Arrhythmia in pediatric age group

The normal heart rate varies with age. The younger the child, the faster the heart rate. Therefore, the

definitions of bradycardia (<60 beats/minute) and tachycardia (>100 beats/minute) used for adults do

not apply to infants and children. Tachycardia is defined as a heart rate beyond the upper limit of

normal for the patient's age, and bradycardia is defined as a heart rate slower than the lower limit of

normal

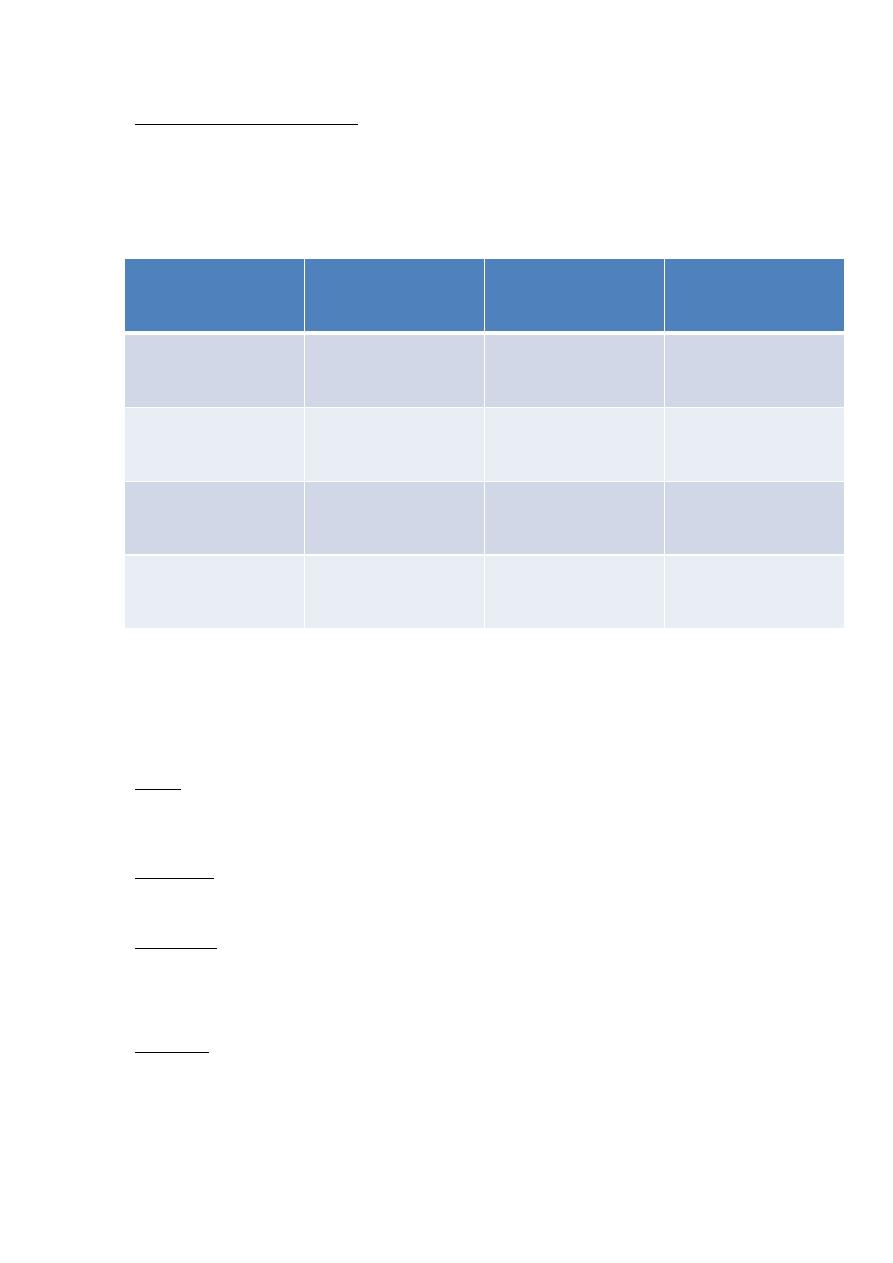

Age

Mean (range)

Age

Mean (range)

Newborn

145 (90–180)

4yr

108 (72–135)

6 mo

145 (106-185)

6yr

100 (65–135)

1 yr

132 (105-170)

10yr

90 (65–130)

2 yr

120 (90–150)

14yr

85 (60–120)

SINUS TACHYCARDIA

Characteristics of sinus rhythm are present . The rate is faster than the upper limit of normal for age .A

rate greater than 140 beats/minute in children and greater than 170 beats/minute in infants may be

significant. The heart rate is usually less than 200 beats/minute in sinus tachycardia

Causes

Anxiety, fever, hypovolemia or circulatory shock, anemia, congestive heart failure (CHF),

administration of catecholamines, thyrotoxicosis, and myocardial disease are possible causes.

Significance

Increased cardiac work is well tolerated by healthy myocardium.

Management

The underlying cause is treated

SINUS BRADYCARDIA

Description

The characteristics of sinus rhythm are present (see previous description), but the heart rate is slower

than the lower limit of normal for the age .A rate slower than 80 beats/minute in newborn infants and

slower than 60 beats/minute in older children may be significant

Causes

Sinus bradycardia may occur in normal individuals and trained athletes. It may occur with vagal

stimulation, increased intracranial pressure, hypothyroidism, hypothermia, hypoxia, hyperkalemia, and

administration of drugs such as digitalis and β-adrenergic blockers.

Significance

In some patients, marked bradycardia may not maintain normal cardiac output.

Management

The underlying cause is treated.

SUPRAVENTRICULAR TACHYCARDIA

The heart rate is extremely rapid and regular (usually 240 ± 40 beats/minute).

Causes

1-No heart disease is found in about half of patients. This idiopathic type of SVT occurs more

commonly in young infants than in older children.

2-WPW preexcitation is present in 10% to 20% of cases, which is evident only after conversion to

sinus rhythm.

3-Some congenital heart defects (e.g., Ebstein's anomaly, single ventricle, and congenitally

corrected transposition of the great arteries) are more susceptible to this arrhythmia.

4-SVT may occur following cardiac surgeries.

Significance

1-SVT may decrease cardiac output and result in CHF.

2-Many infants tolerate SVT well. If the tachycardia is sustained for 6 to 12 hours, signs of CHF

usually develop.

3-Clinical manifestations of CHF include irritability, tachypnea, poor feeding, and pallor. When

CHF develops, the infant's condition can deteriorate rapidly. Older children may complain of chest

pain, palpitation, and shortness of breath, lightheadedness, and fatigue.

Management

1-Vagal stimulatory maneuvers (unilateral carotid sinus massage, gagging, and pressure on an

eyeball) may be effective in older children but are rarely effective in infants. Placing an ice-water

bag on the face (for up to 10 seconds) is often effective in infants (by diving reflex).

2-Adenosine is considered the drug of choice. It has negative chronotropic, dromotropic, and

inotropic actions with a very short duration of action (half-life <10 seconds) and minimal

hemodynamic consequences. Adenosine is effective for almost all reciprocating SVT (in which the

AV node forms part of the reentry circuit) and for both narrow- and wide-complex regular

tachycardia. It is not effective for irregular tachycardia. It is not effective for non-reciprocating

atrial tachycardia, atrial flutter or fibrillation, and ventricular tachycardia, but it has differential

diagnostic ability. Its transient AV block may unmask atrial activities by slowing the ventricular

rate and thus help to clarify the mechanism of certain supraventricular arrhythmias

Adenosine is given by rapid IV bolus followed by a saline flush, starting at 50 μg/kg, increasing in

increments of 50 μg/kg every 1 to 2 minutes. The usual effective dose is 100 to 150 μg/kg with

maximum dose of 250 μg/kg.

3. If the infant is in severe CHF, emergency treatment is directed at immediate cardioversion. The

initial dose of 0.5 joule/kg is increased in steps up to 2 joule/kg.

4. Esmolol, other β-adrenergic blockers, verapamil, and digoxin have also been used with some

success. Intravenously administered propranolol has been commonly used to treat SVT in the

presence of WPW syndrome. IV verapamil should be avoided in infants younger than 12 months

because it may produce extreme bradycardia and hypotension in infants.

5. For postoperative atrial tachycardia (which requires rapid conversion), IV amiodarone may

provide excellent results. The side effects may include hypotension, bradycardia, and decreased

left ventricular (LV) function.

6. Overdrive suppression (by transesophageal pacing or by atrial pacing) may be effective in

children who have been digitalized.

7. Radiofrequency catheter ablation or surgical interruption of accessory pathways should be

considered if medical management fails or frequent recurrences occur. Radiofrequency ablation

can be carried out with a high degree of success, a low complication rate, and a low recurrence rate

After termination of SVT send child for

1- ECG to exclude prexcitation syndrome

2- Echo for structural heart disease as cardiomyopathy and Ebstien anomaly

3- Thyroid function test and serum electrolyte

Prevention of Recurrence of SVT

1-In infants without WPW preexcitation, oral propranolol for 12 months is effective. Verapamil

can also be used but it should be used with caution in patients with poor LV function and in young

infants.

2- In infants in CHF and ECG evidence of WPW preexcitation, one may start with digoxin (just to

treat CHF), but digoxin should be switched to propranolol when the infant's heart failure improves.

3- In infants or children with WPW preexcitation on the ECG, propranolol or atenolol is used in the

long-term management. In the presence of WPW preexcitation, digoxin or verapamil may increase the

rate of antegrade conduction of the impulse through the accessory pathway and should be avoided

ock

Heart bl

First-Degree Atrioventricular Block

Description.

The PR interval is prolonged beyond the upper limits of normal for the patient's age and heart rate

Causes.

First-degree AV block can appear in otherwise healthy children and young adults, particularly in

athletes. Other causes include congenital heart diseases (such as endocardial cushion defect, atrial

septal defect, Ebstein's anomaly), infectious disease, inflammatory conditions (rheumatic fever),

cardiac surgery, and certain drugs (such as digitalis, calcium channel blockers).

Significance.

First-degree AV block does not produce hemodynamic disturbance. It sometimes progresses to a more

advanced AV block.

Management.

No treatment is indicated, except when the block is caused by digitalis toxicity

Second-Degree Atrioventricular Block

MOBITZ TYPE I

Description.

The PR interval becomes progressively prolonged until one QRS complex is dropped completely

Causes.

Mobitz type I AV block appears in otherwise healthy children. Other causes include myocarditis,

cardiomyopathy, myocardial infarction, congenital heart defect, cardiac surgery, and digitalis toxicity.

Significance.

The block is at the level of the AV node. It usually does not progress to complete heart block.

Management.

The underlying causes are treated.

•

MOBITZ TYPE II

Description.

The AV conduction is “all or none.” AV conduction is either normal or completely blocked

Causes.

Causes are the same as for Mobitz type I.

Significance.

The block is at the level of the bundle of His. It is more serious than type I block because it may

progress to complete heart block

Management.

The underlying causes are treated. Prophylactic pacemaker therapy may be indicated

Third-Degree Atrioventricular Block

Description.

In third-degree AV block (complete heart block), atrial and ventricular activities are entirely

independent of each other

1

.

The P waves are regular (regular P-P interval), with a rate comparable to the normal heart rate

for the patient's age. The QRS complexes are also regular (regular R-R interval), with a rate

much slower than the P rate.

2

.

In congenital complete heart block, the duration of the QRS complex is normal because the

pacemaker for the ventricular complex is at a level higher than the bifurcation of the bundle of

His. The ventricular rate is faster (50 to 80 beats/minute) than that in the acquired type, and

the ventricular rate is somewhat variable in response to varying physiologic conditions.

3

.

In surgically induced or acquired (after myocardial infarction) complete heart block, the QRS

duration is prolonged because the pacemaker for the ventricular complex is at a level below

the bifurcation of the bundle of His. The ventricular rate is in the range of 40 to 50

beats/minute (idioventricular rhythm) and the ventricular rate is relatively fixed.

Causes

Congenital Type.

Causes are an isolated anomaly (without associated structural heart defect), structural heart disease

such as congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries, or maternal diseases such as systemic

lupus erythematosus, Sjögren's syndrome, or other connective tissue disease.

Acquired Type.

Cardiac surgery is the most common cause of acquired complete heart block in children. Other rare

causes include severe myocarditis. Lyme carditis, acute rheumatic fever, mumps, diphtheria,

cardiomyopathies, tumors in the conduction system, overdoses of certain drugs, and myocardial

infarction. These causes produce either temporary or permanent heart block.

Significance

1

.

Congestive heart failure (CHF) may develop in infancy, particularly when there are associated

congenital heart defects.

2

.

Patients with isolated congenital heart block who survive infancy are usually asymptomatic

and achieve normal growth and development for 5 to 10 years. Chest x-ray films may show

cardiomegaly.

3

.

Syncopal attacks (Stokes-Adams attacks) may occur with a heart rate below 40 to 45

beats/minute. A sudden onset of acquired heart block may result in death unless treatment

maintains the heart rate in the acceptable range.

Management

1

.

Atropine or isoproterenol is indicated in symptomatic children and adults until temporary

ventricular pacing is secured.

2

.

A temporary transvenous ventricular pacemaker is indicated in patients with heart block, or it

may be given prophylactically in patients who might develop heart block.

3

.

No treatment is required for children with asymptomatic congenital complete heart block with

acceptable rate, narrow QRS complex, and normal ventricular function.