:

• The pelvic inlet is wider in the transverse than in the AP diameter.

• The pelvic outlet is wider in the AP than in the transverse diameter.

• The ischial spines are located in the midpelvis and denote station zero.

• The fetal head enters the pelvis in a transverse position, rotates in the midpelvis and

delivers in an AP position.

• Pelvic dimensions may increase during labour due to pelvic ligament laxity.

• The shape of the pelvis and pelvic floor muscles aid flexion and rotation of the fetal head.

• The sutures and fontanelles are used to assess the position and attitude of the fetal head.

• Moulding of the skull bones during labour reduces the measurements of the fetal head.

• A fetus in a flexed OA (occipito-anterior) position with a gynaecoid pelvis is most

favorable for vaginal birth.

• Perineal tissues offer resistance to delivery especially in a nulliparous woman.

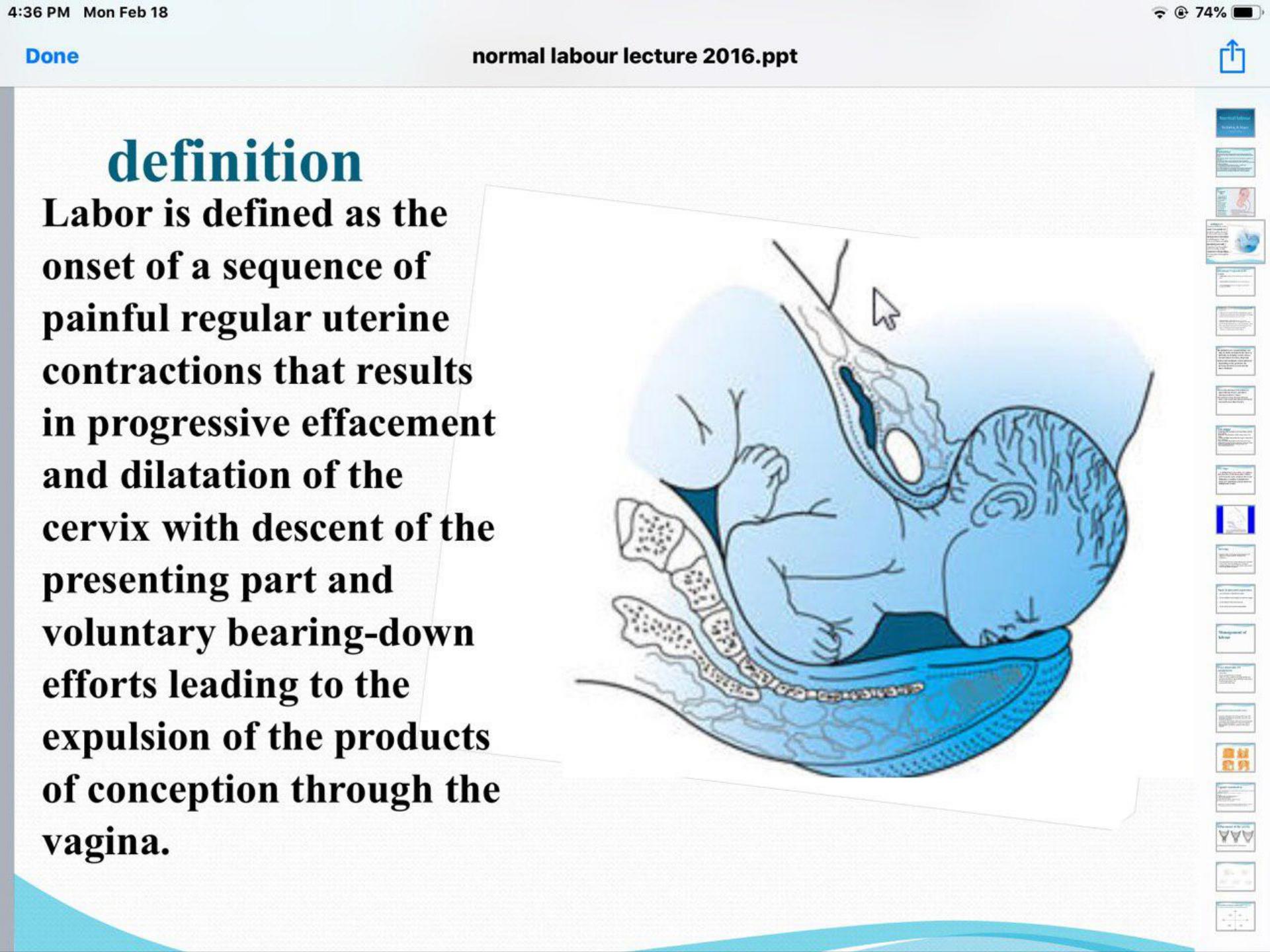

Physiology of labour

The mechanisms underlying human parturition are not fully understood and differ from other

animal models that have been studied. In particular, the process that initiates labour is poorly

understood. There are a number of important elements.

The cervix, which is initially long, firm, and closed, with a protective mucus plug, must soften,

shorten, thin out (effacement) and dilate for labour to progress. The uterus must change from a

state of relaxation to an active state of regular, strong, frequent contractions to facilitate transit

of the fetus through the birth canal. Each contraction must be followed by a resting phase in

order to maintain placental blood flow and adequate perfusion of the fetus. The pressure of the

presenting part on the pelvic floor muscles as the fetus descends from the midpelvis to the

pelvic outlet produces a maternal urge to push, enhanced further by stretching of the perineum.

The onset of labour occurs when the factors that inhibit contractions and maintain a closed

cervix diminish and are overtaken by the actions of factors that do the opposite. Both mother

and fetus appear to contribute to this process.

The uterus

Myometrial cells of the uterus contain filaments of actin and myosin, which interact and bring

about contractions in response to an increase in intracellular calcium. Prostaglandins and

oxytocin increase intracellular free calcium ions, whereas beta-adrenergic compounds and

calcium-channel blockers do the opposite. Separation of the actin and myosin filaments brings

about relaxation of the myocyte; however, unlike any other muscle cell of the body, this actin–

myosin interaction occurs along the full length of the filaments so that a degree of shortening

occurs with each successive interaction. This progressive shortening of the uterine smooth

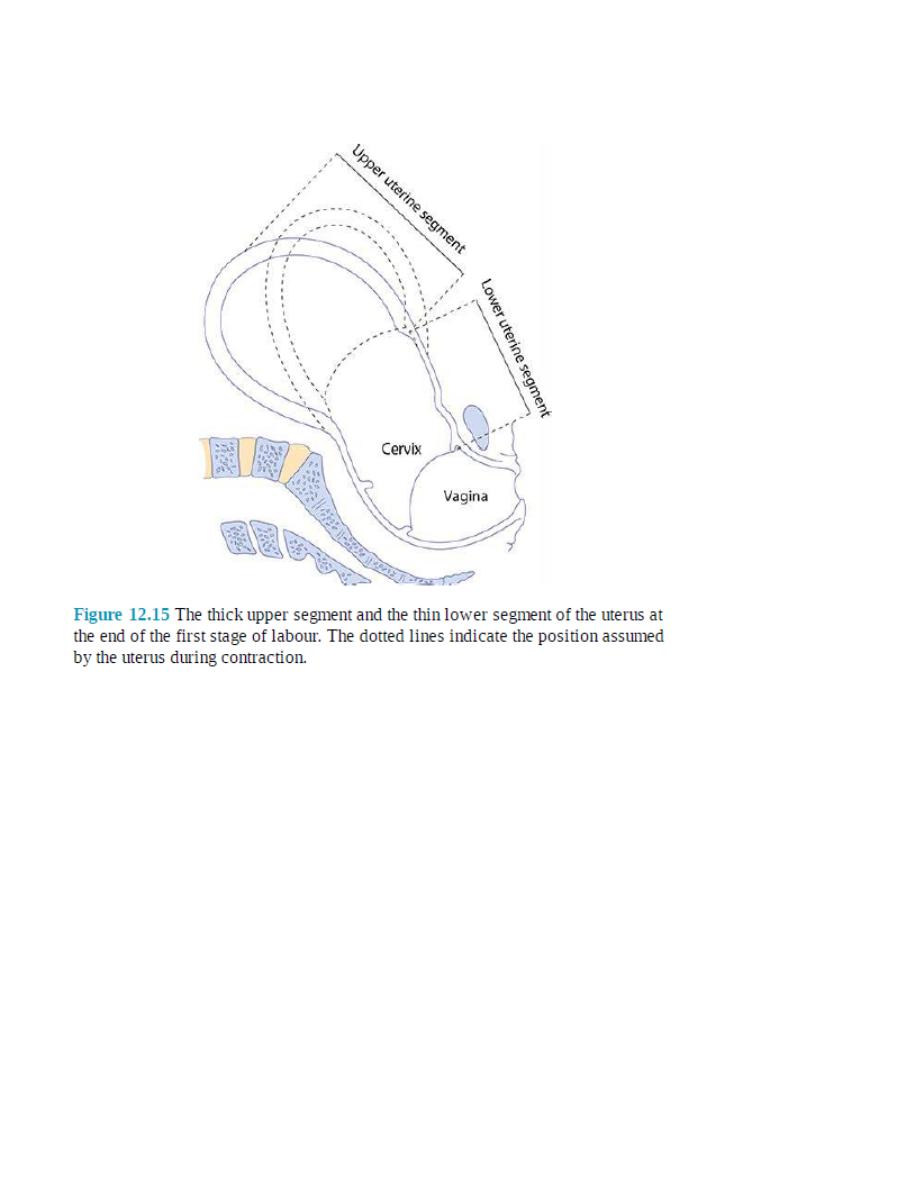

muscle cells is called retraction and occurs in the cells of the upper part of the uterus. The result

of this retraction process is the development of the thicker, actively contracting ‘upper

segment’. At the same time, the lower segment of the uterus becomes thinner and more

stretched. Eventually, this results in the cervix being ‘taken up’ (effacement) into the lower

segment of the uterus so forming a continuum with the lower uterine segment (Figure 12.15).

The cervix effaces and then dilates, and the fetus descends in response to this directional force.

It is essential that the myocytes of the uterus contract in a coordinated way.

Individual myometrial cells are laid down in a mesh of collagen. There is cell-tocell

communication by means of gap junctions, which facilitate the passage of various products of

metabolism and electrical current between cells. These gap junctions are absent for most of the

pregnancy but appear in significant numbers at term. Gap junctions increase in size and number

with the progress of labour and allow greater coordination of myocyte activity. Prostaglandins

stimulate their formation, while beta-adrenergic compounds are thought to do the opposite.

A uterine pacemaker from which contractions originate probably exists but has not been

demonstrated histologically.

Uterine contractions are involuntary in nature and there is relatively little extrauterine neuronal

control. The frequency of contractions may vary during labour and with parity. Throughout the

majority of labour, they occur at intervals of 2–4 minutes and are described in terms of the

frequency within a 10-minute period (i.e. 2 in 10 increasing to 4–5 in 10 in advanced labour).

Their duration also varies during labour, from 30 to 60 seconds or occasionally longer. The

frequency of contractions can be recorded on a cardiotocograph (CTG) using a pressure

transducer (tocodynamometer) positioned on the abdomen at the fundus of the uterus. The

intensity or amplitude of the intrauterine pressure generated with each contraction averages

between 30 and 60 mmHg.

The cervix

The cervix contains myocytes and fibroblasts separated by a ‘ground substance’ made up of

extracellular matrix molecules. Interactions between collagen, fibronectin and dermatan

sulphate (a proteoglycan) during the earlier stages of pregnancy keep the cervix firm and closed.

Contractions at this point do not bring about effacement or dilatation. Under the influence of

prostaglandins, and other humoral mediators, there is an increase in proteolytic activity and a

reduction in collagen and elastin. Interleukins bring about a proinflammatory change with a

significant invasion by neutrophils. Dermatan sulphate is replaced by the more hydrophilic

hyaluronic acid, which results in an increase in water content of the cervix. This causes cervical

softening or ‘ripening’, so that contractions, when they begin, can bring about the processes of

effacement and dilatation.

Hormonal factors

Progesterone maintains uterine relaxation by suppressing prostaglandin production, inhibiting

communication between myometrial cells and preventing oxytocin release. Oestrogen opposes

the action of progesterone. Prior to labour, there is a reduction in progesterone receptors and an

increase in the concentration of oestrogen relative to progesterone. Prostaglandin synthesis by

the chorion and the decidua is enhanced, leading to an increase in calcium influx into the

myometrial cells. This change in the hormonal milieu also increases gap junction formation

between individual myometrial cells, creating a functional syncytium, which is necessary for

coordinated uterine activity. The production of corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH) by the

placenta increases in concentration towards term and potentiates the action of prostaglandins

and oxytocin on myometrial contractility. The fetal pituitary secretes oxytocin and the fetal

adrenal gland produces cortisol, which stimulates the conversion of progesterone to oestrogen.

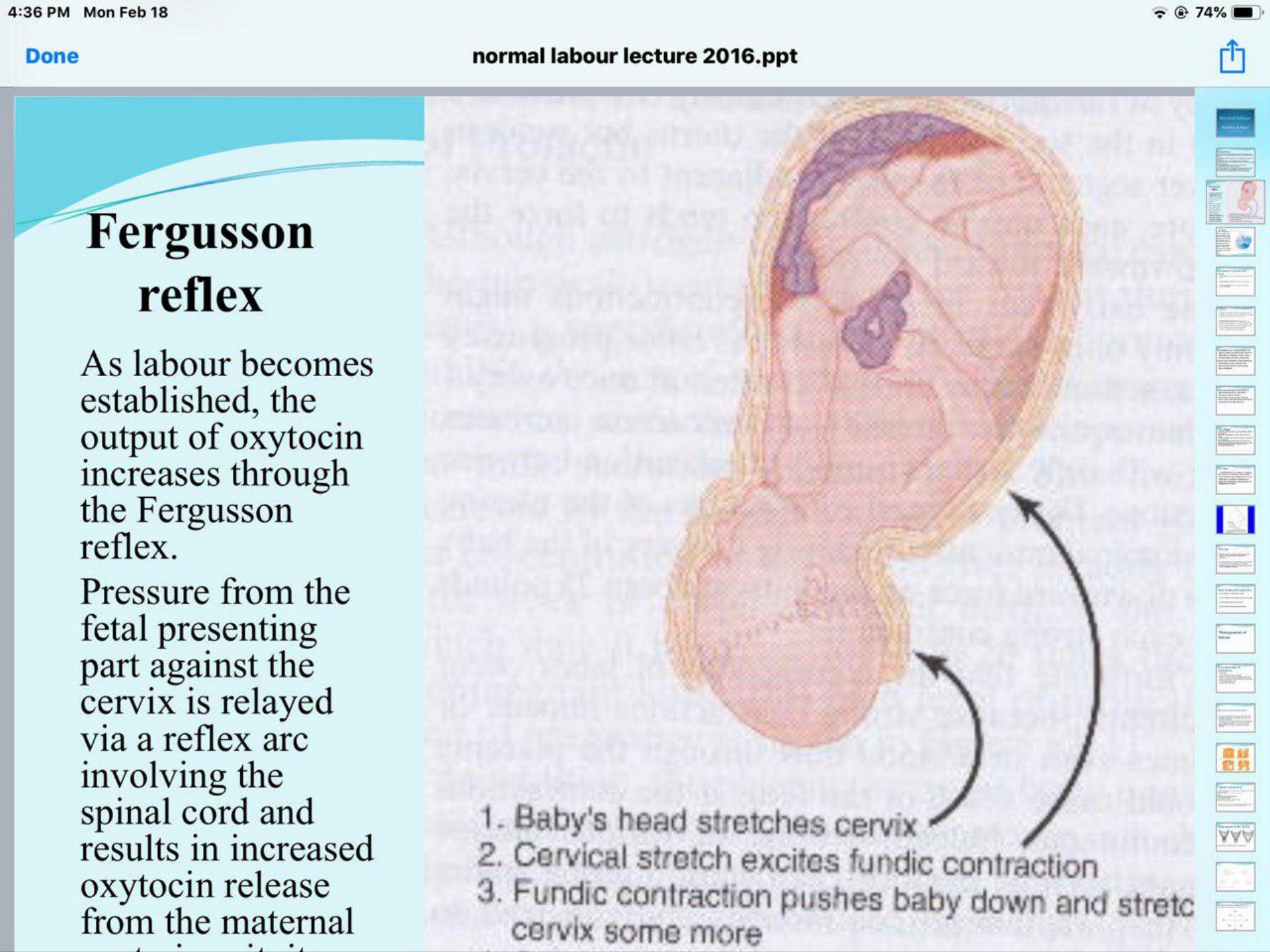

It is unclear which of these hormonal changes actually initiates labour. As labour becomes

established, the output of oxytocin increases through the ‘Fergusson reflex’. Pressure from the

fetal presenting part against the cervix is relayed via a reflex arc involving the spinal cord and

results in increased oxytocin release from the maternal posterior pituitary.

Diagnosis of labour

The onset of labour can be defined as the presence of strong regular painful contractions

resulting in progressive cervical change. Therefore, a diagnosis of labour strictly speaking

requires more than one vaginal examination after an interval and is made in retrospect. In

practice, the diagnosis is suspected when a woman presents with contraction-like pains, and is

confirmed when the midwife performs a vaginal examination that reveals effacement and

dilatation of the cervix. Loss of a ‘show’ (a blood-stained plug of mucus passed from the

cervix) or spontaneous rupture of the membranes (SROM) does not define the onset of labour,

although these events may occur around the same time. Labour can be well established before

either of these events occurs, and both may precede labour by many days. Although much is

understood about the physiology of labour in humans, the initiating process is still unclear. It is

certainly true, however, that the uterus and cervix undergo a number of changes in preparation

for labour, which start a number of weeks before its onset.

Stages of labour

Labour can be divided into three stages. The definitions of these stages rely predominantly on

anatomical criteria, and in real terms the moment of transition from first to second stage may

not be apparent. The important events when labour is normal are the diagnosis of labour and the

maternal urge to push, which usually corresponds with full dilatation of the cervix and the

baby’s head resting on the perineum. Defining the three stages of labour becomes more relevant

if labour is not progressing normally. The average duration of a first labour is 8 hours, and that

of a subsequent labour 5 hours. First labour rarely lasts more than 18 hours, and second and

subsequent labours not usually more than 12 hours.

First stage

This describes the time from the diagnosis of labour to full dilatation of the cervix (10 cm). The

first stage of labour can be divided into two phases. The ‘latent phase’ is the time between the

onset of regular painful contractions and 3–4 cm cervical dilatation. During this time, the cervix

becomes ‘fully effaced’.

Effacement is a process by which the cervix shortens in length as it becomes incorporated into

the lower segment of the uterus. The process of effacement may begin during the weeks

preceding the onset of labour, but will be complete by the end of the latent phase. Effacement

and dilatation should be thought of as consecutive events in the nulliparous woman, but they

may occur simultaneously in the multiparous woman. Dilatation is expressed in centimetres

from 0 to 10 cm.

The duration of the latent phase is variable, and time limits are arbitrary.

However, it usually lasts between 3 and 8 hours, being shorter in multiparous women.

The second phase of the first stage of labour is called the ‘active phase’ and describes the time

between the end of the latent phase (3–4 cm dilatation) and full cervical dilatation (10 cm). It is

also variable in length, usually lasting between 2 and 6 hours, shorter in multiparous women.

Cervical dilatation during the active phase occurs typically at 1 cm/hour or more in a normal

labour (again, an arbitrary value), but is only considered abnormal if it occurs at less than 1 cm

in 2 hours.

Second stage

This describes the time from full dilatation of the cervix to delivery of the fetus or fetuses. The

second stage of labour may also be subdivided into two phases. The ‘passive phase’ describes

the time between full dilatation and the onset of involuntary expulsive contractions. There is no

maternal urge to push and the fetal head is still relatively high in the pelvis. The second phase is

called the ‘active second stage’. There is a maternal urge to push because the fetal head is low

(often visible), causing a reflex need to ‘bear down’. In a normal labour, the second stage is

often diagnosed at this late point because the maternal urge to push prompts the midwife to

perform a vaginal examination. If a woman never reaches a point of involuntary pushing, the

active second stage is said to begin when she starts making voluntary pushing efforts directed

by her midwife. Conventionally, a normal active second stage should last no longer than 2

hours in a nulliparous woman and 1 hour in women who delivered vaginally before. Again,

these definitions are fairly arbitrary, but there is evidence that a second stage of labour lasting

more than 3 hours is associated with increased maternal and fetal morbidity. Use of epidural

anaesthesia will influence the length and management of the second stage of labour. A passive

second stage of 1 or 2 hours is usually recommended to allow the head to rotate and descend

prior to active pushing.

Third stage

This is the time from delivery of the fetus or fetuses until complete delivery of the placenta(e)

and membranes. The placenta is usually delivered within a few minutes of the birth of the baby.

A third stage lasting more than 30 minutes is defined as abnormal, unless the woman has opted

for ‘physiological management’ in which case it is reasonable to extend this definition to 60

minutes.

The duration of labour

There is no ideal length of labour for all women but morbidity increases when labour is too fast

(precipitous) or two slow (prolonged). From a psychological perspective, the morale of most

women starts to deteriorate after 6 hours in labour, and after 12 hours the rate of deterioration

accelerates. There is a greater incidence of fetal hypoxia and need for operative delivery

associated with longer labours. It is difficult to define prolonged labour, but it would be

reasonable to suggest that labour lasting longer than 12 hours in nulliparous women and 8 hours

in multiparous women should be regarded as prolonged. Precipitous labour is defined as

expulsion of the fetus within less than 3 hours of the onset of regular contractions.