Dr.Mushtaq Talib Hussein

F.I.B.M.S(ortho.) C.A.B.O(ortho.)

Elbow and Forearm

CLINICAL ASSESSMENT

S

YMPTOMS

Pain from the elbow is fairly diffuse and may extend into the forearm. Localized pain

over the lateral or medial epicondyle of the humerus is usually due to tendinitis.

Stiffness, if it is mild, may hardly be noticed. If it is severe, it can be very disabling;

the patient may be unable to reach up to the mouth (loss of flexion) or the perineum

(loss of extension);

Swelling may be due to injury or inflammation; a soft lump on the back of the elbow

suggests an olecranon bursitis.

Deformity is uncommon except in rheumatoid arthritis and after trauma. Always ask

about previous injuries.

Ulnar nerve symptoms (tingling, numbness and weakness of the hand) may occur in

elbow disorders because of the nerve’s proximity to the joint.

S

IGNS

Both upper limbs should be completely exposed, and it is essential to look at the back

of the elbow as well as the front. Often the neck, shoulders and hands also

need to be examined.

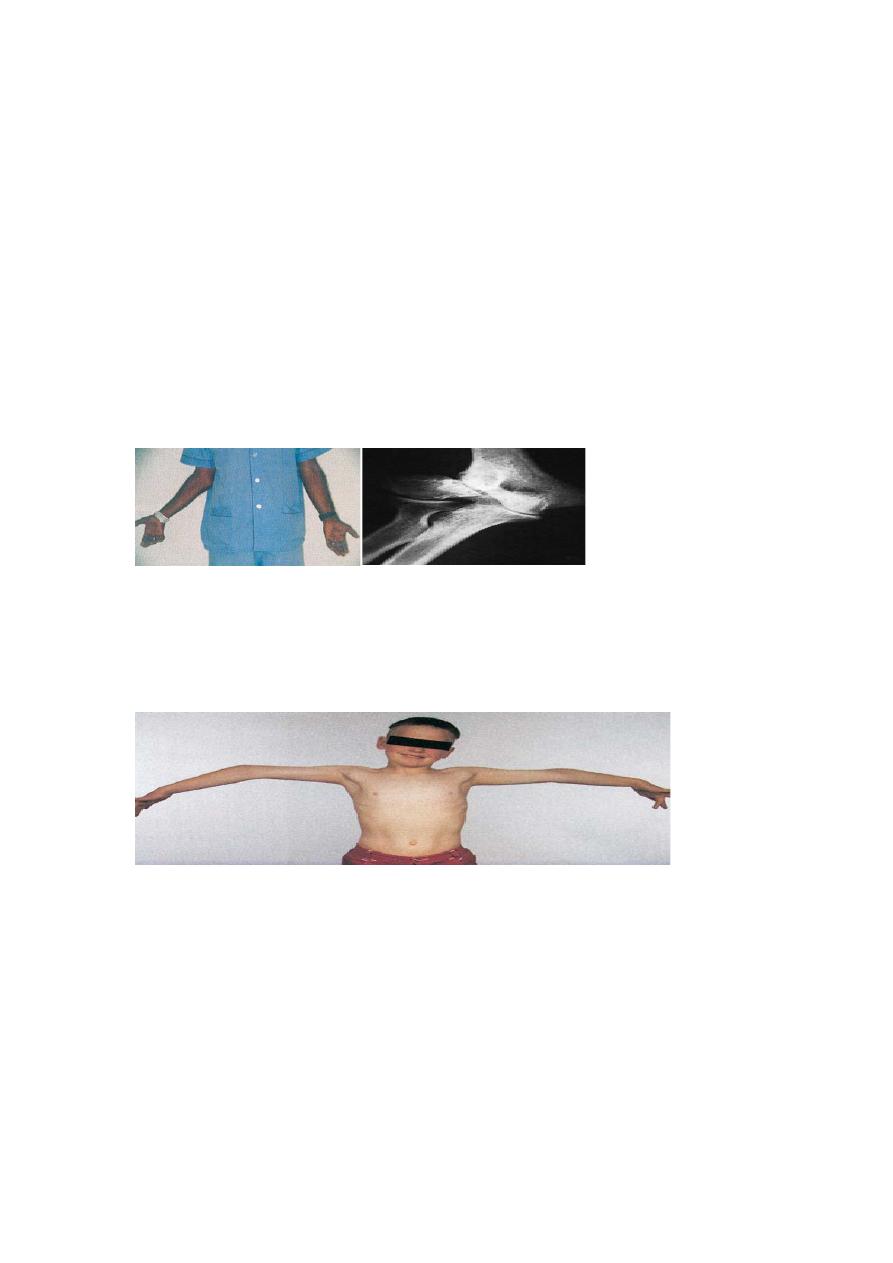

Varus and valgus deformities (cubitus varus and cubitus valgus) are usually the result

of trauma around the elbow. By far the best way to demonstrate a varus deformity is

to ask the patient to lift his or her arms sideways to shoulder height; in this position

the deformity becomes much more obvious, the arm taking on the appearance of a

rifle butt (gunstock deformity,

CONGENITAL DISORDERS

congenital dislocation of the radial head

This may be anterior or posterior and is usually bilateral.

The patient may notice the lump, which is easily palpable and can be felt to move

when the forearm is rotated. X-rays show that the dislocated radial head is dome-

shaped (due to abnormal modelling).

Congenital synostosis

Congenital deficiencies of the forearm bones are occasionally associated with fusion

of the humerus to the radius or ulna. This disabling condition is, fortunately, very rare.

A more useful angle of forearm rotation can

be achieved by osteotomy.

Proximal radio-ulnar synostosis causes loss of rotation, but elbow flexion is retained

Acquired deformities

Cubitus valgus

The normal carrying angle of the elbow is 5–15 degrees of valgus; anything more than

this is regarded as a valgus deformity, which is usually quite obvious when the patient

stands with arms to the sides and palms facing forwards.

The commonest cause is longstanding non-union of a fractured lateral condyle; the

deformity may be associated with marked prominence of the medial condylar outline.

The importance of cubitus valgus is the liability to delayed ulnar palsy;

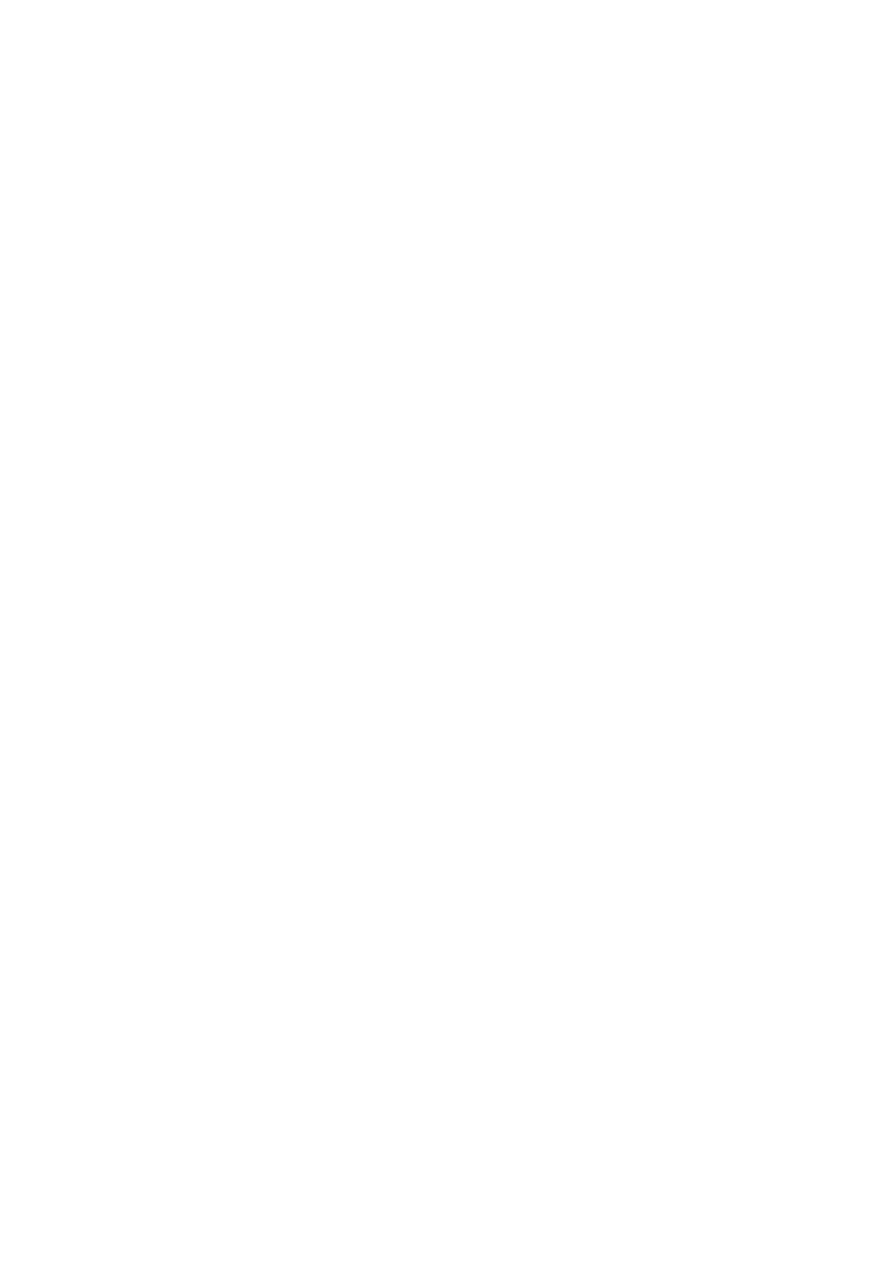

cubitus varus (‘gun-stock’ deformity)

The deformity is most obvious when the elbow is extended and the arms are elevated.

The most common cause is malunion of a supracondylar fracture.

The deformity can be corrected by a wedge osteotomy of the lower humerus but this

is best left until skeletal maturity.

‘pulled elbow’

Downward dislocation of the head of the radius from the annular ligament is a fairly

common injury in children under the age of 6 years. There may be a history of the

child being jerked by the arm and subsequently complaining of pain and inability to

use the arm. The limb is held more or less immobile with the elbow fully extended

and the forearm pronated; any attempt to supinate the forearm is resisted. The

diagnosis is essentially clinical, though x-rays are usually obtained in order to exclude

a fracture.

If the history and clinical picture are suggestive, an attempt should be made to reduce

the subluxation or dislocation. While the child’s attention is diverted, the elbow is

quickly supinated and then slightly flexed; the radial head is relocated with a snap.

Loose bodies

Loose bodies in the elbow may be due to: (1) acute trauma (an osteocartilaginous

fracture); (2) osteochondritis dissecans; (3) synovial chondromatosis (a cluster of

mainly cartilaginous ‘pebbles’); or (4) osteoarthritis (separation of osteophytes).

The patient may complain of sudden locking and unlocking of the joint. Symptoms of

osteoarthritis may coexist.

A loose body is rarely palpable. When degenerative changes have occurred, extremes

of movement are limited.

X-rays may reveal the loose body or bodies in the special case of osteochondritis

dissecans there is a rarefied cystic area in the capitulum and enlargement of the radial

head. A CT arthrogram will define the size and the number of loose bodies.

If loose bodies are troublesome, they should be removed by arthroscopic or open

means, depending on the size of the loose body and the experience of the surgeon.

Tuberculosis

Clinical features

The elbow is affected in about 10 per cent of patients with skeletal tuberculosis.

Although the disease begins as synovitis or osteomyelitis, patients are rarely seen

until arthritis supervenes.

The most striking physical sign is the marked wasting.

X-rays

The typical features are peri-articular osteoporosis and joint erosion. There may also

be subchondral cystic lesions.

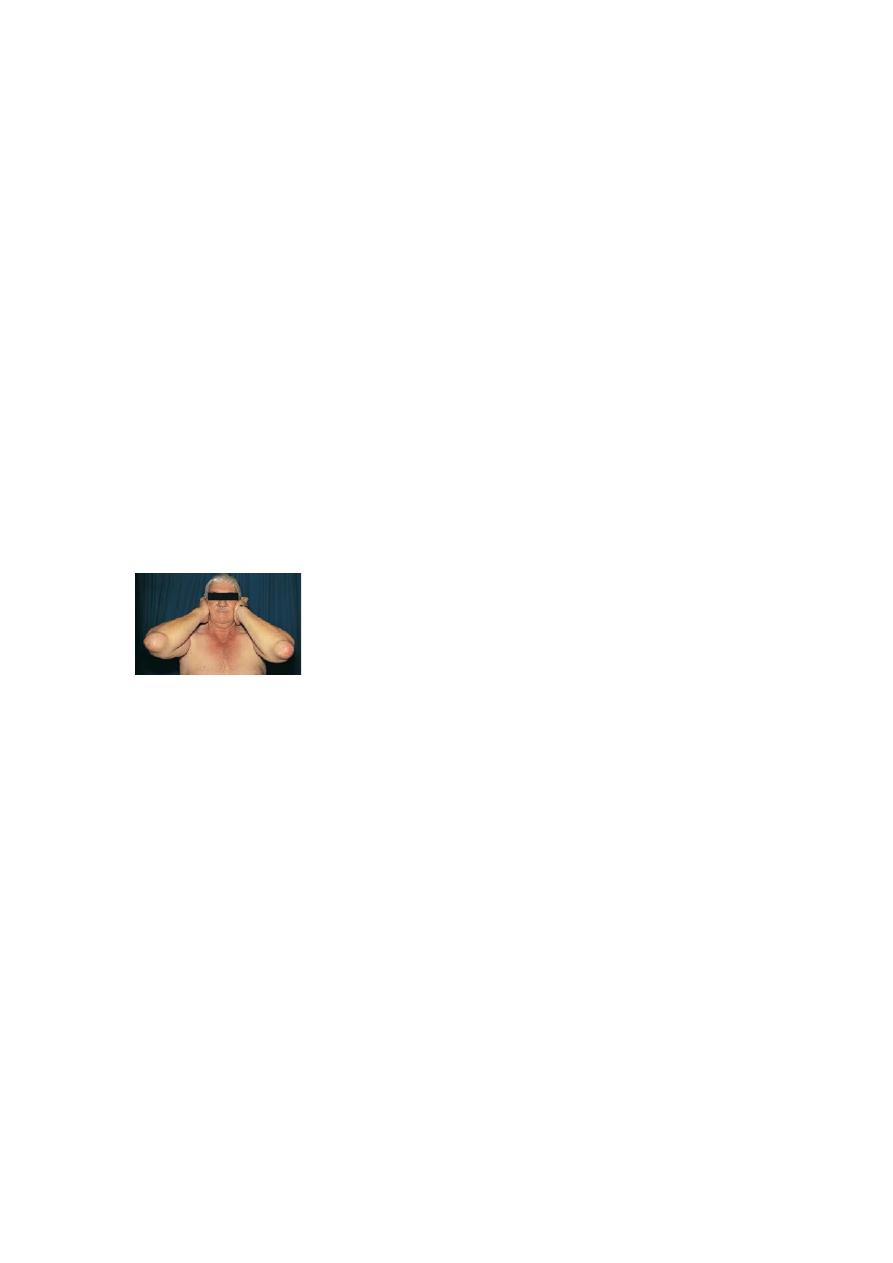

Rheumatoid arthritis

The elbow is involved in more than 50 per cent of patients with polyarticular

rheumatoid arthritis, and in the majority of cases the condition is bilateral.

Clinical features

Ulnar bursitis and rheumatoid nodules are often found on the back of the elbow even

if the joint itself is not affected. With true joint involvement, synovitis gives rise to

pain and tenderness, especially over the lateral aspect of the radio-humeral joint.

Later the entire elbow may be swollen. Movements are restricted but, if bone

destruction is marked, the joint becomes unstable.

Gout and pseudogout

The elbow – or more precisely the olecranon bursa –is a favourite site for gout. In an

acute attack the area rapidly becomes painful, swollen and inflamed. The swelling and

redness may extend well down the forearm and the condition is easily mistaken for

cellulitis or joint infection. The serum uric acid level may be raised and the bursal

aspirate will contain urate crystals.

Treatment is with high dosage anti-inflammatory preparations. Similar attacks occur

in pseudogout, due to the deposition of CPPD crystals, which can be identified in the

aspirate

Stiffness of the elbow

Stiffness of the elbow may be due to congenital abnormalities(various types of

synostosis, or arthrogryposis), infection, inflammatory arthritis, osteoarthritis or the

late effects of trauma.

Post-traumatic stiffness

For reasons that are not entirely clear, the elbow is particularly prone to post-

traumatic stiffness. The more obvious causes (as with other joints) are either extrinsic

(e.g. soft-tissue contracture or heterotopic bone formation), intrinsic (e.g. intra-

articular adhesions and articular incongruity), or a combination of these. Clinical

assessment should include examination of all the joints of the upper limb as well as an

evaluation of the functional needs of the particular patient.

The most effective treatment is prevention, by early active movement through a

functional range. if movement is restricted and fails to improve with exercise, serial

splintage may help; aggressive passive manipulation may aggravate more than help.

Epicondalgia

The elbow is prone to painful disorders of the tendon attachment. Sometimes this

occurs spontaneously, sometimes after sudden unaccustomed use.

Tennis elbow (lateral epicondalgia)

Pain and tenderness over the lateral epicondyle of the elbow (or, more accurately, the

bony insertion of the common extensor tendon) is a common complaint among tennis

players – but even more common in non-players who perform similar activities

involving forceful repetitive wrist extension. It is the extensor carpi radialis tendon

(which automatically extends the wrist when gripping) which is pathological in tennis

elbow.

Clinical features

The patient is usually an active individual of 30 or 40 years. Pain comes on gradually,

often after a period of unaccustomed activity involving forceful gripping and wrist

extension. It is usually localized to the lateral epicondyle, but in severe cases it may

radiate widely. It is aggravated by movements such as pouring out tea, turning a stiff

doorhandle, shaking hands or lifting with the forearm pronated. Among tennis players

it is usually blamed on faulty technique.

The elbow looks normal, and flexion and extension are full and painless.

Characteristically there is localized tenderness at or just below the lateral

epicondyle; pain can be reproduced by passively stretching the wrist extensors (by the

examiner acutely flexing the patient’s wrist with the forearm pronated) or actively by

having the patient extend the wrist with the elbow straight.

X-ray is usually normal, but occasionally shows calcification at the tendon origin.

Treatment

The first step is to identify, and then restrict, those activities which cause pain.

Modification of sporting style may solve the problem. A tennis elbow clasp is helpful.

The role of physiotherapy and manipulation is uncertain. Injection of the tender area

with corticosteroid and local anaesthetic relieves pain but is not curative.

Operative treatment

Some cases are sufficiently persistent or recurrent for operation to be indicated. The

origin of the common extensor muscle is detached from the lateral epicondyle.

Golfer’s elbow (medial Epicondylitis)

This is similar to tennis elbow but about three times less common. In this case it is the

pronator origin that is affected. Often there is an associated ulnar nerve neuropathy.

A medial collateral ligament injury should be excluded.

Treatment is the same as for lateral epicondylitis but the outcome of surgery seems

less predictable.

Baseball pitcher’s elbow

Repetitive, vigorous throwing activities can cause damage to the bones or soft-tissue

attachments around the elbow. Professional baseball players may develop hypertrophy

of the lower humerus and incongruity of the joint, or loose-body formation and

osteoarthritis.

Bursitis

The olecranon bursa sometimes becomes enlarged as a result of continual pressure or

friction; this used to be called ‘student’s elbow’. If the enlargement is a nuisance the

fluid may be aspirated.

The commonest non-traumatic cause is gout; there may be a sizeable lump with

calcification on x-ray. In rheumatoid arthritis, also, the bursa may become enlarged,

and sometimes nodules can be felt in the lump or just distal to it over the proximal

ulna. In both conditions other joints are likely to be affected as well.