Talaro−Talaro: Foundations

in Microbiology, Fourth

Edition

16. Immunization and

Immune Assays

Text

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2002

476

n expanded knowledge of immune function has yielded sig-

nificant breakthroughs in medical technology for manipulat-

ing and monitoring the immune system. One of the most prac-

tical benefits of immunology is administering vaccines and other

immune treatments against common infectious diseases such as hep-

atitis and tetanus that once caused untold sickness and death. Another

valuable application of this technology is testing the blood for signs of

infection or disease. It is routine medical practice to diagnose such in-

fections as HIV, syphilis, hepatitis B, and rubella by means of immuno-

logic analysis. Both separately and in combination, these methods

have made sweeping contributions to individual and community health

by improving diagnosis and treatment, and controlling the spread of

disease. Many hopes for the survival of humankind lie in our ability to

harness the amazing workings of the immune system.

Chapter Overview

• Discoveries in basic immune function have created powerful medical

tools to artificially induce protective immunities and to determine the

status of the immune system.

• Immunization may be administered by means of passive and active

methods.

• Passive immunity is acquired by infusing antiserum taken from other

patients’ blood that contains high levels of protective antibodies. This

form of immunotherapy is short-lived.

• Active methods involve administering a vaccine against an infectious

agent that may be encountered in the future. This form of protection

provides a longer-lived immunity.

• Vaccines contain some form of microbial antigen that has been altered

so that it stimulates a protective immune response without causing the

disease.

• Vaccines can be made from whole dead or live cells and viruses, parts

of cells or viruses, or by recombinant DNA techniques.

• Reactions between antibodies and antigens provide specific and

sensitive tests that can be used in diagnosis of disease and

identification of pathogens.

• Serology involves the testing of a patient’s blood serum for antibodies

that can indicate a current or past infection and the degree of immunity.

• Tests that produce visible interactions of antibodies and antigens

include agglutination, precipitation, and complement fixation.

A

• Assays can be used to separate antigens and antibodies and visualize

them with radioactivity or fluorescence. These include

immunoelectrophoresis, the Western blot, and direct and indirect

immunoassays.

Practical Applications of Immunologic

Function

A knowledge of the immune system and its responses to antigens

has provided extremely valuable biomedical applications in two

major areas: (1) use of antiserum and vaccination to provide artifi-

cial protection against disease and (2) diagnosis of disease through

immunologic testing.

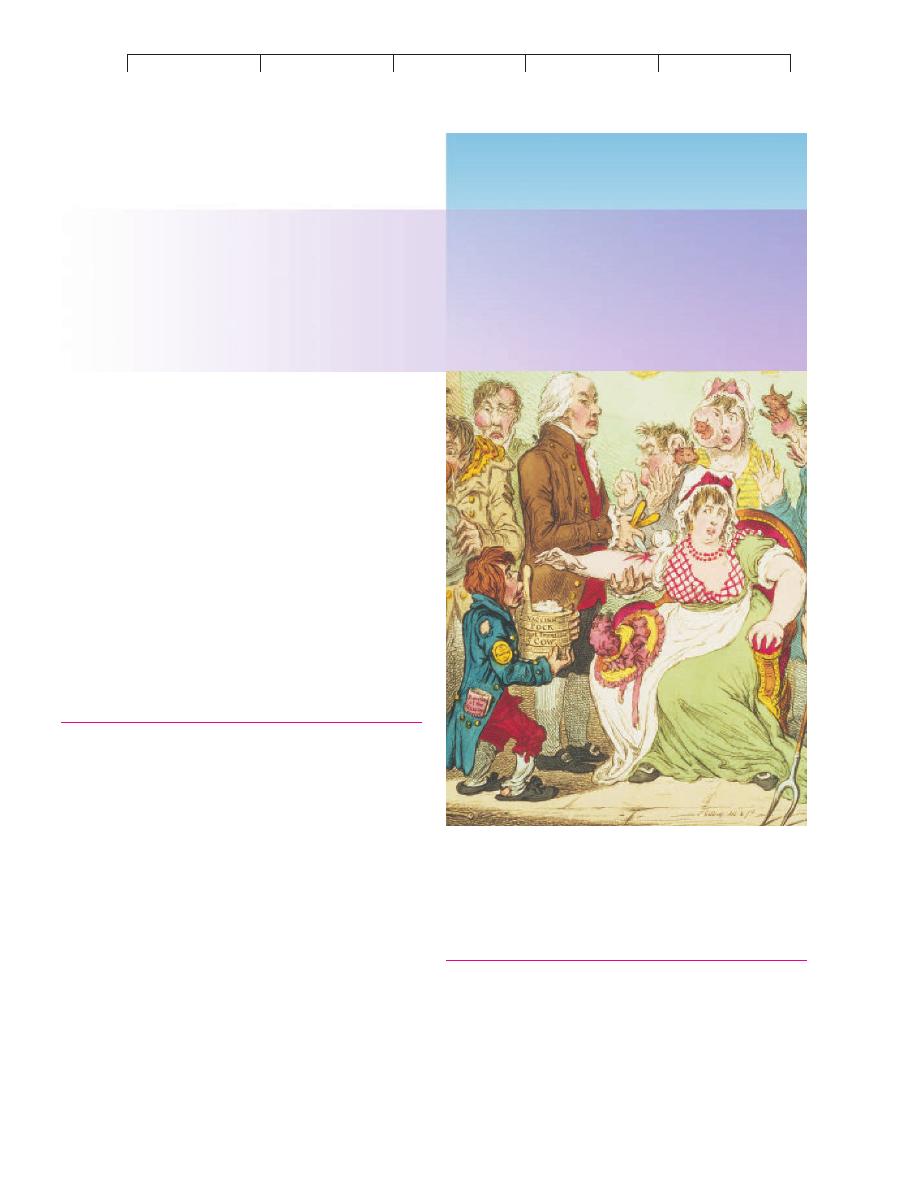

Detail from “The Cowpock,” an 1808 etching that caricatured the worst fears

of the English public concerning Edward Jenner’s smallpox vaccine.

Immunization and

Immune Assays

CHAPTER

16

Talaro−Talaro: Foundations

in Microbiology, Fourth

Edition

16. Immunization and

Immune Assays

Text

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2002

Practical Applications of Immunologic Function

477

IMMUNIZATION: METHODS OF MANIPULATING

IMMUNITY FOR THERAPEUTIC PURPOSES

The concept of artificially induced immunity was introduced in

chapters 14 and 15. Methods that actively or passively immunize

people are widely used in disease prevention and treatment. In the

case of passive immunization, a patient is given preformed anti-

bodies, which is actually a form of

immunotherapy. In the case of

active immunization, a patient is vaccinated with a microbe or its

antigens, providing a form of advance protection.

Immunotherapy: Artificial Passive Immunity

The first attempts at passive immunization involved the transfusion

of horse serum containing antitoxins to prevent tetanus and to treat

patients exposed to diphtheria. Since then, antisera from animals

have been replaced with products of human origin that function

with various degrees of specificity.

Immune serum globulin (ISG),

sometimes called

gamma globulin, contains immunoglobulin ex-

tracted from the pooled blood of at least 1,000 human donors. The

method of processing ISG concentrates the antibodies to increase

potency and eliminates potential pathogens (such as the hepatitis B

and HIV viruses). It is a treatment of choice in preventing measles

and hepatitis A and in replacing antibodies in immunodeficient pa-

tients. Most forms of ISG are injected intramuscularly to minimize

adverse reactions, and the protection it provides lasts 2 to 3 months.

A preparation called

specific immune globulin (SIG) is de-

rived from a more defined group of donors. Companies that prepare

SIG obtain serum from patients who are convalescing and in a hy-

perimmune state after such infections as pertussis, rabies, tetanus,

chickenpox, and hepatitis B. These globulins are preferable to ISG

because they contain higher titers of specific antibodies obtained

from a smaller pool of patients. Although useful for prophylaxis in

persons who have been exposed or may be exposed to infectious

agents, these sera are often limited in availability.

When a human immune globulin is not available, antisera

and antitoxins of animal origin can be used. Sera produced in

horses are available for diphtheria, botulism, and spider and snake

bites. Unfortunately, the presence of horse antigens can stimulate

allergies such as serum sickness or anaphylaxis (see chapter 17).

Although donated immunities only last a relatively short time, they

act immediately and can protect patients for whom no other useful

medication or vaccine exists.

Artificial Active Immunity: Vaccination

Active immunity can be conferred artificially by

vaccination—

exposing a person to material that is antigenic but not pathogenic.

The discovery of vaccination was one of the farthest reaching and

most important developments in medical science (Historical High-

lights 16.1). The basic principle behind vaccination is to stimulate

HISTORICAL HIGHLIGHTS

16.1

The Lively History of Active Immunization

The basic notion of immunization has existed for thousands of years. It

probably stemmed from the observation that persons who had recovered

from certain communicable diseases rarely if ever got a second case. Un-

doubtedly, the earliest crude attempts involved bringing a susceptible

person into contact with a diseased person or animal. The first recorded

attempt at immunization occurred in sixth century China. It consisted of

drying and grinding up smallpox scabs and blowing them with a straw

into the nostrils of vulnerable family members. By the tenth century, this

practice had changed to the deliberate inoculation of dried pus from the

smallpox pustules of one patient into the arm of a healthy person, a tech-

nique later called

variolation (variola is the smallpox virus). This

method was used in parts of the Far East for centuries before Lady Mary

Montagu brought it to England in 1721. Although the principles of the

technique had some merit, unfortunately, many recipients and their con-

tacts died of smallpox. This outcome vividly demonstrates a cardinal rule

for a workable vaccine: It must contain an antigen that will provide pro-

tection but not cause the disease. Variolation was so controversial that

any English practitioner caught doing it was charged with a felony.

Eventually, this human experimentation paved the way for the first

really effective vaccine, developed by the English physician Edward

Jenner in 1796 (see chapter 24). Jenner conducted the first scientifically

controlled study, one that had a tremendous impact on the advance of

medicine. His work gave rise to the words

vaccine and vaccination

(from L.,

vacca, cow), which now apply to any immunity obtained by in-

oculation with selected antigens. Jenner was inspired by the case of a

dairymaid who had been infected by a pustular infection called cowpox.

This is a related virus that afflicts cattle but causes a milder condition in

humans. She explained that she and other milkmaids had remained free

of smallpox. Other residents of the region expressed a similar confidence

in the cross-protection of cowpox. To test the effectiveness of this new

vaccine, Jenner prepared material from human cowpox lesions and inoc-

ulated a young boy. When challenged 2 months later with an injection of

crusts from a smallpox patient, the boy proved immune.

Jenner’s discovery—that a less pathogenic agent could confer

protection against a more pathogenic one—is especially remarkable in

view of the fact that microscopy was still in its infancy and the nature of

viruses was unknown. At first, the use of the vaccine was regarded with

some fear and skepticism (see chapter opening illustration). When Jen-

ner’s method proved successful and word of its significance spread, it

was eventually adopted in many other countries. Eventually, the original

virus mutated into a unique strain (

vaccina virus) that was the modern ba-

sis of the vaccine. Now that smallpox is no longer a threat, smallpox vac-

cination has been essentially discontinued in most areas.

Other historical developments in vaccination included using heat-

killed bacteria in vaccines for typhoid fever, cholera, and plague and

techniques for using neutralized toxins for diphtheria and tetanus.

Throughout the history of vaccination, there have been vocal opponents

and minimizers, but numbers do not lie. Whenever a vaccine has been in-

troduced, the prevalence of that disease has declined.

Talaro−Talaro: Foundations

in Microbiology, Fourth

Edition

16. Immunization and

Immune Assays

Text

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2002

478

CHAPTER 16 Immunization and Immune Assays

a primary and secondary anamnestic response (see figure 15.18)

that primes the immune system for future exposure to a virulent

pathogen. If this pathogen enters the body, the immune response

will be immediate, powerful, and sustained.

Vaccines have profoundly reduced the prevalence and impact

of many infectious diseases that were once common and often

deadly. In this section, we survey the principles of vaccine prepara-

tion and important considerations surrounding vaccine indication

and safety. (Vaccines are also given specific consideration in later

chapters on bacterial and viral diseases.)

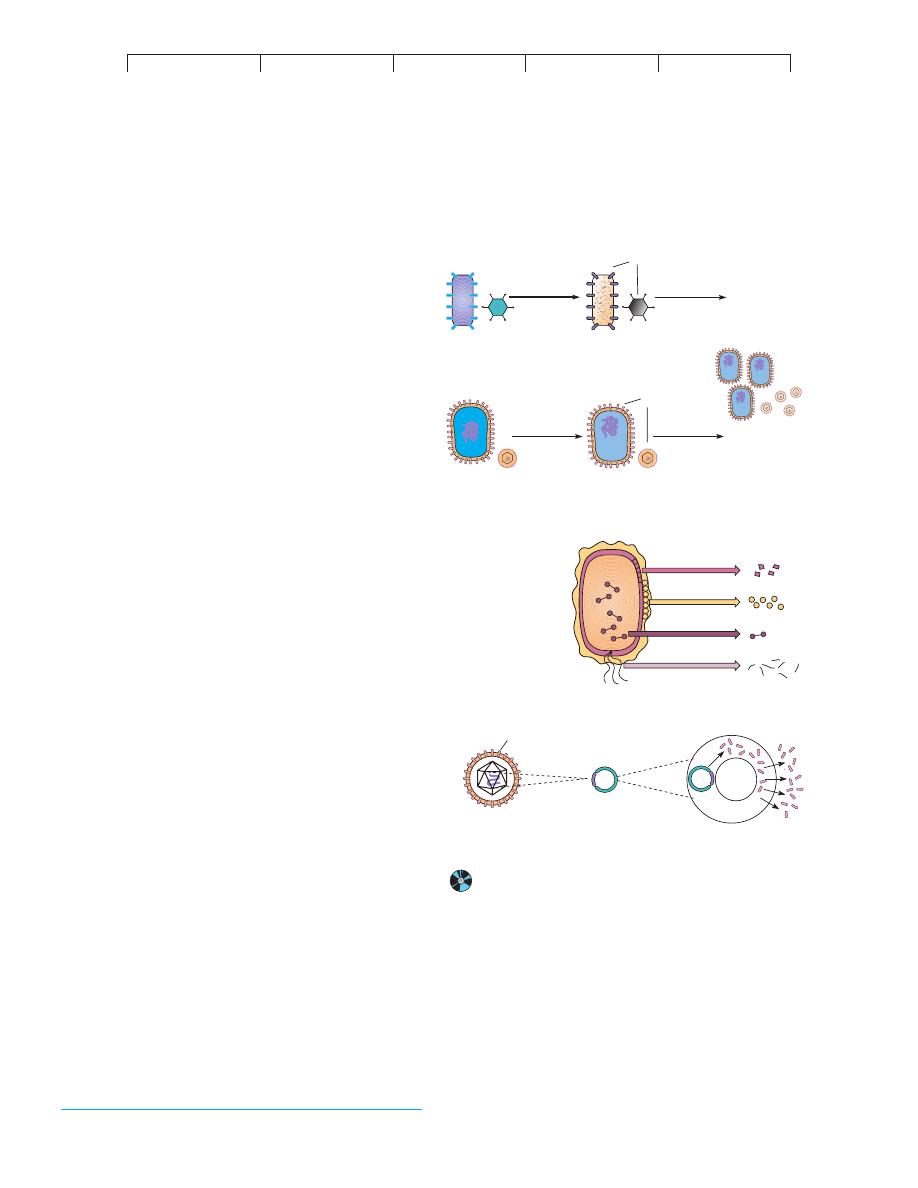

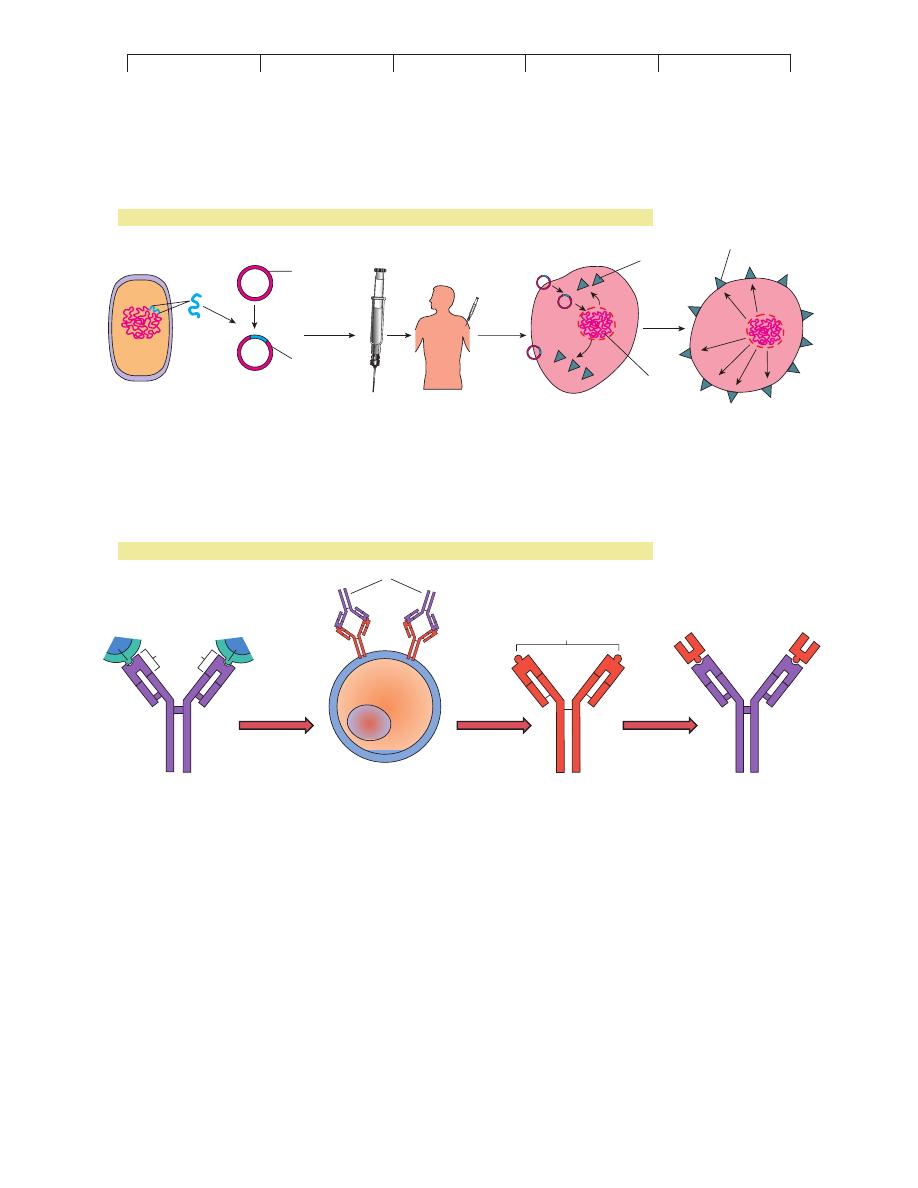

Principles of Vaccine Preparation

A vaccine must be con-

sidered from the standpoints of antigen selection, effectiveness,

ease in administration, safety, and cost. In natural immunity, an

infectious agent stimulates appropriate B and T lymphocytes and

creates memory clones. In artificial active immunity, the objec-

tive is to obtain this same response with a modified version of the

microbe or its components. A safe and effective vaccine should

mimic the natural protective response, not cause a serious infec-

tion or other disease, have long-lasting effects in a few doses,

and be easy to administer. Most vaccine preparations contain one

of the following antigenic stimulants (figure 16.1): (1) killed

whole cells or inactivated viruses, (2) live, attenuated cells or

viruses, (3) antigenic components of cells or viruses, or (4) ge-

netically engineered microbes or microbial antigens. A survey of

the major licensed vaccines and their indications is presented in

table 16.1.

Large, complex antigens such as whole cells or viruses are

very effective immunogens. Depending on the vaccine, these are

either killed or attenuated.

Killed or inactivated vaccines are

prepared by cultivating the desired strain or strains of a bac-

terium or virus and treating them with formalin, radiation, heat,

or some other agent that does not destroy antigenicity. One type

of vaccine for the bacterial disease typhoid fever is of this type

(see chapter 20). Salk polio vaccine and influenza vaccine con-

tain inactivated viruses. Because the microbe does not multiply,

killed vaccines often require a larger dose and more boosters to

be effective.

A number of vaccines are prepared from

live, attenuated*

microbes.

Attenuation is any process that substantially lessens or

negates the virulence of viruses or bacteria. It is usually achieved

by modifying the growth conditions or manipulating microbial

genes in a way that eliminates virulence factors. Attenuation meth-

ods include long-term cultivation, selection of mutant strains that

grow at colder temperatures (cold mutants), passage of the microbe

through unnatural hosts or tissue culture, and removal of virulence

genes. The vaccine for tuberculosis (BCG) was obtained after 13

years of subculturing the agent of bovine tuberculosis (see chapter

19). Vaccines for measles, mumps, polio (Sabin), and rubella con-

tain live, nonvirulent viruses. The advantages that favor live prepa-

rations are: (1) Viable microorganisms can multiply and produce

infection (but not disease) like the natural organism; (2) they confer

long-lasting protection; and (3) they usually require fewer doses

and boosters than other types of vaccines. Disadvantages of using

live microbes in vaccines are that they require special storage facil-

ities, can be transmitted to other people, and can mutate back to a

virulent strain (see polio, chapter 25).

If the exact antigenic determinants that stimulate immunity

are known, it is possible to produce a vaccine based on a selected

component of a microorganism. These vaccines for bacteria are

called

acellular or subcellular vaccines. For viruses, they are

(a) Whole-Cell Vaccines

Killed cell or

inactivated

virus

Dead, but

antigenicity

is retained

Heat or

chemicals

Vaccine

stimulates

immunity

but pathogen

cannot multiply.

Administer

Live, attenuated

cells or viruses

Alive, with

same antigenicity

Virulence

is eliminated

or reduced

Administer

Vaccine

can multiply and

boost immune

stimulation.

Ags

Ags

(b) Acellular or Subunit Vaccine

(c) Recombinant Vaccine

Hepatitis B virus

Surface Ag

Plasmid with gene

that codes for

surface Ag

Yeast cloning vector

Synthesis and release

of surface antigen

FIGURE 16.1

Strategies in vaccine design.

(a) Whole cells or viruses, killed

or attenuated. (b) Acellular or subunit vaccines are made by

disrupting the microbe to release various molecules or cell parts that

can be isolated and purified. (c) Recombinant vaccines are made by

isolating a gene for antigenicity from the pathogen (here a hepatitis

virus) and splicing it into a plasmid. Insertion of the recombinant

plasmid into a cloning host (yeast) results in the production of large

amounts of viral surface antigen to use in vaccine preparation.

*

attenuated

(ah-ten´-yoo-ayt-ed) L.

attenuare, to thin. Able to multiply, but nonvirulent.

Talaro−Talaro: Foundations

in Microbiology, Fourth

Edition

16. Immunization and

Immune Assays

Text

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2002

Practical Applications of Immunologic Function

479

called

subunit vaccines. The antigen used in these vaccines may be

taken from cultures of the microbes, produced by rDNA technol-

ogy, or synthesized chemically.

Examples of component antigens currently in use are the

capsules of the pneumococcus and meningococcus, the protein

surface antigen of anthrax, and the surface proteins of hepatitis B

virus. A special type of vaccine is the

toxoid,* which consists of a

purified bacterial exotoxin that has been chemically denatured. By

eliciting the production of antitoxins that can neutralize the natural

toxin, toxoid vaccines provide protection against toxinoses such as

diphtheria and tetanus.

New Vaccine Strategies

Despite considerable successes, dozens of bacterial, viral, proto-

zoan, and fungal diseases still remain without a functional vaccine.

Of all of the challenges facing vaccine specialists, probably the

most difficult has been choosing a vaccine antigen that is safe and

that properly stimulates immunity. Currently, much attention is

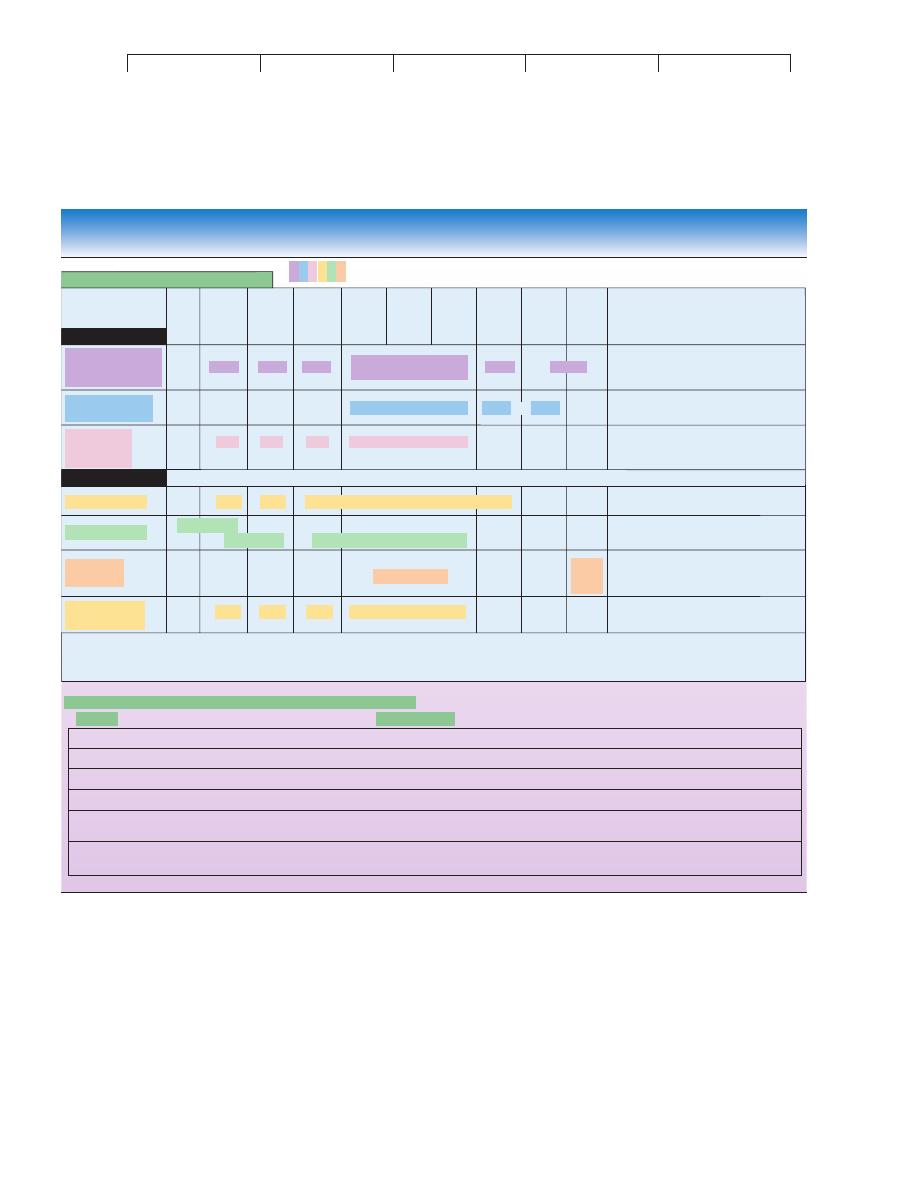

TABLE 16.1

Currently Approved Vaccines

Disease/Preparation

Route of Administration

Recommended Usage/Comments

Contain Killed Whole Bacteria

Cholera

Subcutaneous (SQ) injection

For travelers; effect not long-term

Typhoid

Intramuscular (IM)

For travelers only; efficacy variable

Plague

SQ

For exposed individuals and animal workers; variable protection

Contain Live, Attenuated Bacteria

Tuberculosis (BCG)

Intradermal (ID) injection

For high-risk occupations only; protection variable

Acellular Vaccines (Capsular Polysaccharides)

Meningitis (meningococcal)

SQ

For protection in high-risk infants, military recruits; short duration

Meningitis (

Haemophilus influenzae) IM

For infants and children; may be administered with DTaP

Pneumococcal pneumonia

IM or SQ

Important for people at high risk: the young, elderly, and

immunocompromised; moderate protection

Pertussis (aP)

IM

For newborns and children; contains recombinant protein antigens

Toxoids (Formaldehyde-Inactivated Bacterial Exotoxins)

Diphtheria

IM

A routine childhood vaccination; highly effective in systemic protection

Tetanus

IM

A routine childhood vaccination; highly effective

Botulism

IM

Only for exposed individuals such as laboratory personnel

Contain Inactivated Whole Viruses

Poliomyelitis (Salk)

IM

Routine childhood vaccine; now used as first choice

Rabies

IM

For victims of animal bites or otherwise exposed; effective

Influenza

IM

For high-risk populations; requires constant updating for new strains;

immunity not durable

Hepatitis A

IM

Protection for travelers, institutionalized people

Contain Live, Attenuated Viruses

Adenovirus infection

Oral

For immunizing military recruits

Measles (rubeola)

SQ

Routine childhood vaccine; very effective

Mumps (parotitis)

SQ

Routine childhood vaccine; very effective

Poliomyelitis

Oral

Routine childhood vaccine; very effective, but can cause polio

Rubella

SQ

Routine childhood vaccine; very effective

Chickenpox (varicella)

SQ

Routine childhood vaccine; immunity can diminish over time

Yellow fever

SQ

Travelers, military personnel in endemic areas

Subunit Viral Vaccines

Hepatitis B

IM

Recommended for all children, starting at birth; also for health workers

and others at risk

Influenza

IM

See influenza above

Recombinant Vaccines

Hepatitis B

IM

Used more often than subunit, but for same groups

Pertussis

IM

See acellular above

Lyme Disease (LymeRIX)

IM

Made from the surface protein; used for persons with increased risk of

exposure to ticks

*

toxoid

(tawks´-oyd) Toxinlike.

Talaro−Talaro: Foundations

in Microbiology, Fourth

Edition

16. Immunization and

Immune Assays

Text

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2002

480

CHAPTER 16 Immunization and Immune Assays

being focused on newer strategies for vaccine preparation that

employ antigen synthesis, recombinant DNA, and gene cloning

technology.

When the exact composition of an antigenic determinant is

known, it is possible to synthesize it. This ability permits preserva-

tion of antigenicity while greatly increasing antigen purity and con-

centration. The malaria vaccine currently being used in areas of

South America and Africa is composed of three synthetic peptides

from the parasite. Several biotechnology companies are exploring

the possibility of using plants to synthesize microbial proteins, po-

tentially leading to mass production of edible vaccine antigens.

Some of the genetic engineering concepts introduced in

chapter 10 offer novel approaches to vaccine development. These

methods are particularly effective in designing vaccines for obli-

gate parasites that are difficult or expensive to culture, such as the

syphilis spirochete or the malaria parasite. This technology pro-

vides a means of isolating the genes that encode various microbial

antigens, inserting them into plasmid vectors, and cloning them in

appropriate hosts. The outcome of recombination can be varied as

desired. For instance, the cloning host can be stimulated to synthe-

size and secrete a protein product (antigen), which is then harvested

and purified (figure 16.1

c). This is how certain vaccines for hepati-

tis B rotavirus and Lyme disease are prepared. Antigens from the

agents of syphilis,

Schistosoma, and influenza have been similarly

isolated and cloned and are currently being considered as potential

vaccine material.

Another ingenious technique using genetic recombination

has been nicknamed the

Trojan horse vaccine. The term derives

from an ancient legend in which the Greeks sneaked soldiers into

the fortress of their Trojan enemies by hiding them inside a large,

mobile wooden horse. In the microbial equivalent, genetic material

from a selected infectious agent is inserted into a live carrier

microbe that is nonpathogenic. In theory, the recombinant microbe

will multiply and express the foreign genes, and the vaccine

recipient will be immunized against the microbial antigens.

Vaccinia, the virus originally used to vaccinate for smallpox, and

adenoviruses have proved practical agents for this technique.

Vaccinia is used as the carrier in one of the experimental vaccines

for AIDS (see figure 25.19), herpes simplex 2, leprosy, and tuber-

culosis.

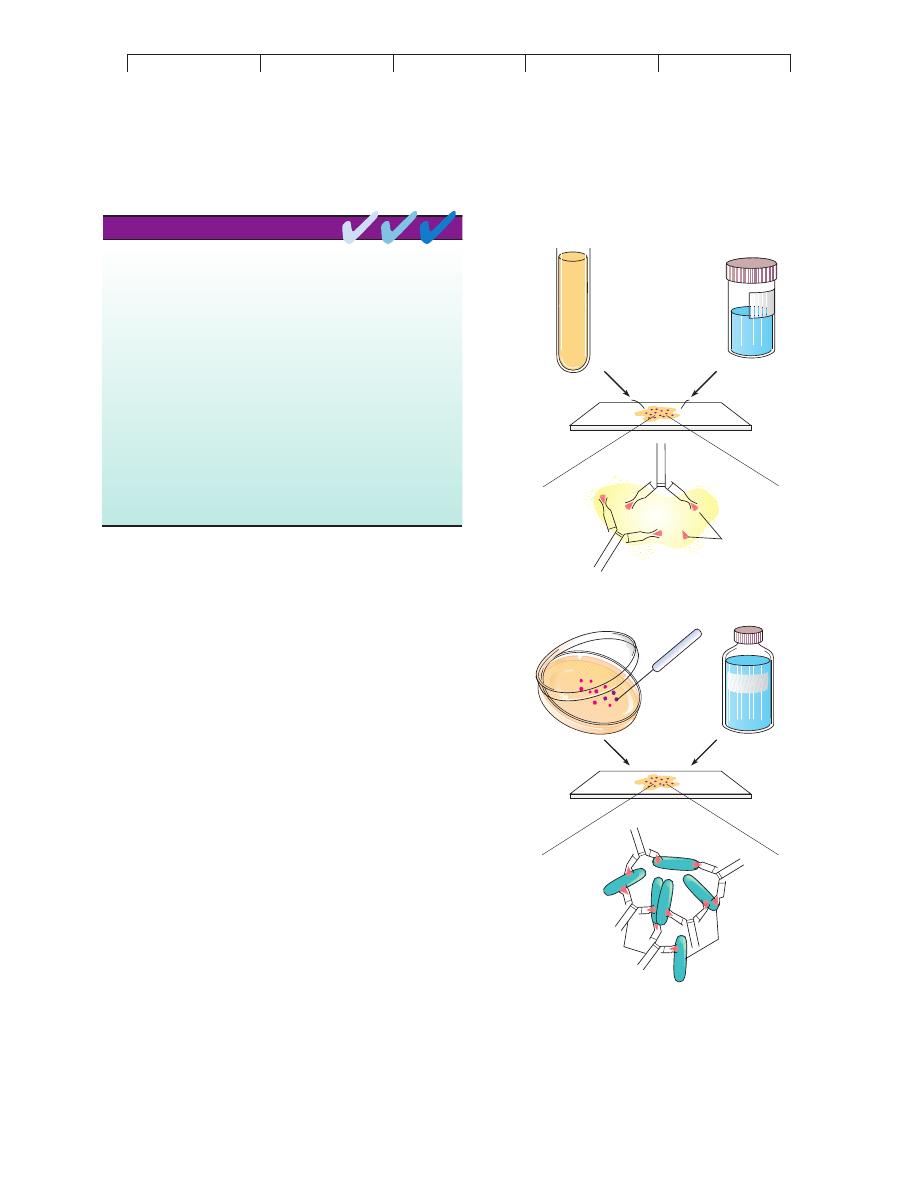

DNA vaccines are being hailed as the most promising of all

of the newer approaches to immunization. The technique in these

formulations is very similar to gene therapy as described in figure

10.13, except in this case, microbial (not human) DNA is inserted

into a plasmid vector and inoculated into a recipient (figure 16.2

a).

The expectation is that the human cells will take up some of the

plasmids and express the microbial DNA in the form of proteins.

Because these proteins are foreign, they will be recognized during

immune surveillance and cause B and T cells to be sensitized and

form memory cells.

Experiments with animals have shown that these vaccines

are very safe and that only a small amount of the foreign antigen

need be expressed to produce effective immunity. Another advan-

tage to this method is that any number of potential microbial pro-

teins can be expressed, making the antigenic stimulus more com-

plex and improving the likelihood that it will stimulate both

antibody and cell-mediated immunity. At the present time, over

30 DNA-based vaccines are being tested in animals. Vaccines for

Lyme disease, hepatitis C, herpes simplex, influenza, tuberculosis,

papillomavirus, and malaria are undergoing animal trials, most

with encouraging results.

Vaccine effectiveness relies, in part, on the production of

antibodies that closely fit the natural antigen. Realizing that such

reactions are very much like a molecular jigsaw puzzle, researchers

have proposed an entirely new concept in vaccines. The

anti-

idiotype vaccine is based on the principle that the antigen binding

(variable) region, or

idiotype,* of a given antibody (A) can be

antigenic to a genetically different recipient and can cause that

recipient’s immune system to produce antibodies (B; also called

anti-idiotypic antibodies) specific for the variable region on anti-

body A (figure 16.2

b). The purpose for making anti-idiotypic

antibodies is that they will display an identical configuration as the

desired antigen and can be used in vaccines. This method avoids

administering a microbial antigen, thus reducing the potential for

dangerous side effects. Using monoclonal antibodies, this approach

has been used to mimic the surface antigen of hepatitis B virus and

Trypanosoma with some success.

Route of Administration and Side Effects

of Vaccines

Most vaccines are injected by subcutaneous, intramuscular, or intra-

dermal routes. Oral vaccines are available for only two diseases

(table 16.1), but they have some distinct advantages. An oral dose

of a vaccine can stimulate protection (IgA) on the mucous mem-

brane of the portal of entry. Oral vaccines are also easier to give,

more readily accepted, and well tolerated. Some vaccines require

the addition of a special binding substance, or

adjuvant.* An

adjuvant is any compound that enhances immunogenicity and

prolongs antigen retention at the injection site. The adjuvant pre-

cipitates the antigen and holds it in the tissues so that it will be

released gradually. Its gradual release, presumably, facilitates con-

tact with macrophages and lymphocytes. Common adjuvants are

alum (aluminum hydroxide salts), Freund’s adjuvant (emulsion of

mineral oil, water, and extracts of mycobacteria), and beeswax.

Vaccines must go through many years of trials in experimen-

tal animals and humans before they are licensed for general use.

Even after they have been approved, like all therapeutic products,

they are not without complications. The most common of these are

local reactions at the injection site, fever, allergies, and other

adverse reactions. Relatively rare reactions (about 1 case out of

220,000 vaccinations) are panencephalitis (from measles vaccine),

back-mutation to a virulent strain (from polio vaccine), disease due

to contamination with dangerous viruses or chemicals, and neuro-

logical effects of unknown cause (from pertussis and swine flu vac-

cines). Some patients experience allergic reactions to the medium

(eggs or tissue culture) rather than to vaccine antigens. Some recent

studies have attempted to link childhood vaccinations to later

development of diabetes, asthma, and autism. After thorough

examination of records, epidemiologists have found no convincing

evidence for a connection to these diseases.

*

idiotype

(id´-ee-oh-type) Gr.

idios, own, peculiar. Another term for the antigen binding

site.

*

adjuvant

(ad´-joo-vunt) L.

adjuvare, to help.

Talaro−Talaro: Foundations

in Microbiology, Fourth

Edition

16. Immunization and

Immune Assays

Text

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2002

Practical Applications of Immunologic Function

481

When known or suspected adverse effects have been de-

tected, vaccines are altered or withdrawn. Most recently, the

whole-cell pertussis vaccine was replaced by the acellular capsule

(aP) form when it was associated with adverse neurological ef-

fects. The live oral rotavirus vaccine had to be withdrawn when

children experienced intestinal blockage. Polio vaccine was

switched from live, oral to inactivated when too many cases of

paralytic disease occurred from back-mutated vaccine stocks. Vac-

cine companies are also phasing out certain preservatives

(thimerosal) that are thought to cause allergies and other potential

side effects.

Professionals involved in giving vaccinations must under-

stand their inherent risks but also realize that the risks from the

infectious disease almost always outweigh the chance of an adverse

vaccine reaction. The greatest caution must be exercised in giving

live vaccines to immunocompromised or pregnant patients, the lat-

ter because of possible risk to the fetus.

To Vaccinate: Why, Whom, and When?

Vaccination confers long-lasting, sometimes lifetime, protection

in the individual, but an equally important effect is to protect the

public health. Vaccination is an effective method of establishing

Protein

from

pathogen

Protein expresed

on surface of cell

Nucleus

Foreign protein

of pathogen is

inserted into

cell membrane,

where it will

stimulate immune

response.

Cells of subject

accept plasmid

with pathogen's

DNA. DNA is

transcribed and

translated into

various proteins.

DNA vaccine

injected into

subject.

Rabbit Ab

(b) Technology for anti-idiotypic vaccines

Mouse B-cell clone

recognizes foreign

idiotype.

Idiotype

of Ab

Rabbit Ab (antibody A)

Anti-idiotypic Ab

(antibody B)

produced.

New antibodies with

same specificity for Ag

as original Ab A.

Injected into

human as

vaccine Ag

Ab alone

injected

into mouse

Anti-idiotype has

same configuration

as Ag in (1)

Genomic DNA

inserted into

plasmid vector;

plasmid is

amplified and

prepared as

vaccine.

DNA that codes

for protein antigen

extracted from

pathogen genome.

DNA of

pathogen

Plasmid

Plasmid

with DNA

(2)

(1)

(3)

(4)

(3)

(2)

(1)

(4)

(5)

Ag

Ag

(a) Technology for DNA vaccines

FIGURE 16.2

Other technologies useful in preparing vaccines.

(a) DNA vaccines contain all or part of the pathogen’s DNA, which is used to “infect” recipient’s

cells. Processing of the DNA leads to production of an antigen protein that can stimulate a specific response against that pathogen. (b) Anti-idiotypic

vaccines use antibodies as foreign proteins to mimic the structure of the natural antigen. See text for details.

Talaro−Talaro: Foundations

in Microbiology, Fourth

Edition

16. Immunization and

Immune Assays

Text

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2002

482

CHAPTER 16 Immunization and Immune Assays

herd immunity in the population. According to this concept, in-

dividuals immune to a communicable infectious disease will not

be carriers, and therefore the occurrence of that microbe will be

reduced. With a larger number of immune individuals in a popu-

lation (herd), it will be less likely that an unimmunized member

of the population will encounter the agent. In effect, collective

immunity through mass immunization confers indirect protec-

tion on the nonimmune (such as children). Herd immunity main-

tained through immunization is an important force in averting

epidemics.

Vaccination is recommended for all typical childhood dis-

eases for which a vaccine is available and for people in certain

special circumstances (health workers, travelers, military person-

nel). Table 16.2 outlines a general schedule for childhood immu-

nization and the indication for special vaccines. Not only are some

vaccines mixtures of antigens, but in certain cases several vaccines

are also administered simultaneously. Examples are military recr-

uits who receive as many as 15 injections within a few minutes and

children who receive boosters for DTaP and polio at the same time

they receive the MMR vaccine. Experts doubt that immune inter-

ference (inhibition of one immune response by another) is a signif-

icant problem in these instances, and the mixed vaccines are care-

fully balanced to prevent this eventuality. The main problem with

simultaneous administration is that side effects can be amplified.

TABLE 16.2

Recommended Regimen and Indications for Routine Vaccinations

Routine Schedules for Children and Adults

Vaccine

Birth

2

Months

4

Months

6

Months

12

Months

15

Months

18

Months

4–6

Years

11–12

Years

Adults Comments

Mixed vaccines

Td is tetanus/diphtheria; T is tetanus

alone; either one should be given as

booster every 10 years.

First dose varies with disease incidence;

booster given at either 4– 6 or 11–12 years.

Schedule depends upon source of

vaccine; given with DTaP as TriHIBit

Single vaccines

Similar schedule to DTaP; injected

vaccine

Option depends upon condition of

infant; 3 doses given

Cannot be given to children <1 year old

or

Diphtheria,

Tetanus,

Pertussis

1

(DTaP)

DTaP

one dose

Td or T

Measles,

2

Mumps,

Rubella (MMR)

MMR

MMR

MMR

Haemophilus

influenzae

type b (Hib)

Hib

Hib

Hib

Hib

IPV

IPV

Hepatitis B (HB)

HB option 1

HB option 2

HB option 3

Chickenpox

(CPV)

CPV one dose

CPV

two

doses

Shaded bars indicate that a dose can be

given once during this time frame

2

Measles vaccine (Attenuvax) can be given alone

to children during epidemics or to adults immunized

before 1970.

Used in Cases of Specific Risk Due to Occupational or Other Exposure

Group Targeted

Health care personnel; people exposed through life-style

Children 2–14 years who live in areas of high prevalence

Elderly patients, children with sickle-cell anemia

Hospital, laboratory, health care workers

People whose jobs involve contact with animals (veterinarians, forest rangers); known or

suspected exposure to rabid animal; living in areas of high incidence

Travelers to endemic regions, including military recruits (varies with geographic destination)

Vaccine

Hepatitis B (Recombivax)

Hepatitis A (Havrix)

Pneumococcus (Pneumovax)

Influenza, polio, tuberculosis (BCG)

Rabies, plague, Lyme disease

Cholera, hepatitis B, hepatitis A, measles, yellow fever,

meningococcal meningitis, polio, rabies, typhoid, plague

Pneumococcus

Vaccine (PV)

PV

PV

PV

PV

DTaP

DTaP

DTaP

DTaP

Used to protect children against otitis

media

Poliovirus (IPV)

3

IPV

one dose

IPV

1

DTaP. The diphtheria–tetanus–acellular pertussis

vaccine has replaced the DTP.

3

IPV—inactivated polio vaccine—is now indicated

as a safer alternative to the oral polio vaccine.

Talaro−Talaro: Foundations

in Microbiology, Fourth

Edition

16. Immunization and

Immune Assays

Text

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2002

Practical Applications of Immunologic Function

483

SEROLOGICAL AND IMMUNE TESTS: MEASURING

THE IMMUNE RESPONSE IN VITRO

The antibodies formed during an immune reaction are important in

combating infection, but they hold additional practical value. Char-

acteristics of antibodies (such as their quantity or specificity) can

reveal the history of a patient’s contact with microorganisms or

other antigens. This is the underlying basis of

serological testing.

Serology is the branch of immunology that traditionally deals with

in vitro diagnostic testing of serum. Serological testing is based on

the familiar concept that antibodies have extreme specificity for

antigens, so when a particular antigen is exposed to its specific an-

tibody, it will fit like a hand in a glove. The ability to visualize this

interaction by some means provides a powerful tool for detecting,

identifying, and quantifying antibodies—or for that matter, anti-

gens. The scheme works both ways, depending on the situation.

One can detect or identify an unknown antibody using a known

antigen, or one can use an antibody of known specificity to help de-

tect or identify an unknown antigen (figure 16.3). Modern serolog-

ical testing has grown into a field that tests more than just serum.

Urine, cerebrospinal fluid, whole tissues, and saliva can also be

used to determine the immunologic status of patients. These and

other immune tests are helpful in confirming a suspected diagnosis

or in screening a certain population for disease.

General Features of Immune Testing

The strategies of immunologic tests are diverse, and they underline

some of the brilliant and imaginative ways that antibodies and anti-

gens can be used as tools. We will summarize them under the head-

ings of agglutination, precipitation, immunodiffusion, complement

fixation, fluorescent antibody tests, and immunoassay tests. First

we will overview the general characteristics of immune testing, and

we will then look at each type separately.

The most effective serological tests have a high degree of

specificity and sensitivity (figure 16.4).

Specificity is the property

of a test to focus upon only a certain antibody or antigen and not to

Knowledge of the specific immune response has two practical

applications: (1) commercial production of antisera and vaccines and

(2) development of rapid, sensitive methods of disease diagnosis.

Artificial passive immunity usually involves administration of antiserum,

and occasionally B and T cells. Antibodies collected from donors

(human or otherwise) are injected into people who need protection

immediately. Examples include ISG (immune serum globulin) and SIG

(specific immune globulin).

Artificial active agents are vaccines that provoke a protective immune

response in the recipient but do not cause the actual disease.

Vaccination is the process of challenging the immune system with a

specially selected antigen. Examples are (1) killed or inactivated

microbes, (2) live, attenuated microbes, (3) subunits of microbes, and

(4) genetically engineered microbes or microbial parts.

Vaccination programs seek to protect the individual directly through

raising the antibody titer and indirectly through the development of

herd immunity.

CHAPTER CHECKPOINTS

Patient's serum

antibody content unknown

Macroscopic

reaction

Prepared

known

antigen

Isolated colony,

identity unknown

ANTISERUM

Macroscopic

reaction

Ag

Antibodies of

known

identity

Ab

Ag

(a)

(b)

FIGURE 16.3

Basic principles of testing using antibodies and antigens.

(a) In

serological diagnosis of disease, a blood sample is scanned for the

presence of antibody using an antigen of known specificity. A positive

reaction is usually evident as some visible sign, such as color change

or clumping, that indicates a specific interaction between antibody and

antigen. (The reaction at the molecular level is rarely observed.) (b) An

unknown microbe is mixed with serum containing antibodies of known

specificity, a procedure known as serotyping. Microscopically or

macroscopically observable reactions indicate a correct match between

antibody and antigen and permit identification of the microbe.