• Diseases of the airways :

asthma :

The chest film in asthma:

1- usually normal 2- or shows only air-trapping with flattening of the diaphragm. 3-

Bronchial wall thickening may be seen.

• The main purpose of the CXR in asthma is:

1- to determine complications, e.g. atelectasis

2- to detect associated pneumonia

3- to exclude other causes of acute dyspnoea, e.g. pulmonary oedema, pneumothorax

or, rarely, tracheal obstruction.

• A CXR should only be undertaken when one or more of the above conditions are a

realistic possibility.

•

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis results from hypersensitivity

to

Aspergillus

fumigatus. Asthma is the cardinal

clinical feature of this disease. The radiological

signs are : 1- allergic consolidations in the lung, 2- proximal bronchiectasis,

particularly in the mid and upper zones. 3- The thickened walls of the dilated

bronchi may be visible on a CXR.

•

Bronchiolitis :

on CXR: 1- Severe bronchiolitis in young children, even when life

threatening, may show surprisingly little change on a CXR. 2- The major sign is

overinflation of the lungs, leading to a low position of the diaphragm. 3- Some

children show widespread, small, ill-defined areas of consolidation, but in many

the lungs are clear.

•

Acute bronchitis

Acute bronchitis in adults and older children does not produce

any radiological abnormality unless complicated by pneumonia.

•

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is

an imprecise, but convenient, term that includes several common diseases,

including chronic bronchitis and emphysema, and bronchiectasis.

•

Chronic bronchitis and emphysema

Chronic bronchitis is a clinical diagnosis based on productive

cough for at

least three consecutive months in two successive years. Pathologically, there is hypertrophy of the mucous

glands throughout the bronchial tree.

•

On CXR: 1- The CXR in uncomplicated chronic bronchitis is normal.

2- If the film is abnormal, a complication such as emphysema, pneumonia or cor pulmonale has occurred, and the

radiological features are then those of the complication in question.

•

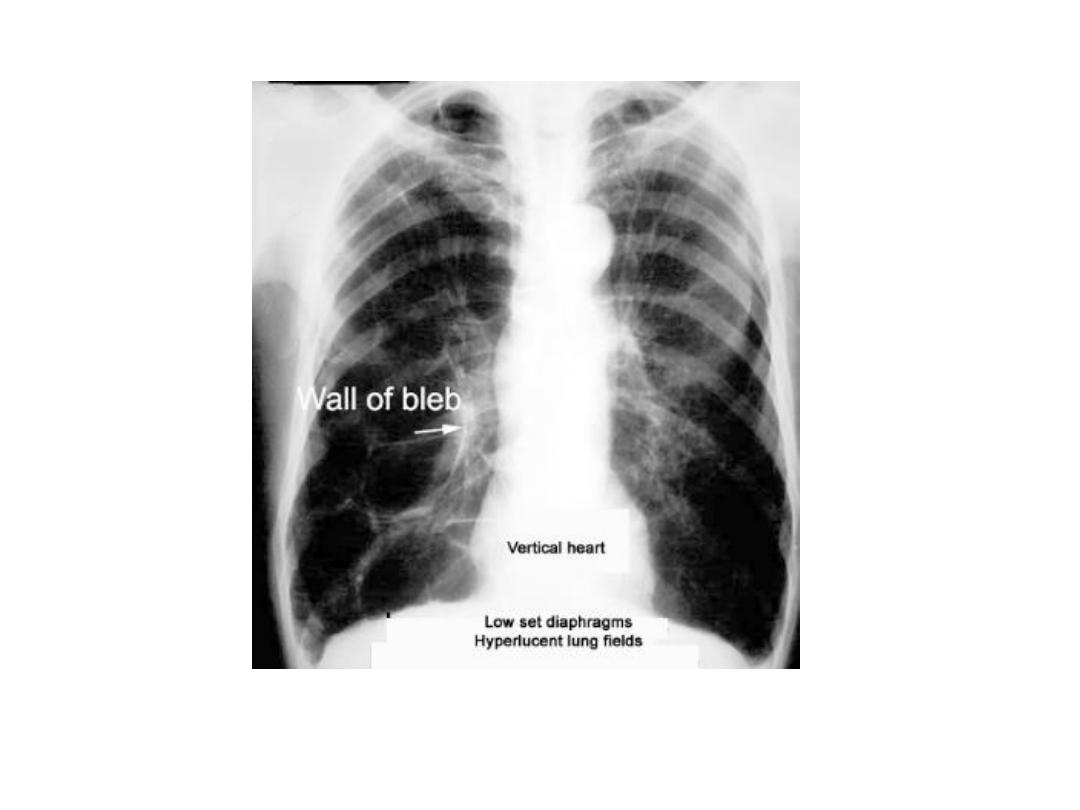

Emphysema is defined pathologically as an increase

beyond normal size of air-spaces distal to the terminal

bronchiole with destructive changes in their walls. The radiological signs of emphysema are:

1- Increased lung volume. The lungs increase in volume because of the combined effect of airways obstruction on

abnormally compliant lungs. : a- The diaphragm is pushed down and becomes low and flat b- The heart is

elongated and narrowed. C- The ribs are widely spaced and d- more lung lies in front of the heart and

mediastinum. Overinflation of the lungs can be said to be present if the hemidiaphragms at their midpoint are

below the seventh rib anteriorly or the 12th rib posteriorly.

2- Attenuation of the vessels : The reduction in size and number of the pulmonary blood vessels can be generalized

or localized. If severe, the involved area is called a bulla. The edge of a bulla is usually sharply demarcated. In

some cases, the normal lung adjacent to the bulla is compressed and appears opaque.

•

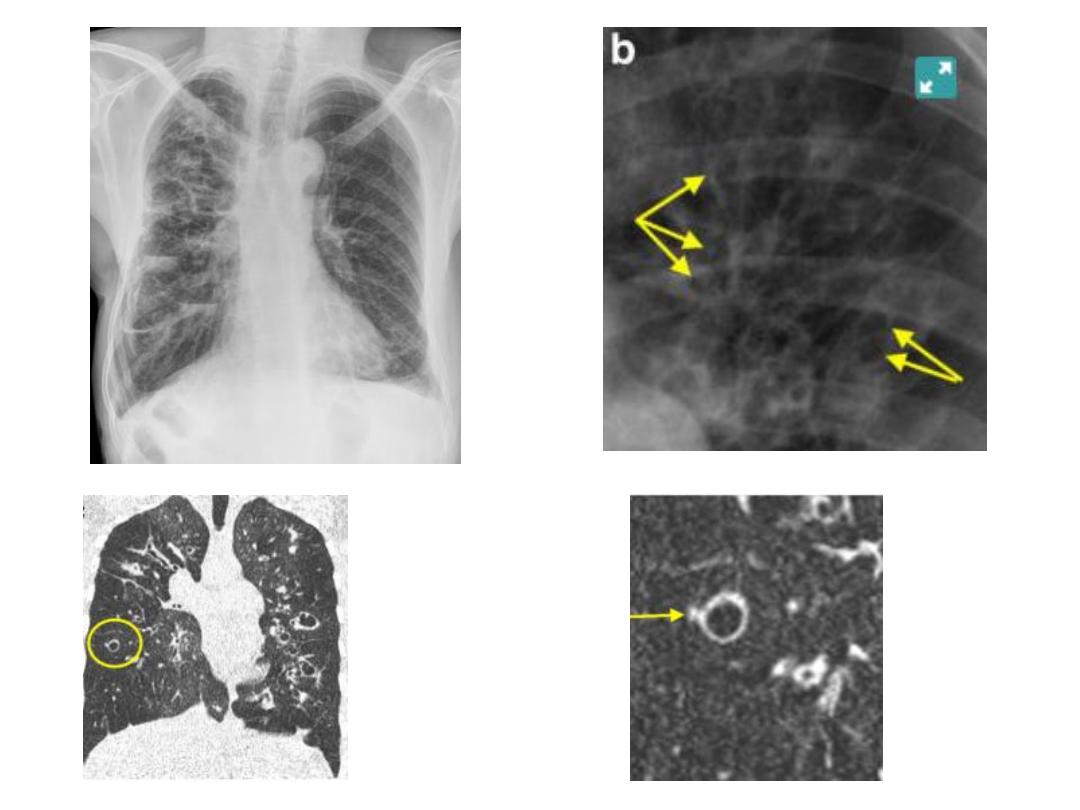

Bronchiectasis

is defined as irreversible dilatation of the bronchi, often accompanied by impairment of drainage

of bronchial secretions leading to persistent infection.

•

Conditions that cause bronchiectasis include pulmonary infection in childhood, cystic fibrosis and longstanding

bronchial obstruction.

•

The radiological features are:

1- Visibly dilated bronchi. If they contain air, the thickened walls of the dilated bronchi may be seen as tubular or ring

opacities. If filled with fluid, the dilated bronchi are either opaque or contain air–fluid levels. As these fluid levels

are very short, they have to be looked for very carefully.

2- Loss of volume of the affected lobe or lobes is almost invariable.

3- A proportion of patients with symptomatic bronchiectasis have a normal CXR.

•

High resolution CT is very useful both to diagnose bronchiectasis and to assess its extent.

•

Cystic fibrosis it is an inherited disorder of exocrine glands resulting in secretion of viscid mucus.

•

In cystic fibrosis, the small airways become blocked and secondary infections

•

supervene. The finding of a high sodium chloride concentration

•

in the sweat is diagnostic of the condition.

•

The radiological findings are:

1- Small, ill-defined consolidations, maximal in the upper zones, some of which show cavitation.

2- Bronchial wall thickening and the signs of bronchiectasis, both usually maximal in the upper zones.

3- Evidence of airway obstruction. The diaphragm is low and flat and the heart is narrow and vertical, until cor

pulmonale develops when cardiac enlargement may occur.

•

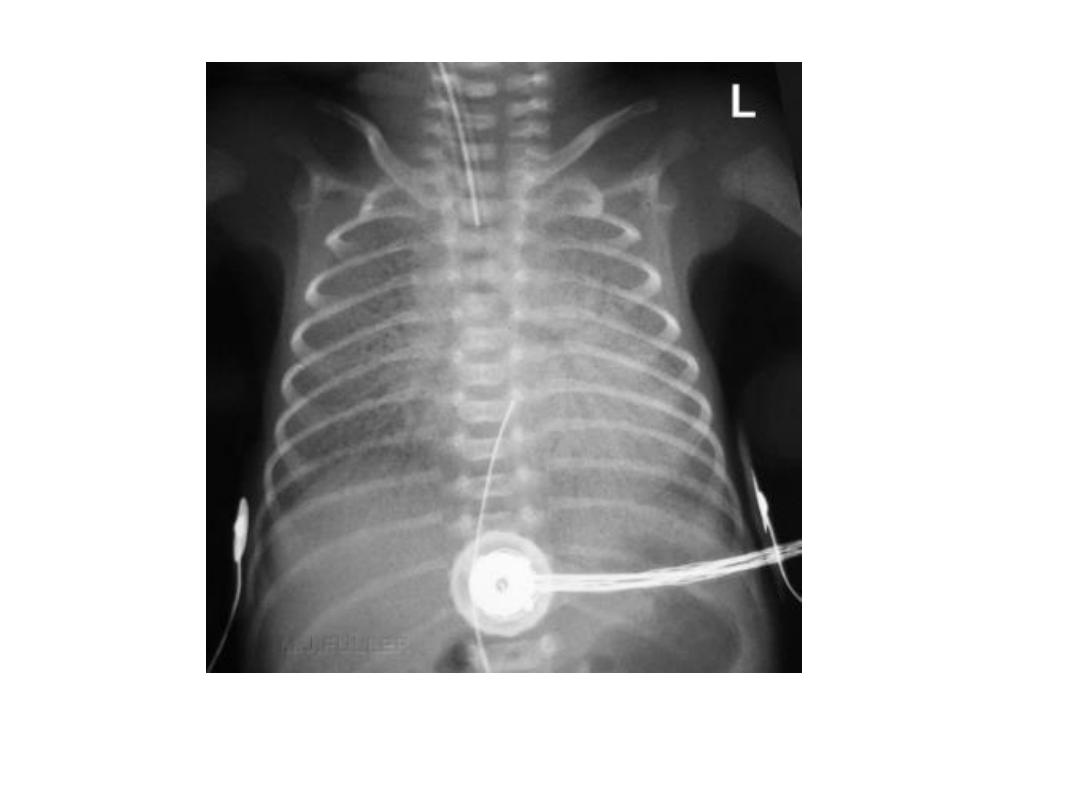

Respiratory distress in the newborn There are many causes of respiratory distress in the first few days of life.

•

Abnormalities are visible on the CXR in the majority.

•

Hyaline membrane disease is one of the commonest abnormalities.

•

It is a disease of the premature infant and is due to deficiency of surfactant in the lungs, Consequently, the alveoli

collapse, so preventing gas exchange.

•

The CXR appearance is one of the most important criteria in making the diagnosis.

•

The basic signs are: widespread, very small pulmonary opacities and visible air bronchograms , Air bronchograms

are visible because the bronchi are surrounded by airless alveoli. In the (milder )forms, the nodules are small and

the air bronchograms may be the most obvious and easily recognized sign. In the more (severe forms), the

pulmonary opacities become more obvious and may be confluent; the lungs then appear almost opaque, except

for air bronchograms. The changes are nearly always uniform in distribution.

•

Meconium aspiration on CXR: 1-

the pulmonary opacification is usually patchy and distinctly streaky.

2- Air bronchograms are not an obvious feature.

3- The diaphragm is often lower than normal due to airways obstruction associated with sticky meconium in the

bronchi.

•

. Complications of therapy In addition to establishing the

initial diagnosis in neonates with various causes of

respiratory distress, the CXR is vital in detecting complications of therapy. These include pneumothorax, lobar

collapse and pneumomediastinum.

•

Adult respiratory distress syndrome : is the name given to a syndrome in which the

pulmonary capillaries leak proteinaceous fluid into the surrounding pulmonary interstitium

and alveoli. The condition is also known as ‘non- cardiogenic pulmonary oedema’.

•

There are many precipitating causes including severe trauma, significant hypotension,

septicaemia and fat embolism.

•

Chest radiographs : show widespread pulmonary opacification resembling cardiogenic

pulmonary oedema at first, but the pulmonary opacification becomes more widespread and

more uniform over the ensuing 24–48 hours. The radiological abnormality may only develop

12–24 hours after the onset of tachypnoea, dyspnoea or hypoxaemia.

•

As patients with ARDS require assisted ventilation, the chest film is used to detect the

complications of ventilator therapy, notably pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum.

•

Pulmonary emboli and infarction Pulmonary emboli from thrombi originating in the veins of

the legs and pelvis are very common in patients confined to bed, particularly those with

heart disease and those who have had major surgery. Small emboli occurring over a long

period of time may cause pulmonary hypertension.

•

Radionuclide lung scans can be performed to confirm or exclude the diagnosis of pulmonary

emboli, but CT pulmonary angiography has become the investigation of choice.

•

Plain film abnormalities : 1- In most cases, even with massive pulmonary embolism, CXRs

show no abnormalities due to the emboli. 2- However, in some patients, particularly those

with heart disease, infarction occurs. Radiologically, infarcts cause one or more areas of

consolidation based on the pleura and the diaphragm. They often affect both lungs and are

indistinguishable from pneumonia. The differentiation between

pneumonia and pulmonary

infarction depends on clinical rather than radiological factors.

•

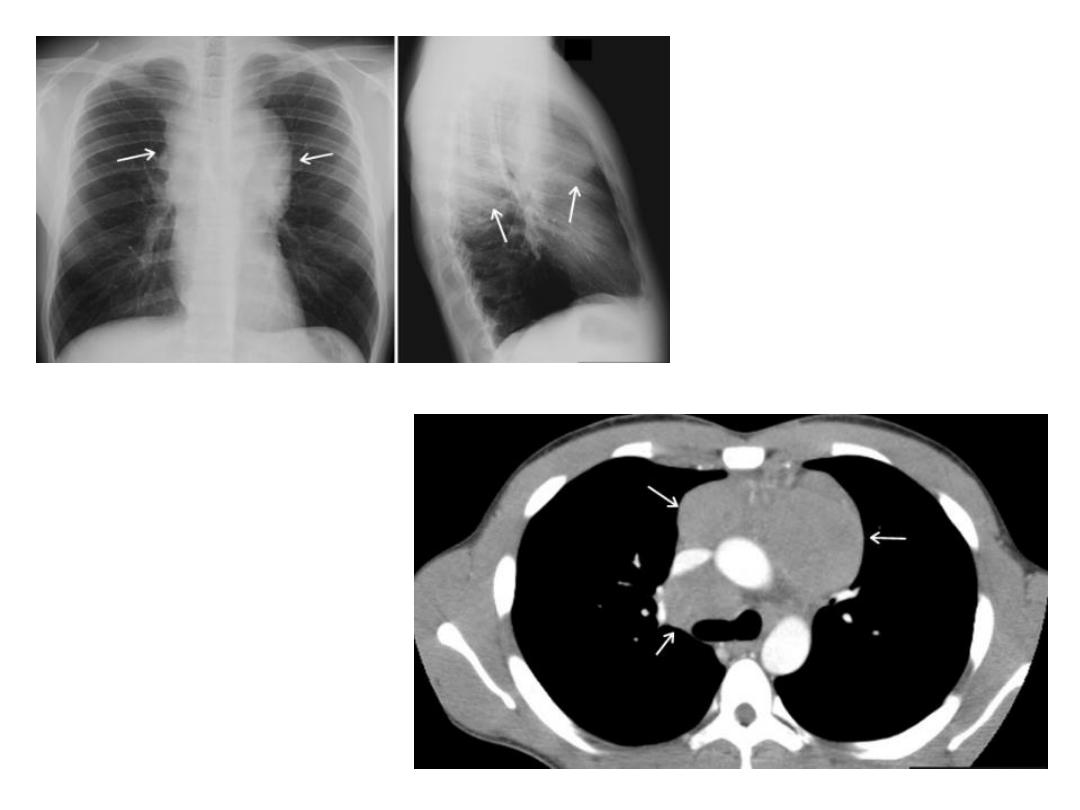

Computed tomography pulmonary angiography involves imaging the pulmonary arteries during a rapid

injection of intravenous contrast agent .

•

It shows the emboli as filling defects within the lumen of the opacified pulmonary arteries.

•

The technique can demonstrate emboli in large and medium-sized pulmonary vessels, but is less reliable

for excluding pulmonary emboli in the more distal, smaller pulmonary arteries.

•

Trauma to the chest In major trauma CT is often needed, but a CXR is usually sufficient following

minor trauma.

•

A rib fracture can b diagnosed by noting a break or step in the cortex of a rib. Special views of the

ribs may be necessary, as rib fractures are often invisible in the standard projections, particularly if

the fracture lies below the diaphragm. Extrapleural soft tissue swelling from bruising, or frank

haematoma, may be visible and guide the observer toward the site of the fracture.

•

Rib fractures are frequently multiple and may result in a flail segment.

•

Pleural effusion often accompanies rib fractures, the fluid frequently being blood. The following

features should be looked for.

•

Pneumothorax may occur if the lung is punctured by

direct injury or by the sharp edge of a rib fracture.

An air–fluid level in the pleural cavity due to the associated haemorrhage is common in such

situations.

•

Surgical emphysema of the chest wall may indicate the

escape of air from the lungs. The presence of

mediastinal emphysema in the absence of chest wall emphysema may indicate rupture of a

bronchus, which is a rare event.

•

Pulmonary contusion. Localized traumatic alveolar haemorrhage

and oedema may be seen whether or

not a rib fracture can be identified. The resulting pulmonary opacity is indistinguishable from other

forms of pulmonary consolidation, the relationship to the injury being important in establishing the

diagnosis.

•

Adult respiratory distress syndrome may follow severe

trauma to any part of the body. Fat embolism is

a specific subtype of ARDS, but its radiographic manifestations are identical to those of the other

causes of ARDS.

•

Rupture of the diaphragm is due to penetrating injury or

compression of the abdomen and may permit

herniation of the stomach or intestine into the chest. Such herniation is much commoner on the left

than the right. Gas lucencies of the stomach or intestine are seen above the presumed position of

the diaphragm, the diaphragm itself often being invisible due to an associated pleural effusion.

•

CT may be indicated to establish the diagnosis .

•

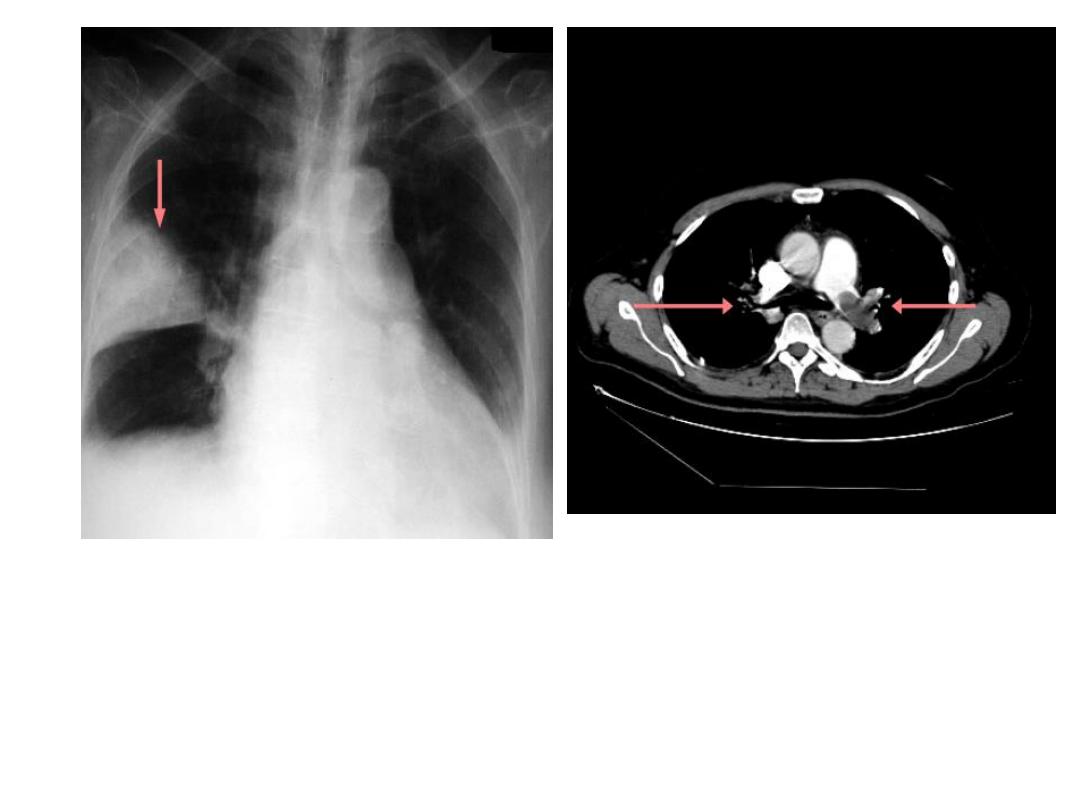

Rupture of the aorta is a particularly serious consequence

of rapid deceleration injuries. In patients

that survive, the injury to the aorta is usually at the level of the ligamentum arteriosum. Ruptured

aorta is a surgical emergency and is best diagnosed by CT angiography.

•

Mediastinal widening due to bleeding, with or without pleural

fluid, is the plain film sign of a

ruptured aorta, but mediastinal widening is a difficult sign to assess. It may be due to excess

mediastinal fat, or it may be artefactual due to the portable anteroposterior (AP) films that

are often the only films that can be taken in these severely injured patients.

•

CT may be used to confirm or exclude blood in the mediastinum.

•

When blood is identified, it may be due to bleeding from the aortic rupture or to bleeding

from other vessels, either arterial or venous. Although fractures of the ribs or sternum are

usually present, there are many cases of aortic rupture on record without visible damage to

the thoracic cage.

•

In some patients the diagnosis of aortic rupture is only made several months or years after

the injury, when the development of an aneurysm is noted.

•

Rupture of the tracheobronchial tree only occurs with major

chest trauma. The cardinal signs

are pneumomediastinum or pneumothorax that does not respond to a chest drain even on

suction. The main complication is subsequent bronchostenosis.

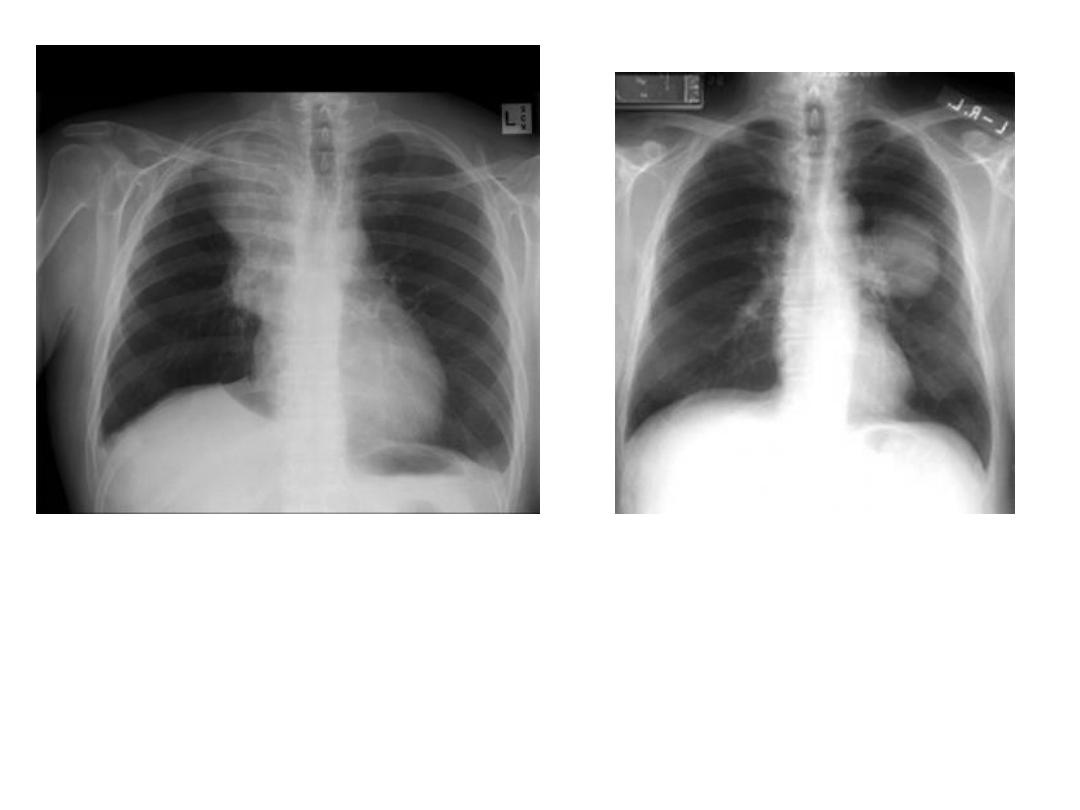

• Carcinoma of the bronchus

is one of the most common primary malignant tumours. It

has a clear association with cigarette smoking. It is convenient to consider the radiological

features of central and peripheral tumours separately.

•

Signs of a central tumour : 1- The tumour itself may present as a hilar mass with or without

narrowing of the adjacent major bronchus.

2- Collapse and/or consolidation of lung beyond the tumour . Lung collapse occurs because air is

absorbed beyond the obstructed bronchus and cannot be replaced, whereas consolidation is

the consequence of retained secretions and secondary infection.

•

Signs of a peripheral tumour: usually presents as a solitary pulmonary nodule/mass on plain

films or chest CT.

•

It is very unusual to see a lung carcinoma of less than 1 cm in diameter on a CXR. Much smaller

cancers, some even as small as a few millimetres may be discovered on CT .

•

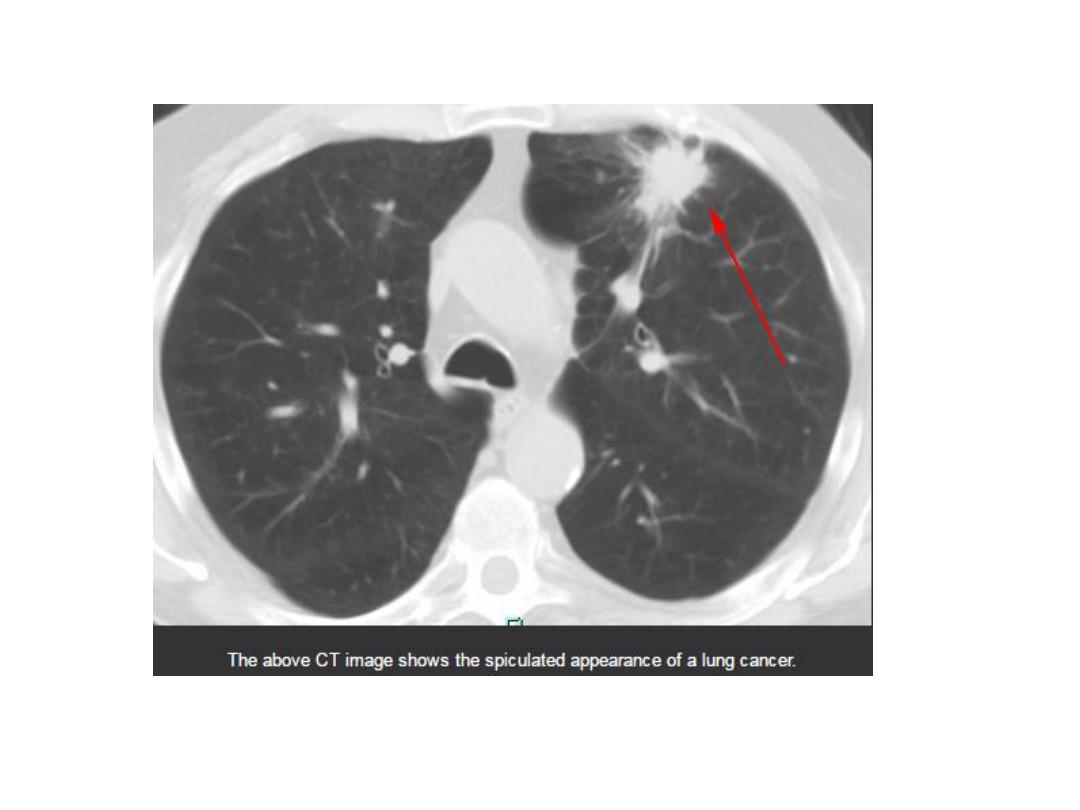

The signs of a peripheral primary carcinoma are:

1- A rounded opacity with an irregular border. Lobulation, notching and infiltrating edges are the

common patterns.

2- Cavitation within the mass. The walls of the cavity are classically thick and irregular, but thin-walled,

smooth cavities due to carcinoma do occur.

•

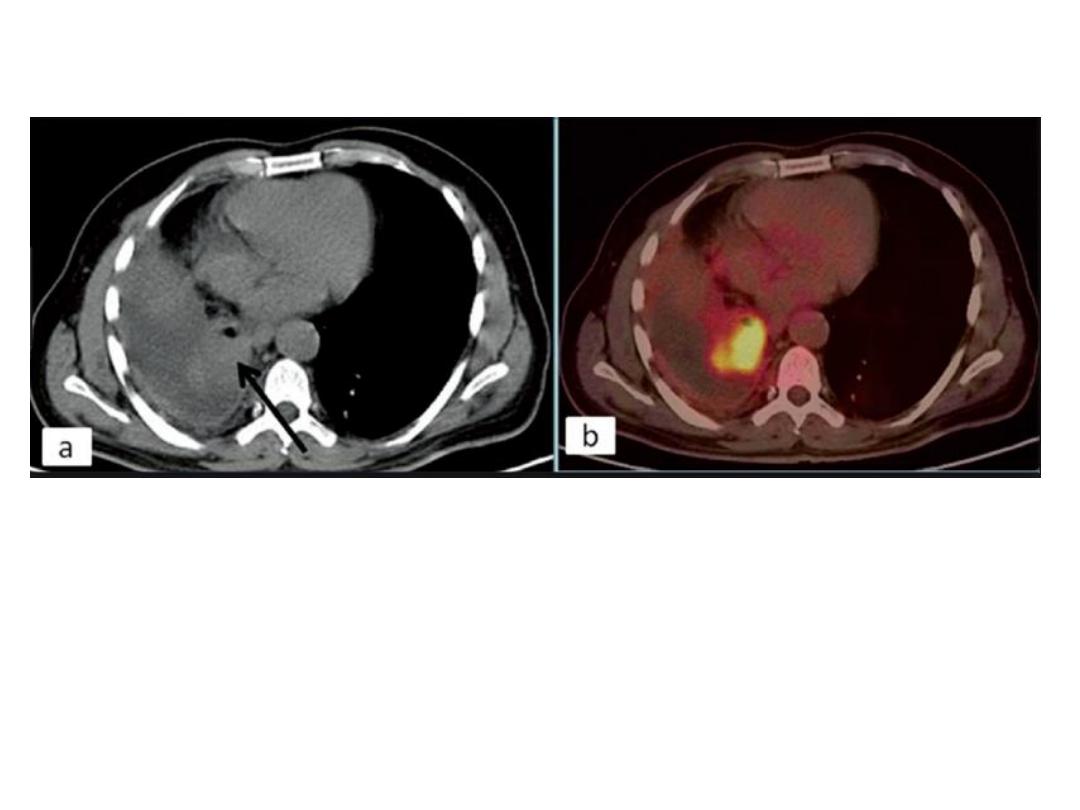

Spread of bronchial carcinoma: Evidence of the spread of bronchial carcinoma may be visible on

plain chest radiography, but CT has made a major contribution to the staging of lung cancer.

•

FDG-PET/CT scanning is now used routinely to stage potentially operable tumours.

•

MRI is only used for highly specific indications. The following features should be looked for:

•

Hilar and mediastinal lymph node enlargement due to lymphatic

spread of tumour. Only greatly

enlarged lymph nodes can be recognized on plain CXRs. CT, on the other hand, has the ability to

show even mildly enlarged nodes, which are not identifiable on plain film. Enlargement of lymph

nodes does not necessarily mean metastatic involvement because reactive hyperplasia to the

tumour or associated infection can be responsible for nodal enlargement, as can pre-existing

disease – notably previous granulomatous infection. FDG-PET/CT is used to identify neoplastic

nodes although false-positive scans are obtained in patients with incidental and often unimportant

inflammatory changes in the lymph nodes and false negatives can be seen in nodes below 1 cm in

diameter. If there is any doubt on imaging, prior to resection of the primary tumour, biopsies can be

obtained via mediastinoscopy or endobronchial ultrasound. It should be borne in mind, however,

that nodes of 2 cm or greater in short axis diameter which are PET positive in a patient with a

bronchial carcinoma, almost invariably contain metastatic neoplasm.

•

Pleural effusion in a patient with lung cancer is usually

due to malignant involvement of the pleura, but it may be

secondary to associated infection of the lung or coincidental, as in heart failure.

•

Invasion of the mediastinum is best assessed by CT because

the neoplasm is directly visualized and the detailed

anatomy is displayed .

•

Invasion of the chest wall. Destruction of a rib immediately

adjacent to a pulmonary opacity is

virtually diagnostic of bronchial carcinoma with chest wall invasion .

•

Recognizing the rib destruction can be difficult. It is important, therefore, to make a

conscious effort to look directly at the ribs adjacent to the tumour. CT (and MRI) can

demonstrate rib and soft tissue invasion when the bone is not visibly eroded on plain films.

•

Imaging techniques, even CT and MRI, may not always be reliable for determining chest wall

invasion, and local chest wall pain remains an important indication that the tumour has

crossed the pleura.

•

Rib metastases. Carcinoma of the lung frequently metastasizes

to the ribs, where it produces

bone destruction. Sclerotic secondary deposits from lung carcinoma are rare.

•

Pulmonary metastases. Primary lung carcinoma may

metastasize to other parts of the lungs.

The rounded opacities that result are similar to secondary deposits from other primary

tumours.

•

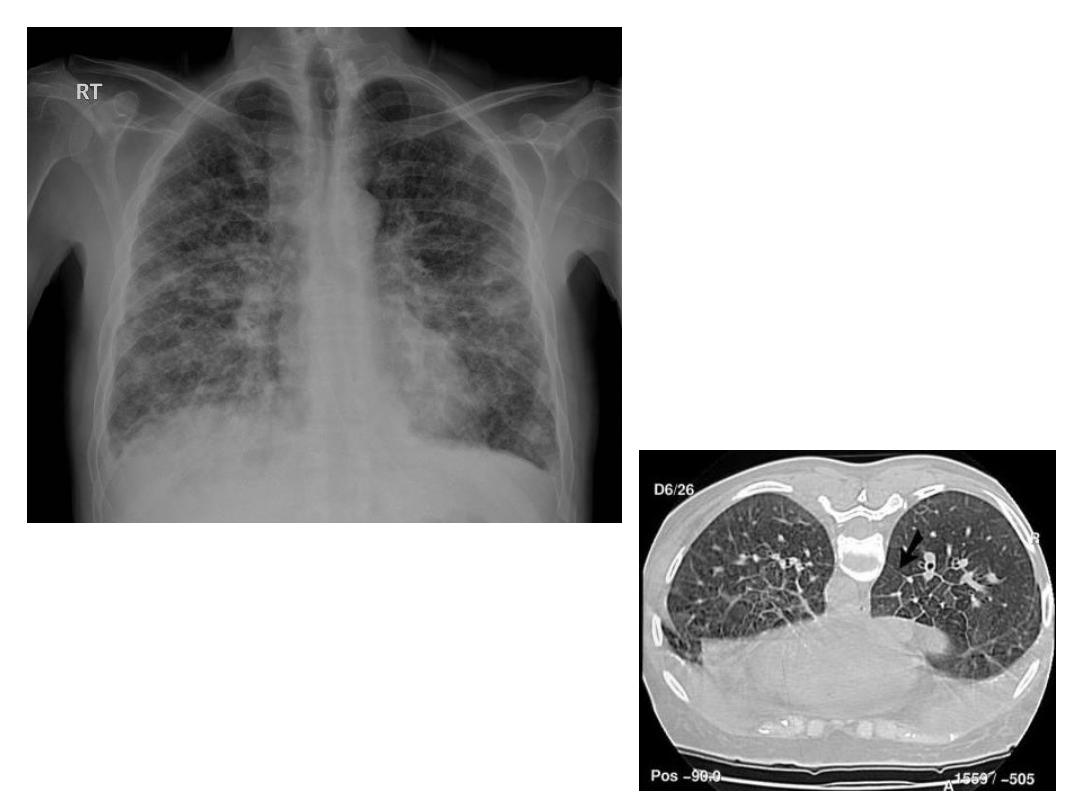

Lymphangitis carcinomatosa is the term applied to blockage

of the pulmonary lymphatics by

carcinomatous tissue.

•

Lymphangitis carcinomatosa can be due to spread from abdominal and breast cancers as well

as from carcinoma of the lung. The lymphatic vessels become grossly distended and the lungs

become oedematous. The sign can be identical to those seen in interstitial pulmonary

oedema (septal lines, loss of vessel clarity and peribronchial thickening), but if the heart is

normal in size and there is hilar adenopathy and/or lobar consolidation, the diagnosis of

lymphangitis carcinomatosa becomes more certain.

•

The clinical story is very helpful: if the changes are due to pulmonary oedema, the patient

usually complains of sudden onset of breathlessness, whereas the patient with lymphangitis

carcinomatosa gives a story of slowly increasing dyspnoea over the preceding weeks or

months. CT, particularly HRCT, has proven very valuable in demonstrating lymphangitis

carcinomatosa because the appearances, in the correct clinical circumstances, are specific

enough to obviate the need for biopsy.

•

Metastatic neoplasms Metastases from extrathoracic primary tumours may be seen in the lungs, the pleura or

the bones of the thoracic cage or, very rarely, in hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes.

•

Pulmonary metastases : are, typically, spherical and well defined , although irregular borders are occasionally

seen. Usually, they are multiple and vary in size.

•

Metastases have to be almost a centimetre in diameter, or larger, to be visible on a CXR. CT can demonstrate

metastases as small as 3–6 mm. There is, however, a disadvantage attached to the excellent sensitivity of CT.

•

Some small nodules are not metastases, but are benign processes such as tuberculomas or fungal granulomas.

•

Pleural metastases usually give rise to pleural effusion; but metastatic adenocarcinoma can present with diffuse

thickening of the pleura.

•

Metastases to ribs Rib metastases are common with those primary tumours that metastasize to bone, notably

bronchus, breast, kidney, thyroid and prostate .

•

All except prostatic and breast cancers produce mainly or exclusively lytic metastases.

•

With lytic metastases, the most reliable sign is destruction of the cortex, particularly of the upper border of a rib.

•

One should be wary of diagnosing destruction of the lower borders of the posterior portions of the ribs, as these

regions are often ill defined even under normal conditions. When in doubt, it is always wise to compare with the

opposite side. Another pitfall in the diagnosis of rib metastases is that blood vessels in the lungs may cause

confusing opacities. This confusion cannot arise at the edges of the chest where there is no lung projected over

the ribs, so the extreme edge of the chest is a useful place to look for rib destruction.

•

Soft tissue swelling is frequently seen adjacent to the rib deposit, so it is a good rule to look at the outer margin

of the lung for soft tissue swelling as a clue to the presence of rib metastases.

•

Lymphoma The common manifestations of intrathoracic malignant lymphoma are : 1- mediastinal and hilar

adenopathy, and 2- pleural effusion. These features can often be seen on plain films, but CT is much the best

method of confirming or excluding intrathoracic lymph node enlargement.

•

Pulmonary involvement by lymphoma is unusual. It may take the form of large areas of infiltration of the lung

parenchyma, resembling pulmonary pneumonia . As pulmonary infection is a common complication in patients

with malignant lymphoma, it may be impossible to decide on radiological grounds whether the pulmonary

consolidation is due to lymphomatous tissue or to infection. Occasionally, pulmonary lymphoma is seen as one or

more mass lesions, which may cavitate. Pleural masses are a rare feature.

•

Cardiac Disorders

: Imaging techniques : Posteroanterior (PA) chest radiographs (CXRs), sometimes supplemented by lateral chest

films, are useful for assessing the effects of cardiac disease on the lungs and pleural cavities and measuring overall heart size, but

the evaluation of specific chambers is unreliable.

•

Echocardiography is widely used for morphological as well as functional information about the heart. It is excellent for looking at

the heart valves, assessing chamber morphology and volume, determining the thickness of the ventricular wall and diagnosing

intraluminal masses.

•

Doppler ultrasound is used to determine the velocity and direction of blood flow through the heart valves and within cardiac

chambers.

•

Radionuclide examinations are used to assess myocardial blood flow and ventricular contractility, but provide little anatomical

detail.

•

Cardiac computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are now becoming more widely available, providing

both functional and anatomical information in specific indications.

•

Diagnostic information provided by cardiac imaging The structure and mechanical function of the cardiac chambers and valves

•

Myocardial tissue characteristics, e.g. presence of myocardial scar and/or oedema

•

Presence of stress-induced, reversible or irreversible perfusion defects in the myocardium

•

Patency of the coronary arteries

•

Plain chest radiography Plain chest radiographic evidence of heart disease may be given by the size and shape of the heart together

with any cardiac calcification, and by the size of pulmonary vessels and the presence of pulmonary oedema.

•

Heart size and shape The standard plain films for the evaluation of cardiac disease are the PA view and a lateral chest film. The

cardiothoracic ratio (CTR) is a widely used, but crude, method of measuring heart size.

•

The transverse diameter of the heart is normally less than half the internal diameter of the chest when measured on erect PA films .

•

Anteroposterior views magnify the heart, and films taken in supine or semi-erect positions lead to cardiac enlargement.

•

Knowing whether or not the heart has increased in size compared with previous films is often more useful than the CTR in isolation.

It should, however, be realized that the transverse cardiac diameter varies with the phase of respiration and, to some extent, with

the cardiac cycle. Thus, changes in transverse diameter of less than 1.5 cm should be interpreted with caution. An overall increase in

heart size may be due to dilatation of one or more cardiac chambers and/or to pericardial effusion. A potential pitfall is a patient

with a severely

depressed sternum (pectus excavatum) in whom the cardiac outline may appear enlarged and altered in shape from

simple rotation and displacement.

•

Diagnosing specific chamber enlargement on plain films, with the possible exception of dilatation

of the left atrium, is fraught with problems. It is rarely possible to distinguish ventricular

hypertrophy from dilatation by looking at the external contours of the heart.

•

Ventricular dilatation is recognized only as an overall increase in transverse cardiac diameter.

•

Assessment of atrial size on the CXR, particularly left atrial enlargement is easier: the right border

of an enlarged left atrium is visible as a double contour adjacent to the right heart border, usually

within the main cardiac shadow.

•

The left atrial appendage, when dilated, is seen as a bulge below the main pulmonary artery on the

PA view.

•

Right atrial enlargement causes an increase in the curvature of the right heart border and is often

accompanied by enlargement of the superior vena cava.

•

The only plain film information directly relating to morphology of the valves is calcification, which

is best evaluated at echocardiography. Calcification of the mitral valve ring is occasionally seen on

CXRs in the elderly, and is often associated with mild mitral regurgitation.

•

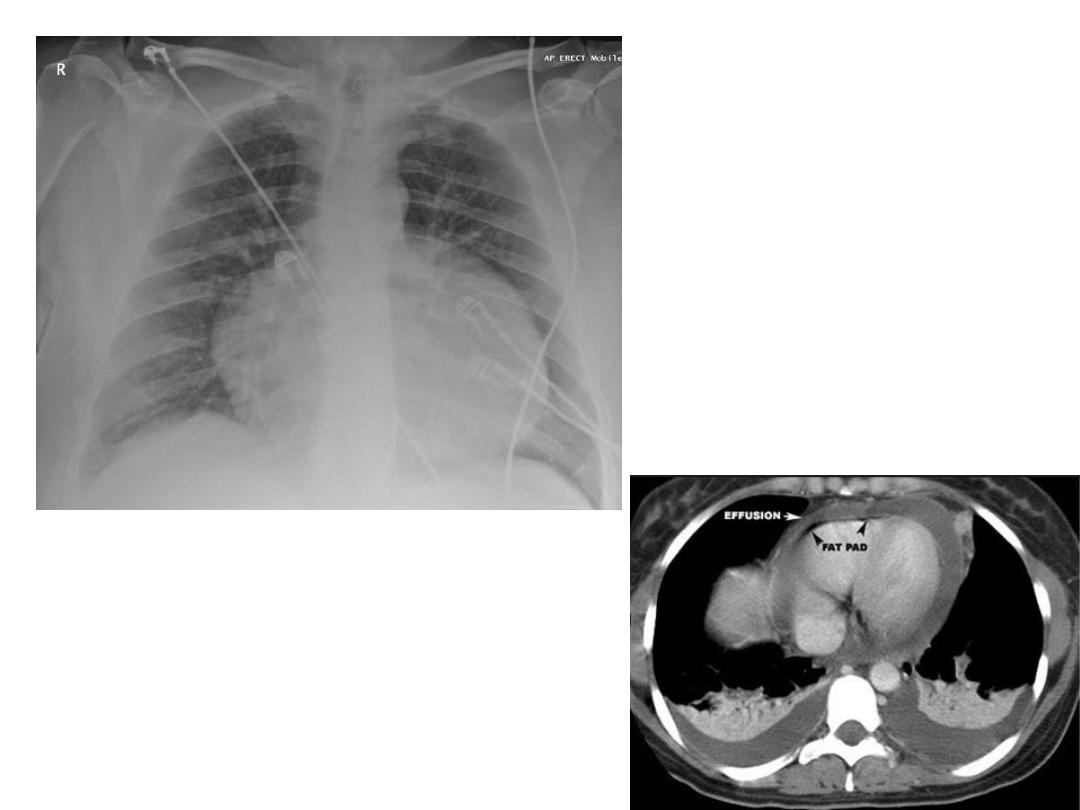

It is unusual to be able to diagnose a pericardial effusion from the plain CXR. Indeed, a patient may

have sufficient pericardial fluid to cause life-threatening tamponade, but only have mild cardiac

enlargement with an otherwise normal contour. A marked increase in the transverse cardiac

diameter within a week or two, particularly if no pulmonary oedema occurs, is virtually diagnostic

of the condition. Pericardial effusion should also be considered when the heart is greatly enlarged

and there are no features to suggest specific chamber enlargement .

•

Extensive

pericardial calcification is seen in patients with constrictive

pericarditis.

•

Main pulmonary artery and pulmonary vasculature The CXR provides a simple method of

assessing the size of the main pulmonary artery and the pulmonary vasculature. Even though it is

not possible to measure the true diameter of the main pulmonary artery on plain film, there are

degrees of bulging that permit one to say that it is indeed enlarged .

•

The assessment of the hilar vessels can be more objective since the diameter of the right lower

lobe artery can be measured: the diameter at its midpoint is normally between 9 and 16 mm.

•

The size of the vessels within the lungs reflects pulmonary blood flow.

• Increased pulmonary blood flow

due to left to right shunts

Atrial septal defect,

ventricular septal defect and patent ductus arteriosus are the common anomalies

in which there is shunting of blood from the systemic to the pulmonary circuits (so-

called left to right shunts), thereby increasing pulmonary blood flow. In patients

with a haemodynamically significant left to right shunt (2 : 1 or more), all the

vessels from the main pulmonary artery to the periphery of the lungs are large. This

radiographic appearance is sometimes called pulmonary plethora.

• Pulmonary arterial hypertension The conditions that cause significant pulmonary

arterial hypertension : Various lung diseases (e.g. cor pulmonale), Pulmonary

emboli, Mitral valve disease, Left to right shunts, Idiopathic pulmonary

hypertension, all increase the resistance of blood flow through the lungs.

• Pulmonary arterial hypertension has to be severe before it can be diagnosed on

plain films.

• The CXR features are 1- enlargement of the pulmonary artery and hilar arteries, the

vessels within the lung being normal or small.

2- The reason for pulmonary arterial hypertension may be visible on CXR, such as

radiologically visible lung disease in cor pulmonale.

• Pulmonary venous hypertension Mitral valve disease, and left ventricular failure

are the common causes of elevated pulmonary venous pressure.

• In the normal upright person, the lower zone vessels are larger than those in the

upper zones. In raised pulmonary venous pressure, the upper zone vessels enlarge

and in severe cases become larger than those in the lower zones. Eventually,

pulmonary oedema will supervene and may obscure the blood vessels.

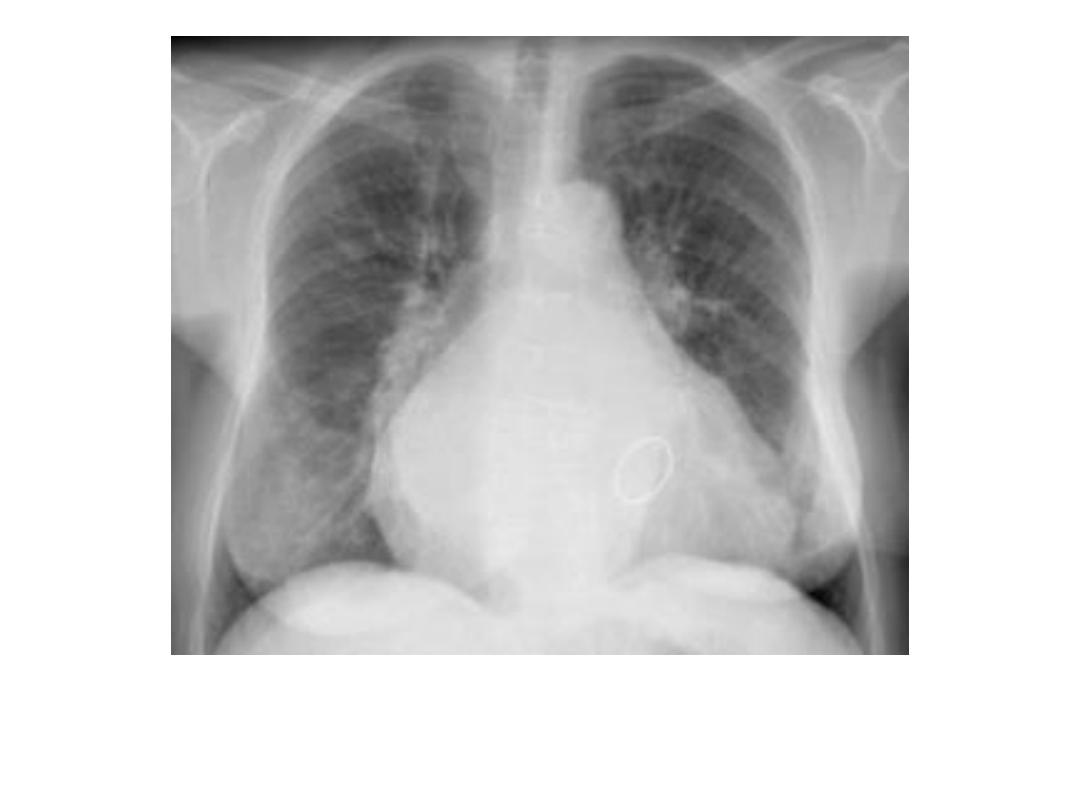

• Pulmonary oedema There are two radiographic patterns of cardiogenic pulmonary

oedema: alveolar and interstitial. As oedema initially collects in the interstitial

tissues of the lungs, all patients with alveolar oedema also have interstitial oedema.

•

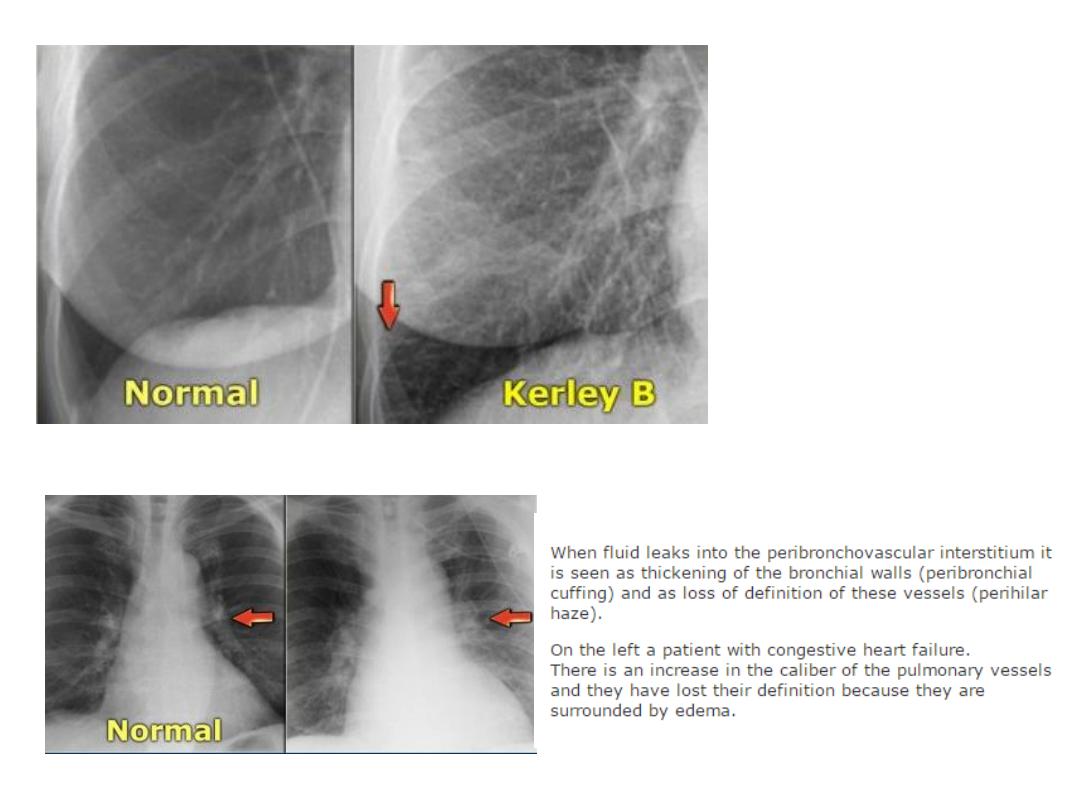

Interstitial oedema 1-There are many septa in the

lungs which are invisible on the

normal CXR because they consist of little more than a sheet of connective tissue

containing very small blood and lymph vessels. When thickened by oedema, the

peripherally located septa may be seen as lines, known as Kerley B lines, They are

horizontal lines, never more than 2 cm long, seen laterally in the lower zones. They

reach the lung edge and are, therefore, readily distinguished from blood vessels,

which never extend into the outer centimetre of the lung.

2- Another sign of interstitial oedema is that the outline of the blood vessels may

become indistinct owing to oedema collecting around them.

3- Fissures may appear thickened because oedema may collect against them.

•

Alveolar oedema is a more severe form of

oedema in which the fluid collects in the

alveoli. It is almost always bilateral, involving all the lobes. The pulmonary

opacification is usually maximal close to the hila and fades out peripherally, leaving

a relatively clear zone peripherally that may contain septal lines. This pattern of

oedema is sometimes referred to as the ‘butterfly’ or ‘bat’s wing’ pattern.

• Positron emission tomography can provide cross-sectional images of the patient’s

anatomy after injection of either a flow tracer or a radionuclide, which is an

analogue of glucose (18F-fluorodeoxyglucose), thus providing information on the

myocardial metabolism. PET can identify areas of viable, non-viable and hibernating

myocardium.

•

Computed tomography Standard CT plays little part in the management of intracardiac

disorders.

•

Pericardial effusions and cardiac tumours are recognizable, but they are usually equally well

or better seen at ultrasound.

•

Modern multidetector CT scanners can produce high resolution images of the coronary

arteries by applying electrocardiographic gating (cardiac CT). In

•

general a cardiac CT study includes two scans:

1- non-contrast scan for the measurement of coronary : calcification (coronary artery calcium

score). The amount of calcification can be used to determine who should receive

prophylactic treatment for atheroma in the hope of preventing future cardiac events.

2- contrast-enhanced scan (coronary CT angiography) for the study of the coronary arterial

tree, cardiac chambers and valves together with the great vessels .

•

The main focus of coronary CT angiography is the noninvasive identification of coronary

artery stenosis in patients with suspected ischaemic chest pain.

•

Magnetic resonance imaging Gating of the standard MRI sequences using an

electrocardiogram .

•

Myocardial perfusion may be evaluated after injection of a contrast agent (gadolinium) as

regions of reduced perfusion. The ability to characterize tissues allows the identification of

myocardial scar tissue, shown as areas where gadolinium accumulates on delayed imaging

due a damaged capillary network.

•

Information available from cardiac gated MRI: 1- Anatomy of complex congenital heart

disease 2- Details of myocardial thickness, morphology and function. 3- Myocardial

perfusion. 4- Tissue characterization. 5- Myocardial oedema. 6- Valve disease. 7- Pericardial

disease. 8- Intracardiac tumours, which can be shown with great precision, better in many

cases than with ultrasound.

•

Heart failure : One or more of the following signs of heart failure may be seen on CXR : 1-

Cardiac enlargement. 2- Evidence of raised pulmonary venous pressure, namely enlargement

of the vessels in the upper zones of the lung.

3- Evidence of pulmonary oedema. 4- Pleural effusions, which are usually bilateral, often larger

on the right than the left, and if unilateral are almost always right-sided. (In acute left

ventricular failure, small effusions are seen in the costophrenic angles running up the lateral

chest wall.)

•

Cardiac ultrasound allows ventricular volumes and ejection fractions to be measured with

considerable accuracy, as well as enabling valve gradients and degrees of regurgitation to be

assessed. It is, therefore, an excellent diagnostic tool in evaluating heart failure.

•

Cardiac MRI plays an important role in the diagnosis and characterization of heart failure. MRI

shows cardiac morphology, function and viability. Acute tissue and perfusion injuries (like

oedema and necrosis) can be detected. MRI gives important information in non-ischaemic

heart failure by demonstrating scarring or infiltrative myocardial disease.

•

Ischaemic heart disease Most patients with angina have a normal CXR and a normal

echocardiogram. Patients with previous or new myocardial infarction may have a normal

echocardiogram, but usually show evidence of reduced wall movement in the region of

infarction, or dilatation of the whole of the left ventricle.

•

Most patients with myocardial infarction have a normal CXR, but severe ischaemic damage to

the myocardium may result in one or more of the following signs:

1-Cardiac enlargement and aneurysm formation. 2- Signs of raised pulmonary venous

pressure and pulmonary oedema.

•

Myocardial perfusion scintigraphy allows one to determine areas of myocardial ischaemia, and

from their location it is sometimes possible to predict which of the coronary arteries is

compromised.

•

On cardiac MRI, ischaemic areas are seen on the stress scan as areas of reduced contrast uptake

after injection of gadolinium. Infarcted areas will show accumulation of gadolinium on delayed

images due to damage of the intramyocardial capillary bed and consequent reduced clearance of

the contrast. This ability to distinguish ischaemia and infarction may be useful when planning

cardiac surgery.

•

The state of the coronary arteries can be determined by coronary CT angiography , or conventional

coronary angiography .

•

Coronary CT angiography is preferred in patients with a low probability of disease based on clinical

findings (e.g. chest pain with atypical features, lack of cardiovascular risk factors). In these

circumstances, a non-invasive test is preferable in order to rule out the presence of coronary

stenoses.

•

In patients with a high probability of ischaemic heart disease (e.g. symptoms typically related to

exercise) or with acute myocardial infarction, conventional coronary angiography is preferred with a

view to performing coronary angioplasty.

•

Hypertensive heart disease and other myocardial diseases Ventricular hypertrophy without

dilatation does not cause recognizable abnormality on a CXR. Therefore, in systemic hypertension

and various forms of cardiomyopathy, the CXR only becomes abnormal once ventricular dilatation

has taken place.

•

If there is a rise in left ventricular end diastolic pressure, moderate left atrial enlargement and signs

of elevation of pulmonary venous pressure may be seen. The shape of the heart is the same

regardless of the cause of the myocardial disorder. However, the aorta may enlarge in systemic

hypertension.

•

Echocardiography and cardiac MRI in systemic hypertension show symmetrical increase in the

thickness of the left ventricular wall with a normal aortic valve. Once decompensation occurs, the

cavity will enlarge.

•

Cardiac MRI plays a pivotal role in confirming the diagnosis and determining the extent of

involvement shown by myocardial oedema and possibly necrosis (scar)

•

Coronary artery disease can be ruled out by conventional angiography or coronary CT angiography.

• Pericardial effusion : is recognized on echocardiography as an echo-free space

between the walls of the cardiac chambers and the pericardium . Quantities as

small as 20–50 mL of pericardial fluid can be diagnosed by ultrasound. CT also

readily demonstrates pericardial fluid.

• The nature of the fluid cannot usually be ascertained, and needle aspiration of

the fluid may be necessary; such aspiration is best performed under ultrasound

guidance.

• Left atrial myxoma and other intracardiac masses : Intracardiac tumours are

rare: left atrial myxoma is the most frequently encountered.

• It is a benign tumour that usually arises in the interatrial septum or in the wall

of the left atrium. As it enlarges, it becomes pedunculated to float in the left

atrial cavity. The myxoma may, therefore, interfere with the function of the

mitral valve and mimic mitral stenosis or regurgitation.

• Echocardiography has proved to be an excellent tool for its diagnosis by

showing a mass of echoes in the cavity of the left atrium, which usually

prolapses into the mitral valve orifice during diastole.

• Cardiac MRI and CT have also proved to be excellent methods of

demonstrating left atrial myxoma and other intracardiac tumours.

Emphysema

Bronchiectasis

Hyaline membrane disease

ARDS

Hampton hump

Pulmonary embolism

CA bronchus

Lymphangitis carcinomatosa

PET CT scan, recurrent rt. Side CA bronchus

after pneumonectomy site at bronchial

stump

lymphoma

Left atrial enlargement

PAH

Interstial PE

Alveolar PE

Pericardial effusion

THANK YOU