Gall Bladder

Assist. Prof . Dr Salah aljanaby

General surgeon and laparoscopic surgeon

Babylon medical college

Anatomy

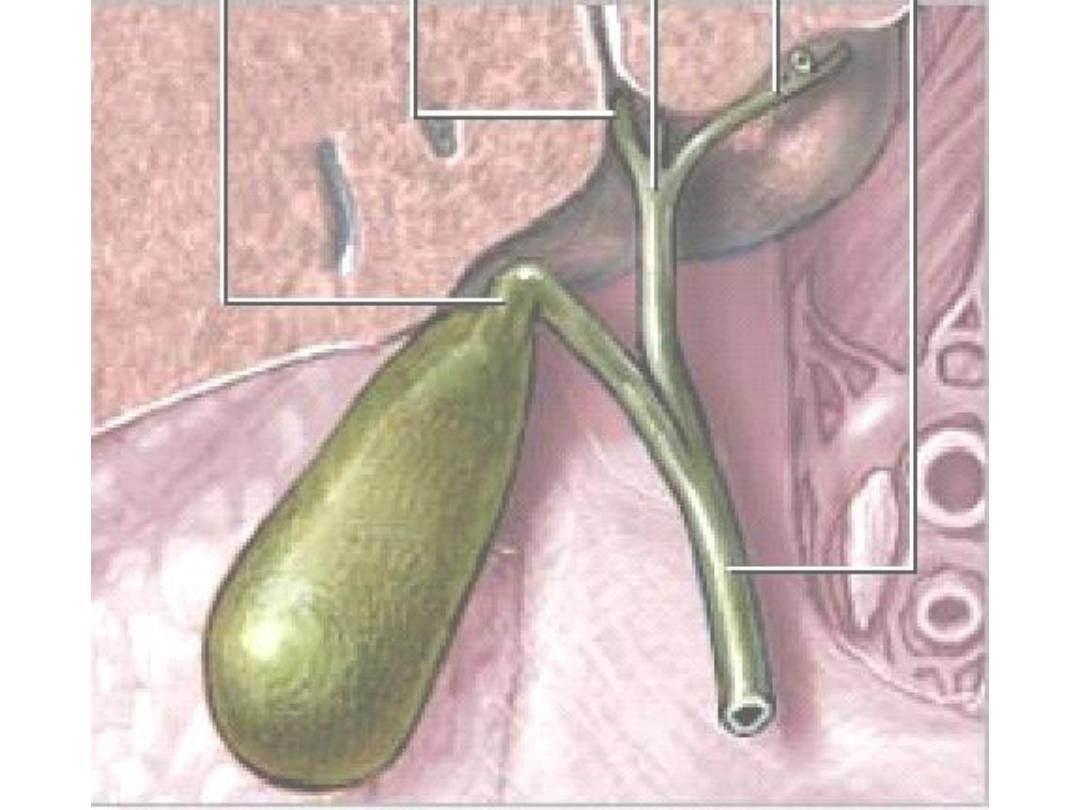

• The gallbladder (or

cholecyst, sometimes

gall bladder) is a pear-

shaped organ that

stores about 50 mL of

bile (or "gall") until the

body needs it for

digestion.

Anatomy

The gallbladder is about 7-10 cm long

in humans and appears dark green

because of its contents (bile), rather

than its tissue. It is connected to the

liver and the duodenum by the

biliary tract.

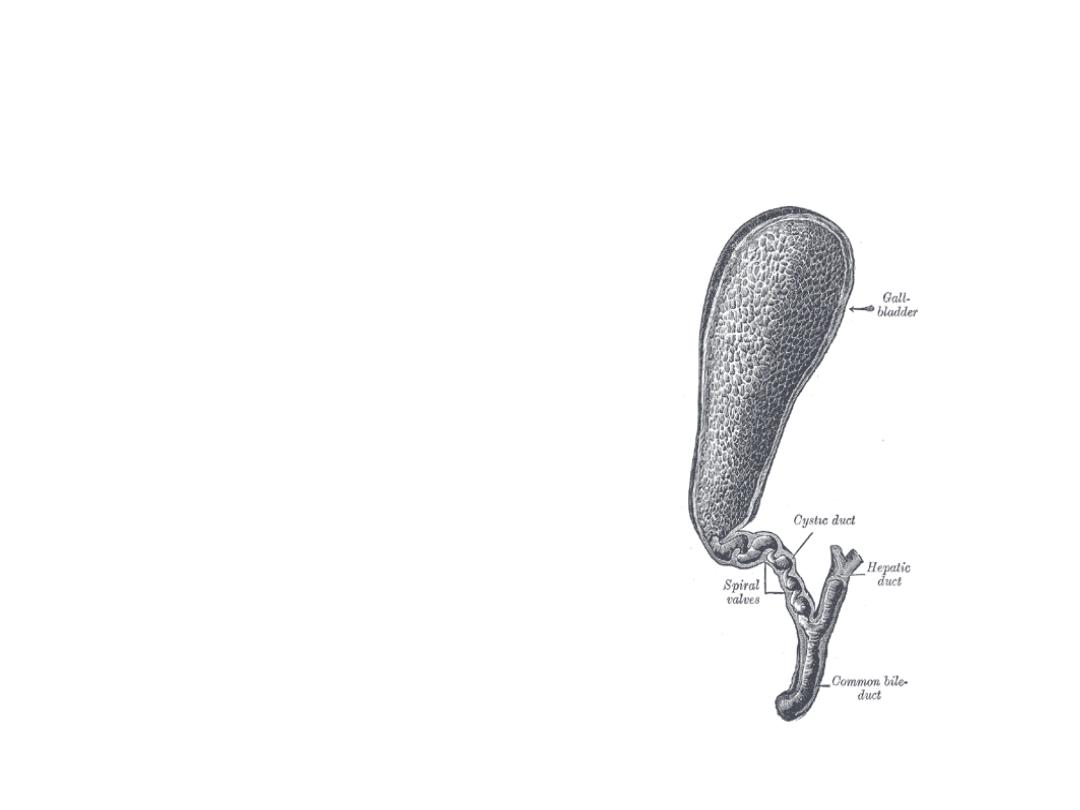

• The cystic duct leads from the

gallbladder and joins with the

common hepatic duct to form the

common bile duct.

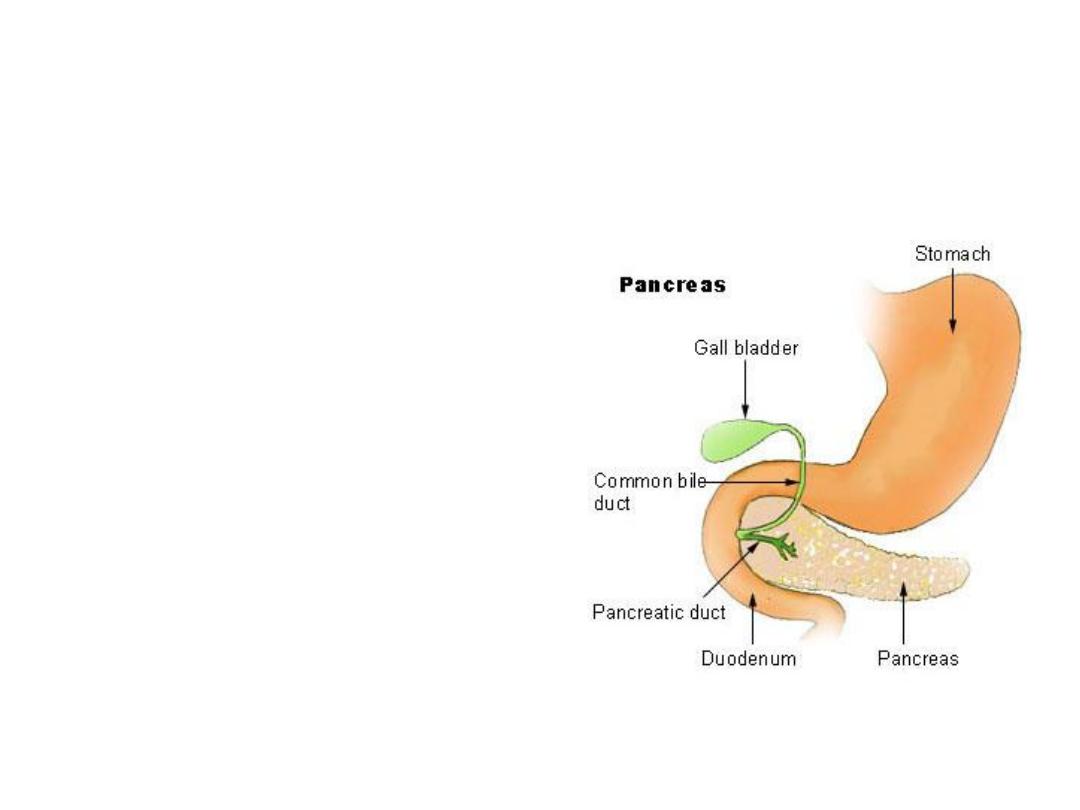

• The common bile duct then joins

with the pancreatic duct, and enters

the duodenum through the

hepatopancreatic ampulla at the

major duodenal papilla.

Anatomy

Artery

Cystic artery

Vein

Cystic vein

Nerve

Celiac ganglia, vagus

Precursor

Foregut

Histology

The layers of the gallbladder are as follows:

• The gallbladder has a simple columnar epithelial lining

characterized by recesses called Aschoff's recesses

(lacunae of Luschka) , which are pouches inside the lining.

• Under the epithelium there is a layer of connective tissue.

• Beneath the connective tissue is a wall of smooth muscle

that contracts in response to cholecystokinin, a peptide

hormone secreted by the duodenum.

• There is essentially no submucosa.

Function

• The gallbladder stores about 50 mL of bile , which is

released when food containing fat enters the digestive

tract, stimulating the secretion of cholecystokinin (CCK).

The bile, produced in the liver, emulsifies fats and

neutralizes acids in partly digested food.

• After being stored in the gallbladder, the bile becomes

more concentrated than when it left the liver, increasing

its potency and intensifying its effect on fats. Most

digestion occurs in the duodenum.

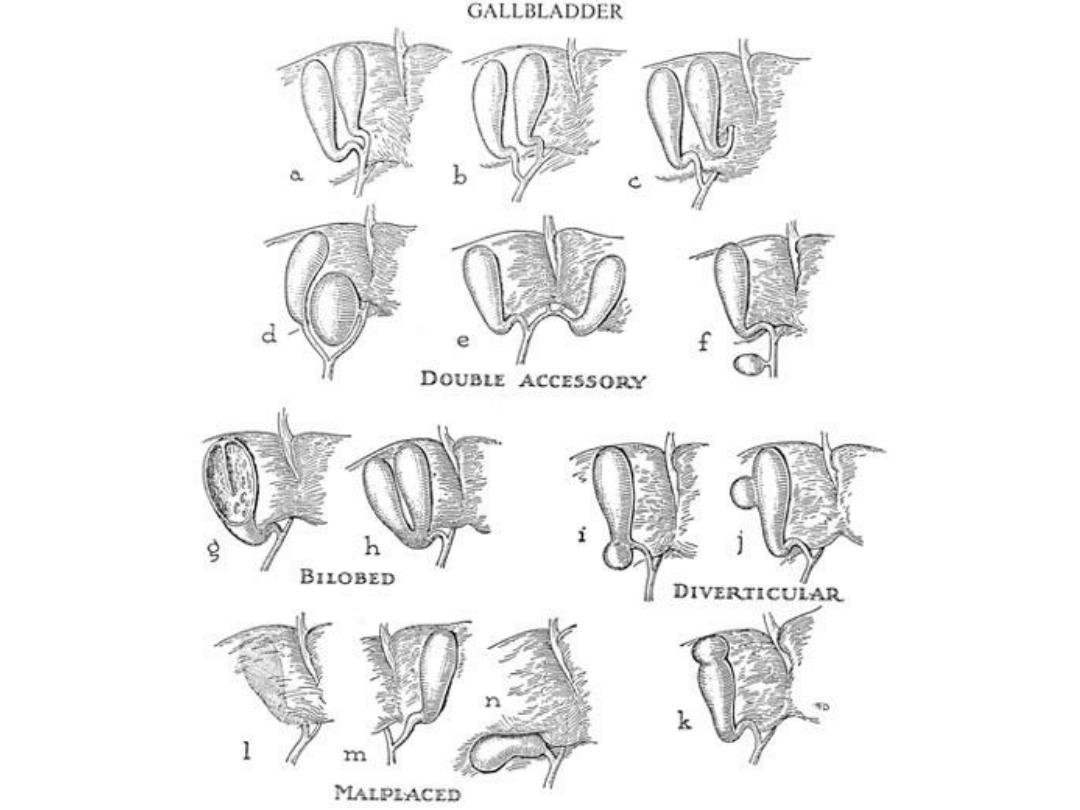

Anomalies

• The gallbladder may be absent = 0.075%

• The gallbladder and cystic duct may be absence.

• the gallbladder is irregular in form or constricted

across its middle; more rarely, it is partially

divided in a longitudinal direction.

• two distinct gallbladders, each having a cystic duct

that joined the hepatic duct. (0.026%), The cystic

duct may itself be doubled

• The gallbladder has been found on the left side (to

the left of the ligamentum teres) in subjects in

whom there was no general tranposition of the

thoracic and abdominal viscera.

• The gallbladder may be intrahepatic or

beneath the left lobe. Ectopic sites include

retrohepatic positions, or in the anterior

abdominal wall or falciform ligament, they

may be suprahepatic or transversely

position, floating, or retroperitoneal. They

may be in the midline anterior epigastric

above the left lobe or suprahepatic above

the right hepatic lobe.

Choledochal cyst

• Choledochal cysts are congenital anomalies of the

bile ducts. They consist of cystic dilatations of the

extrahepatic biliary tree, intrahepatic biliary

radicles, or both.

• Douglas is credited with the first clinical report in a

17-year-old girl who presented with intermittent

abdominal pain, jaundice, fever, and a palpable

abdominal mass.

• Pathophysiology: The pathogenesis of choledochal

cysts is most likely multifactorial.

– A congenital etiology,

– A congenital predisposition to acquiring the disease

under the right conditions.

• The vast majority of patients with

choledochal cysts have an anomalous

junction of the common bile duct with the

pancreatic duct (anomalous pancreatobiliary

junction [APBJ]). An APBJ is characterized

when the pancreatic duct enters the common

bile duct 1 cm or more proximal to where the

common bile duct reaches the ampulla of

Vater.

• APBJs in more than 90% of patients with

choledochal cysts.

• The APBJ allows pancreatic secretions and

enzymes to reflux into the common bile duct.

In the relatively alkaline conditions found in

the common bile duct, pancreatic pro-

enzymes can become activated. This results

in inflammation and weakening of the bile

duct wall. Severe damage may result in

complete denuding of the common bile duct

mucosa.

• From a congenital standpoint, defects in

epithelialization and recanalization of the

developing bile ducts during organogenesis

and congenital weakness of the duct wall

have also been implicated. The result is

formation of a choledochal cyst.

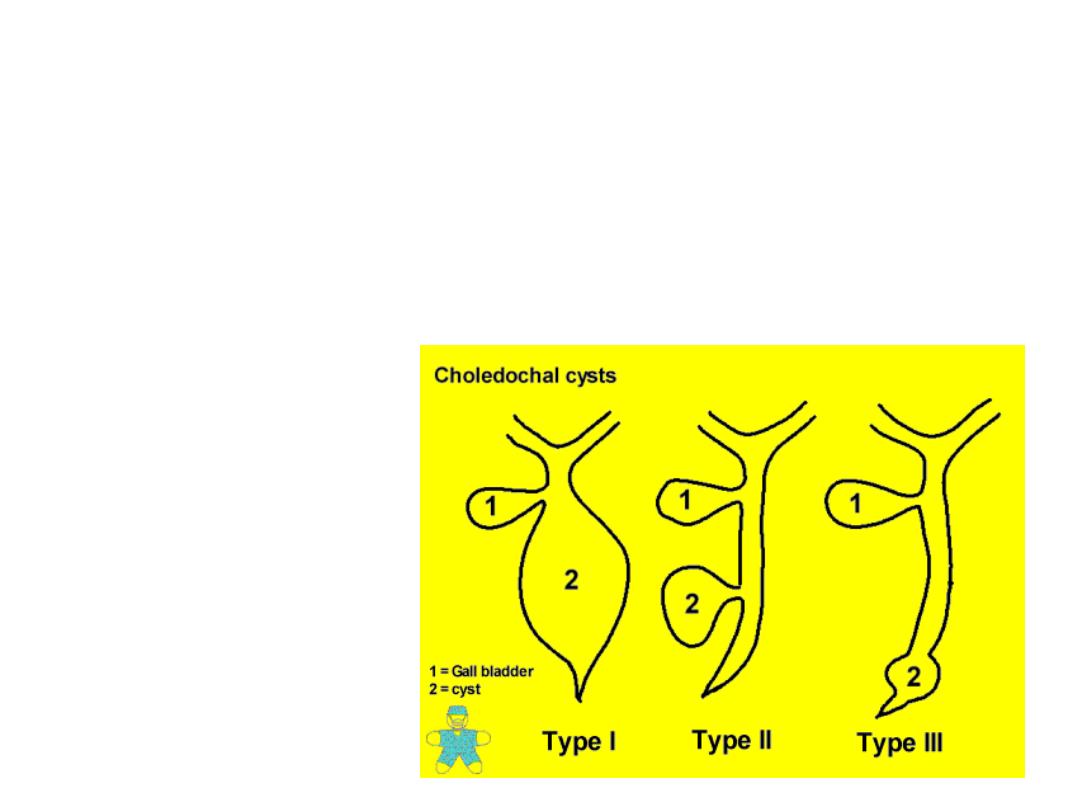

Anatomy of Choledochal cyst

based on the Todani classification published

in 1977.

• Type I choledochal cysts

– most common ; 80-90% of the lesions.

– Type I cysts are dilatations of the entire common

hepatic and common bile ducts or segments of each.

– They can be saccular or fusiform in configuration.

• Type II choledochal cysts

– isolated protrusions or diverticula that project from the

common bile duct wall. They may be sessile or may be

connected to the common bile duct by a narrow stalk.

• Type III choledochal cysts are found in the

intraduodenal portion of the common bile duct.

Another term used for these cysts is

choledochocele.

• Type IVA cysts are characterized by multiple

dilatations of the intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary

tree. Most frequently, a large solitary cyst of the

extrahepatic duct is accompanied by multiple cysts of

the intrahepatic ducts. Type IVB choledochal cysts

consist of multiple dilatations that involve only the

extrahepatic bile duct.

• Type V choledochal cysts are defined by dilatation of

the intrahepatic biliary radicles. Often, numerous

cysts are present with interposed strictures that

predispose the patient to intrahepatic stone

formation, obstruction, and cholangitis. The cysts are

typically found in both hepatic lobes. Occasionally,

unilobar disease is found and most frequently

involves the left lobe.

• The patient may present at any age with

1. Obstructive jaundice

2. Cholangitis and

3. Abd signs, with RUQ swelling in some cases

• It is a premalignant condition

• Diagnosis by US and MRI

• Radical excision of the cyst is the treatment

of choice with Roux – en –Y reconstruction

Gall stones

• Gall stones are the most common abdominal reason for

admission to hospital in developed countries and account

for an important part of healthcare expenditure. Around

5.5 million people have gall stones in the United Kingdom,

and over 50 000 cholecystectomies are performed each

year.

• Normal bile consists of 70% bile salts (mainly cholic and

chenodeoxycholic acids), 22% phospholipids (lecithin), 4%

cholesterol, 3% proteins, and 0.3% bilirubin.

• There are two major types of gallstones, which seem to

form due to distinctly different pathogenetic mechanisms.

Cholesterol Stones

• About 90% of gallstones are of this type.

These stones can be either;

– almost pure cholesterol {Cholesterol stones}

– or mixtures of cholesterol and other

substances{ cholesterol predominant (mixed)

stones}.

• The key event leading to formation and

progression of cholesterol stones is

precipitation of cholesterol in bile.

• Unesterified cholesterol is virtually

insoluble in aqueous solutions and is kept

in solution in bile largely by virtue of the

detergent-like effect of bile salts.

Imbalance lead to stone formation

• Hyper-secretion of cholesterol into bile due

to

– obesity,

– acute high calorie intake,

– chronic polyunsaturated fat diet, contraceptive

steroids or pregnancy,

– diabetes mellitus and

– certain forms of familial hypercholesterolemia.

• Hypo-secretion of bile salts due to

– impaired bile salt synthesis and

– abnormal intestinal loss of bile salts (e.g. recirculation

failure due to ileal disease).

• Impaired gallbladder function with incomplete

emptying or stasis.

– seen in late pregnancy

– with oral contraceptive use,

– in patients on total parenteral nutrition and

– due to unknown causes, perhaps associated with

neuro-endocrine dysfunction.

• There are clearly important genetic

determinants for cholesterol stone

formation. For example, the prevelance of

the disease in descendents of Chilean,

Indians and in American Indians is

extraordinarily high and not accounted for by

environment.

• There is also an important sex bias in

development of stones - the prevelance in

adult females is two to three times that seen

in males

Age >40 years

Bile salt loss (ileal

disease or resection)

Female sex (twice risk in men)

Diabetes mellitus

Genetic or ethnic variation

Cystic fibrosis

High fat, low fibre diet

Antihyperlipidaemic

drugs(clofibrate)

Obesity

Gallbladder dysmotility

Pregnancy (risk increases with

number of pregnancies)

Prolonged fasting

Hyperlipidaemia

Total parenteral

nutrition

•

Pigment Stones

• Roughly 10% of gallstones are pigment

stones

composed of large quantities of bile pigments,

along with lesser amounts of cholesterol and

calcium salts.

• Black pigment stones

– consist of 70% calcium bilirubinate and are

more common in patients with haemolytic

diseases (sickle cell anaemia, hereditary

spherocytosis, thalassaemia) and cirrhosis.

• Brown pigment stones (accounting for <5%

of stones)

– They form as a result of stasis and infection

within the biliary system, usually in the

presence of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp,

which produce β glucuronidase that converts

soluble conjugated bilirubin back to the

insoluble unconjugated state leading to the

formation of soft, earthy, brown stones.

– Ascaris lumbricoides and Opisthorchis senensis

have both been implicated in the formation of

these stones, which are common in South East

Asia.

Effects and complications of Gall Stones

In the GB:

• Silent stones

• Chronic cholecystitis

• Acute cholecystitis

• Gangrene

• Perforation

• Empeyma

• Mucocele

• carcinoma

In the bile ducts:

• Obstructive jaundice

• Cholangitis

• Acute pancreatitis

In the intestine:

• Acute intestinal

obstruction (Gall

stone ileus)

Cholecystitis

Definition

• Cholecystitis refers to a painful inflammation of the

gallbladder's wall. The disorder can occur a single

time (acute), or can recur multiple times (chronic).

• Cholecystitis is defined as inflammation of the

gallbladder that occurs most commonly because of an

obstruction of the cystic duct from cholelithiasis.

Ninety percent of cases involve stones in the cystic

duct (ie, calculous cholecystitis), with the other 10%

representing acalculous cholecystitis. Although bile

cultures are positive for bacteria in 50-75% of cases,

bacterial proliferation may be a result of cholecystitis

and not the precipitating factor.

Causes

• Risk factors for calculous cholecystitis mirror

those for cholelithiasis and include the

following:

– Female sex

– Certain ethnic groups (Race)

– Obesity or rapid weight loss

– Drugs (especially hormonal therapy in women)

– Pregnancy

– Increasing age

• Acalculous cholecystitis is related to

conditions associated with biliary stasis,

to include the following:

–Critical illness

–Major surgery or severe trauma/burns

–Sepsis

–Long-term TPN

–Prolonged fasting

• Other causes of acalculous cholecystitis

include the following:

– Cardiac events, including myocardial infarction

– Sickle cell disease

– Salmonella infections

– Diabetes mellitus

– Patients with AIDS with cytomegalovirus,

cryptosporidiosis, or microsporidiosis

• Idiopathic cases exist.

History

• Typical gallbladder colic is 1-5 hours of constant

pain, most commonly in the epigastrium or right

upper quadrant. Pain may radiate to the right

scapular region or back. Peritoneal irritation by

direct contact with the gallbladder localizes the

pain to the right upper quadrant. Pain is severe,

dull or boring, and constant (not colicky). Patients

tend to move around to seek relief from the pain.

Onset of pain develops hours after a meal, occurs

frequently at night, and awakens the patient from

sleep.

• Associated symptoms include nausea, vomiting,

pleuritic pain, and fever.

• Indigestion, belching, bloating, and fatty food

intolerance are thought to be typical

symptoms of gallstones; however, these

symptoms are just as common in people

without gallstones and frequently are not

cured by cholecystectomy.

• Most gallstones (60-80%) are asymptomatic

at a given time. Smaller stones are more

likely to be symptomatic than larger ones.

Almost all patients develop symptoms prior

to complications.

• Symptoms of cholecystitis are steady pain in

the right hypochondrium or epigastrium,

nausea, vomiting, and fever. Acute attack

often is precipitated by a large or fatty meal.

Physical

• Vital signs parallel the degree of illness. Patients

with cholangitis are more likely to have fever,

tachycardia, and/or hypotension. Patients with

gallbladder colic have relatively normal vital signs.

• Patients with cholecystitis are usually more ill

appearing than simple biliary colic patients, and

they usually lie still on the examination table since

any movement may aggravate any peritoneal

signs.

• Abdominal examination;

– Epigastric or RUQ tenderness and abdominal

guarding.

– The Murphy sign (an inspiratory pause on

palpation of the right upper quadrant) can be

found on abdominal examination.

– Positive Murphy sign was extremely sensitive

(97%) and predictive (PPV, 93%) for

cholecystitis. However, in elderly patients, this

sensitivity may be decreased.

• peritoneal signs should be taken seriously. Most

uncomplicated cholecystitis does not have

peritoneal signs; thus, search for complications

(eg, perforation, gangrene) or other sources of

pain.

• Gallbladder gangrene can be a complication in up

to 20% of cases of cholecystitis and is usually in

diabetics, elderly, or immunocompromised

persons.

• A palpable fullness in the RUQ may be

appreciated in 20% of cases.

• As in all patients with abdominal pain, perform a

complete physical examination, including rectal

and pelvic examinations in women.

• In elderly patients and those with diabetes, occult

cholecystitis or cholangitis may be the source of

fever, sepsis, or mental status changes.

• Jaundice is unusual in the early stages of acute

cholecystitis and may be found in fewer than 20%

of patients.

• A very high bilirubin =think for common bile duct

and pancreatic region disease.

DD

Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm

Acute Mesenteric Ischemia

Amebic Hepatic Abscesses

Appendicitis

Biliary Colic

Biliary Disease

Cholangiocarcinoma

Cholangitis

Choledocholithiasis

Cholelithiasis

Gallbladder Cancer

Gallbladder Mucocele

Gallbladder Tumors

Gastric Ulcers

Gastritis, Acute

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

Hepatitis, Viral

Myocardial Infarction

Nephrolithiasis

Pancreatitis, Acute

Peptic Ulcer Disease

Pneumonia, Bacterial

Pregnancy and Urolithiasis

Pyelonephritis, Acute

Renal Disease and Pregnancy

Renal Vein Thrombosis

Lab Studies

• Labs with cholelithiasis and gallbladder colic

should be completely normal.

• Because biliary obstruction is limited to the

gallbladder in uncomplicated cholecystitis,

elevation in the serum total bilirubin and alkaline

phosphatase concentrations may not be present.

• An elevated WBC is expected but not reliable. Only

61% of patients with cholecystitis had a WBC

greater than 11,000. A WBC greater than 15,000

may indicate perforation or gangrene.

• Mild elevation of amylase up to 3 times normal

may be found in cholecystitis, especially when

gangrene is present.

• Prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial

thromboplastin time (aPTT) are not expected to be

elevated unless sepsis or underlying cirrhosis is

present. Coagulation profiles are helpful if the

patient needs operative intervention.

• For febrile patients, send 2 sets of blood cultures

to attempt to isolate the organism.

• Although expected to be normal, urinalysis is

essential in the workup of patients with abdominal

pain to exclude pyelonephritis and renal calculi.

• Conduct a pregnancy test for women of

childbearing age.

Imaging Studies

• Ultrasound and nuclear medicine studies

are the best imaging studies for the

diagnosis of both cholecystitis and

cholelithiasis. Plain radiography, CT scans,

and endoscopic retrograde

cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) are

diagnostic adjuncts.

Abd. radiographs (Plain X-Ray)

• Adominal radiographs have low

sensitivity and specificity in

evaluating biliary system pathology,

but

• They can be helpful in excluding

other abdominal pathology such as

renal colic, bowel obstruction,

perforation. Between 10 and 30% of

stones have a ring of calcium and,

therefore, are radiopaque. A

porcelain gallbladder also may be

observed on plain films.

• Emphysematous cholecystitis, cholangitis,

cholecystic-enteric fistula, or postendoscopic

manipulation may show air in the biliary

tree. Air in the gallbladder wall indicates

emphysematous cholecystitis due to gas-

forming organisms such as clostridial species

and Escherichia coli.

Computed tomography scan

• CT scan is recommended only for the evaluation of

abdominal pain if the diagnosis is uncertain. CT scan can

demonstrate gallbladder wall edema, pericholecystic

stranding and fluid, and high-attenuation bile.

• Advantages: For complications of cholecystitis and

cholangitis, gallbladder perforation, pericholecystic fluid,

and intrahepatic ductal dilation, CT scan may be

adequate. CT scan provides better information of the

surrounding structures than sonogram and HIDA. CT scan

is also noninvasive.

• Disadvantages: CT scan misses 20% of gallstones because

the stones may be of the same radiographic density as

bile. CT scan is also more expensive and takes longer since

the patient usually has to drink oral contrast. Also, given

the radiation dose, it may not be ideal in the pregnant

patient.

Ultrasound

• An ultrasound is the most common test used

for the diagnosis of biliary colic and acute

cholecystitis. It is 90-95% sensitive for

cholecystitis and 78-80% specific. For simple

cholelithiasis, it is 98% sensitive and specific.

Findings include gallstones or sludge and

one or more of the following conditions

• Gallbladder wall thickening (>2-4 mm) - False-

positive wall thickening found in

hypoalbuminemia, ascites, congestive heart

failure, and carcinoma

• Gallbladder distention (diameter >4 cm, length

>10 cm)

• Pericholecystic fluid from perforation or exudate

• Air in the gallbladder wall (indicating gangrenous

cholecystitis)

• Sonographic Murphy sign (86-92% sensitive, 35%

specific), pain when the probe is pushed directly

on the gallbladder (not related to breathing)

• Some sonographers recommend the diagnosis of

cholecystitis if both a sonographic Murphy sign

and gallstones (without evidence of other

pathology) are present.

• Additional findings in the presence or absence of

gallstones: Dilated common bile duct or dilated

intrahepatic ducts of the biliary tree indicate

common bile duct stones. In the absence of

stones, a solitary stone may be lodged in the

common bile duct, a location difficult to visualize

sonographically.

• Advantages of sonography include the following:

– Images other structures (eg, aorta, pancreas, liver)

– Identifies complications (eg, perforation,

empyema, abscess)

– Rapidly performed at the bedside

– No radiation (important in pregnancy)

• Disadvantages of sonography include the following:

– Operator dependent and patient dependent

– Inability to image the cystic duct

– Decreased sensitivity for common bile duct stones

• Biliary scintigraphy (HIDA, diisopropyl

iminodiacetic acid [DISIDA]), nuclear

medicine studies

– Sonography or nuclear medicine testing is the

test of choice for cholecystitis. HIDA scans have

sensitivity (94%) and specificity (65-85%) for

acute cholecystitis. They are sensitive (65%) and

specific (6%) for chronic cholecystitis. Oral

cholecystography is not practical for the ED.

– HIDA and DISIDA scans are functional studies of

the gallbladder. Technetium-labeled analogues

of iminodiacetic acid (IDA) or diisopropyl IDA-

DISIDA are administered intravenously (IV) and

secreted by hepatocytes into bile, enabling

visualization of the liver and biliary tree.

– Normal scans are characterized by normal

visualization of gallbladder in 30 minutes.

– With cystic duct obstruction (cholecystitis), the

HIDA scan shows nonvisualization (ie,

considered positive) of the gallbladder at 60

minutes and uptake in the intestine as the bile is

excreted directly into the duodenum.

– Obstruction of the common bile duct causes

nonvisualization of the small intestine.

– The rim sign is increased tracer adjacent to the

gallbladder at 60 minutes and suggests

gangrenous cholecystitis.

• Advantages of HIDA/DISIDA scans include the

following:

– Assessment of function

– Normal-appearing gallbladder (by ultrasound);

obstructed cystic duct abnormal on DISIDA scan but

not ultrasound.

– Simultaneous assessment of bile ducts

• Disadvantages of HIDA/DISIDA scans include the

following:

– High bilirubin (>4.4 mg/dL) possibly decreases

sensitivity

– Recent eating or fasting for 24 hours also possibly

affects study

– No imaging of other structures in the area

• Other Tests:

– Endoscopic retrograde

cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)

• ERCP provides both endoscopic and radiographic

visualization of the biliary tract. It can be diagnostic

and therapeutic by direct removal of common bile

duct stones.

– Magnetic Resonance cholangiopancreatography

(MRCP)

TREATMENT; Conservative treatment

followed by cholecystectomy

Symptoms of acute cholecystitis subside with

conservative treatment in 90 % of cases

– Four principles

1. Naso-gastric suction & IV fluid

2. analgesics

3. Antibiotics (broad spectrum effective against Gm –

ve aerobes)

4. Subsequent management ( if inflame. Subside→

oral fluids → fat free diet)

Cholecystectomy on the next available list or after 4-

6 wks

• Conservative treatment is not advised if there is:

1. Uncertain diagnosis

2. The possibility of high retrocecal appendix or

3. Perforated DU cannot be excluded

• Conservative treatment must be abandoned if

pain and tenderness increased →percutaneous

cholecystostomy → subsequent cholecystectomy

TREATMENT; Routine early operations

Indications:

1. Within 24 hrs of the onset of the attack

2. Experienced surgeons

3. Excellent operating facilities

• cholecystectomy can be done either by

open or laparoscopic approaches

Acalcuolous cholecystitis

• Some patients have non-specific inflammation of

the GB , wherease other have one of the

Cholecystoses

• Diagnosis either by oral cholecystography (

chronic cases) or by isotopic scanning (acute

cases)

• Cholesterol crystal in the duod. aspirate may help

diagnosis

Acute acalcuolous cholecystitis is seen more

frequently in:

• Critical illness

• Major surgery or severe trauma/burns

• Sepsis

• Long-term TPN

• Prolonged fasting

The Cholecystoses

• Not uncommon conditions affecting

the GB where there is chronin

inflamm. Changes with hyperplasia

of of all tissue elemnts

Cholesterosis (Strawberry GB)

• Submucous aggregations of

cholesterol crystals and cholesterol

esters (yellow seeds) in the red

mucosa

Cholesterol polyposis of the GB

• These are either cholesterol polyposis or

adenomatous changes

Cholecystitis glandularis proliferans (polyp,

adenomyomatosis and intramural diverticuolosis)

• MM polyps- fleshy and granuolomatous

• All layer of GB may be thickened

• Sometimes incomplete septums forms

• Intraparietal mixed calculi may be present

Diverticuolosis of the GB

• Usually manifest as black pigment stones

impacted in the out-pouchings of the lacunae of

Luschka

Typhoid GB

• S. Typhi or occasionally S Typhimurium can infect

the GB leading to acute cholecystitis and more

commonly chronic cholecystitis

• The patient being typhoid carrier excreting the

bacteria in the bils

• Gall stones may be present

GB cancer

• Rare ( common in certain area as India where it reaches 9% of

biliary tract disease

• Found in less than 1% of GB operations

• In over 90 % of cases gall stones are present

Presentations

• Age= 70s

• Sex= female (F-M= 5-1)

Pathology

• Scirrhous, but may be squamous cell & mixed squamous

adenocarcinoma

• Spread= direct, lymphatics and veins

Clinical P

• Either extensive mass in the liver during

investigations for jaundice or

• At cholecystectomy at the time the histology is

received

Treatment

• Those diagnosed at cholecystectomy and

confined to the mucosa have a good prognosis

(add wide excision & LN clearance or not ??)

• Large T reaching serosa= chemoradiotherapy

• Median survival 1 year