Talaro−Talaro: Foundations

in Microbiology, Fourth

Edition

17. Disorders in Immunity

Text

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2002

512

CHAPTER 17 Disorders in Immunity

Rh sensitization because the antibodies to these blood group anti-

gens are IgM rather than IgG and are unable to cross the placenta in

large numbers. In fact, the maternal-fetal relationship is a fascinat-

ing instance of foreign tissue not being rejected, despite the exten-

sive potential for contact (Medical Microfile 17.2).

Preventing Hemolytic Disease of the Newborn

Once sensitization of the mother to Rh factor has occurred, all other

Rh

"

fetuses will be at risk for hemolytic disease of the newborn.

Prevention requires a careful family history of an Rh

#

pregnant

woman. It can predict the likelihood that she is already sensitized or

is carrying an Rh

"

fetus. It must take into account other children

she has had, their Rh types, and the Rh status of the father. If the fa-

ther is also Rh

#

, the child will be Rh

#

and free of risk, but if the fa-

ther is Rh

"

, the probability that the child will be Rh

"

is 50% or

100%, depending on the exact genetic makeup of the father. If there

is any possibility that the fetus is Rh

"

, the mother must be pas-

sively immunized with antiserum containing antibodies against the

Rh factor (Rh

o

[D] immune globulin, or RhoGAM*). This anti-

serum, injected at 28 to 32 weeks and again immediately after de-

livery, reacts with any fetal RBCs that have escaped into the mater-

nal circulation, thereby preventing the sensitization of the mother’s

immune system to Rh factor (figure 17.12b). Anti-Rh antibody

must be given with each pregnancy that involves an Rh

"

fetus. It is

ineffective if the mother has already been sensitized by a prior Rh

"

fetus or an incorrect blood transfusion, which can be determined by

a serological test. As in ABO blood types, the Rh factor should be

matched for a transfusion, although it is acceptable to transfuse

Rh

#

blood if the Rh type is not known.

OTHER RBC ANTIGENS

Although the ABO and Rh systems are of greatest medical signifi-

cance, about 20 other red blood cell antigen groups have been

discovered. Examples are the MN, Ss, Kell, and P blood groups.

Because of incompatibilities that these blood groups present, trans-

fused blood is screened to prevent possible cross-reactions. The

study of these blood antigens (as well as ABO and Rh) has given

rise to other useful applications. For example, they can be useful in

forensic medicine (crime detection), studying ethnic ancestry, and

tracing prehistoric migrations in anthropology. Many blood cell

antigens are remarkably hardy and can be detected in dried blood

stains, semen, and saliva. Even the 2,000-year-old mummy of King

Tutankhamen has been typed A

2

MN!

MEDICAL MICROFILE

17.2

Why Doesn’t a Mother Reject Her Fetus?

what ways do fetuses avoid the surveillance of the mother’s immune sys-

tem? The answer appears to lie in the placenta and embryonic tissues.

The fetal components that contribute to these tissues are not strongly

antigenic, and they form a barrier that keeps the fetus isolated in its own

antigen-free environment. The placenta is surrounded by a dense, many-

layered envelope that prevents the passage of maternal cells, and it ac-

tively absorbs, removes, and inactivates circulating antigens.

Think of it: Even though mother and child are genetically related, the fa-

ther’s genetic contribution guarantees that the fetus will contain mole-

cules that are antigenic to the mother. In fact, with the recent practice of

implanting one woman with the fertilized egg of another woman, the sur-

rogate mother is carrying a fetus that has no genetic relationship to her.

Yet, even with this essentially foreign body inside the mother, dangerous

immunologic reactions such as Rh incompatibility are rather rare. In

*

RhoGAM

Immunoglobulin fraction of human anti-Rh serum, prepared from pooled

human sera.

Type II hypersensitivity reactions occur when preformed antibodies

react with foreign cell-bound antigens. The most common type II

reactions occur when transfused blood is mismatched to the recipient’s

ABO type. IgG or IgM antibodies attach to the foreign cells, resulting

in complement fixation. The resultant formation of membrane attack

complexes lyses the donor cells.

Type II hypersensitivities are stimulated by antibodies formed against red

blood cell (RBC) antigens or against other cell-bound antigens

following prior exposure.

Complement, IgG, and IgM antibodies are the primary mediators of

type II hypersensitivities.

The concepts of universal donor (type O) and universal recipient

(type AB) apply only under emergency circumstances. Cross-matching

donor and recipient blood is necessary to determine which

transfusions are safe to perform.

Type II hypersensitivities can also occur when Rh

#

mothers are sensitized

to Rh

"

RBCs of their unborn babies and the mother’s anti-Rh antibodies

cross the placenta, causing hemolysis of the newborn’s RBCs. This is

called hemolytic disease of the newborn, or erythroblastosis fetalis.

CHAPTER CHECKPOINTS

Type III Hypersensitivities: Immune

Complex Reactions

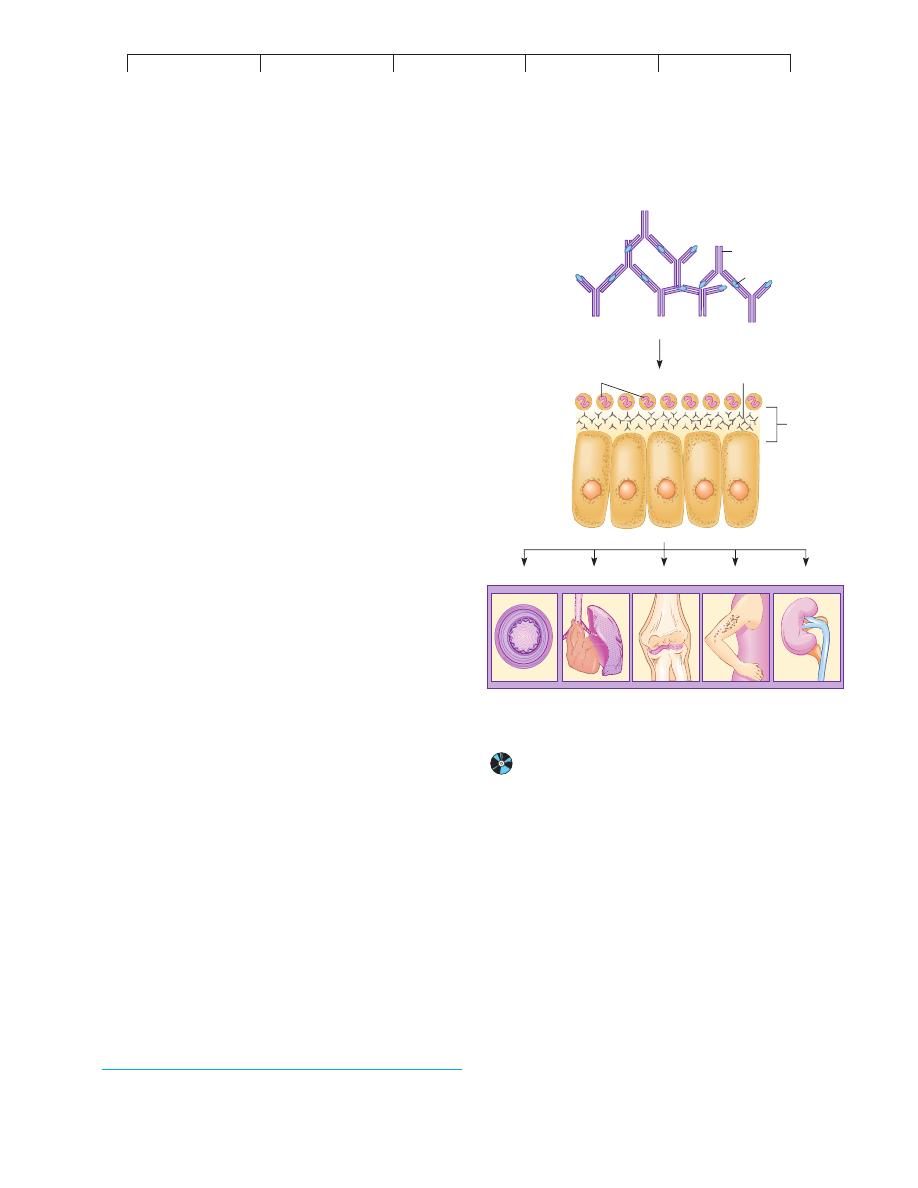

Type III hypersensitivity involves the reaction of soluble antigen

with antibody and the deposition of the resulting complexes in base-

ment membranes of epithelial tissue. It is similar to type II, because

it involves the production of IgG and IgM antibodies after repeated

exposure to antigens and the activation of complement. Type III

differs from type II because its antigens are not attached to the sur-

face of a cell. The interaction of these antigens with antibodies

Talaro−Talaro: Foundations

in Microbiology, Fourth

Edition

17. Disorders in Immunity

Text

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2002

Type III Hypersensitivities: Immune Complex Reactions

513

produces free-floating complexes that can be deposited in the tis-

sues, causing an

immune complex reaction or disease. This cate-

gory includes therapy-related disorders (serum sickness and the

Arthus reaction) and a number of autoimmune diseases (such as

glomerulonephritis and lupus erythematosus).

MECHANISMS OF IMMUNE COMPLEX DISEASE

After initial exposure to a profuse amount of antigen, the immune

system produces large quantities of antibodies that circulate in the

fluid compartments. When this antigen enters the system a second

time, it reacts with the antibodies to form antigen-antibody com-

plexes (figure 17.13). These complexes summon various inflamma-

tory components such as complement and neutrophils, which

would ordinarily eliminate Ag-Ab complexes as part of the normal

immune response. In an immune complex disease, however, these

complexes are so abundant that they deposit in the basement mem-

branes* of epithelial tissues and become inaccessible. In response

to these events, neutrophils release lysosomal granules that digest

tissues and cause a destructive inflammatory condition. The symp-

toms of type III hypersensitivities are due in great measure to this

pathologic state.

TYPES OF IMMUNE COMPLEX DISEASE

During the early tests of immunotherapy using animals, hyper-

sensitivity reactions to serum and vaccines were common. In ad-

dition to anaphylaxis, two syndromes, the

Arthus reaction

3

and

serum sickness, were identified. These syndromes are associated

with certain types of passive immunization (especially with ani-

mal serum).

Serum sickness and the Arthus reaction are like anaphylaxis

in requiring sensitization and preformed antibodies. Characteristics

that set them apart are: (1) They depend upon IgG, IgM, or IgA

(precipitating antibodies) rather than IgE; (2) they require large

doses of antigen (not a miniscule dose as in anaphylaxis); and

(3) they have delayed symptoms (a few hours to days). The Arthus

reaction and serum sickness differ from each other in some impor-

tant ways. The Arthus reaction is a localized dermal injury due to

inflamed blood vessels in the vicinity of any injected antigen.

Serum sickness is a systemic injury initiated by antigen-antibody

complexes that circulate in the blood and settle into membranes at

various sites.

The Arthus Reaction

The Arthus reaction is usually an acute response to a second injec-

tion of vaccines (boosters) or drugs at the same site as the first in-

jection. In a few hours, the area becomes red, hot to the touch,

swollen, and very painful. These symptoms are mainly due to the

destruction of tissues in and around the blood vessels and the re-

lease of histamine from mast cells and basophils. Although the re-

action is usually self-limiting and rapidly cleared, intravascular

blood clotting can occasionally cause necrosis and loss of tissue.

Serum Sickness

Serum sickness was named for a condition that appeared in soldiers

after repeated injections of horse serum to treat tetanus. It can also

be caused by injections of animal hormones and drugs. The im-

mune complexes enter the circulation, are carried throughout the

body, and are eventually deposited in blood vessels of the kidney,

heart, skin, and joints (figure 17.13). The condition can become

chronic, causing symptoms such as enlarged lymph nodes, rashes,

painful joints, swelling, fever, and renal dysfunction.

AN INAPPROPRIATE RESPONSE

AGAINST SELF, OR AUTOIMMUNITY

The immune diseases we have covered so far are all caused by

foreign antigens. In the case of

autoimmunity, an individual actu-

ally develops hypersensitivity to himself. This pathologic process

accounts for

autoimmune diseases, in which autoantibodies and,

in certain cases, T cells mount an abnormal attack against self anti-

gens. The scope of autoimmune diseases is extremely varied. In

Ab

Ag

Immune complexes

Lodging of complexes

in basement membrane

Ag/Ab complexes

Neutrophils

Basement

membrane

Epithelial

tissue

Blood vessels Heart/Lungs

Joints

Skin

Kidney

Major organs that can be targets

of immune complex deposition

FIGURE 17.13

The background of immune complex disease.

In general,

circulating immune complexes become lodged in the basement

membrane of the epithelia and cause vascular damage and organ

malfunction.

3. Named after Maurice Arthus, the physiologist who first identified this localized

inflammatory response.

*

Basement membranes

are basal partitions of epithelia that normally filter out

circulating antigen-antibody complexes.

Talaro−Talaro: Foundations

in Microbiology, Fourth

Edition

17. Disorders in Immunity

Text

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2002

514

CHAPTER 17 Disorders in Immunity

general, they can be differentiated as systemic, involving several

major organs, or organ-specific, involving only one organ or tissue.

They usually fall into the categories of type II or type III hypersen-

sitivity, depending upon how the autoantibodies bring about injury.

Some major autoimmune diseases, their targets, and basic pathol-

ogy are presented in table 17.4.

Genetic and Gender Correlation

in Autoimmune Disease

In most cases, the precipitating cause of autoimmune disease re-

mains obscure, but we do know that susceptibility is determined by

genetics and influenced by gender. Cases cluster in families, and

even unaffected members tend to develop the autoantibodies for

that disease. More direct evidence comes from studies of the major

histocompatibility gene complex. Particular genes in the class I and

II major histocompatibility complex (see figure 15.3) coincide with

certain autoimmune diseases. For example, autoimmune joint dis-

eases such as rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis are

more common in persons with the B-27 HLA type; systemic lupus

erythematosus, Graves disease, and myasthenia gravis are associ-

ated with the B-8 HLA antigen. Why autoimmune diseases (except

ankylosing spondylitis) afflict more females than males also re-

mains a mystery. Females are more susceptible during childbearing

years than before puberty or after menopause, suggesting a possible

hormonal relationship.

The Origins of Autoimmune Disease

Very low titers of autoantibodies in otherwise healthy individuals

suggest some normal function for them. A moderate, regulated

amount of autoimmunity is probably required to dispose of old

cells and cellular debris. Disease apparently arises when this regu-

latory or recognition apparatus goes awry. Attempts to explain the

origin of autoimmunity include the following theories.

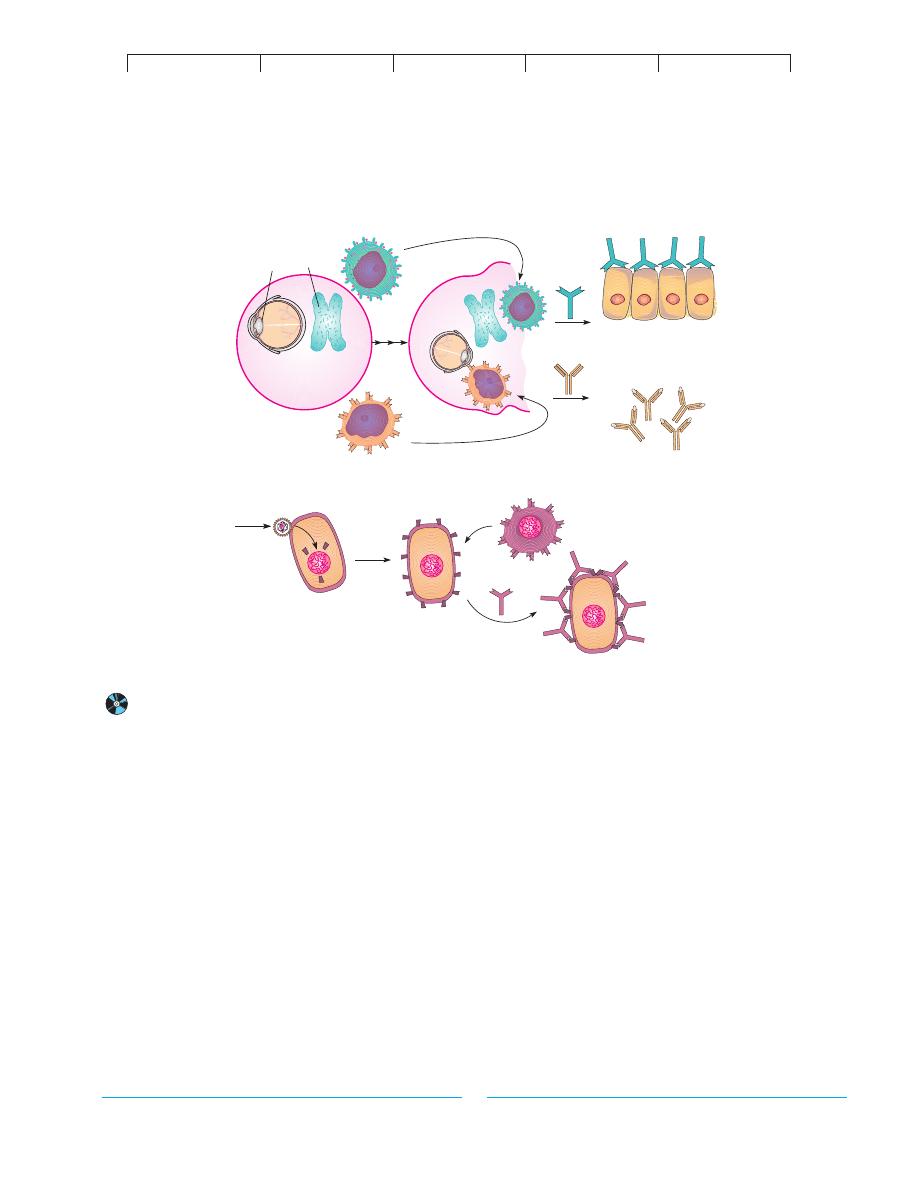

The sequestered antigen theory explains that during embry-

onic growth, some tissues are immunologically privileged; that is,

they are sequestered behind anatomical barriers and cannot be

scanned by the immune system (figure 17.14a). Examples of

these sites are regions of the central nervous system, which are

shielded by the meninges and blood-brain barrier; the lens of the

eye, which is enclosed by a thick sheath; and antigens in the thy-

roid and testes, which are sequestered behind an epithelial barrier.

Eventually the antigen becomes exposed by means of infection,

trauma, or deterioration, and is perceived by the immune system

as a foreign substance.

According to the clonal selection theory, the immune system

of a fetus develops tolerance by eradicating all self-reacting lym-

phocyte clones, called forbidden clones, while retaining only those

clones that react to foreign antigens. Some of these clones may sur-

vive, and since they have not been subjected to this tolerance

process, they can attack tissues with self antigens.

The theory of immune deficiency proposes that mutations in

the receptor genes of some lymphocytes render them reactive to

self or that a general breakdown in the normal T-suppressor func-

tion sets the scene for inappropriate immune responses.

Some autoimmune diseases appear to be caused by molecu-

lar mimicry, in which microbial antigens bear molecular determi-

nants similar to normal human cells. An infection could cause for-

mation of antibodies that can cross-react with tissues. This is one

purported explanation for the pathology of rheumatic fever. Au-

toimmune disorders such as type I diabetes and multiple sclerosis

TABLE 17.4

Selected Autoimmune Diseases

Type of

Disease

Target

Hypersensitivity

Characteristics

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Systemic

III

Inflammation of many organs; antibodies against red and

(SLE)

white blood cells, platelets, clotting factors, nucleus

Rheumatoid arthritis and

Systemic

III

Vasculitis; frequent target is joint lining; antibodies against

ankylosing spondylitis

other antibodies (rheumatoid factor)

Scleroderma

Systemic

II

Excess collagen deposition in organs; antibodies formed

against many intracellular organelles

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis

Thyroid

II

Destruction of the thyroid follicles

Graves disease

Thyroid

II

Antibodies against thyroid-stimulating hormone receptors

Pernicious anemia

Stomach lining

II

Antibodies against receptors prevent transport of vitamin B

12

Myasthenia gravis

Muscle

II

Antibodies against the acetylcholine receptors on the

nerve-muscle junction alter function

Type I diabetes

Pancreas

II

Antibodies stimulate destruction of insulin-secreting cells

Type II diabetes

Insulin receptor

II

Antibodies block attachment of insulin

Multiple sclerosis

Myelin

II

T cells and antibodies sensitized to myelin sheath destroy

neurons

Goodpasture syndrome

Kidney

II

Antibodies to basement membrane of the glomerulus damage

(glomerulonephritis)

kidneys

Rheumatic fever

Heart

II

Antibodies to group A Streptococcus cross-react with heart

tissue

Talaro−Talaro: Foundations

in Microbiology, Fourth

Edition

17. Disorders in Immunity

Text

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2002

Type III Hypersensitivities: Immune Complex Reactions

515

are likely triggered by viral infection. Viruses can noticeably alter

cell receptors, thereby causing immune cells to attack the tissues

bearing viral receptors (figure 17.14b).

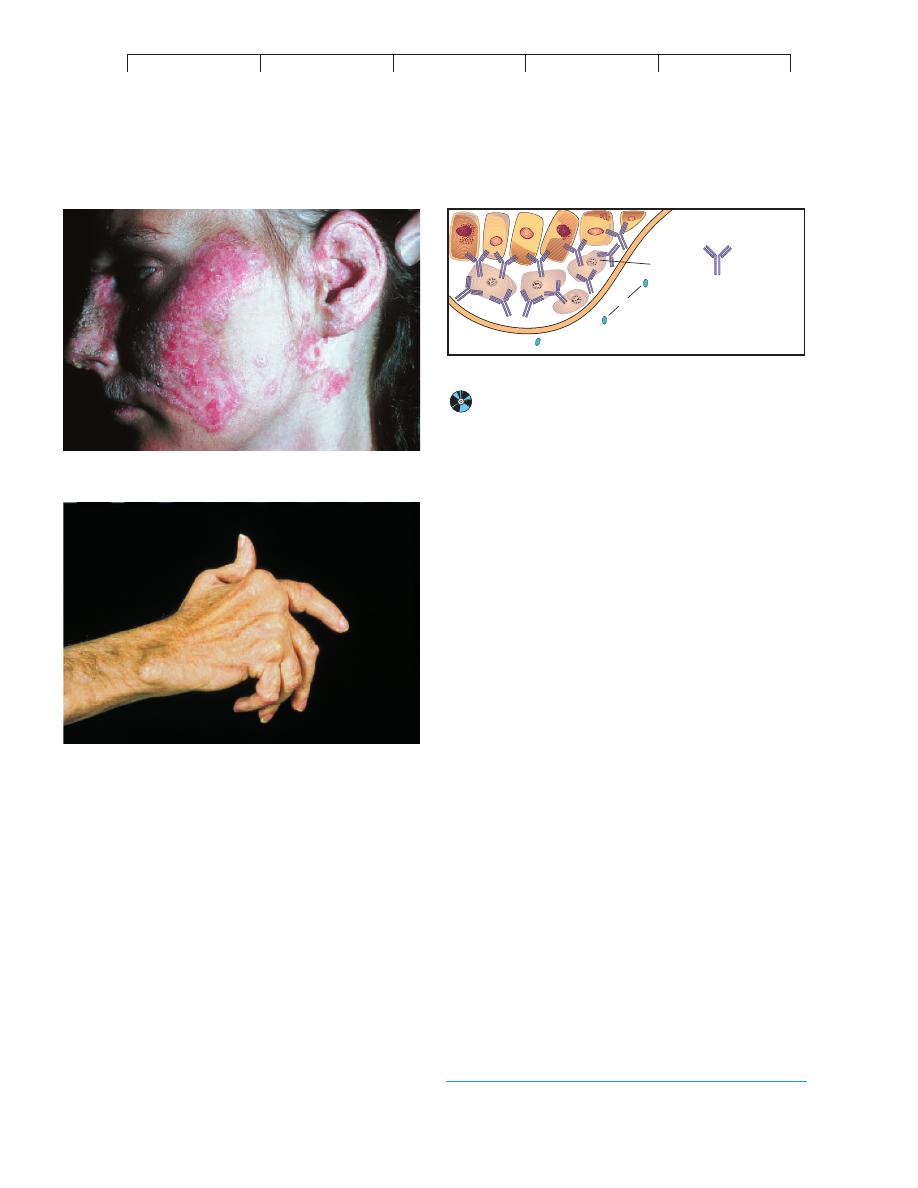

Examples of Autoimmune Disease

Systemic Autoimmunities

One of the severest chronic autoim-

mune diseases is

systemic lupus erythematosus* (SLE, or lupus).

This name originated from the characteristic rash that spreads

across the nose and cheeks in a pattern suggesting the appearance

of a wolf (figure 17.15a). Although the manifestations of the dis-

ease vary considerably, all patients produce autoantibodies against

a great variety of organs and tissues. The organs most involved are

the kidneys, bone marrow, skin, nervous system, joints, muscles,

heart, and GI tract. Antibodies to intracellular materials such as the

nucleoprotein of the nucleus and mitochondria are also common.

In SLE, autoantibody-autoantigen complexes appear to be

deposited in the basement membranes of various organs. Kidney

failure, blood abnormalities, lung inflammation, myocarditis, and

skin lesions are the predominant symptoms. One form of chronic

lupus (called discoid) is influenced by exposure to the sun and pri-

marily afflicts the skin. The etiology of lupus is still a puzzle. It is

not known how such a generalized loss of self-tolerance arises,

though viral infection or loss of T-cell suppressor function are sus-

pected. The fact that women of childbearing years account for 90%

of cases indicates that hormones may be involved. The diagnosis of

SLE can usually be made with blood tests. Antibodies against the

nucleus (ANA) and various tissues (detected by indirect fluorescent

antibody or radioimmune assay techniques) are common, and a

positive test for the lupus factor (an antinuclear factor) is also very

indicative of the disease.

Rheumatoid arthritis,* another systemic autoimmune dis-

ease, incurs progressive, debilitating damage to the joints. In some

patients, the lung, eye, skin, and nervous system are also involved.

In the joint form of the disease, autoantibodies form immune com-

plexes that bind to the synovial membrane of the joints and activate

phagocytes and stimulate release of cytokines. Chronic inflamma-

tion leads to scar tissue and joint destruction. The joints in the

hands and feet are affected first, followed by the knee and hip joints

(figure 17.15b). The precipitating cause in rheumatoid arthritis is

B cell

Sequestered tissues

with hidden

antigen

B cell

Autoantibodies

Thyroid cells

Lens protein

Viral infection

of cell

Antibody

binds cells

bearing viral

receptor; cells

destroyed

B-cell clone

that recognizes

foreign receptor

Altered self antigens

Viral Infection Theory

A

ntib

ody formed

L

o

ss

o

f a

na

to

m

ica

l barr

ier

(b)

Sequestered Antigen Theory

(a)

Lens

Thyroid

gland

FIGURE 17.14

Possible explanations for autoimmunity.

(a) Self antigens are sequestered and later incorrectly identified as a foreign antigen by B lymphocytes.

(b) Self antigens are altered by viral infection, which causes an immune response against the perceived foreign antigens.

*

systemic lupus erythematosus

(sis-tem

-ik loo-pis air -uh-theem-uh-toh-sis)

L. lupus, wolf, and erythema, redness.

*

rheumatoid arthritis

(roo

-muh-toyd ar-thry-tis) Gr. rheuma, a moist discharge, and

arthron, joint.

Talaro−Talaro: Foundations

in Microbiology, Fourth

Edition

17. Disorders in Immunity

Text

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2002

516

CHAPTER 17 Disorders in Immunity

not known, though infectious agents such as Epstein-Barr virus

have been suspected. The most common feature of the disease is the

presence of an IgM antibody, called rheumatoid factor (RF), di-

rected against other antibodies. This does not cause the disease but

is used mainly in diagnosis. Some relief can be achieved with anti-

inflammatory agents, immunosuppressive drugs, and gold salt in-

jections in some individuals.

Autoimmunities of the Endocrine Glands

On occasion, the

thyroid gland is the target of autoimmunity. The underlying cause

of

Graves disease is the attachment of autoantibodies to receptors

on the follicle cells that secrete the hormone thyroxin. The abnor-

mal stimulation of these cells causes the overproduction of this hor-

mone and the symptoms of hyperthyroidism. In

Hashimoto

thyroiditis, both autoantibodies and T cells are reactive to the thy-

roid gland, but in this instance, they reduce the levels of thyroxin by

destroying follicle cells and by inactivating the hormone. As a re-

sult of these reactions, the patient suffers from hypothyroidism.

The pancreas and its hormone, insulin, are other autoim-

mune targets. Insulin, secreted by the beta cells in the pancreas,

regulates and is essential to the utilization of glucose by cells.

Diabetes mellitus is caused by a dysfunction in insulin production

or utilization (figure 17.16). Type I diabetes (also termed insulin-

dependent diabetes) is associated with autoantibodies and sensi-

tized T cells that damage the beta cells. A complex inflammatory

reaction leading to lysis of these cells greatly reduces the amount

of insulin secreted.

Neuromuscular Autoimmunities

Myasthenia gravis* is named

for the pronounced muscle weakness that is its principal symptom.

Although the disease afflicts all skeletal muscle, the first effects are

usually felt in the muscles of the eyes and throat. Eventually, it can

progress to complete loss of muscle function and death. The classic

syndrome is caused by autoantibodies binding to the receptors for

acetylcholine, a chemical required to transmit a nerve impulse

across the synaptic junction to a muscle (figure 17.17). The immune

attack so severely damages the muscle cell membrane that trans-

mission is blocked and paralysis ensues. Current treatment usually

includes immunosuppressive drugs and therapy to remove the au-

toantibodies from the circulation. Experimental therapy using im-

munotoxins to destroy lymphocytes that produce autoantibodies

shows some promise.

Multiple sclerosis* (MS) is a paralyzing neuromuscular dis-

ease associated with lesions in the insulating myelin sheath that

surrounds neurons in the white matter of the central nervous sys-

tem. The underlying pathology involves damage to the sheath by

(a)

(b)

FIGURE 17.15

Common autoimmune diseases.

(a) Systemic lupus erythematosus.

One symptom is a prominent rash across the bridge of the nose and on

the cheeks. These papules and blotches can also occur on the chest

and limbs. (b) Rheumatoid arthritis commonly targets the synovial

membrane of joints. Over time, chronic inflammation causes thickening

of this membrane, erosion of the articular cartilage, and fusion of the

joint. These effects severely limit motion and can eventually swell and

distort the joints.

Type I Diabetes

Damaged

islet cell

Autoantibody

specific for

islets

Insulin

FIGURE 17.16

The autoimmune component in diabetes mellitus, type I.

Autoantibodies produced against the beta cells of the islets of

Langerhans destroy the cells and greatly reduce insulin synthesis.

*

myasthenia gravis

(my

-us-thee-nee-uh grah-vis) Gr. myo, muscle, astheneia,

weakness, and gravida, heavy.

*

sclerosis

(skleh-roh

-sis) Gr. sklerosis, hardness.

Talaro−Talaro: Foundations

in Microbiology, Fourth

Edition

17. Disorders in Immunity

Text

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2002

Type IV Hypersensitivities: Cell-Mediated (Delayed) Reactions

517

both T cells and autoantibodies that severely compromises the ca-

pacity of neurons to send impulses. The principal motor and sen-

sory symptoms are muscular weakness and tremors, difficulties in

speech and vision, and some degree of paralysis. Most MS patients

first experience symptoms as young adults, and they tend to experi-

ence remissions (periods of relief) alternating with recurrences of

disease throughout their lives. Convincing evidence from studies of

the brain tissue of MS patients points to a strong connection

between the disease and infection with human herpesvirus 6 (see

chapter 24). The disease can be treated passively with monoclonal

antibodies that target T cells, and a vaccine containing the myelin

protein has shown beneficial effects. Immunosuppressants such as

cortisone and interferon B may also alleviate symptoms.

Type IV Hypersensitivities: Cell-Mediated

(Delayed) Reactions

The adverse immune responses we have covered so far are ex-

plained primarily by B-cell involvement and antibodies. But type

IV hypersensitivity involves primarily the T-cell branch of the im-

mune system. Type IV immune dysfunction has traditionally been

known as delayed hypersensitivity because the symptoms arise one

to several days following the second contact with an antigen. In

general, type IV diseases result when T cells respond to self tissues

or transplanted foreign cells. Examples of type IV hypersensitivity

include delayed allergic reactions to infectious agents, contact der-

matitis, and graft rejection.

DELAYED-TYPE HYPERSENSITIVITY

Infectious Allergy

A classic example of a delayed-type hypersensitivity occurs when a

person sensitized by tuberculosis infection is injected with an

extract (tuberculin) of the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

The so-called

tuberculin reaction is an acute skin inflammation at

the injection site appearing within 24 to 48 hours. So useful and di-

agnostic is this technique for detecting present or prior tuberculosis

that it is the chosen screening device (figure 17.18a). Other infec-

tions that use similar skin testing are leprosy, syphilis, histoplasmo-

sis, toxoplasmosis, and candidiasis. This form of hypersensitivity

arises from time-consuming cellular events involving the

T

D

class

of cells. After these cells receive processed microbial antigens from

macrophages, they release broad-spectrum cytokines that attract

inflammatory cells to the site—particularly mononuclear cells,

fibroblasts, and other lymphocytes. In a chronic infection (tertiary

syphilis, for example), extensive damage to organs can occur

through granuloma formation.

Contact Dermatitis

The most common delayed allergic reaction,

contact dermatitis, is

caused by exposure to resins in poison ivy or poison oak (Spotlight

on Microbiology 17.3), to simple haptens in household and per-

sonal articles ( jewelry, cosmetics, elasticized undergarments), and

to certain drugs. Like immediate atopic dermatitis, the reaction to

these allergens requires a sensitizing and a provocative dose. The

hypersensitivity reactions. Autoimmune T-cell responses are type IV

hypersensitivity reactions.

Susceptibility to autoimmune disease appears to be influenced by gender

and by genes in the MHC complex.

Autoimmune disease may be an excessive response of a normal immune

function, the appearance of sequestered antigens, “forbidden’’ clones

of lymphocytes that react to self antigens, or the result of alterations in

the immune response caused by infectious agents, particularly viruses.

Examples of autoimmune diseases include systemic lupus erythematosus,

rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes mellitus, myasthenia gravis, and multiple

sclerosis.

Type III hypersensitivities are induced when a profuse amount of antigen

enters the system and results in large quantities of antibody formation.

Type III hypersensitivity reactions occur when large quantities of antigen

react with host antibody to form small, soluble immune complexes that

settle in tissue cell membranes, causing chronic destructive

inflammation. The reactions appear hours or days after the antigen

challenge.

The mediators of type III hypersensitivity reactions include soluble IgA,

IgG, or IgM, and agents of the inflammatory response.

Two kinds of type III hypersensitivities are localized (Arthus) reactions

and systemic (serum sickness). Arthus reactions occur at the site of

injected drugs or booster immunizations. Systemic reactions occur

when repeated antigen challenges cause systemic distribution of the

immune complexes and subsequent inflammation of joints, lymph

nodes, and kidney tubules.

Autoimmune hypersensitivity reactions occur when autoantibodies or host

T cells mount an abnormal attack against self antigens. Autoimmune

antibody responses can be either local or systemic type II or type III

CHAPTER CHECKPOINTS

Normal

Myasthenia gravis

Myoneural junction

Acetylcholine

Receptors

Autoantibody

specific for

receptor

Paralysis

Muscle

Contraction

Postsynaptic

membrane

Neuron

X

X

X

Signal

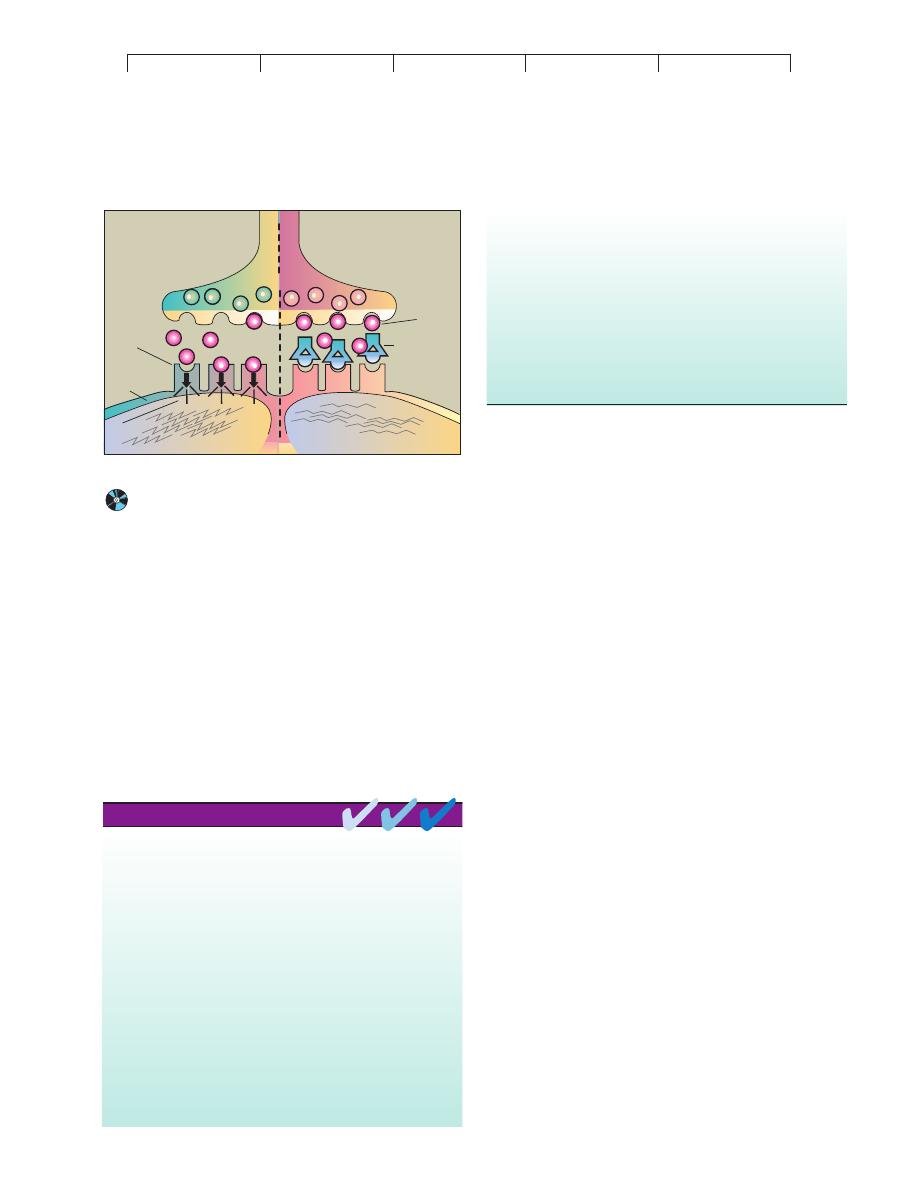

FIGURE 17.17

Proposed mechanisms for involvement of autoantibodies in

myasthenia gravis.

Antibodies developed against receptors on

the postsynaptic membrane block them so that acetylcholine cannot bind

and muscle contraction is inhibited.