Talaro−Talaro: Foundations

in Microbiology, Fourth

Edition

17. Disorders in Immunity

Text

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2002

497

umans possess a powerful and intricate system of defense,

which by its very nature also carries the potential to cause

injury and disease. In most instances, a defect in immune

function is expressed in commonplace, but miserable, symptoms such

as those of hay fever and dermatitis. But abnormal or undesirable

immune functions are also actively involved in debilitating or life-

threatening diseases such as asthma, anaphylaxis, rheumatoid arthri-

tis, graft rejection, and cancer.

Chapter Overview

• The immune system is subject to several types of dysfunctions termed

immunopathologies.

• Some dysfunctions are due to abnormally heightened responses to

antigens as manifested in allergies, hypersensitivities, and

autoimmunities.

• Some dysfunctions are due to the reduction or loss in protective immune

reactions due to genetic or environmental causes, as exemplified by

immunodeficiencies and cancer.

• Some immune damage is caused by normal actions that are directed at

foreign tissues placed in the body for therapy, such as transfusions and

transplants.

• Hypersensitivities are divided into immediate, antibody-mediated,

immune complex, and delayed allergies.

• Allergens are the foreign molecules from the environment, other

organisms, or even from the body that cause a hypersensitive or allergic

response.

• Most hypersensitivities require an initial sensitizing event, followed by a

later contact that causes symptoms.

• The immediate type of allergy is mediated by special types of B cells

that produce an antibody called IgE. IgE can cause mast cells to

release allergic chemicals such as histamine that stimulate symptoms.

• Examples of immediate allergies are atopy, asthma, food allergies, and

anaphylaxis.

• Another type of hypersensitivity arises from the action of other

antibodies (IgG and IgM) that can fix complement and lyse foreign

cells. An example is the reaction due to incompatible blood transfusions

or placental transfer.

• Immune complex reactions are caused by large amounts of circulating

antibodies against foreign molecules accumulating in tissues and

organs.

• Autoimmune diseases are due to the production of B and T cells that

are abnormally sensitized to react with the body’s natural molecules and

H

thus can damage cells and tissues. Some examples of these diseases

include rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, myasthenia

gravis, and multiple sclerosis.

• T cells are involved in delayed-type hypersensitivities wherein allergens

cause damage to cells and graft rejection.

• Immunodeficiencies are pathologies in which B and T cells and other

immune cells are missing or destroyed. They may be inborn and

genetic or acquired.

• The primary outcome of immunodeficiencies is manifest in recurrent

infections and lack of immune competence.

• Cancer is an abnormal overgrowth of cells due to a genetic defect and

the lack of effective immune surveillance.

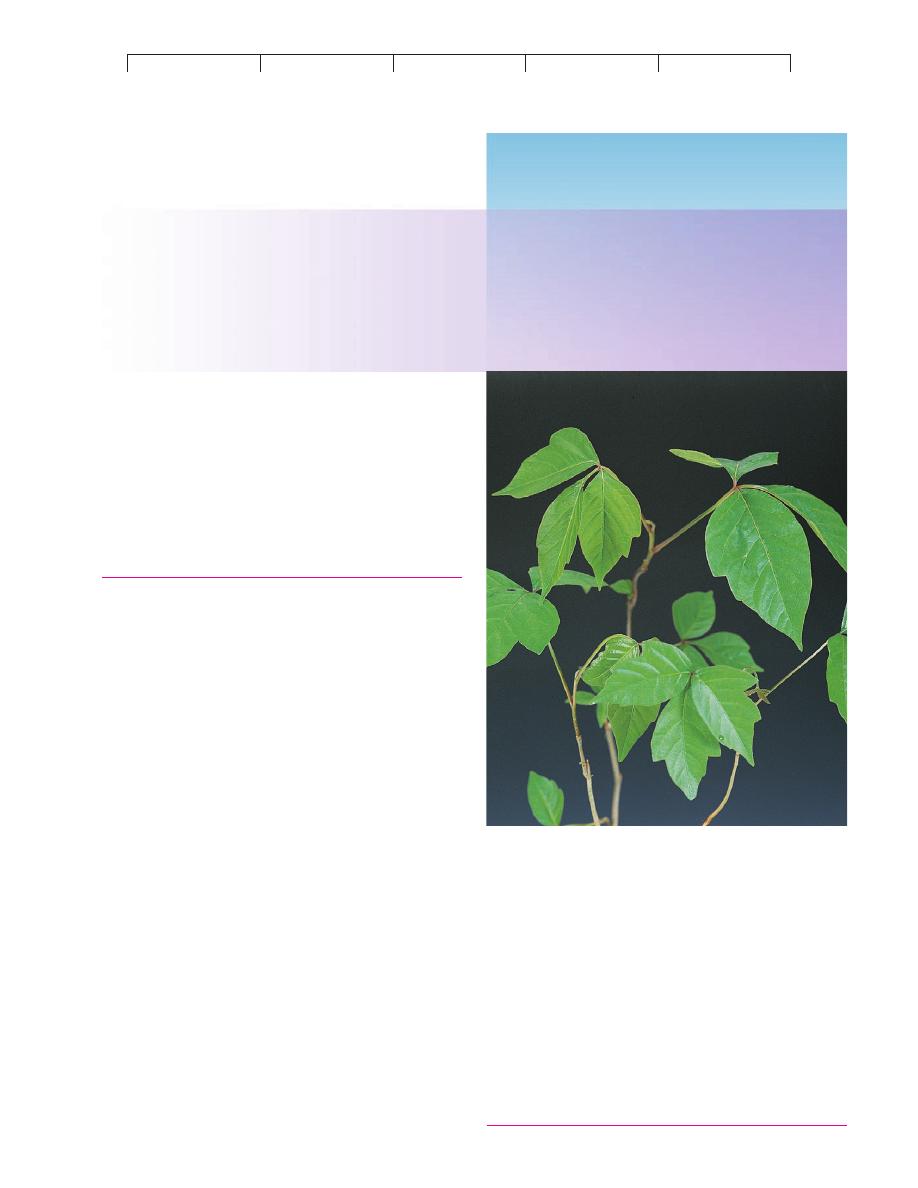

This delicate poison ivy plant, along with its close relatives poison oak and

sumac, is one of the most common causes of allergy in the United States.

Its leaves contain an oil that many people are sensitive to. The nature of its

effects are covered in this chapter.

CHAPTER

17

Disorders in Immunity

Talaro−Talaro: Foundations

in Microbiology, Fourth

Edition

17. Disorders in Immunity

Text

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2002

498

CHAPTER 17 Disorders in Immunity

The Immune Response:

A Two-Sided Coin

With few exceptions, our previous discussions of the immune re-

sponse have centered around its numerous beneficial effects. The

precisely coordinated system that seeks out, recognizes, and de-

stroys an unending array of foreign materials is clearly protective,

but it also presents another side—a side that promotes rather than

prevents disease. In this chapter, we will survey

immunopathol-

ogy, the study of disease states associated with overreactivity or un-

derreactivity of the immune response (figure 17.1). In the cases of

allergies and autoimmunity, the tissues are innocent bystanders

attacked by excessive immunologic functions. In

grafts and trans-

fusions, a recipient reacts to the foreign tissues and cells of another

individual. In

immunodeficiency diseases, immune function is in-

completely developed, suppressed, or destroyed.

Cancer falls into

a special category, because it is both a cause and an effect of im-

mune dysfunction. As we shall see, one fascinating by-product of

studies of immune disorders has been our increased understanding

of the basic workings of the immune system.

Overreactions to Antigens:

Allergy/Hypersensitivity

The term

allergy* means a condition of altered reactivity or

exaggerated immune response that is manifested by inflammation.

Although it is sometimes used interchangeably with

hypersensitiv-

ity, some experts refer to immediate reactions such as hay fever as

allergies and to delayed reactions as hypersensitivities. Allergic

individuals are acutely sensitive to repeated contact with antigens,

called

allergens, that do not noticeably affect nonallergic individu-

als. Although the general effects of hyperactivity are detrimental,

we must be aware that it involves the very same types of immune

reactions as those at work in protective immunities. These include

humoral and cell-mediated actions, the inflammatory response,

phagocytosis, and complement. Such an association means that all

humans have the potential to develop hypersensitivity under

particular circumstances.

Immunodeficiency

T

B

U

n

de

rre

actio

n

Over

rea

ct

io

n

B

T

Cancer

A

n

tig

enic

Stimu

la

tio

n

L

o

ss

of

Im

m

unity

Hyper

sen

sit

iv

iti

es

Type I.

Immediate

(hay fever,

anaphylaxis)

Type II.

Antibody-mediated (blood type

incompatibilities)

Type III.

Immune complex

(rheumatoid arthritis, serum

sickness)

Type IV.

Cell-mediated, cytotoxic

(contact dermatitis, graft rejection)

*

allergy

(al

-er-jee) Gr. allos, other, and ergon, work.

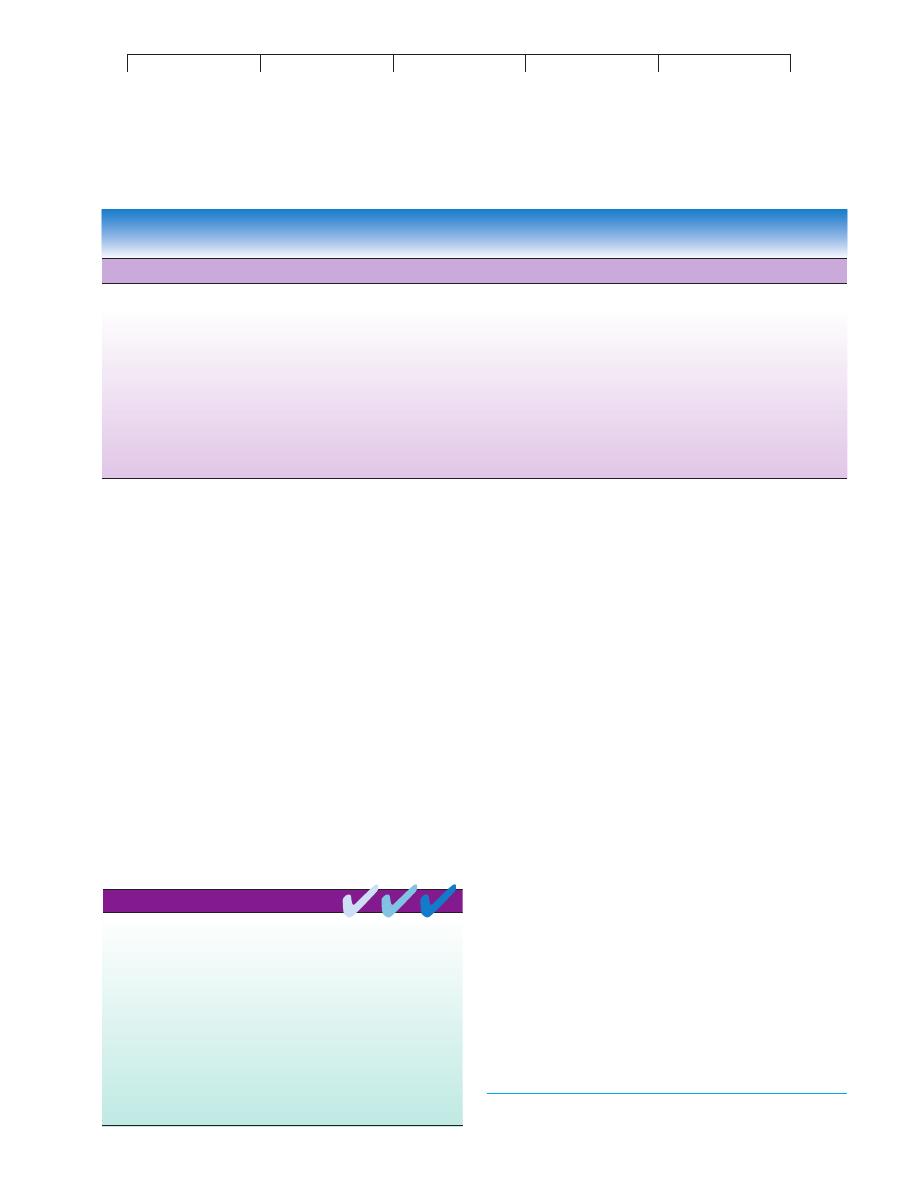

FIGURE 17.1

Overview of diseases of the immune system.

Just as the system of T cells and B cells provides necessary protection against infection and

disease, the same system can cause serious and debilitating conditions by overreacting or underreacting to immune stimuli.

Talaro−Talaro: Foundations

in Microbiology, Fourth

Edition

17. Disorders in Immunity

Text

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2002

Type I Allergic Reactions: Atopy and Anaphylaxis

499

Originally, allergies were defined as either immediate or

delayed, depending upon the time lapse between contact with the

allergen and onset of symptoms. Subsequently, they were differ-

entiated as humoral versus cell-mediated. But as information on

the nature of the allergic immune response accumulated, it be-

came evident that, although useful, these schemes oversimplified

what is really a very complex spectrum of reactions. The most

widely accepted classification, first introduced by immunologists

P. Gell and R. Coombs, includes four major categories: type I

(atopy and anaphylaxis), type II (IgG- and IgM-mediated cell

damage), type III (immune complex), and type IV (delayed hyper-

sensitivity) (table 17.1). In general, types I, II, and III involve a

B-cell–immunoglobulin response, and type IV involves a T-cell re-

sponse (figure 17.1). The antigens that elicit these reactions can be

exogenous, originating from outside the body (microbes, pollen

grains, and foreign cells and proteins), or endogenous, arising from

self tissue (autoimmunities).

One of the reasons allergies are easily mistaken for infections

is that both involve damage to the tissues and thus trigger the

inflammatory response (see figure 14.18). Many symptoms and

signs of inflammation (redness, heat, skin eruptions, edema, and

granuloma) are prominent features of allergies.

Type I Allergic Reactions:

Atopy and Anaphylaxis

All type I allergies share a similar physiological mechanism, are

immediate in onset, and are associated with exposure to specific

antigens. However, it is convenient to recognize two subtypes:

Atopy* is any chronic local allergy such as hay fever or asthma;

anaphylaxis* is a systemic, often explosive reaction that involves

airway obstruction and circulatory collapse. In the following sec-

tions, we will consider the epidemiology of type I allergies, aller-

gens and routes of inoculation, mechanisms of disease, and specific

syndromes.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND MODES OF

CONTACT WITH ALLERGENS

Allergies exert profound medical and economic impact. Allergists

(physicians who specialize in treating allergies) estimate that about

10% to 30% of the population is prone to atopic allergy. It is gener-

ally acknowledged that self-treatment with over-the-counter medi-

cines accounts for significant underreporting of cases. The 35 million

people afflicted by hay fever (15–20% of the population) spend

about half a billion dollars annually for medical treatment. The

monetary loss due to employee debilitation and absenteeism is im-

measurable. The majority of type I allergies are relatively mild, but

certain forms such as asthma and anaphylaxis may require hospi-

talization and cause death. About 2 million people in the United

States suffer from asthma.

The predisposition for type I allergies is inherited. Be aware

that what is hereditary is a generalized susceptibility, not the allergy

to a specific substance. For example, a parent who is allergic to rag-

weed pollen can have a child who is allergic to cat hair. The

prospect of a child’s developing atopic allergy is at least 25% if one

parent is atopic, increasing up to 50% if grandparents or siblings

are also afflicted. The actual basis for atopy appears to be a genetic

TABLE 17.1

Hypersensitivity States

Type

Systems and Mechanisms Involved

Examples

I.

Immediate hypersensitivity

IgE-mediated; involves mast cells,

Anaphylaxis, atopic allergies such as hay

basophils, and allergic mediators

fever, asthma

II.

Antibody-mediated

IgG, IgM antibodies act upon cells with

Blood group incompatibility, pernicious

complement and cause cell lysis; includes

anemia; myasthenia gravis

some autoimmune diseases

III.

Immune complex–mediated

Antibody-mediated inflammation; circulating

Systemic lupus erythematosus; rheumatoid

IgG complexes deposited in basement

arthritis; serum sickness; rheumatic fever

membranes of target organs; includes

some autoimmune diseases

IV.

T cell–mediated

Delayed hypersensitivity and cytotoxic

Infection reactions; contact dermatitis; graft

reactions in tissues

rejection; some types of autoimmunity

such as diabetes

Immunopathology is the study of diseases associated with excesses and

deficiencies of the immune response. Such diseases include allergies,

autoimmunity, grafts, transfusions, immunodeficiency disease, and

cancer.

An allergy or hypersensitivity is an exaggerated immune response that

injures or inflames tissues.

There are four categories of hypersensitivity reactions: type I (atopy and

anaphylaxis), type II (transfusion reactions), type III (immune complex

reactions), and type IV (delayed hypersensitivity reactions).

Antigens that trigger hypersensitivity reactions are allergens. They can be

either exogenous (originate outside the host) or endogenous (involve the

host’s own tissue).

CHAPTER CHECKPOINTS

*

atopy

(at

-oh-pee) Gr. atop, out of place.

*

anaphylaxis

(an

-uh-fih-lax-us) Gr. ana, excessive, and phylaxis, protection.

Talaro−Talaro: Foundations

in Microbiology, Fourth

Edition

17. Disorders in Immunity

Text

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2002

500

CHAPTER 17 Disorders in Immunity

program that favors allergic antibody (IgE) production, increased

reactivity of mast cells, and increased susceptibility of target tissue

to allergic mediators. Allergic persons often exhibit a combination

of syndromes, such as hay fever, eczema, and asthma.

Other factors that affect the presence of allergy are age,

infection, and geographic locale. New allergies tend to crop up

throughout an allergic person’s life, especially as new exposures

occur after moving or changing life-style. In some persons, atopic

allergies last for a lifetime; others “outgrow” them, and still others

suddenly develop them later in life. Some features of allergy are not

yet completely explained.

THE NATURE OF ALLERGENS AND

THEIR PORTALS OF ENTRY

As with other antigens, allergens have certain immunogenic char-

acteristics. Not unexpectedly, proteins are more allergenic than

carbohydrates, fats, or nucleic acids. Some allergens are haptens,

non-proteinaceous substances with a molecular weight of less than

1,000 that can form complexes with carrier molecules in the body

(see figure 15.11). Organic and inorganic chemicals found in indus-

trial and household products, cosmetics, food, and drugs are com-

monly of this type. Table 17.2 lists a number of common allergenic

substances.

Allergens typically enter through epithelial portals in the res-

piratory tract, gastrointestinal tract, and skin. The mucosal surfaces

of the gut and respiratory system present a thin, moist surface that

is normally quite penetrable. The dry, tough keratin coating of skin

is less permeable, but access still occurs through tiny breaks,

glands, and hair follicles. It is worth noting that the organ of aller-

gic expression may or may not be the same as the portal of entry.

Airborne environmental allergens such as pollen, house dust,

dander (shed skin scales), or fungal spores are termed inhalants.

Each geographic region harbors a particular combination of air-

borne substances that varies with the season and humidity (figure

17.2a). Pollen, the most common offender, is given off seasonally

by the reproductive structures of pines and flowering plants (weeds,

trees, and grasses). Unlike pollen, mold spores are released

throughout the year and are especially profuse in moist areas of the

home and garden. Airborne animal hair and dander, feathers, and

the saliva of dogs and cats are common sources of allergens. The

component of house dust that appears to account for most dust al-

lergies is not soil or other debris, but the decomposed bodies of tiny

mites that commonly live in this dust (figure 17.2b). Some people

are allergic to their work, in the sense that they are exposed to al-

lergens on the job. Examples include florists, beauty operators,

woodworkers, farmers, drug processors, welders, and plastics man-

ufacturers whose work can aggravate inhalant allergies.

Allergens that enter by mouth, called ingestants, often cause

food allergies: Injectant allergies are an important adverse side

effect of drugs or other substances used in diagnosing, treating, or

preventing disease. A natural source of injectants is venom from

stings by hymenopterans, a family of insects that includes honey-

bees and wasps. Contactants are allergens that enter through the

skin. Many contact allergies are of the type IV, delayed variety

discussed later in this chapter.

MECHANISMS OF TYPE I ALLERGY:

SENSITIZATION AND PROVOCATION

What causes some people to sneeze and wheeze every time they

step out into the spring air, while others suffer no ill effects? In

order to answer this question, we must examine what occurs in the

tissues of the allergic individual that does not occur in the normal

person. In general, type I allergies develop in stages (figure 17.3).

The initial encounter with an allergen provides a

sensitizing dose

that primes the immune system for a subsequent encounter with

that allergen but generally elicits no signs or symptoms. The mem-

ory cells and immunoglobulin are then ready to react with a subse-

quent

provocative dose of the same allergen. It is this dose that

precipitates the signs and symptoms of allergy. Despite numerous

anecdotal reports of people showing an allergy upon first contact

with an allergen, it is generally believed that these individuals un-

knowingly had contact at some previous time. Fetal exposure to

allergens from the mother’s bloodstream is one possibility, and

foods can be a prime source of “hidden” allergens such as penicillin.

The Physiology of IgE-Mediated Allergies

During primary contact and sensitization, the allergen penetrates the

portal of entry (figure 17.3a). When large particles such as pollen

grains, hair, and spores encounter a moist membrane, they release

molecules of allergen that pass into the tissue fluids and lymphatics.

The lymphatics then carry the allergen to the lymph nodes, where

specific clones of B cells recognize it, are activated, and proliferate

into plasma cells. These plasma cells produce

immunoglobulin E

(IgE), the antibody of allergy. IgE is different from other im-

munoglobulins in having an Fc receptor region with great affinity

for mast cells and basophils. The binding of IgE to these cells in the

tissues sets the scene for the reactions that occur upon repeated ex-

posure to the same allergen (see figures 17.3b and 17.6).

The Role of Mast Cells and Basophils

The most important characteristics of mast cells and basophils

relating to their roles in allergy are:

1. Their ubiquitous location in tissues. Mast cells are

located in the connective tissue of virtually all organs, but

particularly high concentrations exist in the lungs, skin,

gastrointestinal tract, and genitourinary tract. Basophils

circulate in the blood but migrate readily into tissues.

TABLE 17.2

Common Allergens, Classified by Portal of Entry

Inhalants

Ingestants

Injectants

Contactants

Pollen

Food

Hymenopteran

Drugs

Dust

(chocolate,

venom (bee,

Cosmetics

Mold spores

wheat, eggs,

wasp)

Heavy metals

Dander

milk, nuts,

Drugs

Detergents

Animal hair

strawberries;

Vaccines

Formalin

Insect parts

fish)

Serum

Rubber

Formalin

Food additives

Enzymes

Glue

Drugs

Drugs (aspirin,

Hormones

Solvents

Enzymes

penicillin)

Dyes

Talaro−Talaro: Foundations

in Microbiology, Fourth

Edition

17. Disorders in Immunity

Text

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2002

Type I Allergic Reactions: Atopy and Anaphylaxis

501

2. Their capacity to bind IgE during sensitization (figure

17.3). Each cell carries 30,000 to 100,000 cell receptors

that attract 10,000 to 40,000 IgE antibodies.

3. Their cytoplasmic granules (secretory vesicles), which

contain physiologically active cytokines (histamine,

serotonin—introduced in chapter 14).

4. Their tendency to degranulate (figures 17.3b and 17.4),

or release the contents of the granules into the tissues

when properly stimulated by allergen.

Let us now see what occurs when sensitized cells are challenged

with allergen a second time.

The Second Contact with Allergen

After sensitization, the IgE-primed mast cells can remain in the tis-

sues for years. Even after long periods without contact, a person

can retain the capacity to react immediately upon reexposure. The

next time allergen molecules contact these sensitized cells, they

bind across adjacent receptors and stimulate degranulation. As

chemical mediators are released, they diffuse into the tissues and

bloodstream. Cytokines give rise to numerous local and systemic

reactions, many of which appear quite rapidly (figure 17.3b). The

symptoms of allergy are not caused by the direct action of allergen

on tissues but by the physiological effects of mast cell mediators on

target organs.

Pollen in Los Angeles

Outlook for January

Trees

: Alder and walnut are blooming extremely early this year.

Black walnut is the worst allergy offender of the walnut family.

Weeds

: Weed season has finally ended.

Grasses

: Grasses will be mostly dormant until late February,

early March.

Molds

: Molds will continue to be sporadic and with major increases

following periods of precipitation.

Weekly Levels for December

Major

Moderate

Minor

Trees

Weeds

Grasses

Mold spores

Week 1

Week 2

Week 3

Week 4

(a)

(b)

(c)

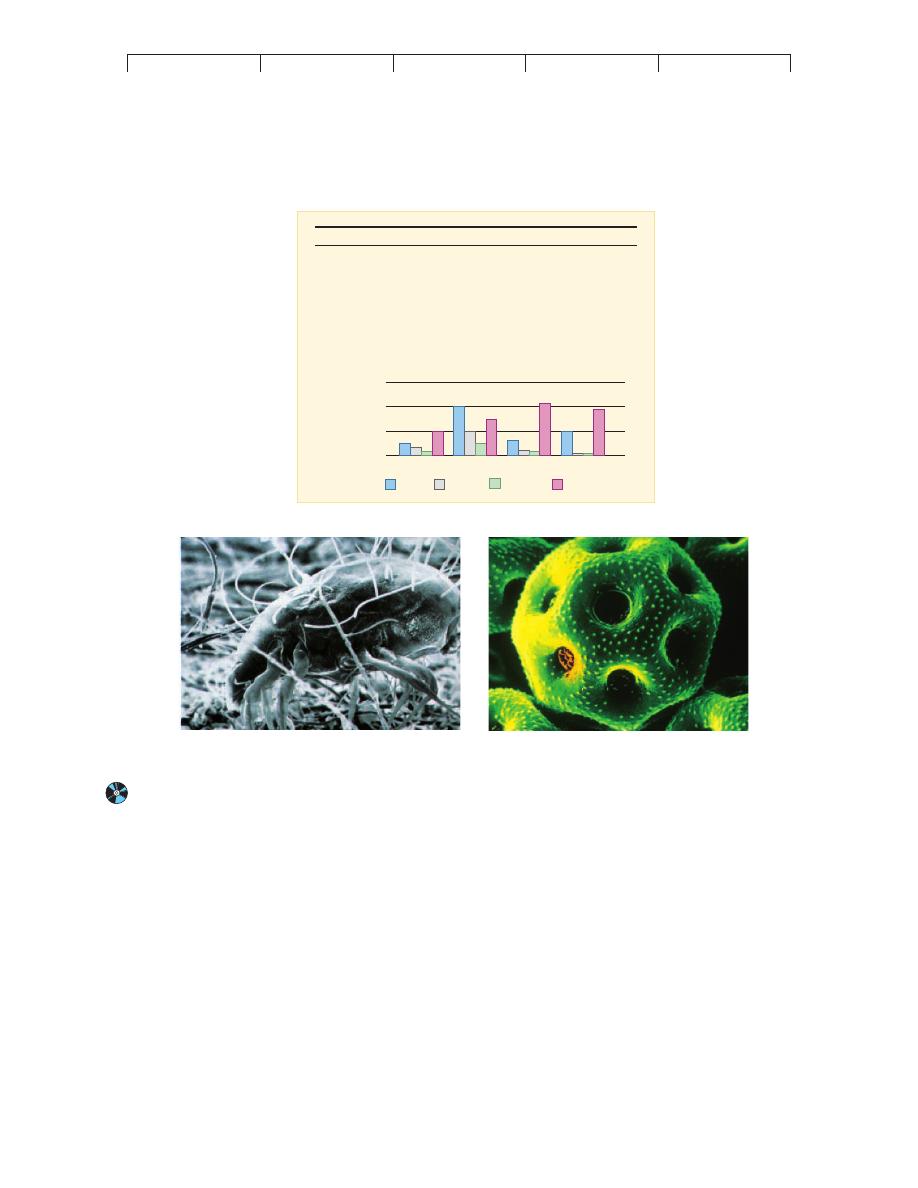

FIGURE 17.2

Monitoring airborne allergens.

(a) The air in heavily vegetated places with a mild climate is especially laden with allergens such as pollen and

mold spores. In just one month in southern California, weed pollen subsided to near zero and mold spore levels doubled. (b) Because the dust mite

Dermatophagoides feeds primarily on human skin cells in house dust, these mites are found in abundance in bedding and carpets. Airborne mite feces

and particles from their bodies are an important source of allergies. (c) Scanning electron micrograph of a single pollen grain from a rose (6,000!).

Millions of these are released from a single flower.

(a) Source: Data from the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America, Los Angeles, CA.

Talaro−Talaro: Foundations

in Microbiology, Fourth

Edition

17. Disorders in Immunity

Text

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2002

502

CHAPTER 17 Disorders in Immunity

CYTOKINES, TARGET ORGANS,

AND ALLERGIC SYMPTOMS

Numerous substances involved in mediating allergy (and inflam-

mation) have been identified. The principal chemical mediators

produced by mast cells and basophils are histamine, serotonin, leu-

kotriene, platelet-activating factor, prostaglandins, and bradykinin

(figure 17.4). These chemicals, acting alone or in combination, ac-

count for the tremendous scope of allergic symptoms. For some

theories pertaining to this function of the allergic response, see

Medical Microfile 17.1. Targets of these mediators include the skin,

upper respiratory tract, gastrointestinal tract, and conjunctiva. The

general responses of these organs include rashes, itching, redness,

rhinitis, sneezing, diarrhea, and shedding of tears. Systemic targets

include smooth muscle, mucous glands, and nervous tissue. Be-

cause smooth muscle is responsible for regulating the size of blood

vessels and respiratory passageways, changes in its activity can

profoundly alter blood flow, blood pressure, and respiration. Pain,

anxiety, agitation, and lethargy are also attributable to the effects of

mediators on the nervous system.

Histamine* is the most profuse and fastest-acting allergic

mediator. It is a potent stimulator of smooth muscle, glands, and

eosinophils. Histamine’s actions on smooth muscle vary with lo-

cation. It constricts the smooth muscle layers of the small bronchi

and intestine, thereby causing labored breathing and increased

Allergen particles enter

Lymphatic vessel

carries them to

Lymph node

B cell recognizes

allergen

Fc fragments

Mast cell in tissue

IgE binds to

mast cell surface

Granules

with

inflammatory

mediators

Time

Sensitization/IgE Production

Degranulation

st

im

ul

at

es

Mast cells

trigg

ers

Allergen particle is encountered again

End result: Symptoms in various organs

Red, itchy eyes

Hives

Runny

nose

Subsequent Exposure to Allergen

Systemic distribution of

mediators in bloodstream

proliferates

into

Plasma cells

Synthesize

IgE

B cell

(b)

(a)

FIGURE 17.3

A schematic view of cellular reactions during the type I allergic response.

(a) Sensitization (initial contact with sensitizing dose).

(b) Provocation (later contacts with provocative dose).

*

histamine

(his´-tah-meen) Gr. histio, tissue, and amine.