The Acute Abdomen

:

"An acute abdomen" is any sudden, spontaneous, nontraumatic

disorder whose chief manifestation is in the abdominal area and

for which urgent operation may be necessary. Because there is

frequently a progressive underlying intra-abdominal disorder,

undue delay in diagnosis and treatment adversely affects outcome.

The approach to a patient with an acute abdomen must be orderly

and thorough. An acute abdomen must be suspected even if the

patient has only mild or atypical complaints. The history and

physical examination should suggest the probable causes and

guide the choice of initial diagnostic studies..

History Abdominal Pain

History taking by an experienced physician is an active process

whereby a cluster of diagnostic possibilities is considered in order

to systematically eliminate less likely conditions. Pain is the most

common and predominant presenting feature of an acute abdomen.

Careful consideration of the location, the mode of onset and

progression, and the character of the pain will suggest a

preliminary list of differential diagnoses.

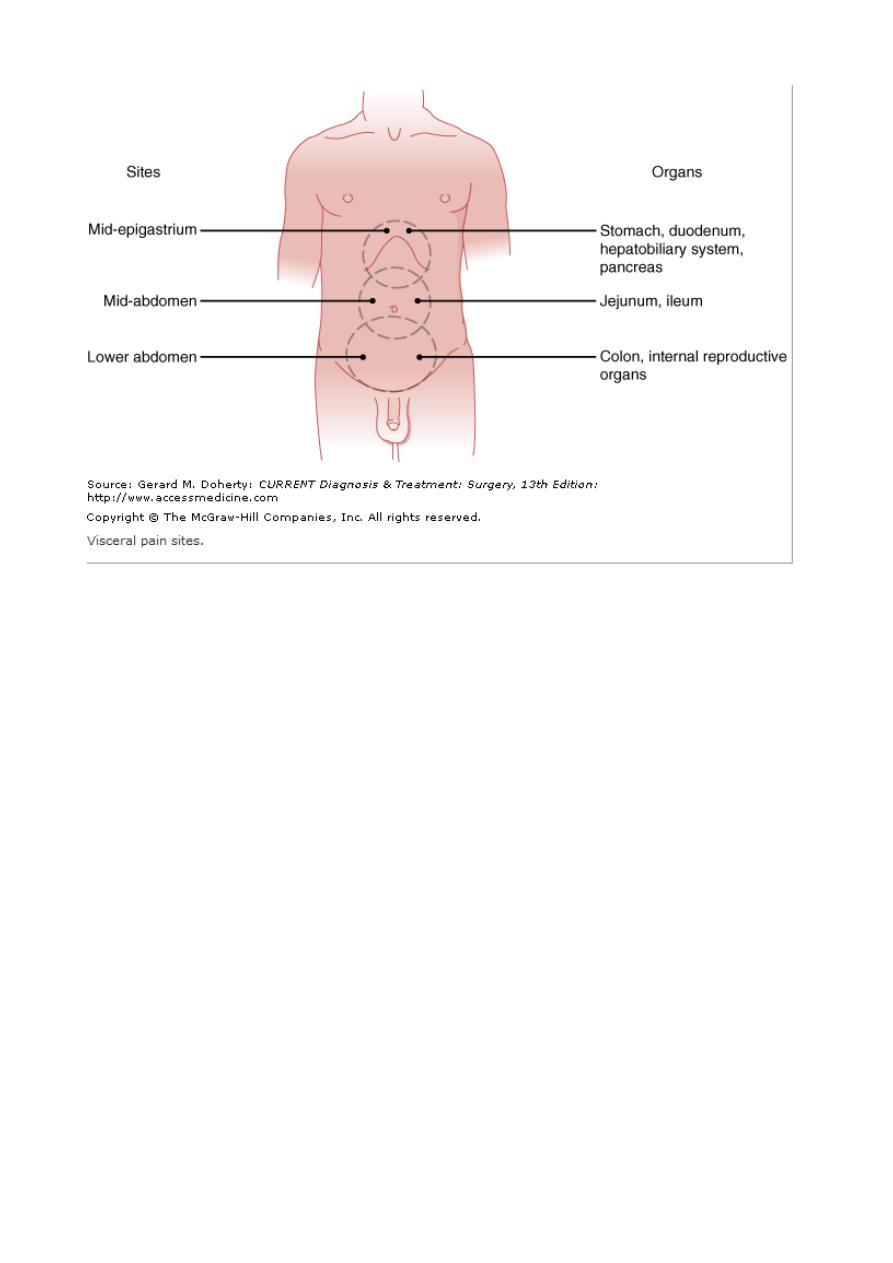

Location

of Pain

Because of the complex dual visceral and parietal sensory network

innervating the abdominal area, pain is not as precisely localized

as in the extremities.. Visceral sensation is mediated primarily by

afferent C fibers located in the walls of hollow viscera and in the

capsules of solid organs. Unlike cutaneous pain, visceral pain is

elicited by distention, by inflammation or ischemia stimulating the

receptor neurons, or by direct involvement (eg, malignant

infiltration) of sensory nerves. The centrally perceived sensation is

generally slow in onset, dull, poorly localized, and protracted.

Because of this, increased wall tension due to luminal distention

or forceful smooth muscle contraction (colic) produces diffuse,

deep-seated pain felt in the midepigastrium, periumbilical area,

lower abdomen, or flank areas .. Visceral pain is most often felt in

the midline because of the bilateral sensory supply to the spinal

cord

By contrast, parietal pain is mediated by both C and A delta

nerve fibers, the latter being responsible for the transmission of

more acute, sharper, better-localized pain sensation. Direct

irritation of the somatically innervated parietal peritoneum

(especially the anterior and upper parts) by pus, bile, urine, or

gastrointestinal secretions leads to more precisely localized pain.

The cutaneous distribution of parietal pain corresponds to the T6–

L1 areas. Parietal pain is more easily localized than visceral pain

because the somatic afferent fibers are directed to only one side of

the nervous system.

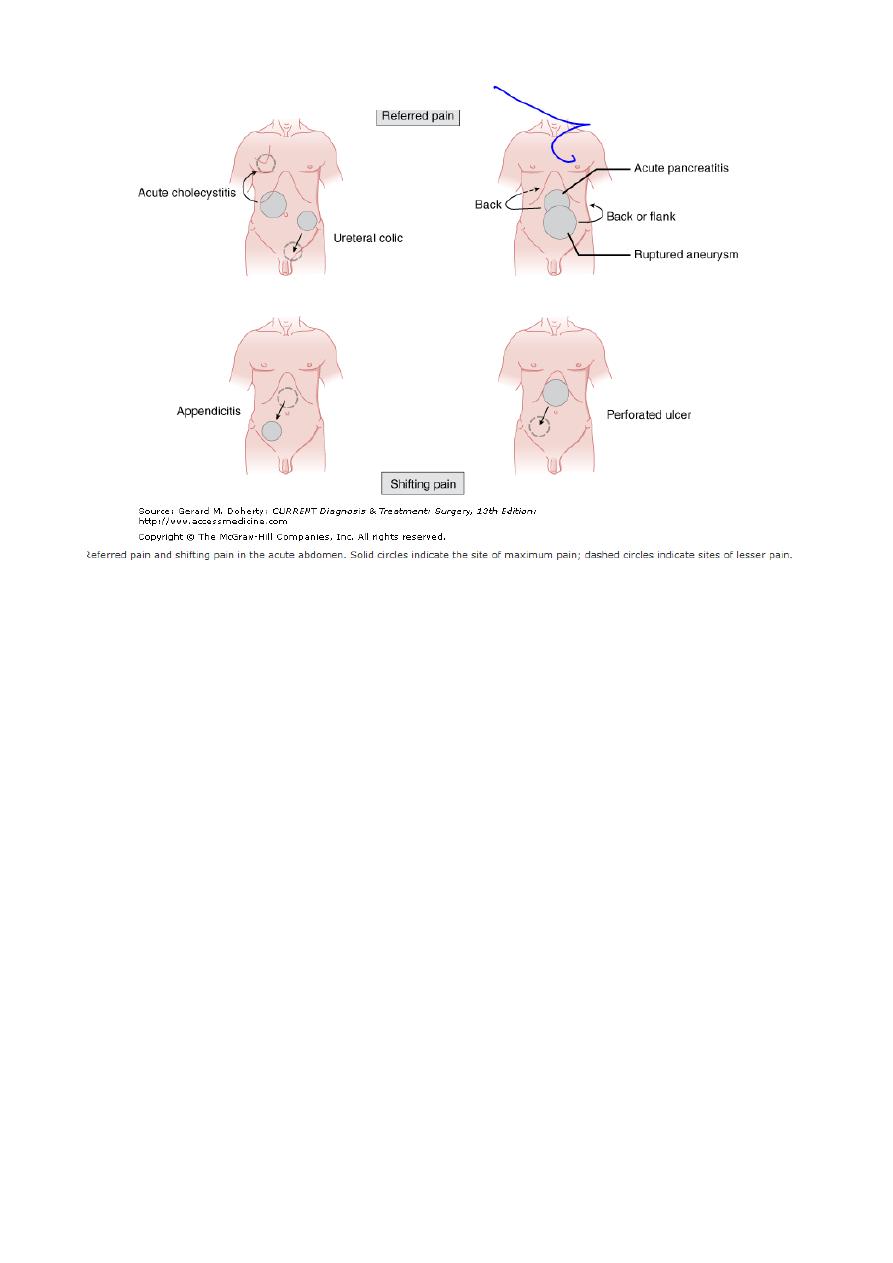

Abdominal pain may be referred or may shift to sites far removed

from the primarily affected organs .Referred pain denotes

noxious (usually cutaneous) sensations perceived at a site distant

from that of a strong primary stimulus. Distorted central

perception of the site of pain is due to the confluence of afferent

nerve fibers from widely disparate areas within the posterior horn

of the spinal cord. For example, pain due to subdiaphragmatic

irritation by air, peritoneal fluid, blood, or a mass lesion is referred

to the shoulder via the C4-mediated (phrenic) nerve. Pain may

also be referred to the shoulder from supradiaphragmatic lesions

such as pleurisy or lower lobe pneumonia, especially in young

patients. Although more often perceived in the right scapular

region, referred biliary pain may mimic angina pectoris if it is

perceived in the anterior chest or left shoulder areas. Posterolateral

right flank pain may be seen in retrocecal appendicitis.

Spreading or shifting pain. Beginning classically in the

epigastric or periumbilical region, the incipient visceral pain of

acute appendicitis (due to distention of the appendix) later shifts to

become sharper parietal pain localized in the right lower quadrant

when the overlying peritoneum becomes directly inflamed . In

perforated peptic ulcer, pain almost always begins in the

epigastrium, but as the leaked gastric contents track down the right

paracolic gutter, pain may descend to the right lower quadrant

with even diminution of the epigastric pain.

The location of pain serves only as a rough guide to the

diagnosis—"typical" descriptions are reported in only two thirds

of cases. This great variability is due to atypical pain patterns, a

shift of maximum intensity away from the primary site, or

advanced or severe disease. In cases presenting late with diffuse

peritonitis, generalized pain may completely obscure the

precipitating event..

Mode of Onset and Progression of Pain

The mode of onset of pain reflects the nature and severity of the

inciting process. Onset may be explosive (within seconds), rapidly

progressive (within 1–2 hours), or gradual (over several hours).

Unheralded, excruciating generalized pain suggests an intra-

abdominal catastrophe such as a perforated viscus or rupture of an

aneurysm, ectopic pregnancy, or abscess. Accompanying systemic

signs (tachycardia, sweating, tachypnea, shock) soon supersede

the abdominal disturbances and underscore the need for prompt

resuscitation and laparotomy.

A less dramatic clinical picture is steady, mild pain becoming

intensely centered in a well-defined area within 1–2 hours. Any of

the above conditions may present in this manner, but this mode of

onset is more typical of acute cholecystitis, acute pancreatitis,

strangulated bowel, mesenteric infarction, renal or ureteral colic,

and high (proximal) small bowel obstruction.

Finally, some patients initially have slight—at times only vague—

abdominal discomfort that is fleetingly present diffusely

throughout the abdomen. It may be unclear whether these patients

even have an acute abdomen or whether the illness is likely to be a

matter for medical rather than surgical attention. Associated

gastrointestinal symptoms are infrequent at first, and systemic

symptoms are absent. Eventually, the pain and abdominal findings

become more pronounced and steady and are localized to a

smaller area. This pattern may reflect a slowly developing

condition or the body's defensive efforts to cordon off an acute

process. This broad category includes acute appendicitis

(especially retrocecal or retroileal), incarcerated hernias, low

(distal) small bowel and large bowel obstructions, uncomplicated

peptic ulcer disease, walled-off (often malignant) visceral

perforations, some genitourinary and gynecologic conditions, and

milder forms of the rapid-onset group mentioned in the first

paragraph.

Character of Pain

The nature, severity, and periodicity of pain provide useful clues

to the underlying cause (Figure). Steady pain is most common.

Sharp superficial constant pain due to severe peritoneal irritation

is typical of perforated ulcer or a ruptured appendix, ovarian cyst,

or ectopic pregnancy. The gripping, mounting pain of small bowel

obstruction (and occasionally early pancreatitis) is usually

intermittent, vague, deep-seated, and crescendo at first but soon

becomes sharper, unremitting, and better localized. Unlike the

disquieting but bearable pain associated with bowel obstruction,

pain caused by lesions occluding smaller conduits (bile ducts,

uterine tubes, and ureters) rapidly becomes unbearably intense.

Pain is appropriately referred to as colic if there are pain-free

intervals that reflect intermittent smooth muscle contractions, as in

ureteral colic. .. The "aching discomfort" of ulcer pain, the

"stabbing, breathtaking" pain of acute pancreatitis and mesenteric

infarction, and the "searing" pain of ruptured aortic aneurysm

remain apt descriptions. Despite the use of such descriptive terms,

the quality of visceral pain is not a reliable clue to its cause.

Other Symptoms Associated with Abdominal Pain

Anorexia, nausea and vomiting, constipation, or diarrhea often

accompanies abdominal pain, but since these are nonspecific

symptoms, they do not have much diagnostic value.

Vomiting

When sufficiently stimulated by secondary visceral afferent fibers,

the medullary vomiting centers activate efferent fibers to induce

reflex vomiting. Hence, pain in the acute surgical abdomen

usually precedes vomiting, whereas the reverse holds true in

medical conditions. Vomiting is a prominent symptom in upper

gastrointestinal diseases such as acute gastritis, and acute

pancreatitis. Severe, uncontrollable retching provides temporary

pain relief in moderate attacks of pancreatitis. The absence of bile

in the vomitus is a feature of pyloric stenosis. Where associated

findings suggest bowel obstruction, the onset and character of

vomiting may indicate the level of the lesion. Recurrent vomiting

of bile-stained fluid is a typical early sign of proximal small bowel

obstruction. In distal small or large bowel obstruction, prolonged

nausea precedes vomiting, which may become feculent in late

cases.. Although vomiting may present in either acute appendicitis

or nonspecific abdominal pain, coexisting nausea and anorexia are

more suggestive of the former condition.

Constipation Reflex ileus is often induced by visceral afferent

fibers stimulating efferent fibers of the sympathetic autonomic

nervous system (splanchnic nerves) to reduce intestinal peristalsis.

Hence, paralytic ileus undermines the value of constipation in the

differential diagnosis of an acute abdomen. Constipation itself is

hardly an absolute indicator of intestinal obstruction. However,

obstipation (the absence of passage of both stool and flatus)

strongly suggests mechanical bowel obstruction if there is

progressive painful abdominal distention or repeated vomiting.

Diarrhea Copious watery diarrhea is characteristic of

gastroenteritis and other medical causes of an acute abdomen.

Blood-stained diarrhea suggests ulcerative colitis, Crohn disease,

or bacillary or amebic dysentery. It is also common with ischemic

colitis but often absent in intestinal infarction due to superior

mesenteric artery occlusion.

Other Relevant Aspects of the History

Gynecologic History The menstrual history is crucial to the

diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy, mittelschmerz (due to a ruptured

ovarian follicle), and endometriosis. A history of vaginal

discharge or dysmenorrhea may denote pelvic inflammatory

disease.

Drug History Anticoagulants have been implicated in

retroperitoneal and intramural duodenal and jejunal hematomas;

oral contraceptives have been implicated in the formation of

benign hepatic adenomas and in mesenteric venous infarction.

Corticosteroids, in particular, may mask the clinical signs of even

advanced peritonitis.

Family History :Family history often provides the best

information about medical causes of an acute abdomen.

.

Operation History Any history of a previous abdominal, groin,

vascular, or thoracic operation may be relevant to the current

illness. Particular attention to the mode of operation (laparoscopic,

open, endovascular) and any anatomic reconstructions may clarify

aspects of the current complaint

Physical Examination

The tendency to concentrate on the abdomen should be resisted in

favor of a methodical and complete general physical examination.

A systematic approach to the abdominal examination noticing

specific signs that confirm or rule out differential diagnostic

possibilities

General observation: General observation affords a fairly

reliable indication of the severity of the clinical situation. The

writhing of patients with visceral pain (eg, intestinal or ureteral

colic) contrasts with the rigidly motionless bearing of those with

parietal pain (eg, acute appendicitis, generalized peritonitis).

Diminished responsiveness or an altered sensorium often precedes

imminent cardiopulmonary collapse.

Systemic signs: Systemic signs usually accompany rapidly

progressive or advanced disorders associated with an acute

abdomen. Extreme pallor, hypothermia, tachycardia, tachypnea,

and sweating suggest major intra-abdominal hemorrhage (eg,

ruptured aortic aneurysm or tubal pregnancy). Given such

findings, one must proceed rapidly with the subsequent

examination and tests in order to exclude extra-abdominal causes.

Fever: Constant low-grade fever is common in inflammatory

conditions such as diverticulitis, acute cholecystitis, and

appendicitis. High fever with lower abdominal tenderness in a

young woman without signs of systemic illness suggests acute

salpingitis. Disorientation or extreme lethargy combined with a

very high fever (> 39 °C) or swinging fever or with chills and

rigors signifies impending septic shock. This is most often due to

advanced peritonitis, acute cholangitis, or pyelonephritis.

However, fever is often mild or absent in elderly, chronically ill,

or immunosuppressed patients with a serious acute abdomen.

Inguinal and femoral rings; male genitalia: The inguinal and

femoral rings in both sexes and the genitalia in male patients

should be examined next.

Rectal examination: A rectal examination should be performed in

most patients with an acute abdomen. Diffuse tenderness is

nonspecific, but right-sided rectal tenderness accompanied by

lower abdominal rebound tenderness is indicative of peritoneal

irritation due to pelvic appendicitis or abscess. Other useful

findings include a rectal tumor, blood-stained stool, or occult

blood (detected by guaiac testing

Pelvic examination: An acute abdomen is incorrectly diagnosed

more often in women than in men, particularly in younger age

groups. A pelvic examination is vital in women with a vaginal

discharge, dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia, or left lower quadrant

pain..

Investigative Studies

The history and physical examination by themselves provide the

diagnosis in two thirds of cases of an acute abdomen.

Supplementary laboratory and radiologic examinations are

indispensable for diagnosis of many surgical conditions, for

exclusion of medical causes ordinarily not treated by operation,

and for assistance

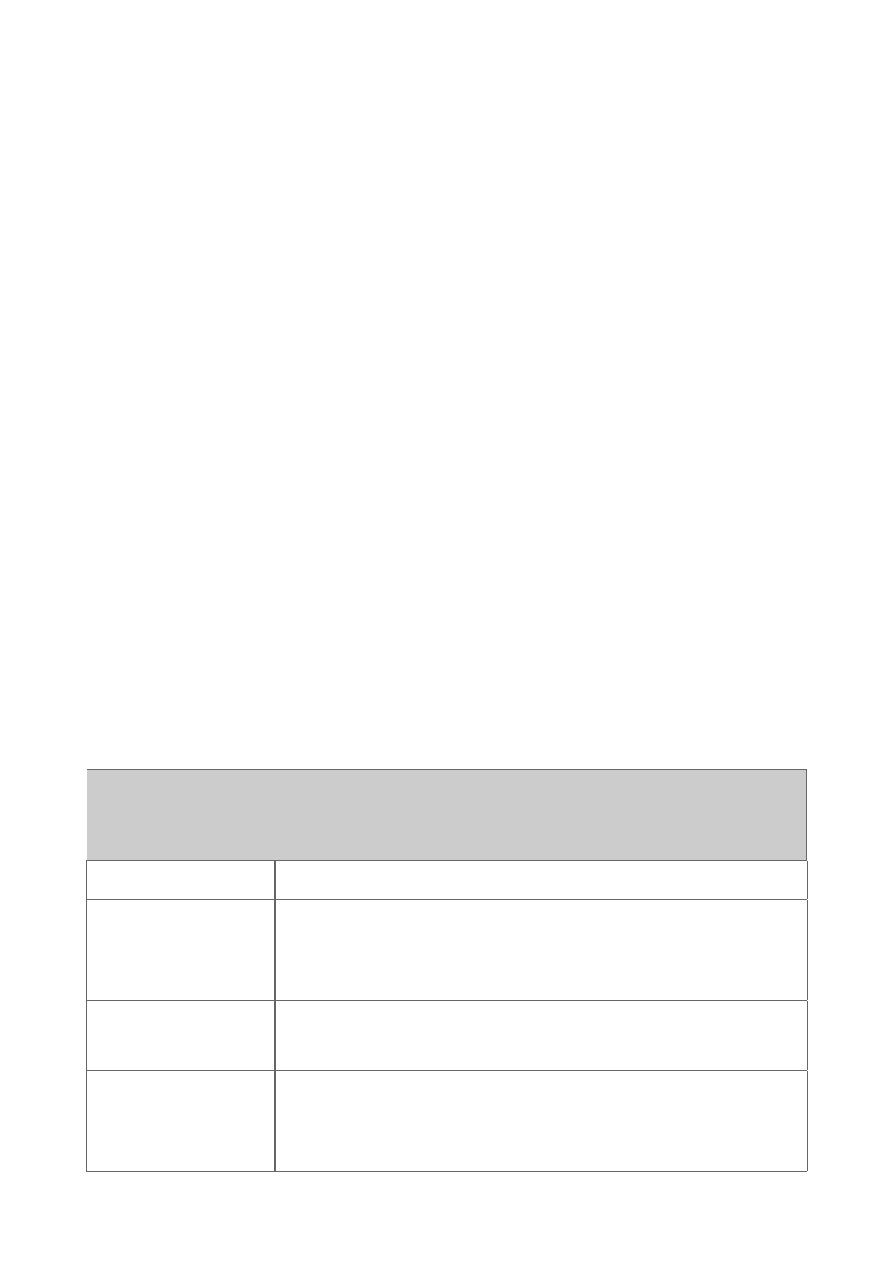

Physical Findings in Various Causes of Acute Abdomen.

Condition

Helpful Signs

Perforated

viscus

Scaphoid, tense abdomen; diminished bowel

sounds (late); loss of liver dullness; guarding or

rigidity.

Peritonitis

Motionless; absent bowel sounds (late); cough

and rebound tenderness; guarding or rigidity.

Inflamed mass

or abscess

Tender mass (abdominal, rectal, or pelvic);

bump tenderness; special signs (Murphy, psoas,

or obturator).

Intestinal

obstruction

Distention; visible peristalsis (late);

hyperperistalsis (early) or quiet abdomen (late);

diffuse pain without rebound tenderness; hernia

or rectal mass (some).

Paralytic ileus

Distention; minimal bowel sounds; no localized

tenderness.

Ischemic or

strangulated

bowel

Not distended (until late); bowel sounds

variable; severe pain but little tenderness; rectal

bleeding (some).

Bleeding

Pallor, shock; distention; pulsatile (aneurysm)

or tender (eg, ectopic pregnancy) mass; rectal

bleeding (some).

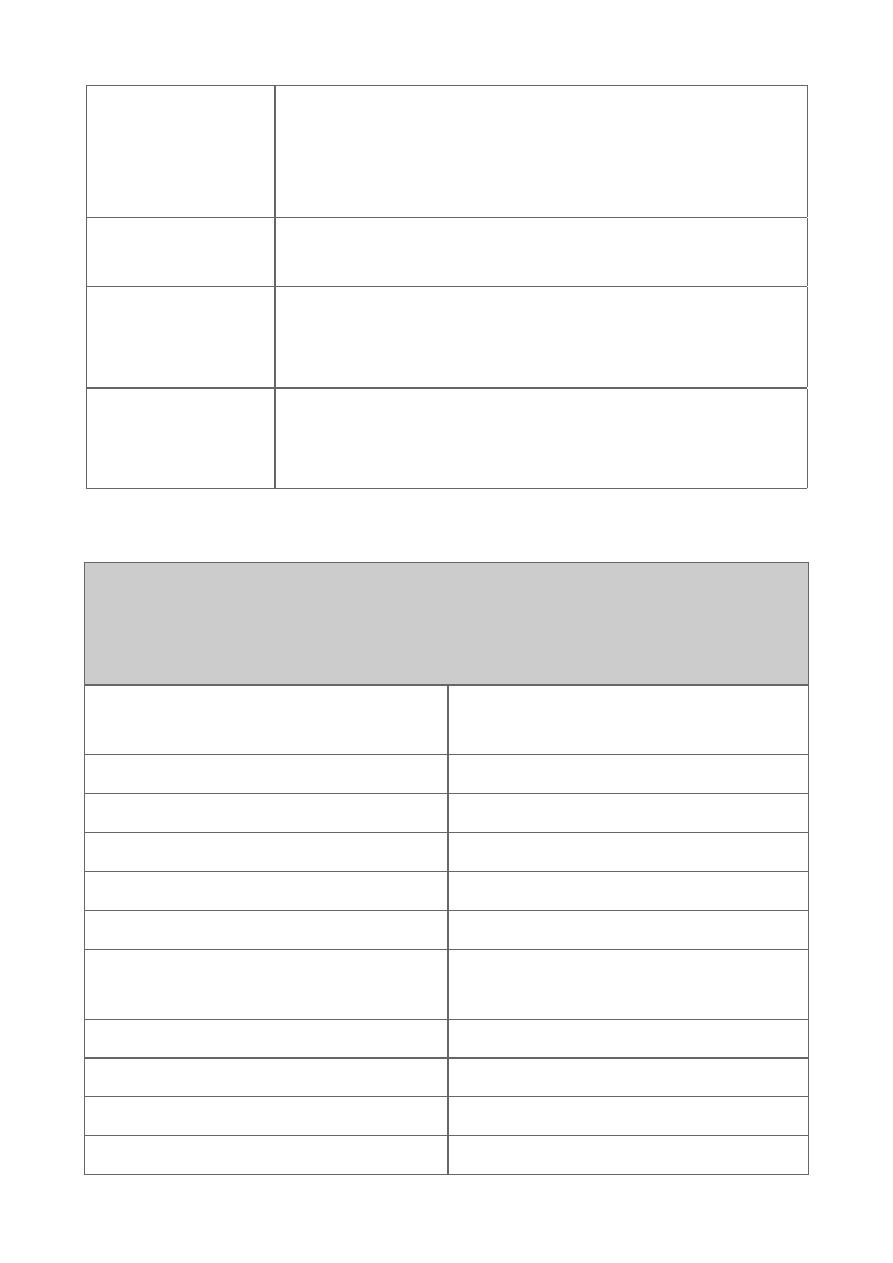

Medical Causes of an Acute Abdomen for which Surgery Is Not

Indicated.

Endocrine and metabolic

disorders

Infections and inflammatory

disorders

Uremia

Tabes dorsalis

Diabetic crisis

Herpes zoster

Addisonian crisis

Acute rheumatic fever

Acute intermittent porphyria

Henoch-Schönlein purpura

Acute hyperlipoproteinemia

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Hereditary Mediterranean

fever

Polyarteritis nodosa

Hematologic disorders

Referred pain

Sickle cell crisis

Thoracic region

Acute leukemia

Myocardial infarction

Other dyscrasias

Acute pericarditis

Toxins and drugs

Pneumonia

Lead and other heavy metal

poisoning

Pleurisy

Narcotic withdrawal

Pulmonary embolus

Black widow spider poisoning Pneumothorax

Empyema

Hip and back

Indications for Urgent Operation in Patients with an Acute

Abdomen.

Physical findings

Involuntary guarding or rigidity, especially if spreading

Increasing or severe localized tenderness

Tense or progressive distention

Tender abdominal or rectal mass with high fever or hypotension

Rectal bleeding with shock or acidosis

Equivocal abdominal findings along with septicemia (high

fever, marked or rising leukocytosis, mental changes, or

increasing glucose intolerance in a diabetic patient)

Bleeding (unexplained shock or acidosis, falling hematocrit)

Suspected ischemia (acidosis, fever, tachycardia)

Deterioration on conservative treatment

Radiologic findings

Pneumoperitoneum

Gross or progressive bowel distention

Free extravasation of contrast material

Space-occupying lesion on scan, with fever

Mesenteric occlusion on angiography

.