Diagnosis and Treatment

of Furcation‐Involved Teeth

Diagnosis and Treatment

of Furcation‐Involved Teeth

Edited by Luigi Nibali

Senior Clinical Lecturer

Centre for Immunobiology and Regenerative Medicine

Centre for Oral Clinical Research, Institute of Dentistry

Barts and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry

Queen Mary University of London (QMUL), London, UK

Honorary Associate Professor, University of Hong Kong

This edition first published 2018

© 2018 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted,

in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as

permitted by law. Advice on how to obtain permission to reuse material from this title is available at

http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

The right of Luigi Nibali to be identified as the author of the editorial material in this work has been asserted

in accordance with law.

Registered Offices

John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, USA

John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

Editorial Office

9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK

For details of our global editorial offices, customer services, and more information about Wiley products visit us

at www.wiley.com.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats and by print‐on‐demand. Some content that

appears in standard print versions of this book may not be available in other formats.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty

The contents of this work are intended to further general scientific research, understanding, and discussion only

and are not intended and should not be relied upon as recommending or promoting scientific method, diagnosis, or

treatment by physicians for any particular patient. In view of ongoing research, equipment modifications, changes

in governmental regulations, and the constant flow of information relating to the use of medicines, equipment, and

devices, the reader is urged to review and evaluate the information provided in the package insert or instructions

for each medicine, equipment, or device for, among other things, any changes in the instructions or indication of

usage and for added warnings and precautions. While the publisher and authors have used their best efforts in

preparing this work, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the

contents of this work and specifically disclaim all warranties, including without limitation any implied warranties of

merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives,

written sales materials or promotional statements for this work. The fact that an organization, website, or product

is referred to in this work as a citation and/or potential source of further information does not mean that the

publisher and authors endorse the information or services the organization, website, or product may provide or

recommendations it may make. This work is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in

rendering professional services. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation.

You should consult with a specialist where appropriate. Further, readers should be aware that websites listed in

this work may have changed or disappeared between when this work was written and when it is read. Neither the

publisher nor authors shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited

to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

Library of Congress Cataloging‐in‐Publication Data

Names: Nibali, Luigi, 1978– editor.

Title: Diagnosis and treatment of furcation-involved teeth / edited by Luigi Nibali.

Description: Hoboken, NJ : Wiley, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2018010570 (print) | LCCN 2018011380 (ebook) | ISBN 9781119270669 (pdf) |

ISBN 9781119270676 (epub) | ISBN 9781119270652 (hardback)

Subjects: | MESH: Furcation Defects–diagnosis | Furcation Defects–therapy | Models, Animal

Classification: LCC RK450.P4 (ebook) | LCC RK450.P4 (print) | NLM WU 242 | DDC 617.6/32–dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018010570

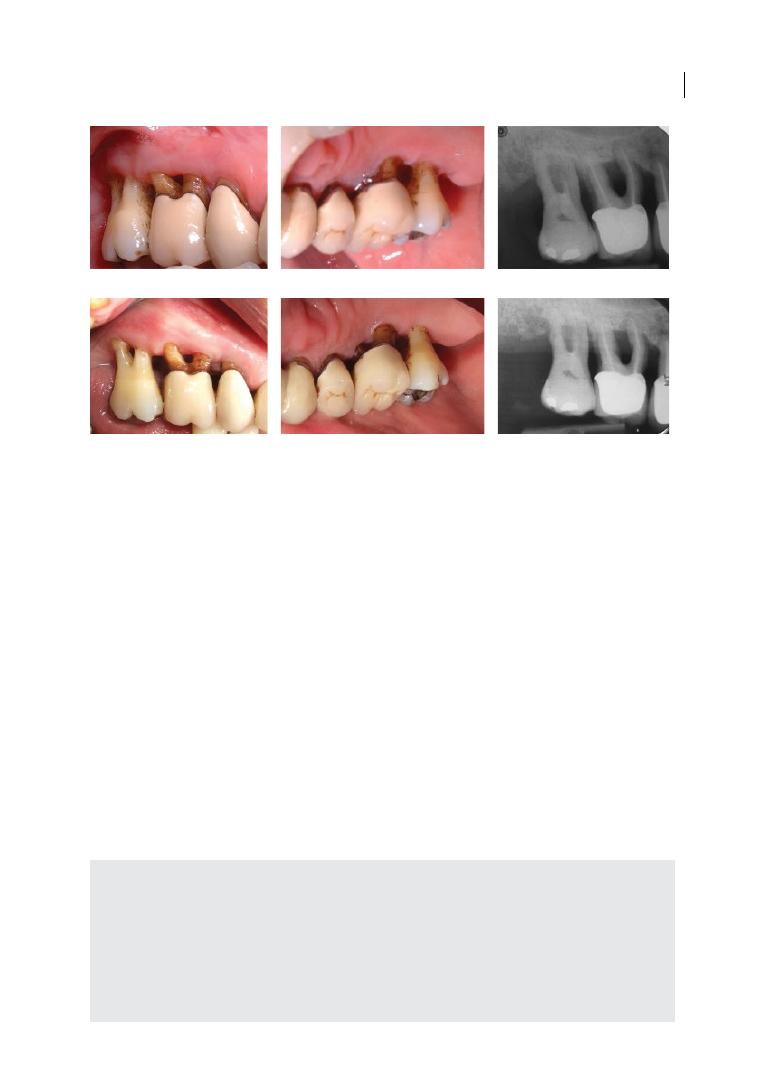

Cover image: (Main, top left and middle images) © Luigi Nibali; (Top right image) © Roberto Rotundo

Cover design: Wiley

Set in 10/12pt Warnock by SPi Global, Pondicherry, India

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Chapter No.: 1 Title Name: <TITLENAME>

ftoc.indd

Comp. by: R. RAMESH Date: 14 May 2018 Time: 04:18:23 PM Stage: Revises1 WorkFlow:

<WORKFLOW>

Page Number: v

v

List of Contributors

vii

Foreword

ix

Preface

xi

About the Companion Website

xiii

1 Anatomy of Multi‐rooted Teeth and Aetiopathogenesis of the Furcation Defect

1

Bernadette Pretzl

2 Clinical and Radiographic Diagnosis and Epidemiology of Furcation Involvement

15

Peter Eickholz and Clemens Walter

3 How Good are We at Cleaning Furcations? Non‐surgical and Surgical Studies

33

Jia‐Hui Fu and Hom‐Lay Wang

4

Furcation: The Endodontist’s View

55

Federica Fonzar and Riccardo Fabian Fonzar

5 Why do We Really Care About Furcations? Long‐term Tooth Loss Data

91

Luigi Nibali

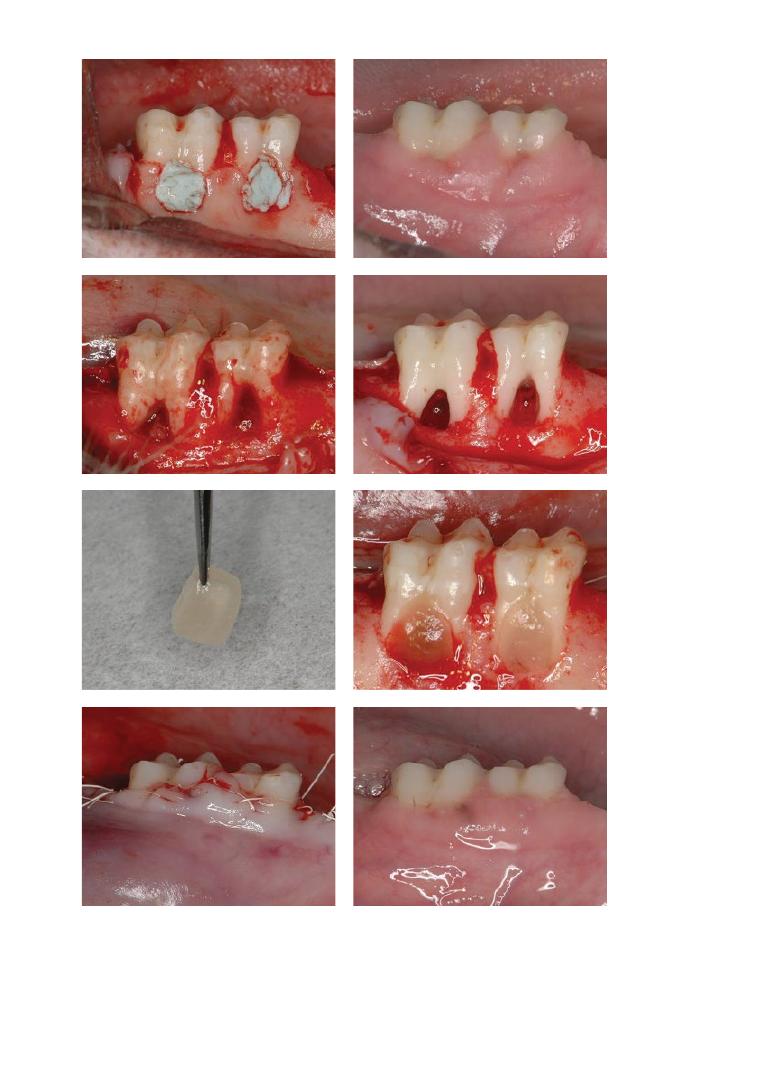

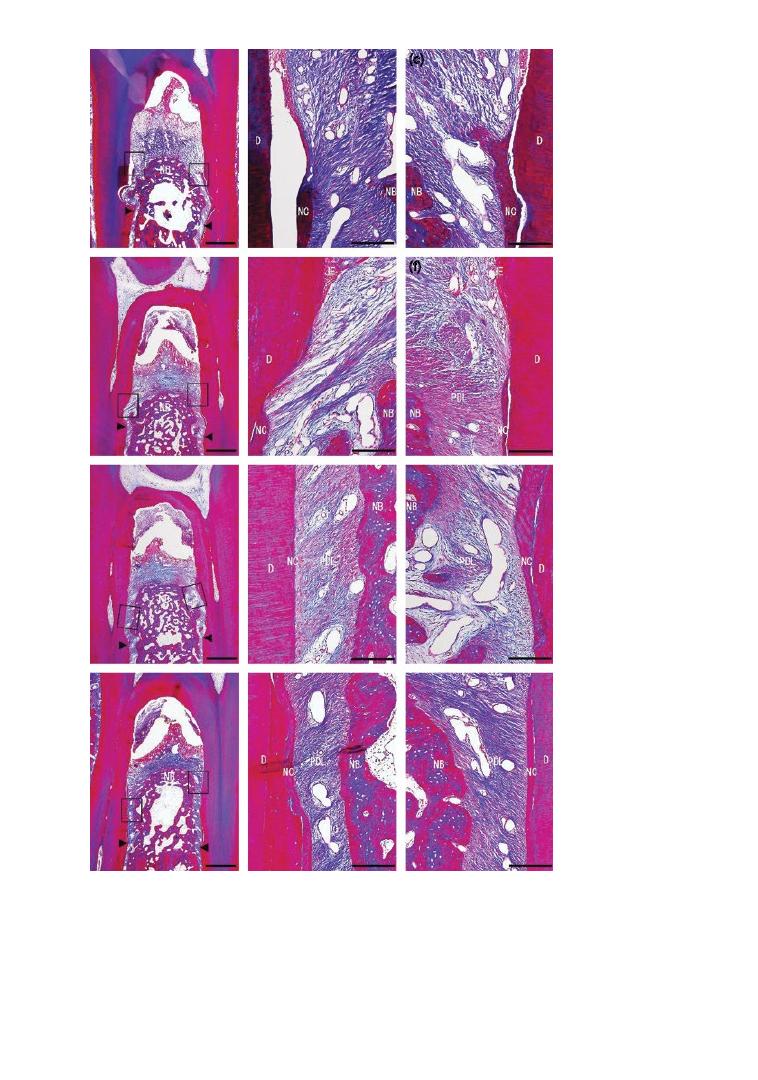

6 Regenerative Therapy of Furcation Involvements in

Preclinical Models: What is Feasible?

105

Nikolaos Donos, Iro Palaska, Elena Calciolari, Yoshinori Shirakata, and Anton Sculean

7 Regenerative Therapy of Furcations in Human Clinical Studies: What has been Achieved

So Far?

137

Søren Jepsen and Karin Jepsen

8 Furcation Therapy: Resective Approach and Restorative Options

161

Roberto Rotundo and Alberto Fonzar

9

Furcation Tunnelling

177

Stefan G. Rüdiger

10 Innovative and Adjunctive Furcation Therapy: Evidence of Success

and Future Perspective

191

Luigi Nibali and Elena Calciolari

Contents

Contents

vi

11 Furcation: Why Bother? Treat the Tooth or Extract and Place an Implant?

209

Nikos Mardas and Stephen Barter

12 Is it Worth it? Health Economics of Furcation Involvement

229

Falk Schwendicke and Christian Graetz

13 Deep Gaps between the Roots of the Molars: A Patient’s Point of View

249

Luigi Nibali

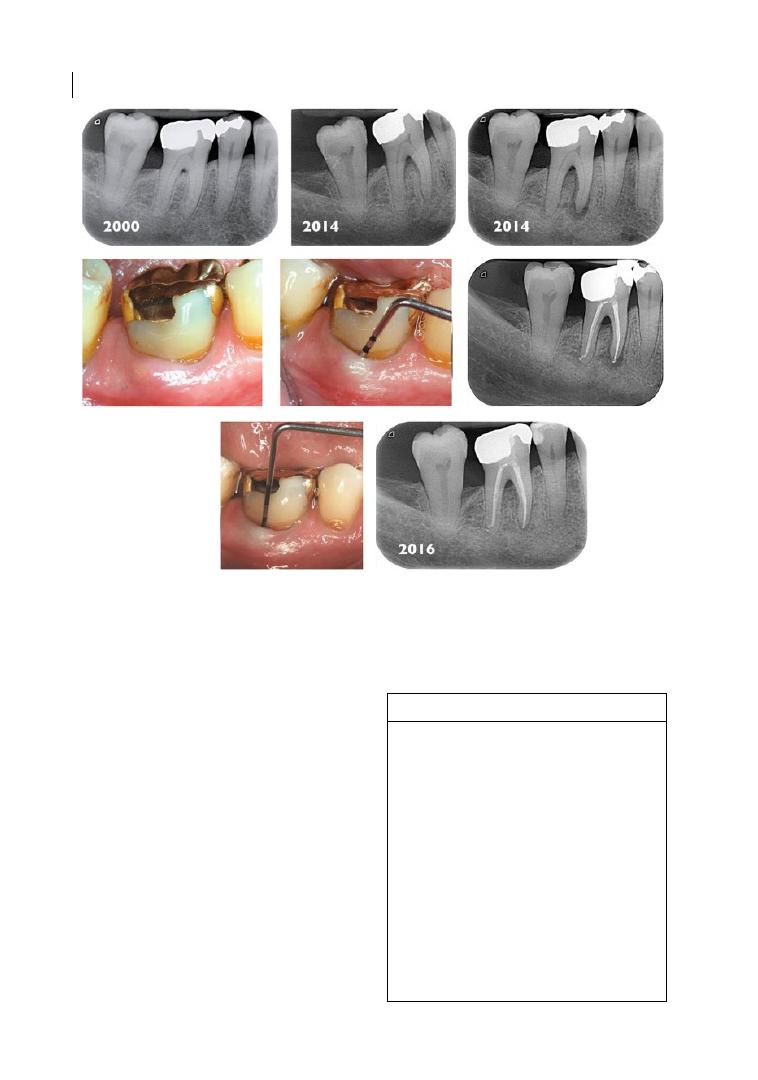

14 Assessment of Two Example Cases Based on a Review of the Literature

257

Luigi Nibali

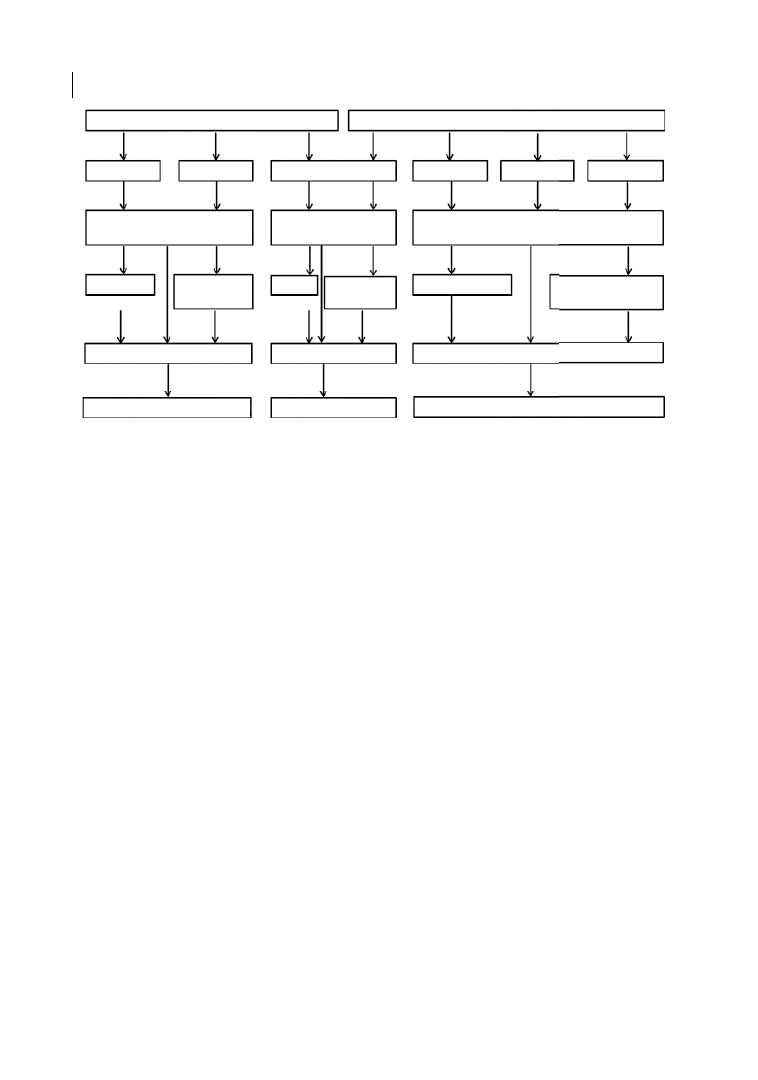

15 Furcations: A Treatment Algorithm

269

Luigi Nibali

Index

285

Chapter No.: 1 Title Name: <TITLENAME>

fbetw.indd

Comp. by: <USER> Date: 14 May 2018 Time: 04:18:26 PM Stage: <STAGE> WorkFlow:

<WORKFLOW>

Page Number: vii

vii

Dr Stephen Barter

Private practice, Eastbourne, UK

Dr Elena Calciolari

Centre for Immunobiology and Regenerative

Medicine

Centre for Oral Clinical Research

Institute of Dentistry

Barts and the London School of Medicine

and Dentistry

Queen Mary University of London (QMUL)

London, UK

Prof. Nikolaos Donos

Centre for Immunobiology and Regenerative

Medicine

Centre for Oral Clinical Research

Institute of Dentistry

Barts and the London School of Medicine

and Dentistry

Queen Mary University of London (QMUL)

London, UK

Prof. Peter Eickholz

Poliklinik für Parodontologie

Zentrum der Zahn‐ Mund‐ und

Kieferheilkunde (Carolinum)

Johann Wolfgang Goethe‐Universität

Frankfurt

Frankfurt am Main

Germany

Dr Federica Fonzar

Private practice

Udine

Italy

Dr Alberto Fonzar

Private practice

Udine

Italy

Dr Riccardo Fabian Fonzar

Private practice

Udine

Italy

Dr Jia‐Hui Fu

Discipline of Periodontics

Faculty of Dentistry

National University of Singapore

Singapore

Dr Christian Graetz

Clinic for Conservative Dentistry and

Periodontology

Christian‐Albrechts‐University

Kiel

Germany

Dr Karin Jepsen

Department of Periodontology

Operative and Preventive Dentistry

University of Bonn

Germany

Prof. Søren Jepsen

Department of Periodontology

Operative and Preventive Dentistry

University of Bonn

Germany

Dr Nikos Mardas

Centre for Immunobiology and Regenerative

Medicine

Centre for Oral Clinical Research

Institute of Dentistry

Barts and the London School of Medicine

and Dentistry

Queen Mary University of London (QMUL)

London

UK

List of Contributors

List of Contributors

viii

Dr Luigi Nibali

Centre for Immunobiology and Regenerative

Medicine

Centre for Oral Clinical Research

Institute of Dentistry

Barts and the London School of Medicine

and Dentistry

Queen Mary University of London (QMUL)

London

UK

Dr Iro Palaska

Centre for Immunobiology and Regenerative

Medicine

Centre for Oral Clinical Research

Institute of Dentistry

Barts and the London School of Medicine

and Dentistry

Queen Mary University of London (QMUL)

London

UK

Dr Bernadette Pretzl

Section of Periodontology

Department of Operative Dentistry

University Clinic Heidelberg

Heidelberg

Germany

Dr Roberto Rotundo

Periodontology Unit

UCL Eastman Dental Institute

London

UK

Dr Stefan G. Rüdiger

Department of Periodontology

Public Dental Service/Malmö University

Malmö

Sweden

Dr Falk Schwendicke

Department of Operative and Preventive

Dentistry

Charité‐Universitätsmedizin Berlin

Berlin

Germany

Prof. Anton Sculean

Department of Periodontology

School of Dental Medicine

University of Bern

Bern

Switzerland

Dr Yoshinori Shirakata

Department of Periodontology

Kagoshima

University Graduate School of Medical and

Dental Sciences

Kagoshima

Japan

Prof. Clemens Walter

Klinik für Parodontologie

Endodontologie und Kariologie

Universitätszahnkliniken,

Universitäres Zentrum für

Zahnmedizin Basel

Basel

Switzerland

Prof. Hom‐Lay Wang

Department of Periodontics and Oral

Medicine

School of Dentistry

University of Michigan

Ann Arbor

MI

USA

Chapter No.: 1 Title Name: <TITLENAME>

fbetw.indd

Comp. by: <USER> Date: 14 May 2018 Time: 04:18:26 PM Stage: <STAGE> WorkFlow:

<WORKFLOW>

Page Number: ix

ix

Foreword

The preservation of tissues and structures

that support the dentition is a major goal of

conservative dentistry for the benefit of our

patients. As dental practitioners, we are

trained to maintain and restore function,

aesthetics, and phonetics for the promotion

of oral health. In the development of this

book, Diagnosis and Treatment of Furcation‐

Involved Teeth, Luigi Nibali and his

co‐authors have assembled an excellent text

that comprehensively examines the manage-

ment of the most challenging‐to‐treat teeth

in the jaws – the molar and premolar teeth

with furcation involvement. It is clear that

clinicians are continually tested on which are

the best approaches to handle these clinical

scenarios that include furcated teeth. The

education, skill, and training required to

manage furcations are significant given the

anatomy, location, and functional biome-

chanical occlusal forces associated with

posterior teeth that make for complex clinical

decision‐making.

In this text, Dr Nibali has convened inter-

national experts providing chapters ranging

from the diagnosis of disease to clinical out-

comes from the health policy expert’s, cari-

ologist’s, periodontist’s, and endodontist’s

perspectives on periodontal‐endodontic‐

restorative dilemmas in patient care. It is

important to recognize that there is a large

evidence base that was initiated from the

‘pre–dental implant era’ on the long‐term

success in the maintenance of compromised

teeth affected by extensive restorative care,

periodontal involvement, and/or pulpal

pathology. This text not only focuses on

diagnosis and treatment, but includes valua-

ble information from a health economics and

treatment algorithms perspectives on long‐

term tooth preservation.

In the first part of the book, a thorough

background on the unique anatomy of multi‐

rooted teeth and corresponding diagnostic,

prognostic, and therapeutic intricacies is

presented. The next section provides a strong

rationale regarding the concept of tooth

preservation from the restorative, periodon-

tal, and endodontic perspectives, which

highlights the strong evidence base of

treatment success of tooth furcations. This

background is important to examine criti-

cally, since many oral implantologists in the

field are not adequately versed on the ramifi-

cations of premature tooth removal versus

those teeth that can be predictably retained

for the long‐term success of the patient. The

application in clinical practice by those with-

out adequate training occasionally errs on

the expedience of tooth extraction, without

pausing to weigh methodically the advan-

tages and disadvantages of embarking on

comprehensive therapy for furcated teeth.

Those without access to this text on the many

options available to increase the lifespan of

molar and premolar teeth may not be pre-

pared to treatment plan the complex dental

patient appropriately for the comprehensive

assessment of restorative, periodontal, endo-

dontic, functional, and aesthetic needs.

Given practice trends of more common

extractions of furcated periodontally and

endodontically compromised teeth, it sug-

gests that ‘the time is right’ to emphasize the

orreorr

x

great potential available in the proper assess-

ment and treatment of furcated teeth. This

section highlights the long‐term success with

proper therapy in maintaining furcated teeth.

The next part of the text highlights the many

different therapeutic modalities that are clini-

cally available to treat multi‐rooted teeth,

including non‐surgical maintenance, resective

procedures (including tunnelling, root resec-

tion, and bicuspidization), and reconstructive

regenerative therapy using biologics or bioma-

terials. Other chapters in the book build on

our existing evidence base to examine the

cases that can genuinely be retained versus

those teeth too compromised as ‘hopeless’

that may benefit from extraction, implant site

development (bone grafting and alveolar ridge

preservation), followed by dental implant

reconstruction. Indeed, dental implant ther-

apy has revolutionized oral care and clinical

treatment decision‐making paradigms for

advanced reconstructive procedures. It is also

crucial for the advanced clinician to under-

stand when and when not to attempt to retain

advanced disease cases. Large epidemiologi-

cal studies have demonstrated that dental

implant therapy is not a ‘panacea’ and that,

given the significant incidence and prevalence

of peri‐implant biological complications in

the molar regions, we should re‐examine the

opportunities for maintaining and treating

furcated teeth more diligently and more fully.

The concluding chapters scrutinize the health

economics opportunities at the patient and

clinician levels in terms of tooth preservation

of furcated molars, and in which types of cases

which treatment planning approach is indi-

cated for such advanced clinical scenarios.

Stimulated by the comprehensive approach

in this book, this can be a renaissance period

in reconstructive dentistry when we firmly

consider the many options available to us as

clinicians to better preserve the dentition in

treating furcation‐involved teeth. This text

lays out a contemporary and exciting oppor-

tunity for us as clinicians to provide our

patients with state‐of‐the‐art therapy for the

betterment of oral health!

William V. Giannobile, DDS, MS, DMedSc

Najjar Endowed Professor of Dentistry &

Biomedical Engineering

Departments of Periodontics and Oral

Medicine & Biomedical Engineering,

University of Michigan School of Dentistry and

College of Engineering, Ann Arbor, MI, USA

Chapter No.: 1 Title Name: <TITLENAME>

fpref.indd

Comp. by: <USER> Date: 14 May 2018 Time: 04:18:30 PM Stage: <STAGE> WorkFlow:

<WORKFLOW>

Page Number: xi

xi

Declare the past, diagnose the present,

foretell the future.

Hippocrates

Doubt is not a pleasant condition, but

certainty is an absurd one.

Voltaire

Young and new to a periodontal clinic, I

remember looking at cases of extensive peri-

odontal and bone loss in multi‐rooted teeth

and wondering how the problem could be

solved, and if and how the tooth could be

retained. The fascination with the spaces

created by inter‐radicular bone resorption,

called ‘furcations’, and the struggle over how

to manage them in the clinic, continues to

occupy large parts of my days and has

prompted me to write this book. Here, with

the help of several expert colleagues, I have

tried to:

●

Critically appraise the evidence.

●

Present expert opinions.

●

Show treated cases.

●

Present useful clinical guidelines, step‐by

step procedures, and treatment algorithms.

The emphasis of the book is to try and

maintain molars affected by furcation involve-

ment and regenerate the lost support, when

possible, accepting that this is not always pos-

sible in the long term. It goes without saying

that primary prevention of periodontitis

remains the best way to prevent tooth loss.

I hope that periodontists, dental/postgraduate

students, hygienists, and

general dentists

might find this book useful for the treatment

of molars already affected by periodontitis

and furcation involvement.

Immense thanks go to all the expert collab-

orators and friends, Will Giannobile,

Bernadette Pretzl, Peter Eickholz, Clemens

Walter, Jia‐Hui Fu, Hom‐Lay Wang, Federica,

Riccardo, and Alberto Fonzar, Roberto

Rotundo, Stefan Rüdiger, Nikos Donos, Toni

Sculean, Elena Calciolari, Iro Palaska,

Yoshinori Shirakata, Søren and Karin Jepsen,

Nikos Mardas, Steve Barter, Christian Graetz,

and Falk Schwendicke, who all contributed

chapters to this book, and to Paul Kletz for

kindly proofreading some of the chapters and

for his support throughout my career. Special

thanks go to the patients who over the years

have been a big source of inspiration with

their interest and commitment, and who

every day make me want to be a better perio-

dontist. I also need to thank my teachers at the

University of Catania and at the UCL Eastman

Dental Institute, who have all contributed,

some with small and some with larger

ingredients, to the cauldron of periodontal

knowledge from which I drew for the plan-

ning and editing of this book. The students

and staff at Barts and the London School of

Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary

University of London (QMUL), are gratefully

acknowledged. But most of all, I would like to

thank my family, Daniela, Domenico, Lorenzo,

Delia, and my parents and in‐laws, for their

continued support of my work.

Luigi Nibali

Preface

Chapter No.: 1 Title Name: <TITLENAME>

flast.indd

Comp. by: <USER> Date: 14 May 2018 Time: 04:18:33 PM Stage: <STAGE> WorkFlow:

<WORKFLOW>

Page Number: xiii

xiii

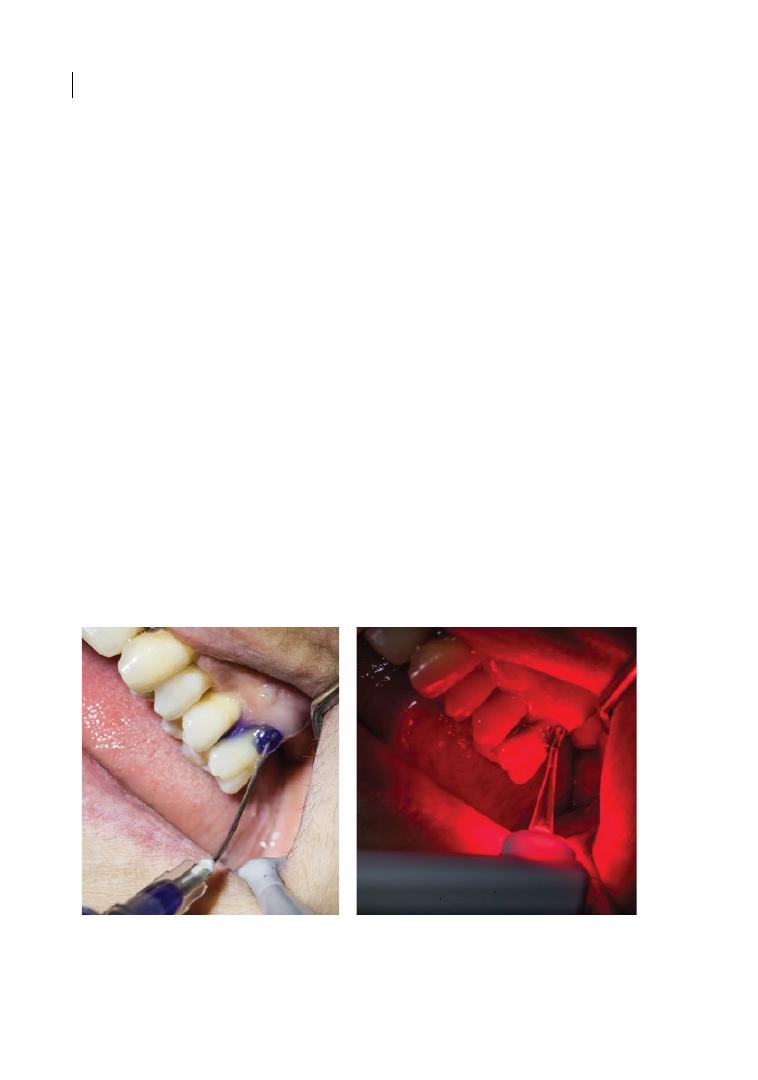

Don’t forget to visit the companion website for this book:

www.wiley.com/go/nibali/diagnosis

There you will find valuable material designed to enhance your learning, including:

●

video clips

●

additional treated cases

Scan this QR code to visit the companion website

About the Companion Website

Diagnosis and Treatment of Furcation-Involved Teeth, First Edition. Edited by Luigi Nibali.

© 2018 John Wiley & Sons Ltd. Published 2018 by John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Companion website: www.wiley.com/go/nibali/diagnosis

Chapter No.: 1 Title Name: <TITLENAME>

c01.indd

Comp. by: <USER> Date: 14 May 2018 Time: 04:18:39 PM Stage: <STAGE> WorkFlow:

<WORKFLOW>

Page Number: 1

1

1.1 Introduction: Why

Focus on Molars?

Dentists generally agree on three statements

about molars:

●

They play an important role in the

dentition.

●

They are difficult to reach for self‐performed

as well as professional cleaning due to their

posterior position in the mouth.

●

They pose some challenges due to their

unique anatomy.

The important role of molar teeth in the den-

tition mainly consists in their contribution to

mastication, because they carry a considera-

ble part of the occlusal load. Hiiemäe (1967)

focused on the masticatory function in mam-

mals and molars grinding the food, and in

1975 Bates et al. reviewed the literature on

the masticatory cycle in natural and artificial

dentitions of men, attributing a fundamental

role to our posterior teeth regarding the

intake and preparation of nutrition. Thus, a

focus on molars and the endeavour to retain

our posterior teeth in a healthy functional

state seems justified.

This chapter will reveal how the posterior

position of molars makes them less accessi-

ble for cleaning, whether it may be self‐

performed or carried out by a dental

professional. This fact, combined with the

unique anatomy of molars, poses a challenge

for all dentists focusing on molar retention.

1.2 The ‘Special’ Anatomy

of Molar Teeth

The essential knowledge of molar root anat-

omy for every periodontist is stressed in a

review by Al‐Shammari et al. (2001). Due to

the higher mortality and compromised

diagnoses of furcation‐involved molars, and

likewise to the reduced efficacy of perio-

dontal therapy in multi‐rooted teeth, the

authors suggest a thorough engagement

with possibly decisive tooth factors such as

furcation entrance area, (bi)furcation

ridges, root surface area, root separation,

and root trunk length, because they may

critically affect the diagnosis and therapy

of multi‐rooted teeth (Leknes 1997; Al‐

Shammari et al. 2001).

For centuries, scientists have concerned

themselves with the human teeth, their anat-

omy, evolution, function, histology, and

histogenesis. Almost 3000 years ago, the

Etruscans populating the northern and cen-

tral part of what is now Italy from 900 to 100

bc recognized the importance of teeth and

fabricated quite delicate dental prostheses,

which Loevy and Kowitz (1997) compared to

prostheses from the mid‐twentieth century.

Chapter 1

Anatomy of Multi‐rooted Teeth and Aetiopathogenesis

of the Furcation Defect

Bernadette Pretzl

Section of Periodontology, Department of Operative Dentistry, University Clinic Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany

Chapter 1

2

The formation and genesis of teeth have

been studied in more detail during the last

three and a half centuries, starting with the

works of the so‐called father of microscopic

anatomy and histology, Marcello Malpighi

(1628–1694) from Italy (Rifkin and

Ackerman 2011), who referred to an ‘invo-

lucrum externum’ describing the outer part

of the tooth, which is today known as

enamel. More than a century later the

formation of cementum (1798–1801) and

dentine (1835–1839) was described (e.g.

Blake 1801; Bell 1835). Written in 1935,

Meyer’s Normal Histology and Histogenesis

of the Human Teeth and Associated Parts

(Churchill 1935) builds the foundation of

our understanding regarding the anatomy

of teeth. Orban and Mueller (1929), who

studied the development of furcations in

multi‐rooted teeth, set a focus on molars

using graphic reconstructions as early as

1929. Their three‐dimensional illustrations

allow a detailed impression of the root area

comparable to those documented by

Svärdström and Wennström (1988). In later

years, scientists focused more and more on

micro‐anatomical and histological research.

Based on the knowledge thus created, the

sequence of molar development can be

divided into three phases analogous to the

development of all teeth (Thesleff and

Hurmerinta 1981): initiation, morphogene-

sis, and cell differentiation. The evolution of

more than one root sets molars apart from

the rest of the dentition: in multi‐rooted

teeth the enamel organ expands with

projections of Hertwig’s root sheath (an epi-

thelial diaphragm). These expansions were

described as lobular growing inwards

between the lobes. Depending on the num-

ber of lobes, two to three (in rarer cases four)

roots develop as soon as the projections have

fused (Bhussry 1980). In an investigation by

Bower (1983) of furcation development,

evolving mandibular molars from 13 foetuses

between 17 and 38 weeks of gestation were

fixed, sectioned, and stained, giving a unique

and detailed impression of furcation devel-

opment. The author measured the base of

the dental papilla as well as the buccal and

lingual epithelial elements and described the

development as follows: The first epithelial

elements, which later evolve into the bifurca-

tion, appear at the 24‐week stage of gesta-

tional age. At that time, the crown formation

of the molar is not complete and Hertwig’s

root sheath has not developed yet (Bhussry

1980; Bower 1983). Thus, the author suggests

that the epithelial elements form extensions

of the epithelium of the developing crown

rather than the root (Bower 1983).

Additionally, he detected stellate reticulum

(which is essential for the formation of

ameloblasts) in the furcation area. The

author speculated about a possible mecha-

nism of enamel formation due to the presence

of stellate reticulum in the region of the

furcation, which develops into ameloblasts,

for example resulting in cervical projections

of enamel.

1.3 Anatomical Factors

in Molar Teeth

In 1988, Svärdström and Wennström plotted

three‐dimensional contour maps in order to

describe the topography of the furcation area

and compared drawings of maxillary and

mandibular molars. These show a complex

area with small ridges, peaks, and pits, and

the authors summarize that the complexity

of the furcation topography evidently

increases the difficulties with respect to

proper debridement once the periodontal

pocket reaches the furcation entrance and

runs into the furcation area. Thus, in addi-

tion to the aforementioned potentially deci-

sive factors – furcation entrance area,

bifurcation ridges, root surface area, and

root trunk length – it has to be kept in mind

that the complexity of the furcation area

itself poses a challenge to the dental practi-

tioner (Svärdström and Wennström 1988).

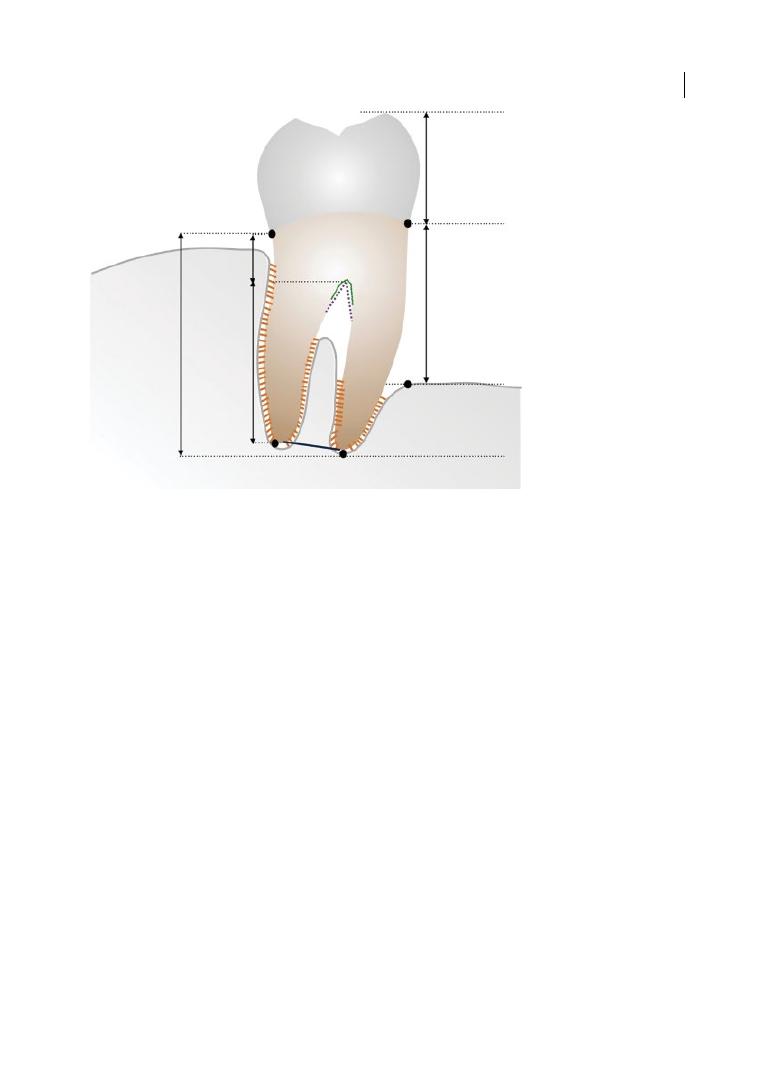

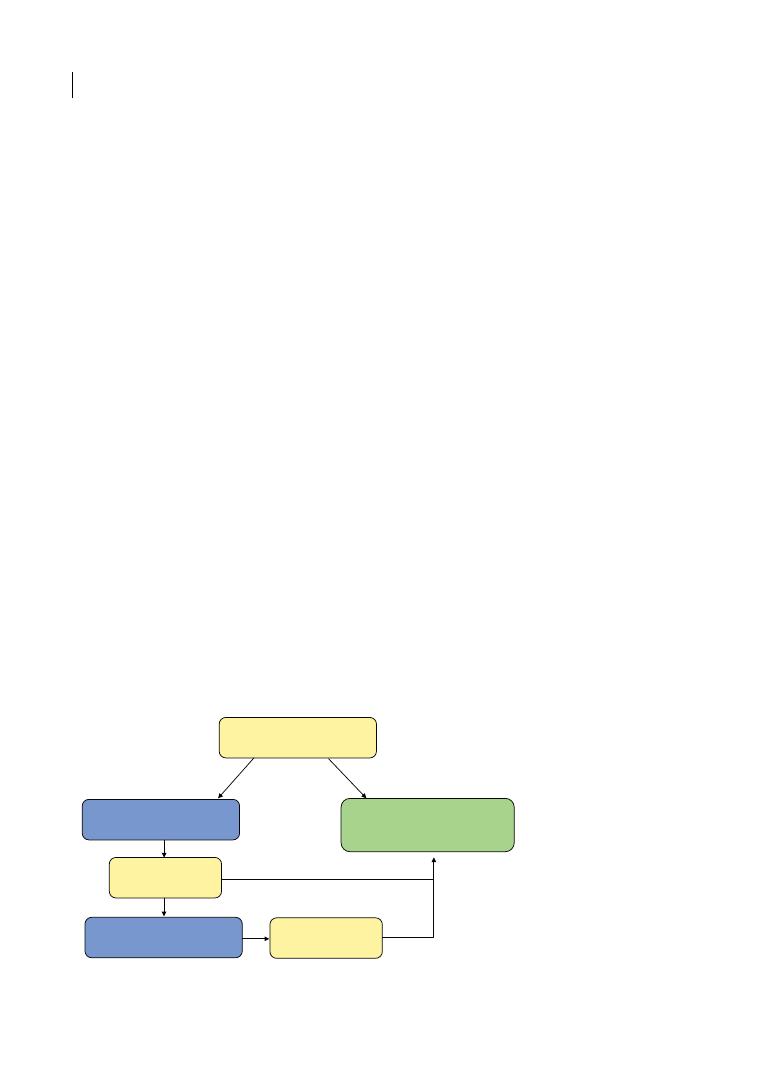

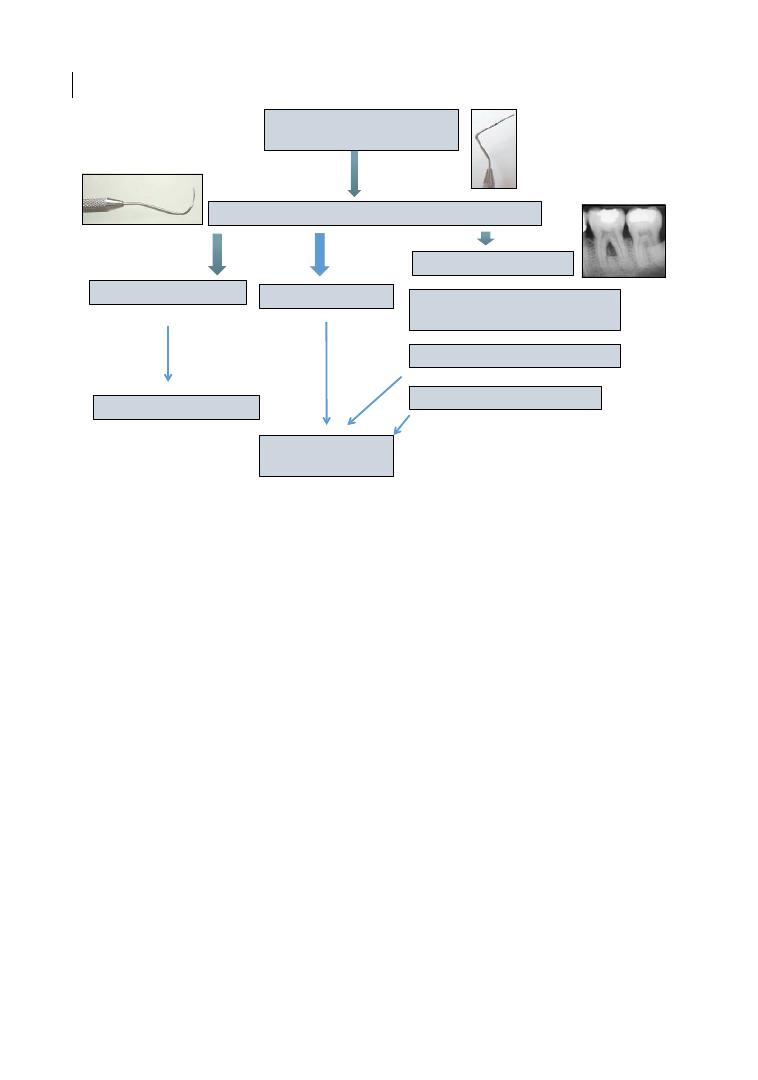

Figure 1.1 shows a diagram of a mandibular

molar, highlighting the main anatomical

features.

Anatomy of Multi-rooted Teeth 3

1.3.1 Furcation Entrance Area

The furcation entrance area was measured

by Bower (1979a) in 114 maxillary and 103

mandibular first molars. The diameter of

the entrance area was smaller than a curette

blade in more than 50% of the examined fur-

cations, with the smallest average diameter

in buccal (b) sites of maxillary as well as

mandibular first molars. No correlation

between the size of the tooth and its furca-

tion entrance area could be detected (Bower

1979a). Hou et al. (1994) studied 89

extracted maxillary and 93 extracted man-

dibular first and second molars microscopi-

cally. In their Chinese population sample,

they concurred with the results presented

by Bower (1979a) in the maxilla and found a

larger diameter in mesio‐ (mp) and disto‐

palatal (dp) furcation entrances for first and

second molars (mp: 1.04 mm and 0.90 mm;

dp: 0.99 mm and 0.67 mm; b: 0.74 mm and

0.63 mm, respectively), which was con-

firmed by Svärdström and Wennström

(1988) and dos Santos et al. (2009).

In mandibular molars the results differed,

with wider entrance areas in buccal furca-

tions of first and second molars (b: 0.88 mm

and 0.73 mm; l: 0.81 mm and 0.71 mm,

respectively). Nonetheless, the furcation

entrance area was < 1 mm in the majority of

molars and < 0.75 mm in 58%, 49%, and 52%

of molars, respectively (Bower 1979a; Chiu

et al. 1991; Hou et al. 1994). Thus, the stand-

ard width of curettes (0.75–1.0 mm) is

mostly too large to access, let alone properly

clean, a furcation entrance. Hou et al. (1994)

concluded that in order to achieve complete

debridement of root surfaces within furca-

tions, an appropriate selection and combi-

nation of ultrasonic tips (diameter 0.56 mm)

and periodontal curettes should be consid-

ered. A recent study by dos Santos et al.

Fornix

Divergence

Root trunk

Root complex

Root cone

Crown

Bone loss

Degree of

separation

Figure 1.1

Drawing of mandibular molar with furcation involvement, showing the main anatomical features,

including root trunk (part of the root from the cemento‐enamel junction [CEJ] to the furcation entrance)

and root cones, and pointing at root divergence and degree of separation between roots. The ‘bone loss’ is

schematically indicated as the distance between the CEJ and the most apical part of the bone. Source:

Courtesy of Dr Aliye Akcali.

Chapter 1

4

(2009) analysed 50 maxillary and 50 man-

dibular molars and confirmed the afore-

mentioned findings, concluding that some

molar furcation entrances could not be

adequately instrumented with curettes and

suggesting the use of alternative hand

instruments. In a review, Matthews and

Tabesh (2004) stressed the importance of

the diameter of the furcation entrance in

order to judge the effect of professional

cleaning, and thus the probable success of

periodontal therapy. The challenges of fur-

cation cleaning are discussed by Fu and

Wang in Chapter 3.

1.3.2 (Bi)furcation Ridges

In early morphological studies of extracted

first molar teeth, cementum was found in the

furcation area in a ridge, building the furca-

tion region in mandibular molars, and was

called an intermediate bifurcation ridge

(IBR), with a high presence of cementum

adjacent to the furcation entrance (Everett

et al. 1958; Bower 1979a, b; see Figure 1.2).

In a study on developing first mandibular

molars sectioned at different gestational

ages, the lingual element was found to be

wider in a mesio‐distal dimension comparable

to studies in extracted molars (Bower 1983,

1979b). Secondly, the exclusion of ectomes-

enchyme between the lobes described by

Bhussry (1980) may explain the large quanti-

ties of cementum in the furcation area of the

mature tooth corresponding to bifurcation

ridges (Bower 1983). In general, two types of

bifurcation ridge are known: one in the

bucco‐lingual direction, the other in the

mesio‐distal direction (intermediate = IBR).

Everett et al. (1958) detected buccal and lin-

gual ridges, mainly constituting of dentine, in

63% of mandibular first molars and IBRs,

mainly composed of cementum, in 73%. The

findings of Burch and Hulen (1974), Dunlap

and Gher (1985), and Hou and Tsai (1997a)

concur, with a prevalence of 76.3%, 70%, and

67.9%, respectively, in mandibular first

molars.

Gher and Vernino (1980) suggest a connec-

tion between the presence of an IBR and the

progression of the furcation defect due to the

morphology and location of IBRs. Hou and

Tsai (1997a) confirmed this correlation.

Additionally, they stated that an even higher

significant correlation exists between the

simultaneous presence of IBRs combined

with cemento‐enamel projections and furca-

tion involvement (FI).

Figure 1.2

Furcation ridge. Source: Courtesy of Dr Nicola Perrini.

Anatomy of Multi-rooted Teeth 5

1.3.3 Root Surface Area

A team of researchers (Hermann et al. 1983;

Dunlap and Gher 1985; Gher and Dunlap

1985) focused on the topic of root surface

area (RSA) in maxillary and mandibular first

molars. In a meta‐analysis derived of data

from 22 original articles, Hujoel (1994) com-

puted a total RSA (corresponding to the

periodontal surface area) for the complete

dentition of 65–86

cm

2

, excluding third

molars. In maxillary first molars a mean of

4.5 cm

2

(second: 4.0 cm

2

) and in mandibular

first molars a mean of 4.2 cm

2

(second:

3.4 cm

2

) were calculated. In molars, it is often

difficult to judge the extent of FI clinically

(Bower 1979b) and thus to determine the

RSA exactly.

1.3.3.1 RSA in the Maxilla

Hermann et al. (1983) as well as Gher and

Dunlap (1985) dissected 20 extracted first

maxillary molars and cross‐sectioned them in

1 mm increments. Molars with fused roots

were excluded. They observed that the disto‐

buccal root had a significantly smaller RSA

than either the mesio‐buccal or palatal root,

confirming the results of Bower (1979b). The

root trunk surface area was significantly larger

than any surface of the three individual roots,

and averaged 32% of the total RSA of the max-

illary first molar (Hermann et al. 1983). Gher

and Dunlap (1985) measured a mean root

length of 13.6 mm (ranging from 10.5 to

16 mm) and a total RSA of 4.77 cm

2

(ranging

from 3.36 to 5.84 cm

2

). Additionally, a ‘bal-

looning’ of the RSA percentage in the furca-

tion area of maxillary molars was described,

which could not be detected in other teeth.

Accordingly, the importance of periodontal

support in the furcation area of maxillary

molars was stressed, concluding that a rela-

tively small attachment gain or loss may have

a significant impact on the stability of the

maxillary first molar (Gher and Dunlap 1985).

1.3.3.2 RSA in the Mandible

For a study on mandibular first molars,

10 teeth were hemisected and measured by

Anderson et al. (1983). They concluded that

the mesial root showed a statistically signifi-

cant greater RSA than the distal root, which

should be taken into consideration when

planning treatment, especially regarding

resective approaches. Dunlap and Gher

(1985) dissected 20 extracted mandibulary

first molars and cross‐sectioned them in

1 mm increments. They too observed that

the distal root had a significantly smaller

RSA than the mesial one, but stressed that

the shapes of the roots (conical for the distal

one; hour‐glass shaped for the mesial one)

should be taken into consideration as well. In

contrast to their findings in the maxilla, the

root trunk surface area was not larger than

the surface of the individual roots, and aver-

aged 30.5% of the total RSA of the mandibu-

lary first molar. They found a mean root

length of 14.4 ± 1.1 mm and a total RSA of

4.37 ± 0.64 cm

2

. In other studies (Jepsen 1963;

Anderson et al. 1983), the total RSA varied

from 4.31 to 4.7 cm

2

.

1.3.4 Root Trunk Length

The portion of multi‐rooted teeth located api-

cal to the cemento‐enamel junction (CEJ) is

called the ‘root complex’ and is divided into

root trunk and root cones. The root trunk is

generally defined as the area of the tooth from

the CEJ to the furcation fornix. In a study by

Gher and Dunlap (1985), the distance between

the CEJ and the furcation entrance in maxil-

lary molars differed considerably between the

mesial (3.6 ± 0.8 mm) and the distal entrance

(4.8 ± 0.8 mm), whereas the buccal entrance

was detected 4.2 ± 1.0 mm apical to the CEJ.

These findings led to the conclusion that the

clinician should suspect a through‐and‐

through furcation (degree III according to

Hamp et al. 1975) in maxillary molars once a

loss of 6 mm in vertical attachment occurred.

In more than 50% of the dissected maxillary

molars, the furcation roof was found coronal

of the root separations and formed a concave

dome between the three roots.

It should be emphasized that the dome‐like

anatomy further complicates therapy and

Chapter 1

6

maintenance of maxillary first molars (Gher

and Dunlap 1985). Hou and Tsai (1997b)

measured the root trunk in 166 extracted

first and second maxillary and 200 extracted

first and second mandibular molars of a

Taiwanese tooth sample. In the maxilla, short

root trunks were more commonly found

buccally, whereas long root trunks were more

commonly found mesially (Hou and Tsai

1997b). The authors found generally longer

root trunks in second molars than in first

molars in both jaws, and additionally stated

that long root trunks are associated with

short root cone length (Hou and Tsai 1997b).

In 134 extracted first and second mandibu-

lar molars, Mandelaris et al. (1998) detected

longer root trunks in lingual molar surfaces

when compared to buccal surfaces (mean:

4.17 mm and 3.14 mm, respectively), confirm-

ing the results of Hou and Tsai (1997b). The

mean distance between the CEJ and the furca-

tion entrance was 4.0 ± 0.7 mm in mandibular

molars (4.6 ± 0.6 mm in maxillary first molars;

Dunlap and Gher 1985; Gher and Dunlap

1985), whereas no root trunk of > 6 mm could

be found (Dunlap and Gher 1985; Mandelaris

et al. 1998). Like in maxillary molars, it can be

concluded that a through‐and‐through furca-

tion (Hamp et al. 1975) should be expected in

the mandible once a loss of 6 mm in vertical

attachment was reached on both sides (buccal

and lingual). On the other hand, it has to be

kept in mind that a furcation defect has a

horizontal component as well. Santana et al.

(2004) measured 100 extracted first and sec-

ond mandibular molars and their findings

suggest that a horizontal attachment loss of

4.3–6.9 mm is essential in order to allow com-

munication between the buccal and lingual

furcation entrance. Complete or partial fusion

of roots is also not unusual in multi‐rooted

teeth. Some 40% of maxillary premolars are

two‐rooted and the entrance to the furcation

is located an average 8 mm from the CEJ, well

into the middle third of the root complex

(Bower 1979a).

A clinically evident FI correlates with the

vertical length and type of the root trunk

(Carnevale 1995; Hou and Tsai 1997b,

Al‐Shammari et al. 2001). Thus, Al‐

Shammari et al. (2001) summarized that the

root trunk length significantly relates to the

prognosis and treatment of molars. A short

root trunk worsens the prognosis with regard

to a more likely FI, but once periodontal

destruction has occurred, it improves the

chances of a successful treatment (Horwitz

et al. 2004).

1.4 Anatomical Aetiological

Factors

1.4.1 Cervical Enamel Projections

Enamel surfaces do not allow for the attach-

ment of connective tissue and represent an

anatomical abnormality in the root area.

Thus, cervical enamel projections (CEP) may

contribute to the development of a furcation

defect (Al‐Shammari et al. 2001). The first to

report a possible connection between CEPs

and periodontal destruction in molars was

Atkinson in 1949. According to Masters and

Hoskins (1964), CEPs can be classified in

three grades (Table 1.1).

Different prevalences of CEPs have been

documented so far. Masters and Hoskins

(1964) found CEPs in 29% of mandibular and

17% of maxillary molars. In Egyptian skulls,

Bissada and Abdelmalek (1973) detected a

CEP prevalence of 8.6%. In the 1138 molars

studied, a higher incidence of CEPs in the

Table 1.1

Classification of cervical enamel

projections.

Grade I

The enamel projection extends from

the cemento‐enamel junction of the

tooth towards the furcation entrance

(<1/3 of the root trunk).

Grade II The enamel projection approaches

the furcation entrance but does not

enter it. No horizontal component is

present (>1/3 of the root trunk).

See Figure 1.3a.

Grade III The enamel projection extends

horizontally into the furcation.

Compare Figures 1.3b and 1.3c.

Anatomy of Multi-rooted Teeth 7

mandible could be confirmed. A study in 200

East Indian skulls with 2000 molars reported a

32.6% incidence rate of CEPs (Swan and Hurt

1976). They were most often reported in man-

dibular second molars (51.0%), followed by

maxillary second molars (45.6%), mandibular

first and maxillary first molars (13.6%). Grade

I enamel projections (Masters and Hoskins

1964) were detected most frequently. These

could not be significantly related to furcation

involvement, as could grade II and III CEPs

(Swan and Hurt 1976). An observation in 78

Taiwanese individuals reported detection of

CEPs in 49.3% of second and 62.3% of first

maxillary and 51.2% of second and 73.9% of

first mandibular molars (Hou and Tsai 1987).

A study by the same authors in furcation‐

involved mandibular molars reported even

higher CEP percentages: 71% of second and

92.9% of first mandibular molars showed

enamel projections (Hou and Tsai 1997b).

Mandelaris et al. (1998) documented CEPs in

66.4% of mandibular molars (61.9% of buccal

and 50.8% of lingual surfaces) ranging from

0.98 to 1.33 mm in diameter. Current research

on CEPs was published in 2013 and 2016.

Bhusari et al. (2013) investigated their inci-

dence on the buccal surface of 944 upper and

lower first, second and third permanent

molars from 89 Indian dry human skulls, and

additionally measured FI. Again, it could be

confirmed that CEPs are found more fre-

quently in the mandible and are significantly

associated with the occurrence of FI. The

incidence ranged from 14.7% in mandibular

second molars to 5.5% in wisdom teeth. The

most recent study was performed using cone‐

beam computed tomography data in a Korean

population analysing 982 mandibular molars

(Lim et al. 2016) and reported an overall

prevalence rate of CEP of 76%. Grade I CEPs

were the most common, followed by CEPs of

grades II and III (Lim et al. 2016).

The huge variations can partly be explained

by different study objects: in human skulls

healthier periodontal conditions can be

assumed, while extracted molars most prob-

ably show worse conditions, and Hou and

Tsai (1987, 1997a) as well as Mandelaris et al.

(1998) studied furcation‐involved molars in

periodontal patients. Additionally, a higher

prevalence of CEPs in Oriental subjects than

in Caucasians is suspected (Hou and Tsai

1987; Lim et al. 2016).

Nonetheless, it can be concluded that CEPs

are a common problem which must be

addressed by clinicians when treating molar

teeth. They are more prevalent than enamel

pearls and prevent connective tissue attach-

ment, thus contributing to the aetiology of

furcation defects, possibly resulting in localized

chronic periodontitis and FI in molars (Leknes

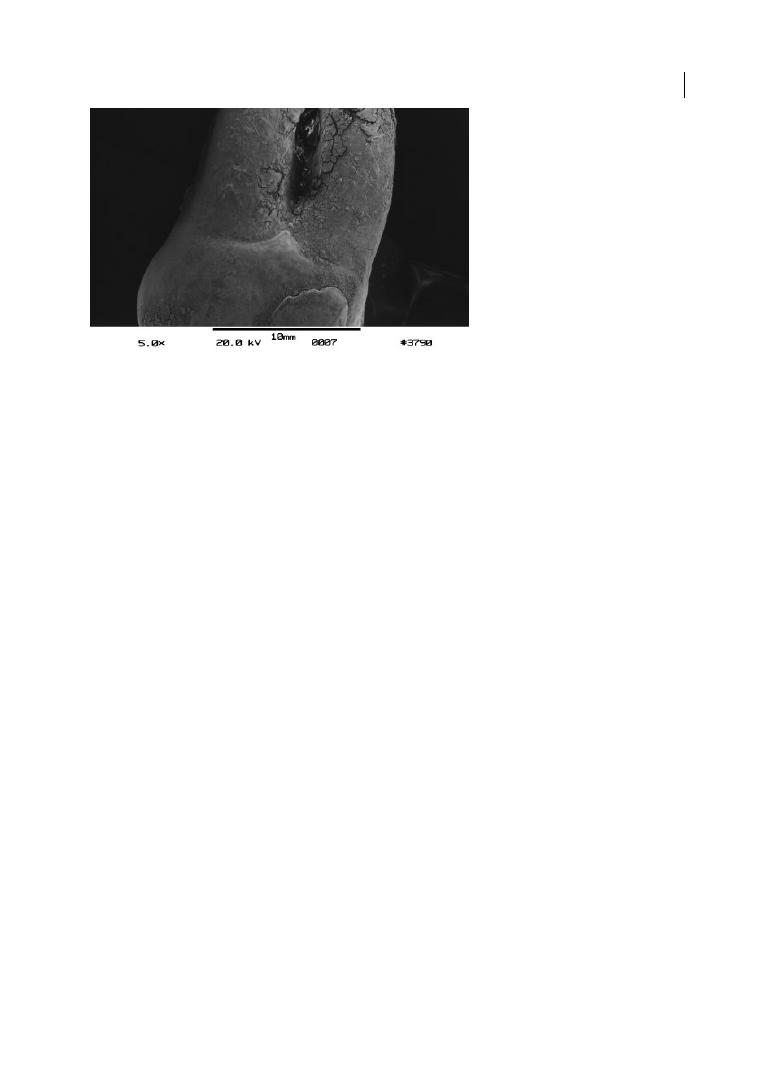

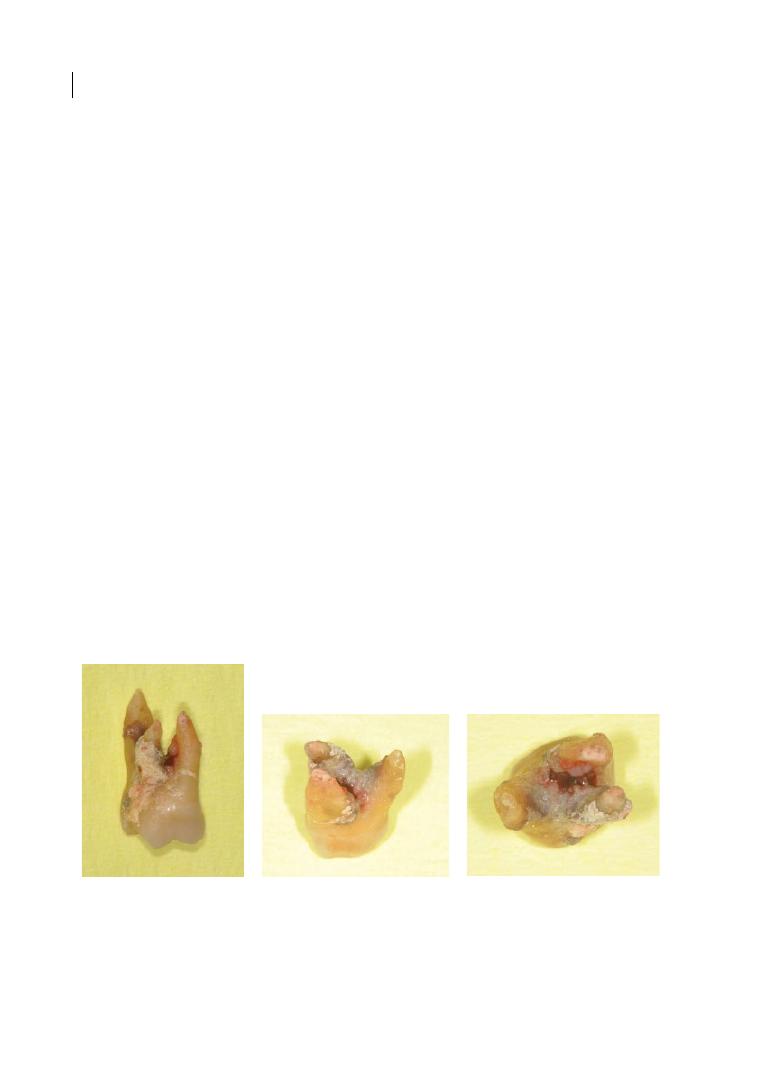

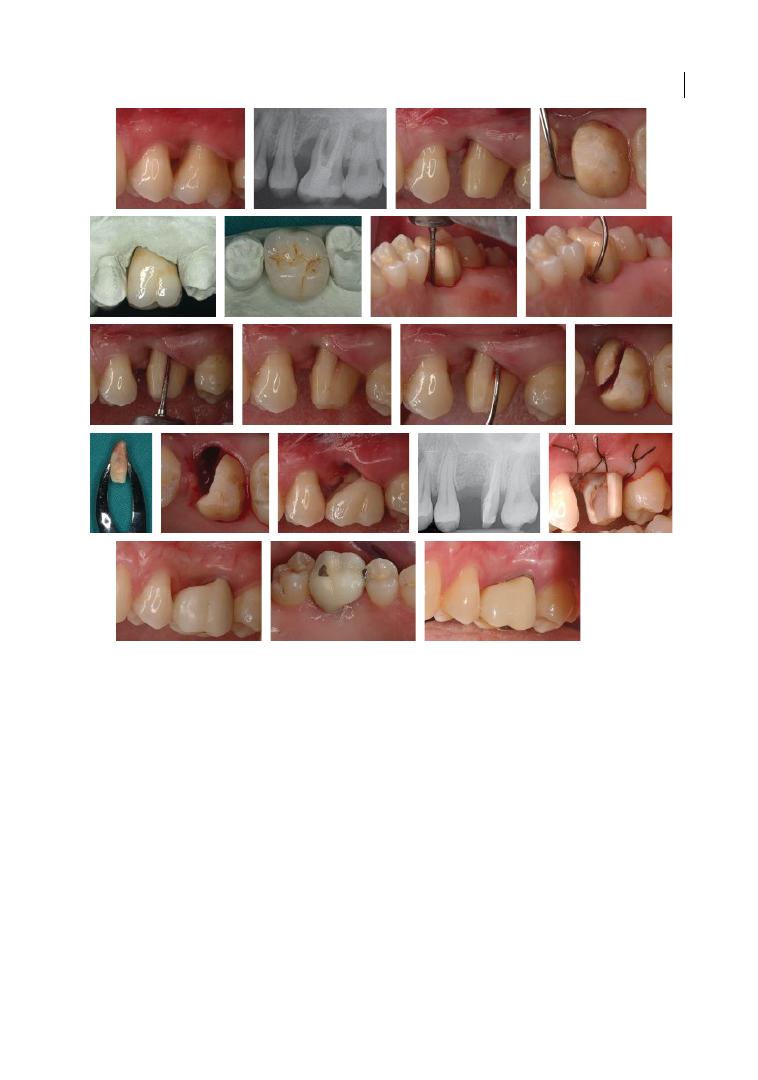

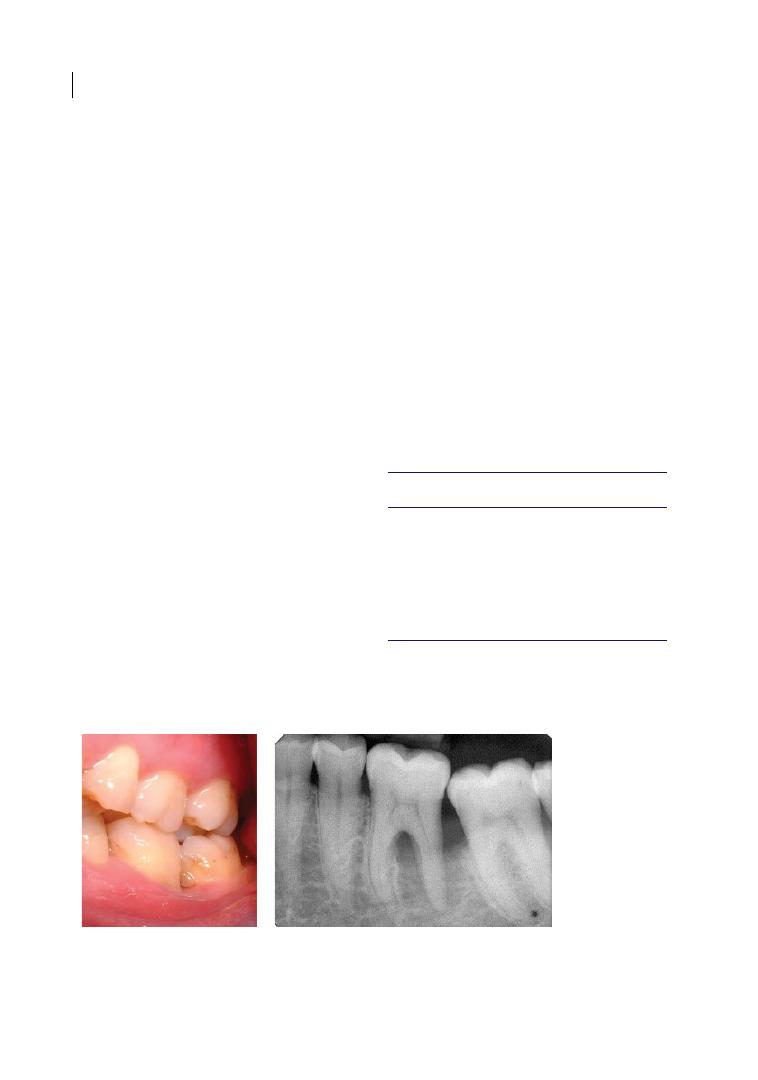

Figure 1.3a

Cervical enamel projection grade II (>1/3 of root trunk; Masters and Hoskins 1964) on upper right

first molar (REM microscope). Source: Eickholz and Hausmann 1998.

Chapter 1

8

1997; Al‐Shammari et al. 2001; Bhusari et al.

2013). Additionally, significantly higher plaque

and gingivitis index values have been reported

in the presence of CEPs (Carnevale et al. 1995).

1.4.2 Enamel Pearls

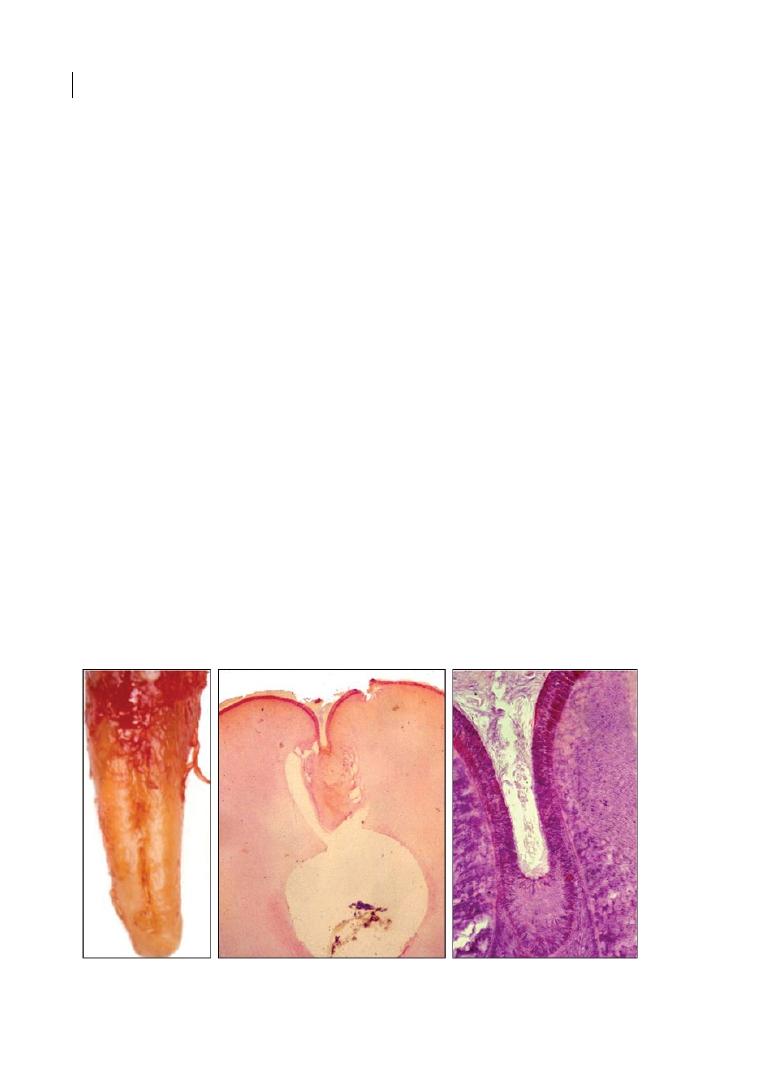

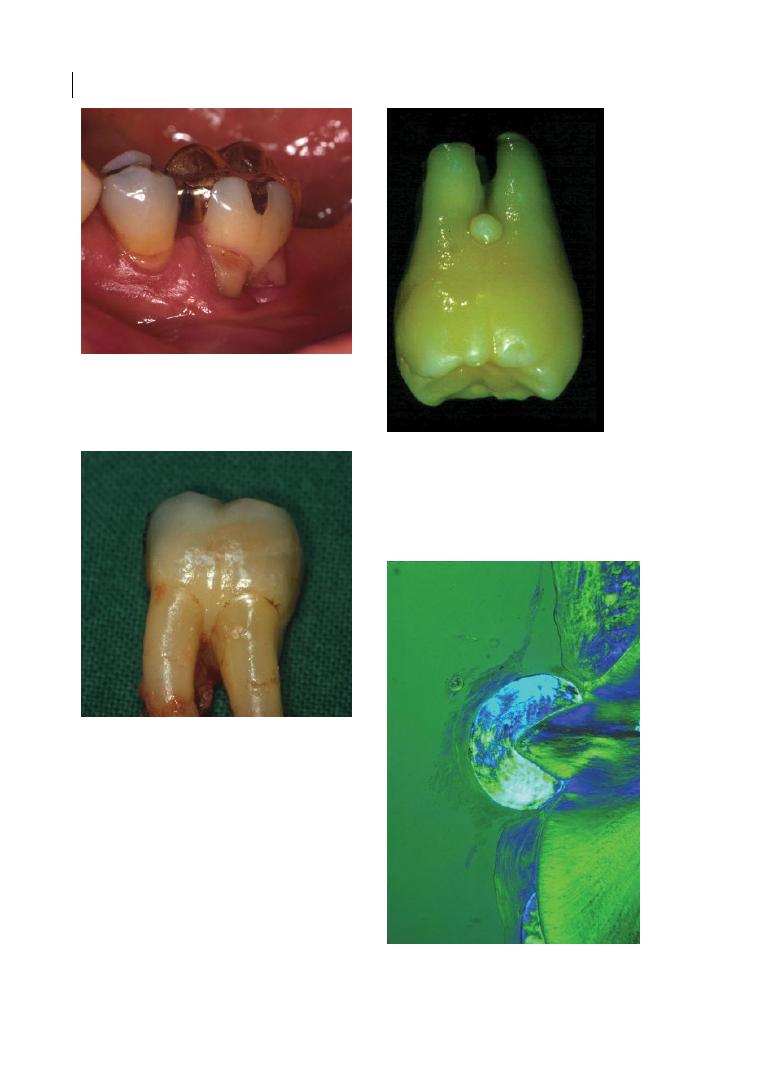

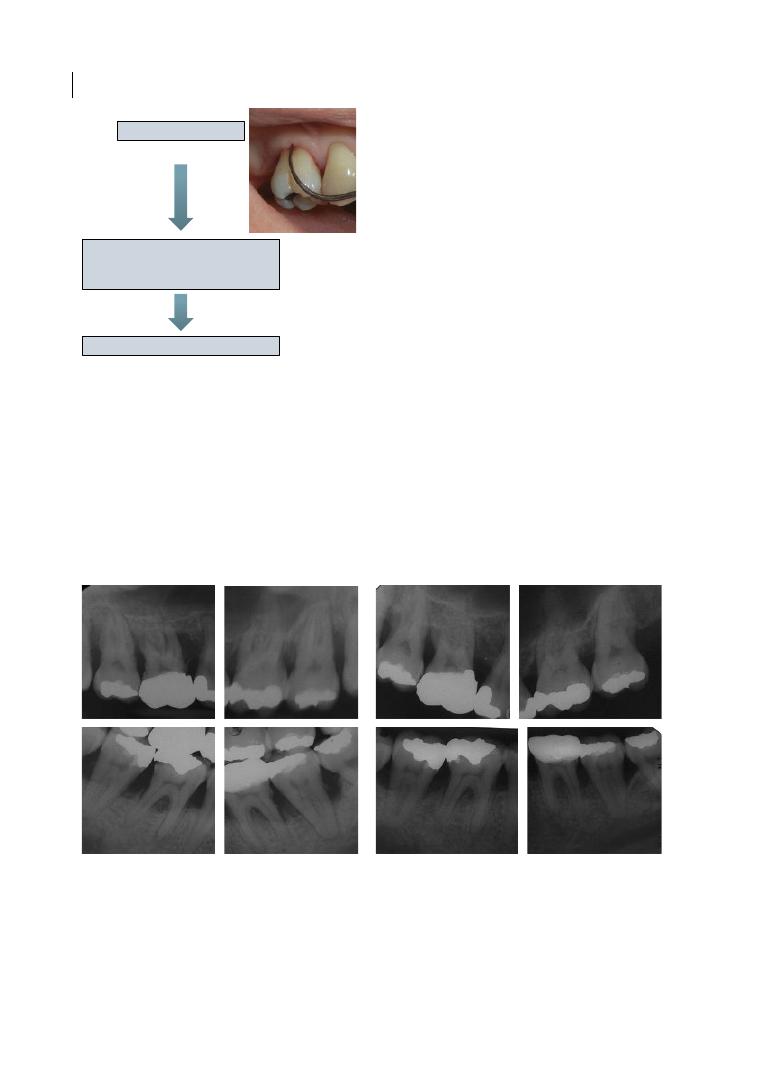

Enamel pearls (see Figure 1.4) were first

described in an article in the American

Journal of Dental Science in 1841 (Moskow

Figure 1.3b

Cervical enamel projection on lower

left first molar; grade III (reaching furcation

entrance area; Masters and Hoskins 1964). Source:

Eickholz 2005.

Figure 1.3c

Cervical enamel projection on extracted

lower right first molar; grade III (reaching furcation

entrance area; Masters and Hoskins 1964). Source:

Eickholz and Hausmann 1998.

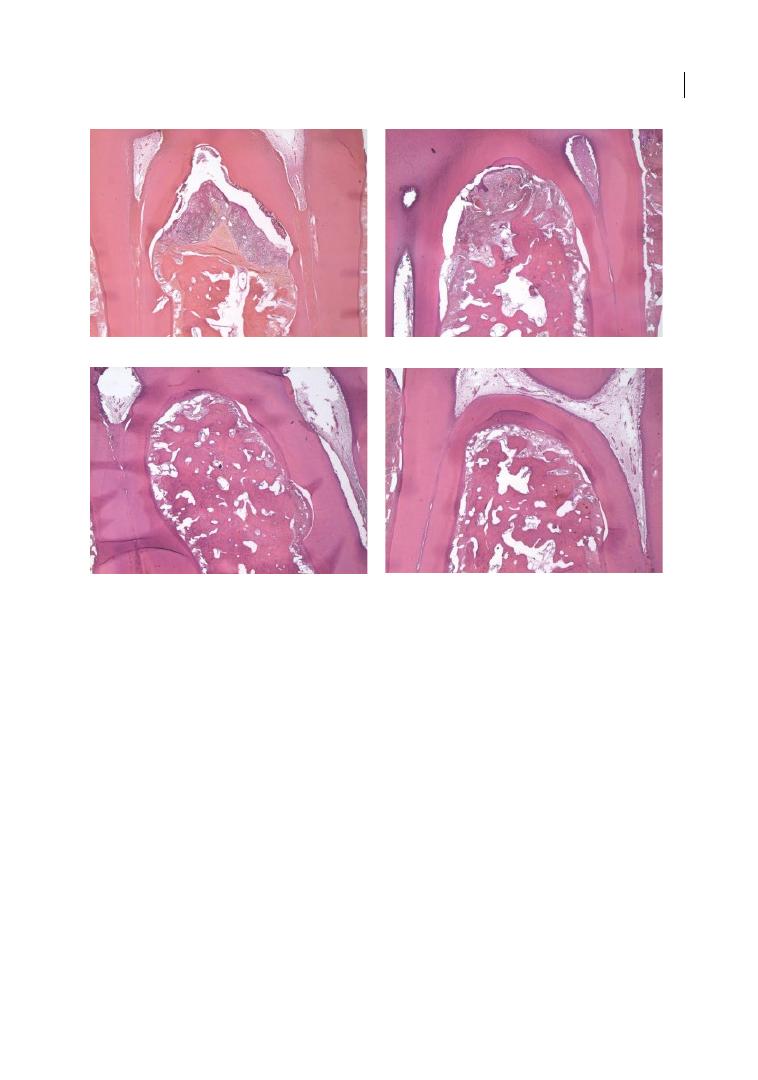

Figure 1.4a

Macroscopic image of an enamel pearl

on an extracted molar. Source: Courtesy of Prof.

Dr. H.-K. Albers.

Figure 1.4b

Microscopic image of an enamel pearl.

Source: Courtesy of Prof. Dr. H.-K. Albers.

Anatomy of Multi-rooted Teeth 9

and Canut 1990). They are ectopic globules

consisting mostly of enamel, often contain-

ing a core of dentine, and they adhere to the

tooth root surface, with a distinct predilec-

tion for the furcation areas of molar teeth,

particularly maxillary third and second

molars. In a review from 1990, an incidence

of 2.6% (ranging from 1.1 to 9.7%) was

reported, with differences among racial

groups and a greater incidence in histological

studies (Moskow and Canut 1990). Like

CEPs, enamel projections prevent connec-

tive tissue attachment and thus contribute to

the aetiology of periodontal destruction.

They usually occur singularly, but up to four

enamel pearls have been observed on the

same tooth (Moskow and Canut 1990).

More recent research demonstrates an

incidence within the range documented by

Moskow and Canut (1990). Darwazeh and

Hamasha (2000) evaluated the presence of

enamel pearls in a Jordanian patient sample,

studying 1032 periapical radiographs. An

incidence of 1.6% of enamel pearls in molars

and 4.76% per subject with no gender differences

was reported. Chrcanovic et al. (2010) evalu-

ated the prevalence of enamel pearls in

45 539 permanent teeth (20 218 molars) from

a human tooth bank in Brazil. They con-

firmed the predominant presence in the

maxilla and reported an incidence of 1.71%

in molars. Akgül et al. (2012) evaluated the

presence of enamel pearls using cone‐beam

computed tomography in 15 185 teeth (4334

molars). An incidence of enamel pearls of

0.83% in molars and 4.69% per subject with no

gender differences was reported. Again, the

incidence was significantly higher in the max-

illa. Colak et al. (2014) studied the prevalence

of enamel pearls in Turkish dental patients

and detected them in 0.85% of teeth and 5.1%

of subjects, with a contradictory higher inci-

dence in the mandible and in male patients.

Although lower in incidence than enamel

projections, it can be summarized that

enamel pearls play an important role in the

aetiology of furcation defects, and it is con-

sidered essential to diagnose enamel pearls

early on to allow for an adequate prognosis of

molar retention and probably alter the thera-

peutic approach.

1.5 Periodontal Aetiological

Factors in Molar Teeth

Aetiological factors interact with the previ-

ously described anatomical factors and may

lead to periodontal destruction and attach-

ment loss in molars, and thus result in a fur-

cation defect. According to Al‐Shammari

et al. (2001), plaque‐associated inflammation,

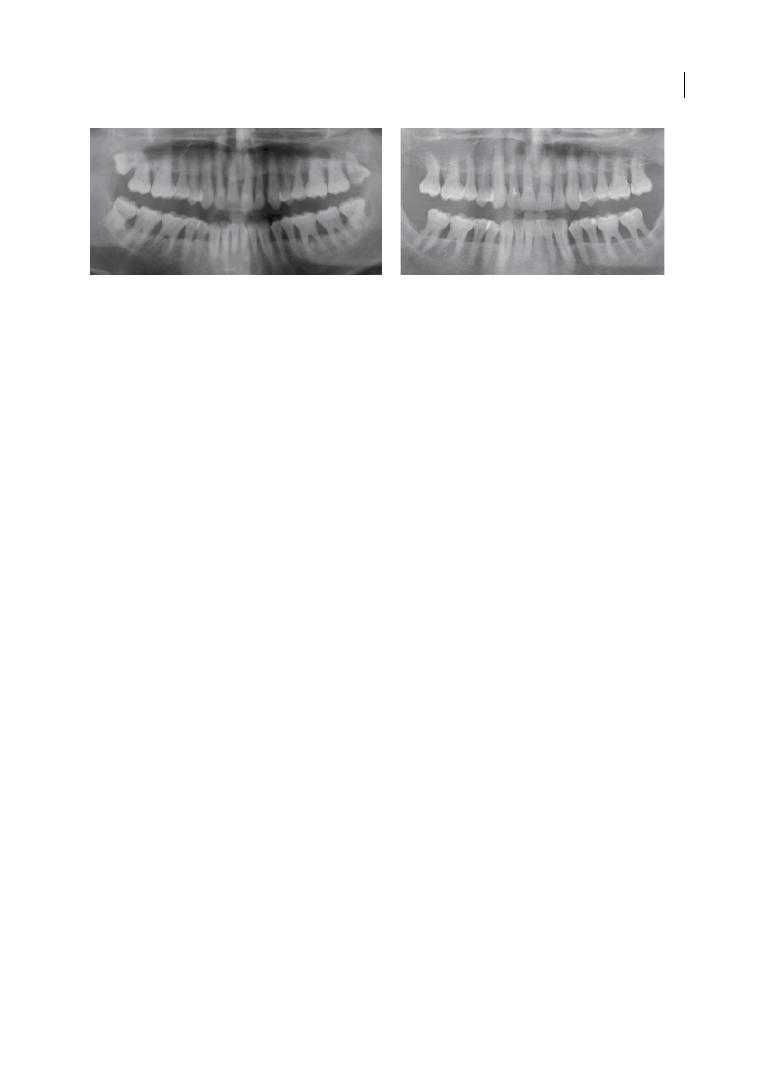

Figure 1.4c

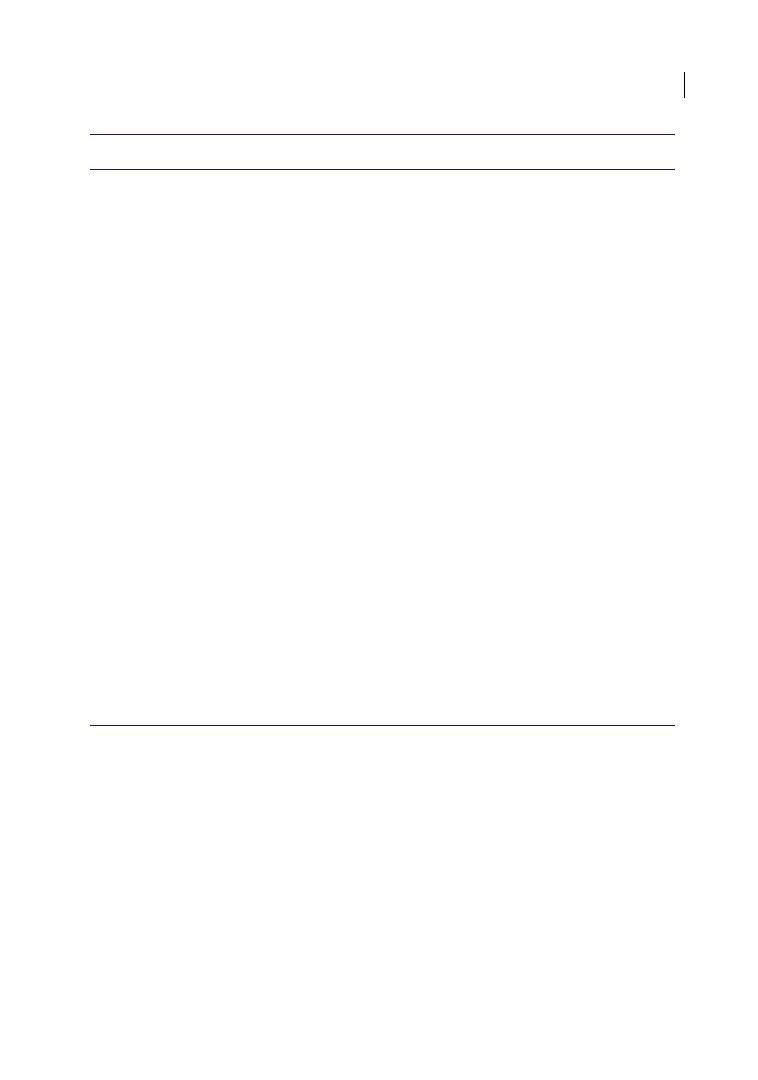

Orthopantomogram showing enamel pearls on upper right and left second molars. Source:

Eickholz and Hausmann 1998.

Chapter 1

10

trauma from occlusion, pulpal pathology,

vertical root fractures, and iatrogenic factors

need to be taken into consideration.

1.5.1 Plaque‐associated

Inflammation

The reader of this book will surely be well

accustomed to plaque formation and the

inflammatory component of gingivitis and

periodontitis. What is special about molars

in this context? In general, it can be stated

that furcations are more prone to plaque

adhesion and less likely to stay plaque free.

The anatomy of the furcation favours reten-

tion of bacterial deposits and renders hygiene

procedures difficult (Matthews and Tabesh

2004). In 1987, Nordland et al. monitored

2472 sites in 19 periodontal patients for

24 months after periodontal therapy, and

reported that furcation sites responded less

favourably to therapy and were more likely to

exhibit higher plaque and gingivitis scores.

Apart from that, it is assumed that furcation

areas are an extension of periodontal pock-

ets, because unique histological features are

lacking (Glickman 1950; Al‐Shammari et al.

2001). Thus, plaque formation follows the

same process in molars and their furcations

as in the remaining dentition (Leknes 1997).

1.5.2 Occlusal Trauma

Trauma from occlusion is suspected to

be another aetiological factor contributing

to periodontal destruction in molars.

Two groups of researchers, Glickman and

co‐workers as well as Lindhe and co‐workers,

focused on this topic in animal studies apply-

ing excessive occlusal forces on molars. In

their classic studies on beagle dogs, Lindhe

and Svanberg (1974) and Nyman et al. (1978)

reported significant alterations in tooth

mobility combined with angular bony defects

and loss of periodontal support in artificially

created, gingivally inflamed multi‐rooted

teeth carrying splints, compared to teeth

with inflammation but carrying no addi-

tional occlusal load. Even before that,

Glickman et al. (1961) compared the effect of

occlusal force on splinted and non‐splinted

teeth in rhesus monkeys, and suggested that

the fibre orientation in the furcation area

makes multi‐rooted teeth more susceptible

to increased functional forces. More recently,

Nakatsu et al. (2014) confirmed the afore-

mentioned findings in an observation in rats.

On the other hand, Waerhaug (1980) con-

cluded from his observations of 46 human

molars (extracted because of advanced peri-

odontal destruction) that increased mobility

and occlusal trauma are not involved in the

aetiology of the FI and are instead a late

symptom of periodontal disease. Thus, the

impact of occlusal forces in the aetiology of

periodontitis in general and FI in particular

remains controversial (Al‐Shammari et al.

2001; Reinhardt and Killeen 2015). In a

review, Harrel (2003) suggest that occlusal

interferences should be regarded as a poten-

tial risk factor comparable to smoking, rather

than a causative or aetiological factor.

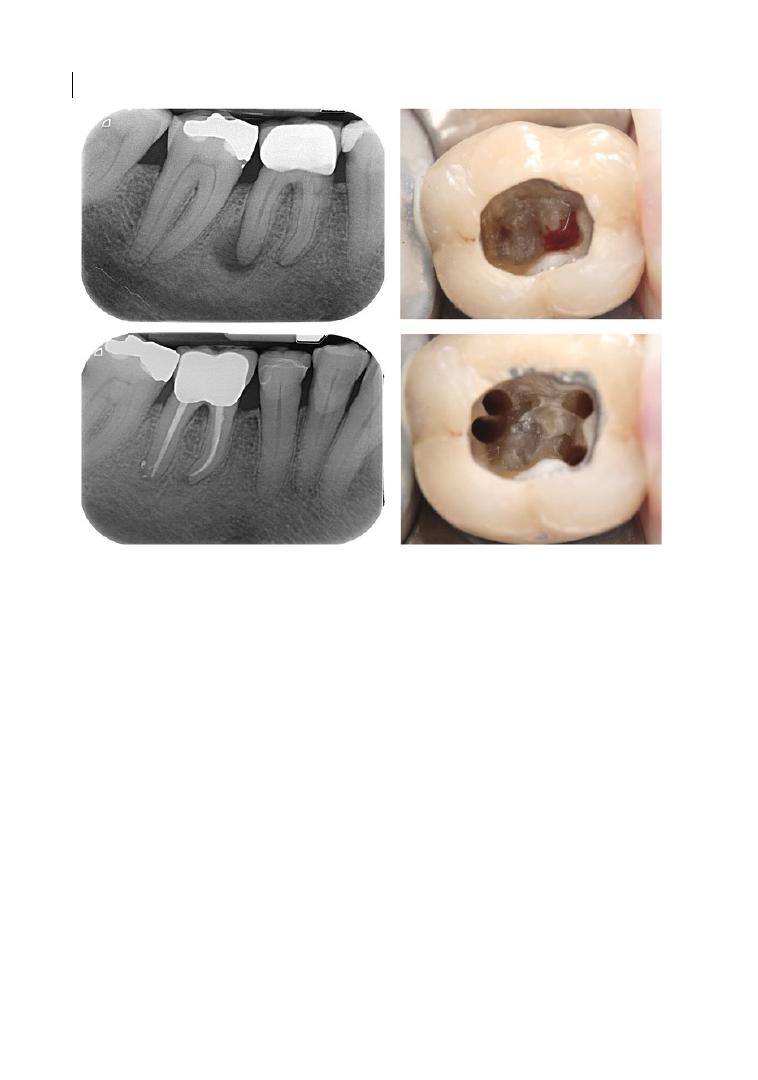

1.5.3 Vertical Root Fractures

It is generally agreed that vertical root frac-

tures, which can occur in a longitudinal

direction on any surface of the root, are dif-

ficult to diagnose because they share symp-

toms with other dental conditions (Matthews

and Tabesh 2004). Additionally, in most cases

mild pain or a dull discomfort is the only

clinical symptom of a vertical root fracture

(Meister at al. 1980). They result in rapid

localized loss of attachment and bone

(Walton et al. 1984) and can lead to FI

depending on their position. Mostly, a poor

prognosis is assigned to teeth exhibiting ver-

tical root fractures (Al‐Shammari et al. 2001;

Matthews and Tabesh 2004).

1.5.4 Endodontic Origin

and Pulpal Pathology

Accessory canals are quite common in molar

teeth. A study of 46 extracted molars of both

Anatomy of Multi-rooted Teeth 11

jaws found accessory canals in 59% of exam-

ined teeth (Lowman et al. 1973). Burch and

Hulen (1974) reported ‘openings’ in 76% of

the furcations of maxillary and mandibular

molars. These canals allow for products of

pulpal necrosis to enter the furcation area

and cause an inflammatory lesion (Carnevale

et al. 1995). Thus, a pulpal pathosis can result

in FI. Carnevale et al. (1995) reported that

proximal and inter‐radicular bone destruc-

tion of endodontic origin is reversible after

root canal treatment. Periodontal therapy

only becomes necessary in the case of a

persistent lesion after the endodontic treat-

ment. A more detailed description of the

associations between FI and endodontic

pathology is provided in Chapter 4.

1.5.5 Iatrogenic Factors

Generally, overhanging dental restorations

or discrepancies of the subgingival margin in

any kind of restoration or even orthodontic

bands allow for adhesion of plaque and show

detrimental effects on adjacent gingival tis-

sues; additionally, the fit of prosthetic resto-

rations is mostly less than perfect (Leknes

1997) and builds a niche, where plaque

formation is facilitated and cleansing diffi-

cult. According to a study by Lang et al.

(1983) in dental students with healthy gingi-

vae who received proximal inlays with 1 mm

overhangs, the microbial composition of the

subgingival biofilm shifted from healthy to a

composition characteristically found in peri-

odontitis. Thus, the authors concluded that

the changes observed in the subgingival

microflora document a potential mechanism

for the initiation of periodontal disease asso-

ciated with iatrogenic factors. Wang et al.

(1993) focused on molars and assessed the

correlation between FI and the presence of a

crown or proximal restoration in 134 perio-

dontal patients during maintenance therapy.

Their results showed a significant associa-

tion between FI as well as periodontal attach-

ment loss and the presence of a crown or

restoration.

Additionally, Matthews and Tabesh (2004)

commented that overhangs not only build a

plaque retention niche, but also impinge on

the biological width (between the depth of a

healthy sulcus and the alveolar crest) and

thus cause damage. They report ranges of

overhangs in restored teeth from 18 to 87%

(Matthews and Tabesh 2004). In general, the

placement of restorative margins subgingi-

vally results in more plaque, more gingival

inflammation and deeper periodontal

pockets.

It can be concluded that special care needs to

be taken when placing restorations, and over-

hangs need to be diagnosed and removed as

early as possible. Should a restoration margin

need to be placed subgingivally, the biological

width has to be kept in mind and crown length-

ening considered. Thus, a dento‐gingival attach-

ment may be achieved (Herrero et al. 1995).

Summary of Evidence

●

Numerous anatomical factors like furca-

tion entrance area, bifurcation ridges,

root surface area, and root trunk length

need to be considered in the diagnosis and

periodontal treatment of molars. The

periodontist should be aware of these fac-

tors because they may have a significant

impact on the prognosis and therapeutic

outcome of multi‐rooted teeth.

●

Iatrogenic factors should be tackled early

on (at the beginning of periodontal ther-

apy), thus allowing for improvement of

gingival and periodontal conditions.

Chapter 1

12

References

Akgül, N., Caglayan, F., Durna, N. et al. (2012).

Evaluation of enamel pearls by cone‐beam

computed tomography (CBCT). Medicina

Oral Patologica Oral y Cirurgia Bucal 17,

e218–e222.

Al‐Shammari, K.F., Kazor, C.E., and Wang,

H.‐L. (2001). Molar root anatomy and

management of furcation defects. Journal of

Clinical Periodontology 28, 730–740.

Anderson, R.W., McGarrah, H.E., Lamb, R.D.,

and Eick, J.D. (1983). Root surface

measurements of mandibular molars using

stereophotogrammetry. Journal of the

American Dental Association 107, 613–615.

Atkinson, S.R. (1949). Changing dynamics of

the growing face. American Journal of

Orthodontics 35, 815–836.

Bates, J.F., Stafford, G.D., and Harrison, A.

(1975). Masticatory function – a review of

the literature: 1. The form of the masticatory

cycle. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation 2 (3),

281–301.

Bell, T. (1835). The Anatomy, Physiology, and

Diseases of the Teeth. London: S. Highley.

Bhusari, P., Sugandhi, A., Belludi, S.A., and

Shoyab Khan, S. (2013). Prevalence of

enamel projections and its co‐relation with

furcation involvement in maxillary and

mandibular molars: A study on dry skull.

Journal of the Indian Society of

Periodontology 17, 601–604.

Bhussry, B.R. (1980). Development and growth

of teeth. In: Orban’s Oral Histology and

Embryology (ed. G.S. Kumar), 23–44. St

Louis, MO: C.V. Mosby.

Bissada, N.F., and Abdelmalek, R.G. (1973).

Incidence of cervical enamel projections and

its relationship to furcation involvement in

Egyptian skulls. Journal of Periodontology

44, 583–585.

Blake, R. (1801). An Essay on the Structure and

Formation of the Teeth in Man and Various

Animals. Dublin: Porter.

Bower, R.C. (1979a). Furcation morphology

relative to periodontal treatment: Furcation

entrance architecture. Journal of

Periodontology 50, 23–27.

Bower, R.C. (1979b). Furcation morphology

relative to periodontal treatment: Furcation

root surface anatomy. Journal of

Periodontology 50, 366–374.

Bower, R.C. (1983). Furcation development of

human mandibular first molar teeth: A

histologic graphic reconstructional study.

Journal of Periodontal Research 18, 412–419.

Burch, J.G., and Hulen, S. (1974). A study of

the presence of accessory foramina and the

topography of molar furcations. Oral

Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology 38,

451–455.

Carnevale, G., Pontoriero, R., and Hürzeler,

M.B. (1995). Management of furcation

involvement. Periodontology 2000 9, 69–89.

Chiu, B.M., Zee, K.Y., Corbet, E.F., and

Holmgren, C.J. (1991). Periodontal

implications of furcation entrance dimensions

in Chinese first permanent molars. Journal

of Periodontology 62, 308–311.

Chrcanovic, B.R., Abreu, M.H.N.G., and

Custódio A.L.N. (2010). Prevalence of

enamel pearls in teeth from a human teeth

bank. Journal of Oral Science 52, 257–260.

Churchill, H.R. (1935). Meyer’s Normal

Histology and Histogenesis of the Human

Teeth and Associated Parts (trans. and ed.

H.R. Churchill). Philadelphia, PA: J.B.

Lippincott.

Çolak, H., Hamidi, M.M., Uzgur, R. et al.

(2014). Radiographic evaluation of the

prevalence of enamel pearls in a sample

adult dental population. European Review

for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences

18, 440–444.

Darwazeh, A., and Hamasha, A.A. (2002).

Radiographic evidence of enamel pearls in

Jordanian dental patients. Oral Surgery, Oral

Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology

Endodontology 89, 255–258.

dos Santos, K.M., Pinto, S.C., Pochapski, M.T.

et al. (2009). Molar furcation entrance and

its relation to the width of curette blades

used in periodontal mechanical therapy.

International Journal of Dental Hygiene 7,

263–269.

Anatomy of Multi-rooted Teeth 13

Dunlap, R.M., and Gher, M.E. (1985). Root

surface measurements of the mandibular

first molar. Journal of Periodontology 56 (4),

234–248.

Eickholz, P. (2005). Clinical and radiographic

diagnosis and epidemiology of furcation

involvement. In: Parodontologie: Praxis der

Zahnheilkunde Band 4 (ed. D. Heidemann),

Chapter 2. Munich: Urban & Fischer/

Elsevier.

Eickholz, P., and Hausmann, E. (1998).

Diagnostik der Furkationsbeteiligung: Eine

Übersicht. Quintessenz 49 (1), 59–67.

Everett, F.G., Jump, E.B., Holder, T.D., and

Williams, G.C. (1958). The intermediate

bifurcational ridge: A study of the

morphology of the bifurcation of the lower

first molar. Journal of Dental Research 37,

162–169.

Gher, M.W. Jr, and Dunlap, R.M. (1985). Linear

variation of the root surface area of the

maxillary first molar. Journal of

Periodontology 56, 39–43.

Gher, M.E., and Vernino, A.R. (1980). Root

morphology: Clinical significance in

pathogenesis and treatment of periodontal

disease. Journal of the American Dental

Association 101, 627–633.

Glickman, I. (1950). Bifurcation involvement

in periodontal disease. Journal of the

American Dental Association 40, 528–538.

Glickman, I., Stein, R.S., and Smulow, J.B.

(1961). The effect of increased functional

forces upon the periodontium of splinted

and non‐splinted teeth. Journal of

Periodontology 32, 290–300.

Hamp, S.‐E., Nyman, S., and Lindhe, J. (1975).

Periodontal treatment of multirooted teeth:

Results after 5 years. Journal of Clinical

Periodontology 2, 126–135.

Harrel, S.K. (2003). Occlusal forces as a risk

factor for periodontal disease.

Periodontology 2000 32, 111–117.

Hermann, D.W., Gher, M.E., Jr, Dunlap, R.M.,

and Pelleu, G.B., Jr (1983). The potential

attachment area of the maxillary first molar.

Journal of Periodontology 54, 431–434.

Herrero, F., Scott, J.B., Maropis, P.S., and

Yukna R.A. (1995). Clinical comparison of

desired versus actual amount of surgical

crown lengthening. Journal of

Periodontology 66, 568–571.

Hiiemäe, K.M. (1967). Masticatory function in

the mammals. Journal of Dental Research

46, 883–893.

Horwitz, J., Machtei, E.E., Reitmeir, P. et al.

(2004). Radiographic parameters as

prognostic indicators for healing of class II

furcation defects. Journal of Clinical

Periodontology 31, 105–111.

Hou, G.L., and Tsai, C.C. (1987).

Relationship between periodontal furcation

involvement and molar cervical enamel

projections. Journal of Periodontology 58,

715–721.

Hou, G.L., and Tsai, C.C. (1997a). Cervical

enamel projections and intermediate

bifurcational ridge correlated with molar

furcation involvements. Journal of

Periodontology 68, 687–693.

Hou, G.L., and Tsai, C.C. (1997b). Types and

dimensions of root trunk correlating with

diagnosis of molar furcation involvements.

Journal of Clinical Periodontology 24,

129–135.

Hou, G.L., Chen, S.F., Wu, Y.M., and Tsai, C.C.

(1994). The topography of the furcation

entrance in Chinese molars: Furcation

entrance dimensions. Journal of Clinical

Periodontology 21, 451–456.

Hujoel, P.P. (1994). A meta‐analysis of normal

ranges for root surface areas of the

permanent dentition. Journal of Clinical

Periodontology 21, 225–229.

Jepsen, A. (1963). Root surface measurement

and a method for x‐ray determination of

root surface area. Acta Odontologica

Scandinavica 21, 35–46.

Lang, N.P., Kiel, R.A., and Anderhalden, K.

(1983). Clinical and microbiological effects

of subgingival restorations with overhanging

or clinically perfect margins. Journal of

Clinical Periodontology 10, 563–578.

Leknes, K.N. (1997). The influence of anatomic

and iatrogenic root surface characteristics

on bacterial colonization and periodontal

destruction: A review. Journal of

Periodontology 68, 507–516.

Chapter 1

14

Lim, H.‐C., Jeon, S.‐K., Cha, J.‐K. et al. (2016).

Prevalence of cervical enamel projection

and its impact on furcation involvement in

mandibular molars: A cone‐beam computed

tomography study in Koreans. The

Anatomical Record 299, 379–384.

Lindhe, J., and Svanberg, G. (1974). Influence

of trauma from occlusion on progression of

experimental periodontitis in the beagle dog.

Journal of Clinical Periodontology 1, 3–14.

Loevy, H.T., and Kowitz, A.A. (1997). The

dawn of dentistry: Dentistry among the

Etruscans. International Dental Journal 47,

279–284.

Lowman, J.V., Burke, R.S., and Pelleu, G.B.

(1973). Patent accessory canals: Incidence in

molar furcation region. Oral Surgery Oral

Medicine Oral Pathology 38, 451–455.

Mandelaris, G.A., Wang, H.L., and MacNeil,

R.L. (1998). A morphometric analysis of the

furcation region of mandibular molars.

Compendium of Continuing Education in

Dentistry 19, 113–120.

Masters, D.H., and Hoskins, S.W. (1964).

Projection of cervical enamel into molar

furcations. Journal of Periodontology 35,

49–53.

Matthews, D., and Tabesh, M. (2004).

Detection of localized tooth‐related factors

that predispose to periodontal infections.

Periodontology 2000 34, 136–150.

Meister, F., Lommel, T.J., and Gerstein, H.

(1980). Diagnosis and possible causes of

vertical root fractures. Oral Surgery, Oral

Medicine, Oral Pathology 49, 243–253.

Moskow, B.S., and Canut, P.M. (1990). Studies

on root enamel. Journal of Clinical

Periodontology 17, 275–281.

Nakatsu, S., Yoshinaga, Y., Kuramoto, A. et al.

(2014). Occlusal trauma accelerates

attachment loss at the onset of experimental

periodontitis in rats. Journal of Periodontal

Research 49, 314–322.

Nordland, P., Garrett, S., Kiger, R.D. et al.

(1987). The effect of plaque control and root

debridement in molar teeth. Journal of

Clinical Periodontology 14, 231–236.

Nyman, S., Lindhe, J., and Ericsson, I. (1978).

The effect of progressive tooth mobility on

destructive periodontitis in the dog. Journal

of Clinical Periodontology 5, 213–225.

Orban, B., and Mueller, E. (1929). The

development of the bifurcation of

multirooted teeth. Journal of the American

Dental Association 16, 297–319.

Reinhardt, R.A., and Killeen, A.C. (2015). Do

mobility and occlusal trauma impact

periodontal longevity? Dental Clinics of

North America 59, 873–883.

Rifkin, B.A., and Ackerman, M.J. (2011).

Human Anatomy: A Visual History from the

Renaissance to the Digital Age. New York,

NY: Abrams Books.

Santana, R.B., Uzel, I.M., Gusman, H. et al.

(2004). Morphometric analysis of the

furcation anatomy of mandibular molars.

Journal of Periodontology 75, 824–829.

Svärdström, G., and Wennström, J.L. (1988).

Furcation topography of the maxillary and

mandibular first molars. Journal of Clinical

Periodontology 15, 271–275.

Swan, R.H., and Hurt, W.C. (1976). Cervical

enamel projections as an etiologic factor in

furcation involvement. Journal of the

American Dental Association 93, 342–345.

Thesleff, I., and Hurmerinta, K. (1981). Tissue

interactions in tooth development.

Differentiation 18, 75–88.

Waerhaug, J. (1980). The furcation problem:

Etiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, therapy

and prognosis. Journal of Clinical

Periodontology 7, 73–95.

Walton, R.E., Michelich, R.J., and Smith, G.N.

(1984). The histopathogenesis of vertical

root fractures. Journal of Endodontics 10,

48–56.

Wang, H.L., Burgett, F.G., and Shyr, Y. (1993).

The relationship between restoration and

furcation involvement on molar teeth.

Journal of Periodontology 64, 302–305.

Diagnosis and Treatment of Furcation-Involved Teeth, First Edition. Edited by Luigi Nibali.

© 2018 John Wiley & Sons Ltd. Published 2018 by John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Companion website: www.wiley.com/go/nibali/diagnosis

Chapter No.: 1 Title Name: <TITLENAME>

c02.indd

Comp. by: <USER> Date: 14 May 2018 Time: 04:18:51 PM Stage: <STAGE> WorkFlow:

<WORKFLOW>

Page Number: 15

15

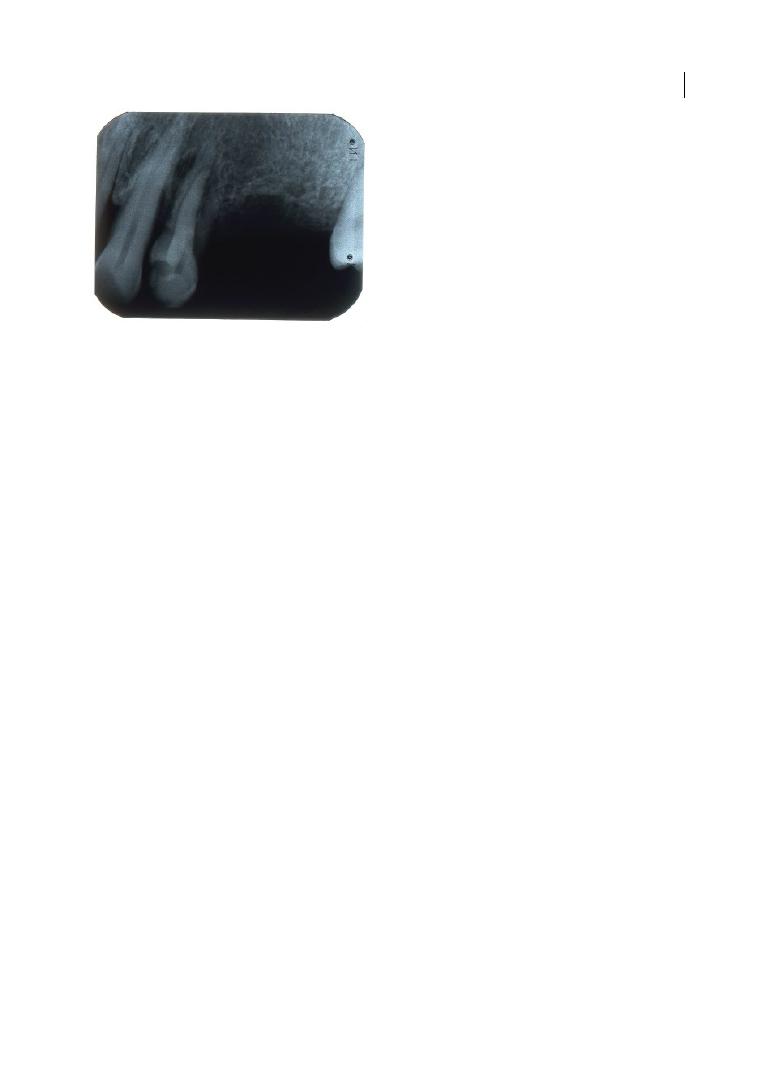

2.1 Introduction

In single‐rooted teeth, periodontal destruc-

tion proceeds from the cemento‐enamel

junction (CEJ) apically, predominantly in a

vertical direction. The vertical attachment

loss is assessed as vertical probing attach-

ment loss (PAL‐V) from the CEJ, or if the CEJ

is destroyed by a restoration from the resto-

ration margin (RM) to the bottom of the per-

iodontal pocket. Vertical bone loss is assessed

radiographically or by vertical probing bone

level (PBL‐V) from the CEJ or RM to the

alveolar crest. If periodontitis affects multi‐

rooted teeth, the tissues are not only

destroyed vertically but also horizontally

between the roots, creating furcation involve-

ment. This dimension of periodontal

destruction (horizontal attachment and bone

loss) may be assessed as horizontal probing

attachment loss (PAL‐H) or horizontal

probing bone level (PBL‐H).

Horizontal probing attachment loss and

bone loss in the furcation area create a niche

(furcation involvement), which impedes

accessibility for individual oral hygiene in the

molar region (Lang et al. 1973) and profes-

sional root debridement (Fleischer et al.

1989). This adds to the factors contributing

to more severe disease progression in

furcation‐involved molars, recurrent perio-

dontal infection, and as a result an inferior

long‐term prognosis of these teeth (McGuire

and Nunn 1996; Dannewitz et al. 2006, 2016;

Pretzl et al. 2008; Salvi et al. 2014; Graetz

et al. 2015). Furcation‐involved molars

respond less favourably to periodontal ther-

apy than molars without furcation involve-

ment or single‐rooted teeth, and are at

greater risk for further attachment loss

(Nordland et al. 1987; Loos et al. 1989; Wang

et al. 1994) than other teeth. Addressing this

issue, Kalkwarf et al. (1988) reported the suc-

cess of different surgical and non‐surgical

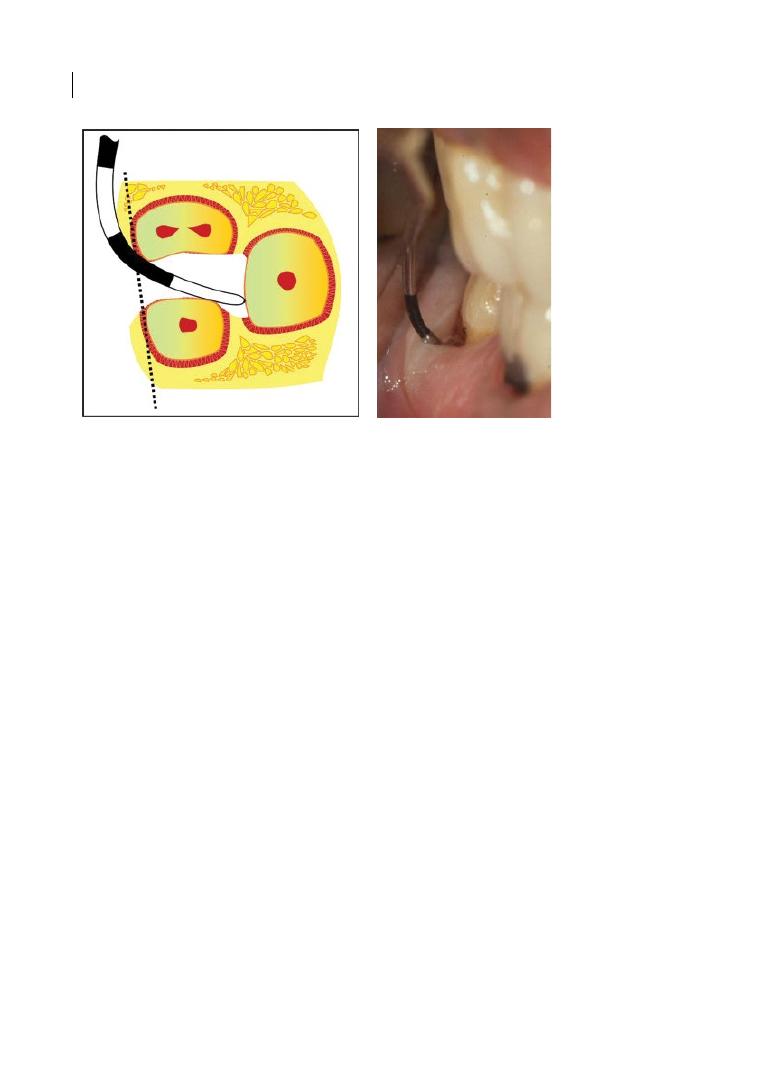

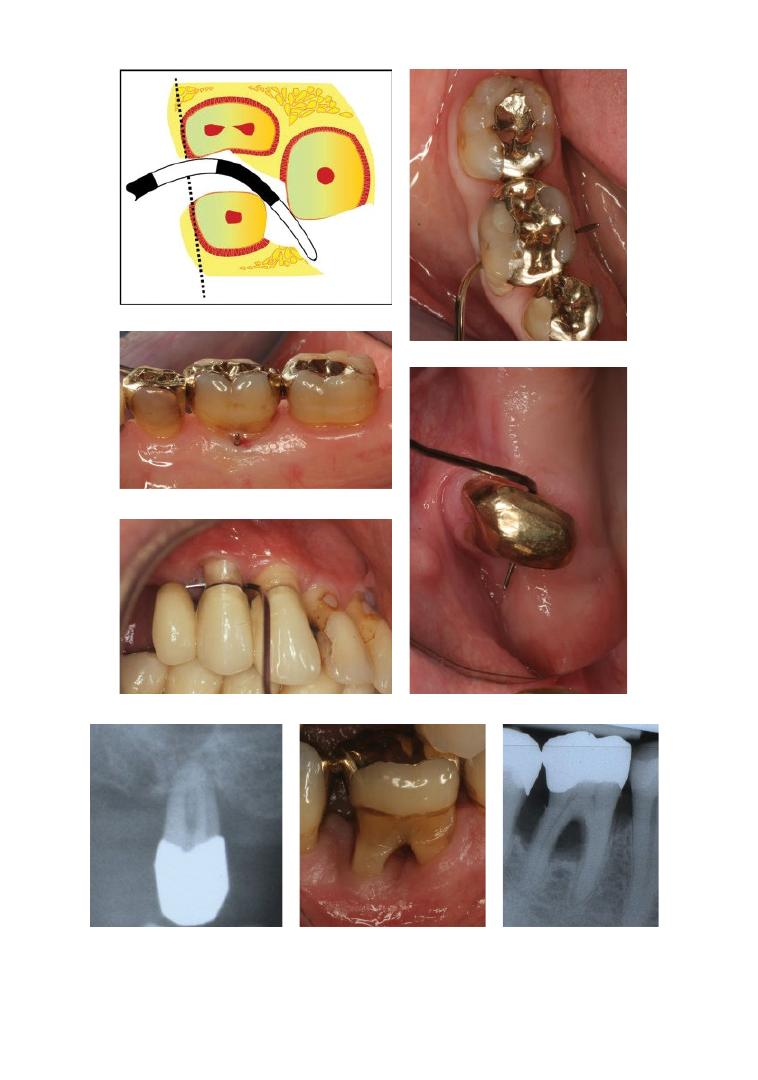

treatment modalities in 158 molars.

Irrespective of the therapy performed, the

horizontal defect in the furcation area

increased during the two‐year follow‐up.

Thus, reliable diagnosis of incidence and

extent of furcation involvement is decisive

for prognosis and treatment planning.

2.2 Clinical Furcation

Diagnosis

Furcation involvement can only be found in

multi‐rooted teeth (Table 2.1). More than

one root is regularly found in maxillary and

mandibular molars as well as in first maxillary

Chapter 2

Clinical and Radiographic Diagnosis and Epidemiology

of Furcation Involvement

Peter Eickholz

1

and Clemens Walter

2

1

Poliklinik für Parodontologie, Zentrum der Zahn‐ Mund‐ und Kieferheilkunde (Carolinum), Johann Wolfgang Goethe‐Universität

Frankfurt, Frankfurt am Main, Germany

2

Klinik für Parodontologie, Endodontologie und Kariologie, Universitätszahnkliniken, Universitäres Zentrum für Zahnmedizin Basel,

Basel, Switzerland

Chapter 2

16

premolars (see Chapter 1). However, two‐

rooted variants may be found in second max-

illary premolars and mandibular anteriors.

Rarely, three‐rooted variants may be found in

mandibular molars and maxillary premolars

(Mohammadi et al. 2013). Those sites at

which furcation entrances are regularly

expected have to be examined for furcation

involvement on a regular basis in the course

of periodontal examination. Search for and

scoring of furcation involvement are funda-

mental elements of periodontal examination.

Particularly in untreated periodontal

patients, furcation entrances do not lie open.

In most cases they are covered by gingiva.

Thus, furcation involvement cannot be seen

simply with the naked eye, but has to be

probed below the gingival margin. The

bizarre anatomy of furcations (Schroeder

and Scherle 1987), their curved course, and

the fact that the furcation entrances of maxil-

lary premolars and molars open into inter-

proximal spaces require the use of particular

curved furcation probes in furcation diagno-

sis (e.g. Nabers probe; Figure 2.1). The probe

is placed onto the tooth surface coronally of

the gingival margin at the site where a furca-

tion entrance is expected (e.g. lingual of a

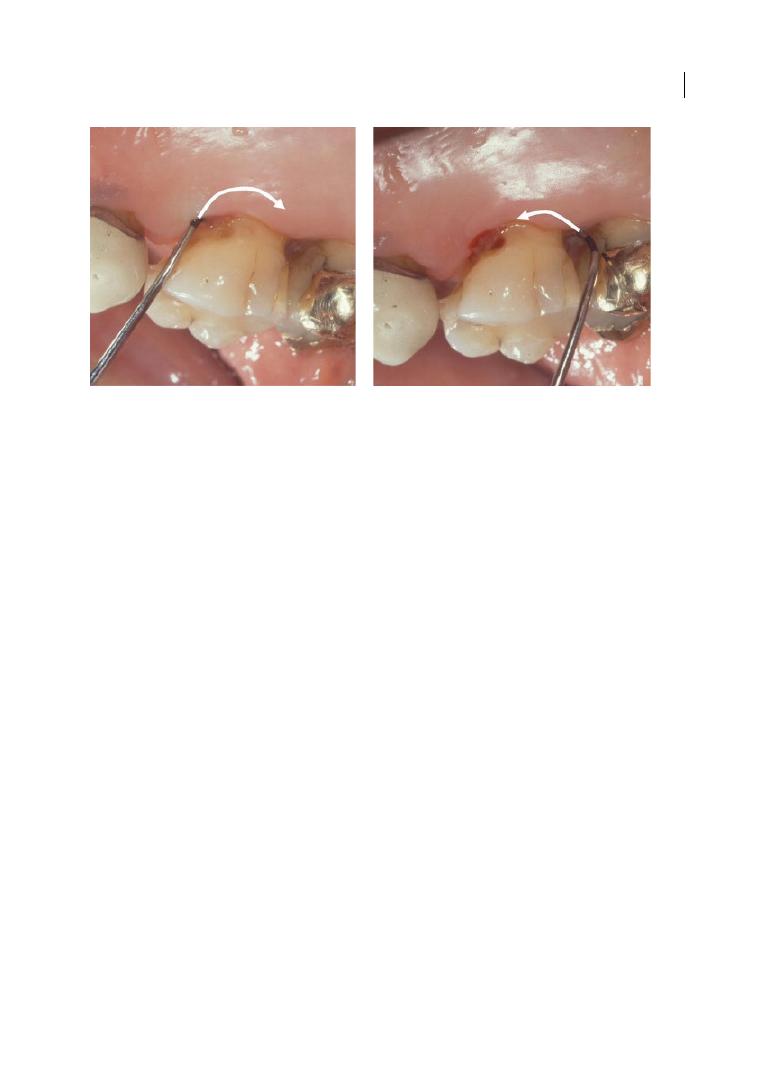

mandibular molar). Then the probe is pushed

apically, gently displacing the gingiva in

zigzag movements until the bottom of the

sulcus or pocket is reached. If the probe falls

into a pit horizontally, in most cases furca-

tion involvement has been detected.

Straight rigid periodontal probes (e.g.

PCPUNC15) are inappropriate for furcation

Table 2.1

Regularly multi‐rooted teeth with location of roots and location

of furcation entrances.

Tooth type

Location of

roots

Location of furcation

entrance

Maxillary molars

Mesio‐buccal

Disto‐buccal

Palatal

Buccal

Mesio‐palatal

Disto‐palatal

Maxillary premolars

Buccal

Palatal

Mesial

Distal

Mandibular molars

Mesial

Distal

Buccal

Lingual

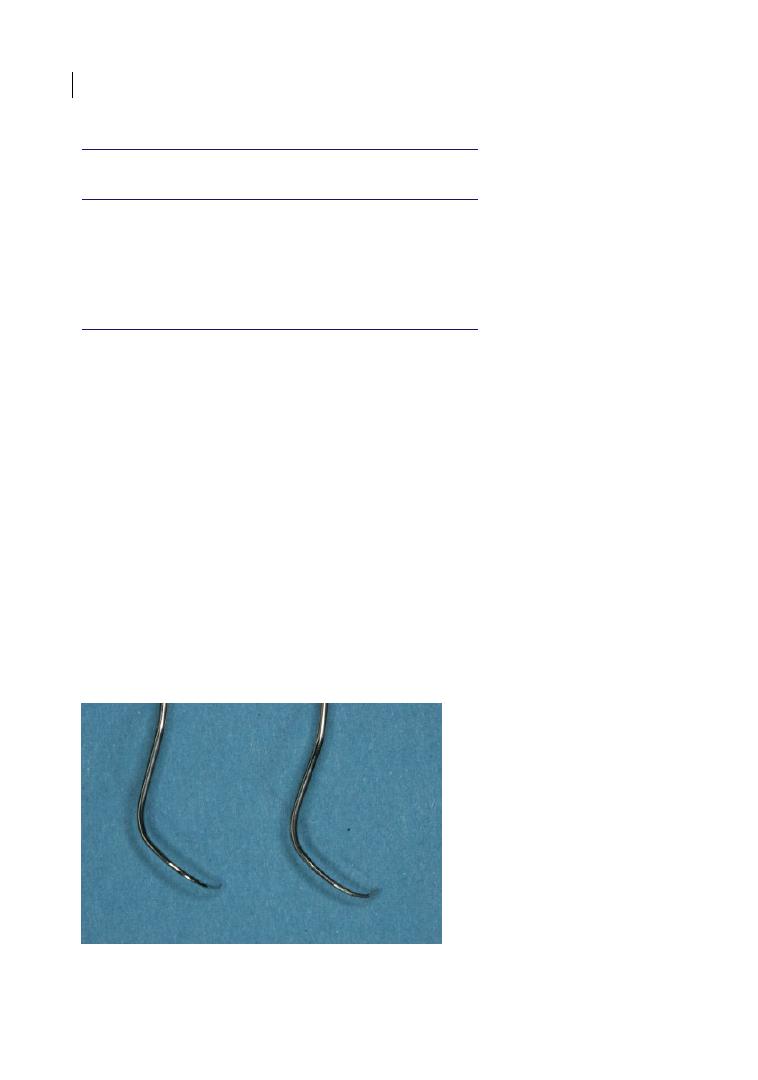

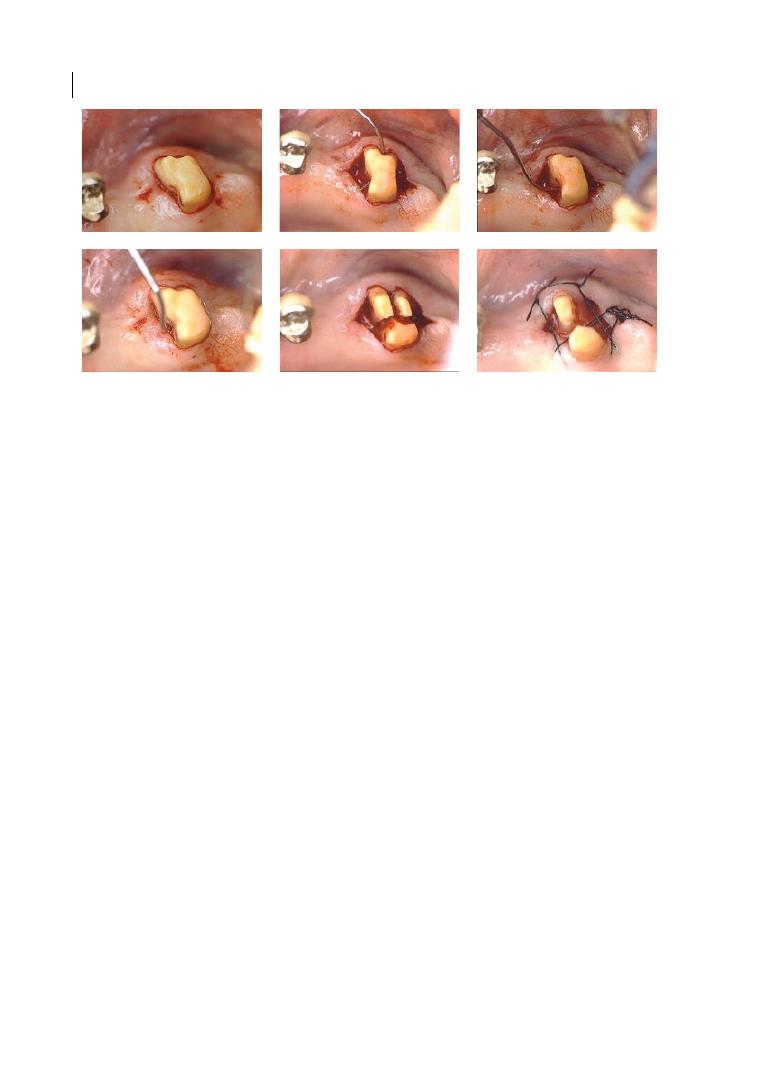

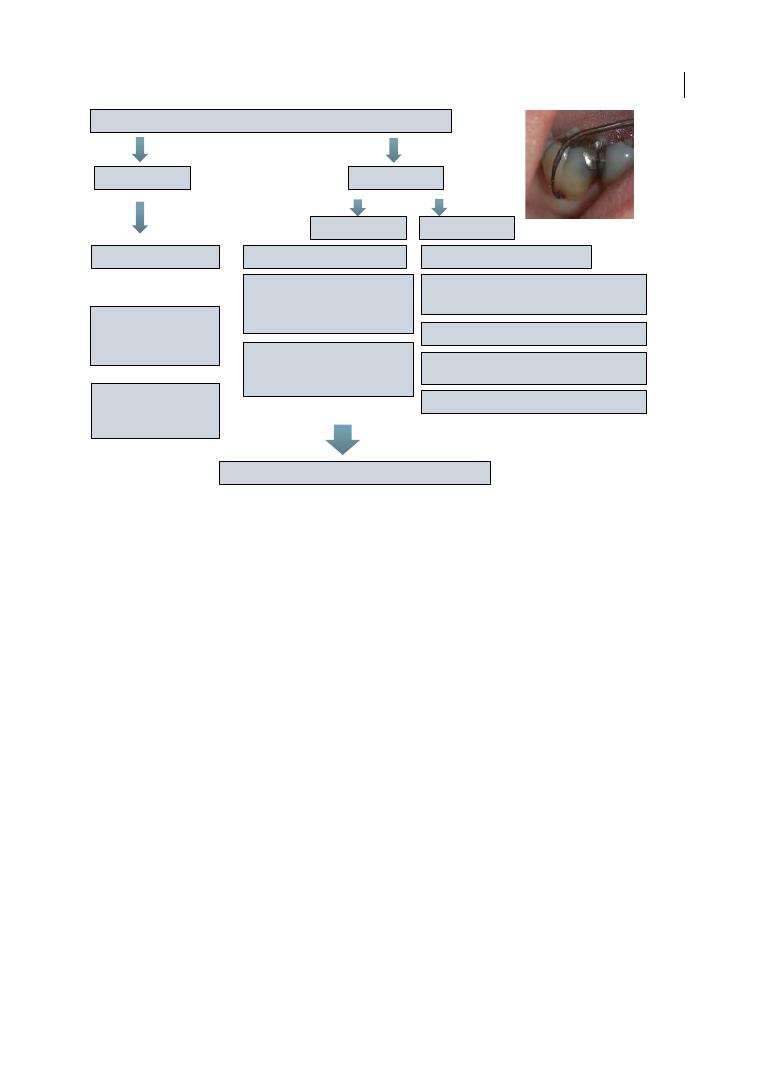

Figure 2.1

Curved furcation probes: Nabers probes (left: without markings; right: marked in 3 mm steps up to

12 mm).

Clinical and Radiographic Diagnosis and Epidemiology 17

diagnosis because they fail to follow the

curved course of most furcations. Their use

bears a high risk of underestimating the

extent of the furcation involvement (Eickholz

and Kim 1998).

2.2.1 Classification of Furcation

Involvement

Besides the simple fact of the existence of a

furcation involvement and its location, the

severity of furcation involvement is of major

significance. Severity of furcation involve-

ment is assessed by probing the respective

furcation in a horizontal direction using a

rigid curved probe (e.g. Nabers probe) and

measuring the distance from the probe tip to

a virtual tangent to the root convexities adja-

cent to the furcation (Figure 2.2). Measuring

this distance allows assessment of different

degrees of furcation involvement or the

amount of horizontal attachment loss in mil-

limetres (horizontal probing/clinical attach-

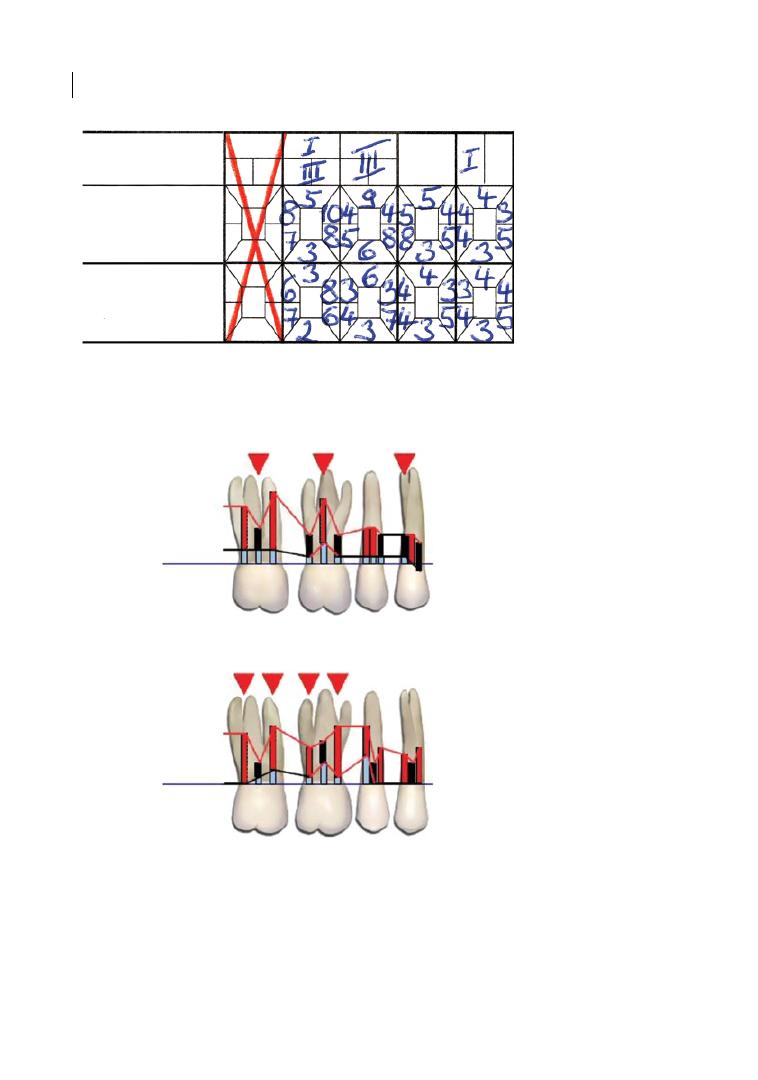

ment level: PAL‐H/CAL‐H; Figures 2.2–2.4).

Whereas assessment of the continuous vari-

able horizontal attachment loss provides

information on small changes of inter‐radicular