Talaro−Talaro: Foundations

in Microbiology, Fourth

Edition

17. Disorders in Immunity

Text

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2002

508

CHAPTER 17 Disorders in Immunity

Type II Hypersensitivities: Reactions

That Lyse Foreign Cells

The diseases termed type II hypersensitivities are a complex group

of syndromes that involve complement-assisted destruction (lysis)

of cells by antibodies (IgG and IgM) directed against those cells’

surface antigens. This category includes transfusion reactions and

some types of autoimmunities (discussed in a later section). The

cells targeted for destruction are often red blood cells, but other

cells can be involved.

HUMAN BLOOD TYPES

Chapters 14 and 15 described the functions of unique surface re-

ceptors or markers on cell membranes. Ordinarily, these receptors

play essential roles in transport, recognition, and development, but

they become medically important when the tissues of one person

are placed into the body of another person. Blood transfusions and

organ donations introduce alloantigens (molecules that differ in the

same species) on donor cells that are recognized by the lympho-

cytes of the recipient. These reactions are not really immune dys-

functions as allergy and autoimmunity are. The immune system is

in fact working normally, but it is not equipped to distinguish

between the desirable foreign cells of a transplanted tissue and the

undesirable ones of a microbe.

THE BASIS OF HUMAN ABO

ANTIGENS AND BLOOD TYPES

The existence of human blood types was first demonstrated by an

Austrian pathologist, Karl Landsteiner, in 1904. While studying in-

compatibilities in blood transfusions, he found that the serum of one

person could clump the red blood cells of another. Landsteiner iden-

tified four distinct types, subsequently called the ABO blood groups.

Like the MHC antigens on white blood cells, the ABO anti-

gen markers on red blood cells are genetically determined and com-

posed of glycoproteins. These ABO antigens are inherited as two

(one from each parent) of three alternative

alleles:* A, B, or O. A

and B alleles are dominant over O and codominant with one an-

other. As table 17.3 indicates, this mode of inheritance gives rise to

four blood types (phenotypes), depending on the particular combi-

nation of genes. Thus, a person with an

AA or AO genotype has

type A blood; genotype BB or BO gives type B; genotype AB

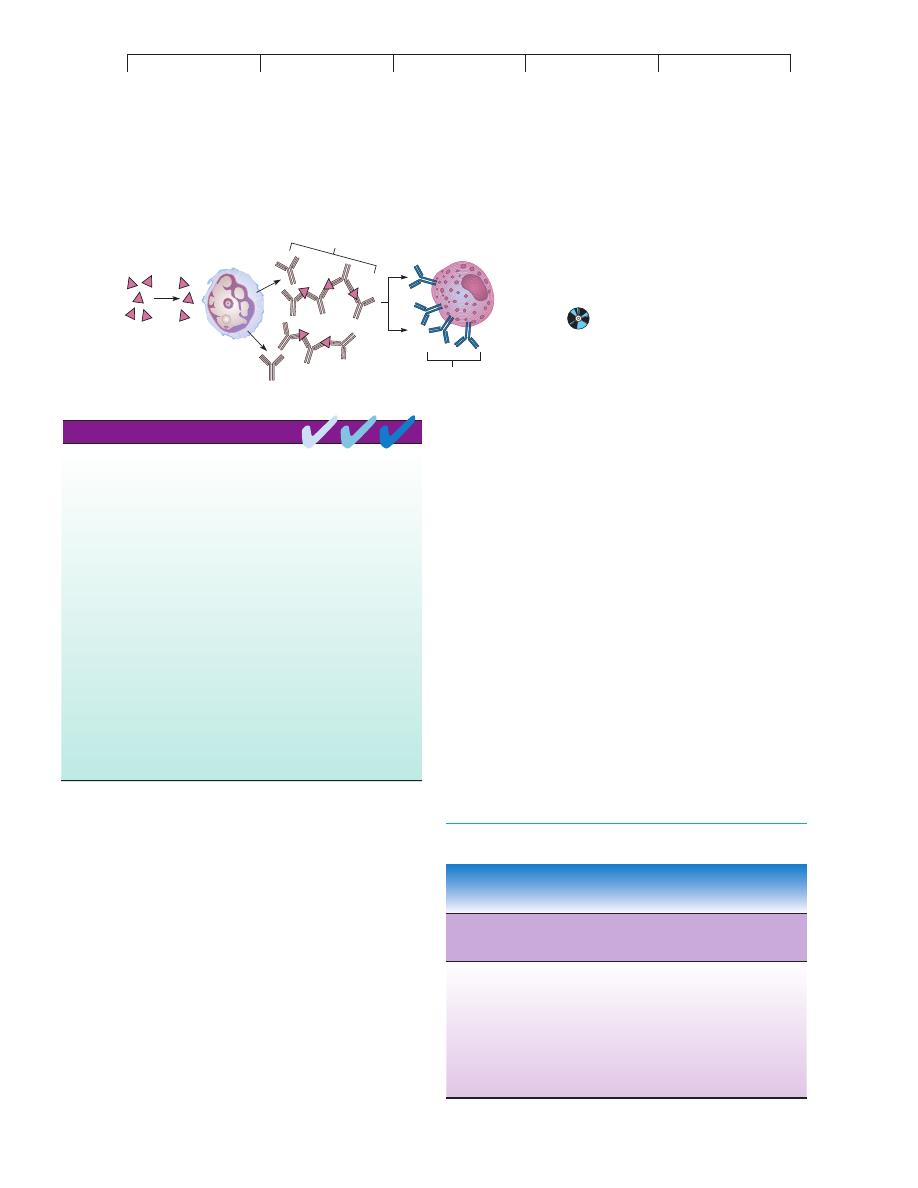

Type I hypersensitivity reactions result from excessive IgE production in

response to an exogenous antigen.

The two kinds of type I hypersensitivities are atopy, a chronic, local

allergy, and anaphylaxis, a systemic, potentially fatal allergic response.

The predisposition to type I hypersensitivities is inherited, but age,

geographic locale, and infection also influence allergic response.

Type I allergens include inhalants, ingestants, injectants, and contactants.

The portals of entry for type I antigens are the skin, respiratory tract,

gastrointestinal tract, and genitourinary tract.

Type I hypersensitivities are set up by a sensitizing dose of allergen and

expressed when a second provocative dose triggers the allergic

response. The time interval between the two can be many years.

The primary participants in type I hypersensitivities are IgE, basophils,

mast cells, and agents of the inflammatory response.

Allergies are diagnosed by a variety of in vitro and in vivo tests that

assay specific cells, IgE, and local reactions.

Allergies are treated by medications that interrupt the allergic response at

certain points. Allergic reactions can often be prevented by

desensitization therapy.

CHAPTER CHECKPOINTS

Allergen

IgG

"blocking

antibodies"

B Cell / Plasma Cell

Mast Cell

IgE

No IgE

FIGURE 17.8

The blocking antibody theory for allergic

desensitization.

An injection of allergen

causes IgG antibodies to be formed instead of

IgE; these blocking antibodies cross-link and

effectively remove the allergen before it can react

with the IgE in the mast cell.

TABLE 17.3

Characteristics of ABO Blood Groups

Phenotype A

or B* RBC

Prevalence in

Serum Content

Genotype

Antigen

Population**

of Antibodies

OO

Neither

Most common

Both anti-a

and anti-b

AA, AO

A

Second most

Anti-b

common

BB, BO

B

Third most

Anti-a

common

AB

AB

Least common

Neither

antibody

*Capital letters generally denote antigen; lowercase denotes antibody.

**True of most large populations of mixed racial and ethnic groups.

*

allele

(ah-leel

) Gr. allelon, of one another. An alternate form of a gene for a given trait.

Talaro−Talaro: Foundations

in Microbiology, Fourth

Edition

17. Disorders in Immunity

Text

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2002

Type II Hypersensitivities: Reactions That Lyse Foreign Cells

509

produces

type AB; and genotype OO produces type O. Some im-

portant points about the blood types are: (1) They are named for the

dominant antigen(s); (2) the RBCs of type O persons have antigens,

but not A and B antigens; and (3) tissues other than RBCs carry A

and B antigens.

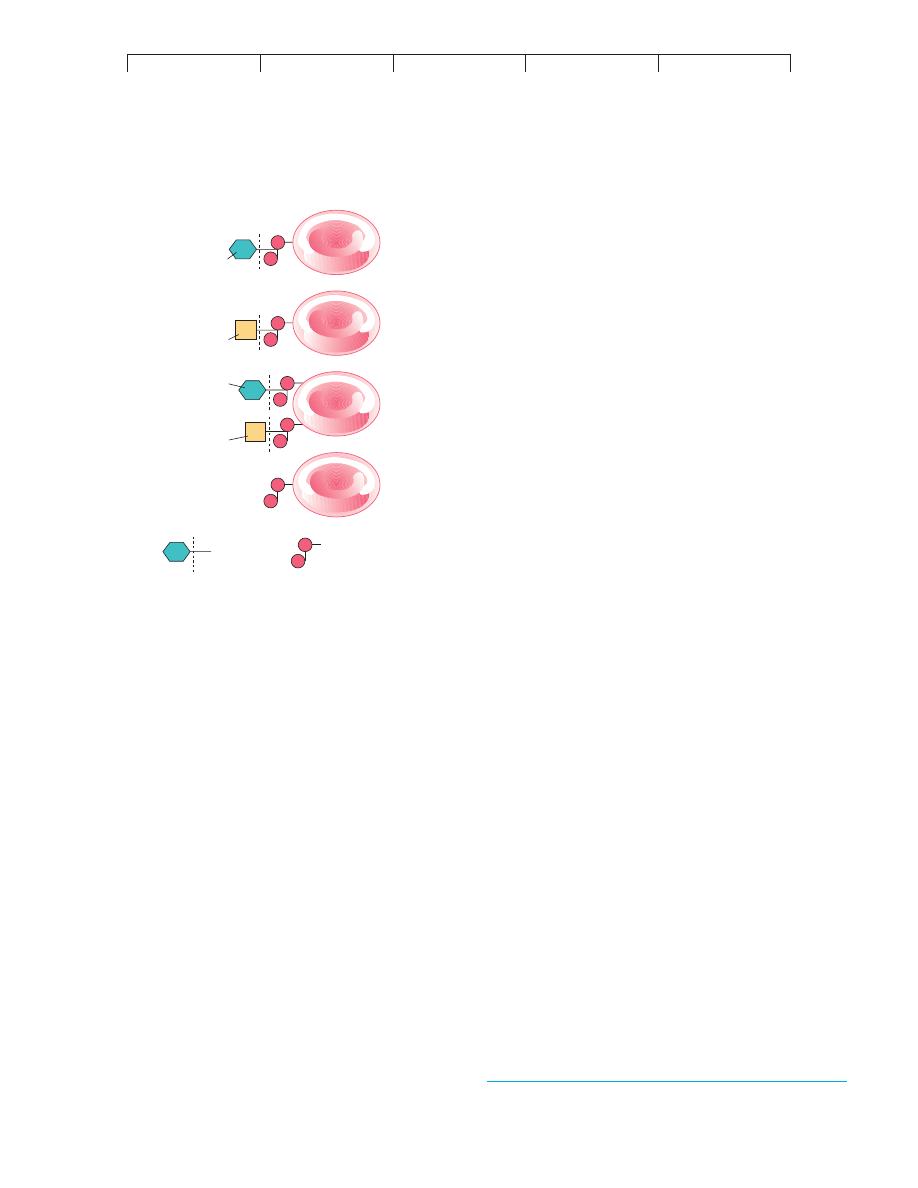

The actual origin of the AB antigens and blood types are

shown in figure 17.9. The A and B genes each code for an enzyme

that adds a terminal carbohydrate to RBC receptors during matura-

tion. RBCs of type A contain an enzyme that adds N-acetylgalac-

tosamine to the receptor; RBCs of type B have an enzyme that adds

D-galactose; RBCs of type AB contain both enzymes that add both

carbohydrates; and RBCs of type O lack the genes and enzymes to

add a terminal molecule.

ANTIBODIES AGAINST A AND B ANTIGENS

Although an individual does not normally produce antibodies in

response to his or her own RBC antigens, the serum can contain

antibodies that react with blood of another antigenic type, even

though contact with this other blood type has

never occurred.

These performed antibodies account for the immediate and in-

tense quality of transfusion reactions. As a rule, type A blood

contains antibodies (anti-b) that react against the B antigens on

type B and AB red blood cells. Type B blood contains antibodies

(anti-a) that react with A antigen on type A and AB red blood

cells. Type O blood contains antibodies against both A and B anti-

gens. Type AB blood does not contain antibodies against either

A or B antigens

1

(table 17.3). What is the source of these anti-a

and anti-b antibodies? It appears that they develop in early in-

fancy because of exposure to certain heterophile antigens that are

widely distributed in nature. These antigens are surface molecules

on bacteria and plant cells that mimic the structure of A and B

antigens. Exposure to these sources stimulates the production of

corresponding antibodies.

2

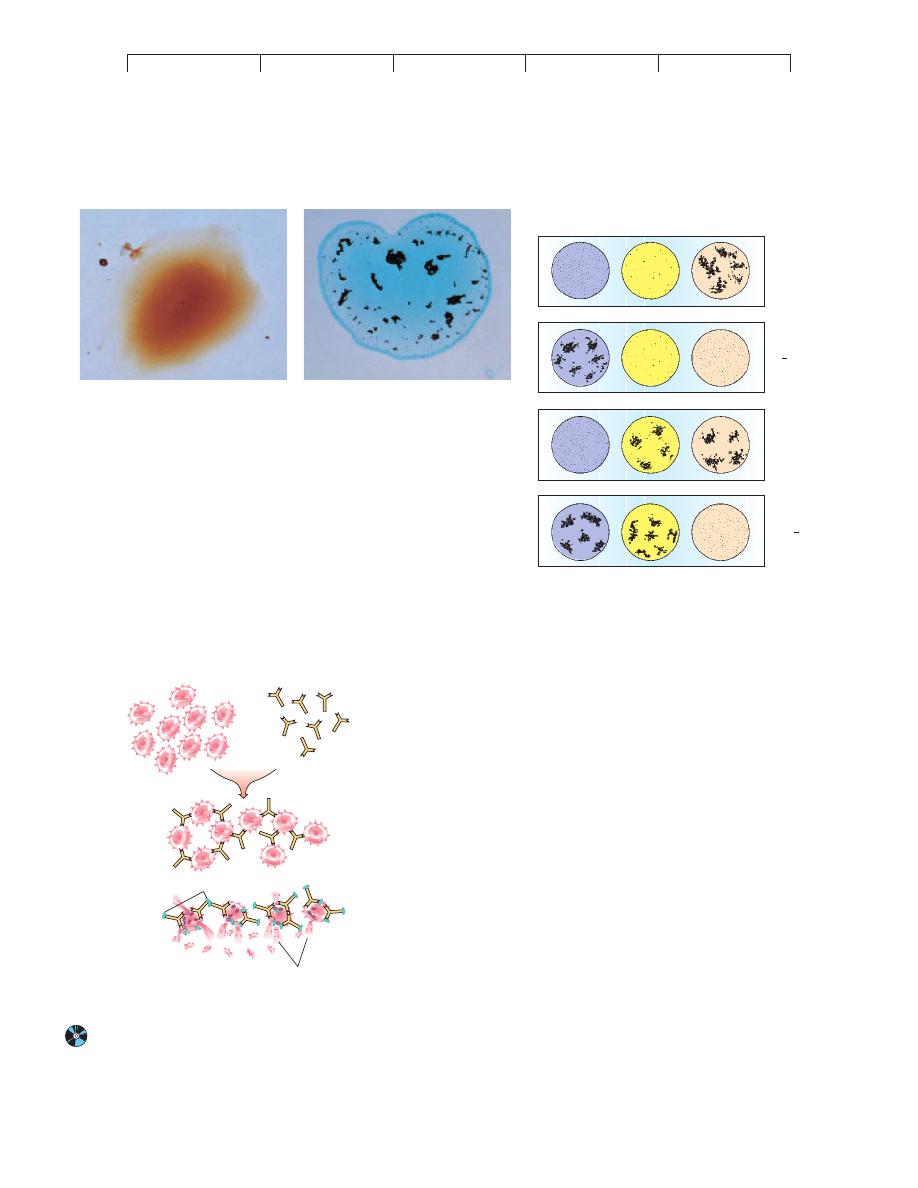

Clinical Concerns in Transfusions

The presence of ABO antigens and a, b antibodies underlie several

clinical concerns in giving blood transfusions. First, the individual

blood types of donor and recipient must be determined. By use of a

standard technique, drops of blood are mixed with antisera that

contain antibodies against the A and B antigens and are then ob-

served for the evidence of agglutination (figure 17.10).

Knowing the blood types involved makes it possible to deter-

mine which transfusions are safe to do. The general rule of compat-

ibility is that the RBC antigens of the donor must not be aggluti-

nated by antibodies in the recipient’s blood (figure 17.11). The ideal

practice is to transfuse blood that is a perfect match (A to A, B to

B). But even in this event, blood samples must be cross-matched

before the transfusion because other blood group incompatibilities

can exist. This test involves mixing the blood of the donor with the

serum of the recipient to check for agglutination.

Under certain circumstances (emergencies, the battlefield),

the concept of universal transfusions can be used. To appreciate

how this works, we must apply the rule stated in the previous para-

graph. Type O blood lacks A and B antigens and will not be agglu-

tinated by other blood types, so it could theoretically be used in any

transfusion. Hence, a person with this blood type is called a

univer-

sal donor. Because type AB blood lacks agglutinating antibodies,

an individual with this blood could conceivably receive any type of

blood. Type AB persons are consequently called

universal recipi-

ents. Although both types of transfusions involve antigen-antibody

incompatibilities, these are of less concern because of the dilution

of the donor’s blood in the body of the recipient. Additional RBC

markers that can be significant in transfusions are the Rh, MN, and

Kell antigens (see next sections).

Transfusion of the wrong blood type causes various degrees

of adverse reaction. The severest reaction is massive hemolysis

when the donated red blood cells react with recipient antibody

and trigger the complement cascade (figure 17.11). The resultant

destruction of red cells leads to systemic shock and kidney failure

brought on by the blockage of glomeruli (blood-filtering appara-

tus) by cell debris. Death is a common outcome. Other reactions

caused by RBC destruction are fever, anemia, and jaundice. A

transfusion reaction is managed by immediately halting the trans-

fusion, administering drugs to remove hemoglobin from the

blood, and beginning another transfusion with red blood cells of

the correct type.

RBC

RBC

RBC

RBC

B

A

A

B

Terminal sugar

Common receptor

Type A

Type B

Type AB

Type O

FIGURE 17.9

The genetic/molecular basis for the A and B antigens (receptors) on

red blood cells.

In general, persons with blood types A, B, and AB

inherit a gene for the enzyme that adds a certain terminal sugar to the

basic RBC receptor. Type O persons do not have such an enzyme and

lack the terminal sugar.

1. Why would this be true? The answer lies in the first sentence of the paragraph.

2. Evidence comes from germ-free chickens, which do not have antibodies against the

antigens of blood types, whereas normal chickens possess these antibodies.

Talaro−Talaro: Foundations

in Microbiology, Fourth

Edition

17. Disorders in Immunity

Text

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2002

510

CHAPTER 17 Disorders in Immunity

THE RH FACTOR AND ITS

CLINICAL IMPORTANCE

Another RBC antigen of major clinical concern is the

Rh factor (or

D antigen). This factor was first discovered in experiments explor-

ing the genetic relationships among animals. Rabbits inoculated

with the RBCs of rhesus monkeys produced an antibody that also

reacted with human RBCs. Further tests showed that this monkey

antigen (termed Rh for rhesus) was present in about 85% of humans

and absent in the other 15%. The details of Rh inheritance are more

complicated than those of ABO, but in simplest terms, a person’s

Rh type results from a combination of two possible alleles—a

dominant one that codes for the factor and a recessive one that does

not. A person inheriting at least one Rh gene will be Rh

"

; only

those persons inheriting two recessive genes are Rh

#

. This factor is

denoted by a symbol above the blood type, as in O

"

or AB

#

(see

figure 17.10

c). However, unlike the ABO antigens, exposure to nor-

mal flora does not sensitize Rh

#

persons to the Rh factor. The only

ways one can develop antibodies against this factor are through pla-

cental sensitization or transfusion.

(a)

(b)

Type A Donor

Type B Recipient

Complement

Hemoglobin

being released

FIGURE 17.10

Interpretation of blood typing.

In this test, a drop of blood is mixed with a specially

prepared antiserum known to contain antibodies against the A, B, or Rh antigens. (a) If

that particular antigen is not present, the red blood cells in that droplet do not agglutinate

and form an even suspension. (b) If that antigen is present, agglutination occurs and the

RBCs form visible clumps. (c) Several patterns and their interpretations. Anti-a, anti-b,

and anti-Rh are shorthand for the antiserum applied to the drops. (In general, O

"

is the

most common blood type, and AB

#

is the rarest.)

FIGURE 17.11

Microscopic view of a transfusion reaction.

(a) Incompatible

blood. The red blood cells of the type A donor contain antigen A,

while the serum of the type B recipient contains anti-a antibodies that can

agglutinate donor cells. (b) Agglutination particles can block the

circulation in vital organs. (c) Activation of the complement by antibody on

the RBCs can cause hemolysis and anemia. This sort of incorrect

transfusion is very rare because of the great care taken by blood banks to

ensure a correct match.

(a)

(b)

(c)

AB

Blood

type

O+

Anti-Rh

Anti-b

Anti-a

A

B+

(c)

Talaro−Talaro: Foundations

in Microbiology, Fourth

Edition

17. Disorders in Immunity

Text

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2002

Type II Hypersensitivities: Reactions That Lyse Foreign Cells

511

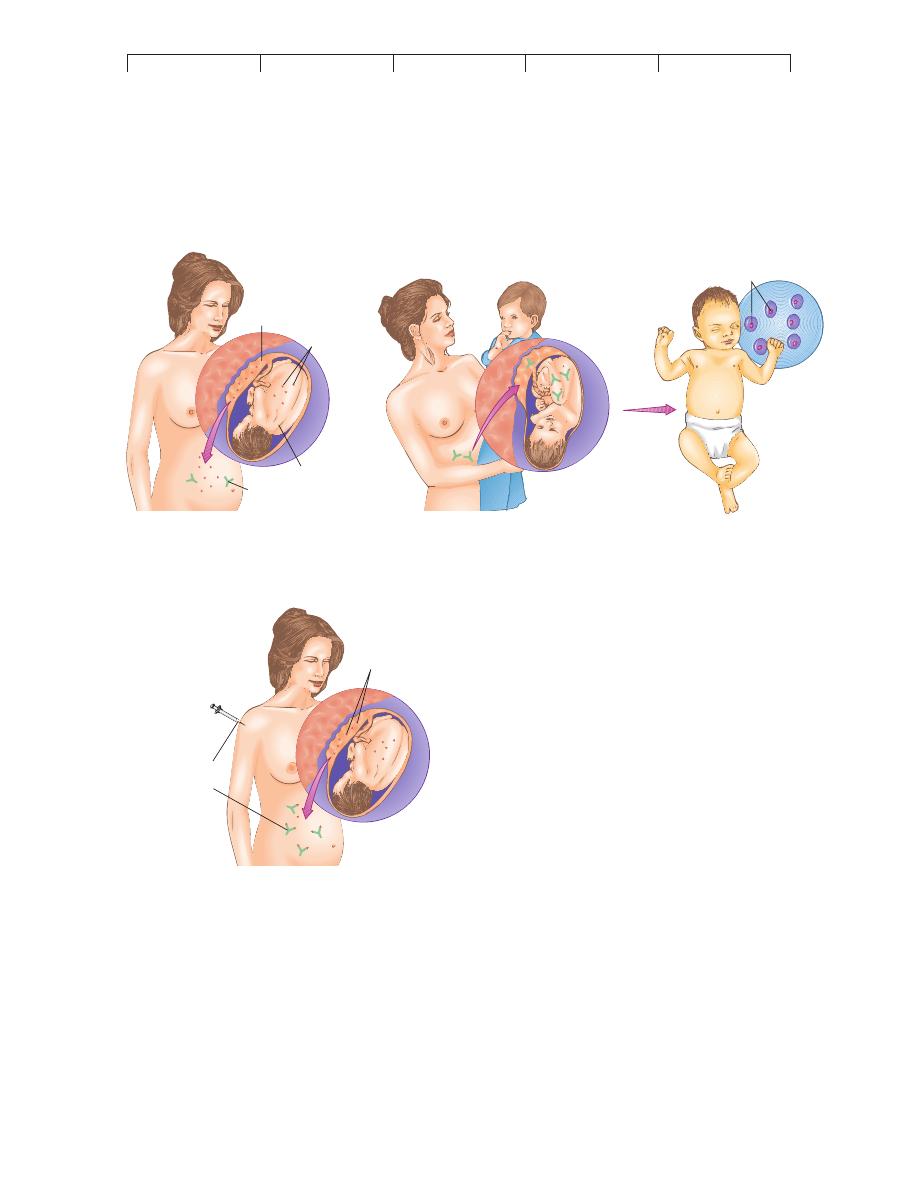

Hemolytic Disease of the Newborn

and Rh Incompatibility

The potential for placental sensitization occurs when a mother is

Rh

#

and her unborn child is Rh

"

. The obvious intimacy between

mother and fetus makes it possible for fetal RBCs to leak into the

mother’s circulation during childbirth, when the detachment of the

placenta creates avenues for fetal blood to enter the maternal circu-

lation. The mother’s immune system detects the foreign Rh factors

on the fetal RBCs and is sensitized to them by producing antibod-

ies and memory B cells. The first Rh

"

child is usually not affected

because the process begins so late in pregnancy that the child is

born before maternal sensitization is completed. However, the

mother’s immune system has been strongly primed for a second

contact with this factor in a subsequent pregnancy (figure 17.12

a).

In the next pregnancy with an Rh

"

fetus, fetal blood cells es-

cape into the maternal circulation late in pregnancy and elicit a

memory response. The fetus is at risk when the maternal anti-Rh

antibodies cross the placenta into the fetal circulation, where they

affix to fetal RBCs and cause complement-mediated lysis. The out-

come is a potentially fatal

hemolytic disease of the newborn

(HDN) called erythroblastosis fetalis (eh-rith

-roh-blas-toh-sis

fee-tal

-is). This term is derived from the presence of immature nu-

cleated RBCs called erythroblasts in the blood. They are released

into the infant’s circulation to compensate for the massive destruc-

tion of RBCs by maternal antibodies. Additional symptoms are se-

vere anemia, jaundice, and enlarged spleen and liver.

Maternal-fetal incompatibilities are also possible in the ABO

blood group, but adverse reactions occur less frequently than with

First Rh

+

fetus

Anti-Rh antibody

Rh

+

fetus

Rh factor

on RBCs

Placenta breaks

away

Rh

–

mother

Erythroblasts

in blood

Second Rh

+

fetus

Late in second pregnancy

of Rh

+

child

First Rh

+

fetus

Anti-Rh

antibodies

(RhoGAM)

Rh

+

RBCs

Rh

–

mother

(a) The development and aftermath of Rh sensitization.

(b) Prevention of erythroblastosis fetalis with anti-Rh immune globulin (RhoGAM)

FIGURE 17.12

Development and control of Rh incompatibility.

(a) Initial

sensitization of the maternal immune system to fetal Rh factor occurs

when fetal cells leak into the mother’s circulation late in pregnancy, or

during delivery, when the placenta tears away. The child will escape

hemolytic disease in most instances, but the mother, now sensitized,

will be capable of an immediate reaction to a second Rh

"

fetus and its

Rh-factor antigen. At that time, the mother’s anti-Rh antibodies pass

into the fetal circulation and elicit severe hemolysis in the fetus and

neonate. (b) Prevention of erythroblastosis fetalis with anti-Rh immune

globulin (RhoGAM). Injecting a mother who is at risk with RhoGAM

during her first Rh

"

pregnancy helps to inactivate and remove the fetal

Rh-positive cells before her immune system can react and develop

sensitivity.

Talaro−Talaro: Foundations

in Microbiology, Fourth

Edition

17. Disorders in Immunity

Text

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2002

512

CHAPTER 17 Disorders in Immunity

Rh sensitization because the antibodies to these blood group anti-

gens are IgM rather than IgG and are unable to cross the placenta in

large numbers. In fact, the maternal-fetal relationship is a fascinat-

ing instance of foreign tissue not being rejected, despite the exten-

sive potential for contact (Medical Microfile 17.2).

Preventing Hemolytic Disease of the Newborn

Once sensitization of the mother to Rh factor has occurred, all other

Rh

"

fetuses will be at risk for hemolytic disease of the newborn.

Prevention requires a careful family history of an Rh

#

pregnant

woman. It can predict the likelihood that she is already sensitized or

is carrying an Rh

"

fetus. It must take into account other children

she has had, their Rh types, and the Rh status of the father. If the fa-

ther is also Rh

#

, the child will be Rh

#

and free of risk, but if the fa-

ther is Rh

"

, the probability that the child will be Rh

"

is 50% or

100%, depending on the exact genetic makeup of the father. If there

is any possibility that the fetus is Rh

"

, the mother must be pas-

sively immunized with antiserum containing antibodies against the

Rh factor (

Rh

o

[

D] immune globulin, or RhoGAM*). This anti-

serum, injected at 28 to 32 weeks and again immediately after de-

livery, reacts with any fetal RBCs that have escaped into the mater-

nal circulation, thereby preventing the sensitization of the mother’s

immune system to Rh factor (figure 17.12

b). Anti-Rh antibody

must be given with each pregnancy that involves an Rh

"

fetus. It is

ineffective if the mother has already been sensitized by a prior Rh

"

fetus or an incorrect blood transfusion, which can be determined by

a serological test. As in ABO blood types, the Rh factor should be

matched for a transfusion, although it is acceptable to transfuse

Rh

#

blood if the Rh type is not known.

OTHER RBC ANTIGENS

Although the ABO and Rh systems are of greatest medical signifi-

cance, about 20 other red blood cell antigen groups have been

discovered. Examples are the

MN, Ss, Kell, and P blood groups.

Because of incompatibilities that these blood groups present, trans-

fused blood is screened to prevent possible cross-reactions. The

study of these blood antigens (as well as ABO and Rh) has given

rise to other useful applications. For example, they can be useful in

forensic medicine (crime detection), studying ethnic ancestry, and

tracing prehistoric migrations in anthropology. Many blood cell

antigens are remarkably hardy and can be detected in dried blood

stains, semen, and saliva. Even the 2,000-year-old mummy of King

Tutankhamen has been typed A

2

MN!

MEDICAL MICROFILE

17.2

Why Doesn’t a Mother Reject Her Fetus?

what ways do fetuses avoid the surveillance of the mother’s immune sys-

tem? The answer appears to lie in the placenta and embryonic tissues.

The fetal components that contribute to these tissues are not strongly

antigenic, and they form a barrier that keeps the fetus isolated in its own

antigen-free environment. The placenta is surrounded by a dense, many-

layered envelope that prevents the passage of maternal cells, and it ac-

tively absorbs, removes, and inactivates circulating antigens.

Think of it: Even though mother and child are genetically related, the fa-

ther’s genetic contribution guarantees that the fetus will contain mole-

cules that are antigenic to the mother. In fact, with the recent practice of

implanting one woman with the fertilized egg of another woman, the sur-

rogate mother is carrying a fetus that has no genetic relationship to her.

Yet, even with this essentially foreign body inside the mother, dangerous

immunologic reactions such as Rh incompatibility are rather rare. In

*

RhoGAM

Immunoglobulin fraction of human anti-Rh serum, prepared from pooled

human sera.

Type II hypersensitivity reactions occur when preformed antibodies

react with foreign cell-bound antigens. The most common type II

reactions occur when transfused blood is mismatched to the recipient’s

ABO type. IgG or IgM antibodies attach to the foreign cells, resulting

in complement fixation. The resultant formation of membrane attack

complexes lyses the donor cells.

Type II hypersensitivities are stimulated by antibodies formed against red

blood cell (RBC) antigens or against other cell-bound antigens

following prior exposure.

Complement, IgG, and IgM antibodies are the primary mediators of

type II hypersensitivities.

The concepts of universal donor (type O) and universal recipient

(type AB) apply only under emergency circumstances. Cross-matching

donor and recipient blood is necessary to determine which

transfusions are safe to perform.

Type II hypersensitivities can also occur when Rh

#

mothers are sensitized

to Rh

"

RBCs of their unborn babies and the mother’s anti-Rh antibodies

cross the placenta, causing hemolysis of the newborn’s RBCs. This is

called hemolytic disease of the newborn, or erythroblastosis fetalis.

CHAPTER CHECKPOINTS

Type III Hypersensitivities: Immune

Complex Reactions

Type III hypersensitivity involves the reaction of soluble antigen

with antibody and the deposition of the resulting complexes in base-

ment membranes of epithelial tissue. It is similar to type II, because

it involves the production of IgG and IgM antibodies after repeated

exposure to antigens and the activation of complement. Type III

differs from type II because its antigens are not attached to the sur-

face of a cell. The interaction of these antigens with antibodies