Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

• Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) represents a

monoclonal proliferation of lymphoid cells of B cell

(70%) or T cell (30%) origin.

• The incidence of these tumours increases with age,

The current WHO classification stratifies according

to cell lineage (T or B cells) and incorporates clinical

features, histology, chromosomal abnormalities and

cell surface markers of the malignant cells.

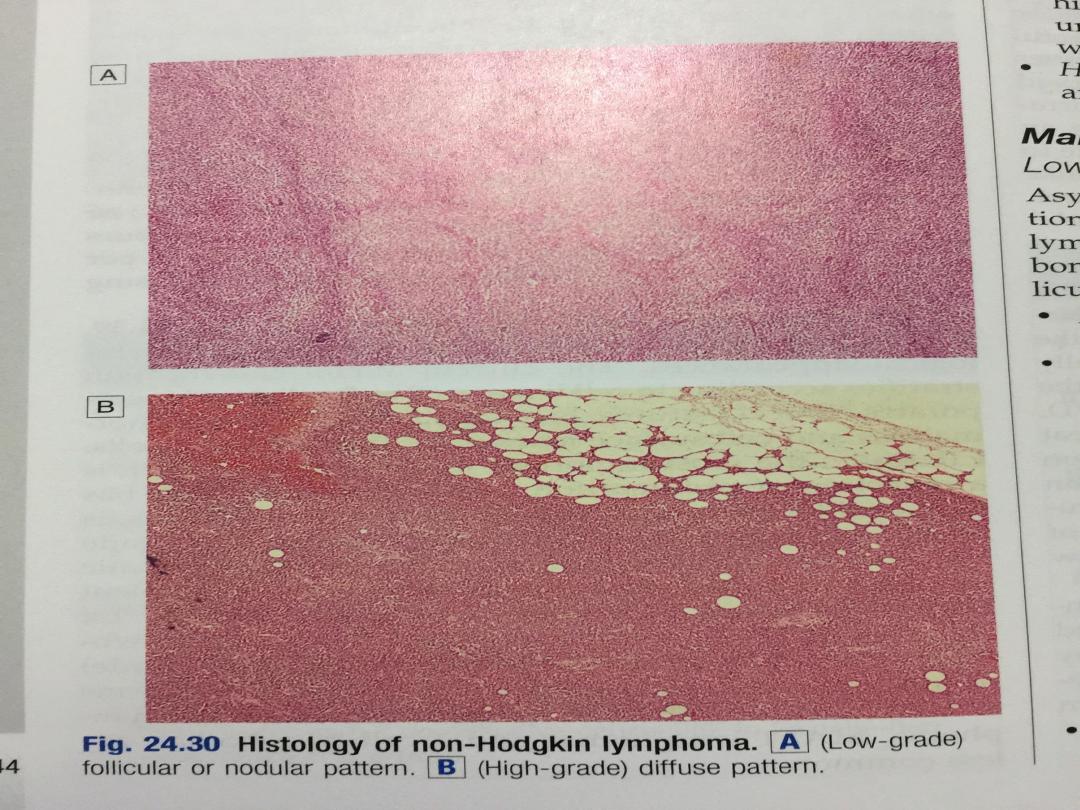

• Clinically, the most important factor is grade, which

is a reflection of proliferation rate. High-grade NHL

has high proliferation rates, rapidly produces

symptoms, is fatal if untreated, but is potentially

curable.

• Low-grade NHL has low proliferation rates, may

be asymptomatic for many months before

presentation, runs an indolent course, but is not

curable by conventional therapy.

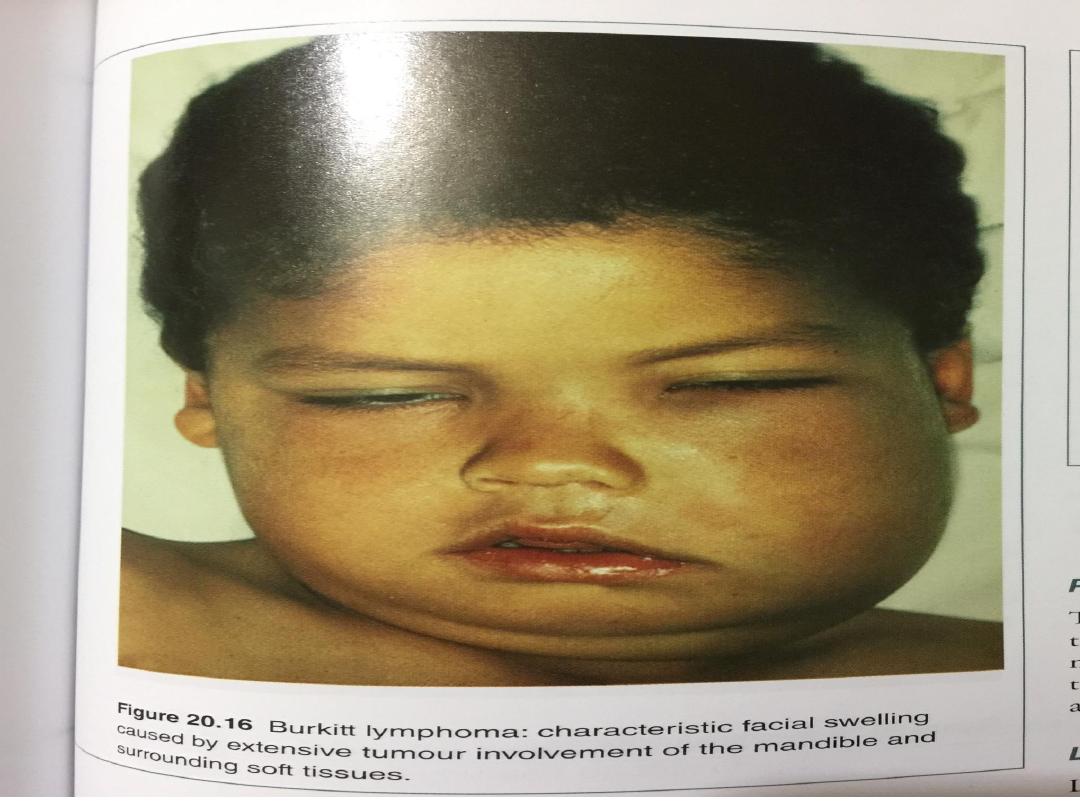

• Other forms of NHL, including Burkitt lymphoma,

mantle cell lymphoma, MALT lymphomas and T-

cell lymphomas, are less common.

• Of all cases of NHL in the developed world, over

twothirds are either diffuse large B-cell NHL (high-

grade) or follicular NHL (low-grade)

• Other forms of NHL, including Burkitt lymphoma,

mantle cell lymphoma, MALT lymphomas and T-cell

lymphomas, are less common.

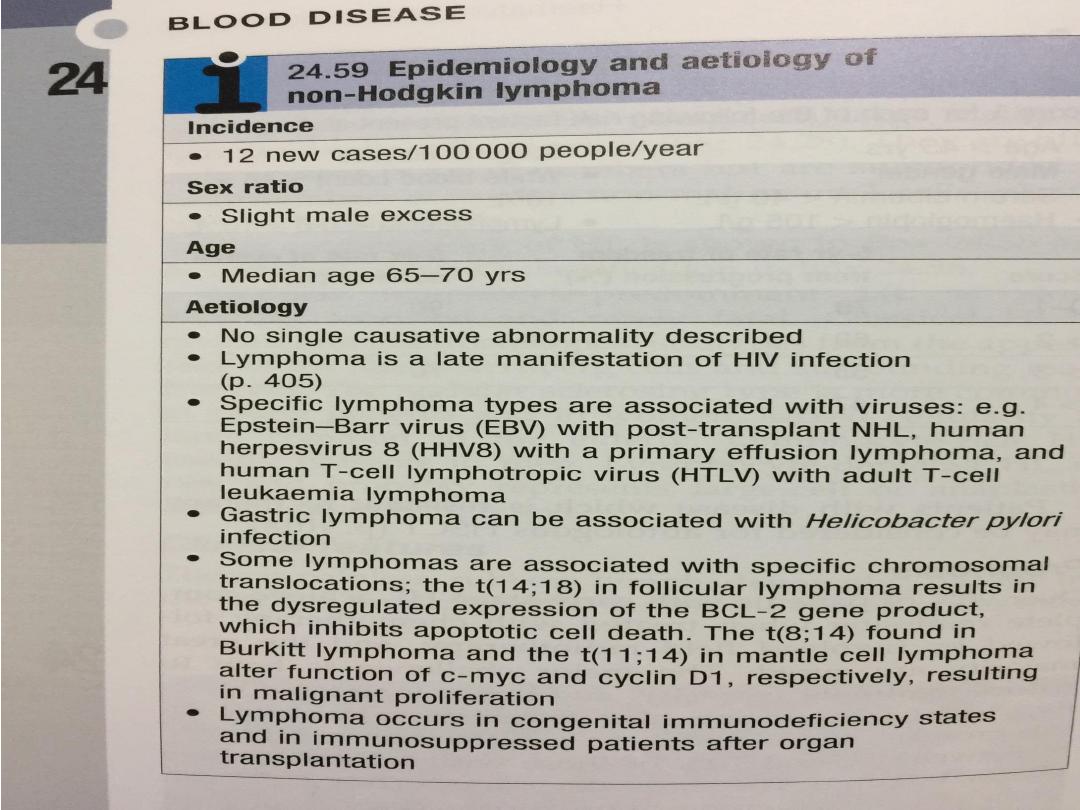

• Epidemiology of non-Hodgkin

lymphoma

• Incidence 12 new cases/100 000

people/year

• Sex ratio Slight male excess

• Age Median age 65–70 yrs

Aetiology

• No single causative abnormality described

• Lymphoma is a late manifestation of HIV infection

• Specific lymphoma types are associated with

viruses: e.g. Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) with post-

transplant NHL, human herpesvirus 8 (HHV8) with a

primary effusion lymphoma, and human T-cell

lymphotropic virus (HTLV) with adult T-cell

leukaemia lymphoma

• Gastric lymphoma can be associated with

Helicobacter pylori infection

• Some lymphomas are associated with specific

chromosomal translocations; the t(14;18) in

follicular lymphoma The t(8;14) found in Burkitt

lymphoma and the t(11;14) in mantle cell

lymphoma , resulting in malignant proliferation

• Lymphoma occurs in congenital immunodeficiency

states and in immunosuppressed patients after

organ transplantation

Clinical features

• Unlike Hodgkin lymphoma, NHL is often widely

disseminated at presentation, including in

extranodal sites.

• Patients present with lymph node enlargement,

which may be associated with systemic upset:

weight loss, sweats, fever and itching.

Hepatosplenomegaly may be present

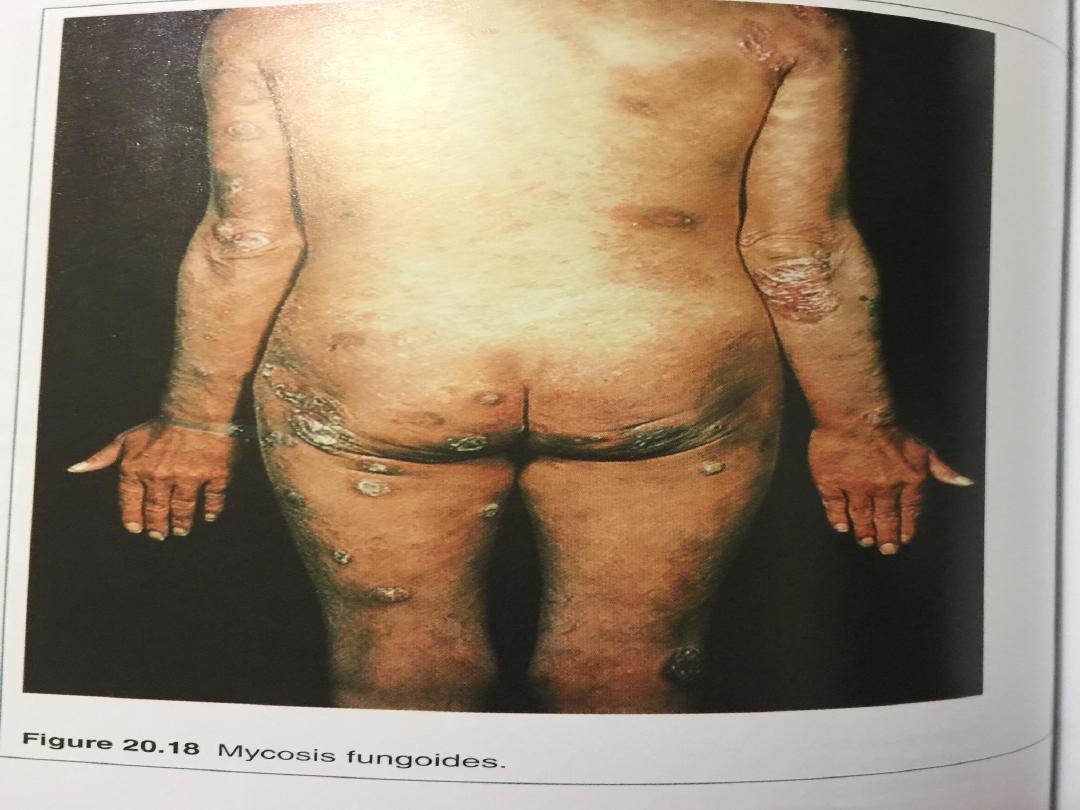

• Sites of extranodal involvement include the bone

marrow, gut, thyroid, lung, skin, testis, brain and,

more rarely, bone.

• Bone marrow involvement is more common in low-

grade (50–60%) than high-grade (10%) disease.

• Compression syndromes may occur, including gut

obstruction, ascites, superior vena cava obstruction

and spinal cord compression

• The same staging system is used for both HL and

NHL, but NHL is more likely to be stage III or IV at

presentation.

Investigations

• These are as for HL, but in addition the following

should be performed:

•

Bone marrow aspiration and trephine

.

• Immunophenotyping of surface antigens to distinguish

T from B cell tumours. This may be done on blood,

marrow or nodal material.

• Cytogenetic analysis to detect chromosomal

translocations and molecular testing for T cell receptor

immunoglobulin gene rearrangements, if available

• Immunoglobulin determination. Some lymphomas are

associated with IgG or IgM paraproteins, which serve as

markers for treatment response.

•

Measurement of uric acid levels

. Some very

aggressive high-grade NHLs are associated with very

high urate levels, which can precipitate renal failure

when treatment is started.

• HIV testing. This may be appropriate if risk factors

are present

Management

Low-grade NHL

• Asymptomatic patients may not require therapy.

Indications for treatment include marked systemic

symptoms, lymphadenopathy causing discomfort or

disfigurement, bone marrow failure or compression

syndromes.

• In follicular lymphoma, the options are:

• Radiotherapy. This can be used for localised stage I

disease, which is rare.

• Chemotherapy. Most patients will respond to oral

therapy with chlorambucil, which is well tolerated

but not curative.

• Transplantation. Particular interest centres on the

role of high-dose chemotherapy and HSCT in

patients with relapsed disease.

High-grade NHL

•

Patients with diffuse large B-cell NHL need treatment at

initial presentation

•

Chemotherapy. The majority (> 90%) are treated with

intravenous combination chemotherapy, typically with the

CHOP regimen (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine

and prednisolone).

•

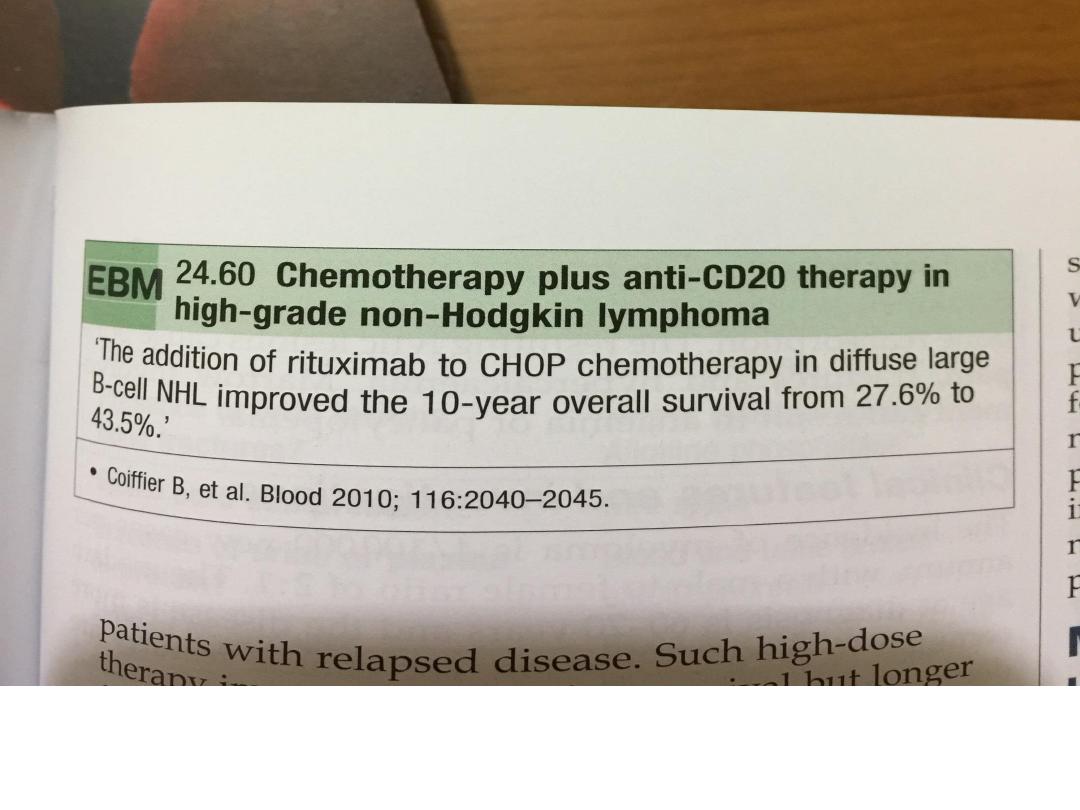

When combined with CHOP chemotherapy,

•

the biological therapy rituximab (R) increases the complete

response rates and improves overall survival.

•

R-CHOP is currently recommended as first-line therapy for

those with stage II or greater diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

•

Radiotherapy. A few stage I patients without bulky disease

may be suitable for radiotherapy

• Radiotherapy is also indicated for a residual

localised site of bulk disease after chemotherapy,

and for spinal cord and other compression

syndromes.

• HSCT. Autologous HSCT benefits patients with

relapsed chemosensitive disease

Prognosis

• Low-grade NHL runs an indolent remitting and

relapsing course, with an overall median survival of 10

years.

• Transformation to a high-grade NHL occurs in 3% per

annum and is associated with poor survival

• In diffuse large B-cell high-grade NHL treated with R-

CHOP, some 75% of patients overall respond initially to

therapy and 50% will have disease-free survival at 5

years.

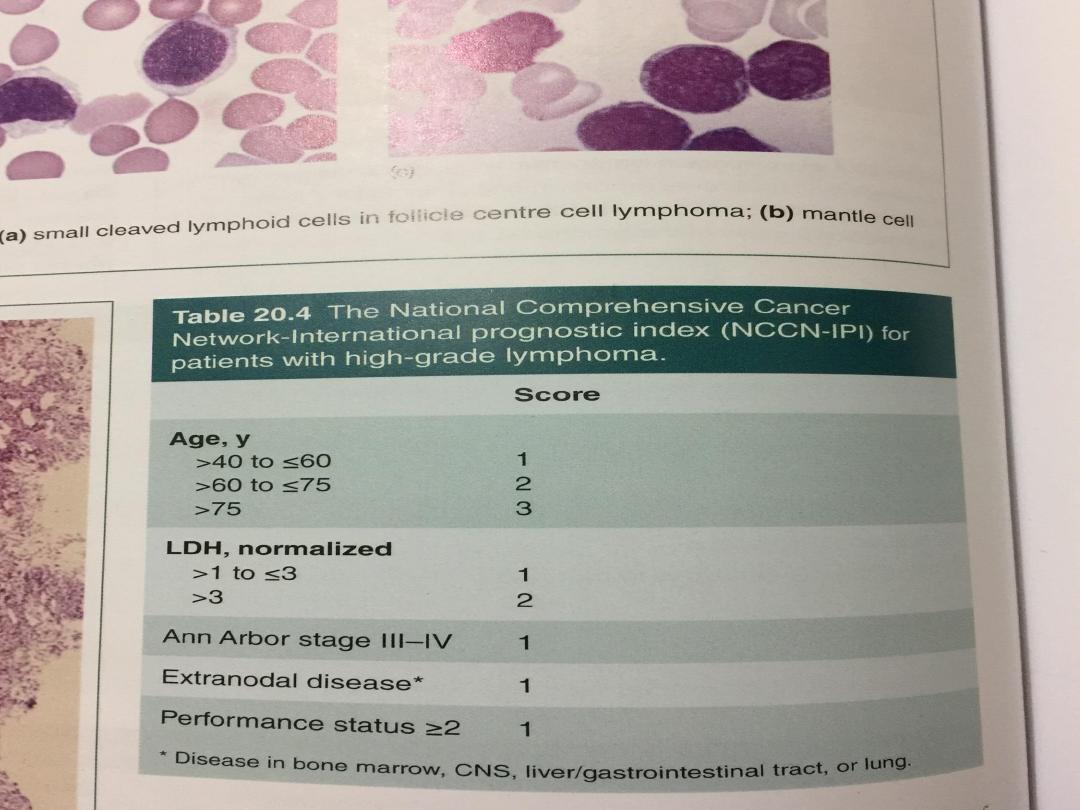

• For high-grade NHL, 5-year survival ranges from 75% in

those with low-risk scores (age < 60 years, stage I or II,

one or fewer extranodal sites, normal LDH and good

performance status)

• to 25% in those with high-risk scores (increasing

age, advanced stage, concomitant disease and a

raised LDH).

• Relapse is associated with a poor response to

further chemotherapy (< 10% 5-year survival), but

in patients under 65 years, HSCT improves survival