1

Human Diseases Caused by Viruses

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is a highly contagious viral disease caused by a

novel coronavirus, known as the SARS-associate coronavirus (SARS-CoV). Coronaviruses

are positive-strand RNA viruses.

Coronaviruses are relatively large (120–150 nm), composed of RNA within a helical

nucleocapsid, surrounded by a membranous envelope.

Large peplomers (spikes) protrude from the envelope to aid in attachment and entry into host

cells.

The protruding peplomers extend from the oval-to-spherical virion to give the illusion of a

halo, or corona, around the virus. The virus causes a febrile (>100.4°F or >38°C) lower

respiratory track illness.

Sudden, severe illness in otherwise healthy individuals is a hallmark of the disease.

Other symptoms may include headache; mild, flu-like discomfort; and body aches.

SARS patients may develop a dry cough after a few days, and most will develop pneumonia.

About 10 to 20% of patients have diarrhea. If not detected early, this disease can be fatal

even with supportive care.

SARS is transmitted by close contact with respiratory secretions (droplet spread).

The initial outbreak of SARS appears to have originated in China in late 2002 and it spread

rapidly to at least 29 other countries by summer 2003.

The outbreak resulted in 8,098 persons with possible SARS, including 744 deaths being

reported by the World Health Organization.

There were 373 possible SARS cases in the United States; however, SARS-CoV

identification has been confirmed in only 8 of them. Seven of the eight cases were likely due

to exposure during international travel and the eighth case was probably due to exposure to

one of the other seven.

The 2003 SARS epidemic demonstrated to the world the ease with which a viral infectious

agent can spread.

Rapid detection and prevention measures were pursued during and after the outbreak.

Diligent screening for signs of fever or respiratory disease at airports and the initiation of

SARS-CoV vaccine trials are two examples of protective measures.

No specific treatment is currently approved.

**

Smallpox (Variola)

Smallpox (variola) is a highly contagious illness of humans caused by the orthopoxvirus,

variola major.

Characteristic symptoms of infection include acute onset of fever

≥

101°F (38.3°C) followed

by a rash that features firm, deep-seated vesicles or pustules in the same stage of development

without other apparent cause.

The variola virus belongs to the family Poxviridae, which includes vaccinia (cowpox and also

the smallpox vaccine virus), monkeypox virus, and molluscum contagiosum virus.

Humans are the only natural hosts of variola.

The virion is large, brick-shaped, and contains a dumbell-shaped core. Interestingly, the

size of the smallpox virus (300 by 250 to 200 nm) is slightly larger than that of some of the

smallest bacteria—for example, Chlamydia.

The genome inside the core consists of a single, linear molecule of double-stranded DNA and

replicates in the host cell’s cytoplasm.

Smallpox was once one of the most prevalent of all diseases. It was a universally dreaded

scourge for more than 3 millennia, with case fatality rates of 20 to 50%.

First subjected to some control by variolation in tenth-century India and China, it was

gradually suppressed in the industrialized world after Edward Jenner’s 1796 landmark

discovery that infection with the harmless cowpox (vaccinia) virus renders humans immune

to the smallpox virus.

2

Since the advent of immunization with the vaccinia virus, and because of concerted efforts by

the World Health Organization, smallpox has been eradicated throughout the world—the

greatest public health achievement ever. (The last case from a natural infection occurred in

Somalia in 1977.) Eradication was possible because smallpox has obvious clinical features,

virtually no asymptomatic carriers, only human hosts as reservoirs, and a short period of

infectivity (3 to 4 weeks). The disease was successfully eliminated by a global immunization

effort to prevent the spread of smallpox until no new cases developed.

There are two clinical forms of smallpox. Disease caused by

Variola major

is more severe and

the most common form of smallpox, with a more extensive rash and higher fever.

Historically, this form of smallpox had an overall fatality rate of about 33%; with significant

morbidity in those who did not die.

Variola

minor

is a less common form of smallpox, with much less severe disease and death

rates of 1% or less.

Variola is generally transmitted by direct and fairly prolonged face-to-face contact.

It also can be spread through direct contact with infected bodily fluids or contaminated

objects such as bedding or clothing.

Smallpox has been reported to spread through the air in enclosed settings such as buildings,

buses, and trains.

Smallpox is not known to be transmitted by insects or animals.

The virus enters the respiratory tract, seeding the mucous membranes and passing rapidly into

regional lymph nodes.

The average incubation period is 12 to 14 days but can range from 7 to 17 days. During this

time, the virus multiplies in the monocyte-macrophage system, but the host is not contagious.

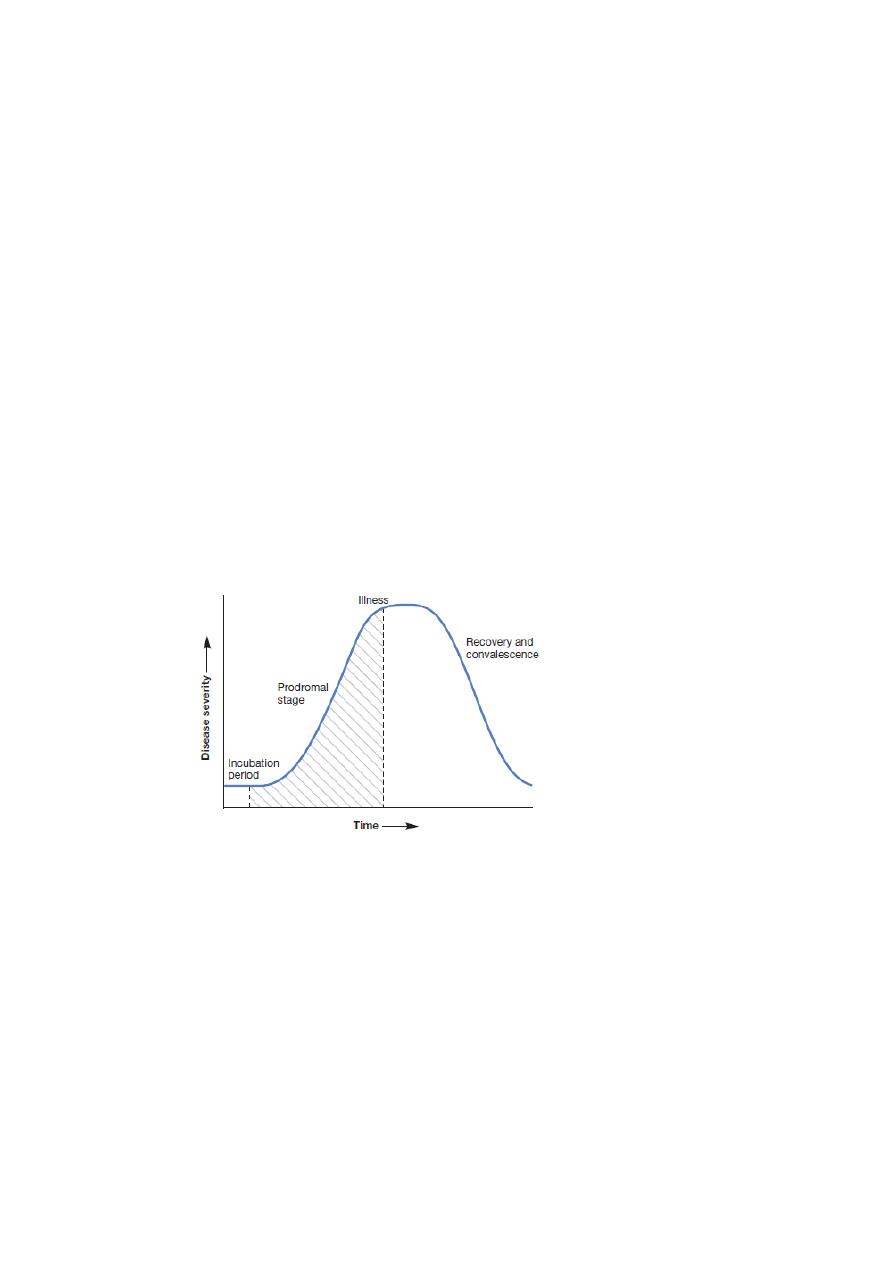

Another brief period of viremia precedes the prodromal phase (see figure 1).

Figure 1 The Course of an Infectious Disease.

Most infectious diseases occur in four stages.The duration of each stage is a characteristic feature of

each disease.

This is one of the major reasons the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study the

course of infectious diseases.

The shaded area represents when a disease is typically communicable.

The prodromal phase lasts for 2 to 4 days and is characterized by malaise, severe head and

body aches, occasional vomiting, and fever (over 40°C), all beginning abruptly.

During the prodromal phase, the mucous membranes in the mouth and pharynx become

infected, resulting is a rash of small, red spots.

These spots develop into open sores that spread large amounts of the virus into the mouth and

throat. At this time, the person is highly contagious.

The virus then invades the capillary epithelium of the skin, leading to the development of the

following sequence of lesions in/on the skin: eruptions, papules, vesicles, pustules, crusts, and

desquamation (figure 2).

3

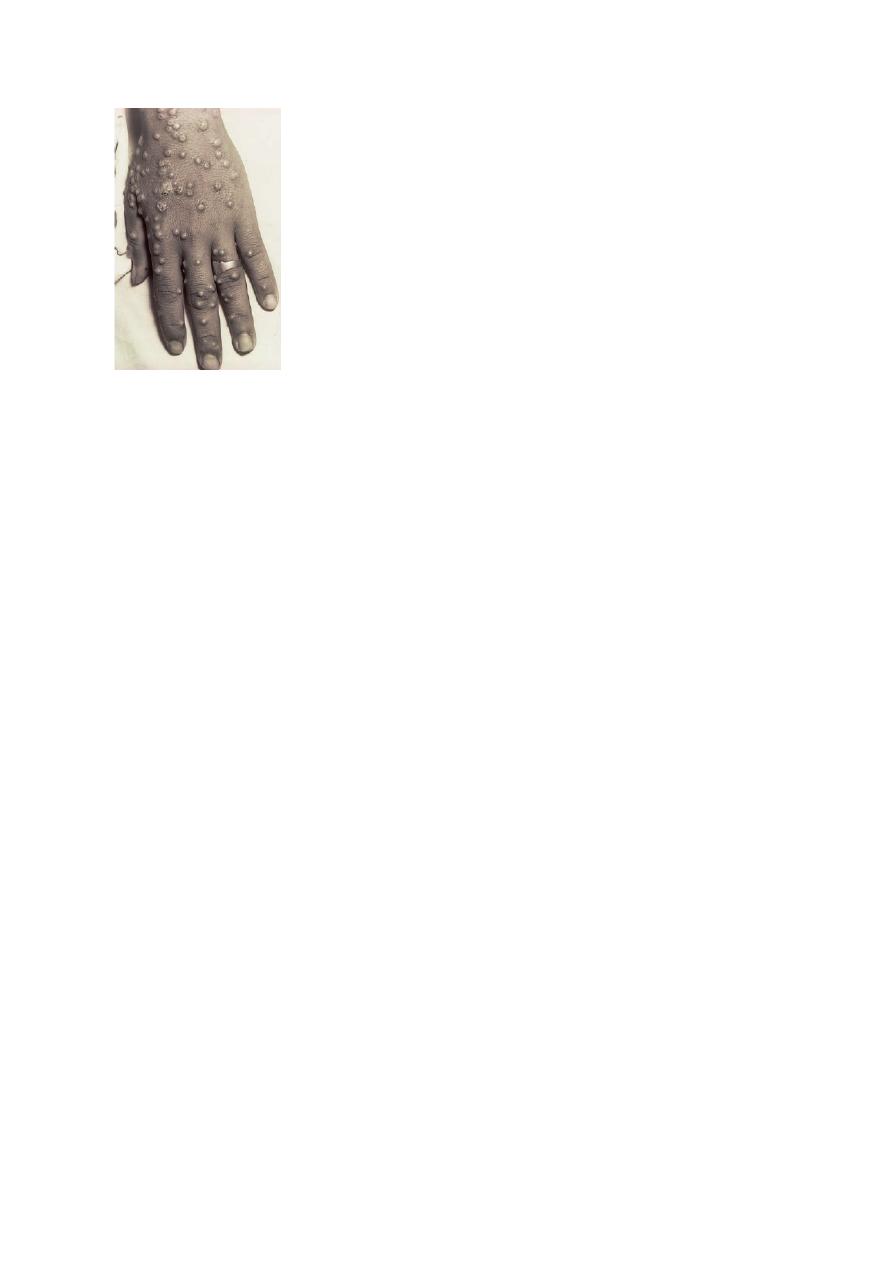

Figure 2 Smallpox.

Back of hand showing single crop of smallpox vesicles.

The rash appears on the face, spreads to the arms and legs, and then the hands and feet.

Usually the rash spreads over the body within 24 hours.

By the third day of the rash, it forms raised bumps.

By the fourth day, the bumps fill with a thick, opaque fluid and often have a depression in the

center that looks like a bellybutton. (This is a major distinguishing characteristic of smallpox,

as compared to other diseases that exhibit rashes.)

The fever usually declines as the rash appears but rises and is sustained from the time the

vesicles form until they crust over.

Oropharyngeal and skin lesions contain abundant virus particles, particularly early in the

disease process.

Death from smallpox is due to toxemia associated with immune-mediated blood clots and

elevated blood pressure.

Protection from smallpox is through vaccination (once referred to as variolation).

The smallpox vaccine is a live virus immunization using the related vaccina virus.

The vaccine is given using a bifurcated (two-pronged) needle that is dipped into the vaccine.

The bifurcated needle retains a droplet of the vaccine so that pricking the skin allows vaccinia

entry into the skin.

This immunization practice causes a sore spot and one or two droplets of blood to form. If the

vaccination is successful, a red and itchy bump develops at the vaccine site that becomes a

large blister, filled with pus. The blister will dry and form a scab that falls off, leaving a small

scar. People vaccinated for the first time have a stronger reaction than those who are

revaccinated.

Routine immunization for smallpox was discontinued in the United States once global

eradication was confirmed.

Today, smallpox vaccination is controversial in light of its unknown efficacy in bioterrorism

prevention and potential side-effects.

Unlike most vaccines, when smallpox vaccine is given very early in the incubation period,

it can markedly attenuate or even prevent clinical manifestations.

Strict respiratory and contact isolation is important.

There is great concern that the smallpox virus could be used as a weapon by terrorists.

An accidental or deliberate release of smallpox virus would be catastrophic in an

unimmunized population and could cause a major pandemic. Because smallpox vaccination

has not been performed routinely since about 1972, there is now a large population of

susceptible persons. Currently, less than half the world’s population has been exposed to

either smallpox (variola virus) or to the vaccine. Thus if an outbreak occurred, prompt

recognition and institution of control measures would be paramount.

4

Poliomyelitis

Poliomyelitis [Greek polios, gray, and myelos, marrow or spinal cord], polio, or infantile

paralysis is caused by the poliovirus, a member of the family Picornaviridae .

The poliovirus is a naked, positive-strand RNA virus with three different serotypes—P1, P2,

and P3.

The virus is very stable, especially at acidic pH, and can remain infectious for relatively long

periods in food and water—its main routes of transmission.

The average incubation period is 6 to 20 days.

Once ingested, the virus multiplies in the mucosa of the throat and/or small intestine. From

these sites the virus invades the tonsils and lymph nodes of the neck and terminal portion of

the small intestine. Generally, there are either no symptoms or a brief illness characterized by

fever, headache, sore throat, vomiting, and loss of appetite. The virus sometimes enters the

bloodstream and causes a viremia. In most cases (more than 99%), the viremia is transient and

clinical disease does not result. In the minority of cases (less than 1%), the viremia persists

and the virus enters the central nervous system and causes paralytic polio.

The virus has a high affinity for anterior horn motor nerve cells of the spinal cord. Once

inside these cells, it multiplies and destroys the cells; this results in motor and muscle

paralysis.

Since the licensing of the formalin-inactivated Salk vaccine (1955) and the attenuated virus

Sabin vaccine (1962), the incidence of polio has decreased markedly.

No endogenous reservoir of polioviruses exists in the United States. An on-going global effort

to eliminate polio has been very successful.

However, sporadic cases were reported in 2005, mostly in areas where religious views and

misinformation diminish vaccination efforts.

Nonetheless, it is likely that polio will be the next human disease to be completely eradicated.

**

Ebola and Marburg Hemorrhagic Fevers

Viral hemorrhagic fever (VHF)

is the term used to describe a severe, multisystem syndrome

caused by several distinct viruses.

Characteristically, the overall host vascular system is damaged, resulting in vascular leakage

(hemorrhage) and dysfunction (coagulopathy).

Ebola hemorrhagic fever

is caused by the Ebola virus, first recognized near the Ebola River

in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in Africa.

The virus is a member of a family of negative-strand RNA viruses called the Filoviridae.

Four Ebola subtypes are known. Ebola-Zaire, Ebola-Sudan, and Ebola-Ivory Coast cause

disease in humans. The fourth, Ebola-Reston, appears to only cause disease in nonhuman

primates, and unlike the others, is spread by aerosol transmission as well as by contact

with body fluids.

Infection with Ebola is severe and approximately 80% fatal.

The incubation period for the hemorrhagic fever caused by Ebola ranges from 2 to 21 days

and is characterized by abrupt fever, headache, joint and muscle aches, sore throat, and

weakness, followed by diarrhea, vomiting, and stomach pain.

Signs of infection include rash, red eyes, bleeding, and hiccups, while symptoms alert of

internal hemorrhage.

The reservoir of Ebola virus appears to be at least three species of fruit bats

that are native only to Africa.

Contact with an infected animal (bats, apes, or other primates) and subsequent transmission to

other humans likely initiates an outbreak.

Transmission can be from direct contact with the blood and/or secretions from an infected

person or clinical samples.

Exposure can also occur through contact with bodies of Ebola victims.

There is no standard treatment for Ebola infection.

Patients receive supportive therapy. This consists of balancing patients’ fluids and

electrolytes, maintaining their oxygen status and blood pressure, and treating them for any

5

complicating infections. Experimental vaccines are currently being evaluated and show

promise in nonhuman primate models.

Marburg hemorrhagic fever

is caused by a genetically unique RNA virus in the Filoviridae

family.

Marburg fever is a rare, severe type of hemorrhagic fever that affects both humans

and nonhuman primates. Recognition of this virus led to the creation of the Filoviridae

family.

Marburg virus was first recognized in 1967, when outbreaks of hemorrhagic fever occurred

simultaneously in laboratories in Marburg and Frankfurt, Germany and in

Belgrade, Yugoslavia (now Serbia). A total of 32 people became ill; they included laboratory

workers as well as several medical personnel and family members who had cared for them.

The first people infected had been exposed to African green monkeys or their tissues. In

Marburg, the monkeys had been imported for research and to prepare polio vaccine.

Marburg virus is indigenous to Africa, but its specific origin is yet unknown.

A definitive animal host is also unknown.

The average incubation period for Marburg hemorrhagic fever is 5 to 10 days.

The disease symptoms are abrupt, marked by fever, chills, headache, and myalgia.

A maculopapular rash, most prominent on the chest, back, and stomach,

typically appears around the fifth day after the onset.

Nausea, vomiting, chest pain, sore throat, abdominal pain, and diarrhea may also occur in

infected patients.

Symptoms become increasingly severe and may include jaundice, delirium, liver failure,

pancreatitis, severe weight loss, shock, and multi-organ dysfunction.

A specific treatment for this disease is unknown. However, supportive hospital therapy should

be utilized. This includes balancing the patient’s fluids and electrolytes, maintaining oxygen

status and blood pressure, replacing lost blood and clotting factors, and treating for other

complicating infections.

The deadly Marburg virus was first isolated in 1967 at the Institute for Hygiene and Microbiology in

Marburg,Germany.

Rabies

Rabies [Latin rabere, rage or madness] is caused by a number of different strains of highly

neurotropic viruses. Most belong to a single serotype in the genus Lyssavirus [Greek lyssa,

rage or rabies], family Rhabdoviridae. The bullet-shaped virion contains a negative-

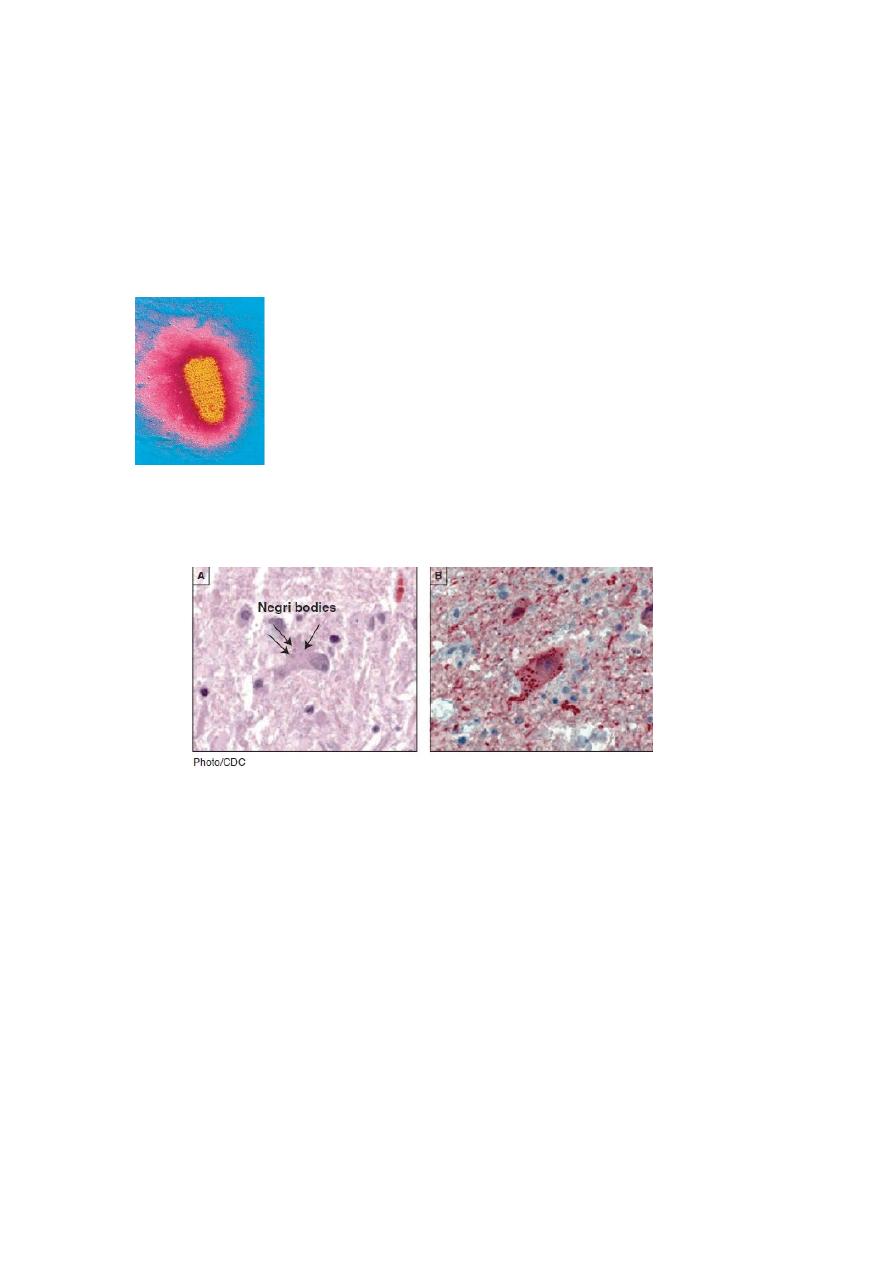

strand RNA genome (figure 3).

Rabies has been the object of human fascination, torment, and fear since the disease was

first recognized. Prior to Pasteur’s development of an antirabies vaccine, few words were

more terrifying than the cry of ―mad dog!‖

Improvements in prevention during the past 50 years have led to almost complete elimination

of indigenously acquired rabies in the United States where rabies is primarily a disease of

feral animals.

6

Most wild animals can become infected with rabies, but susceptibility varies according to

species.

Foxes, coyotes, and wolves are the most susceptible; intermediate are skunks, raccoons,

insectivorous bats, and bobcats; while opossums are quite resistant . Worldwide, almost all

cases of human rabies are attributed to dog bites. In developing countries where canine

rabies is still endemic, rabies accounts for up to 40,000 deaths per year.

Occasionally, other domestic animals are responsible for transmission of rabies to humans. It

should be noted, however, that not all rabid animals exhibit signs of agitation and aggression

(known as furious rabies).

In fact, paralysis (dumb rabies) is the more common sign exhibited by rabid animals.

The virus multiplies in the salivary glands of an infected host.

It is transmitted to humans or other animals by the bite of an infected animal whose saliva

contains the virus; by aerosols of the virus that can be spread in caves where bats dwell; or by

contamination of scratches, abrasions, open wounds, and mucous membranes with saliva

from an infected animal.

After inoculation, a region of the virions’ glycoprotein envelope spike attaches to the plasma

membrane of nearby skeletal muscle cells, the virus enters the cells, and multiplication of the

virus occurs.

When the concentration of the virus in the muscle is sufficient, the virus enters the nervous

system through unmyelinated sensory and motor terminals; the binding site is the nicotinic

acetylcholine receptor.

The virus spreads by retrograde axonal flow at 8 to 20 mm per day until it reaches the spinal

cord, when the first specific symptoms of the disease—pain or paresthesia at the wound site—

may occur.

A rapidly progressive encephalitis develops as the virus quickly disseminates through the

central nervous system.

The virus then spreads throughout the body along the peripheral nerves, including those in the

salivary glands, where it is shed in the saliva.

Within brain neurons the virus produces characteristic Negri bodies, masses of viruses or

unassembled viral subunits that are visible in the light microscope.

In the past, diagnosis of rabies consisted solely of examining nervous tissue for the presence

of these bodies. Today diagnosis is based on direct immunof luorescent

antibody (DFA) of brain tissue, virus isolation, detection of Negri bodies, and a rapid rabies

enzyme-mediated immunodiagnosis test.

Symptoms of rabies usually begin 2 to 16 weeks after viral exposure and include anxiety,

irritability, depression, fatigue, loss of appetite, fever, and a sensitivity to light and sound.

The disease quickly progresses to a stage of paralysis. In about 50% of all

cases, intense and painful spasms of the throat and chest muscles occur when the victim

swallows liquids.

The mere sight, thought, or smell of water can set off spasms.

Consequently, rabies has been called hydrophobia (fear of water).

Death results from destruction of the regions of the brain that regulate breathing.

Safe and effective vaccines (human diploid-cell rabies vaccine HDCV [Imovax Rabies] or

rabies vaccine adsorbed [RVA]) against rabies are available; however, to be effective they

must be given soon after the person has been infected.

Veterinarians and laboratory personnel, who have a high risk of exposure to rabies, usually

are immunized every 2 years and tested for the presence of suitable antibody titer.

About 30,000 people annually receive this treatment.

In the United States fewer than 10 cases of rabies occur yearly in humans, although about

8,000 cases of animal rabies are reported each year from various sources .

Prevention and control involves pre-exposure vaccination of dogs and cats, postexposure

vaccination of humans, and pre-exposure vaccination of humans at special risk (persons

spending a month or more in countries where rabies is common in dogs).

Some states and countries (Hawaii and Great Britain, for example) retain their rabies-free

status by imposing quarantine periods on any entering dog or cat.

7

If an asymptomatic, unvaccinated dog or cat bites a human, the animal is typically confined

and observed by a veterinarian for at least 10 days.

If the animal shows no signs of rabies in that time, it is determined to be uninfected.

Animals demonstrating signs of rabies are killed and brain tissue submitted for rabies testing.

Postexposure prophylaxis—rabies immune globulin for passive immunity and rabies vaccine

for active immunity—is initiated to exploit the relatively long incubation period of the virus.

This is usually recommended for anyone bitten by one of the common reservoir species

(raccoons, skunks, foxes, and bats), unless it is proven that the animal was uninfected.

Once symptoms of rabies develop in a human, death usually occurs.

Figure 3 Rabies.

Electron micrograph of the rabies virus (yellow) (ˣ36,700).Note the bullet shape. The external surface of

the virus contains spikelike glycoprotein projections that bind specifically to cellular receptors.

Figure 4

Histopathologic examination of central nervous system tissue from autopsy of a decedent

with suspected rabies infection, showing neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions (Negri bodies) after

hematoxylin and eosin staining (A) and rabies virus antigen (red) after immunohistochemical staining

(B).