Talaro−Talaro: Foundations

in Microbiology, Fourth

Edition

17. Disorders in Immunity

Text

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2002

Type IV Hypersensitivities: Cell-Mediated (Delayed) Reactions

517

both T cells and autoantibodies that severely compromises the ca-

pacity of neurons to send impulses. The principal motor and sen-

sory symptoms are muscular weakness and tremors, difficulties in

speech and vision, and some degree of paralysis. Most MS patients

first experience symptoms as young adults, and they tend to experi-

ence remissions (periods of relief) alternating with recurrences of

disease throughout their lives. Convincing evidence from studies of

the brain tissue of MS patients points to a strong connection

between the disease and infection with human herpesvirus 6 (see

chapter 24). The disease can be treated passively with monoclonal

antibodies that target T cells, and a vaccine containing the myelin

protein has shown beneficial effects. Immunosuppressants such as

cortisone and interferon B may also alleviate symptoms.

Type IV Hypersensitivities: Cell-Mediated

(Delayed) Reactions

The adverse immune responses we have covered so far are ex-

plained primarily by B-cell involvement and antibodies. But type

IV hypersensitivity involves primarily the T-cell branch of the im-

mune system. Type IV immune dysfunction has traditionally been

known as delayed hypersensitivity because the symptoms arise one

to several days following the second contact with an antigen. In

general, type IV diseases result when T cells respond to self tissues

or transplanted foreign cells. Examples of type IV hypersensitivity

include delayed allergic reactions to infectious agents, contact der-

matitis, and graft rejection.

DELAYED-TYPE HYPERSENSITIVITY

Infectious Allergy

A classic example of a delayed-type hypersensitivity occurs when a

person sensitized by tuberculosis infection is injected with an

extract (tuberculin) of the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

The so-called tuberculin reaction is an acute skin inflammation at

the injection site appearing within 24 to 48 hours. So useful and di-

agnostic is this technique for detecting present or prior tuberculosis

that it is the chosen screening device (figure 17.18a). Other infec-

tions that use similar skin testing are leprosy, syphilis, histoplasmo-

sis, toxoplasmosis, and candidiasis. This form of hypersensitivity

arises from time-consuming cellular events involving the T

D

class

of cells. After these cells receive processed microbial antigens from

macrophages, they release broad-spectrum cytokines that attract

inflammatory cells to the site

—particularly mononuclear cells,

fibroblasts, and other lymphocytes. In a chronic infection (tertiary

syphilis, for example), extensive damage to organs can occur

through granuloma formation.

Contact Dermatitis

The most common delayed allergic reaction, contact dermatitis, is

caused by exposure to resins in poison ivy or poison oak (Spotlight

on Microbiology 17.3), to simple haptens in household and per-

sonal articles ( jewelry, cosmetics, elasticized undergarments), and

to certain drugs. Like immediate atopic dermatitis, the reaction to

these allergens requires a sensitizing and a provocative dose. The

hypersensitivity reactions. Autoimmune T-cell responses are type IV

hypersensitivity reactions.

Susceptibility to autoimmune disease appears to be influenced by gender

and by genes in the MHC complex.

Autoimmune disease may be an excessive response of a normal immune

function, the appearance of sequestered antigens, “forbidden’’ clones

of lymphocytes that react to self antigens, or the result of alterations in

the immune response caused by infectious agents, particularly viruses.

Examples of autoimmune diseases include systemic lupus erythematosus,

rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes mellitus, myasthenia gravis, and multiple

sclerosis.

Type III hypersensitivities are induced when a profuse amount of antigen

enters the system and results in large quantities of antibody formation.

Type III hypersensitivity reactions occur when large quantities of antigen

react with host antibody to form small, soluble immune complexes that

settle in tissue cell membranes, causing chronic destructive

inflammation. The reactions appear hours or days after the antigen

challenge.

The mediators of type III hypersensitivity reactions include soluble IgA,

IgG, or IgM, and agents of the inflammatory response.

Two kinds of type III hypersensitivities are localized (Arthus) reactions

and systemic (serum sickness). Arthus reactions occur at the site of

injected drugs or booster immunizations. Systemic reactions occur

when repeated antigen challenges cause systemic distribution of the

immune complexes and subsequent inflammation of joints, lymph

nodes, and kidney tubules.

Autoimmune hypersensitivity reactions occur when autoantibodies or host

T cells mount an abnormal attack against self antigens. Autoimmune

antibody responses can be either local or systemic type II or type III

CHAPTER CHECKPOINTS

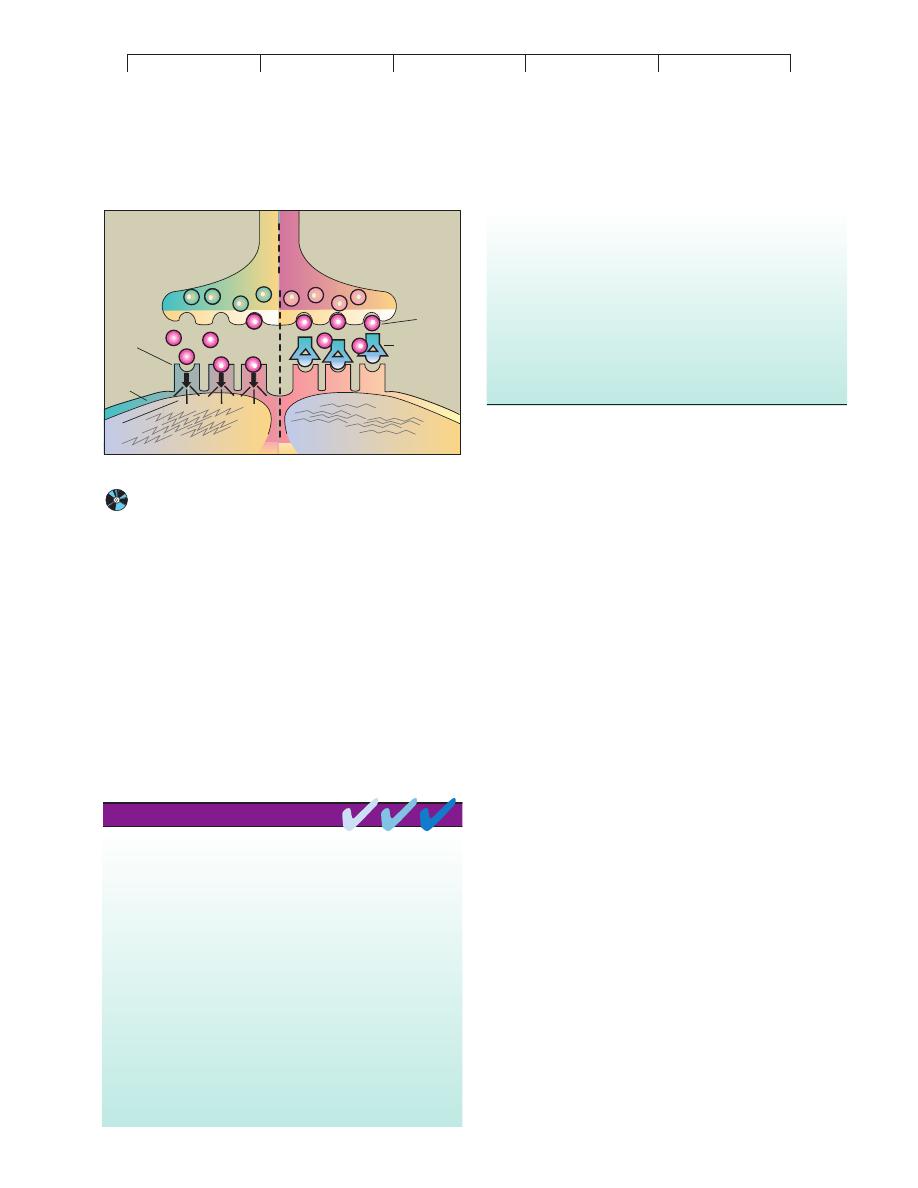

Normal

Myasthenia gravis

Myoneural junction

Acetylcholine

Receptors

Autoantibody

specific for

receptor

Paralysis

Muscle

Contraction

Postsynaptic

membrane

Neuron

X

X

X

Signal

FIGURE 17.17

Proposed mechanisms for involvement of autoantibodies in

myasthenia gravis.

Antibodies developed against receptors on

the postsynaptic membrane block them so that acetylcholine cannot bind

and muscle contraction is inhibited.

Talaro−Talaro: Foundations

in Microbiology, Fourth

Edition

17. Disorders in Immunity

Text

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2002

518

CHAPTER 17 Disorders in Immunity

allergen first penetrates the outer skin layers, is processed by

Langerhans cells (skin macrophages), and is presented to T cells.

When subsequent exposures attract lymphocytes and macrophages

to this area, these cells give off enzymes and inflammatory

cytokines that severely damage the epidermis in the immediate

vicinity. This response accounts for the intensely itchy papules and

blisters that are the early symptoms (figure 17.18b). As healing pro-

gresses, the epidermis is replaced by a thick, horny layer. Depend-

ing upon the dose and the sensitivity of the individual, the time

from initial contact to healing can be a week to 10 days.

(a)

(b)

FIGURE 17.18

Common delayed-type reactions.

(a) Positive tuberculin test.

Intradermal injection of tuberculin extract in a person sensitized to

tuberculosis yields a slightly raised red bump greater than 10 mm in

diameter. (b) Contact dermatitis from poison oak, showing various stages

of involvement: blisters, scales, and thickened patches.

T CELLS AND THEIR ROLE IN

ORGAN TRANSPLANTATION

Transplantation or grafting of organs and tissues is a common med-

ical procedure. Although it is life-giving, this technique is plagued

by the natural tendency of lymphocytes to seek out foreign antigens

and mount a campaign to destroy them. The bulk of the damage that

occurs in graft rejections can be attributed to expression of cyto-

toxic T cells and other killer cells. This section will cover the mech-

anisms involved in graft rejection, tests for transplant compatibility,

reactions against grafts, prevention of graft rejection, and types of

grafts.

The Genetic and Biochemical Basis

for Graft Rejection

In chapter 15, we discussed the role of major histocompatibility

(MHC or HLA) genes and receptors in immune function. In gen-

eral, the genes and receptors in MHC classes I and II are extremely

important in recognizing self and in regulating the immune re-

sponse. These receptors also set the events of graft rejection in mo-

tion. The MHC genes of humans are inherited from among a large

pool of genes, so the cells of each person can exhibit variability in

the pattern of cell surface molecules (figure 17.19). The pattern is

identical in different cells of the same person and can be similar in

related siblings and parents, but the more distant the relationship,

the less likely that the MHC genes and receptors will be similar.

When donor tissue (a graft) displays surface receptors of a different

MHC class, the T cells of the recipient (called the host) will recog-

nize its foreignness and react against it.

T Cell-Mediated Recognition of Foreign

MHC Receptors

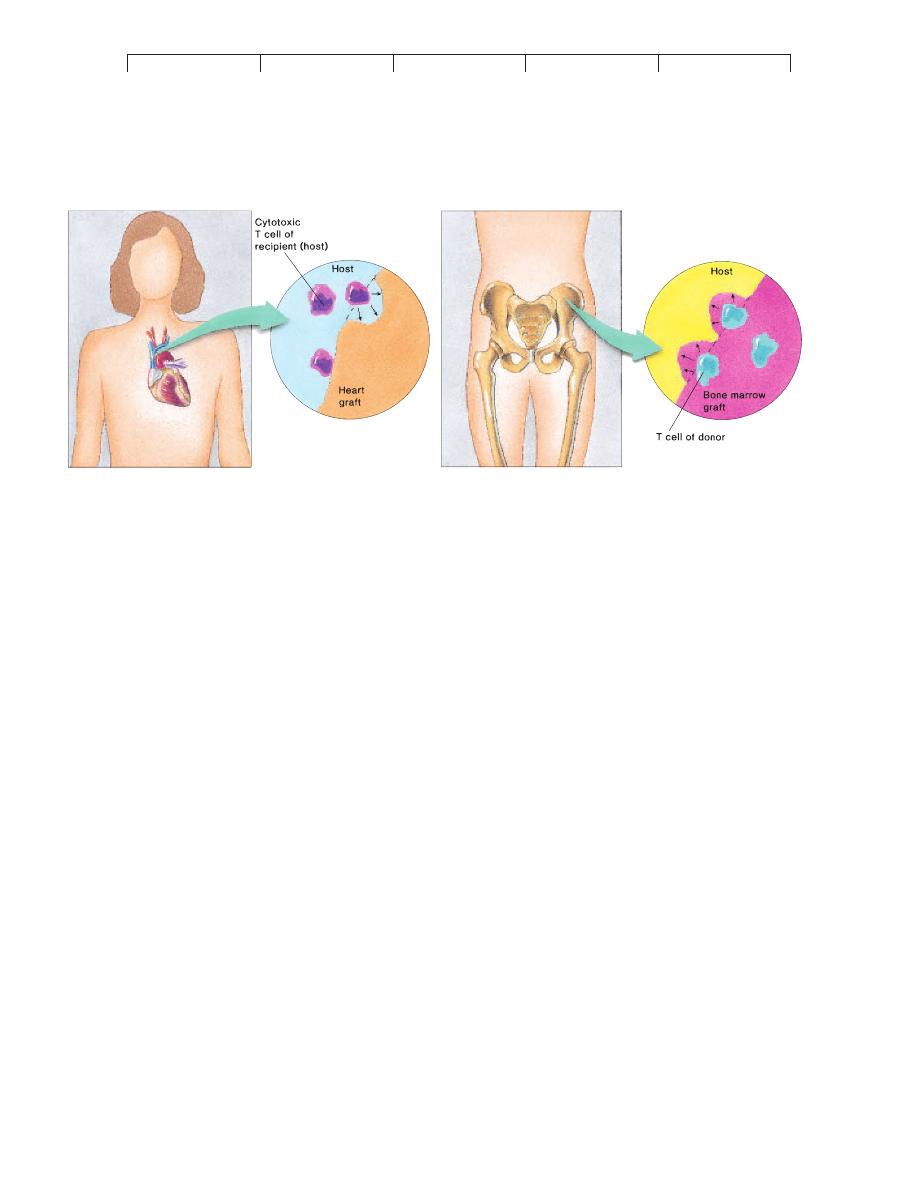

Host Rejection of Graft

When the cytotoxic T cells of a host

recognize foreign class I MHC receptors on the surface of grafted

cells, they release interleukin-2 as part of a general immune mo-

bilization. Receipt of this stimulus amplifies helper and cytotoxic

T cells specific to the foreign antigens on the donated cells. The

cytotoxic cells bind to the grafted tissue and secrete lymphokines

that begin the rejection process within 2 weeks of transplantation

(figure 17.20a). Late in this process, antibodies formed against the

graft tissue contribute to immune damage. A final blow is the destruc-

tion of the vascular supply, promoting death of the grafted tissue.

Graft Rejection of Host

In certain severe immunodeficiencies,

the host cannot or does not reject a graft. But this failure may not

protect the host from serious damage, because graft incompatibility

is a two-way phenomenon. Some grafted tissues (especially bone

marrow) contain an indigenous population called passenger lym-

phocytes. This makes it quite possible for the graft to reject the

host, causing graft versus host disease (GVHD) (figure 17.20b).

Since any host tissue bearing MHC receptors foreign to the graft

can be attacked, the effects of GVHD are widely systemic and

toxic. A papular, peeling skin rash is the most common symptom.

Other organs affected are the liver, intestine, muscles, and mucous

membranes. GVHD occurs in approximately 30% of bone marrow

transplants within 100 to 300 days of the graft. A relatively high

percentage of recipients die from its effects.

Talaro−Talaro: Foundations

in Microbiology, Fourth

Edition

17. Disorders in Immunity

Text

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2002

Type IV Hypersensitivities: Cell-Mediated (Delayed) Reactions

519

A

B

1

B

C

2

B

D

3

A

D

4

B

D

5

A

C

6

A

B

C D

Male

Female

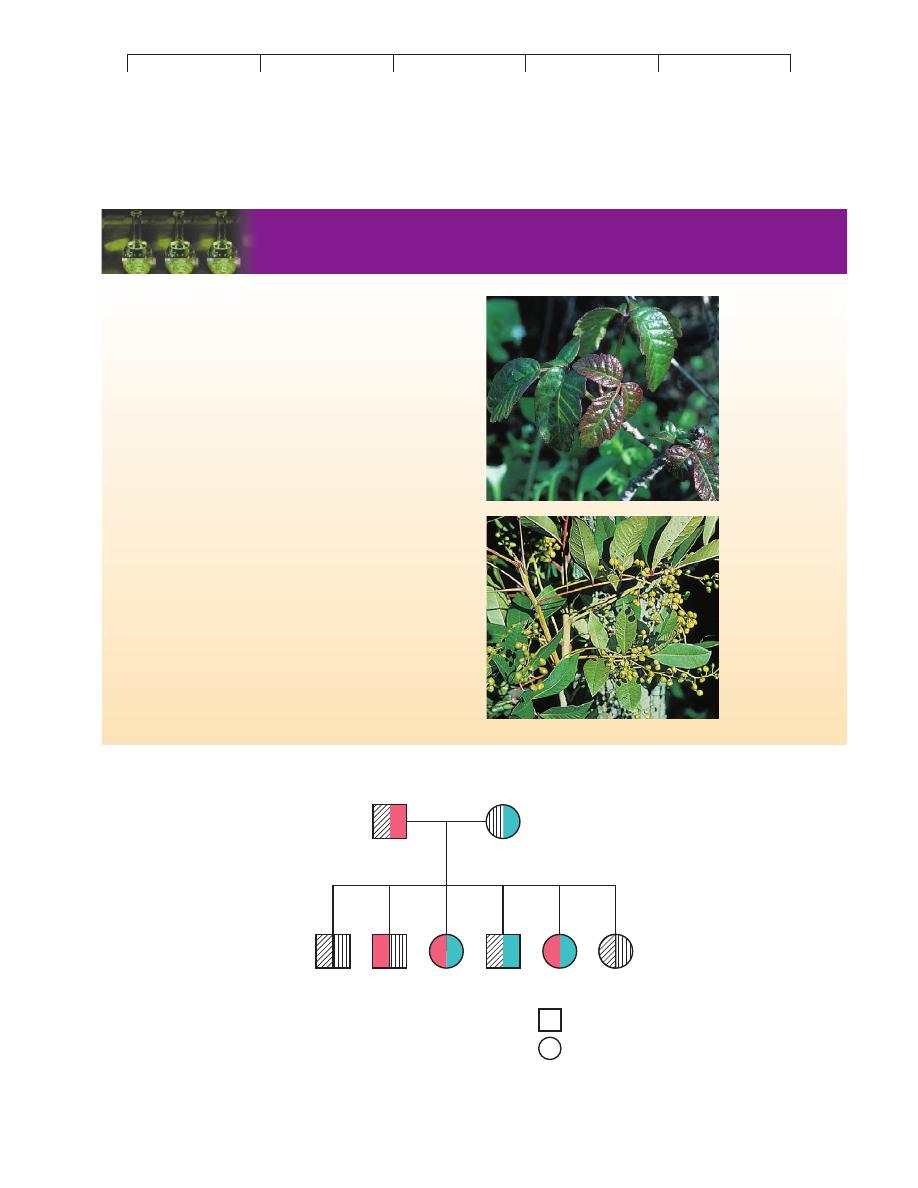

SPOTLIGHT ON MICROBIOLOGY

17.3

Pretty, Pesky, Poisonous Plants

As a cause of allergic contact dermatitis (affecting about 10 million peo-

ple a year), nothing can compare with a single family of plants belonging

to the genus Toxicodendron. At least one of these plants

—either poison

ivy, poison oak, or poison sumac

—flourishes in the forests, woodlands,

or along the trails of most regions of America. The allergen in these

plants, an oil called urushiol, has such extreme potency that a pinhead-

sized amount could spur symptoms in 500 people, and it is so long-

lasting that botanists must be careful when handling 100-year-old plant

specimens. Although degrees of sensitivity vary among individuals, it is

estimated that 85% of all Americans are potentially hypersensitive to this

compound. Some people are so acutely sensitive that even the most

miniscule contact, such as handling pets or clothes that have touched the

plant or breathing vaporized urushiol, can trigger an attack.

Humans first become sensitized by contact during childhood. Indi-

viduals at great risk (firefighters, hikers) are advised to determine their

degree of sensitivity using a skin test, so that they can be adequately cau-

tious and prepared. Some odd remedies include skin potions containing

bleach, buttermilk, ammonia, hair spray, and meat tenderizer. Commer-

cial products are available for blocking or washing away the urushiol.

Allergy researchers are currently testing oral vaccines containing a form

of urushiol, which seem to desensitize experimental animals. An effec-

tive method using poison ivy desensitization injection is currently avail-

able to people with extreme sensitivity.

Learning to identify these common plants can prevent exposure and

sensitivity. One old saying that might help warns, “Leaves of three, let

it be; berries white, run with fright.” (See chapter opening photo of

poison ivy.)

Poison oak

Poison sumac

FIGURE 17.19

The pattern of inheritance of MHC (HLA) genes.

A simplified version of the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) complex in a family. In this example,

there are two genes in the complex, and each parent has a different set of genes (A/B and C/D). A child can inherit one of four different

combinations. Out of six children, two sets (1 and 6, 3 and 5) have identical HLA genes and are good candidates for exchange grafts. Children

sharing one gene (for example, 1, 4, and 6 share antigen A) are close matches, but two pairs of children (2 and 4, 3 and 6) do not match at all.

Talaro−Talaro: Foundations

in Microbiology, Fourth

Edition

17. Disorders in Immunity

Text

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2002

520

CHAPTER 17 Disorders in Immunity

Classes of Grafts

Grafts are generally classified according to the genetic relationship

between the donor and the recipient. Tissue transplanted from one

site on an individual’s body to another site on his body is known as

an autograft. Typical examples are skin replacement in burn repair

and the use of a vein to fashion a coronary artery bypass. In an iso-

graft, tissue from an identical twin is used. Because isografts do

not contain foreign antigens, they are not rejected, but this type of

grafting has obvious limitations. Allografts, the most common

type of grafts, are exchanges between genetically different individ-

uals belonging to the same species (two humans). A close genetic

correlation is sought for most allograft transplants (see next sec-

tion). A xenograft is a tissue exchange between individuals of

different species. Until rejection can be better controlled, most

xenografts are experimental or for temporary therapy only.

Avoiding and Controlling Graft Incompatibility

Graft rejection can be averted or lessened by directly comparing the

tissue of the recipient with that of potential donors. Several tissue

matching procedures are used. In the mixed lymphocyte reaction

(MLR), lymphocytes of the two individuals are mixed and incu-

bated. If an incompatibility exists, some of the cells will become

activated and proliferate. Tissue typing is similar to blood typing,

except that specific antisera are used to disclose the HLA antigens

on the surface of lymphocytes. In most grafts (one exception is

bone marrow transplants), the ABO blood type must also be

matched. Although a small amount of incompatibility is tolerable in

certain grafts (liver, heart, kidney), a closer match is more likely to

be successful, so the closest match possible is sought.

Drugs That Suppress Allograft Rejection

Despite an interna-

tional computerized hotline for matching recipients with donors

and a greater availability of viable organs than in the past, an ideal

match between donor and recipient is still the exception rather than

the rule, and some sort of immunosuppressive therapy to overcome

rejection is usually required. Rejection can be controlled with

agents such as cyclosporin A, methotrexate, prednisone, and a

monoclonal antibody OKT3. Except for cyclosporin A, interven-

tion with drugs can be complicated by general suppression of the

immune system (especially T cells) and frequent opportunistic

infections.

Cyclosporin A is a polypeptide isolated from a fungus. It has

dramatically improved the survival rate of allograft patients

(kidney, heart, liver, and bone marrow) and has reduced the inci-

dence of fatal infections. Although its action is not entirely under-

stood, cyclosporin appears to block the activation of T helper cells

and interfere with the release of interleukin-2. What makes this

drug so valuable is that it does not inhibit important lymphoid cells

and phagocytes, and the body is better able to ward off infections.

Its adverse effects of kidney toxicity and increased blood pressure

can be reduced by adjusting the dose and monitoring blood levels

of the drug. Because of its ability to inhibit undesirable T-cell ac-

tivity, cyclosporin is also being used to treat autoimmune diseases

such as type I diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis. Newer drugs aim

to block the binding of IL-2 on T cells.

Types of Transplants

Today, transplantation is a recognized medical procedure whose

benefit is reflected in several thousand transplants each year. It has

been performed on every major organ, including parts of the brain.

The most frequent transplant operations involve skin, heart, kidney,

coronary artery, cornea, and bone marrow. The sources of organs

and tissues are live donors (kidney, skin, bone marrow, liver), ca-

davers (heart, kidney, cornea), and fetal tissues. In the past decade,

we have witnessed some unusual types of grafts. For instance, the

fetal pancreas has been implanted as a potential treatment for

diabetes, and fetal brain tissues for Parkinson disease. Part of a liver

has been transplanted from a live parent to a child, and parents have

donated a lobe from their lungs to help restore function in their

children with severe cystic fibrosis.

FIGURE 17.20

Potential reactions in transplantation.

(a) The host’s immune system (primarily cytotoxic T cells) encounters the cells of the donated organ (heart)

and rejects the organ by secreting cytokines. (b) Grafted tissue (bone marrow) contains endogenous T cells that recognize the host’s tissues as

foreign and mount a cytokine attack. The recipient will develop symptoms of graft versus host disease.

(a)

(b)

Talaro−Talaro: Foundations

in Microbiology, Fourth

Edition

17. Disorders in Immunity

Text

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2002

Immunodeficiency Diseases: Hyposensitivity of the Immmune System

521

Bone marrow transplantation is a rapidly growing medical

procedure for patients with immune deficiencies, aplastic anemia,

leukemia and other cancers, and radiation damage. This procedure

is extremely expensive, costing up to $200,000 per patient. Before

bone marrow from a closely matched donor can be infused (Med-

ical Microfile 17.4), the patient is pretreated with chemotherapy

and whole-body irradiation, a procedure designed to destroy his

own blood stem cells and thus prevent rejection of the new marrow

cells. Within 2 weeks to a month after infusion, the grafted cells are

established in the host. Because donor lymphoid cells can still

cause GVHD, anti-rejection drugs may be necessary. An amazing

consequence of bone marrow transplantation is that a recipient’s

blood type may change to the blood type of the donor.

Immunodeficiency Diseases:

Hyposensitivity of the Immune System

It is a marvel that development and function of the immune system

proceed as normally as they do. On occasion, however, an error oc-

curs and a person is born with or develops weakened immune re-

sponses. In many cases, these very “experiments’’ of nature have

provided penetrating insights into the exact functions of certain

cells, tissues, and organs because of the specific signs and symp-

toms shown by the immunodeficient individuals. The predominant

consequences of immunodeficiencies are recurrent, overwhelming

infections, often with opportunistic microbes. Immunodeficiencies

fall into two general categories: primary diseases, present at birth

(congenital) and usually stemming from genetic errors, and sec-

ondary diseases, acquired after birth and caused by natural or arti-

ficial agents (table 17.5).

PRIMARY IMMUNODEFICIENCY DISEASES

Deficiencies affect both specific immunities such as antibody

production and less-specific ones such as phagocytosis. Consult

figure 17.21 to survey the places in the normal sequential develop-

ment of lymphocytes where defects can occur and the possible

consequences. In many cases, the deficiency is due to an inherited

abnormality, though the exact nature of the abnormality is not

known for a number of diseases. Because the development of B cells

and T cells departs at some point, an individual can lack one or both

cell lines. It must be emphasized, however, that some deficiencies

affect other cell functions. For example a T-cell deficiency can af-

fect B-cell function because of the role of T helper cells. In some

deficiencies, the lymphocyte in question is completely absent or is

present at very low levels, whereas in others, lymphocytes are pres-

ent but do not function normally.

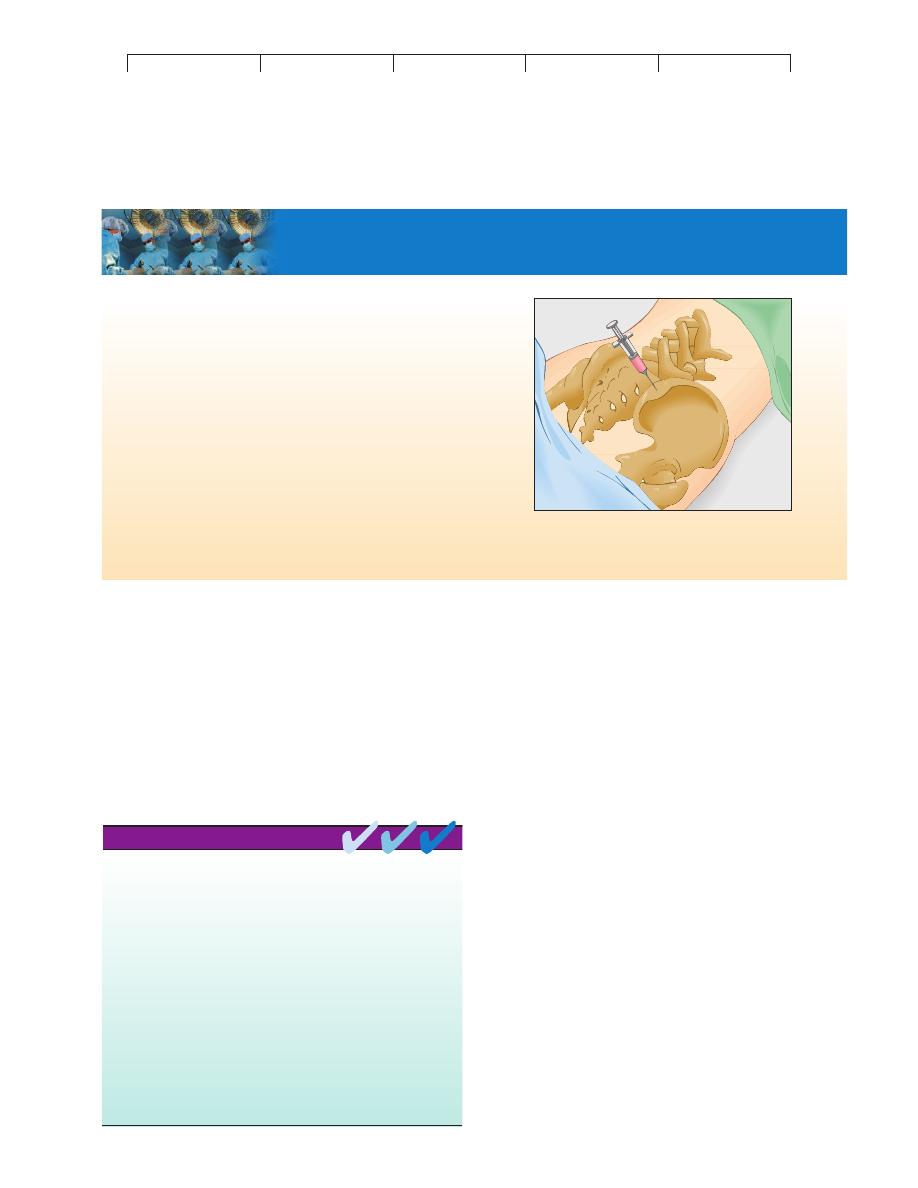

MEDICAL MICROFILE

17.4

The Mechanics of Bone Marrow Transplantation

In some ways, bone marrow is the most exceptional form of transplanta-

tion. It does not involve invasive surgery in either the donor or recipient,

and it permits the removal of tissue from a living donor that is fully re-

placeable. While the donor is sedated, a bone marrow/blood sample is

aspirated by inserting a special needle into an accessible marrow cavity.

The most favorable sites are the crest and spine of the ilium (major bone

of the pelvis). During this procedure, which lasts 1 to 2 hours, 3% to 5% of

the donor’s marrow is withdrawn in 20 to 30 separate extractions. Between

500 and 800 ml of marrow is removed. The donor may experience some

pain and soreness, but there are rarely any serious complications. In a few

weeks, the depleted marrow will naturally replace itself. Implanting the

harvested bone marrow is rather convenient, because it is not necessary to

place it directly into the marrow cavities of the recipient. Instead, it is

dripped intravenously into the circulation, and the new marrow cells auto-

matically settle in the appropriate bone marrow regions. The survival and

permanent establishment of the marrow cells are increased by administer-

ing various growth factors and stem cell stimulants to the patient.

Removal of a bone marrow sample for transplantation. Samples are

removed by inserting a needle into the spine or crest of the ilium. (The

ilium is a prolific source of bone marrow.)

Type IV hypersensitivity reactions occur when cytotoxic T cells attack

either self tissue or transplanted foreign cells. Type IV reactions are

also termed delayed hypersensitivity reactions because they occur

hours to days after the antigenic challenge.

Type IV hypersensitivity reactions are mediated by T lymphocytes and

are carried out against foreign cells that show both a foreign MHC and

a nonself receptor site.

Examples of type IV reactions include the tuberculin reaction, contact

dermatitis, and mismatched organ transplants (host rejection and GVHD

reactions).

The four classes of transplants or grafts are determined by the degree of

MHC similarity between graft and host. From most to least similar,

these are: autografts, isografts, allografts, and xenografts.

Graft rejection can be minimized by tissue matching procedures,

immunosuppressive drugs, and use of tissues that do not provoke a

type IV response.

CHAPTER CHECKPOINTS