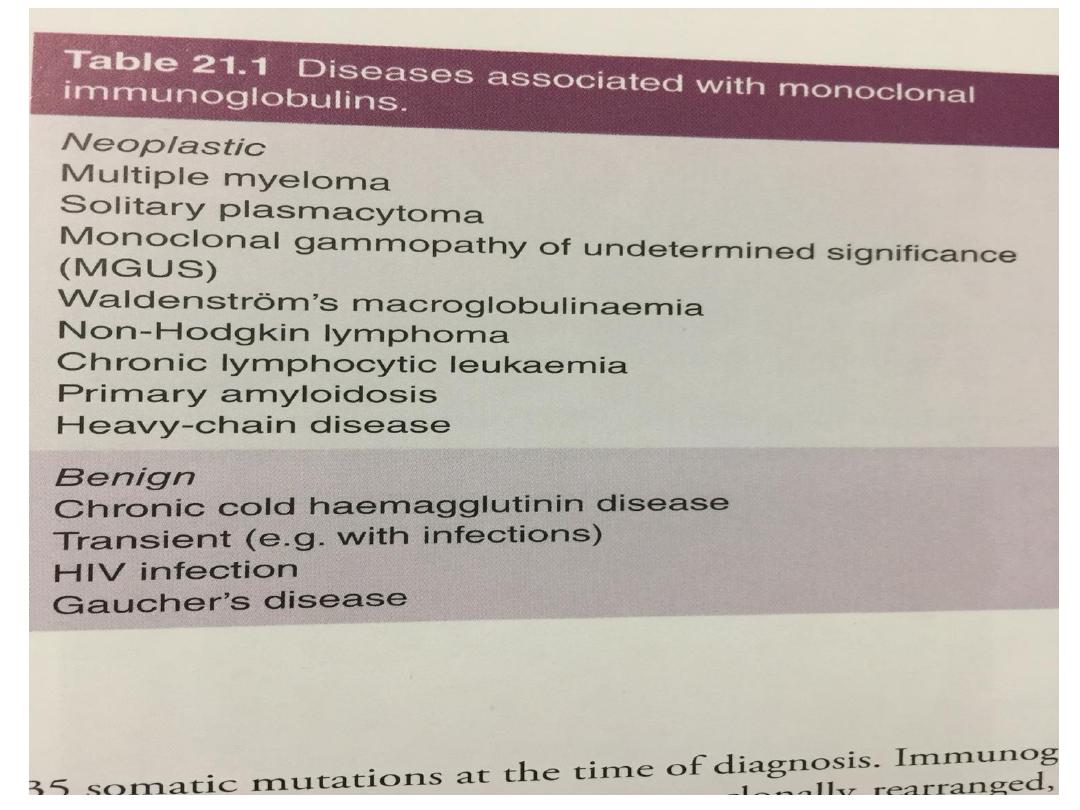

Multiple myloma

Multiple myeloma

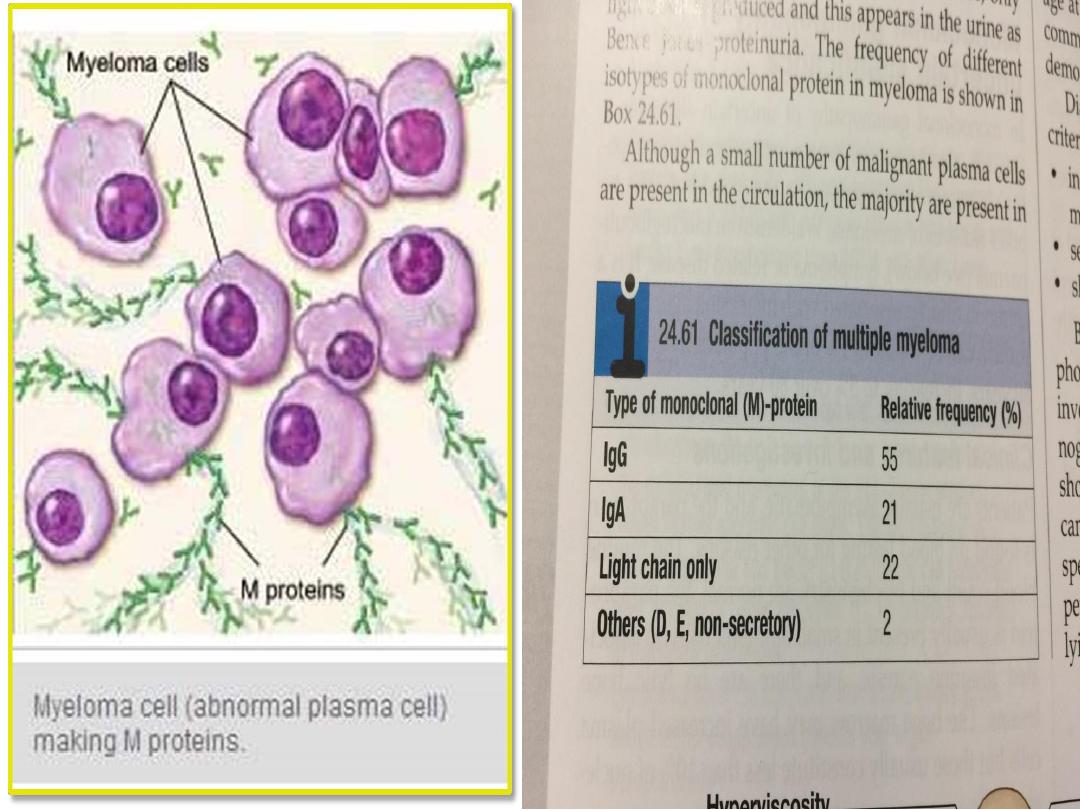

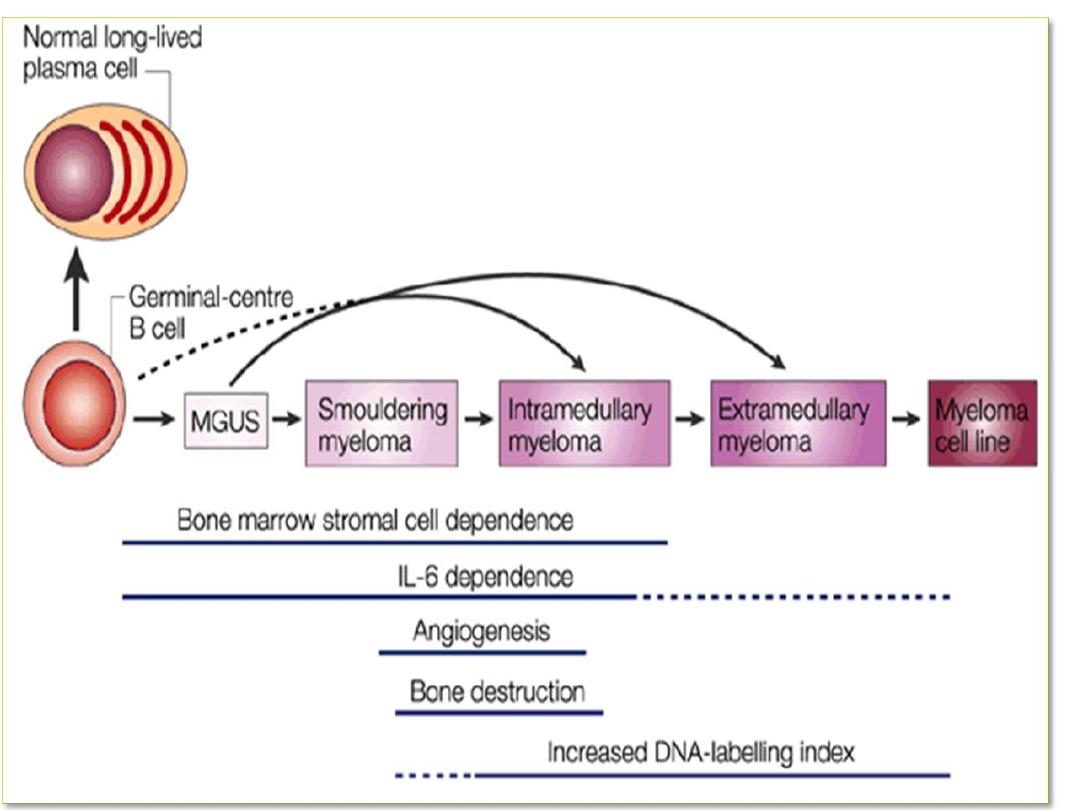

• This is a malignant proliferation of plasma cells.

Normal plasma cells are derived from B cells and

produce immunoglobulins which contain heavy and

light chains.

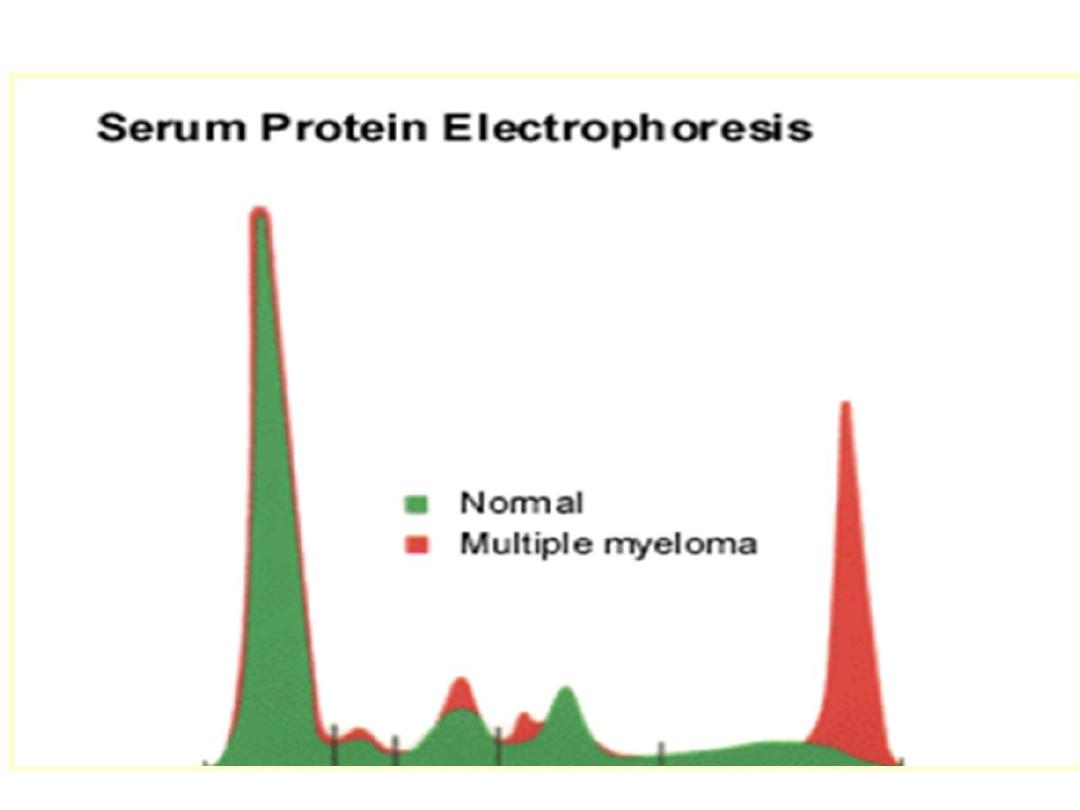

• Normal immunoglobulins are polyclonal, which

means that a variety of heavy chains are produced

and each may be of kappa or lambda light chain

type

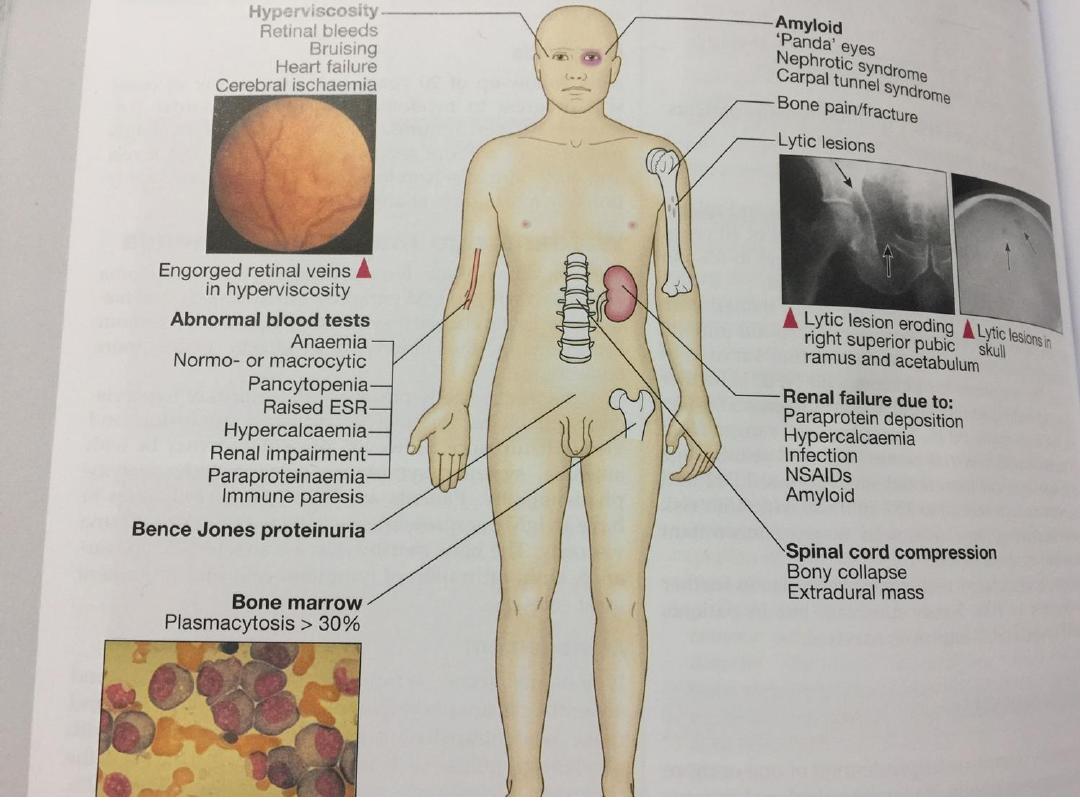

• In some cases, only light chain is produced and this

appears in the urine as Bence Jones proteinuria.

• The malignant plasma cells produce cytokines,

which stimulate osteoclasts and result in net bone

reabsorption.

• The resulting lytic lesions cause bone pain, fractures

and hypercalcaemia.

• Marrow involvement can result in anaemia or

pancytopenia.

Clinical features and investigations

• The incidence of myeloma is 4/100 000 new cases

per annum, with a male to female ratio of 2 : 1

• The median age at diagnosis is 60–70 years and the

disease is more common in Afro-Caribbeans.

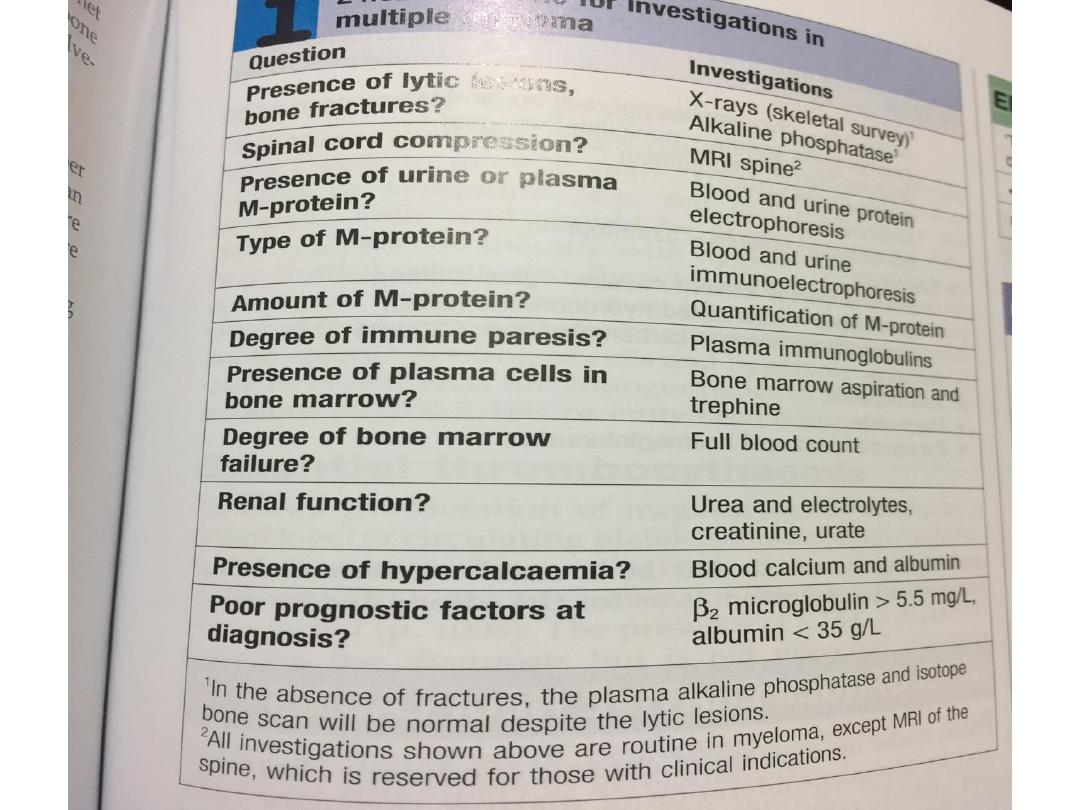

Diagnosis of myeloma requires two of the following

criteria:

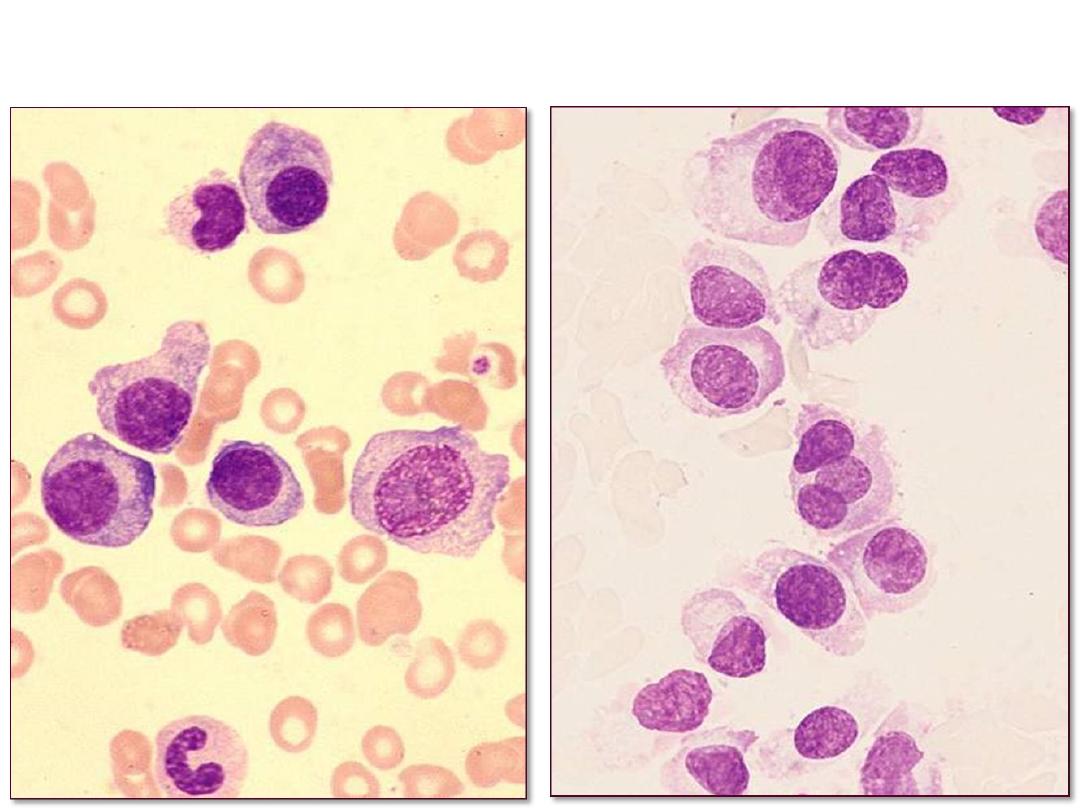

1. increased malignant plasma cells in the bone

marrow

2. serum and/or urinary M-protein

3. skeletal lytic lesions.

• Bone marrow aspiration, plasma and urinary

electrophoresis, and a skeletal survey are thus

required.

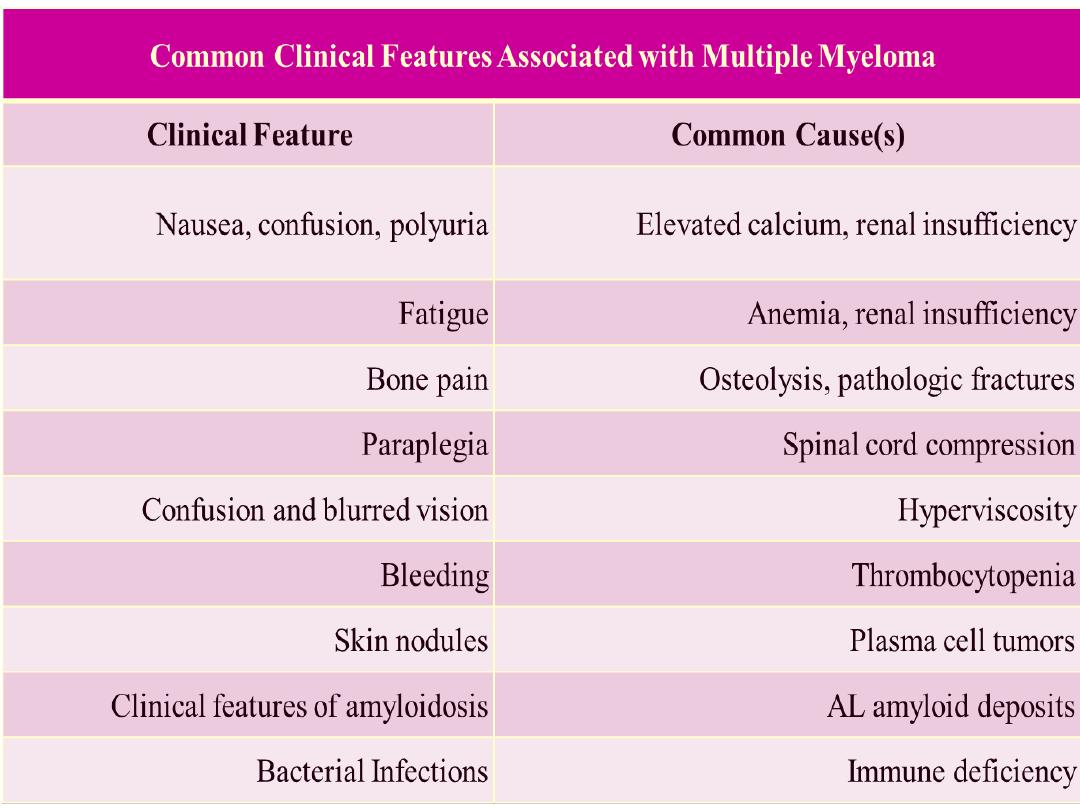

• The presentation of MM can range from asymptomatic

to severely symptomatic, with complications requiring

emergent treatment.

• Systemic elements include bleeding, infection, and

renal failure; pathologic fractures and spinal cord

compression may occur.

• The acronym CRAB emphasizes the most useful clinical

and laboratory features of symptomatic multiple

myeloma: elevated Calcium, Renal insufficiency,

Anemia, and Bone lesions. The clinical features of

multiple myeloma are inconsistent, however, and mild,

early symptoms can mimic many other diseases Bone

pain, which is reported by about 60% of patients at the

time of diagnosis, is the symptom that most

immediately focuses clinicians’ attention on multiple

myeloma. On the other hand, in a population that is

typically in the late 50’s or older at disease onset, bone

pain is also a common and nonspecific finding.

Clinical signs and presenting symptoms

• Musculoskeletal examination:

1. Bony tenderness

2. pain without tenderness

• Neurologic assessment:

1. Sensory level change (ie, loss of sensation below a

dermatome corresponding to a spinal cord

compression)

2. Neuropathy.

3. Myopathy, positive Tinel sign, or positive Phalen

sign .

• Dermatologic evaluation:

1. Pallor from anemia,

2. Ecchymosis,

3. Purpura from thrombocytopenia,

• Extramedullary plasmacytomas (most commonly in

aero digestive tract but also orbital, ear canal,

cutaneous, gastric, rectal, prostatic, retroperitoneal

areas)

Clinical signs and presenting symptoms

• Abdominal examination: Hepatosplenomegaly

• Cardiovascular evaluation: Cardiomegaly

• Bone Marrow Aspiration

Recommended laboratory tests for diagnosis,

prognosis and risk stratification

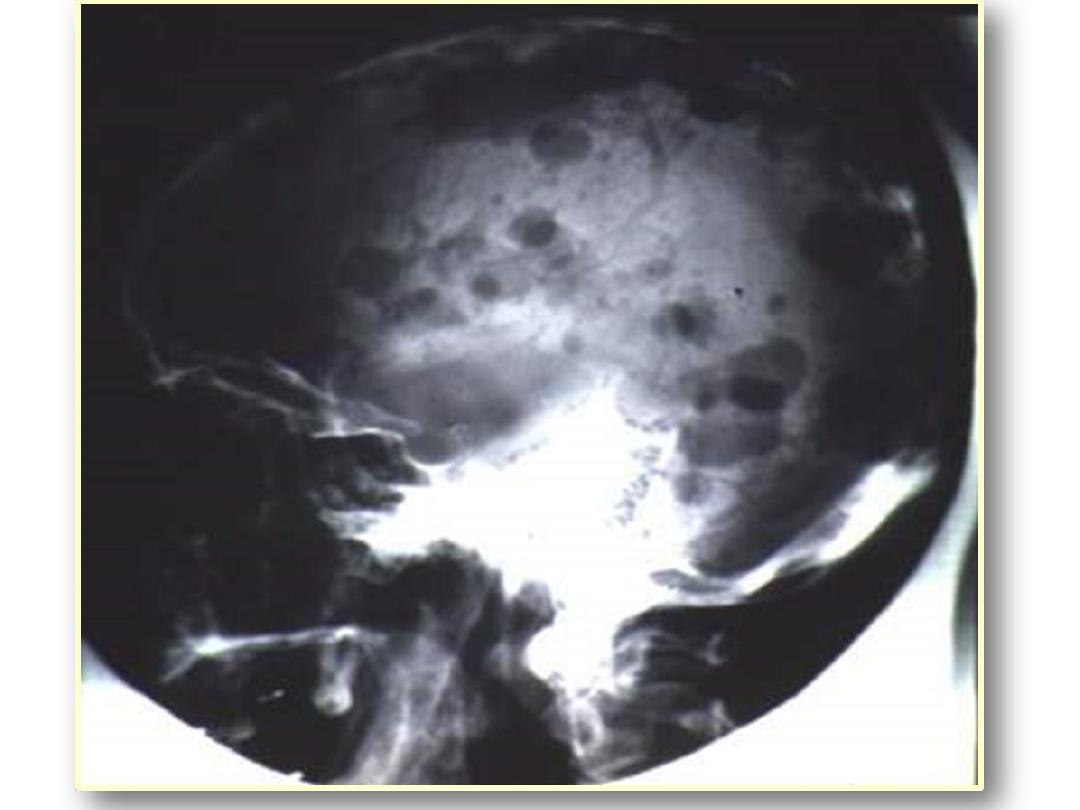

2. Imaging modalities

• Radiological skeletal bone survey, including spine,

pelvis, skull, humeral and femurs is necessary.

• Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computerized

tomography (CT) scan may be needed to evaluate

symptomatic bony sites

• A skull X-ray shows the classic 'punched-out' lytic

bone lesions. Although the skull lesions are

asymptomatic, extensive vertebral involvement

causes compression fractures, resulting in pain and

loss of height (5 cm on average by the time of

diagnosis).

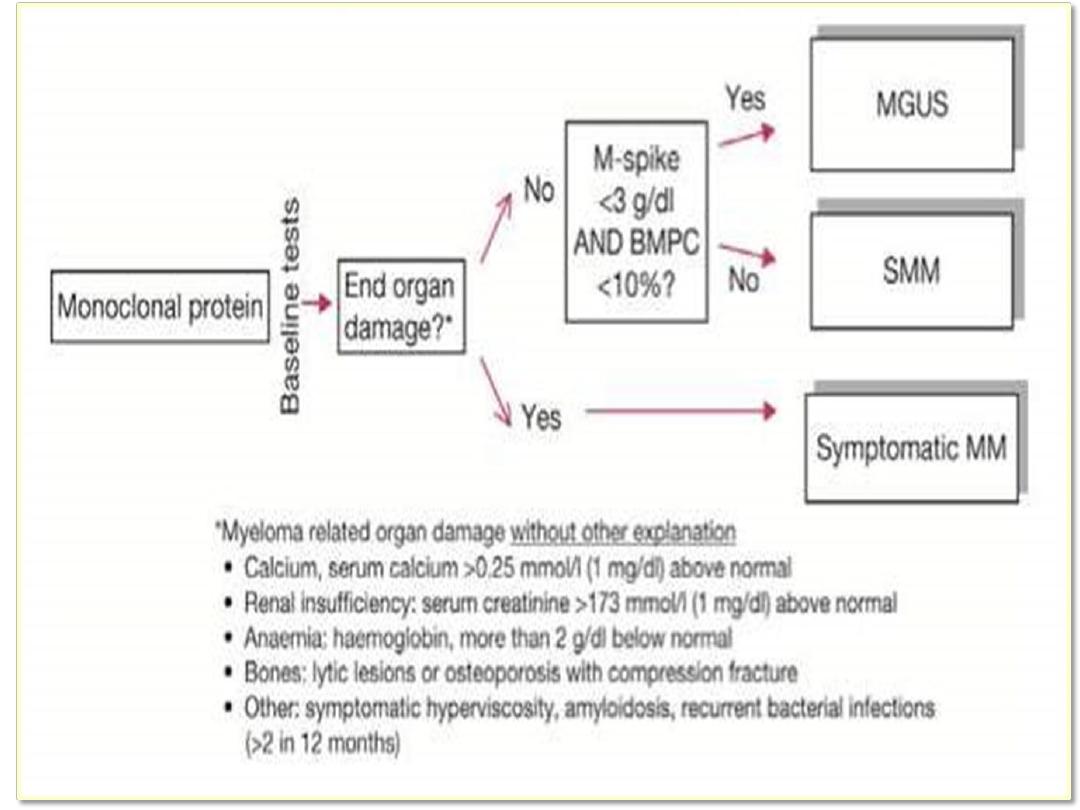

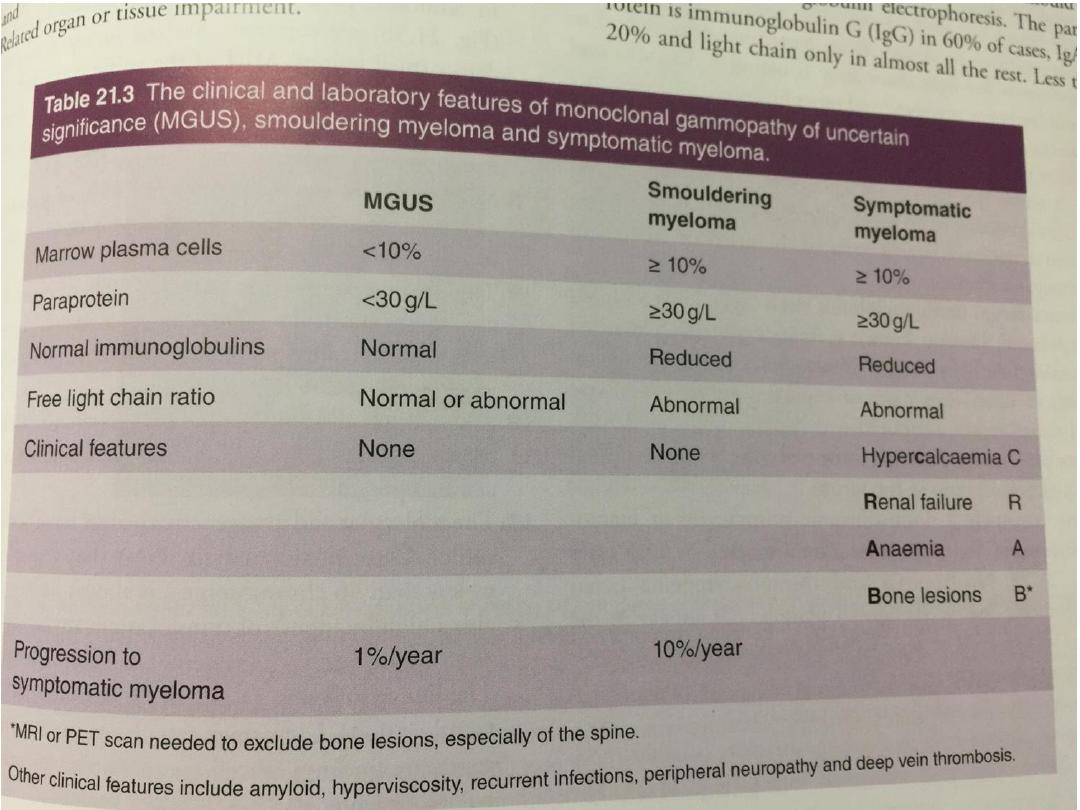

Classification

• It’s important to differentiate between MM and MGUS:

• MGUS:

1. Intact immunoglobulino3 g/100 ml

2. Less than10% bone marrow plasma cells

3. Absence of end organ damage

Classification

• The diagnosis of myeloma requires:

1. 10% or more clonal plasma cells on bone marrow

examination or a biopsy proven plasmacytoma.

2. Evidence of end-organ damage

3. Presence of 60% or more clonal plasma cells in the

marrow should also be considered as myeloma

regardless of the presence or absence of end-organ

damage

• Evidence of end-organ damage

(CRAB):Hypercalcemia ,Renal failure,Anemia,Bone

lesions.

• These lesions are related to a plasma cell

proliferative disorder and not explained by another

unrelated disease or disorder.

• Smoldering multiple myeloma (also referred to

asymptomatic multiple myeloma)

• Both criteria must be met:

1. Serum monoclonal protein (IgG or IgA) 3 g/dl

2. (and/or) Clonal bone marrow plasma cells 10%-

60%.

3. And absence of end-organ damage .

Management

• If patients are asymptomatic with no evidence of

end organ damage (e.g. to kidneys, bone marrow or

bone), treatment may not be required.

• Immediate support

• High fluid intake to treat renal impairment and

hypercalcaemia

• Analgesia for bone pain.

• Bisphosphonates for hypercalcaemia and to delay

other skeletal related events

• Allopurinol to prevent urate nephropathy.

• Plasmapheresis, if necessary, for hyperviscosity.

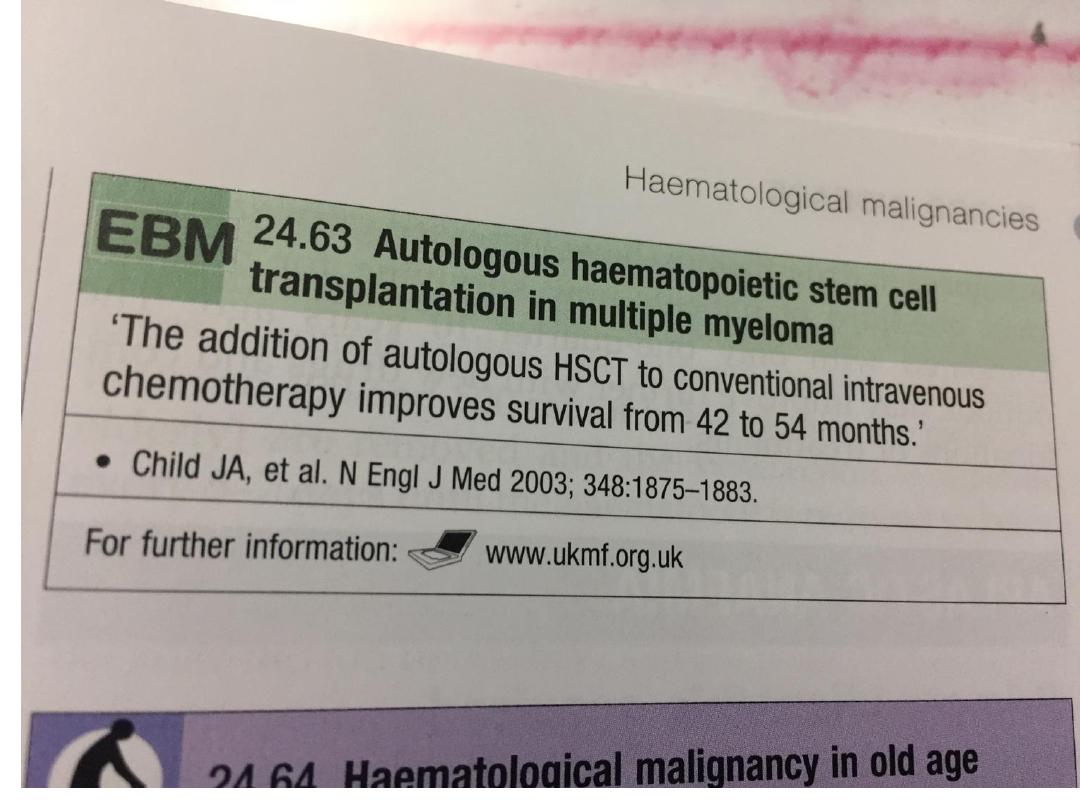

Chemotherapy with or wthout HSCT

• Myeloma therapy has improved with the addition

of novel agents, initially thalidomide and more

recently the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib,

• In younger, fitter patients, standard treatment

includes first-line chemotherapy to maximum

response and then an autologous HSCT,

• Radiotherapy This is effective for localised bone

pain not responding to simple analgesia and for

pathological fractures.

• It is also useful for the emergency treatment of

spinal cord compression complicating extradural

plasmacytomas

• Bisphosphonates Long-term bisphosphonate

therapy reduces bone pain and skeletal events.

These drugs protect bone and may cause apoptosis

of malignant plasma cells.

• There is evidence that intravenous zoledronate in

combination with anti-myeloma therapy confers a

survival advantage over oral bisphosphonates.

• Osteonecrosis of the jaw may be associated with

long-term use; therefore regular dental review is

advisable.

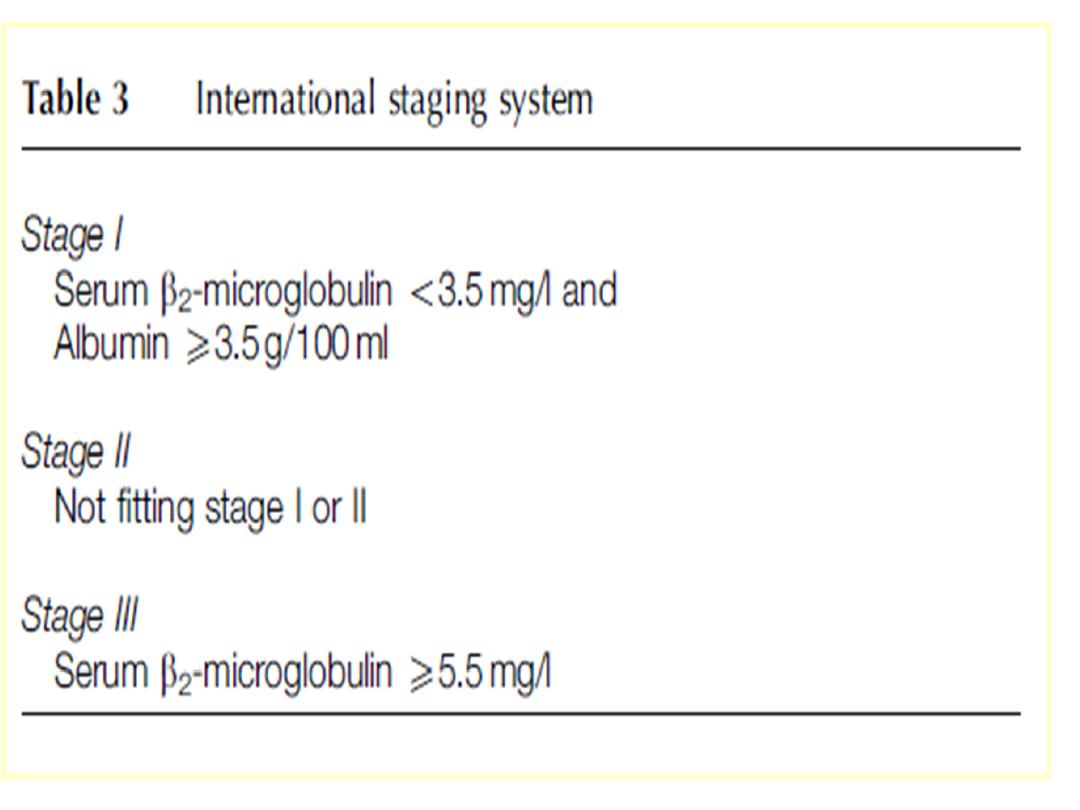

Prognosis

• The international staging system (ISS) identifies

poor prognostic features, including a high β2-

microglobulin and low albumin at diagnosis (ISS

stage 3, median survival 29 months).

• Those with a normal albumin and a low β2-

microglobulin (ISS stage 1) have a median survival

of 62 months.