Talaro−Talaro: Foundations

in Microbiology, Fourth

Edition

17. Disorders in Immunity

Text

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2002

502

CHAPTER 17 Disorders in Immunity

CYTOKINES, TARGET ORGANS,

AND ALLERGIC SYMPTOMS

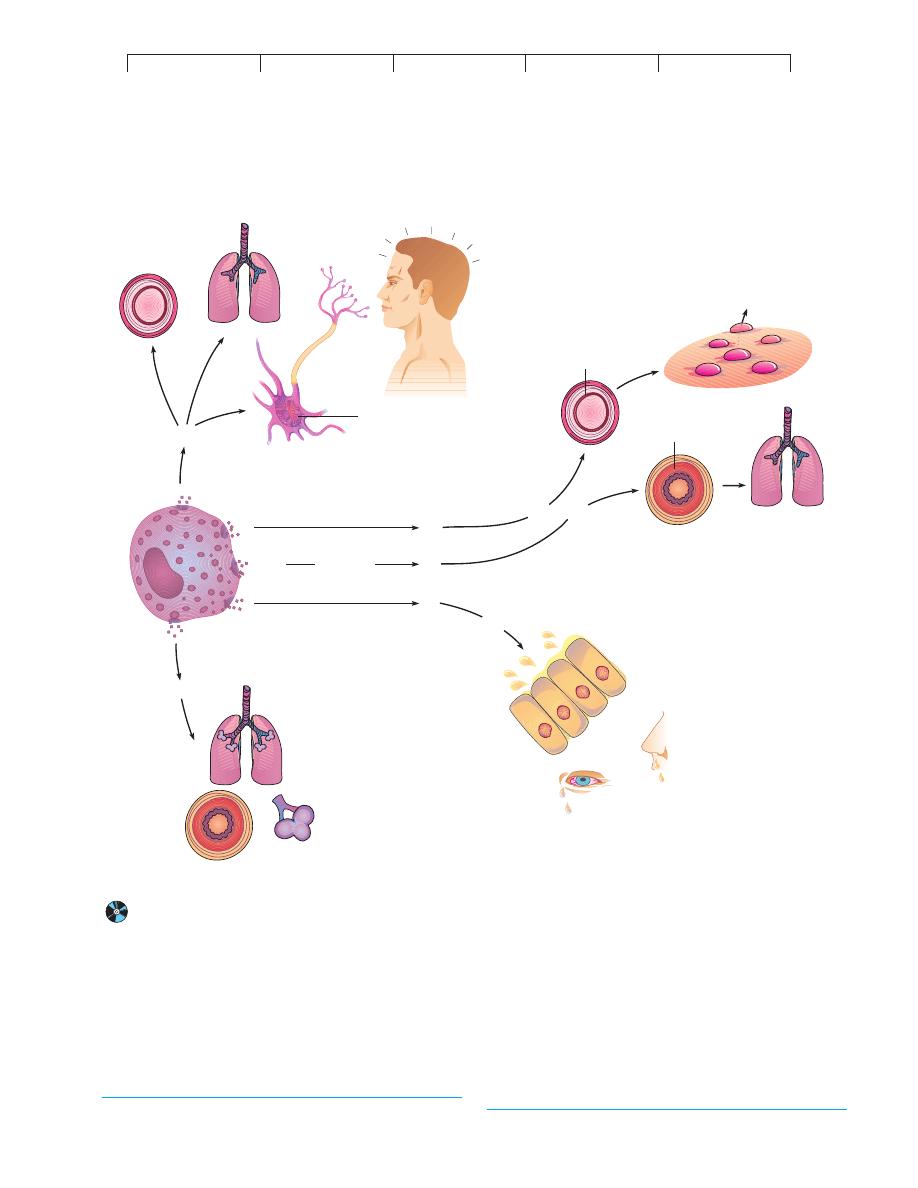

Numerous substances involved in mediating allergy (and inflam-

mation) have been identified. The principal chemical mediators

produced by mast cells and basophils are histamine, serotonin, leu-

kotriene, platelet-activating factor, prostaglandins, and bradykinin

(figure 17.4). These chemicals, acting alone or in combination, ac-

count for the tremendous scope of allergic symptoms. For some

theories pertaining to this function of the allergic response, see

Medical Microfile 17.1. Targets of these mediators include the skin,

upper respiratory tract, gastrointestinal tract, and conjunctiva. The

general responses of these organs include rashes, itching, redness,

rhinitis, sneezing, diarrhea, and shedding of tears. Systemic targets

include smooth muscle, mucous glands, and nervous tissue. Be-

cause smooth muscle is responsible for regulating the size of blood

vessels and respiratory passageways, changes in its activity can

profoundly alter blood flow, blood pressure, and respiration. Pain,

anxiety, agitation, and lethargy are also attributable to the effects of

mediators on the nervous system.

Histamine* is the most profuse and fastest-acting allergic

mediator. It is a potent stimulator of smooth muscle, glands, and

eosinophils. Histamine’s actions on smooth muscle vary with lo-

cation. It

constricts the smooth muscle layers of the small bronchi

and intestine, thereby causing labored breathing and increased

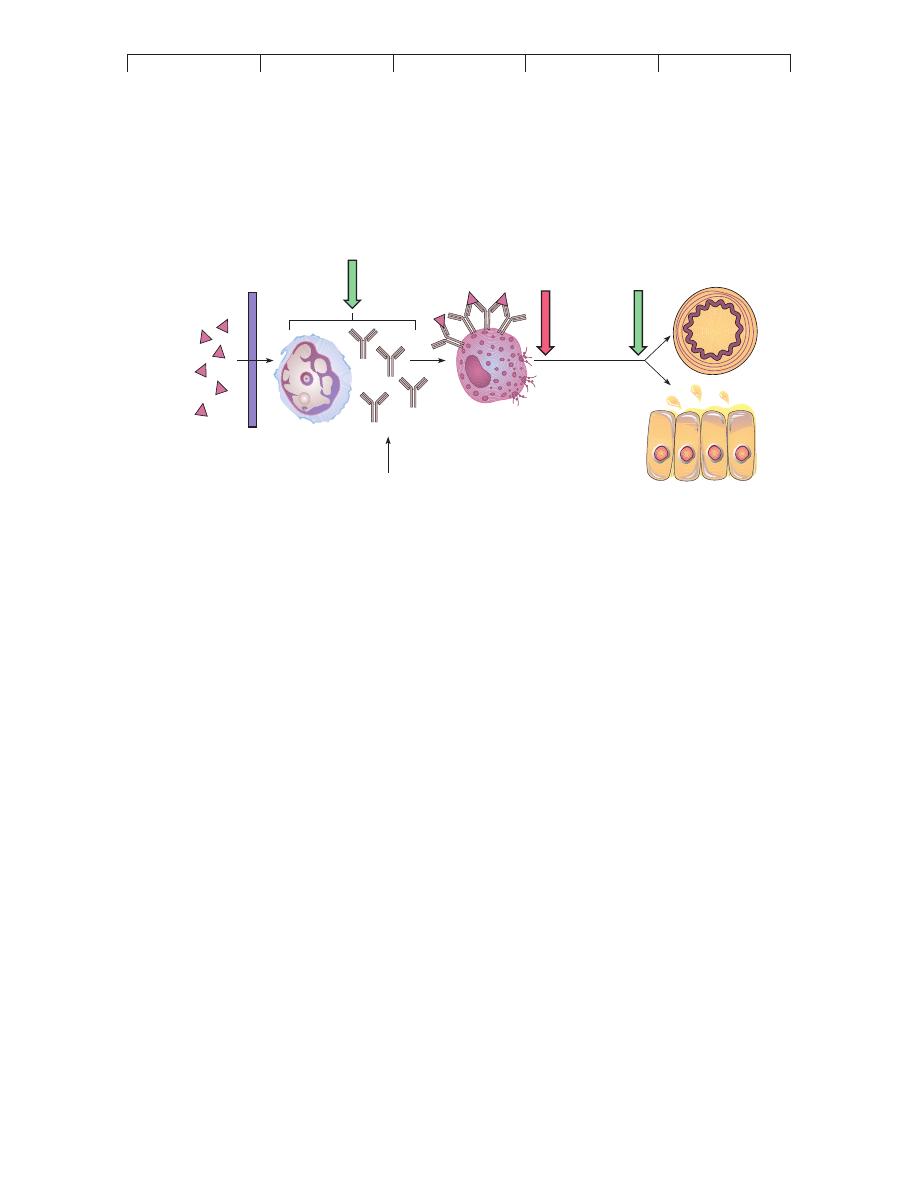

Allergen particles enter

Lymphatic vessel

carries them to

Lymph node

B cell recognizes

allergen

Fc fragments

Mast cell in tissue

IgE binds to

mast cell surface

Granules

with

inflammatory

mediators

Time

Sensitization/IgE Production

Degranulation

st

im

ul

at

es

Mast cells

trigg

ers

Allergen particle is encountered again

End result: Symptoms in various organs

Red, itchy eyes

Hives

Runny

nose

Subsequent Exposure to Allergen

Systemic distribution of

mediators in bloodstream

proliferates

into

Plasma cells

Synthesize

IgE

B cell

(b)

(a)

FIGURE 17.3

A schematic view of cellular reactions during the type I allergic response.

(a) Sensitization (initial contact with sensitizing dose).

(b) Provocation (later contacts with provocative dose).

*

histamine

(his´-tah-meen) Gr.

histio, tissue, and amine.

Talaro−Talaro: Foundations

in Microbiology, Fourth

Edition

17. Disorders in Immunity

Text

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2002

Type I Allergic Reactions: Atopy and Anaphylaxis

503

intestinal motility. In contrast, histamine

relaxes vascular smooth

muscle and dilates arterioles and venules. It is responsible for the

wheal* and flare reaction in the skin (see figure 17.6a), pruritis

(itching), and headache. More severe reactions (such as anaphy-

laxis) can be accompanied by edema and vascular dilation, which

lead to hypotension, tachycardia, circulatory failure, and, fre-

quently, shock. Salivary, lacrimal, mucous, and gastric glands are

also histamine targets.

Although the role of

serotonin* in human allergy is uncer-

tain, its effects appear to complement those of histamine. In exper-

imental animals, serotonin increases vascular permeability, capil-

lary dilation, smooth muscle contraction, intestinal peristalsis, and

respiratory rate, but it diminishes central nervous system activity.

Dilated blood vessel

Constricted

bronchiole

Smooth muscle

Leukotriene

Glands

Prostaglandin

Typical

response

in asthma

Nerve cell

Dilated

blood vessel

Constricted bronchioles

Headache

Wheal and flare

reaction, itching

Wheezing,

difficult breathing

Excessive mucus and

glandular secretions

Constriction

of bronchioles

Plugged

alveoli

D

e

g

ra

n

u

la

ti

o

n

Histamine

Serotonin

Bradykinin

FIGURE 17.4

The spectrum of reactions to inflammatory cytokines and the common symptoms they elicit in target tissues and organs.

Note the

extensive overlapping effects.

*

serotonin

(ser

-oh-toh-nin) L. serum, whey, and tonin, tone.

*

wheal

(weel) A smooth, slightly elevated, temporary welt that is surrounded by a

flushed patch of skin (flare).

Talaro−Talaro: Foundations

in Microbiology, Fourth

Edition

17. Disorders in Immunity

Text

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2002

504

CHAPTER 17 Disorders in Immunity

Before the specific types were identified,

leukotriene* was

known as the “slow-reacting substance of anaphylaxis” for its

property of inducing gradual contraction of smooth muscle. This

type of leukotriene is responsible for the prolonged bronchospasm,

vascular permeability, and mucous secretion of the asthmatic indi-

vidual. Other leukotrienes stimulate the activities of polymor-

phonuclear leukocytes.

Platelet-activating factor is a lipid released by basophils,

neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages that causes platelet

aggregation and lysis. The physiological response to stimulation by

this factor is similar to that of histamine, including increased

vascular permeability, pulmonary smooth muscle contraction,

pulmonary edema, hypotension, and a wheal and flare response in

the skin.

Prostaglandins* are a group of powerful inflammatory

agents. Normally, these substances regulate smooth muscle con-

traction (for example, they stimulate uterine contractions during

delivery). In allergic reactions, they are responsible for vasodila-

tion, increased vascular permeability, increased sensitivity to pain,

and bronchoconstriction. Certain anti-inflammatory drugs work by

preventing the actions of prostaglandins.

Bradykinin* is related to a group of plasma and tissue

peptides known as kinins that participate in blood clotting and

chemotaxis. In allergy, it causes prolonged smooth muscle contrac-

tion of the bronchioles, dilatation of peripheral arterioles, increased

capillary permeability, and increased mucous secretion.

SPECIFIC DISEASES ASSOCIATED WITH IgE-

AND MAST CELL-MEDIATED ALLERGY

The mechanisms just described are basic to hay fever, allergic

asthma, food allergy, drug allergy, eczema, and anaphylaxis. In this

section, we cover the main characteristics of these conditions, fol-

lowed by methods of detection and treatment.

Atopic Diseases

Hay fever is a generic term for allergic rhinitis,* a seasonal reac-

tion to inhaled plant pollen or molds, or a chronic, year-round

reaction to a wide spectrum of airborne allergens or inhalants (see

table 17.2). The targets are typically respiratory membranes, and

the symptoms include nasal congestion; sneezing; coughing; pro-

fuse mucous secretion; itchy, red, and teary eyes; and mild bron-

choconstriction.

Asthma* is a respiratory disease characterized by episodes

of impaired breathing due to severe bronchoconstriction. The air-

ways of asthmatic people are exquisitely responsive to minute

amounts of inhalant allergens, food, or other stimuli, such as in-

fectious agents. The symptoms of asthma range from occasional,

annoying bouts of difficult breathing to fatal suffocation. Labored

breathing, shortness of breath, wheezing, cough, and ventilatory

rales* are present to one degree or another. The respiratory tract

of an asthmatic person is chronically inflamed and severely over-

reactive to allergy chemicals, especially leukotrienes and sero-

tonin from pulmonary mast cells. Other pathologic components

are thick mucous plugs in the air sacs and lung damage that can

result in long-term respiratory compromise. An imbalance in the

nervous control of the respiratory smooth muscles is apparently

involved in asthma, and the episodes are influenced by the psy-

chological state of the person, which strongly supports a neuro-

logical connection.

The number of asthma sufferers in the United States is esti-

mated at 10 million, with nearly one-third of them children. For

reasons that are not completely understood, asthma is on the in-

crease, and deaths from it have doubled since 1982, even though

effective agents to control it are more available now than they

have ever been before. A recent study of inner-city children has

correlated high levels of asthma to contact with cockroach anti-

gens in their living quarters. Nearly 40% of children age 10 or

younger showed extreme sensitivity to the droppings and remains

of these insects.

MEDICAL MICROFILE

17.1

Of What Value Is Allergy?

this system is to defend against helminth worms that are ubiquitous

human parasites. In chapter 14, we learned that inflammatory mediators

serve valuable functions, such as increasing blood flow and vascular

permeability to summon essential immune components to an injured site.

They are also responsible for increased mucous secretion, gastric motil-

ity, sneezing, and coughing, which help expel noxious agents. The

difference is that, in allergic persons, the quantity and quality of these

reactions are excessive and uncontrolled.

Why would humans and other mammals evolve an allergic response that

is capable of doing so much harm and even causing death? It is unlikely

that this limb of immunity exists merely to make people miserable; it

must have a role in protection and survival. What are the underlying bio-

logical functions of IgE, mast cells, and the array of potent cytokines?

Analysis has revealed that, although allergic persons have high levels of

IgE, trace quantities are present even in the sera of nonallergic individu-

als, just as mast cells and inflammatory chemicals are also part of normal

human physiology. It is generally believed that one important function of

*

leukotriene

(loo

-koh-try-een) Gr. leukos, white blood cell, and triene, a chemical

suffix.

*

prostaglandin

(pross

-tah-glan-din) From prostate gland. The substance was

originally isolated from semen.

*

bradykinin

(brad

-ee-kye-nin) Gr. bradys, slow, and kinein, to move.

*

rhinitis

(rye-nye

-tis) Gr. rhis, nose, and itis, inflammation.

*

asthma

(az

-muh) The Greek word for gasping.

*

rales

(rails) Abnormal breathing sounds.

Talaro−Talaro: Foundations

in Microbiology, Fourth

Edition

17. Disorders in Immunity

Text

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2002

Type I Allergic Reactions: Atopy and Anaphylaxis

505

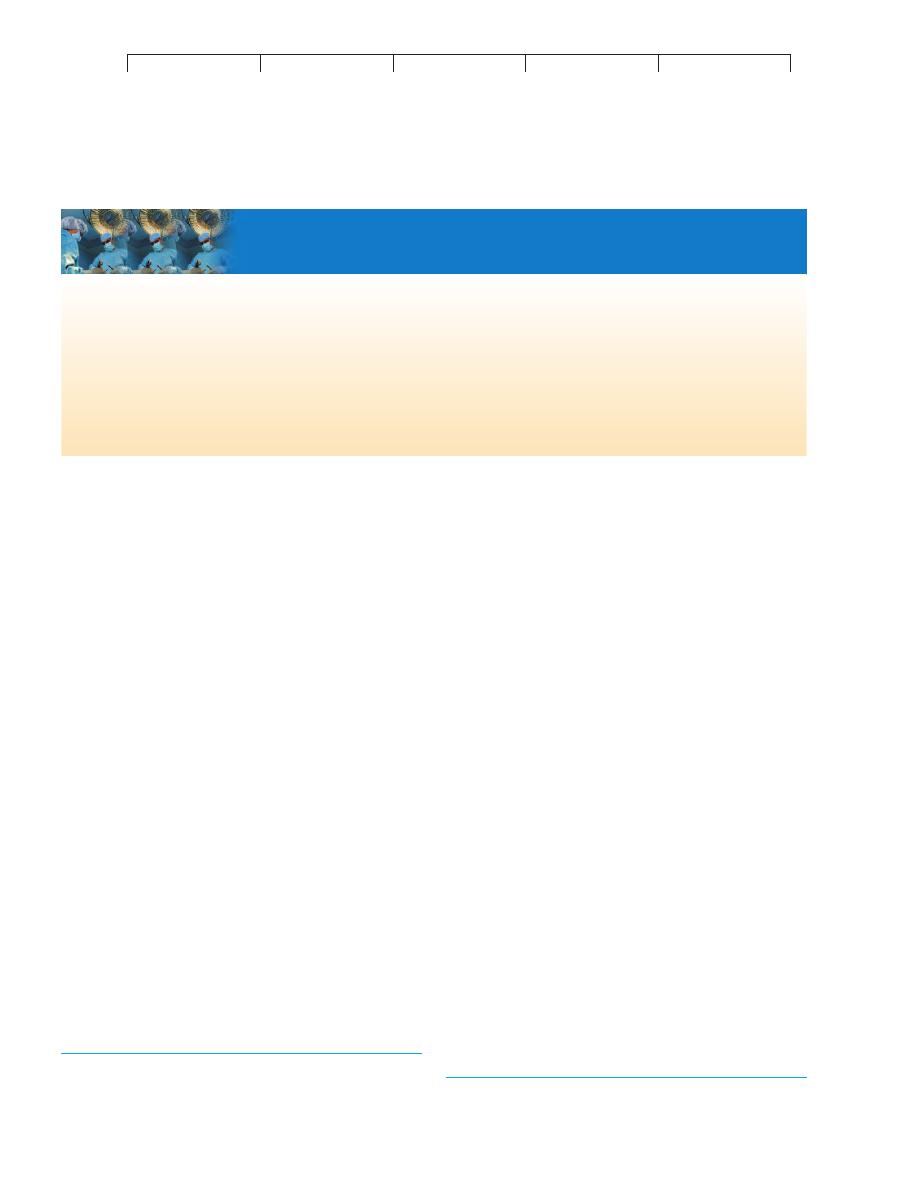

Atopic dermatitis is an intensely itchy inflammatory condi-

tion of the skin, sometimes also called

eczema.* Sensitization

occurs through ingestion, inhalation, and, occasionally, skin con-

tact with allergens. It usually begins in infancy with reddened,

vesicular, weeping, encrusted skin lesions. It then progresses in

childhood and adulthood to a dry, scaly, thickened skin condition

(figure 17.5). Lesions can occur on the face, scalp, neck, and inner

surfaces of the limbs and trunk. The itchy, painful lesions cause

considerable discomfort, and they are often predisposed to second-

ary bacterial infections. An anonymous writer once aptly described

eczema as “the itch that rashes’’ or “one scratch is too many but one

thousand is not enough.’’

Food Allergy

The ordinary diet contains a vast variety of compounds that are po-

tentially allergenic. It is generally believed that food allergies are

due to a digestive product of the food or to an additive (preservative

or flavoring). Although the mode of entry is intestinal, food aller-

gies can also affect the skin and respiratory tract. Gastrointestinal

symptoms include vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. In se-

vere cases, nutrients are poorly absorbed, leading to growth retar-

dation and failure to thrive in young children. Other manifestations

of food allergies include eczema, hives, rhinitis, asthma, and occa-

sionally, anaphylaxis. Classic food hypersensitivity involves IgE

and degranulation of mast cells, but not all reactions involve this

FIGURE 17.5

Atopic dermatitis, or eczema.

Vesicular, encrusted lesions are typical

in afflicted infants. This condition is prevalent enough to account for 1%

of pediatric care.

*

eczema

(eks

-uh-mah; also ek-zeem-uh) Gr. ekzeo, to boil over.

mechanism. The most common food allergens come from peanuts,

fish, cow’s milk, eggs, shellfish, and soybeans.

Drug Allergy

Modern chemotherapy has been responsible for many medical ad-

vances. Unfortunately, it has also been hampered by the fact that

drugs are foreign compounds capable of stimulating allergic

reactions. In fact, allergy to drugs is one of the most common side

effects of treatment (present in 5–10% of hospitalized patients).

Depending upon the allergen, route of entry, and individual sensi-

tivities, virtually any tissue of the body can be affected, and reac-

tions range from mild atopy to fatal anaphylaxis. Compounds im-

plicated most often are antibiotics (penicillin is number one in

prevalence), synthetic antimicrobics (sulfa drugs), aspirin, opiates,

and anaesthetics. The actual allergen is not the intact drug itself but

a hapten given off when the liver processes the drug. Some forms

of penicillin sensitivity are due to the presence of small amounts of

the drug in meat, milk, and other foods and to exposure to

Penicil-

lium mold in the environment.

ANAPHYLAXIS: AN OVERPOWERING

SYSTEMIC REACTION

The term

anaphylaxis, or anaphylactic shock, was first used to

denote a reaction of animals injected with a foreign protein. Al-

though the animals showed no response during the first contact,

upon reinoculation with the same protein at a later time, they ex-

hibited acute symptoms—itching, sneezing, difficult breathing,

prostration, and convulsions—and many died in a few minutes.

Two clinical types of anaphylaxis are distinguished in humans.

Cu-

taneous anaphylaxis is the wheal and flare inflammatory reaction to

the local injection of allergen.

Systemic anaphylaxis, on the other

hand, is characterized by sudden respiratory and circulatory disrup-

tion that can be fatal in a few minutes. In humans, the allergen and

route of entry are variable, though bee stings and injections of an-

tibiotics or serum are implicated most often. Bee venom is a com-

plex material containing several allergens and enzymes that can

create a sensitivity that can last for decades after exposure.

The underlying physiological events in systemic anaphylaxis

parallel those of atopy, but the concentration of chemical mediators

and the strength of the response are greatly amplified. The immune

system of a sensitized person exposed to a provocative dose of al-

lergen responds with a sudden, massive release of chemicals into

the tissues and blood, which act rapidly on the target organs. Ana-

phylactic persons have been known to die in 15 minutes from com-

plete airway blockage.

DIAGNOSIS OF ALLERGY

Because allergy mimics infection and other conditions, it is impor-

tant to determine if a person is actually allergic. If possible or nec-

essary, it is also helpful to identify the specific allergen or allergens.

Allergy diagnosis involves several levels of tests, including non-

specific, specific,

in vitro, and in vivo methods.

A new test that can distinguish whether a patient has experi-

enced an allergic attack measures elevated blood levels of tryptase,

an enzyme released by mast cells that increases during an allergic

response. Several types of specific

in vitro tests can determine

Talaro−Talaro: Foundations

in Microbiology, Fourth

Edition

17. Disorders in Immunity

Text

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2002

506

CHAPTER 17 Disorders in Immunity

the allergic potential of a patient’s blood sample. The leukocyte

histamine-release test measures the amount of histamine released

from the patient’s basophils when exposed to a specific allergen.

Serological tests that use radioimmune assays (see chapter 16) to

reveal the quantity and quality of IgE are also clinically helpful.

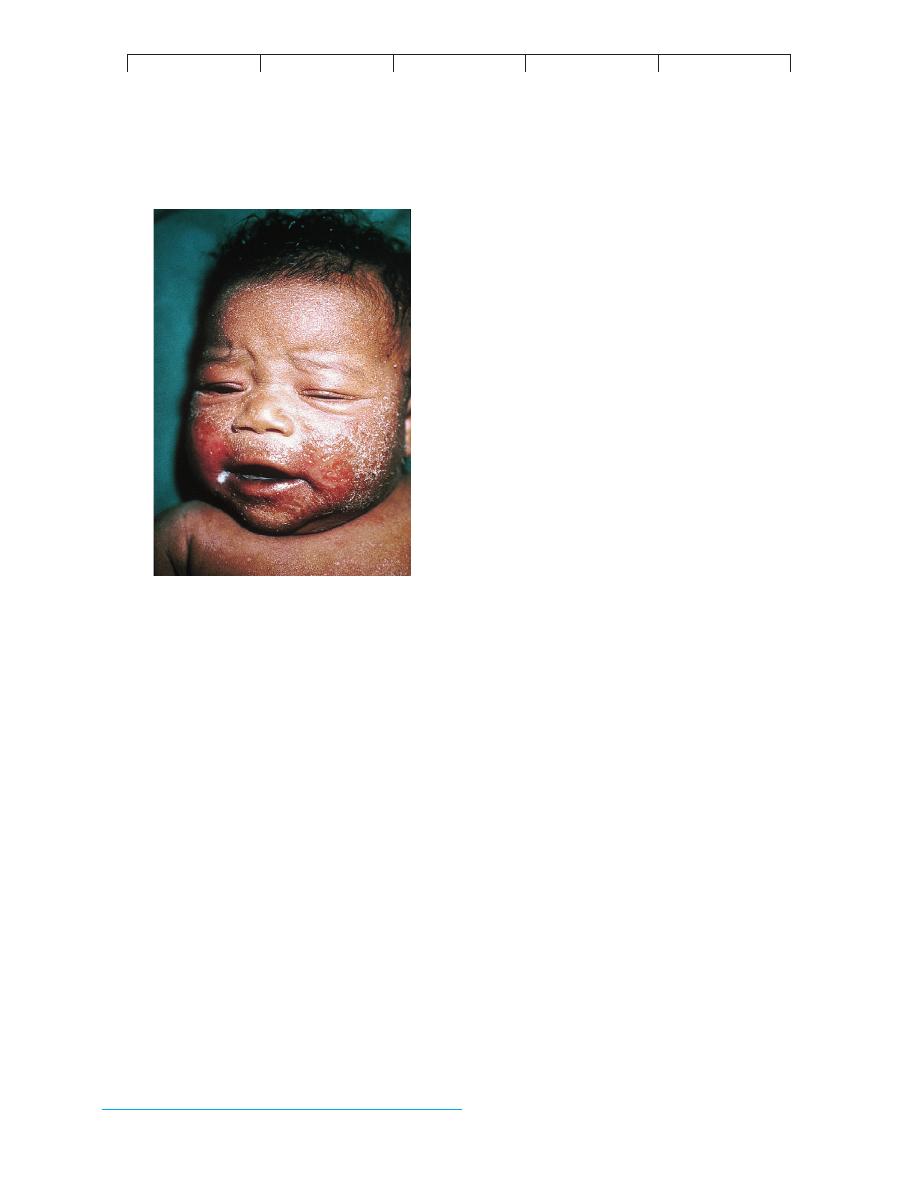

Skin Testing

A useful

in vivo method to detect precise atopic or anaphylactic

sensitivities is skin testing. With this technique, a patient’s skin is

injected, scratched, or pricked with a small amount of a pure al-

lergen extract. Hundreds of these allergen extracts contain com-

mon airborne allergens (plant and mold pollen) and more unusual

allergens (mule dander, theater dust, bird feathers). Unfortu-

nately, skin tests for food allergies using food extracts are unreli-

able in most cases. In patients with numerous allergies, the aller-

gist maps the skin on the inner aspect of the forearms or back and

injects the allergens intradermally according to this predeter-

mined pattern (figure 17.6

a). Approximately 20 minutes after

antigenic challenge, each site is appraised for a wheal response

indicative of histamine release. The diameter of the wheal is

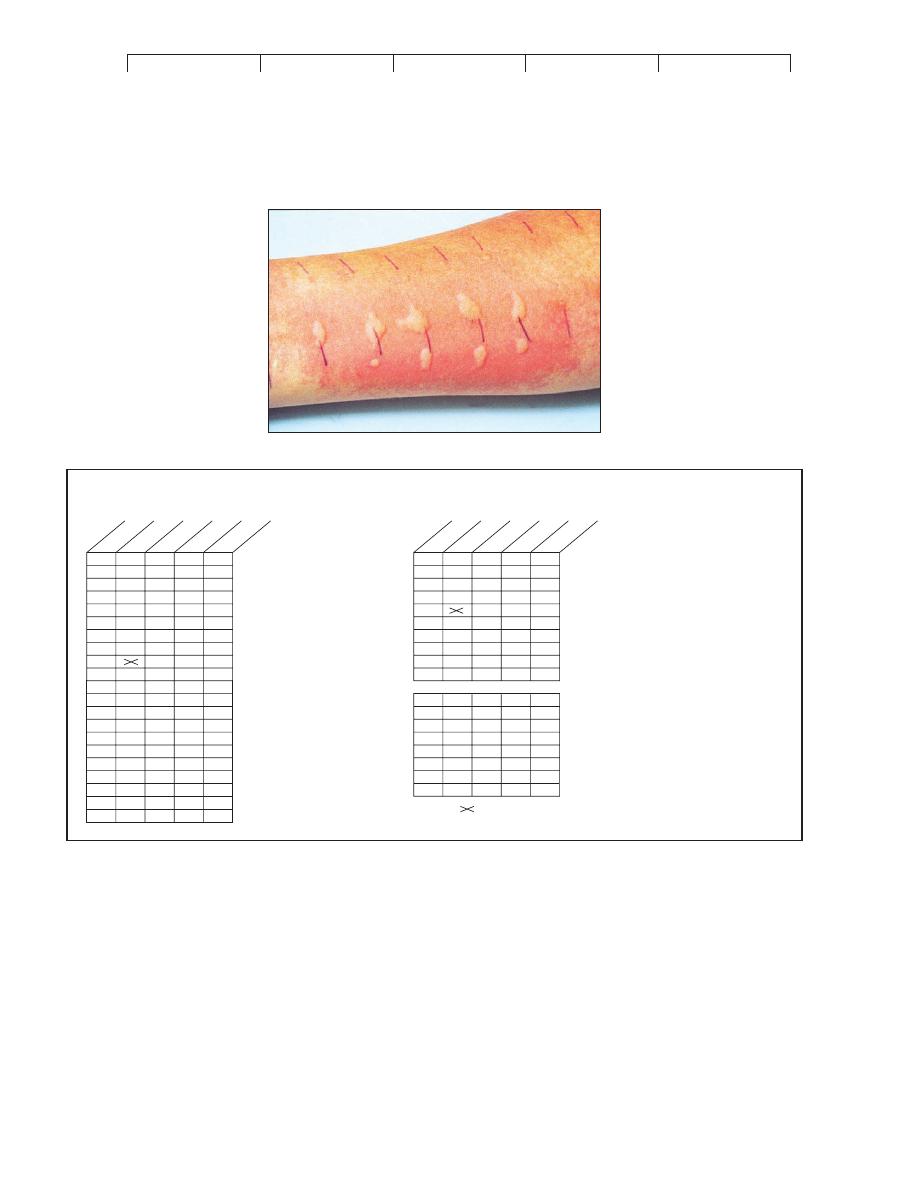

(a)

Environmental Allergens

1. Acacia gum

2. Cat dander

3. Chicken feathers

4. Cotton lint

5. Dog dander

6. Duck feathers

7. Glue, animal

8. Horse dander

9. Horse serum

10. House dust #1

11. Kapok

12. Mohair (goat)

13. Paper

14. Pyrethrum

15. Rug pad, ozite

16. Silk dust

17. Tobacco dust

18. Tragacanth gum

19. Upholstery dust

20. Wool

No. 1 Standard Series

1. Ant

2. Aphis

3. Bee

4. Housefly

5. House mite

6. Mosquito

7. Moth

8. Roach

9. Wasp

10. Yellow jacket

Airborne mold spores

11.

Alternaria

12.

Aspergillus

13.

Cladosporium

14.

Hormodendrum

15.

Penicillium

16.

Phoma

17.

Rhizopus

18. .........................

No. 2 Airborne Particles

+++

+++

++++

++++

++

+

+

++

+++

+

+

+

++++

+++

+

+

+

+++++

+++

ID 8/85

+++

+++++

++++

++++

+++

++++

+++

++

0

ID 8/85

++

+++

++

+++

0

+

+++

0

+

++

+++

++++

- not done

- no reaction

- slight reaction

- mild reaction

- moderate reaction

- severe reaction

FIGURE 17.6

A method for conducting an allergy skin test.

The forearm (or back) is mapped and then injected with a selection of allergen extracts.

The allergist must be very aware of potential anaphylaxis attacks triggered by these injections. (a) Close-up of skin wheals showing a number of

positive reactions (dark lines are measurer’s marks). (b) An actual skin test record for some common environmental allergens with a legend for

assessing them.

(b)

Talaro−Talaro: Foundations

in Microbiology, Fourth

Edition

17. Disorders in Immunity

Text

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2002

Type I Allergic Reactions: Atopy and Anaphylaxis

507

measured and rated on a scale of 0 (no reaction) to 4

" (greater

than 15 mm). Figure 17.6

b shows skin test results for a person

with extreme inhalant allergies.

TREATMENT AND PREVENTION OF ALLERGY

In general, the methods of treating and preventing type I allergy in-

volve (1) avoiding the allergen, though this may be very difficult in

many instances; (2) taking drugs that block the action of lympho-

cytes, mast cells, or chemical mediators; and (3) undergoing desen-

sitization therapy.

It is not possible to completely prevent initial sensitization,

since there is no way to tell in advance if a person will develop an

allergy to a particular substance. The practice of delaying the intro-

duction of solid foods apparently has some merit in preventing food

allergies in children, though even breast milk can contain allergens

ingested by the mother. Although rigorous cleaning and air condi-

tioning can reduce contact with airborne allergens, it is not feasible

to isolate a person from all allergens, which is the reason drugs are

so important in control.

Therapy to Counteract Allergies

The aim of antiallergy medication is to block the progress of the

allergic response somewhere along the route between IgE produc-

tion and the appearance of symptoms (figure 17.7). Oral anti-

inflammatory drugs such as corticosteroids inhibit the activity of

lymphocytes and thereby reduce the production of IgE, but they also

have dangerous side effects and should not be taken for prolonged

periods. Some drugs block the degranulation of mast cells and

reduce the levels of inflammatory cytokines. The most effective of

these are diethylcarbamazine and cromolyn. Asthma and rhinitis

sufferers can find relief with a new drug that blocks synthesis of

leukotriene and a monoclonal antibody that inactivates IgE (Xolair).

Widely used medications for preventing symptoms of

atopic allergy are

antihistamines, the active ingredients in most

over-the-counter allergy-control drugs. Antihistamines interfere

with histamine activity by binding to histamine receptors on tar-

get organs. Most of them have major side effects, however, such

as drowsiness. Newer antihistamines lack this side effect because

they do not cross the blood-brain barrier. Other drugs that relieve

inflammatory symptoms are aspirin and acetaminophen, which

reduce pain by interfering with prostaglandin, and theophylline, a

bronchodilator that reverses spasms in the respiratory smooth

muscles. Persons who suffer from anaphylactic attacks are urged

to carry at all times injectable epinephrine (adrenaline) and an

identification tag indicating their sensitivity. An aerosol inhaler

containing epinephrine can also provide rapid relief. Epinephrine

reverses constriction of the airways and slows the release of aller-

gic mediators.

Approximately 70% of allergic patients benefit from con-

trolled injections of specific allergens as determined by skin tests.

This technique, called

desensitization or hyposensitization, is a

therapeutic way to prevent reactions between allergen, IgE, and

mast cells. The allergen preparations contain pure, preserved sus-

pensions of plant antigens, venoms, dust mites, dander, and molds

(but so far, hyposensitization for foods has not proved very effec-

tive). The immunologic basis of this treatment is open to differ-

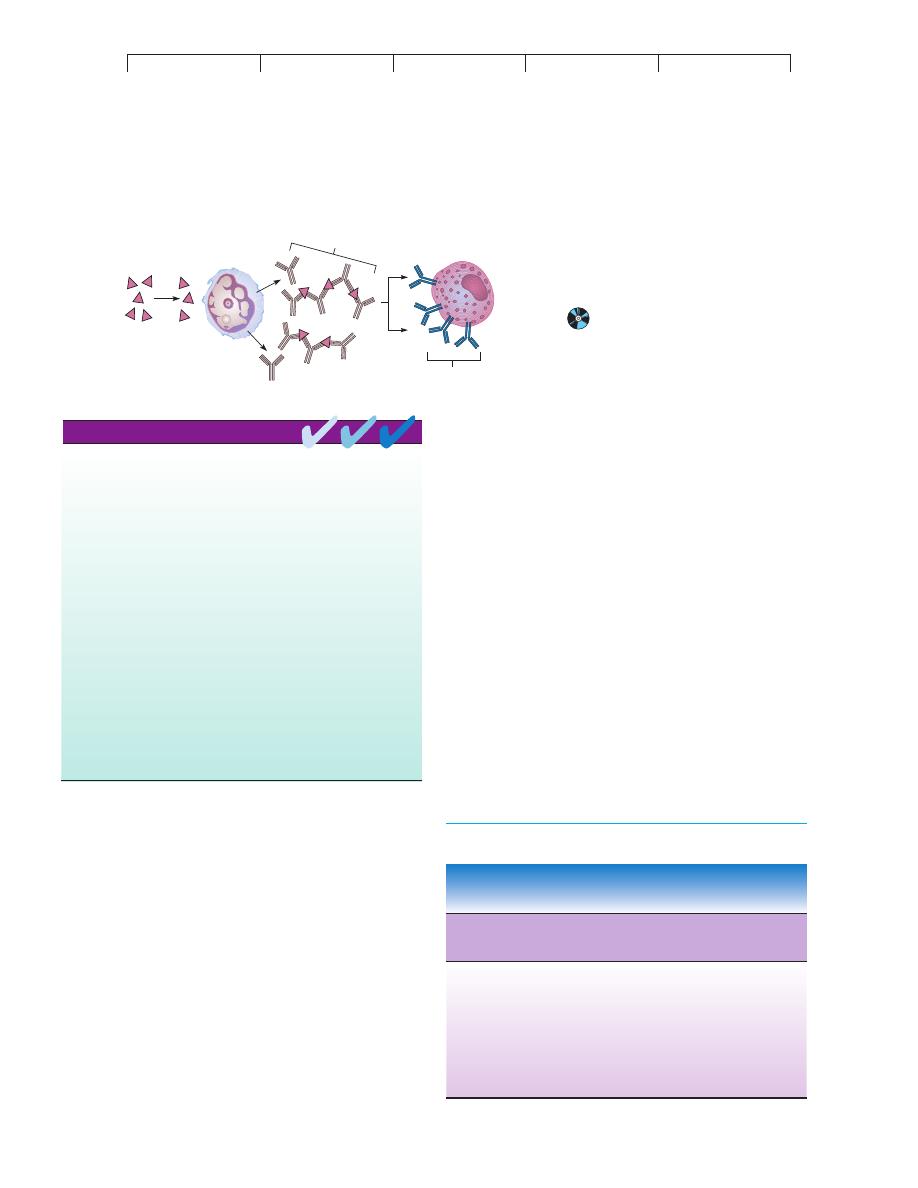

ences in interpretation. One theory suggests that injected aller-

gens stimulate the formation of high levels of allergen-specific

IgG (figure 17.8). It has been proposed that these IgG

blocking

antibodies remove allergen from the system before it can bind to

IgE, thus preventing the degranulation of mast cells. It is also pos-

sible that allergen delivered in this fashion combines with the IgE

itself and prevents it from reacting with the mast cells. Some ex-

perts suggest that the therapy induces specific clones of suppres-

sor T cells to block the production of IgE by B cells.

Avoidance

of allergen

Corticosteroids

keep the plasma cell

from synthesizing IgE

and inhibit T cells.

Allergen

Cromolyn acts

on the surface

of mast cell;

no degranulation

IgE

Antihistamines, aspirin,

epinephrine, theophylline

counteract the effects

of cytokines on targets.

Monoclonal drugs

that inactivate IgE

FIGURE 17.7

Strategies for circumventing allergic attacks.

Talaro−Talaro: Foundations

in Microbiology, Fourth

Edition

17. Disorders in Immunity

Text

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2002

508

CHAPTER 17 Disorders in Immunity

Type II Hypersensitivities: Reactions

That Lyse Foreign Cells

The diseases termed type II hypersensitivities are a complex group

of syndromes that involve complement-assisted destruction (lysis)

of cells by antibodies (IgG and IgM) directed against those cells’

surface antigens. This category includes transfusion reactions and

some types of autoimmunities (discussed in a later section). The

cells targeted for destruction are often red blood cells, but other

cells can be involved.

HUMAN BLOOD TYPES

Chapters 14 and 15 described the functions of unique surface re-

ceptors or markers on cell membranes. Ordinarily, these receptors

play essential roles in transport, recognition, and development, but

they become medically important when the tissues of one person

are placed into the body of another person. Blood transfusions and

organ donations introduce alloantigens (molecules that differ in the

same species) on donor cells that are recognized by the lympho-

cytes of the recipient. These reactions are not really immune dys-

functions as allergy and autoimmunity are. The immune system is

in fact working normally, but it is not equipped to distinguish

between the desirable foreign cells of a transplanted tissue and the

undesirable ones of a microbe.

THE BASIS OF HUMAN ABO

ANTIGENS AND BLOOD TYPES

The existence of human blood types was first demonstrated by an

Austrian pathologist, Karl Landsteiner, in 1904. While studying in-

compatibilities in blood transfusions, he found that the serum of one

person could clump the red blood cells of another. Landsteiner iden-

tified four distinct types, subsequently called the ABO blood groups.

Like the MHC antigens on white blood cells, the ABO anti-

gen markers on red blood cells are genetically determined and com-

posed of glycoproteins. These ABO antigens are inherited as two

(one from each parent) of three alternative

alleles:* A, B, or O. A

and B alleles are dominant over O and codominant with one an-

other. As table 17.3 indicates, this mode of inheritance gives rise to

four blood types (phenotypes), depending on the particular combi-

nation of genes. Thus, a person with an

AA or AO genotype has

type A blood; genotype BB or BO gives type B; genotype AB

Type I hypersensitivity reactions result from excessive IgE production in

response to an exogenous antigen.

The two kinds of type I hypersensitivities are atopy, a chronic, local

allergy, and anaphylaxis, a systemic, potentially fatal allergic response.

The predisposition to type I hypersensitivities is inherited, but age,

geographic locale, and infection also influence allergic response.

Type I allergens include inhalants, ingestants, injectants, and contactants.

The portals of entry for type I antigens are the skin, respiratory tract,

gastrointestinal tract, and genitourinary tract.

Type I hypersensitivities are set up by a sensitizing dose of allergen and

expressed when a second provocative dose triggers the allergic

response. The time interval between the two can be many years.

The primary participants in type I hypersensitivities are IgE, basophils,

mast cells, and agents of the inflammatory response.

Allergies are diagnosed by a variety of in vitro and in vivo tests that

assay specific cells, IgE, and local reactions.

Allergies are treated by medications that interrupt the allergic response at

certain points. Allergic reactions can often be prevented by

desensitization therapy.

CHAPTER CHECKPOINTS

Allergen

IgG

"blocking

antibodies"

B Cell / Plasma Cell

Mast Cell

IgE

No IgE

FIGURE 17.8

The blocking antibody theory for allergic

desensitization.

An injection of allergen

causes IgG antibodies to be formed instead of

IgE; these blocking antibodies cross-link and

effectively remove the allergen before it can react

with the IgE in the mast cell.

TABLE 17.3

Characteristics of ABO Blood Groups

Phenotype A

or B* RBC

Prevalence in

Serum Content

Genotype

Antigen

Population**

of Antibodies

OO

Neither

Most common

Both anti-a

and anti-b

AA, AO

A

Second most

Anti-b

common

BB, BO

B

Third most

Anti-a

common

AB

AB

Least common

Neither

antibody

*Capital letters generally denote antigen; lowercase denotes antibody.

**True of most large populations of mixed racial and ethnic groups.

*

allele

(ah-leel

) Gr. allelon, of one another. An alternate form of a gene for a given trait.