1

PROF.DR. MAHA SHAKIR HASSAN

Lec 2

Stomach

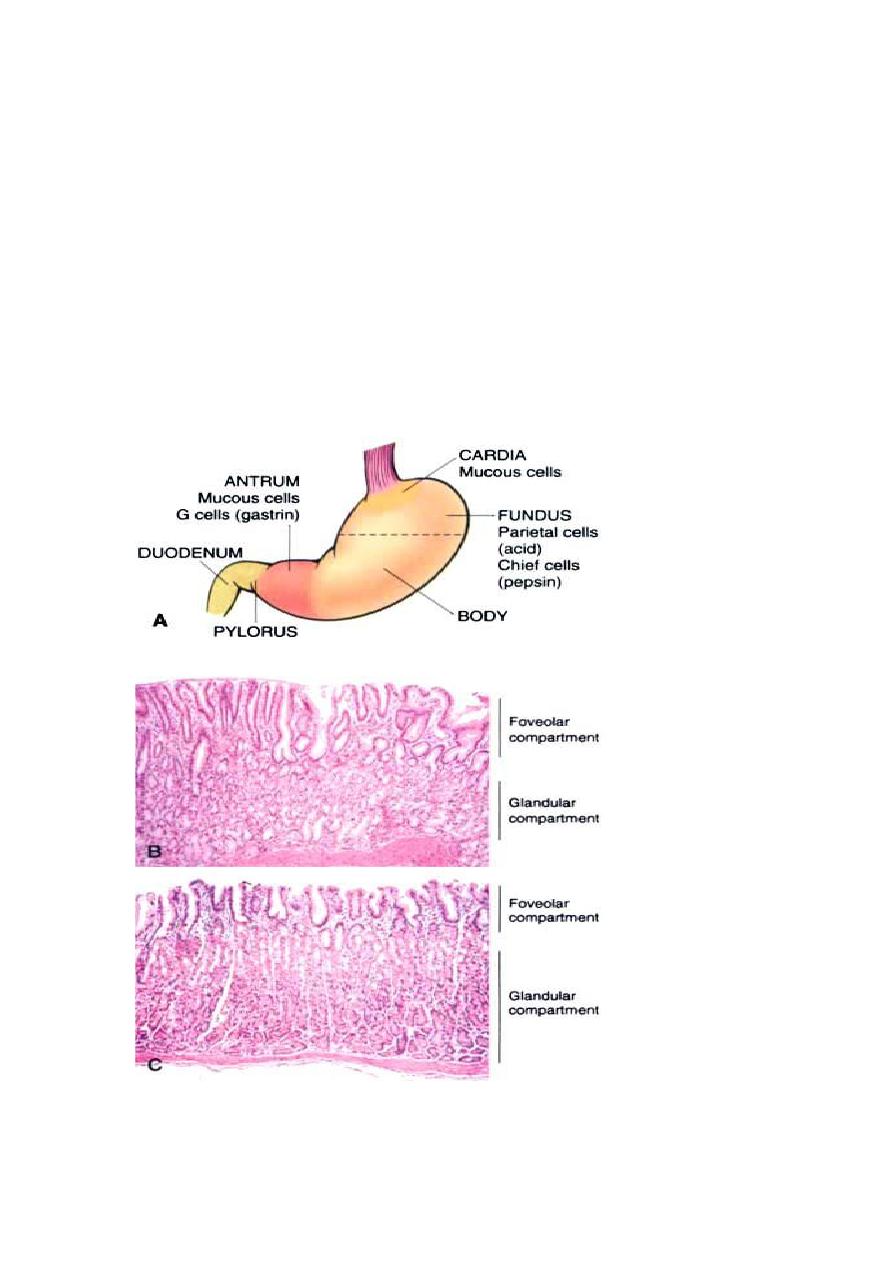

The stomach is divided into four major anatomic regions: the cardia, fundus,

body, and antrum. The cardia and antrum are lined mainly by mucin-

secreting foveolar cells that form small glands. The antral glands are similar

but also contain endocrine cells, such as G cells, that release gastrin to

stimulate luminal acid secretion by parietal cells within the gastric fundus

and body. The well-developed glands of the body and fundus also contain

chief cells that produce and secrete digestive enzymes such as pepsin.

Fig:B microscopical view of antral mucosa.

C microscopical view of funduc mucosa.

2

Congenital anomalies

Pyloric Stenosis

Congenital hypertrophic pyloric stenosis generally presents in the second or

third week of life as new-onset regurgitation and persistent, projectile

vomiting. Physical examination reveals hyperperistalsis and a firm, ovoid

abdominal mass.

Diaphragmatic Hernia.

Diaphragmatic hernia occurs when incomplete formation of the diaphragm

allows the abdominal viscera to herniate into the thoracic cavity. When

severe, the space-filling effect of the displaced viscera can cause pulmonary

hypoplasia that is incompatible with life after birth.

GASTRITIS

Acute Gastritis

Acute gastritis is an acute mucosal inflammatory process, usually of a

transient nature. The inflammation may be accompanied by hemorrhage into

the mucosa and, in more severe circumstances, by sloughing of the

superficial mucosal epithelium (erosion). This severe erosive form of the

disease is an important cause of acute gastrointestinal bleeding.

Acute gastritis is frequently associated with the following:

• Heavy use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), particularly

aspirin.

• Excessive alcohol consumption

• Heavy smoking

• Treatment with cancer chemotherapeutic drugs

• Uremia

• Severe stress (e.g., trauma, burns, surgery)

ACUTE GASTRIC ULCERATION

Focal, acutely developing gastric mucosal defects are a well-known

complication of therapy with NSAIDs. They may also appear after severe

physiologic stress. Some of these are given specific names, based on location

and clinical associations. For example:

• Stress ulcers are most common in individuals with shock, sepsis, or

3

severe trauma.

• Ulcers occurring in the proximal duodenum and associated with severe

burns or trauma are called Curling ulcers.

• Gastric, duodenal, and esophageal ulcers arising in persons with

intracranial disease are termed Cushing ulcers and carry a high

incidence of perforation

Chronic Gastritis

In contrast to acute gastritis, the symptoms associated with chronic

gastritis are typically less severe but more persistent. Nausea and

upper abdominal discomfort may occur, sometimes with vomiting,

but hematemesis is uncommon. The most common cause of chronic

gastritis is infection with the bacillus Helicobacter pylori.

Autoimmune gastritis, the most common cause of atrophic

gastritis, represents less than 10% of cases of chronic gastritis and

is the most common form of chronic gastritis in patients without H.

pylori infection. Less common etiologies include radiation injury,

chronic bile reflux.

HELICOBACTER PYLORI GASTRITIS

These spiral-shaped or curved bacilli are present in gastric biopsy

specimens of almost all patients with duodenal ulcers and the

majority of individuals with gastric ulcers or chronic gastritis. H.

pylori organisms are present in 90% of individuals with chronic

gastritis affecting the antrum.

Pathogenesis.

H. pylori infection is the most common cause of chronic gastritis.

The disease most often presents as a predominantly antral gastritis

with high acid production, despite hypogastrinemia. The risk of

duodenal ulcer is increased in these patients and, in most, gastritis

is limited to the antrum with occasional involvement of the cardia.

In a subset of patients the gastritis progresses to involve the gastric

body and fundus. This pangastritis is associated with multifocal

mucosal atrophy, reduced acid secretion, intestinal metaplasia, and

increased risk of gastric adenocarcinoma.

Four features are linked to H. pylori virulence:

• Flagella, which allow the bacteria to be motile in viscous

mucus

4

• Urease, which generates ammonia from endogenous urea and

thereby elevates local gastric pH protect the bacteria from acid

media of stomach.

• Adhesins that enhance their bacterial adherence to surface

foveolar cells

• Toxins, that may be involved in ulcer or cancer development

by poorly defined mechanisms.

Morphology.

1. H. pylori in infected individuals. The organism is

concentrated within the superficial mucus overlying epithelial

cells.

2. The inflammatory infiltrate generally includes variable

numbers of neutrophils within the lamina propria, including

some that cross the basement membrane to assume an

intraepithelial location and accumulate in the lumen of gastric

pits to create pit abscesses. In addition, the superficial lamina

propria includes large numbers of plasma cells, and increased

numbers of lymphocytes and macrophages.

3. Lymphoid aggregates, some with germinal centers, are

frequently present that has the potential to transform into

lymphoma.

Clinical Features.

In addition to histologic identification of the organism, several

diagnostic tests have been developed including a noninvasive

serologic test for antibodies to H. pylori, fecal bacterial

detection

Effective

treatments

for

H.

pylori

infection

include

combinations of antibiotics and proton pump inhibitors.

Individuals with H. pylori gastritis usually improve after

treatment, although relapses can occur after incomplete

eradication or re-infection.

AUTOIMMUNE GASTRITIS

Autoimmune gastritis accounts for less than 10% of cases of

chronic gastritis. In contrast to that caused by H. pylori,

5

autoimmune gastritis typically spares the antrum and includes

hypergastrinemia . Autoimmune gastritis is characterized by:

• Antibodies to parietal cells and intrinsic factor that can be

detected in serum and gastric secretions

• Reduced serum pepsinogen I concentration

• Antral endocrine cell hyperplasia

• Vitamin B12 deficiency

• Defective gastric acid secretion (achlorhydria)

Pathogenesis.

Autoimmune gastritis is associated with loss of parietal cells,

which are responsible for secretion of gastric acid and intrinsic

factor. The absence of acid production stimulates gastrin release,

resulting in hypergastrinemia and hyperplasia of antral gastrin-

producing G cells. Lack of intrinsic factor disables ileal vitamin

B12 absorption, leading to B12 deficiency and a slow-onset

megaloblastic anemia (pernicious anemia). The reduced serum

pepsinogen I concentration results from chief cell destruction. In

contrast, although H. pylori can cause hypochlorhydria, it is not

associated with achlorhydria or pernicious anemia because the

parietal and chief cell damage is not as severe as in autoimmune

gastritis.

Morphology.

1. diffuse mucosal damage of the oxyntic (acid-producing)

mucosa within the body and fundus.

2. With diffuse atrophy, the oxyntic mucosa of the body and

fundus appears markedly thinned, and rugal folds are lost.

3. the inflammatory infiltrate is more often composed of

lymphocytes, macrophages, and plasma cells. Lymphoid

aggregates may be present. The superficial lamina propria

plasma cells of H. pylori gastritis are typically absent, and the

6

inflammatory reaction is most often deep and centered on the

gastric glands .

4. Loss of parietal and chief cells can be extensive. With areas

of intestinal metaplasia, characterized by the presence of

goblet cells and columnar absorptive cells .

TABLE :Characteristics of Helicobacter pylori–Associated and Autoimmune

Gastritis

H. pylori–Associated

Autoimmune

Location

Antrum

Body

Inflammatory

infiltrate

Neutrophils, subepithelial

plasma cells

Lymphocytes, macrophages

Acid production Increased to slightly decreased

Decreased

Gastrin

Normal to decreased

Increased

Serology

Antibodies to H. pylori

Antibodies to parietal cells

Sequelae

Peptic ulcer, adenocarcinoma

Atrophy, pernicious anemia,

adenocarcinoma, carcinoid tumor

Associations

Low socioeconomic status,

poverty, residence in rural areas

Autoimmune disease; thyroiditis,

diabetes mellitus, Graves disease

7

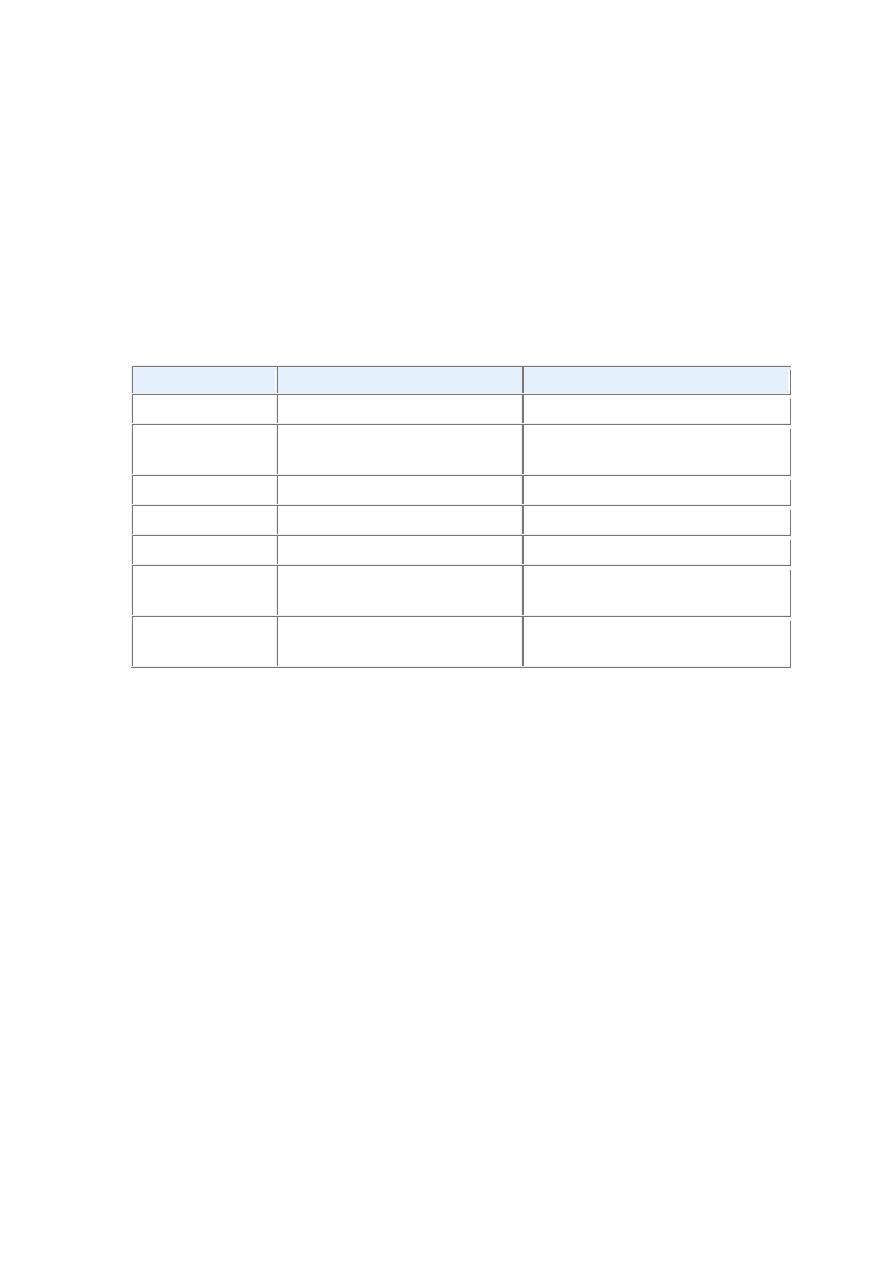

FIGURE Helicobacter pylori gastritis. A, Spiral-shaped H. pylori are highlighted in this Warthin-Starry

silver stain. Organisms are abundant within surface mucus. B, Intraepithelial and lamina propria

neutrophils are prominent. C, Lymphoid aggregates with germinal centers and abundant subepithelial

plasma cells within the superficial lamina propria are characteristic of H. pylori gastritis.

FIGURE Autoimmune gastritis. A, Low-magnification image of gastric body demonstrating deep

inflammatory infiltrates, primarily composed of lymphocytes, and glandular atrophy. B, Intestinal

metaplasia, recognizable as the presence of goblet cells admixed with gastric foveolar epithelium.

8

Peptic ulcer disease

Ulcers are defined as a breach in the mucosa of the alimentary tract that

extends through the muscularis mucosae into the submucosa or deeper. This

is to be contrasted to erosions, in which there is a breach in the epithelium of

the mucosa only.

Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) is most often associated with H. pylori–induced

hyperchlorhydric chronic gastritis, which is present in 85% to 100% of

individuals with duodenal ulcers and in 65% with gastric ulcers.

PUD may occur in any portion of the GI tract exposed to acidic gastric

juices, but is most common in the gastric antrum and first portion of the

duodenum. PUD may also occur in the esophagus as a result of GERD or

acid secretion by ectopic gastric mucosa. Gastric mucosa within a Meckel

diverticulum can result in peptic ulceration of adjacent mucosa.

Peptic Ulcers

Peptic ulcers are chronic, most often solitary, lesions that occur in any

portion of the gastrointestinal tract exposed to the aggressive action of acid-

peptic juices. At least 98% of peptic ulcers are either in the first portion of

the duodenum or in the stomach, in a ratio of about 4:1.

Pathogenesis. There are two key facts.

First, the mucosal exposure to gastric acid and pepsin.

Second, there is a very strong causal association with H. pylori infection.

It is best perhaps to consider that peptic ulcers are induced by an imbalance

between the gastroduodenal mucosal defenses and the countervailing

aggressive forces that overcome such defenses.

The array of host mechanisms that prevent the gastric mucosa from being

digested like a piece of meat include the following:

• Secretion of mucus by surface epithelial cells

• Secretion of bicarbonate into the surface mucus, to create a buffered surface

microenvironment

• Secretion of acid- and pepsin-containing fluid from the gastric pits as “jets”

through the surface mucus layer, entering the lumen directly without

contacting surface epithelial cells

• Rapid gastric epithelial regeneration

• Robust mucosal blood flow, to sweep away hydrogen ions that have back-

9

diffused into the mucosa from the lumen and to sustain the high cellular

metabolic and regenerative activity

• Mucosal elaboration of prostaglandins, which help maintain mucosal blood

flow

The imbalances of mucosal defenses and damaging forces that cause chronic

gastritis are also responsible for PUD. Thus, PUD generally develops on a

background of chronic gastritis. The reasons why some people develop only

chronic gastritis while others develop PUD are poorly understood.

H. pylori infection and NSAID use are the primary underlying causes of

PUD, and both compromise mucosal defense while causing mucosal damage.

Although more than 70% of individuals with PUD are infected by H. pylori,

fewer than 20% of H. pylori–infected individuals develop peptic ulcer. It is

probable that host factors as well as variation among H. pylori strains

determine the clinical outcomes.

The gastric hyperacidity that drives PUD may be caused by:

• H. pylori infection, parietal cell hyperplasia.

• excessive secretory responses.

• or impaired inhibition of stimulatory mechanisms such as gastrin

release. For example, Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, in which there are

multiple peptic ulcerations in the stomach, duodenum, and even

jejunum, is caused by uncontrolled release of gastrin by a tumor and

the resulting massive acid production.

More common cofactors in peptic ulcerogenesis include:

• chronic NSAID use, which causes direct chemical irritation while

suppressing prostaglandin synthesis necessary for mucosal

protection.

• cigarette smoking, which impairs mucosal blood flow and healing.

• and high-dose corticosteroids that suppress prostaglandin synthesis

and impair healing.

Duodenal ulcers are more frequent in individuals with:

• alcoholic cirrhosis.

• chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

• chronic renal failure.

• and hyperparathyroidism.

10

In the latter two conditions, hypercalcemia stimulates gastrin production

and therefore increases acid secretion. Finally, self-imposed or exogenous

psychologic stress may increase gastric acid production.

MORPHOLOGY

Peptic ulcers are four times more common in the proximal duodenum than in

the stomach. Duodenal ulcers usually occur within a few centimeters of the

pyloric valve and involve the anterior duodenal wall. Gastric peptic ulcers

are predominantly located along the lesser curvature near the interface of the

body and antrum.

Peptic ulcers are solitary in more than 80% of patients. Lesions less than 0.3

cm in diameter tend to be shallow while those over 0.6 cm are likely to be

deeper ulcers. The classic peptic ulcer is a round to oval, sharply punched-

out defect. The mucosal margin is usually level with the surrounding

mucosa. In contrast, heaped-up margins are more characteristic of

cancers. The depth of ulcers may be limited by the thick gastric muscularis

propria or by adherent pancreas, omental fat, or the liver. Perforation into

the peritoneal cavity is a surgical emergency that may be identified by the

presence of free air under the diaphragm on upright radiographs of the

abdomen.

The base of peptic ulcers is smooth and clean as a result of peptic digestion

of exudate.

Size and location do not differentiate benign and malignant ulcers. However,

the gross appearance of chronic peptic ulcers is virtually diagnostic.

Malignant transformation of peptic ulcers is very rare.

11

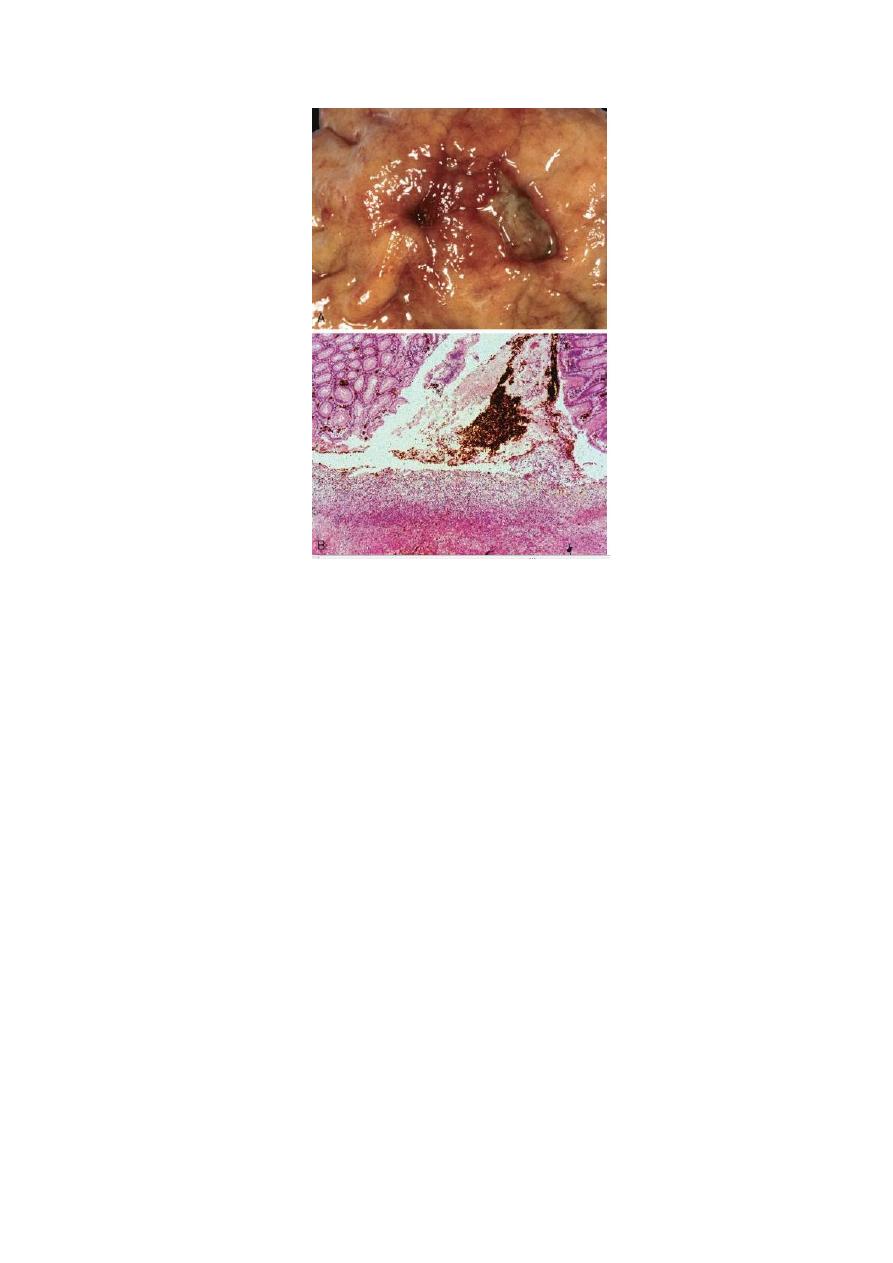

FIGURE Acute gastric perforation in a patient presenting with free air under the diaphragm. A, Mucosal

defect with clean edges. B, The necrotic ulcer base is composed of granulation tissue.

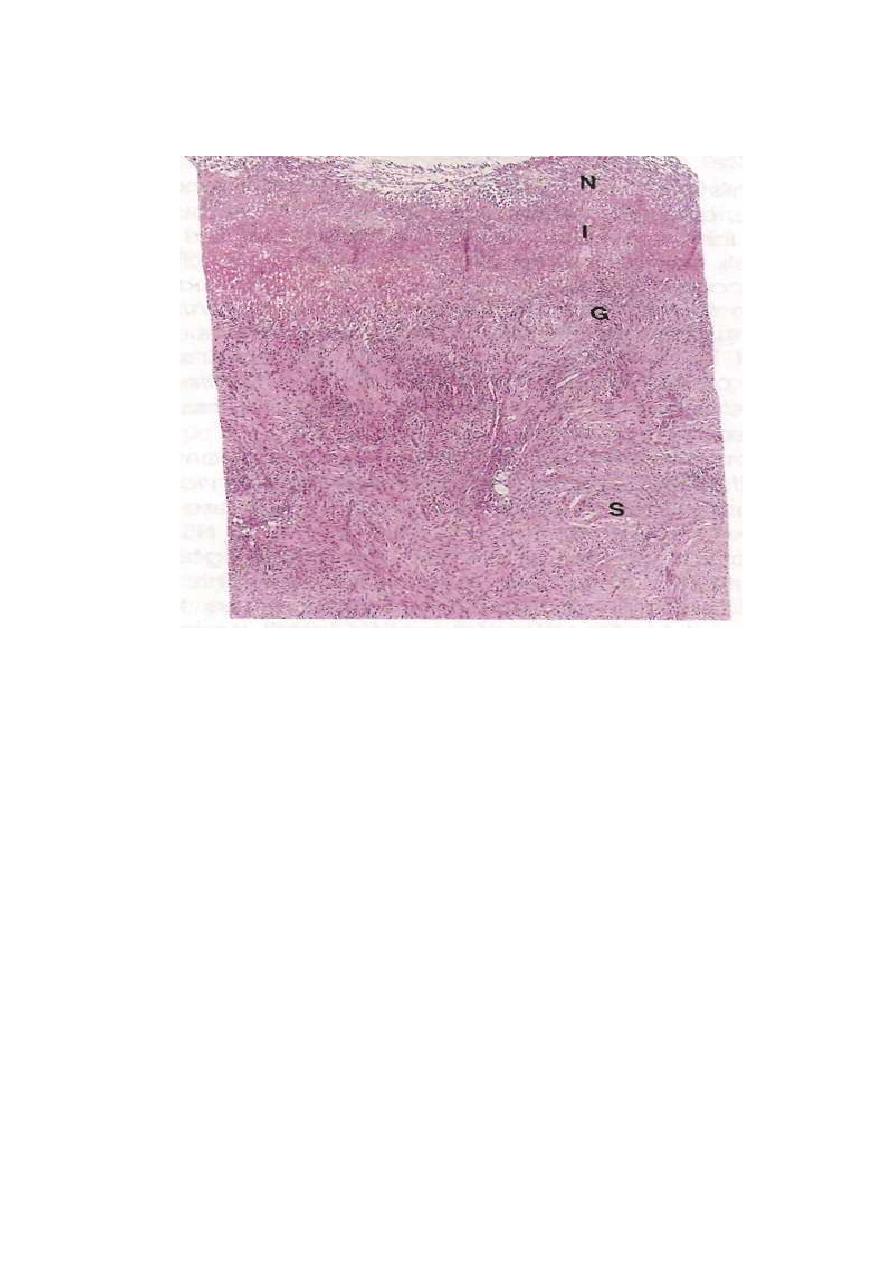

histologic appearance: four zones can be distinguished

1- the base and margins have a thin layer of necrotic fibrinoid debris

underlain by (2) a zone of active nonspecific inflammatory infiltration with

neutrophils predominating, underlain by (3) granulation tissue, deep to which

is (4) fibrous, collagenous scar that fans out widely from the margins of the

ulcer. Vessels trapped within the scarred area are characteristically thickened

and occasionally thrombosed.

12

Medium-power detail of the base of a nonperforated peptic ulcer, demonstraiting the layers of necrosis (N),

inflammation (I), granulation tissue (G), and scar (s) moving from the luminal surface at the top End the

muscle wall at the bottom.