1

Classification of organisms microbiology

Carl Woese devised three classification groups called domain. A domain is larger than a

kingdom

Domains

· Eubacteria: Bacteria that have peptidoglycan cell walls. (Peptidoglycan is the molecular

structure of the cell walls of eubacteria which consists of Nacetyglucosamine, N-

acetylmuramic acid, tetrapeptide, side chain and murein).

· Archaea: Prokaryotes that do not have peptidoglycan cell walls

· Eucarya: Organisms from the following kingdoms:

Kingdoms

· Protista: Examples- Algae, protozoa.

· Fungi: Examples- one-celled yeasts, multicellular molds and mushrooms.

· Plantae: Examples- moss, conifers, ferns, flowering plant, algae.

· Animalia: Examples- insects, worms, sponges and vertebrates.

Host-pathgen relations

Introduction:

The pathogenesis of bacterial infection includes initiation of the infectious process and the

mechanisms that lead to the development of signs and symptoms of disease. Characteristics

of bacteria that are pathogens include transmissibility, adherence to host cells, invasion of

host cells and tissues, toxigenicity, and ability to evade the host's immune system. Many

infections caused by bacteria that are commonly considered to be pathogens are inapparent

or asymptomatic.

Adherence (adhesion, attachment):

The process by which bacteria stick to the surfaces of host cells. Once bacteria have entered

the body, adherence is a major initial step in the infection process.

Carrier: A person or animal with asymptomatic infection that can be transmitted to another

susceptible person or animal.

Infection: Multiplication of an infectious agent within the body. Multiplication of the bacteria

that are part of the normal flora of the gastrointestinal tract, skin, etc, is generally not

considered an infection; on the other hand, multiplication of pathogenic bacteria (eg,

Salmonella species)—even if the person is asymptomatic––is deemed an infection.

2

Invasion: The process whereby bacteria, animal parasites, fungi, and viruses enter host cells or

tissues and spread in the body.

Nonpathogen: A microorganism that does not cause disease; may be part of the normal flora.

Opportunistic pathogen: An agent capable of causing disease only when the host's resistance

is impaired (ie, when the patient is "immunocompromised").

Pathogen: A microorganism capable of causing disease.

Pathogenicity: The ability of an infectious agent to cause disease.

Toxigenicity: The ability of a microorganism to produce a toxin that contributes to the

development of disease.

Virulence: The quantitative ability of an agent to cause disease. Virulent agents cause disease

when introduced into the host in small numbers. Virulence involves invasion and toxigenicity

Normal Microbial Flora of the Human Body

The term "normal microbial flora" denotes the population of microorganisms that inhabit the

skin and mucous membranes of healthy normal persons. It is doubtful whether a normal viral

flora exists in humans.

The skin and mucous membranes always harbor a variety of microorganisms that can be

arranged into two groups: (1) The resident

flora consists of relatively fixed types of microorganisms regularly found in a given area at a

given age; if disturbed, it promptly reestablishes itself. (2) The transient flora consists of

nonpathogenic or potentially pathogenic microorganisms that inhabit the skin or mucous

membranes for hours, days, or weeks; it is derived from the environment, does not produce

disease, and does not establish itself permanently on the surface. Members of the transient

flora are generally of little significance so long as the normal resident flora remains intact.

However, if the resident flora is disturbed, transient microorganisms may colonize, proliferate,

and produce disease.

Transmission of Infection

—

Microorganisms can be transmitted from environment (human or animals) and affected

another host by aerosol route, oral route, or nosocomial infection and urogenital route these

processes can be occurred by several ways:

—

1- direct contact from infected animal to susceptible person (zoonotic disease). Like

Bacillus anthracis (caused anthrax).

3

2- rodents borne disease like Yersinia pestis.

3- nosocomial disease by hand personal.

The Infectious Process

—

Once in the body, bacteria must attach or adhere to host cell, usually epithelial cells. After

the bacteria have established a primary site of infection, they multiply and spread directly

through tissues or via the lymphatic system to the bloodstream. This infection (bacteremia)

can be transient or persistent. Bacteremia allows bacteria to spread widely in the body and

permits them to reach tissues particularly suitable for their multiplication.

—

Pneumococcal pneumonia is an example of the infectious process. S pneumoniae can be

cultured from the nasopharynx of 5–40% of healthy people. Occasionally, pneumococci

from the nasopharynx are aspirated into the lungs

Adherence Factors

Once bacteria enter the body of the host, they must adhere to cells of a tissue surface. If they

did not adhere, they would be swept away by mucus and other fluids that bathe the tissue

surface. Adherence, which is only one step in the infectious process, is followed by

development of microcolonies and subsequent steps in the pathogenesis of infection.

The interactions between bacteria and tissue cell surfaces in the adhesion process are

complex. Several factors play important roles: surface hydrophobicity and net surface charge,

binding molecules on bacteria (ligands), and host cell receptor interactions. Bacteria and host

cells commonly have net negative surface charges and, therefore, repulsive electrostatic

forces. These forces are overcome by hydrophobic and other more specific interactions

between bacteria and host cells.

Bacteria also have specific surface molecules that interact with host cells. Many bacteria have

pili, hair-like appendages that extend from the bacterial cell surface and help mediate

adherence of the bacteria to host cell surfaces. For example, some E coli strains have type 1

pili, which adhere to epithelial cell receptors containing D-mannose; adherence can be

blocked in vitro by addition of D-mannose to the medium. E coli organisms that cause urinary

tract infections commonly do not have D-mannose-mediated adherence but have P-pili, which

attach to a portion of the P blood

—

Therefore the important adherence factors include:

capsule

2-pili like P pili of E.coli

interaction between bacterial cell components (ligands) and specific host receptors.

different charges between bacterial surface and host cell surface (electrostatic force)

4

Invasion of Host Cells & Tissues

—

For many disease-causing bacteria, invasion of the host's epithelium is central to the

infectious process. Some bacteria (eg, salmonella species) invade tissues through the

junctions between epithelial cells. Other bacteria (eg, yersinia species, N gonorrhoeae,

Chlamydia trachomatis) invade specific types of the host's epithelial cells and may

subsequently enter the tissue. Once inside the host cell, bacteria may remain enclosed in a

vacuole composed of the host cell membrane, or the vacuole membrane may be dissolved

and bacteria may be dispersed in the cytoplasm. Some bacteria (eg, shigella species)

multiply within host cells, whereas other bacteria do not.

—

"Invasion" is the term commonly used to describe the entry of bacteria into host cells,

implying an active role for the organisms and a passive role for the host cells. In many

infections, the bacteria produce virulence factors that influence the host cells, causing

them to engulf (ingest) the bacteria. The host cells play a very active role in the process.

—

Toxin production and other virulence properties are generally independent of the ability of

bacteria to invade cells and tissues. For example, Corynebacterium diphtheriae is able to

invade the epithelium of the nasopharynx and cause symptomatic sore throat even when

the C diphtheriae strains are nontoxigenic.

—

—

M cells normally sample antigens and present them to macrophages in the submucosa.

Shigellae are phagocytosed by the M cells, pass through the M cells, and escape killing by

macrophages.

—

L monocytogenes from the environment is ingested in food. Presumably, the bacteria

adhere to and invade the intestinal mucosa, reach the bloodstream, and disseminate. The

pathogenesis of this process has been studied in vitro. L monocytogenes adheres to and

readily invades macrophages and cultured undifferentiated intestinal cells. The listeriae

induce engulfment by the host cells.

—

Toxins

—

Toxins produced by bacteria are generally classified into two groups: exotoxins and

endotoxins.

—

Exotoxins

—

Many gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria produce exotoxins of considerable medical

importance. Some of these toxins have had major roles in world history. For example,

tetanus caused by the toxin of C tetani killed as many as 50,000 soldiers of the Axis powers

in World War II. Many exotoxins consist of A and B subunits. The B subunit generally

5

mediates adherence of the toxin complex to a host cell and aids entrance of the exotoxin

into the host cell. The A subunit provides the toxic activity.

—

C botulinum causes botulism. It is found in soil or water and may grow in foods (canned,

vacuum-packed, etc) if the environment is appropriately anaerobic. An exceedingly potent

toxin (the most potent toxin known) is produced. It is heat-labile and is destroyed by

sufficient heating.

Some S aureus strains growing on mucous membranes or in wounds, elaborate toxic shock

syndrome toxin-1 (TSST-1), which causes toxic shock syndrome. The illness is characterized

by shock, high fever, and a diffuse red rash that later desquamates; multiple other organ

systems are involved as well. TSST-1 is a super antigen and stimulates lymphocytes to

produce large amounts of IL-1 and TNF. The major clinical manifestations of the disease

appear to be secondary to the effects of the cytokines. TSST-1 may act synergistically with

low levels of lipopolysaccharide to yield the toxic effect.

Negative Bacteria

-

Lipopolysaccharides of Gram

The lipopolysaccharides (LPS, endotoxin) of gram-negative bacteria are derived from

cell walls and are often liberated when the bacteria lyse. The substances are heat-

stable, have molecular weights between 3000 and 5000 (lipooligosaccharides, LOS) and

several million (lipopolysaccharides), and can be extracted (eg, with phenol-water).

The pathophysiologic effects of LPS are similar regardless of their bacterial origin

except for those of bacteroides species, which have a different structure and are less

toxic. LPS in the bloodstream is initially bound to circulating proteins which then

interact with receptors on macrophages and monocytes and other cells of the

reticuloendothelial system. IL-1, TNF, and other cytokines are released, and the

complement and coagulation cascades are activated. The following can be observed

clinically or experimentally: fever, leukopenia, and hypoglycemia; hypotension and

shock resulting in impaired perfusion of essential organs (eg, brain, heart, kidney);

intravascular coagulation; and death from massive organ dysfunction.

—

6

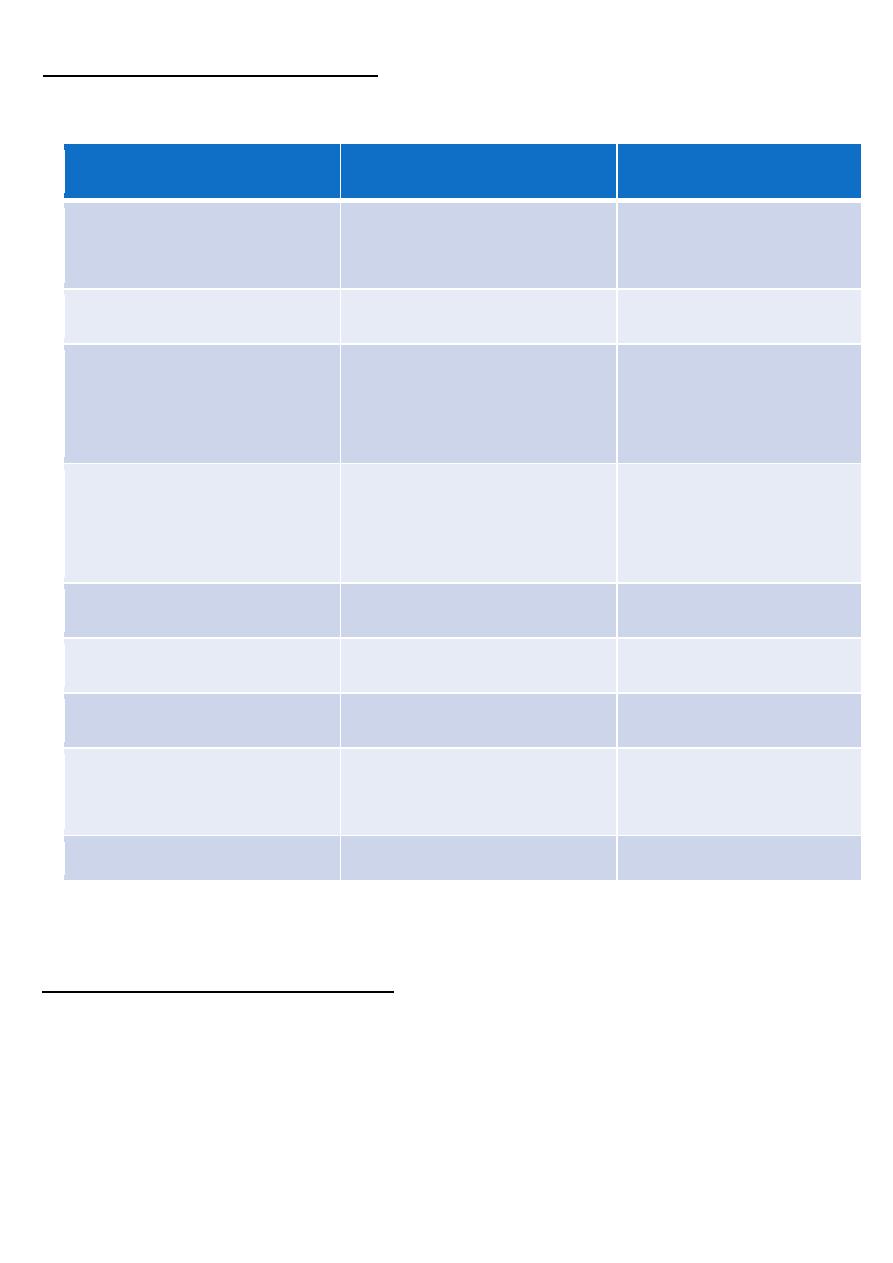

Differences between exo and end

endotoxin

exotoxin

proberty

Bacterial

chromosome

Plasmid or

bacteriophage

Gene location

lps

proteins

composition

Non specific fever

and shock

specific

Action

Stable at 100 C° for

1 hr

Labile destroyed at

60C°

Heat stability

No

yes

diffusibility

Weak

Strong

Antigenicity

Weak

Strong

Toxicity

no

Yes

Convertibility to

toxoid

Gram -ve

Mainly G+ve

Produced by

—

Peptidoglycan of Gram-Positive Bacteria

—

The peptidoglycan of gram-positive bacteria is made up of cross-linked macromolecules

that surround the bacterial cells. Vascular changes leading to shock may also occur in

infections due to gram-positive bacteria that contain no LPS. Gram-positive bacteria have

considerably more cell wall-associated peptidoglycan than do gram-negative bacteria.

Peptidoglycan released during infection may yield many of the same biologic activities as

LPS, though peptidoglycan is invariably much less potent than LPS.

7

—

Enzymes

—

Many species of bacteria produce enzymes that are not intrinsically toxic but do play

important roles in the infectious process for examples : -

—

Tissue-Degrading Enzymes

—

Many bacteria produce tissue-degrading enzymes. The best-characterized are enzymes

from C perfringens), S aureus , group A streptococci , and, to a lesser extent, anaerobic

bacteria. The roles of tissue-degrading enzymes in the pathogenesis of infections appear

obvious but have been difficult to prove, especially those of individual enzymes. For

example, antibodies against the tissue-degrading enzymes of streptococci do not modify

the features of streptococcal disease.

—

In addition to lecithinase, C perfringens produces the proteolytic enzyme collagenase,

which degrades collagen, the major protein of fibrous connective tissue, and promotes

spread of infection in tissue.

—

—

S aureus produces coagulase, which works in conjunction with serum factors to coagulate

plasma. Coagulase contributes to the formation of fibrin walls around staphylococcal

lesions, which helps them persist in tissues. Coagulase also causes deposition of fibrin on

the surfaces of individual staphylococci, which may help protect them from phagocytosis or

from destruction within phagocytic cells.

—

Hyaluronidases are enzymes that hydrolyze hyalouronic acid, a constituent of the ground

substance of connective tissue. They are produced by many bacteria (eg, staphylococci,

streptococci, and anaerobes) and aid in their spread through tissues.

—

IgA1 Proteases

—

Immunoglobulin A is the secretory antibody on mucosal surfaces. It has two primary forms,

IgA1 and IgA2, that differ near the center, or hinge, region of the heavy chains of the

molecules. IgA1 has a series of amino acid in the hinge region that are not present in IgA2.

Some bacteria that cause disease produce enzymes, IgA1 proteases, that split IgA1 at

specific proline-threonine or proline-serine bonds in the hinge region and inactivate its

antibody activity. IgA1 protease is an important virulence factor of the pathogens N

gonorrhoeae, N meningitidis, H influenzae, and S pneumoniae. .

—

—

—

8

—

Antiphagocytic Factors

—

Many bacterial pathogens are rapidly killed once they are ingested by polymorphonuclear

cells or macrophages. Some pathogens evade phagocytosis or leukocyte microbicidal

mechanisms by adsorbing normal host components to their surfaces. For example, S

aureus has surface protein A, which binds to the Fc portion of IgG. Other pathogens have

surface factors that impede phagocytosis—eg, S pneumoniae, N meningitidis; many other

bacteria have polysaccharide capsules. S pyogenes (group A streptococci) has M protein. N

gonorrhoeae (gonococci) has pili. Most of these antiphagocytic surface structures show

much antigenic heterogeneity. For example, there are more than 90 pneumococcal

capsular polysaccharide types and more than 80 M protein types of group A streptococci.

Antibodies against one type of the antiphagocytic factor (eg, capsular polysaccharide, M

protein) protect the host from disease caused by bacteria of that type but not from those

with other antigenic types of the same factor.

—

A few bacteria (eg, capnocytophaga and bordetella) produce soluble factors or toxins that

inhibit chemotaxis by leukocytes and thus evade phagocytosis by a different mechanism.

—

Intracellular Pathogenicity

—

Some bacteria (eg, M tuberculosis, brucella species, and legionella species) live and grow in

the hostile environment within polymorphonuclear cells, macrophages, or monocytes. The

bacteria accomplish this feat by several mechanisms: They may avoid entry into

phagolysosomes and live within the cytosol of the phagocyte; they may prevent

phagosome-lysosome fusion and live within the phagosome; or they may be resistant to

lysosomal enzymes and survive within the phagolysosome.

—

Antigenic Heterogeneity

—

The surface structures of bacteria (and of many other microorganisms) have considerable

antigenic heterogeneity. Often these antigens are used as part of a serologic classification

system for the bacteria. The classification of the 2000 or so different salmonellae is based

principally on the types of the O (lipopolysaccharide side chain) and H (flagellar) antigens.

Similarly, there are more than 100 E coli O types and more than 100 E coli K (capsule)

types. The antigenic type of the bacteria may be a marker for virulence, related to the

clonal nature of pathogens .

—