Overview of Viral infections Micro. Dr. Mohammed

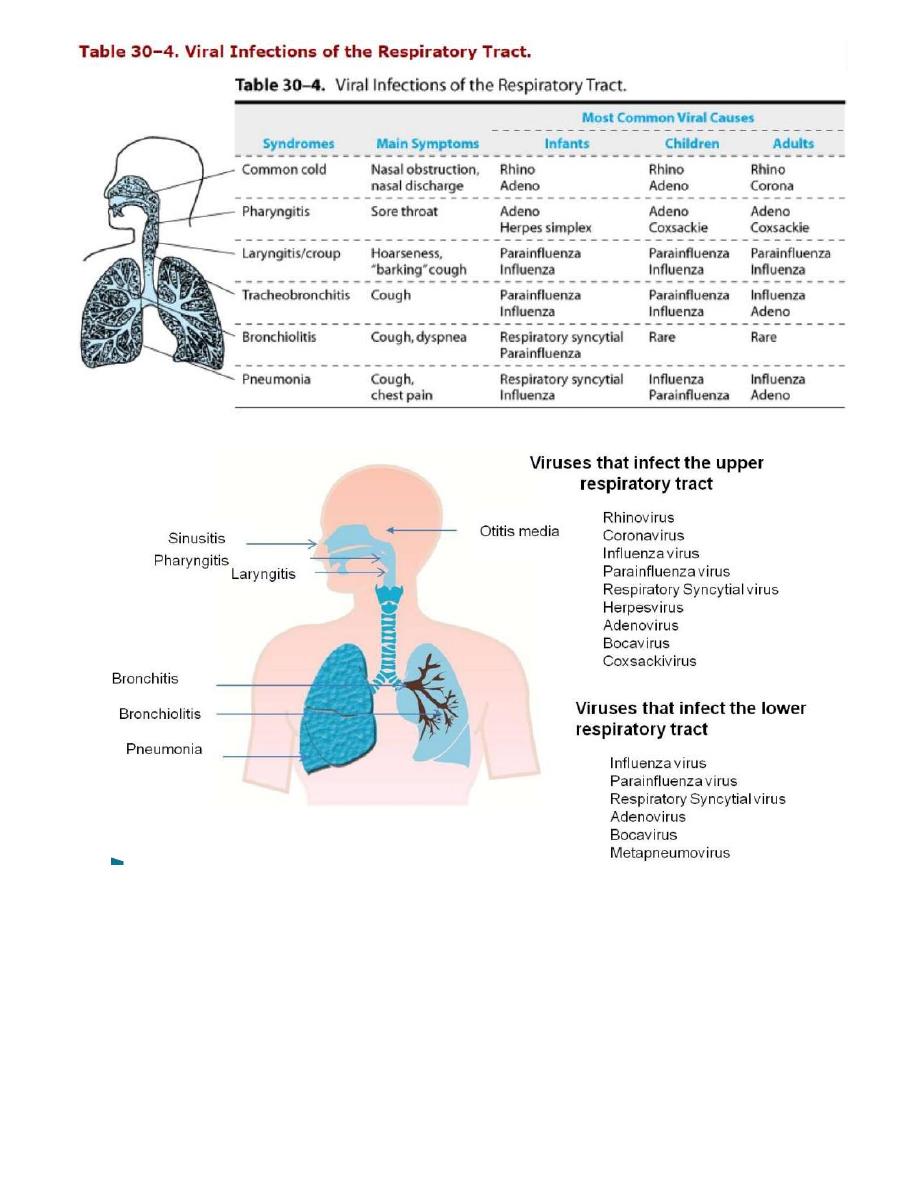

Overview of Acute Viral Respiratory Infections

viruses gain access to the human body primarily in the form of aerosolized droplets or saliva,

despite normal host protective mechanisms, including

• the mucous covering most surfaces,

• ciliary action,

• collections of lymphoid cells,

• alveolar macrophages,

• secretory IgA.

Many infections remain localized in the respiratory tract, although some viruses produce systemic

spread (eg, chickenpox, measles, rubella).

The symptoms depend on whether the infection is concentrated in the upper or lower respiratory

tract.

Definitive diagnosis requires

•isolation of the virus,

•identification of viral gene sequences,

•demonstration of a rise in antibody titer,

the specific viral disease can frequently be deduced by considering the major symptoms, the

patient's age, the time of year, and any pattern of illness in the population.

The severity can range from inapparent to overwhelming. The most severe illness is usually seen

in infants (paramyxoviruses) and in elderly or chronically ill adults (influenza virus).

Overview of Viral Infections of the GIT

A few agents, such as herpes simplex virus and Epstein-Barr virus, probably infect cells in the

mouth. in the intestinal tract it exposed to harsh elements (acid, bile salts, and proteolytic

enzymes).

Consequently, viruses are all acid- and bile saltsresistant.

There may also be virus-specific secretory IgA and nonspecific inhibitors of viral replication to

overcome

Acute gastroenteritis is with symptoms ranging from mild, watery diarrhea to severe febrile illness

characterized by vomiting, diarrhea, and prostration. Rotaviruses, Norwalk viruses, and

caliciviruses are major causes of gastroenteritis.

Infants and children are affected most often.

Some enteric viruses utilize host proteases to facilitate infection (proteolytic digestion of viral

capsid that then facilitates events such as virus attachment or membrane fusion).

Enteroviruses, coronaviruses, and adenoviruses gastrointestinal infections are often

asymptomatic.

Some enteroviruses (polioviruses, and hepatitis A virus) are important causes of systemic disease

but do not produce intestinal symptoms.

Overview of Viral Skin Infections

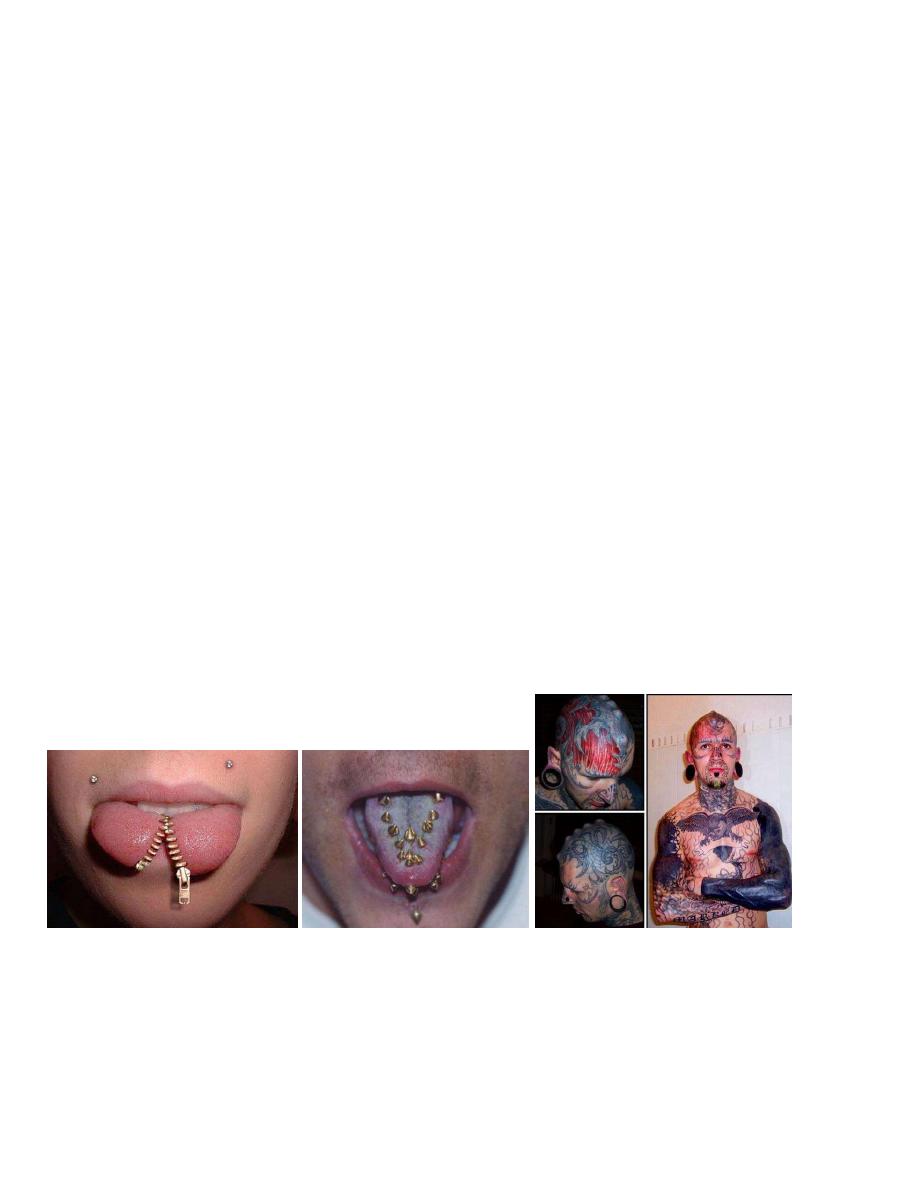

The skin is a tough and impermeable barrier to the entry of viruses. However, a few viruses are

able to breach this barrier and initiate infection of the host through:

• small abrasions of the skin (poxviruses, papillomaviruses, herpes simplex viruses),

• the bite of arthropod vectors (arboviruses)

• infected vertebrate hosts (rabies virus, herpes B virus),

• injected during blood transfusions or via contaminated needles, such as acupuncture and

tattooing (hepatitis B virus, HIV).

Some agents produce localized lesions (papillomaviruses and molluscum contagiosum); most

spread to other sites.

The epidermal layer is devoid of blood vessels and nerve fibers, so viruses that infect epidermal

cells tend to stay localized.

Viruses introduced deeper into the dermis reach blood vessels, lymphatics, dendritic cells, and

macrophages and usually spread and cause systemic infections.

Such infections originate by another route (eg, measles virus infections occur via the respiratory

tract), and the skin becomes infected from below.

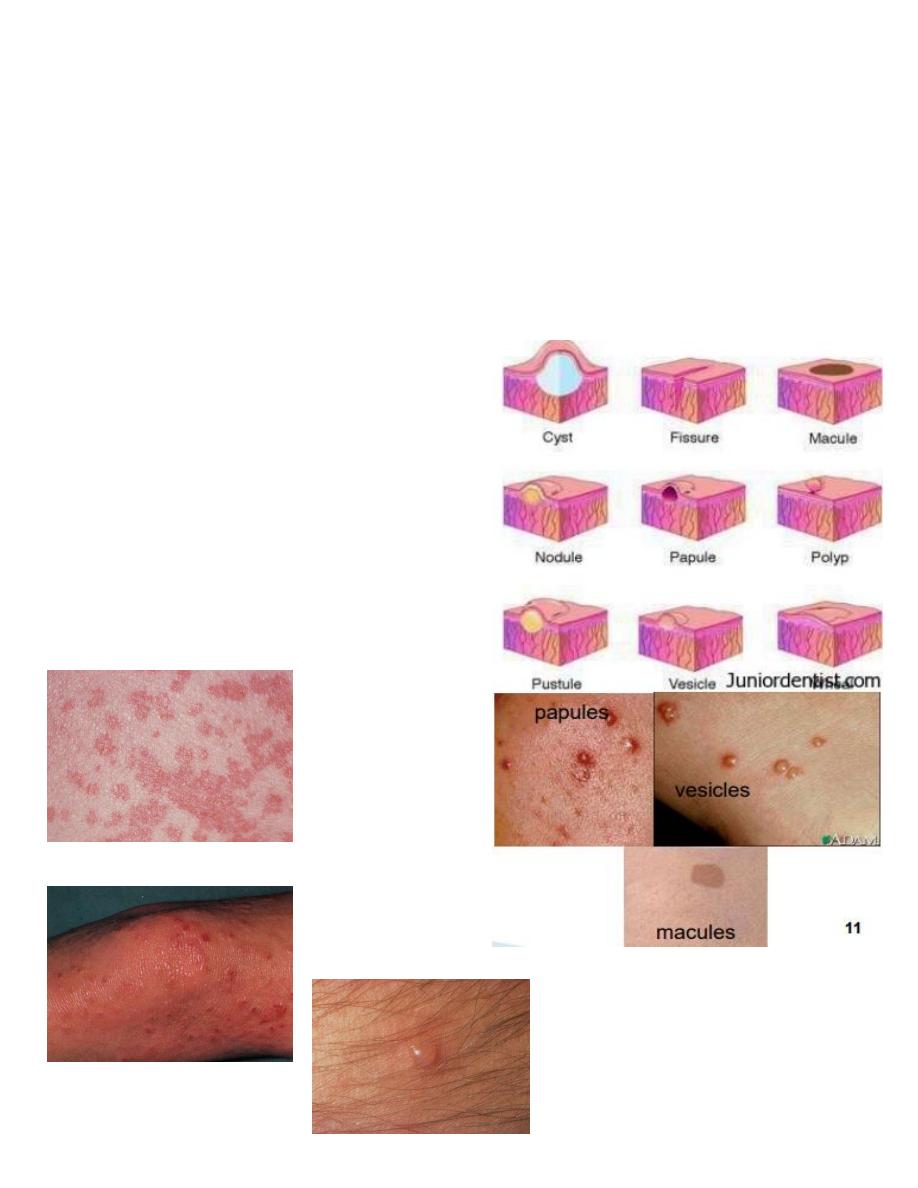

Lesions in skin rashes are designated as macules,

papules, vesicles, or pustules.

Macules, which are caused by local dilation of

dermal blood vessels, papules if edema and

cellular infiltration are present in the area.

Vesicles occur if the epidermis is involved, and

they become pustules if an inflammatory

reaction

delivers

polymorpho-nuclear

leukocytes to the lesion. Ulceration and scabbing

follow. Hemorrhagic and petechial rashes occur

when there is more severe involvement of the

dermal vessels.

Infectious virus is not shed from the maculopapular rash of measles or from rashes associated with

arbovirus infections.

In contrast, skin lesions are important in the spread of poxviruses and herpes simplex viruses (high

titers in the fluid of these vesiculopustular rashes, and they are able to initiate infection by

direct contact with other hosts).

Overview of Viral Infections of the CNS

viral infection of CNS is always a serious matter. Viruses can gain access to the brain by two routes:

• by the bloodstream (hematogenous spread)

• by peripheral nerve fibers (neuronal spread).

blood spreading may occur by:

• through endothelium of small cerebral vessels,

• passive transport across the vascular endothelium,

• through the choroid plexus to the cerebrospinal fluid,

• transport within infected monocytes, leukocytes, or lymphocytes.

Once the blood-brain barrier is breached, more extensive spread throughout the brain and spinal

cord is possible.

via peripheral nerves.

Virions can be taken up at sensory nerve or motor endings and be moved within axons, through

endoneural spaces, or by Schwann cell infections.

Herpes viruses travel in axons to be delivered to dorsal root ganglia neurons.

The virus may utilize more than one routes of spread.

Many viruses, including herpes-, toga-, flavi-, entero-, rhabdo-, paramyxo-, and bunyaviruses,

can infect the central nervous system and cause meningitis, encephalitis, or both.

Encephalitis caused by herpes simplex virus is the most common cause of sporadic encephalitis in

humans.

Pathologic reactions to cytocidal viral infections of the central nervous system include necrosis,

inflammation, and phagocytosis by glial cells.

The postinfectious encephalitis (after measles infections after rubella infections) is characterized by

demyelination without neuronal degeneration and is probably an autoimmune disease.

The neurodegenerative disorders, called slow virus infections, are uniformly fatal. Features of these

infections include a long incubation period (months to years) followed by the onset of clinical illness

and progressive deterioration, resulting in death in weeks to months; usually only the central nervous

system is involved. Some slow virus infections, such as progressive multifocal leuko-

encephalopathy (JC (John Cunningham) polyomavirus) and subacute sclerosing

panencephalitis (measles virus), are caused by typical viruses.

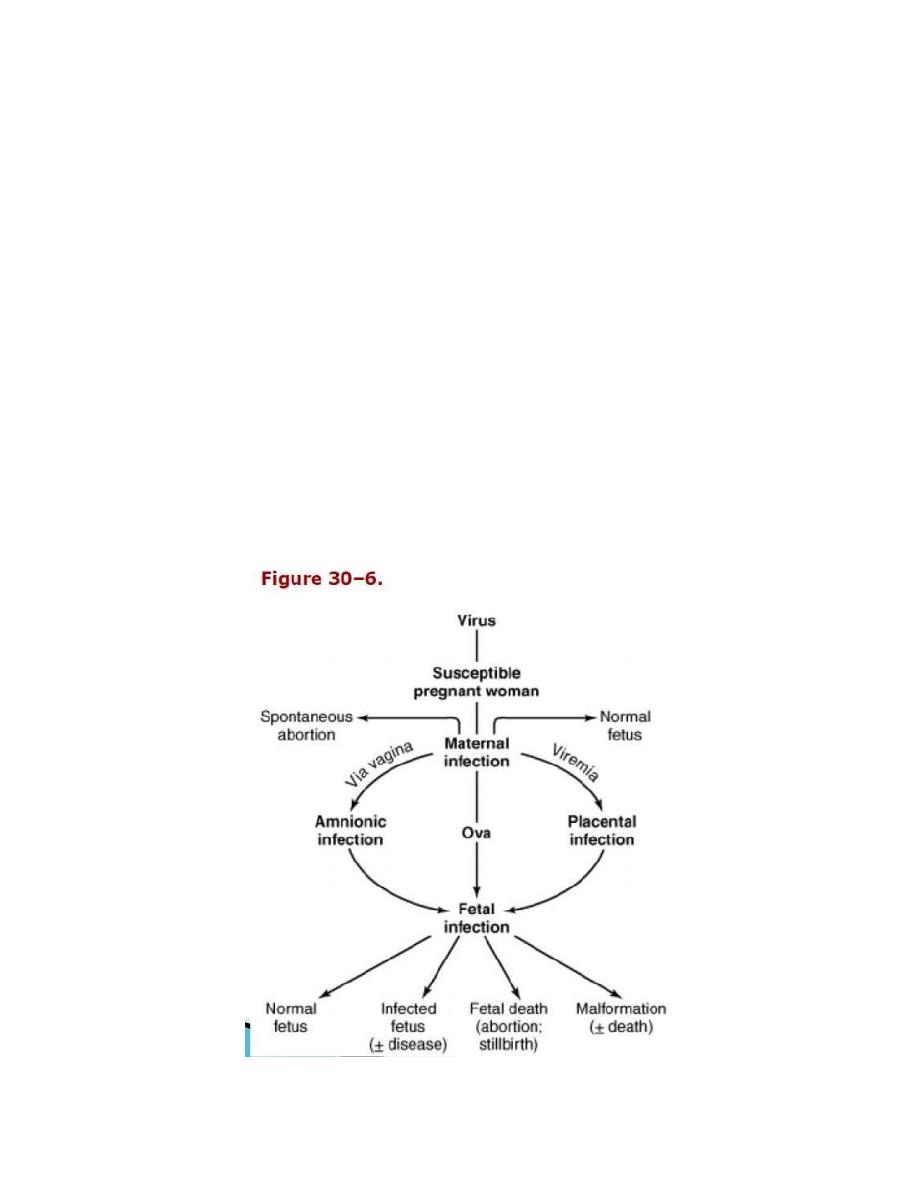

Overview of Congenital Viral Infections

Viral diseases produce in the human fetus. Most maternal viral infections do not result in viremia

and fetal involvement. if so, serious damage may be done to the fetus.

Three principals involved in the production of congenital defects are:

(1) the ability of the virus to infect the pregnant woman and be transmitted to the fetus;

(2) the stage of gestation at which infection occurs;

(3) the ability of the virus to cause damage to the fetus directly, or indirectly, by infection of

the mother resulting in an altered fetal environment (eg, fever). The sequence of events that

may occur prior to and following viral invasion of the fetus

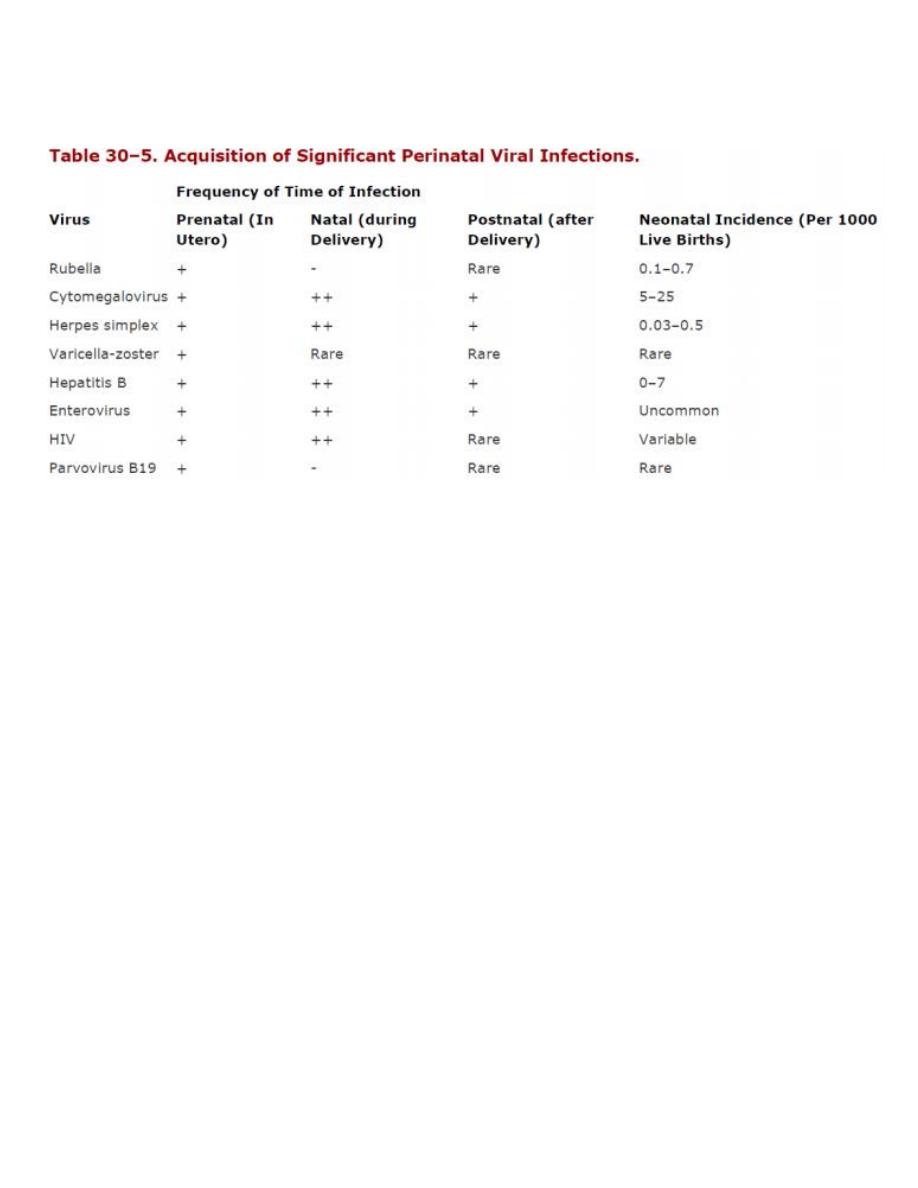

primary agents responsible for congenital defects (Rubella virus and cytomegalovirus). Or can

occur by (herpes simplex, varicella-zoster, hepatitis B, measles, and mumps virus and with

HIV, parvovirus, and some enteroviruses) (Table 30–5).

In utero infections may result (fetal death, premature birth, intrauterine growth retardation, or

persistent postnatal infection).

Developmental malformations (congenital heart defects, cataracts, deafness, microcephaly, and

limb hypoplasia.

Fetal tissue is rapidly proliferating. Viral infection and multiplication may destroy cells or alter cell

function.

Lytic viruses, such as herpes simplex, may result in fetal death. Less cytolytic viruses, such as

rubella, may slow the rate of cell division. If this occurs during a critical phase in organ

development, structural defects and congenital anomalies may result.

Viral infections may be transmitted from the mother during delivery (natal) from contaminated

genital secretions, stool, or blood. Less commonly, infections may be acquired during the first few

weeks after birth (postnatal) from maternal sources, family members, hospital personnel, or blood

transfusions.

Effect of Host Age

Host age is a factor in viral pathogenicity. More severe disease is often produced in newborns. In

addition to maturation of the immune response with age, there seem to be age-related changes in

the susceptibility of certain cell types to viral infection. Viral infections usually can occur in all age

groups but may have their major impact at different times of life. Examples include rubella, which

is most serious during gestation; rotavirus, which is most serious for infants; and St. Louis

encephalitis, which is most serious in the elderly.