1

Herpesviruses

The herpesvirus family contains several of the most important human viral pathogens.

Clinically, the herpesviruses exhibit a spectrum of diseases.

Some have a wide host-cell range, and others have a narrow host-cell range.

The outstanding property of herpesviruses is their ability to establish lifelong persistent

infections in their hosts and to undergo periodic reactivation.

Their frequent reactivation in immunosuppressed patients causes serious health

complications.

Curiously, the reactivated infection may be clinically quite different from the disease caused

by the primary infection.

Herpesviruses possess a large number of genes, some of which have proved to be susceptible

to antiviral chemotherapy.

The herpesviruses that commonly infect humans include: herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2

(HSV-1, HSV-2), varicellazoster virus, cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV),

herpesviruses 6 and 7, and herpesvirus 8 (Kaposisarcoma-associated herpesvirus [KSHV]).

Herpes B virus of monkeys can also infect humans.

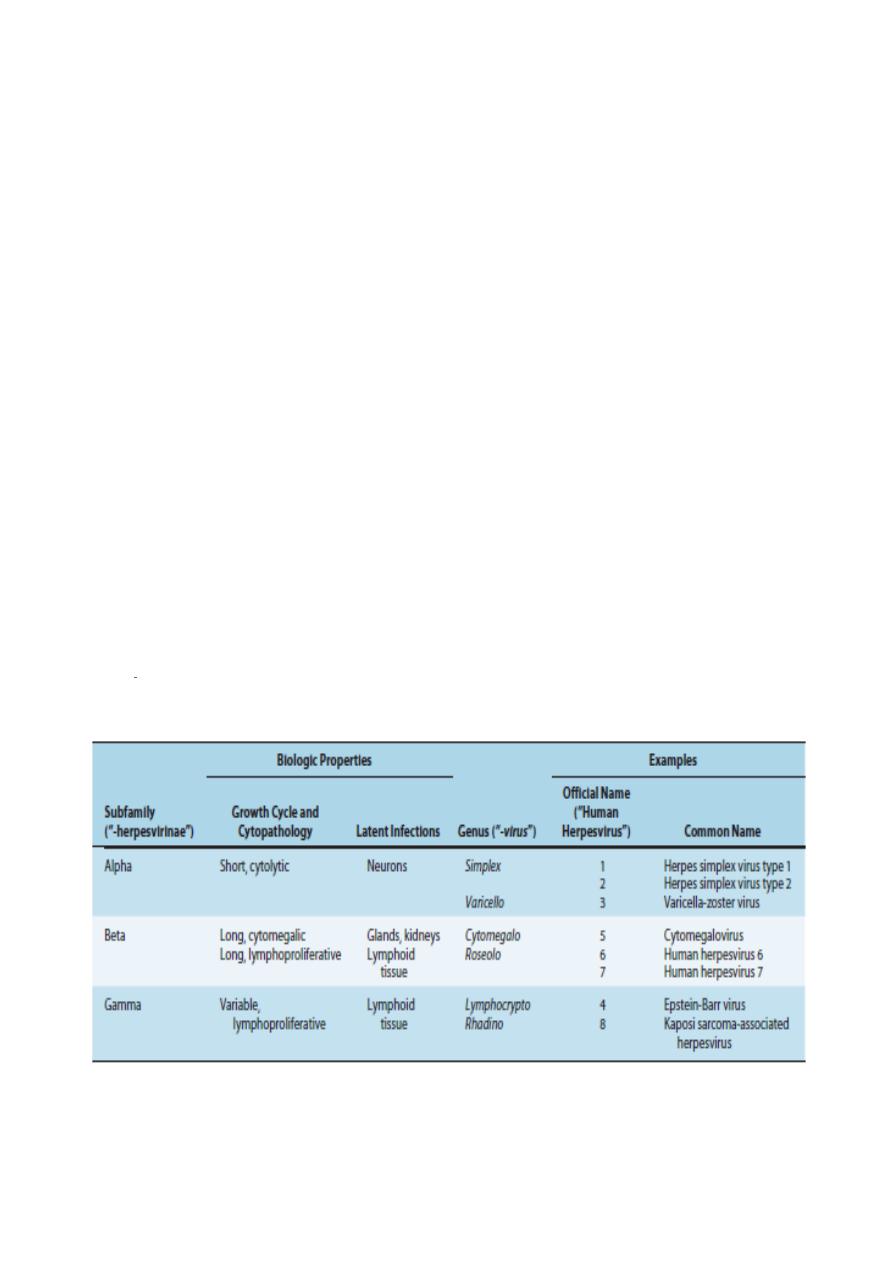

Table 1. Important Properties of Herpesviruses

Virion: Spherical, 150–200 nm in diameter (icosahedral)

genome : Double-stranded DNA, linear, 125–240 kbp, reiterated sequences

Proteins: More than 35 proteins in virion

envelope: Contains viral glycoproteins, Fc receptors

Replication: Nucleus, bud from nuclear membrane

Outstanding characteristics:

Encode many enzymes

Establish latent infections

Persist indefinitely in infected hosts

Frequently reactivated in immunosuppressed hosts

Some cause cancer

Table 2. Classification of Human Herpesviruses.

Many herpesviruses infect animals, the most notable being B virus (herpesvirus simiae) in the

Simplexvirus

2

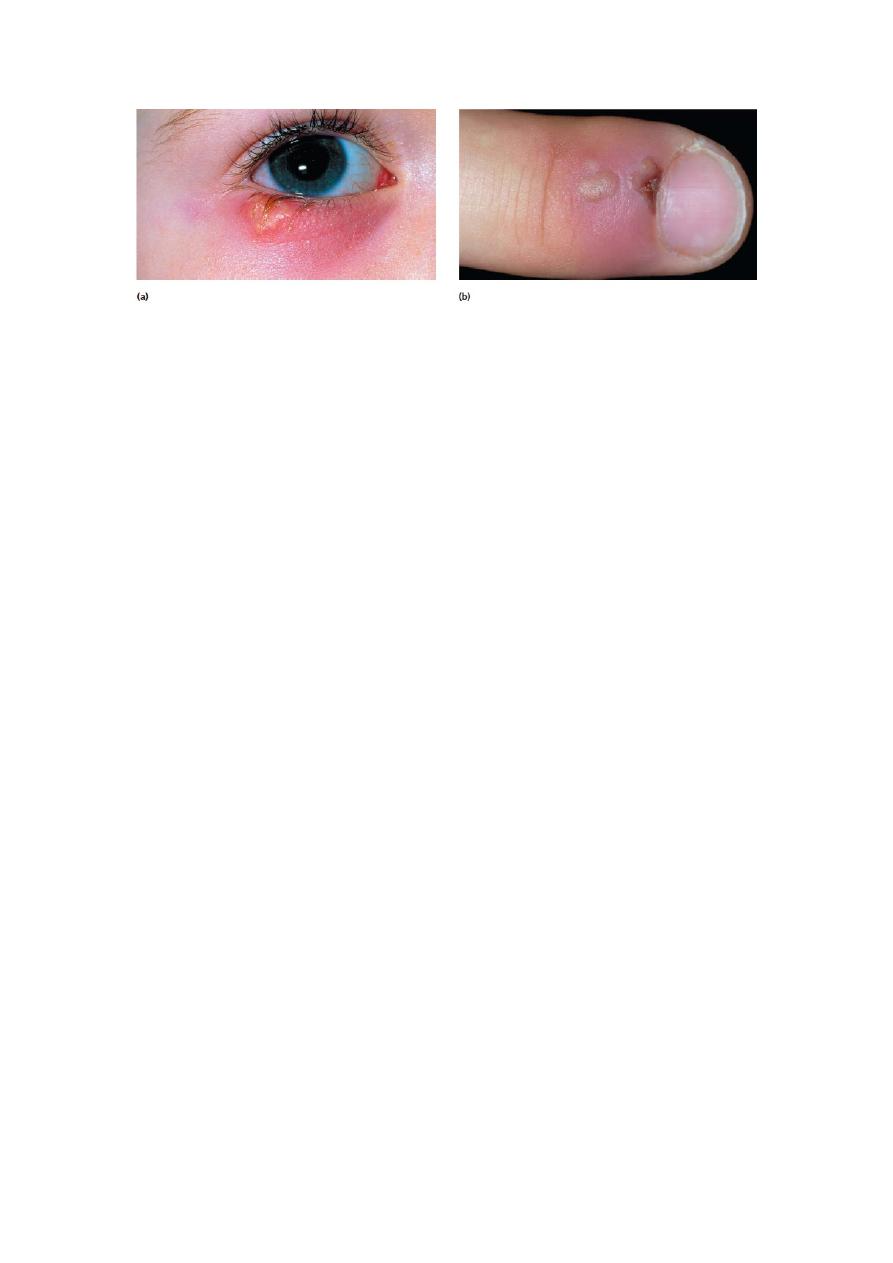

Herpes lesions of the eyes and skin.

(a) Ophthalmic or ocular herpes results from reactivation of latent viruses in the trigeminal

ganglion.

(b) A whitlow on a health provider’s finger, resulting from the entry of herpesvirus through a

break in the skin of the finger.

Overview of Herpesvirus Diseases

A wide variety of diseases are associated with infection by herpesviruses.

Primary infection and reactivated disease by a given virus may involve different cell types

and present different clinical pictures.

HSV-1 and HSV-2 infect epithelial cells and establish latent infections in neurons.

Type 1 is classically associated with oropharyngeal lesions and causes recurrent attacks of

―fever blisters.‖

Type 2 primarily infects the genital mucosa and is mainly responsible for genital herpes.

Both viruses also cause neurologic disease. HSV-1 is the leading cause of sporadic

encephalitis in the United States.

Both types 1 and 2 can cause neonatal infections that are often severe.

Varicella-zoster virus causes chickenpox (varicella) on primary infection and establishes

latent infection in neurons.

Upon reactivation, the virus causes zoster (shingles).

Adults who are infected for the first time with varicella-zoster virus are apt to develop serious

viral pneumonia.

CMV replicates in epithelial cells of the respiratory tract, salivary glands, and kidneys and

persists in lymphocytes.

It causes an infectious mononucleosis (heterophil-negative).

In newborns, cytomegalic inclusion disease may occur.

CMV is an important cause of congenital defects and mental retardation.

HHV-6 infects T lymphocytes. It is typically acquired in early infancy and causes exanthem

subitum (roseola infantum).

HHV-7, also a T-lymphotropic virus, has not yet been linked to any specific disease.

EBV replicates in epithelial cells of the oropharynx and parotid gland and establishes latent

infections in lymphocytes.

It causes infectious mononucleosis and is the cause of human lymphoproliferative disorders,

especially in immunocompromised patients. HHV-8 appears to be associated with the

development of Kaposi sarcoma, a vascular tumor that is common in patients with AIDS.

Herpes B virus of macaque monkeys can infect humans.

Such infections are rare, but those that occur usually result in severe neurologic disease and

are frequently fatal.

Human herpesviruses are frequently reactivated in immunosuppressed patients (eg, transplant

recipients, cancer patients) and may cause severe disease, such as pneumonia or lymphomas.

Herpesviruses have been linked with malignant diseases in humans and lower animals:

3

EBV with Burkitt lymphoma of African children, with nasopharyngeal carcinoma, and with

other lymphomas; KSHV with Kaposi sarcoma; Marek disease virus with a lymphoma of

chickens; and a number of primate herpesviruses with reticulum cell sarcomas and

lymphomas in monkeys.

HERPESVIRUS INFECTIONS IN HUMANS

Herpes Simplex Viruses

There are two distinct HSV, types 1 and 2 (HSV-1 and HSV-2).

Their genomes are similar in organization and exhibit substantial sequence homology.

The two viruses cross-react serologically, but some unique proteins exist for each type.

They differ in their mode of transmission.

Whereas HSV-1 is spread by contact, usually involving infected saliva, HSV-2 is transmitted

sexually or from a maternal genital infection to a newborn.

The HSV growth cycle proceeds rapidly, requiring 8–16 hours for completion.

At least eight viral glycoproteins are among the viral late gene products.

Glycoprotein G is type specific and allows for antigenic discrimination between HSV-1 (gG-

1) and HSV-2 (gG-2).

Clinical Findings

HSV-1 and HSV-2 may cause many clinical entities, and the infections may be primary or

recurrent.

Primary infections occur in persons without antibodies and in most individuals are clinically

inapparent but result in antibody production and establishment of latent infections in sensory

ganglia. Recurrent lesions are common.

A.

Oropharyngeal Disease

Primary HSV-1 infections are usually asymptomatic.

Symptomatic disease occurs most frequently in small children (1–5 years of age) and involves

the buccal and gingival mucosa of the mouth .

The incubation period is short (~3–5 days, with a range of 2–12 days), and clinical illness

lasts 2–3 weeks.

Symptoms include fever, sore throat, vesicular and ulcerative lesions, gingivostomatitis, and

malaise.

Gingivitis (swollen, tender gums) is the most striking and common lesion.

Primary infections in adults commonly cause pharyngitis and tonsillitis.

Localized lymphadenopathy may occur.

Recurrent disease is characterized by a cluster of vesicles most commonly localized at the

border of the lip.

Intense pain occurs at the outset but fades over 4–5 days.

The frequency of recurrences varies widely among individuals.

Many recurrences of oral shedding are asymptomatic and of short duration (24 hours).

B.

Keratoconjunctivitis

HSV-1 infections may occur in the eye, producing severe keratoconjunctivitis.

Recurrent lesions of the eye are common and appear as dendritic keratitis or corneal ulcers or

as vesicles on the eyelids.

With recurrent keratitis, there may be progressive involvement of the corneal stroma, with

permanent opacification and blindness.

HSV-1 infections are second only to trauma as a cause of corneal blindness in the United

States.

C.

Genital Herpes

Genital disease is usually caused by HSV-2, although HSV-1 can also cause clinical episodes

of genital herpes.

Primary genital herpes infections can be severe, with illness lasting about 3 weeks.

4

The lesions are very painful and may be associated with fever, malaise, dysuria, and inguinal

lymphadenopathy.

Complications include extragenital lesions (~20% of cases) and aseptic meningitis (~10% of

cases).

Viral excretion persists for about 3 weeks.

Because of the antigenic cross-reactivity between HSV-1 and HSV-2, preexisting immunity

provides some protection against heterotypic infection.

An initial HSV-2 infection in a person already immune to HSV-1 tends to be less severe.

Recurrences of genital herpetic infections are common and tend to be mild. A limited number

of vesicles appear and heal in about 10 days. Virus is shed for only a few days.

D.

Skin Infections

Intact skin is resistant to HSV, so cutaneous HSV infections are uncommon in healthy

persons.

Localized lesions caused by HSV-1 or HSV-2 may occur in abrasions that become

contaminated with the virus (traumatic herpes). These lesions are seen on the fingers of

dentists and hospital personnel (herpetic whitlow) and on the bodies of wrestlers (herpes

gladiatorum or mat herpes).

Cutaneous infections are often severe and life threatening when they occur in individuals with

disorders of the skin, such as eczema or burns, that permit extensive local viral replication and

spread. Eczema herpeticum is a primary infection, usually with HSV-1, in a person with

chronic eczema.

In rare instances, the illness may be fatal.

E.

Encephalitis

A severe form of encephalitis may be produced by herpesvirus.

HSV-1 infections are considered the most common cause of sporadic, fatal encephalitis in the

United States. The disease carries a high mortality rate, and those who survive often have

residual neurologic defects. About half of patients with HSV encephalitis appear to have

primary infections, and the rest appear to have recurrent infection.

F.

Neonatal Herpes

HSV infection of the newborn may be acquired in utero, during birth, or after birth.

The mother is the most common source of infection in all cases.

Neonatal herpes can be acquired postnatally by exposure to either HSV-1 or HSV-2.

Sources of infection include family members and hospital personnel who are shedding virus.

About 75% of neonatal herpes infections are caused by HSV-2.

There do not appear to be any differences between the nature and severity of neonatal herpes

in premature or fullterm infants, in infections caused by HSV-1 or HSV-2, or in disease when

virus is acquired during delivery or postpartum.

Neonatal herpes infections are almost always symptomatic.

G.

Infections in Immunocompromised Hosts

Immunocompromised patients are at increased risk of developing severe HSV infections.

Epidemiology

HSV are worldwide in distribution.

The epidemiology of HSV-1 and HSV-2 differs.

HSV-1 is probably more constantly present in humans than any other virus.

Primary infection occurs early in life and is usually asymptomatic; occasionally, it produces

oropharyngeal disease (gingivostomatitis in young children, pharyngitis in young adults).

The highest incidence of HSV-1 infection occurs among children 6 months to 3 years of age.

The virus is spread by direct contact with infected saliva or through utensils contaminated

with the saliva of a virus shedder.

The source of infection for children is usually an adult with a symptomatic herpetic lesion or

with asymptomatic viral shedding in saliva.

HSV-2 is usually acquired as a sexually transmitted disease, so antibodies to this virus are

seldom found before puberty.

5

Reactivation and asymptomatic shedding occurs with both HSV-1 and HSV-2. PCR-based

studies showed frequent subclinical reactivations in immunocompetent hosts that often lasted

less than 12 hours.

Both symptomatic and asymptomatic infections provide a reservoir of virus for transmission

to susceptible persons.

Treatment

Several antiviral drugs have proved effective against HSV infections, including acyclovir,

valacyclovir, and vidarabine. All are inhibitors of viral DNA synthesis.

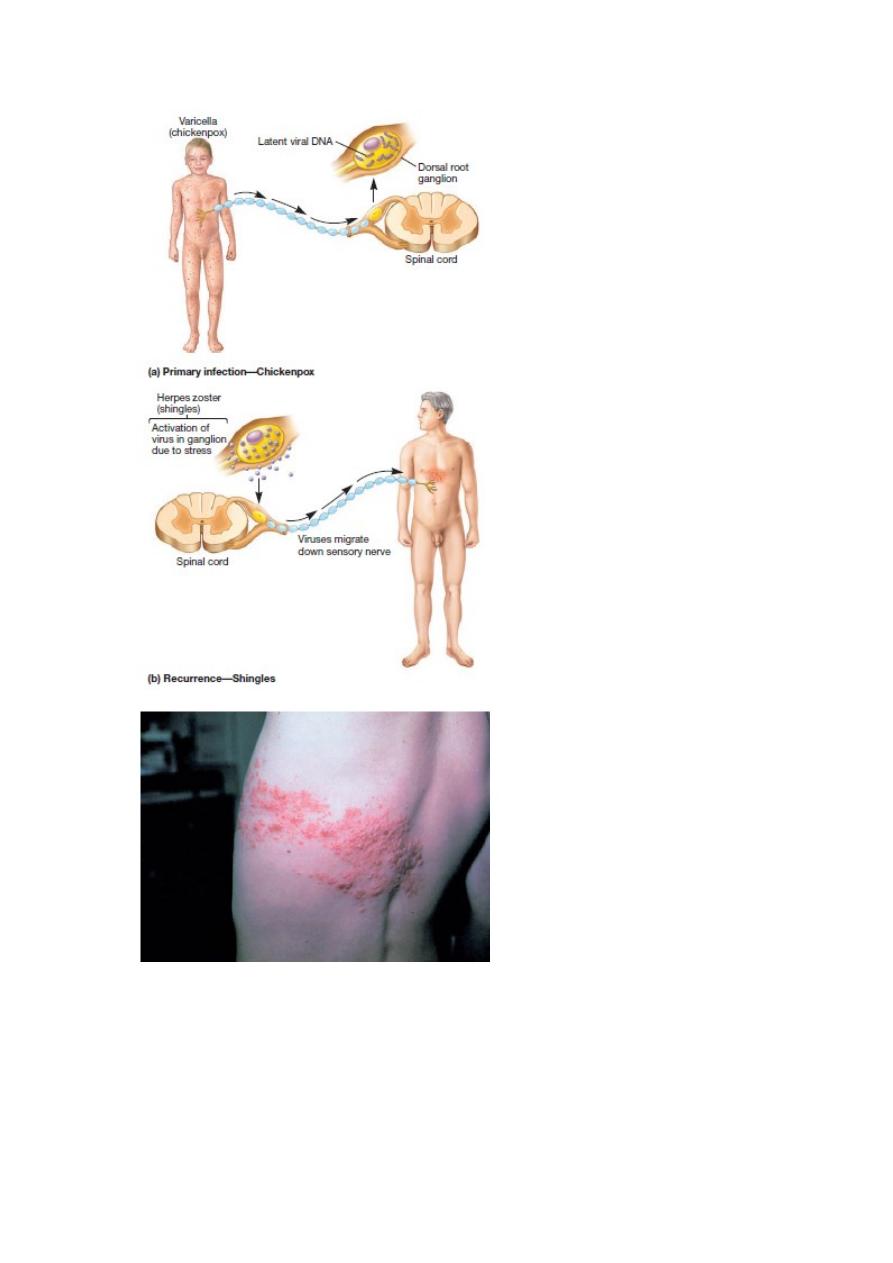

Varicella-Zoster Virus

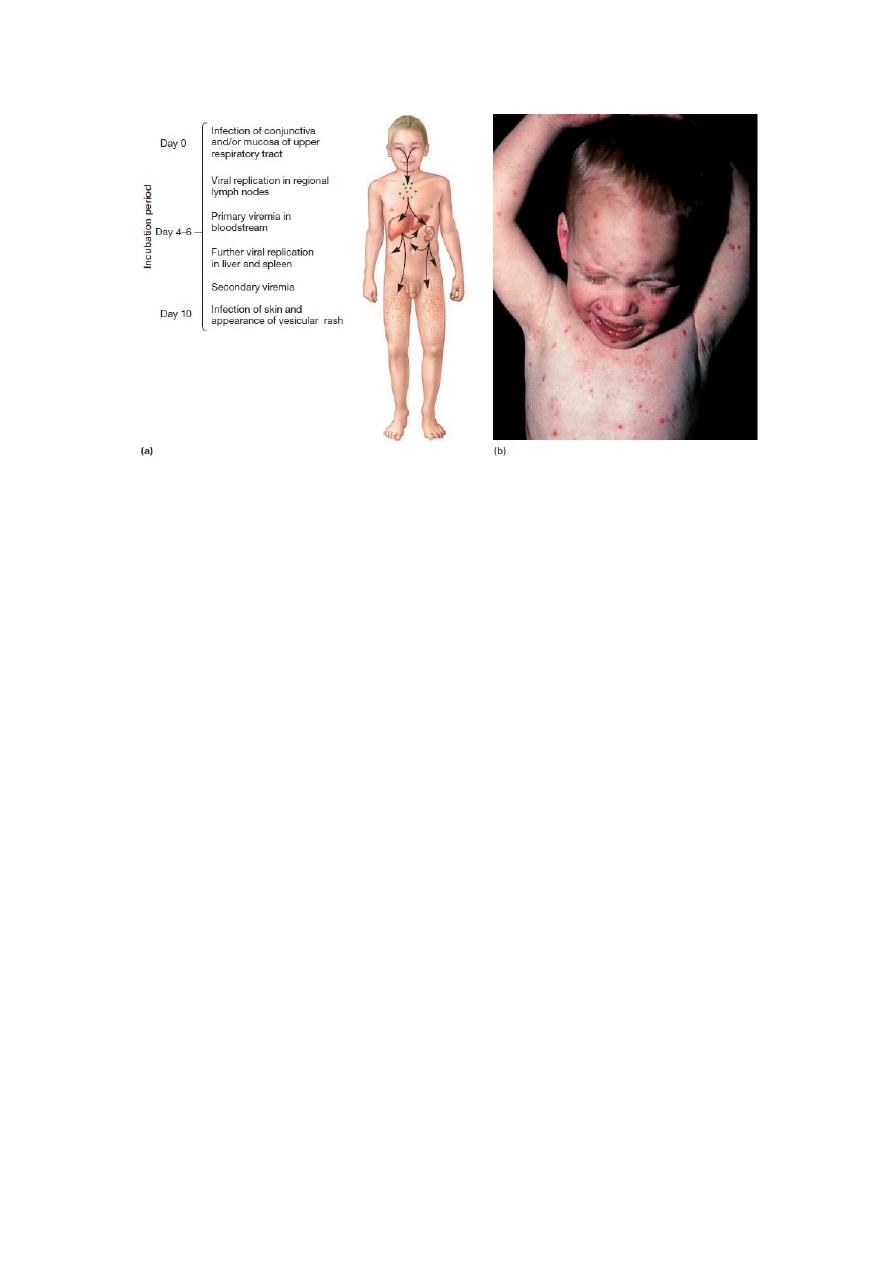

Varicella (chickenpox) is a mild, highly contagious disease, chiefly of children, characterized

clinically by a generalized vesicular eruption of the skin and mucous membranes.

The disease may be severe in adults and in immunocompromised individuals.

Zoster (shingles) is a sporadic, incapacitating disease of elderly or immunocompromised

individuals that is characterized by pain and a rash limited in distribution to the skin

innervated by a single sensory ganglion. The lesions are similar to those of varicella.

Both diseases are caused by the same virus.

Pathogenesis and Pathology

A.

Varicella

The route of infection is the mucosa of the upper respiratory tract or the conjunctiva.

It has been shown that a varicella-zoster virus-encoded protein, ORF61, antagonizes the β-

interferon pathway. This presumably contributes to the pathogenesis of viral infection.

B.

Zoster

The skin lesions of zoster are histopathologically identical to those of varicella. There is also

an acute inflammation of the sensory nerves and ganglia. Often only a single ganglion may be

involved.

Clinical Findings

A.

Varicella

Subclinical varicella is unusual. The incubation period of typical disease is 10–21 days.

Malaise and fever are the earliest symptoms, soon followed by the rash, first on the trunk and

then on the face, the limbs, and the buccal and pharyngeal mucosa in the mouth. Successive

fresh vesicles appear in crops, so that all stages of macules, papules, vesicles, and crusts may

be seen at one time.

The rash lasts about 5 days, and most children develop several hundred skin lesions.

Complications are rare in normal children, and the mortality rate is very low.

Varicella pneumonia is rare in healthy children but is the most common complication in

neonates, adults, and immunocompromised patients. It is responsible for many varicella-

related deaths.

B.

Zoster

Zoster usually occurs in persons immunocompromised as a result of disease, therapy, or

aging, but it occasionally develops in healthy young adults.

It usually starts with severe pain in the area of skin or mucosa supplied by one or more groups

of sensory nerves and ganglia.

Within a few days after onset, a crop of vesicles appears over the skin supplied by the

affected nerves.

The trunk, head, and neck are most commonly affected , with the ophthalmic division of the

trigeminal nerve involved in 10–15% of cases.

The most common complication of zoster in elderly adults is postherpetic neuralgia—

protracted pain that may continue for months.

It is especially common after ophthalmic zoster.

Visceral disease, especially pneumonia, is responsible for deaths that occur in

immunosuppressed patients with zoster (<1% of patients).

Varicella zoster central nervous system disease, most frequently meningitis, often presents

without a typical zoster rash.

6

Epidemiology

Varicella and zoster occur worldwide. Varicella (chickenpox) is highly communicable and is

a common epidemic disease of childhood (most cases occur in children younger than 10 years

of age).

Adult cases do occur.

It is much more common in winter and spring than in summer in temperate climates.

Zoster occurs sporadically, chiefly in adults and without seasonal prevalence.

About 10–20% of adults will experience at least one zoster attack during their lifetime,

usually after the age of 50 years.

Varicella spreads readily by airborne droplets and by direct contact.

A varicella patient is probably infectious (capable of transmitting the disease) from shortly

before the appearance of rash to the first few days of rash.

Contact infection is less common in zoster, perhaps because the virus is absent from the upper

respiratory tract in typical cases.

Zoster patients can be the source of varicella in susceptible children, perhaps because viral

DNA is often present in their saliva.

Varicella-zoster virus DNA has been detected using a PCR amplification method in air

samples from hospital rooms of patients with active varicella (82%) and zoster (70%)

infections.

Treatment

Varicella in normal children is a mild disease and requires no treatment.

Several antiviral compounds provide effective therapy for varicella, including acyclovir,

valacyclovir, famciclovir, and foscarnet.

Acyclovir can prevent the development of systemic disease in varicella-infected

immunosuppressed patients and can halt the progression of zoster in adults.

Cytomegalovirus

CMVs are ubiquitous herpesviruses that are common causes of human disease. CMVs are the

agents of the most common congenital infection.

Cytomegalic inclusion disease is a generalized infection of infants caused by intrauterine or

early postnatal infection with the CMVs.

The name for the classic cytomegalic inclusion disease derives from the propensity for

massive enlargement of CMV-infected cells.

The HCMV can infect any cell of the body, where it multiplies slowly and causes the host cell

to swell in size—hence the prefix cytomegalo, which means ―an enlarged cell.‖

Pathogenesis and Pathology

CMV may be transmitted from person to person in several different ways, all requiring close

contact with virus-bearing material.

There is a 4- to 8-week incubation period in normal older children and adults after viral

exposure.

The virus causes a systemic infection; it has been isolated from lung, liver, esophagus, colon,

kidneys, monocytes, and T and B lymphocytes.

The disease is an infectious mononucleosis-like syndrome, although most CMV infections are

subclinical.

Similar to all herpesviruses, CMV establishes lifelong latent infections.

Virus can be shed intermittently from the pharynx and in the urine for months to years after

primary infection.

Prolonged CMV infection of the kidney does not seem to be deleterious in normal persons.

Salivary gland involvement is common and is probably chronic.

Cell-mediated immunity is depressed with primary infections, and this may contribute to the

persistence of viral infection.

Clinical Findings

A.

Normal Hosts

Primary CMV infection of older children and adults is usually asymptomatic but occasionally

causes a spontaneous infectious mononucleosis syndrome.

7

CMV is estimated to cause 20–50% of heterophil-negative (non-EBV) mononucleosis cases.

CMV mononucleosis is a mild disease, and complications are rare.

Subclinical hepatitis is common.

In children younger than 7 years old, hepatosplenomegaly is frequently observed.

B.

Immunocompromised Hosts

Both morbidity and mortality rates are increased with primary and recurrent CMV infections

in immunocompromised individuals.

Pneumonia is a frequent complication.

CMV often causes disseminated disease in untreated AIDS patients; gastroenteritis and

chorioretinitis are common problems, the latter often leading to progressive blindness.

C.

Congenital and Perinatal Infections

Congenital infection may result in death of the fetus in utero.

Cytomegalic inclusion disease of newborns is characterized by involvement of the central

nervous system and the reticuloendothelial system.

Treatment

Drug treatments of CMV infections have shown some encouraging results.

Ganciclovir, a nucleoside structurally related to acyclovir, has been used successfully to treat

life-threatening CMV infections in immunosuppressed patients.

The severity of CMV retinitis, esophagitis, and colitis is reduced by ganciclovir.

Epstein-Barr Virus

EBV is a ubiquitous herpesvirus that is the causative agent of acute infectious mononucleosis

and is associated with nasopharyngeal carcinoma, Burkitt lymphoma, Hodgkin and non-

Hodgkin lymphomas, other lymphoproliferative disorders in immunodeficient individuals,

and gastric carcinoma.

Clinical Findings

Most primary infections in children are asymptomatic.

In adolescents and young adults, the classic syndrome associated with primary infection is

infectious mononucleosis (~50% of infections).

EBV is also associated with several types of cancer.

A.

Infectious Mononucleosis

After an incubation period of 30–50 days, symptoms of headache, fever, malaise, fatigue, and

sore throat occur.

Enlarged lymph nodes and spleen are characteristic.

Some patients develop signs of hepatitis.

The typical illness is self-limited and lasts for 2–4 weeks.

During the disease, there is an increase in the number of circulating white blood cells, with a

predominance of lymphocytes.

Many of these are large, atypical T lymphocytes.

Low-grade fever and malaise may persist for weeks to months after acute illness.

Complications are rare in normal hosts.

B.

Cancer

EBV is associated with Burkitt lymphoma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, Hodgkin and non-

Hodgkin lymphomas, and gastric carcinoma.

EBV-associated posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders are a complication for

immunodeficient patients.

Sera from patients with Burkitt lymphoma or nasopharyngeal carcinoma contain elevated

levels of antibody to virus-specific antigens, and the tumor tissues contain EBV DNA and

express a limited number of viral genes.

Burkitt lymphoma is a tumor of the jaw in African children and young adults.

Most African tumors (>90%) contain EBV DNA and express EBNA1 antigen.

In other parts of the world, only about 20% of Burkitt lympho-mas contain EBV DNA.

It is speculated that EBV may be involved at an early stage in Burkitt lymphoma by

immortalizing B cells.

Malaria, a recognized cofactor, may foster enlargement of the pool of EBV-infected cells.

8

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma is a cancer of epithelial cells and is common in males of Chinese

origin.

Genetic and environmental factors are believed to be important in the development of

nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

Treatment

There is no EBV vaccine available.

Acyclovir reduces EBV shedding from the oropharynx during the period of drug

administration, but it does not affect the number of EBV-immortalized B cells.

Acyclovir has no effect on the symptoms of mononucleosis and is of no proved benefit in the

treatment of EBV-associated lymphomas in immunocompromised patients.

Human Herpesvirus 6

The T-lymphotropic HHV-6 was first recognized in 1986.

Initial isolations were made from cultures of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients

with lymphoproliferative disorders.

Properties of the Virus

The genetic arrangement of the HHV-6 genome resembles that of human CMV.

HHV-6 appears to be unrelated antigenically to the other known human herpesviruses except

for some limited crossreactivity with HHV-7.

Isolates of HHV-6 segregate into two closely related but distinct antigenic groups(designated

A and B).

Cells in the oropharynx must become infected because virus is present in saliva.

It is not known which cells in the body become latently infected.

Human CD46 is the cellular receptor for the virus.

Epidemiology and Clinical Findings

Infections with HHV-6 typically occur in early childhood.

This primary infection causes exanthem subitum (roseola infantum, or “sixth disease”), the

mild common childhood disease characterized by a high fever and skin rash.

The 6B variant appears to be the cause of this disease.

The virus is associated with febrile seizures in children.

The mode of transmission of HHV-6 is presumed to be via oral secretions.

The fact that it is a ubiquitous agent suggests that it must be shed into the environment from

an infected carrier.

Infections persist for life. Reactivation appears to be common in transplant patients and

during pregnancy.

HUMAN HERPESVIRUS 7

A T-lymphotropic human herpesvirus, designated HHV-7, was first isolated in 1990 from

activated T cells recovered from peripheral blood lymphocytes of a healthy individual.

HHV-7 is immunologically distinct from HHV-6, although they share about 50% homology

at the DNA level.

HHV-7 appears to be a ubiquitous agent, with most infections occurring in childhood but later

than the very early age of infection noted with HHV-6.

Persistent infections are established in salivary glands, and the virus can be isolated from

saliva of most individuals.

In a longitudinal study of healthy adults, 75% of subjects excreted infectious virus in saliva

one or more times during a 6-month observation period.

Similar to HHV-6, primary infection with HHV-7 has been linked with roseola infantum in

infants and young children. Any other disease associations of HHV-7 remain to be

established.

Human Herpesvirus 8

A new herpesvirus, designated HHV-8 and also called KSHV, was first detected in 1994 in

Kaposi sarcoma specimens.

KSHV is lymphotropic and is more closely related to EBV and herpesvirus saimiri than to

other known herpesviruses.

9

KSHV is not as ubiquitous as other herpesviruses; about 5% of the general population in the

United States and northern Europe have serologic evidence of KSHV infection.

Contact with oral secretions is likely the most common route of transmission.

The virus can also be transmitted sexually, vertically, by blood, and through organ

transplants.

Viral DNA has also been detected in breast milk samples in Africa.

Infections are common in Africa (>50%) and are acquired early in life.

Foscarnet, famciclovir, ganciclovir, and cidofovir have activity against KSHV replication.

The level of KSHV replication and rate of new Kaposi sarcomas are markedly reduced

in HIV-positive patients on effective antiretroviral therapy, probably reflecting reconstituted

immune surveillance against KSHV-infected cells.

B Virus

Herpes B virus of Old World monkeys is highly pathogenic for humans.

Transmissibility of virus to humans is limited, but infections that do occur are associated with

a high mortality rate (~60%).

B virus disease of humans is an acute ascending myelitis and encephalomyelitis.

As with all herpesviruses, B virus establishes latent infections in infected hosts.

Cytopathic effects are similar to those of HSV.

B virus infections seldom cause disease in rhesus monkeys.

B virus infections in humans usually result from a monkey bite, although infection by the

respiratory route or ocular splash exposure is possible.

The striking feature of B virus infections in humans is the very strong propensity to cause

neurologic disease.

Many survivors are left with neurologic impairment.

Epidemiology and Clinical Findings

B virus is transmitted by direct contact with virus or virus-containing material.

Transmission occurs among Macaca monkeys, between monkeys and humans, and rarely

from human to human.

Virus may be present in saliva, conjunctival and vesicular fluids, genital areas, and feces of

monkeys.

Respiratory transmission can occur.

Infection in the natural host is rarely associated with obvious disease.

Animal workers and persons handling macaque monkeys, including medical researchers,

veterinarians, pet owners, and zoo workers, are at risk of acquiring B virus infection.

Individuals having intimate contact with animal workers exposed to the monkeys are also at

some risk.

Treatment and Control

There is no specific treatment after the clinical disease is manifest.

However, treatment with acyclovir is recommended immediately after exposure.

γ

-Globulin has not proved to be effective treatment for human B virus infections.

No vaccine is available.

10

Chickenpox (Varicella).

(a) Course of infection.

(b) Typical vesicular skin rash. This rash occurs all over the body, but is

heaviest on the trunk and diminishes in intensity toward the periphery.

11

©

Pathogenesis of the Varicella Zoster Virus.

(a) After an initial infection with varicella (chickenpox), the viruses migrate up

sensory peripheral nerves to their dorsal root ganglia, producing a latent infection.

(b)When a person becomes immunocompromised or is under psychological or

physiological stress, the viruses may be activated.

(c) They migrate down sensory nerve axons, initiate viral replication, and produce

painful vesicles. Since these vesicles usually appear around the trunk of the body, the

name zoster (Greek for girdle) was used.

12

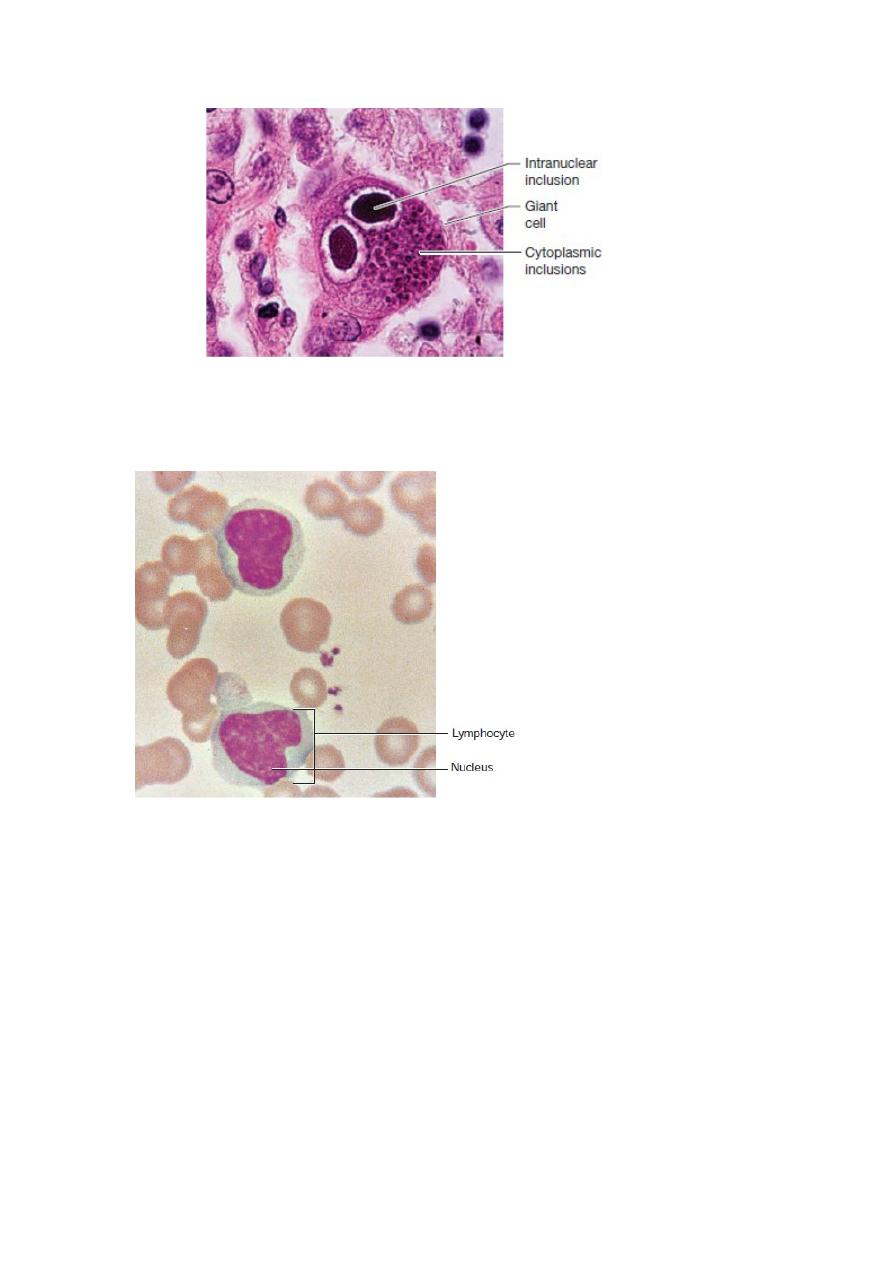

Cytomegalovirus Inclusion Disease.

Light micrograph of a giant cell in a lung section infected with the cytomegalovirus (_480).

The intranuclear inclusion body has a typical “owl-eyed” appearance because of its surrounding clear

halo.

Sometimes virus inclusions also are visible in the cytoplasm.

Evidence of Epstein-Barr Infection in the

Blood Smear of a Patient with Infectious Mononucleosis.

Note the abnormally large lymphocytes containing indented nuclei

with light discolorations.