Infectious emergency

Done by : KAWTHER SALIMSepsis;

Sepsis is a heterogeneous syndrome characterized by widespread inflammation and potential organ harm initiated by a microorganism.Although gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria account for the majority of cases, fungi, viruses, mycobacteria,, and protozoans can trigger sepsis. Invasion of the blood is not necessary to develop or identify sepsis, which is determined by the host response to the infectious insult. As sepsis severity increases, a multifactorial series of events lead to impairments in oxygen delivery, secondary to macro- and microvascular mal perfusion, as well as direct cellular damage secondary to inflammation. Eventually, multisystem organ failure occurs, and mortality is high.

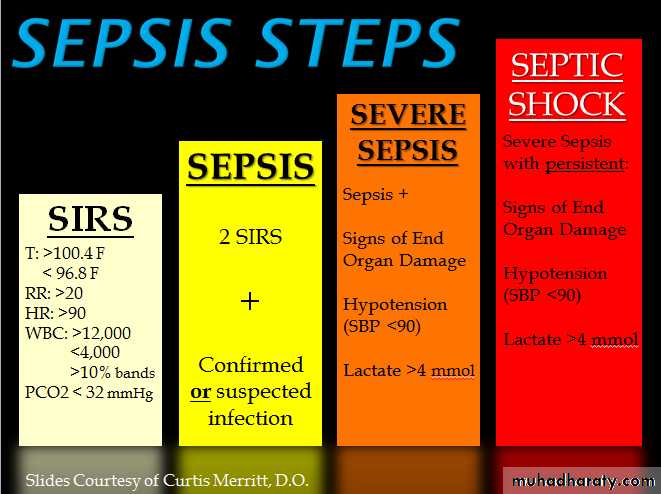

Definitions;

Sepsis: is defined as suspected or confirmed infection with evidence of systemic inflammation response syndrome (demonstrated either through evidence of the systemic immune response syndrome or laboratorySever sepsis :defined as sepsis plus evidence of new organ dysfunction thought to be secondary to tissue hypoperfusion.

Septic shock: exists when cardiovascular failure occurs, evidenced as persistent hypotension or need for vasopressors despite adequate fluid resuscitation; this latter category has a particularly poor prognosis.

Systemic inflammatory response syndrome

criteria:1. Fever (temperature >38.3°C) or hypothermia (temperature <36°C)

2. Pulse rate (>90 beats/min or >2 SDs above the normal value for age)

3. Tachypnea (respiratory rate >20 breaths/min)

4. Leukocytosis (WBC >12,000 cells/μL) or leukopenia (WBC <4000 cells/μL), or normal WBC with >10% immature forms

Severe Sepsis: Sepsis-induced tissue hypo perfusion or organ dysfunction

(any of the following thought to be due to infection)

• Sepsis-induced hypotension

• Lactate level above upper limits of laboratory normal levels• Urine output <0.5 mL/kg per hour for at least 2 h despite adequate fluid

• resuscitation

• Acute lung injury with PaO2/FIO2 <250 in the absence of pneumonia as

• infectious source

• Acute lung injury with PaO2/FIO2 <200 in the absence of pneumonia as

• infectious source

• Creatinine level >2.0 milligrams/dL

• Bilirubin level >2 milligrams/dL

• Platelet count <100,000 cells/μL

• Coagulopathy (INR >1.5)

Treatment:

1_early quantitative resuscitation2_volume resuscitation

3_vasopresser

4_central venous oxygenation

5_lactate clearance

6_treat infection

7_other therapy :ventilation ,glycemic control ,activated protein and steroid

Meningitis :

Meningitis may be bacterial, viral, or occasionally fungal.

Bacterial causes of meningitis include :

meningococci, pneumococci, Haemophilus infl uenzae,

Listeria, and tuberculosis (TB).

Other bacteria may also cause meningitis in

neonates, the elderly, and immunosuppressed patients.

Meningococcal meningitis :

is caused by Neisseria meningitidis. It can resultin septicaemia, coma, and death within a few hours of the first symptoms.

Skin rashes occur in 50 %of patients, often starting as a maculopapular

rash before the characteristic petechial rash develops. There may be DIC

and adrenal haemorrhage

Clinical features:

Some patients with meningitis have the classic features of headache,neck stiffness, photophobia, fever and drowsiness. However, the

clinical diagnosis of meningitis may be very difficult in early cases., or

Meningitis may start as a ‘flu-like’ illness, especially in the

immunosuppressed or elderly. Consider meningitis in any febrile

patient with headache, neurological signs, neck stiffness, or

disturbance conscious level.

Management:

Resuscitate if necessary, give oxygen and obtain venous access. Start antibiotics immediately (without waiting for investigations) if the patient is shocked or deteriorating or there is any suspicion of meningococcal infection (especially a petechial or purpuric rash): give IV ceftriaxone or cefotaxime (adult 2g; child 80mg/kg). Chloramphenicol is an alternative if there is a history of anaphylaxis to cephalosporins .In adults > 55 years add ampicillin 2g qds to cover Listeria. Give vancomycin ±rifampicin if penicillin-resistant pneumococcal infection is suspected. Give IV dexamethasone (0.15mg/kg, max 10mg, qds for 4 days) starting with or just before the first dose of antibiotics, especially if pneumococcal meningitis is suspected.

Toxic shock syndrome :

Toxic shock syndrome (tss) is sever toxin _mediated bacterial disease characterized by shock resulting from an excess inflammatory cytokine .Two important syndrome staphylococcal tss and streptococcal tss are recognized to be cause by S.aureus and streptococcus pyogenes respectively

Clinical criteria :

• Fever: temperature ≥38.9°C or 102.0°F• Rash :diffuse macular erythroderma

• Desquamation:1–2 weeks after onset of rash

• Hypotension: systolic blood pressure ≤90 mm Hg (adult) or <5th percentile by age

(children <16 years of age)

• Multi organ involvement (≥3 organ systems):

° Gastrointestinal: vomiting and/or diarrhea at onset of illness

° Muscular: severe myalgia or CPK ≥2 times the upper limit of normal

° Mucous membrane: vaginal, oropharyngeal, or conjunctival hyperemia

°

Renal: BUN or serum Cr ≥2 times the upper limit of normal for laboratory or urinary

sediment with pyuria (≥5 leukocytes per high-power field) in the absence of urinary

tract infection

° Hepatic: total bilirubin, ALT, or AST ≥2 times the upper limit of normal

° Hematologic: platelet count <100,000/mm3

Diagnosis:

Negative results of:

Blood, throat, and CSF cultures for other bacteria (besides S. aureus)

Negative serology for Rickettsia infection, leptospirosis, and measles

Case classification: • Probable: ≥4 clinical criteria + laboratory criteria met •

Confirmed:5clinical criteria + laboratory criteria met, including desquamation (unless death occurs prior to desquamation)

Treatment:

Management of TSS includes eradication of the focus of infection plus supportive care,which includes fluid resuscitation and vasopressors, as necessary. Large volumes of crystalloids may be required because of the loss of intravascular volume caused by capillary leak.

Circulating bacterial hemolysins may lead to moderate to severe anemia, necessitating blood transfusions. When the focus of infection is identified in staphylococcal TSS, it is important to drain abscesses and treat with appropriate antibiotics.

If a hyper absorbent tampon is in place, it should be removed. Patients who have streptococcal TSS do better with combinations of clindamycin and cell-wall active agents compared to patients who receive cell-wall active agents alone. Because clindamycin is not affected by bacterial inoculum or stage of growth, and because it inhibits synthesis of bacterial toxin, there are theoretical reasons why it would also be effective in these patients. Thus, in both staphylococcal and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome, clindamycin should be included initially.

Staphylococcal TSS should also initially be treated with vancomycin. Antibiotic therapy can be modified once susceptibility data become available. MRSA infections should be treated with vancomycin; MSSA infections with oxacillin; and penicillin-susceptible S. aureus should be treated with penicillin G. Treatment of streptococcal TSS usually includes aggressive surgical debridement, with antibiotic therapy and supportive care. The antibiotic of choice is penicillin G.

NECROTIZING SOFT TISSUE INFECTION

DefinItion :This term include several specific clinical entities characterized by disease processes that produce necrosis of subcutaneous tissue, muscle, or both, and that progress rapidly and require a combined emergent surgical and medical approach for optimal outcomes.

. These entities include necrotizing fasciitis, streptococcal necrotizing myositis, clostridial myonecrosis (gas gangrene), and nonclostridial crepitant myositis.

Necrotizing fasciitis :

Type I necrotizing fasciitis : is a mixed infection caused by an anaerobic bacterium (usually Bacteroides or Clostridium) in association with a facultative anaerobic microorganism, such as a streptococcus or a member of the Enterobacteriaceae.

Type II necrotizing fasciitis, hemolytic streptococcal gangrene, is caused by group A, B, C, or G streptococci. Other microorganisms may be present in the mix. Community-associated methicillin-resistant S. aureus (CA-MRSA) has recently been described as a cause of necrotizing fasciitis.

Diagnosis :

Clinical suspicion is important in order to make an early diagnosis of a necrotizing soft tissue infection. A clue to the presence of a deep necrotizing process is the presence of tenderness clearly beyond the areas of apparent involvement in the skin. Leukocytosis is common. The creatine kinase (CK) level is usually elevated, but may be normal in cases of necrotizing fasciitis with minimal muscle involvement. Ultrasonography, CT scanning, or MRI will usually reveal muscle swelling and fluid in muscle compartments, but may not be apparent early in the disease process. Histopathologic examination will reveal the presence of sheets of neutrophils in fascial planes.Treatment :

• It is not always obvious whether a skin or soft tissue infection is a necrotizing one. When considered a possibility, aggressive management is important. Clinical features cannot accurately predict the causative microorganism. A prudent approach would be to treat with antibiotics that are effective against group A streptococci, S. aureus, enteric gram-negative bacteria, and anaerobic microorganisms until the etiologic diagnosis has been established. The antibiotics of choice for initial empiric therapy are clindamycin plus ampicillin-sulbactam plus ciprofloxacin. If there is reason to suspect MRSA infection, vancomycin should be added. Antibiotic therapy should be modified when culture and susceptibility data become available. A lack of response to a reasonable trial of antibiotics should prompt emergent surgical intervention. Prompt and aggressive fasciotomy and debridement of devitalized tissue are necessary to gain control of the infection. Early surgical intervention reduces mortality. If infection is advanced, amputation may be necessary and lifesaving.Infective endocarditis :

Infection of heart valve native or prosthetic ,endothelial lining ,or congenital anomalyThe most common organisms causing IE are streptococci most common in subacute and staph more common in acute IE

Other less common causative agents are enterococcus spp. Poly microbial fungal and negative blood culture

MR about 20%

Underlying causes are : 1. Rheumatic heart diseases (24%).

2. Congenital heart diseases (19%).3. Other cardiac anomalies (e.g. calcified

aortic valve or mitral valve prolapse (25%).

4. No cardiac anomalies 32%

• Acute endocarditis

Patients present with severe febrile illness with prominent or changing cardiac murmur and petechiae

Subacute endocarditis

develops persistent fever, fatigue, night sweat, weight loss,

new signs of valve dysfunction or heart failure.

Other presentations are embolic stroke, peripheral arterial embolism; and

purpura and petechial haemorrhage (skin & mucus membranes).

Peripheral signs of IE are

Splinter haemorrhage (longitudinal linear haemorrhage under the finger and toe nails),

Osler's nodes (tender nodules at finger tips or thenar eminence),

Jane way lesions (painless macules at the thenar or hypothenar aspects of the palm or sole),

finger clubbing

splenomegaly.

Diagnosis:

Modified Duke criteria: Definite IE: two major, OR one major and three minor, OR five minor Possible IE: one major and one minor OR three minorMajor criteria ;

Positive blood culture

Evidence of echocardiogram

Minor criteria :

Predisposing valvular or cardiac abnormality or Intravenous drug misuse

Pyrexia ≥ 38°C

Vascular phenomena: major arterial emboli, septic pulmonary infarcts, mycotic aneurysm, intracranial hemorrhage, conjunctival hemorrhages,

• and Janeway lesions.

Immunologic phenomena: glomerulonephritis, Osler’s nodes, Roth’s

• spots, and rheumatoid factor

Microbiological evidence: positive blood culture but does not meet

• a major criterion as noted above* or serological evidence of active

• infection with organism consistent with IE

Management :

• Treatment of any possible source of infection (e.g, tooth abscess removal).• Antibiotic therapy:

• can be started empirically until identification of causative organisms; using

Amoxicillin (2 g 6 times daily IV); or

Vancomycin (1 g twice daily IV) and gentamicin (1 mg/kg twice daily IV) in

• patients with acute IE or penicillin allergy; or

Vancomycin (1 g twice daily IV) and gentamicin (1 mg/kg twice daily IV)

• plus rifampicin orally 300–600 mg twice daily in patients with prosthetic valve IE.

Gastroenteritis \food poisoning :

Diarrhoe and vomiting may be caused by many types of bacteria and viruses, and also by some toxins and poisons. Many episodes of gastroenteritis result from contaminated food, usually meat, milk or egg products, which have been cooked inadequately or left in warm conditions. The specifc cause is often not identified. Some infections are spread by faecal contamination of water (e.g cryptosporidiosis from sheep faeces). Rotavirus infection (common in children) may be transmitted by the respiratory route. Severe illness with bloody diarrhoea, haemolysis and renal failure may result from infection with verocytotoxin producing E. coli

History and examination :

Document other symptoms (eg abdominal pain, fever), food and fl uid ingested and drugs taken. Enquire about affected contacts, foreign travel and occupation (especially relevant if a food-handler).Examination:

Look for abdominal tenderness, fever and other signs of infection. Record the patient’s weight and compare this with any previous records. Assess the degree of dehydration—

Clinical evidence of mild dehydration (<5%)

• Thirst.• d urinary output (in a baby <4 wet nappies in 24hr).

• Dry mouth.

Clinical evidence of moderate dehydration (5–10%)

• Sunken fontanelle in infants.

• Sunken eyes.

• Tachypnoea due to metabolic acidosis.

• Tachycardia.

Clinical evidence of severe dehydration (>10%)

• d skin turgor on pinching the skin.

• Drowsiness/irritability.

Treatment:

Hospital treatment is needed if the patient looks seriously ill, dehydration is > 5 % , there is a high fever or the family are unlikely to cope with the patient at home

. Severely dehydrated ( > 10 % ) children need immediate IV fluids, initially 0.9 %saline (10–20mL/kg over 5min, repeated as necessary).

Oral rehydration therapy (ORT)

Recommence normal feeds and diet

Anti-diarrhoeal drugs

Antibiotics

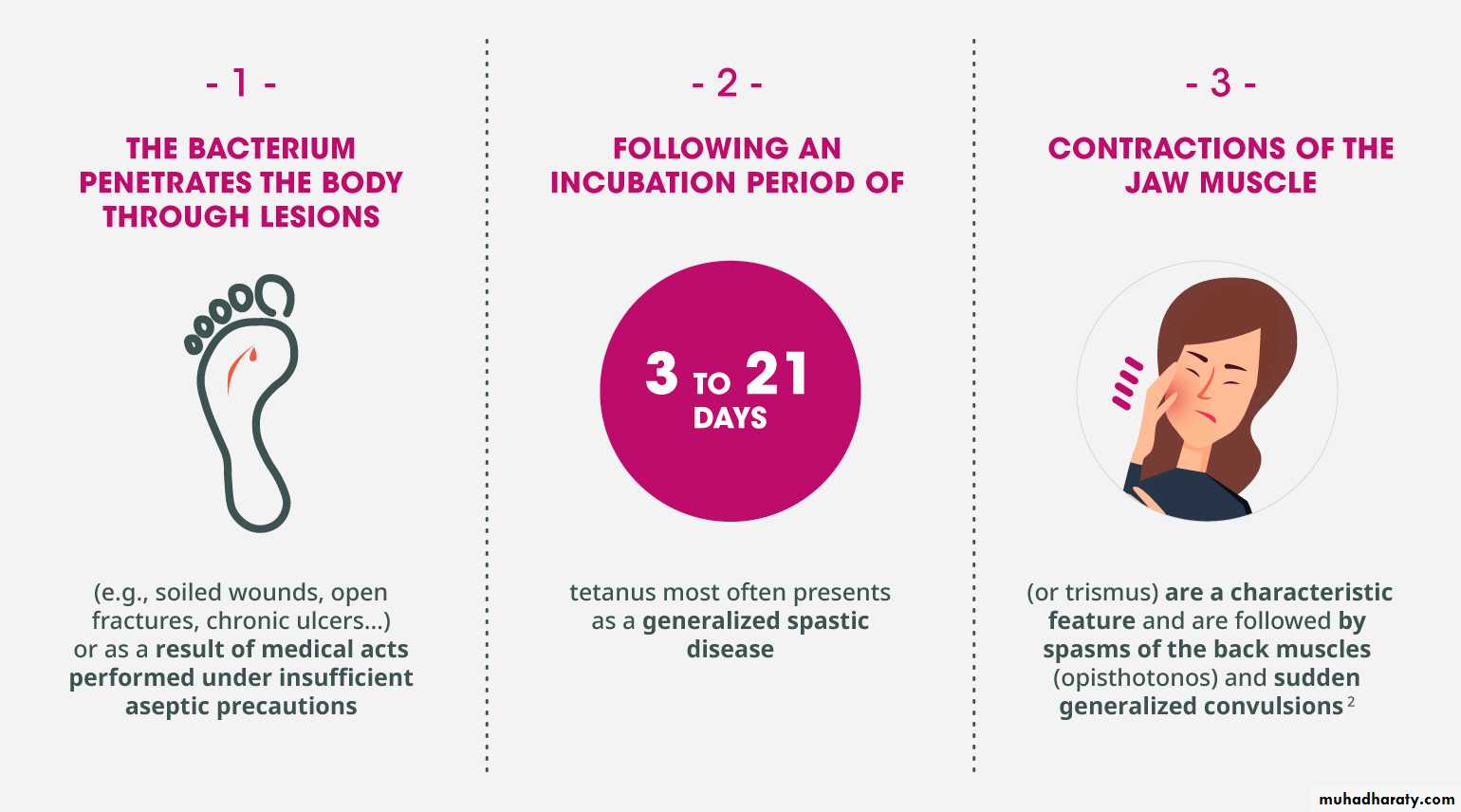

Tetanus :

An acute and often fatal disease Now rare in developed countries:, many involving the elderly. Injecting drug users (eg those ‘skin popping’) are also at particular risk. Spores of the Gram + ve organism Clostridium tetani (common in soil and animal faeces) contaminate a wound, which may be trivial. The spores germinate in anaerobic conditions, producing tetanospasmin, an exotoxin which blocks inhibitory neurones in the CNS and causes muscle spasm and rigidityIncubation period is usually 4–14 days, but may be 1 day to 3 months. In 20 %of cases there is no known wound. Tetanus occasionally occurs after surgery or IM injections

Clinical features:

Stiffness of masseter muscles causes difficulty in opening the mouth (trismus, lockjaw). Muscle stiffness may spread to all facial and skeletal muscles and muscles of swallowing. Characteristically, the eyes are partly closed, the lips pursed and stretched (risus sardonicus). Spasm of chest muscles may restrict breathing. There may be abdominal rigidity, stiffness of limbs and forced extension of the back (opisthotonus). In severe cases, prolonged muscle spasms affect breathing and swallowing. Pyrexia is common. Autonomic disturbances cause profuse sweating, tachycardia and hypertension, alternating with bradycardia and hypotension. Cardiac arrhythmias and arrest may occurManagement:

Obtain senior medical and anaesthetic help. Monitor breathing, ECGand BP. Refer to ICU. Control spasms with diazepam.

Paralyse and ventilate if breathing becomes inadequate.

Clean and debride wounds.

Give penicillin and metronidazole and human tetanus immune globulin.

Anti tetanus prophylaxis :

The need for tetanus immunization after injury depends upon a patient’s

tetanus immunity status and whether the wound is ‘clean’ or ‘tetanus prone.’

The following are regarded as ‘tetanus prone’:

• Heavy contamination (especially with soil or faeces).

• Devitalized tissue.

• Infection or wounds > 6hr old.

• Puncture wounds and animal bites

Patient is already fully immunized If the patient has received a full 5-dose course of tetanus vaccines, do not give further vaccines. Consider human anti-tetanus immunoglobulin (‘HATI’ 250–500units IM) only if the risk is especially high (eg wound contaminated with stable manure).

Not immunized or immunization status unknown or uncertain Give a dose of combined tetanus/diphtheria/polio vaccine and refer to the GP for further doses as required. For tetanus-prone wounds, also give one dose of HATI (250–500units IM) at a different site

Initial course complete, boosters up-to-date, but not yet complete:

Vaccine is not required, but do give it if the next dose is due soon and it is convenient to give it now. Consider human anti-tetanus immunoglobulin (‘HATI’ 250–500units IM) in tetanus prone wounds only if the risk is especially high (e.g wound contaminated with stable manure).Initial course incomplete or boosters not up-to-date:

Give a reinforcing dose of combined tetanus/diphtheria/polio vaccine and refer to the GP for further doses as required to complete the schedule. For tetanus prone wounds, also give one dose of HATI at a different site. The dose of HATI is 250units IM for most tetanus prone wounds, but give 500units if > 24hr have elapsed since injury or if there is heavy contamination or following burn