1

Lec. 2 Dr.Abeer Zwain

CHRONIC NONSPECIFIC GINGIVITIS

A type of gingivitis commonly seen during the preteenage and teenage years is often referred

to as chronic nonspecific gingivitis. The chronic gingival inflammation may be localized to the

anterior region, or it may be more generalized. Although the condition is rarely painful,

the fiery

red gingival lesion is not accompanied by enlarged interdental labial papillae or closely

associated with local irritants. The gingivitis showed little improvement after aprophylactic

treatment, it may persist for long periods without much improvement.

The cause of gingivitis is complex and is considered to be based on a multitude of local and

systemic factors. Possible factors could be:

* hormonal imbalance.

* Inadequate oral hygiene, which allows food impaction and the accumulation of materia alba

and bacterial plaque, is undoubtedly the major cause of this chronic type of gingivitis.

*They discovered that the chronic gingivitis group had a larger percentage of AB blood types

and a smaller percentage of 0 blood type than the control group.

*Insufficient quantities of fruits and vegetables in the diet, leading to a subclinical vitamin

deficiency, may be an important predisposing factor. An improved dietary intake of vitamins

and the use of multiple-vitamin supplements will improve the gingival condition in many

children.

*Malocclusion, which prevents adequate function, and crowded teeth, which make oral hygiene

and plaque removal more difficult, are also important predisposing factors in gingivitis.

* Carious lesions with irritating sharp margins, as well as faulty restorations with overhanging

margins (both of which cause food accumulation), also favor the development of the chronic

type of gingivitis.

* mouth breathing is often responsible for the development of

the chronic hyperplastic form of

gingivitis, particularly in the maxillary arch.

All these factors should be considered contributory to chronic nonspecific gingivitis and

should be corrected in the treatment of the condition.

GINGIVAL DISEASES MODIFIED

BY SYSTEMIC FACTORS

GINGIVAL DISEASES ASSOCIATED

WITH THE ENDOCRINE SYSTEM

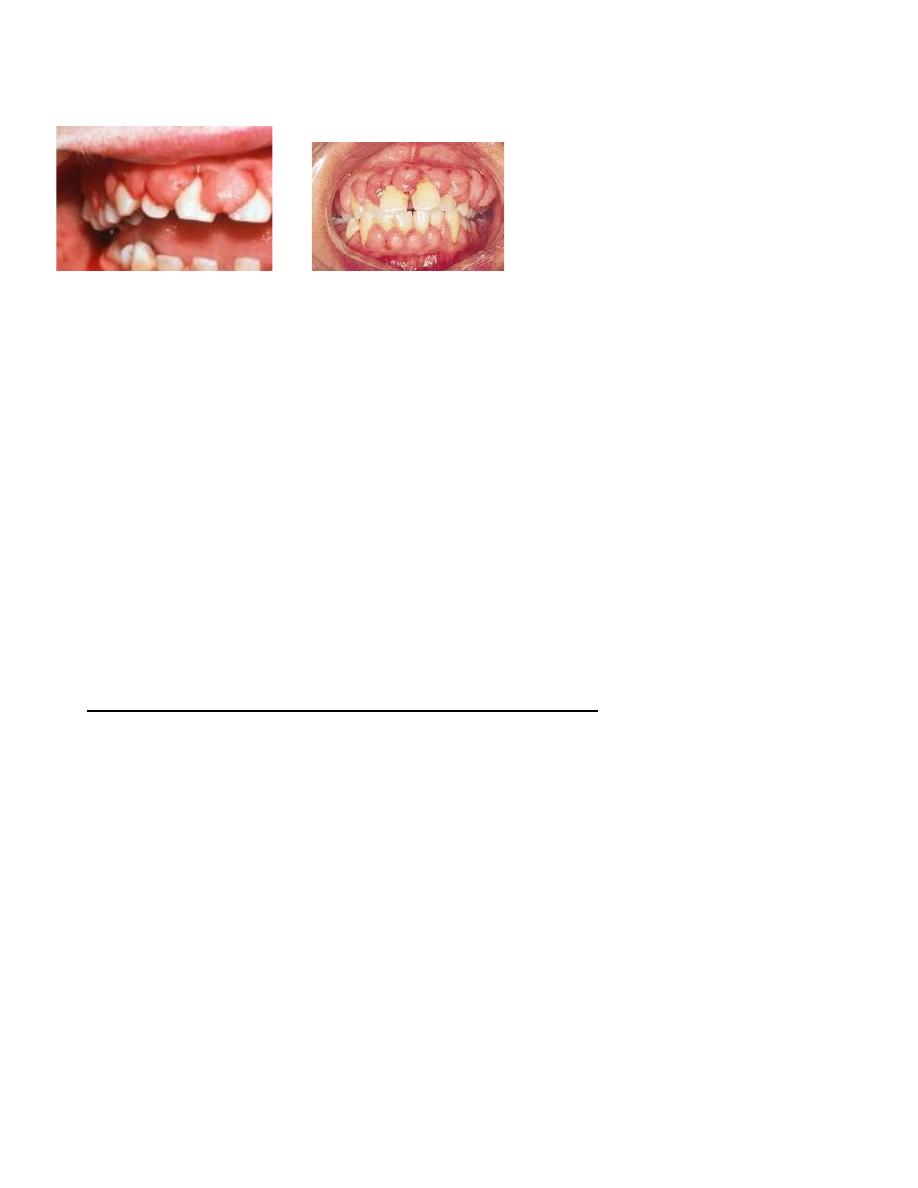

Puberty gingivitis is a distinctive type of gingivitis that occasionally develops in children in

the prepubertal and pubertal period.

The gingival enlargement is marginal in distribution and, in

the presence of local irritants, was characterized by prominent bulbous interproximal papillae

far greater than gingival enlargements associated with local factors.

2

Treatment of puberty gingivitis should be directed toward improved oral hygiene, removal of

all local irritants, restoration of carious teeth, and dietary changes necessary to ensure an

adequate nutritional status. Severe cases of hyperplastic gingivitis that do not respond to local

or systemic therapy should be treated by gingivoplasty.

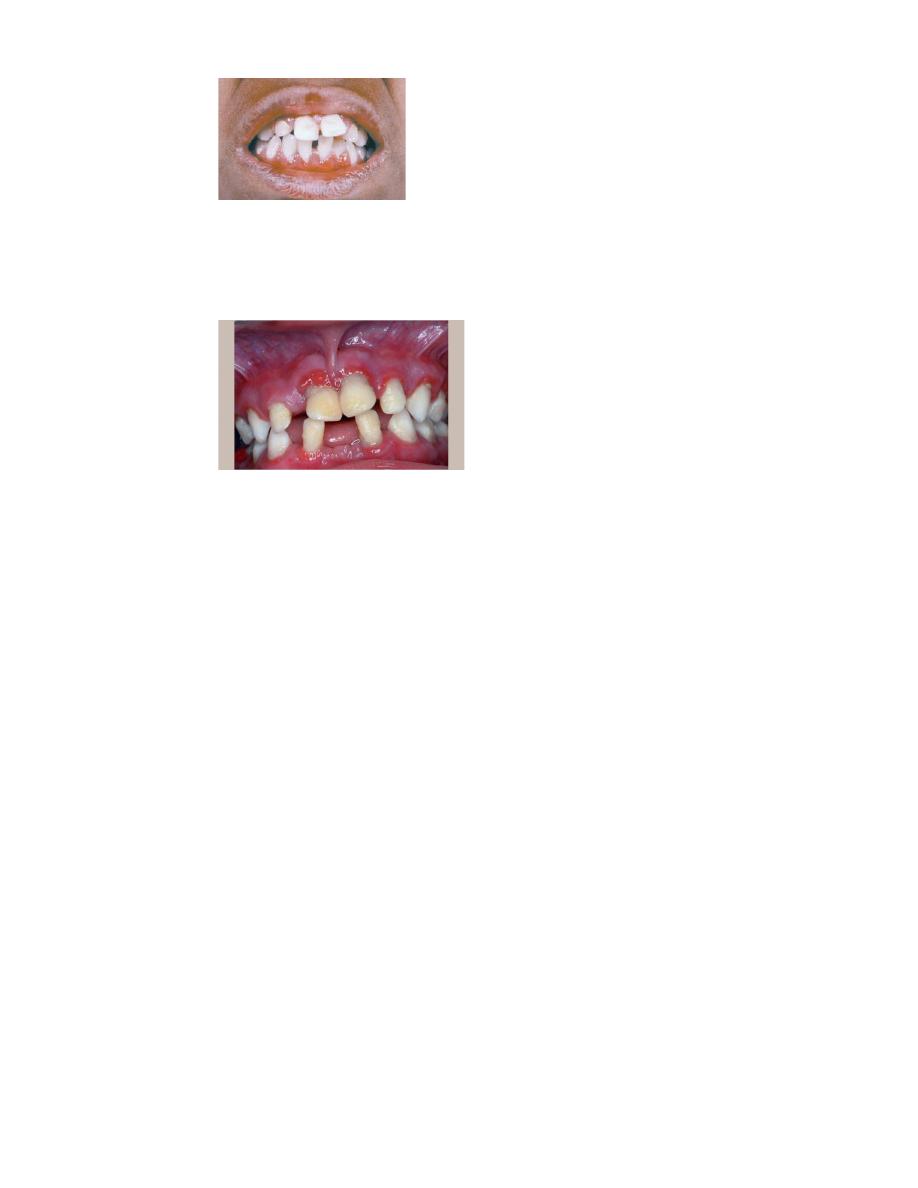

GINGIVAL LESIONS OF GENETIC ORIGIN Hereditary

gingival fibromatosis (HGF) is characterized by a slow, progressive, benign enlargement of

the gingivae. Genetic and pharmacologically induced forms of gingival enlargement are known.

The gingival tissues appear normal at birth but begin to enlarge with the eruption of the primary

teeth. Although mild cases are observed, the gingival tissues usually continue to enlarge with

eruption of the permanent teeth until the tissues essentially cover the clinical crowns of the

teeth. The dense fibrous tissue often causes displacement of the teeth and malocclusion. The

condition is not painful until the tissue enlarges to the extent that it partially covers the

occlusalsurface of the molars and becomes traumatized during mastication.

Surgical removal of the hyperplastic tissue achieves a more favorable oral and facial

appearance. However, hyperplasia can recur within a few months after the surgical procedure

and can return to the original condition within a few years.

PHENYTOIN-INDUCED GINGIVAL OVERGROWTH( PIGO)

Phenytoin (Dilantin, or diphenylhydantoin), a major anticonvulsant agent used in the

treatment of epilepsy. Varying degrees of gingival hyperplasia, one of the most common side

effects of phenytoin therapy. Most investigators agree on the existence of a close relationship

between oral hygiene and PIGO. PIGO can be decreased or prevented by scrupulous oral

3

hygiene and dental prophylaxis. The relationship between plaque, local irritants, and PIGO is

also supported by the observation that patients without teeth almost never develop PIGO.

PIGO, when it does develop, begins to appear as early as 2 to 3 weeks after initiation of

phenytoin therapy and peaks at 18 to 24 months.

painless enlargement of the interproximal gingiva

The buccal and anterior segments are more often affected

As the interdental lobulations grow, clefting becomes apparent at the midline of the tooth

In some cases, the entire occlusal surface of the teeth becomes covered.

PIGO may impose problems of

esthetics,

difficulty in mastication,

speech impairment,

delayed tooth eruption, tissue trauma, and secondary inflammation leading to periodontal

disease.

dental treatment based on clinical oral signs and symptoms

Patients with mild PIGO (i.e., less than one third of the clinical crown is covered) require

daily meticulous oral hygiene and more frequent dental care.

For patients with moderate PIGO (i.e., one third to two thirds of the clinical crown is

covered)

meticulous oral home care

and the judicious use of an irrigating device may be needed.

In addition, prophylaxis and topical stannous fluoride application is

recommended.

If there has been no change, consultation with the patient's physician concerning

the possibility of using a different anticonvulsant drug may be helpful.

If no improvement occurs, surgical removal of the overgrowth

may be recommended.

For patients with severe PIGO (i.e., more than two thirds of the tooth is covered) who do

not respond to the previously mentioned therapeutic regimens, surgical removal is

necessary.

Gradual recurrences of the fibrous tissue usually follow the treatment.

4

There is success in controlling the gingival overgrowth with positive-pressure appliances.

Other drugs that have been reported to induce gingival overgrowth in some patients include

cyclosporin, calcium channel blockers, valproic acid, and phenobarbital. As with all disorders

affecting periodontal tissues, maintaining excellent oral hygiene is the primary key to successful

therapy.

ASCORBIC ACID DEFICIENCY

GINGIVITIS

Scorbutic gingivitis is associated with vitamin C deficiency and differs from the type of

gingivitis related to poor oral hygiene.

The involvement is usually limited to the marginal tissues and papillae.

The child with scorbutic gingivitis may complain of severe pain,

and spontaneous hemorrhage will be evident.

Complete dental care, improved oral hygiene, and supplementation with vitamin C(the daily

administration of 250 to 500 mg of ascorbic acid ) and other watersoluble vitamins will greatly

improve the gingival condition.

PERIODONTAL DISEASES

IN CHILDREN

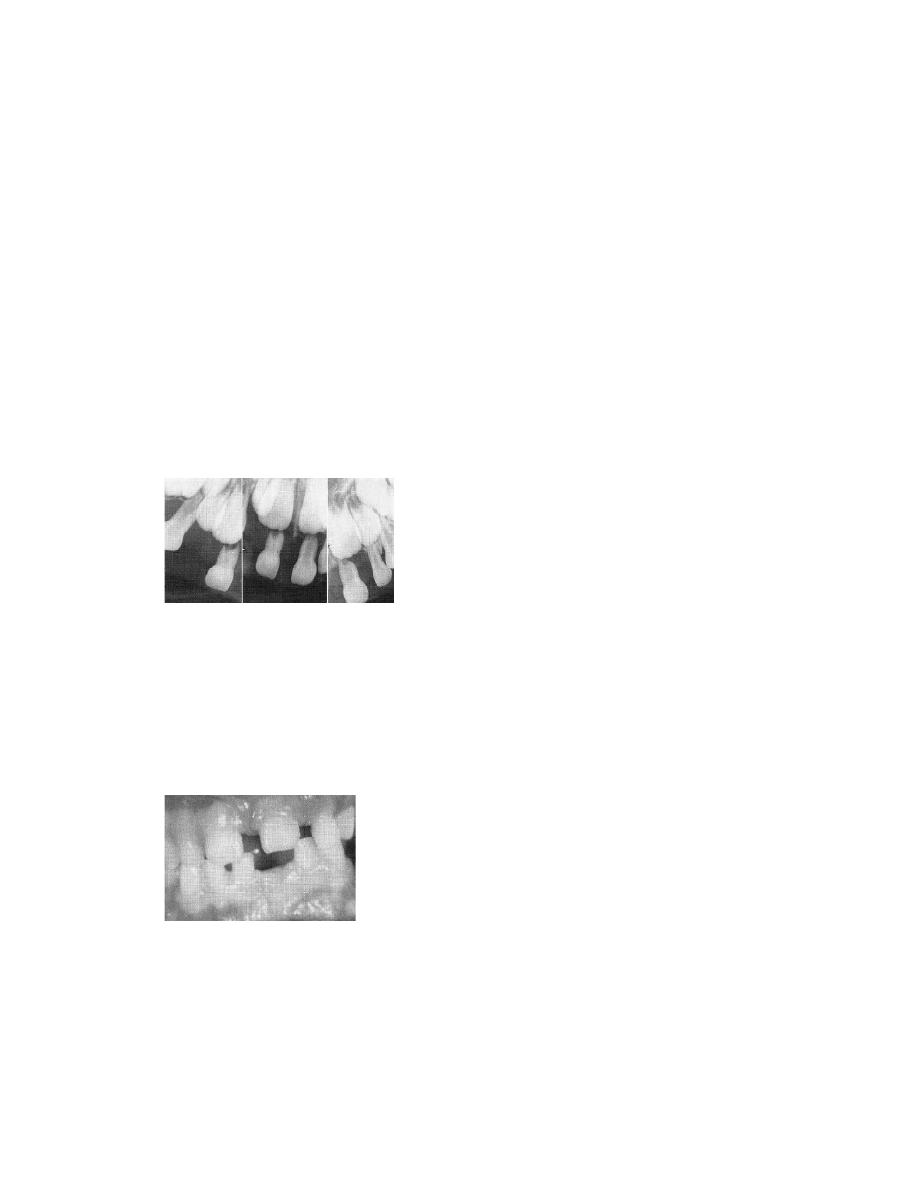

Periodontitis, an inflammatory disease of the gingiva and deeper tissues of the

periodontium, is characterized by pocket formation and destruction of the supporting alveolar

bone. Bone loss in children can be detected in bite-wing radiographs by comparing the height of

the alveolar bone to the cementoenamel junction.

Distances between 2 and 3 mm can be defined as questionable bone loss and distances

greater than 3 mm indicate definite bone loss.

5

AGGRESSIVE PERIODONTITIS

(EARLY-ONSET PERIODONTITIS)

EOP is used as a generic term to describe a heterogeneous group of periodontal disease

occurring in young individuals who are otherwise healthy. EOP can be viewed as :

(1) a localized form (localized juvenile periodontitis [LJP]),

(2) a generalized form (generalized juvenile periodontitis [ GJPI)

the prevalence of aggressive periodontitis in adolescent schoolchildren in the United States is

more in African Americans than in whites and more in boys than in girls.

Aggressive periodontitis of the primary dentition can occur in a localized form but is

usually seen in the generalized form.

LAP is localized attachment loss and alveolar bone loss only in the primary

dentition in an otherwise healthy child.

The exact time of onset is unknown, but it appears to arise around or before 4 years

of age, when the bone loss is usually seen on radiographs around the primary

molars and/or incisors.

Abnormal probing depths with minor gingival inflammation, rapid bone loss, and

minimal to various amounts of plaque have been demonstrated at the affected sites

of the child’s dentition.

Abnormalities in host defenses (e.g., leukocyte chemotaxis), extensive proximal

caries facilitating plaque retention and bone loss, and a family history of

periodontitis have been associated with LAP in children.

As the disease progresses, the child’s periodontium shows signs of gingival

inflammation, with gingival clefts and localized ulceration of the gingival margin.

GENERALIZED AGGRESSIVE PERIODONTITIS

The onset of GAP is during or soon after the eruption of the primary teeth.

It results in severe gingival inflammation and generalized attachment loss,

tooth mobility, and rapid alveolar bone loss with premature exfoliation of

the teeth.

The gingival tissue may initially demonstrate only minor inflammation with

plaque accumulation at a minimum.

6

It often affects the entire dentition.

Alveolar bone destruction proceeds rapidly, and the primary teeth may be

lost by 3 years of age.

Because of its wide distribution and rapid rate of alveolar bone destruction,

the GAP was previously known as generalized juvenile periodontitis, severe

periodontitis, and rapidly progressive periodontitis.

Chronic cases display the presence of clefting and pronounced recession

with associated acute inflammation.

Affected teeth harbor more nonmotile, facultative, anaerobic, gram-negative

rods (especially Porphyromonas gingivalis) in GAP than in LAP.

Microorganisms predominating in the gingival pockets include

Aggregatibacter

actinomycetemcomitans

(Aa),

Porphyromonas

(Bacteroides) gingivalis (Pg), Bacteroides melaninogenicus, Prevotella

intermedia, Capnocytophaga sputigena, and Fusobacterium nucleatum.

the major periodontal pathogens are transmitted among family members.

The past medical history of the child often reveals a history of recurrent

infections (e.g., otitis media, skin infections, upper respiratory tract

infections).

LAP and GAP are distinctly different radiographically and clinically.

Neutrophils in GAP patients have suppressed.

Individuals with GAP exhibit marked periodontal inflammation and have

heavy accumulations of plaque and calculus. Testing may reveal a high

prevalence of leukocyte adherence abnormalities and an impaired host

response to bacterial infections.