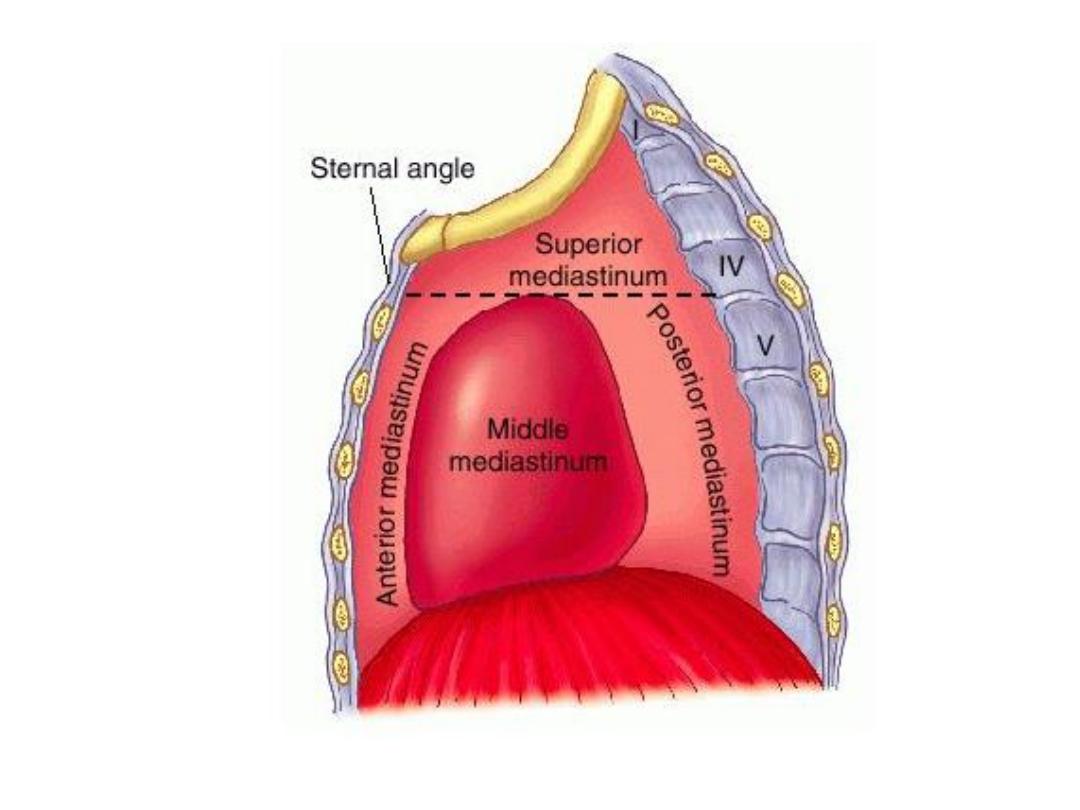

• Mediastinum : The mediastinum is divided into anterior, middle and

• posterior divisions for descriptive purposes. This can be demonstrated on a

lateral CXR , but is usually performed with CT.

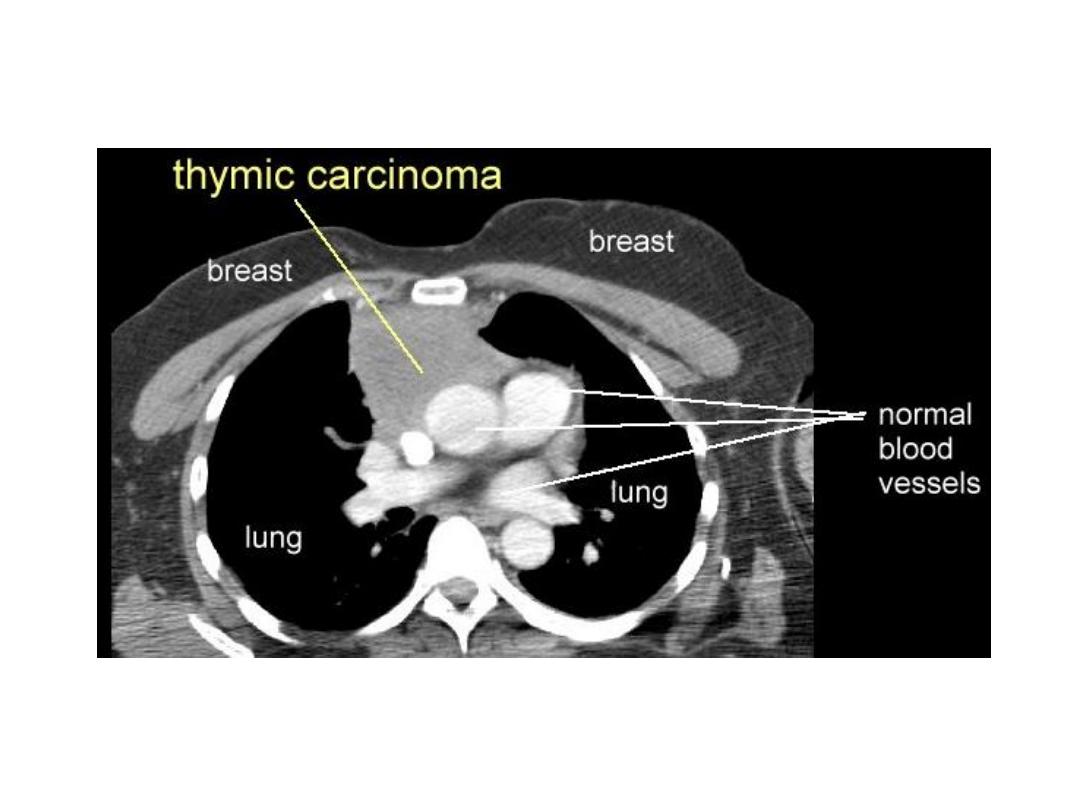

• CT and MRI of normal mediastinum: Computed tomography is the standard

method for imaging the mediastinum. MRI is used only occasionally. The cross

sectional display and the ability to distinguish between fat, various soft tissues

and blood vessels are major advantages of both techniques.

• • The mediastinum is composed predominantly of blood vessels. Visualization

and differentiation from other soft tissue structures is aided with the use of

intravenous contrast medium. At MRI, the larger vessels are readily seen

• without contrast agent.

• • The only other normal structures of appreciable size are the thymus,

oesophagus, trachea and bronchi.

• • Normal lymph nodes are small, usually less than 6 mm in diameter (maximum

10 mm), and many are not visible.

• • The mediastinal structures are surrounded by fat (low density on CT), this

enables visualization of other small soft tissue masses which are generally of

increased density.

• Mediastinal masses :

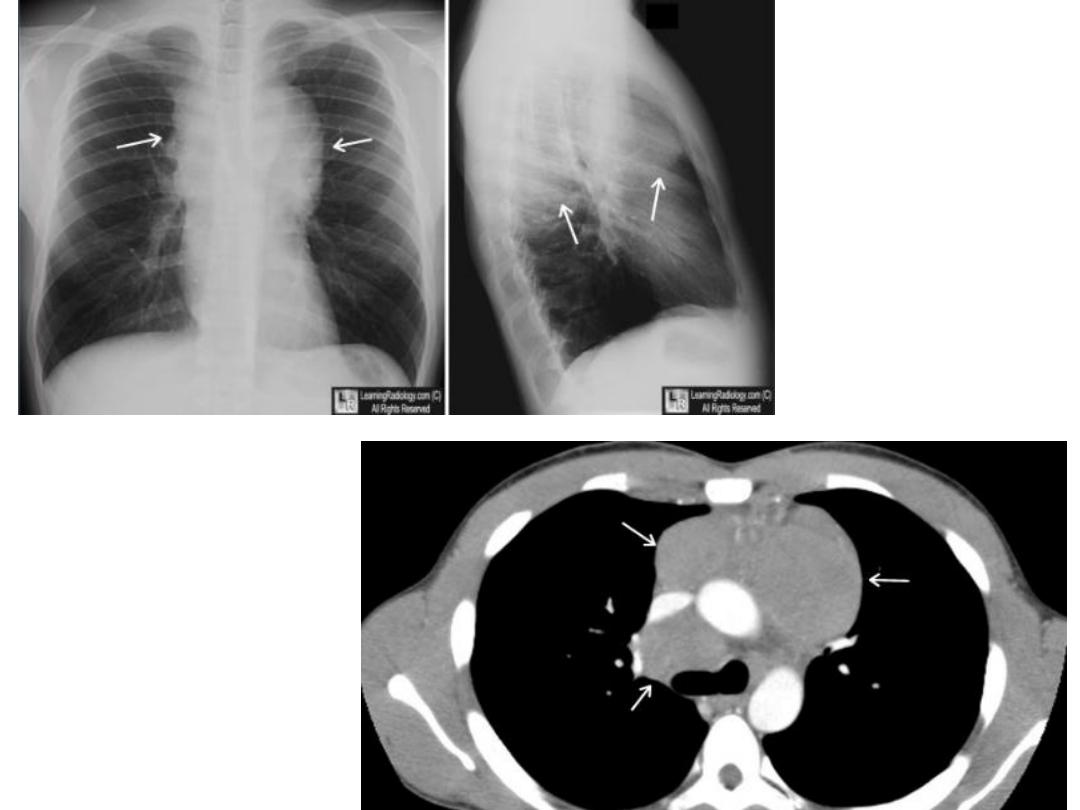

plain CXR :

• Intrathoracic thyroid masses (goitres) are the

most frequent cause of a superior mediastinal mass . The characteristic feature is that

the mass extends from the superior mediastinum into the neck and almost invariably

compresses or displaces the trachea.

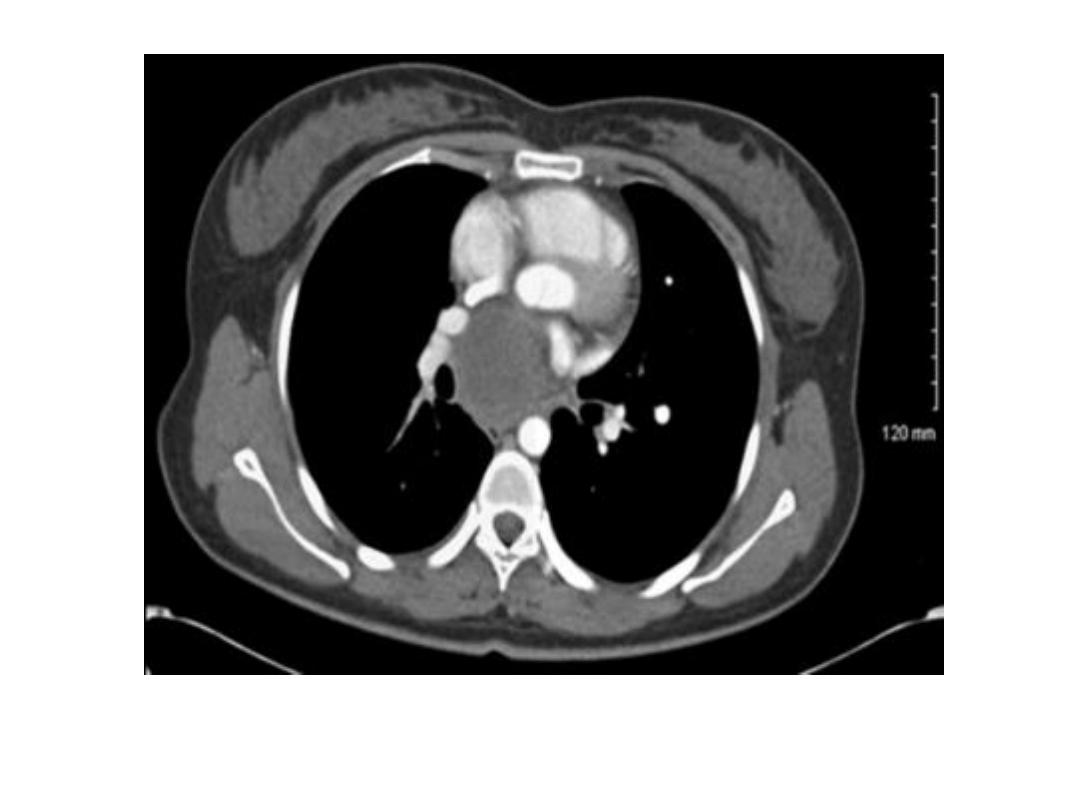

• A bronchogenic cyst is usually an incidental finding seen on CXR and confirmed on

CT.

• • Lymphadenopathy is the next most frequent cause of a mediastinal swelling.

Lymphadenopathy may occur in any of the three compartments and it is often

possible to diagnose enlarged lymph nodes from their lobulated outlines and the

multiple locations involved

• Neurogenic tumours are by far the commonest cause of posterior mediastinal masses.

Pressure deformity of the adjacent ribs and thoracic spine is often visible.

• Certain tumours, such as dermoid cysts and thymomas, are, for practical purposes,

confined to the anterior mediastinum.

• Calcification occurs in many conditions, but almost never in malignant

lymphadenopathy. Occasionally, the calcification is characteristic in appearance, e.g.

curvilinear in vascular wall calcification.

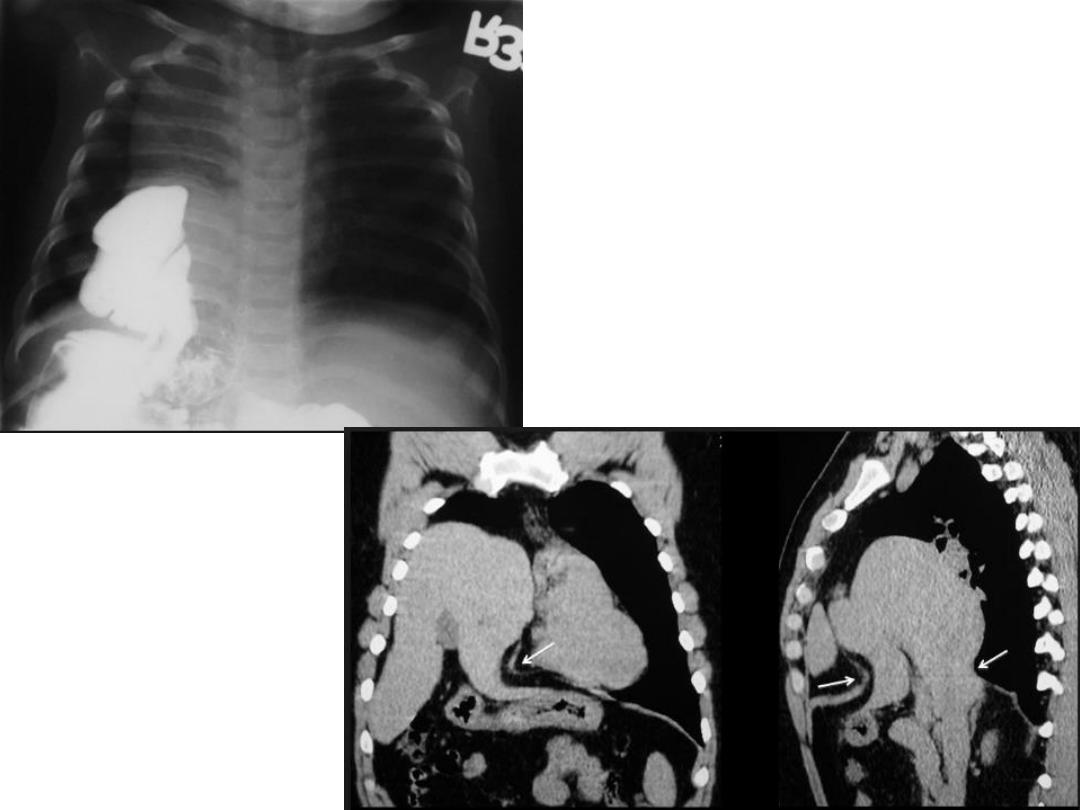

• A mediastinal mass due to a hiatus hernia is usually easy to diagnose on plain films

because it often contains air and may have a fluid level, best seen on the lateral view

• Masses in the right cardiophrenic angle anteriorly are usually all either large fat pads,

benign pericardial cysts, or hernias through the foramen of Morgagni .

•

CT scan :

Computed tomography provides much more information than

CXRs.

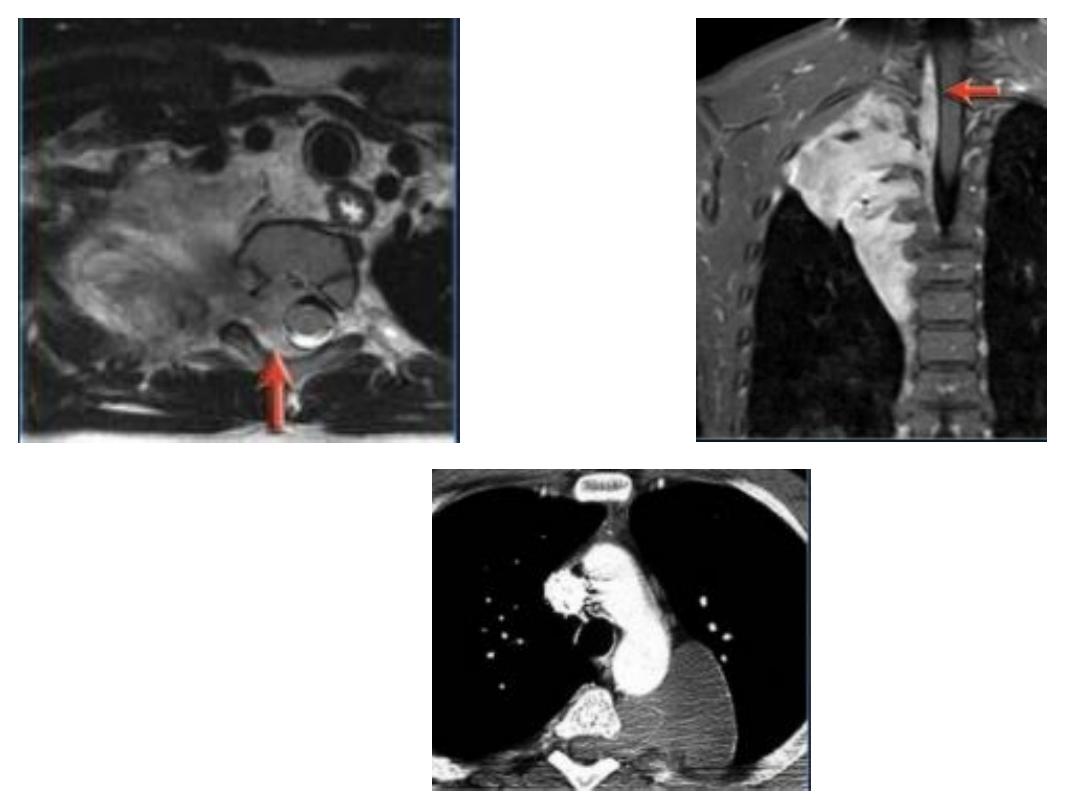

• MRI is used only in highly selected cases, 1- where CT contrast agents are

contraindicated or 2-demonstrating the relationship of a posterior mass to the

spinal canal

• There are two main advantages of CT.

1 -Abnormalities can be accurately localized: Knowledge of the precise shape,

position and size of a mediastinal mass frequently narrows the differential

diagnosis. For instance, contiguity of the mass with the thyroid in the neck

suggests a goitre , and multiple oval-shaped masses suggest

lymphadenopathy

2- Occasionally, the density of the abnormality reveals it nature:

• A- Fat can be recognized as such, which is useful in distinguishing large

cardiophrenic angle fat pads or unusual mediastinal fat collections from

tumours, e.g. in Cushing’s disease.

• Cystic teratomas (dermoid cysts) may contain recognizable fat.

• Because of its high iodine content, thyroid tissue is of higher attenuation than

muscle prior to contrast medium administration. After contrast, it enhances

brightly.

• Intravenous contrast enhancement permits delineation of aneurysms and

anomalous blood vessels from other masses.

• Calcification is readily seen. The presence of calcification in a mass is frequently

seen in benign conditions.

• Cysts containing clear fluid, e.g. pericardial cysts and some bronchogenic cysts

can be recognized by a CT number close to water (0 Hounsfield units).

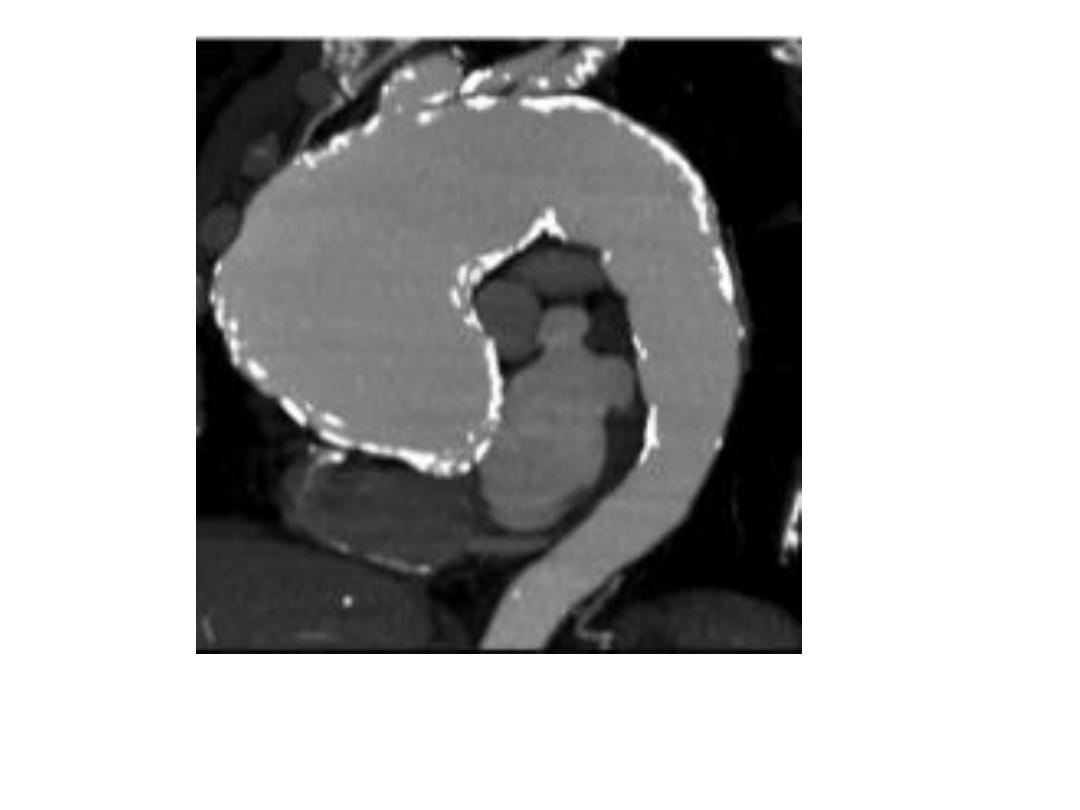

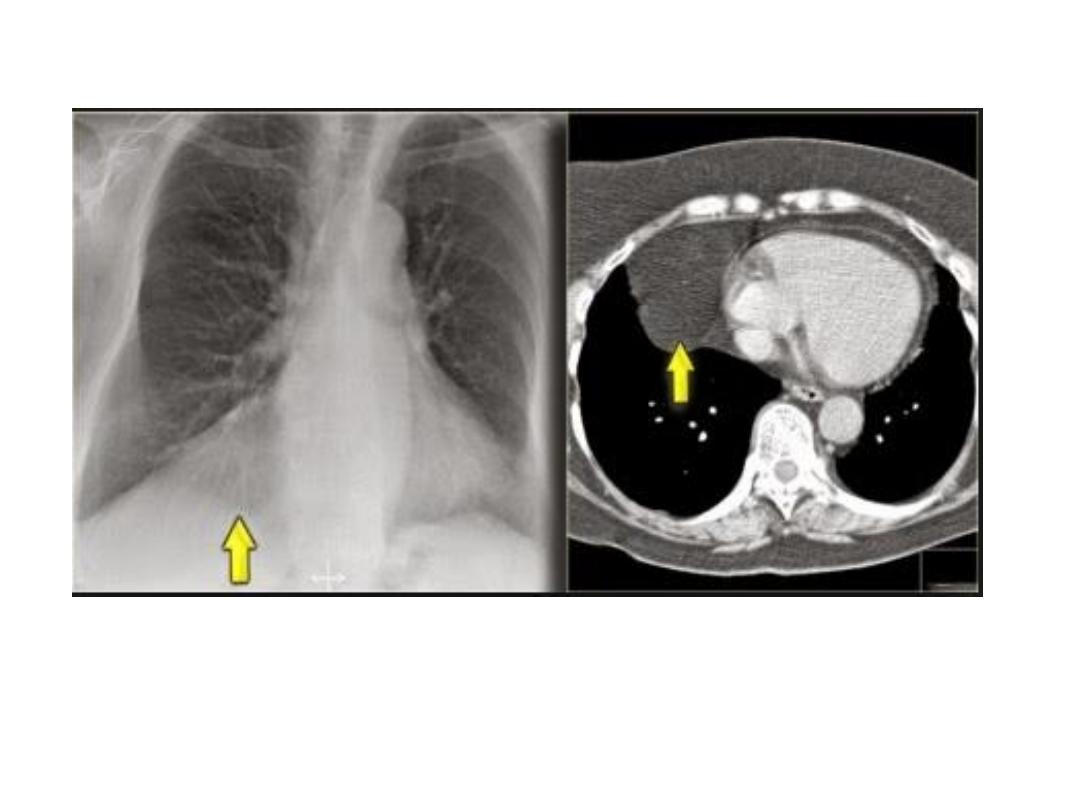

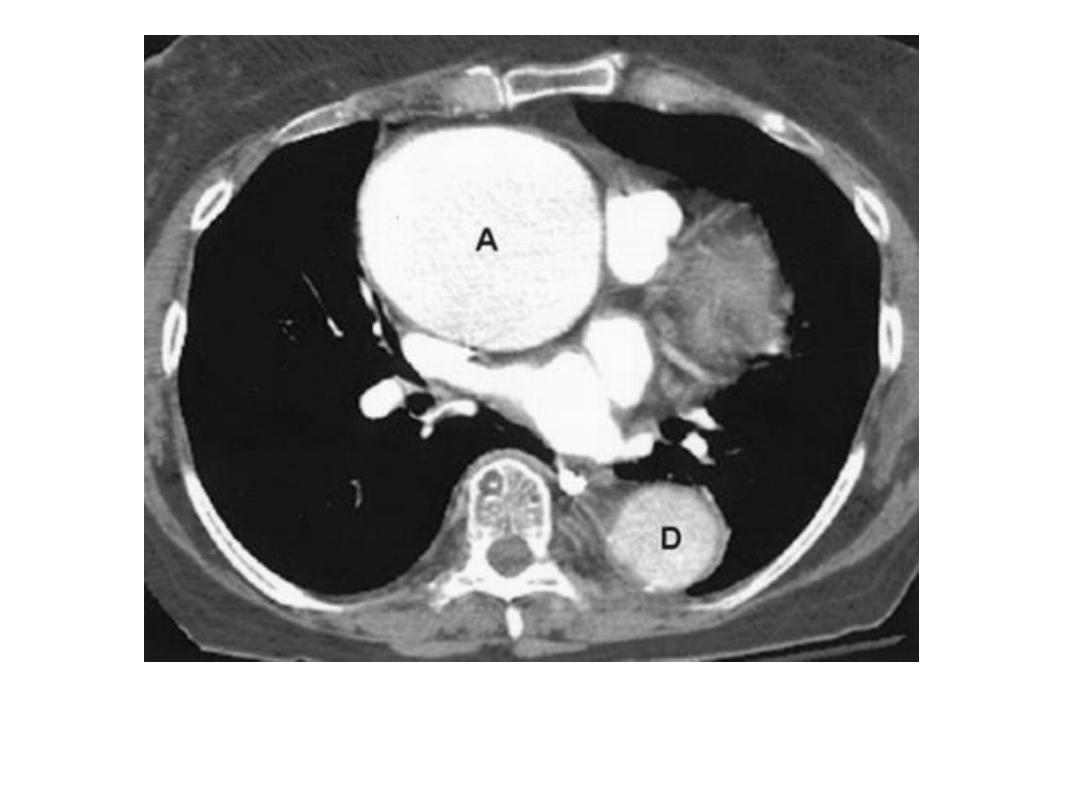

• Aortic aneurysm : Dilatation of the

ascending aorta may be due to aneurysm

formation or secondary to aortic regurgitation, aortic stenosis or systemic

hypertension.

• Substantial dilatation of the ascending aorta is needed before a bulge of the right

mediastinal border can be recognized.

• aortic unfolding is a commoner cause of a bulge of the right superior

mediastinum than ascending aortic aneurysm.

• The two common causes of aneurysm of the

descending aorta are atheroma and

aortic dissection.

•

A rarer cause is

previous trauma, usually following a severe deceleration

• injury.

• Descending aortic aneurysms are often visible on CXRs and atheromatous

aneurysms usually show calcification in their walls.

• Computed tomography with intravenous contrast enhancement, magnetic

resonance angiography (MRA) and/or echocardiography are very useful when

aortic aneurysms are assessed .

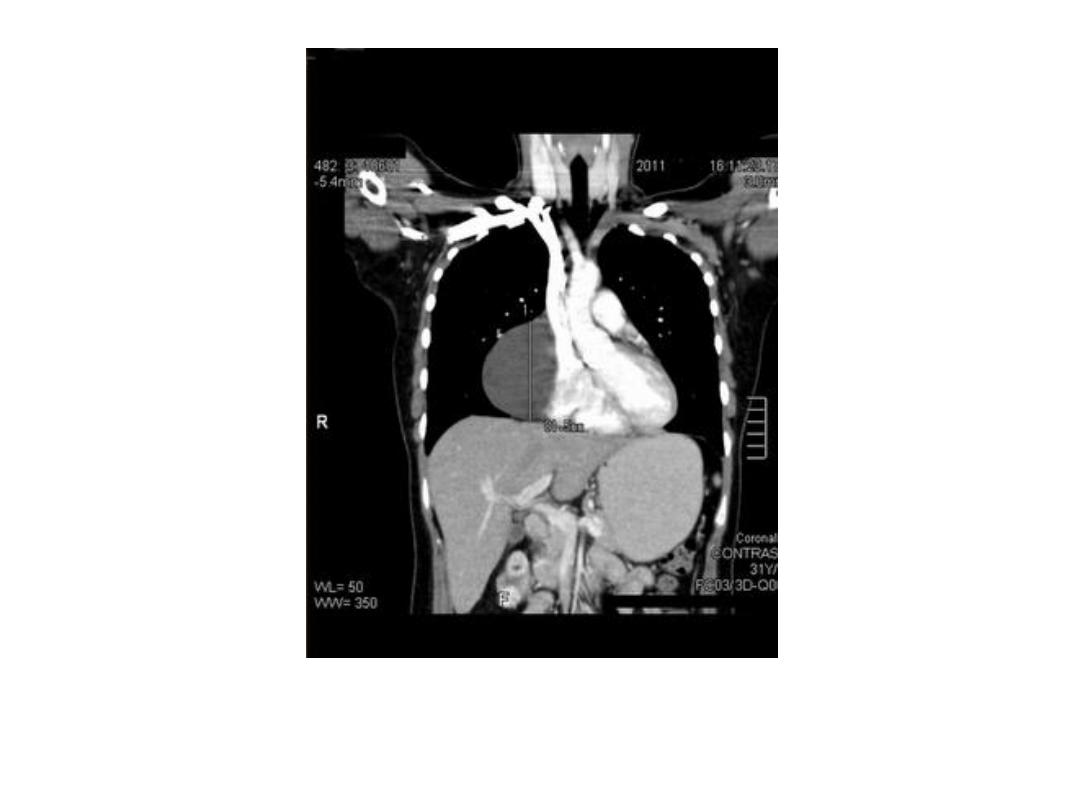

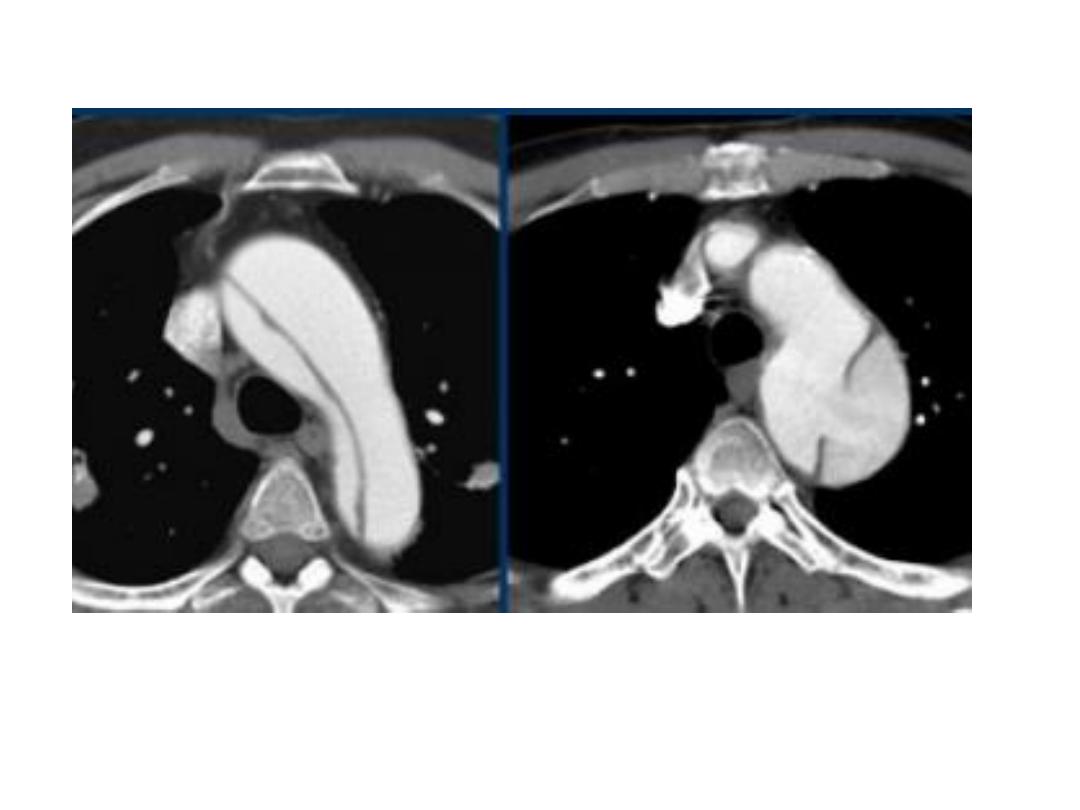

• It is important to know the extent of aortic dissections because those involving

the ascending aorta are treated surgically, while those confined to the

descending aorta are usually treated by an endovascular approach if

conservative management is not appropriate.

• Aortic dissections can be shown with CT (and MRI) and these non-invasive

techniques have, in practice, replaced aortography.

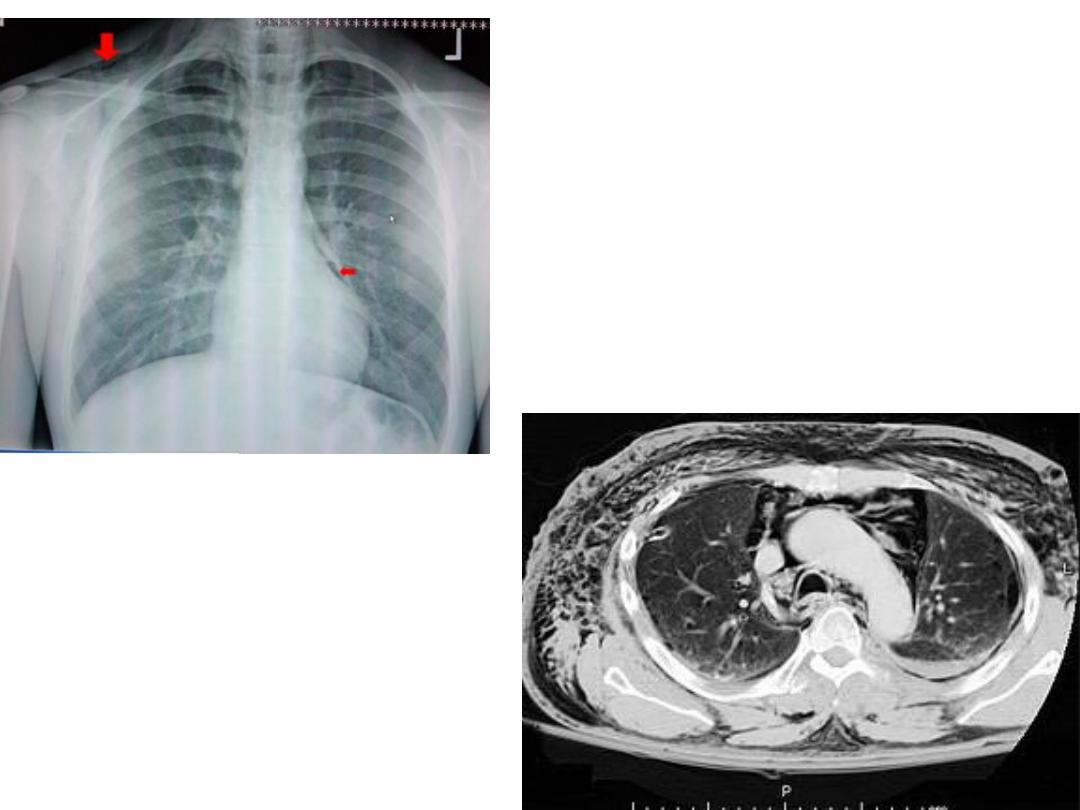

• Pneumomediastinum : Air in the mediastinum indicates a tear in the

oesophagus or an air leak from a bronchus (provided the air has not tracked

into the mediastinum from the root of the neck, adjacent chest wall or

retroperitoneum). These tears may be spontaneous or follow trauma, most

commonly from endoscopy, following forceful vomiting (Boerhaave’s

syndrome) or the ingestion of sharp foreign bodies Spontaneous leakage from

small bronchi in the lungs is most commonly seen in patients with asthma.

• The air, which tracks through the interstitial tissues of the lung into the

mediastinum, is seen as fine streaks of transradiancy within the mediastinum,

often extending upward into the neck.

Hodgkin lymphoma

Posterior mediastinal mass

Teratoma contain fat and bone density areas

Ascending aorta curvilinear calcification

Large hiatus hernia, seen with fluid

in stomach

Right Pericardial fat pad

Rt. Cardiophrenic pericardial cyst

Morgagni, retrosternal, diaphragmatic hernia

Bronchogenic cyst

Aortic aneurysm

Aortic dissection

Pneumomediastinum

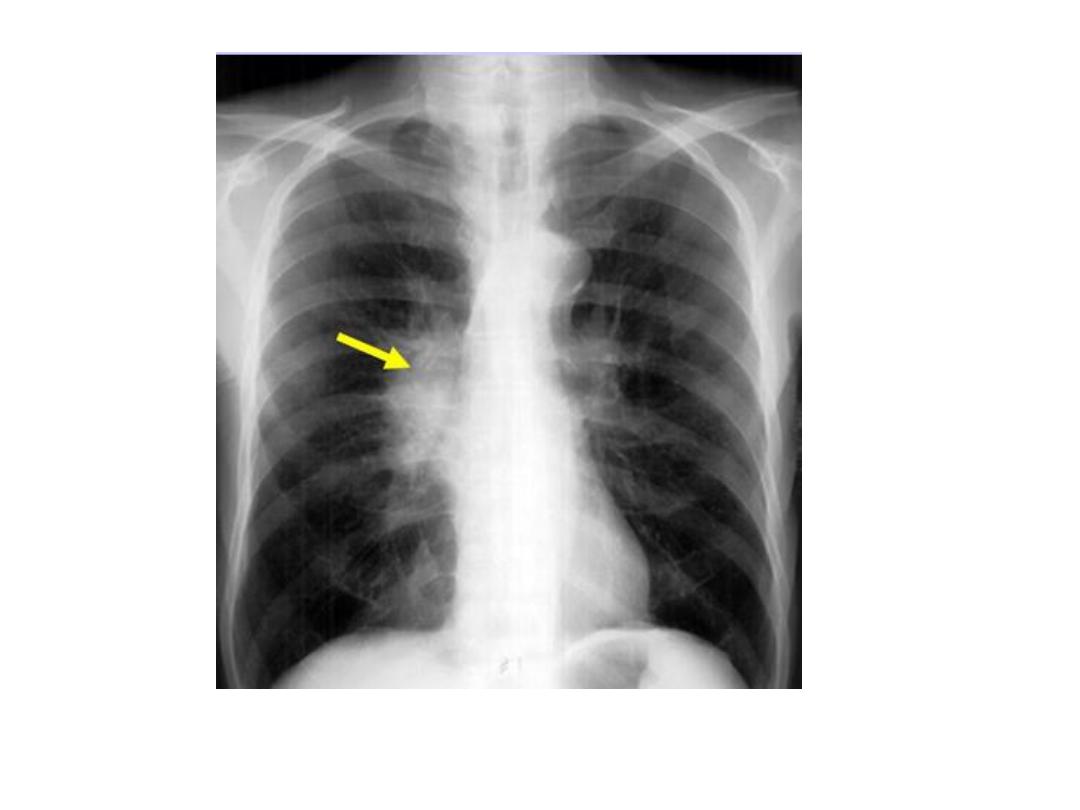

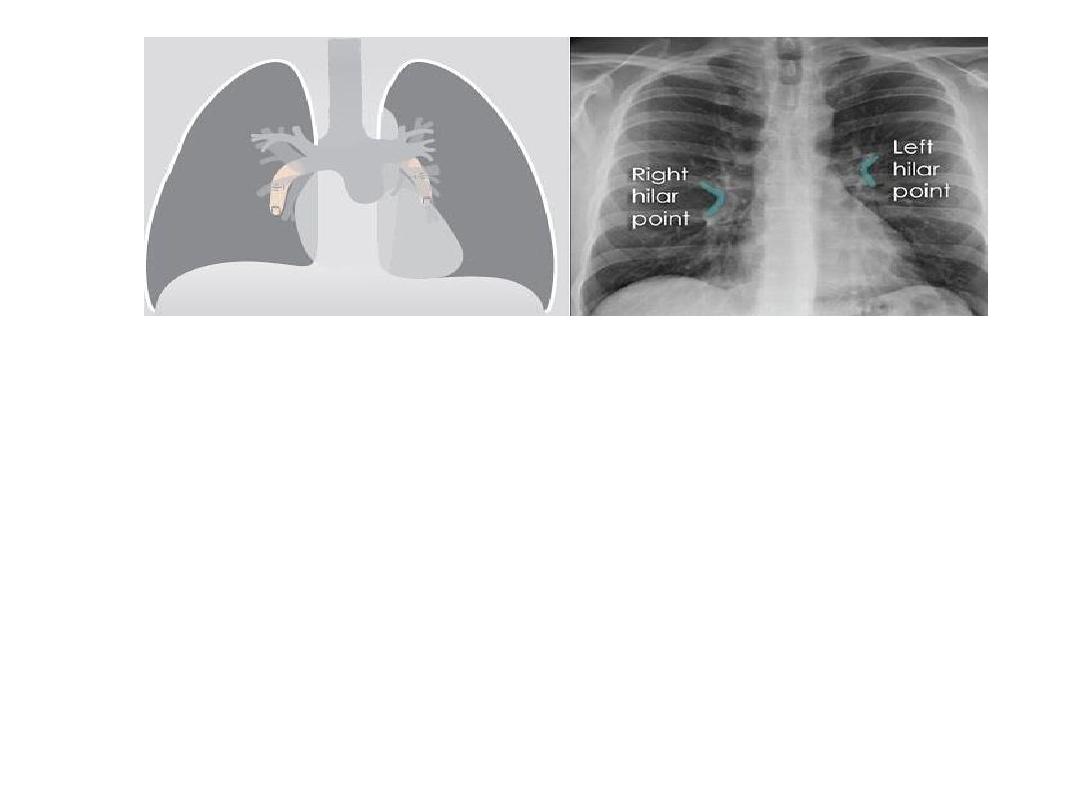

• Hilar enlargement : The normal hilar opacities are composed of pulmonary

arteries and veins.

• The main lower lobe arteries are typically 9–16 mm in diameter.

• Hilar lymph nodes cannot be identified as separate opacities on CXR and the walls

of the central bronchi are too thin to contribute to any extent to the bulk of the

hilar structures.

• Vascular enlargement often: demonstrates a branching pattern, is typically bilateral

and may be accompanied by cardiac enlargement.

• Hilar masses are nearly always due to either lymph node enlargement or carcinoma

of the bronchus. In practice, if there is any clinical doubt the patient will have CT for

further evaluation.

• Lymph node enlargement: Usually more than one hilar node is enlarged, so in

patients with lymphadenopathy the hilum appears lobulated in outline.

•

Unilateral enlargement of hilar lymph nodes may be due

to the following:

1- Metastases from carcinoma of the bronchus in which case the primary tumour is

often visible.

• metastases from other primary sites are rare.

2- Malignant lymphoma.

3- Infections, particularly tuberculosis, and histoplasmosis

• in endemic areas. Tuberculosis is the commonest cause of unilateral hilar

adenopathy in children.

•

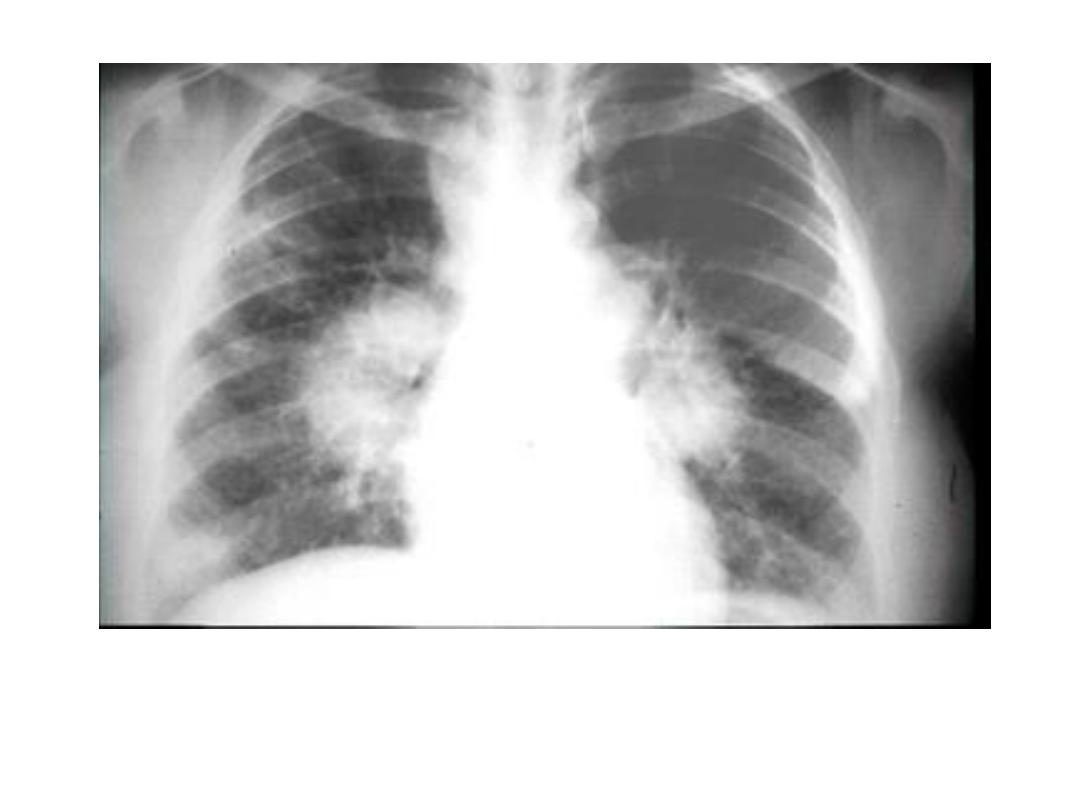

Bilateral enlargement of hilar nodes occurs in:

1- Sarcoidosis, which is far and away the commonest cause.

• The diagnosis is almost certain if the hilar enlargement is symmetrical and if the patient

is asymptomatic, or has either erythema nodosum or iridocyclitis. Simultaneous

enlargement of the right paratracheal nodes is common. Lung changes are sometimes

visible.

2- Malignant lymphoma.

3- Tuberculosis. African and Asian races show this form of the disease in which substantial

nodal enlargement can be a feature. It is rare to see bilateral hilar enlargement due to

tuberculosis in Caucasians.

4- Fungal diseases, which are rare causes of bilateral hilar enlargement.

• Neoplasm : Primary carcinoma of the bronchus frequently presents as a hilar mass.

• If lobar collapse/consolidation or narrowing of the adjacent bronchus is visible the

diagnosis of carcinoma is virtually certain.

• Diaphragm : Elevation of the diaphragm may be bilateral or unilateral.

• It is may be : 1- secondary to abdominal distension/pathology (such

• as an abdominal mass or a subphrenic abscess), 2- volume loss in the adjacent lung or 3-

a phrenic nerve palsy.

• It is also important to realize that minor elevation of a hemidiaphragm is a relatively

common incidental finding of no significance.

• Marked elevation of one hemidiaphragm with no other visible abnormality suggests

either paralysis or eventration.

• Paralysis results from disorders of the phrenic nerves, e.g. invasion by carcinoma of

the bronchus or damage following thoracic surgery.

• The signs are elevation of one hemidiaphragm, which on fluoroscopy or ultrasound

shows paradoxical movement, i.e. it moves upward on inspiration.

• Eventration of the diaphragm is a congenital condition in which the diaphragm

lacks muscle and becomes a thin membranous sheet.

• Except in the neonatal period it is almost always an incidental finding and does not

cause symptoms.

• Eventration may involve all (usually the left) or part of one hemidiaphragm,

resulting in a smooth ‘hump’ .

• Chest wall : Because ribs are curved structures, some portions are always

foreshortened on CXRs. Therefore, if a rib abnormality is suspected, oblique views

should be obtained for further clarification.

• Soft tissue swelling occurs with a number of rib lesions: fractures, infections and

neoplasms.

• The soft tissue swelling may be more obvious than the rib lesion, so vital to use

oblique views or CT as necessary.

• Congenital abnormalities of the ribs are common, but rarely of clinical significance.

It is important not to mistake bifid ribs or fused ribs for lung opacities on plain

films.

Unilateral rt. Hilar LNE, increase density,

lobulated outline.

Identify main lower lobe pulmonary arteries: They can be compared to a little finger

pointing downwards and medially. Sometimes, usually on the left side – it can appear

only as the proximal phalanx of the finger.

Interpretation: If the little finger shadow of the right lower lobe artery is not seen

then you must check for evidence suggesting collapse of the right lower lobe.

Identify the hilar point: Look for the site where the most superior upper lobe vessel –

either vein or artery – crosses the lateral margin of the little finger. The point of

crossing is known as hilar point and forms a horizontal “vee” (> or <).

Interpretation: The left hilum must never be lower than the right hilum. Whenever a

left hilum appears lower than the right hilum – look for other evidence suggestive of:

1- Collapse of either the left lower lobe or of the right upper lobe or 2- Enlargement

of the right hilum

Bilateral hilar LNE

TB bilateral hilar and rt. Para tracheal calc. LNs and

calc. complex in left upper lobe

Hodgkin lymphoma, ant. Med. LNs

Subphrenic abscess with elevation

of rt. hemidiaphragm

RUL collapse elevation rt. hemidiaphragm

Rib metastasis

Rib fractures

Bifid rib