intestinal obstruction

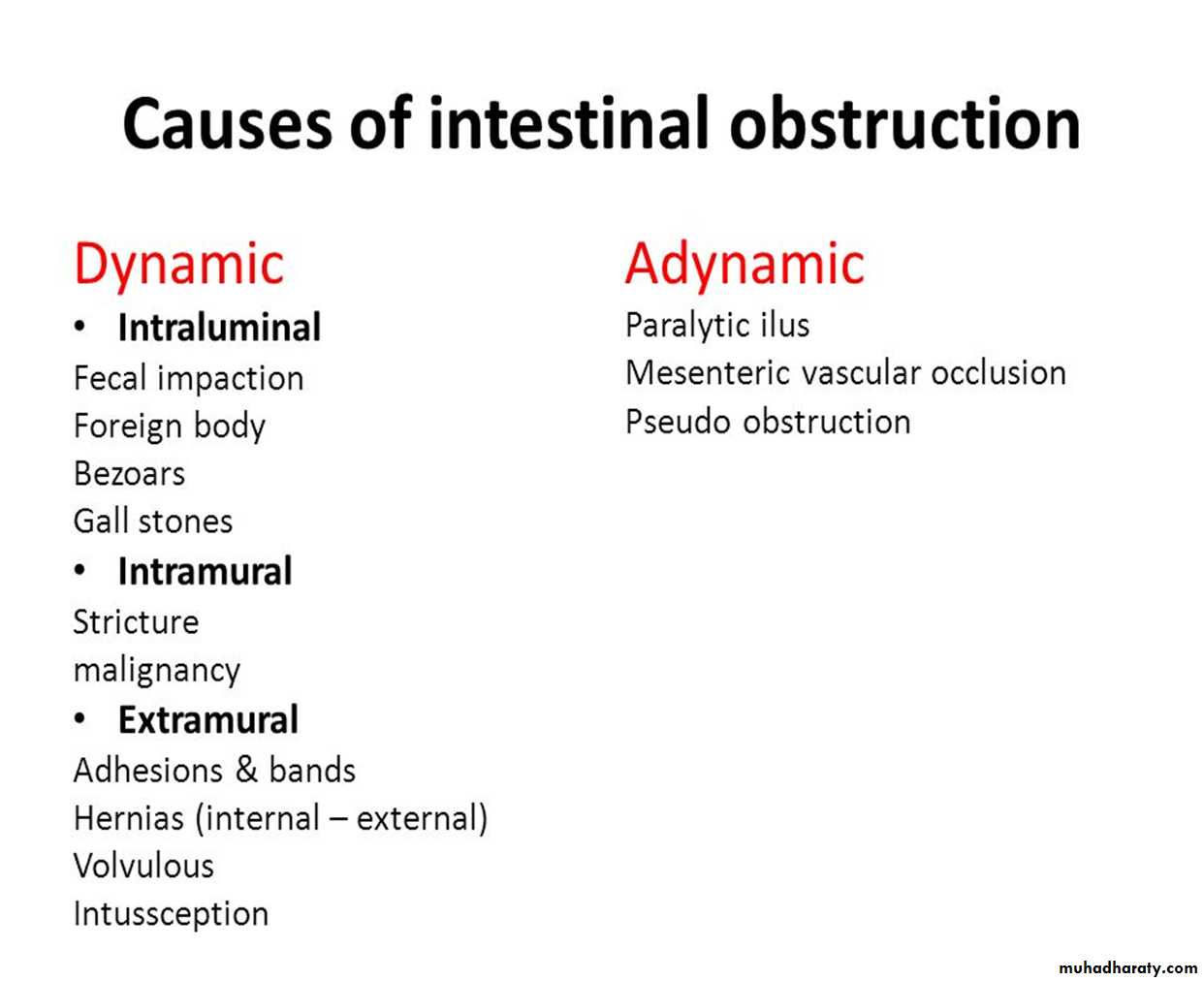

CLASSIFICATIONDynamic:- in which peristalsis is working against a mechanical obstruction. It may occur in an acute or a chronic form.

Adynamic:- in which peristalsis may be absent (e.g. paralyticileus) or it may be present in a non-propulsive form (e.g. mesenteric vascular occlusion or pseudo-obstruction).

In both types a mechanical element is absent.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

In dynamic (mechanical) obstruction the proximal bowel dilates and develops an altered motility.Below the obstruction the bowel exhibits normal peristalsis and absorption until it becomes empty, at which point it contracts and becomes immobile.

Initially, proximal peristalsis is increased to overcome the obstruction, in direct proportion to the distance of the obstruction. If the obstruction is not relieved, the bowel begins to dilate, causing a reduction in peristaltic strength, ultimately resulting in flaccidity and paralysis.

This is a protective phenomenon to prevent vascular damage secondary to increased intraluminal pressure

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The distension proximal to an obstruction is produced by two factors:• Gas: there is a significant overgrowth of both aerobic and anaerobic organisms, the majority is made up of nitrogen (90%) and hydrogen sulphide.

• Fluid: this is made up of the various digestive juices. Dehydration and electrolyte loss are therefore due to:

reduced oral intake;

defective intestinal absorption;

losses as a result of vomiting;

sequestration in the bowel lumen

STRANGULATION

The venous return is compromised before the arterial supply. The resultant increase in capillary pressure leads to local mural distension with loss of intravascular fluid and red blood cells intra murally and extraluminally.

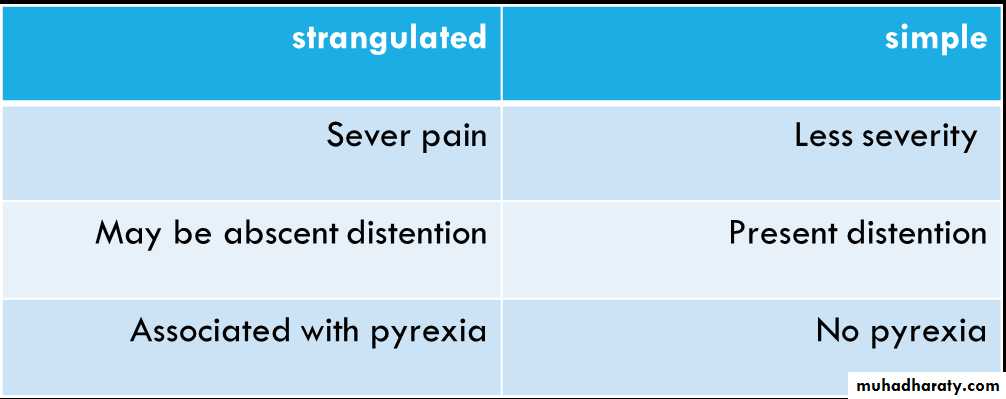

How differentiate strangulated from simple obstruction :

ADHESION

Any source of peritoneal irritation results in local fibrin production, which produces adhesions between apposed surfaces. Postoperative adhesions giving rise to intestinal obstruction usually involve the lower small bowel. usually early post operative(few weeks)Operations for appendicitis and gynecological procedures are the most common precursors and are an indication for early intervention.

The most common causes:-

Ischemic area.Foreign material.

Inflammatory condition (CROHNS disease).

Adhesion preventive strategies

Peritoneal washing with N/S.Limit contact with gauze.

Good surgical technique.

Any area of anastomosis or raw peritoneal surface should be covered.

Bands

This may be:

• congenital, e.g. obliterated vitellointestinal duct;

• a string band following previous bacterial peritonitis;

• a portion of greater omentum, usually adherent to the parities.

Acute intussusception

This occurs when one portion of the gut becomes invaginated within an immediately adjacent segment; almost invariably, it is the proximal into the distal.Associated with respiratory infection.

Factors: idiopathic or have HX of diverticulum ,appendicitis.

Volvulus

A volvulus is a twisting or axial rotation of a portion of bowel about its mesentery. When complete it forms a closed loop of obstruction with resultant ischemia secondary to vascular occlusion.Most common in sigmoid and also in cecum.

Internal hernia

Internal herniation occurs when a portion of the small intestine becomes entrapped in one of the retroperitoneal fossae or in a congenital mesenteric defect.Obstruction from enteric strictures

Small bowel strictures usually occur secondary to tuberculosis or Crohn’s disease.Malignant strictures associated with lymphoma are common, whereas carcinoma and sarcoma are rare.

Gallstones

This type of obstruction tends to occur in the elderly secondary to erosion of a large gallstone through the gall bladder into the duodenum. Classically, there is impaction about 60 cm proximal to the ileocaecal valve. The patient may have recurrent attacks as the obstruction is frequently incomplete . At laparotomy it may be possible to crush the stone within the bowel lumen, after milking it proximally. If not, the intestine is opened and the gallstone removed.

Food

Bolus obstruction may occur after partial or total gastrectomy when unchewed articlescan pass directly into the small bowel.

Fruit and vegetables are particularly liable to cause obstruction.

Worms

Ascaris lumbricoides may cause low small bowel obstruction, particularly in children and also occur in those near the tropics.CLINICAL FEATURES OF INTESTINAL OBSTRUCTION

Dynamic obstructionThe diagnosis of dynamic intestinal obstruction is based on the classic quartet of pain, distension, vomiting and absolute constipation. Obstruction may be classified clinically into two types:

• small bowel obstruction – high or low;

• large bowel obstruction.The nature of the presentation will also be influenced by whether the obstruction is:

Acute, chronic ,acute on chronic and subacute.Acute obstruction usually occurs in small bowel obstruction, with sudden onset of severe colicky central abdominal pain, distension and early vomiting and constipation

Chronic obstruction is usually seen in large bowel obstruction, with lower abdominal colic and absolute constipation followed by distension.

The clinical features vary according to:

• the location of the obstruction;• the age of the obstruction;

• the underlying pathology;

• the presence or absence of intestinal ischemia.

PAIN

Pain is the first symptom encountered; it occurs suddenly and is usually severe.It is colicky in nature and is usually centered on the umbilicus (small bowel) or lower abdomen (large bowel).

The development of severe pain is indicative of the presence of strangulation.

Pain may not be a significant feature in postoperative simple mechanical obstruction and does not usually occur in paralytic ileus.

VOMITING

The more distal the obstruction, the longer the interval between the onset of symptoms and the appearance of nausea and vomiting.As obstruction progresses the character of the vomitus alters from digested food to feculent material, as a result of the presence of enteric bacterial overgrowth.

Constipation

This may be classified as absolute (i.e. neither faeces nor flatus is passed) or relative(where only flatus is passed).Absolute constipation is a cardinal feature of complete intestinal obstruction.

Other manifestations

Dehydration

Hypokalaemia

Pyrexia

Pyrexia in the presence of obstruction may indicate:• the onset of ischaemia;

• intestinal perforation;

• inflammation associated with the obstructing disease.

Hypothermia indicates septicemic shock.

Abdominal tenderness

Localized tenderness indicates pending or established ischemia.The development of peritonism or peritonitis indicates overt infarction and/or

perforation.IMAGING

Erect abdominal films are no longer routinely obtained and the radiological diagnosis isbased on a supine abdominal film.

In intestinal obstruction, fluid levels appear later than gas shadows as it takes time for

gas and fluid to separate .

A barium follow-through is contraindicated in the presence of acute obstruction and may be life-threatening.

Impacted foreign bodies may be seen on abdominal radiographs.

In gallstone ileus, gas may be seen in the biliary tree, with the stone visible

TREATMENT OF ACUTE INTESTINAL OBSTRUCTION

There are three main measures used to treat acute intestinal obstruction

■ Gastrointestinal drainage

■ Fluid and electrolyte replacement

■ Relief of obstruction , Surgical treatment is necessary for most

obstruction but should be delayed until resuscitation is complete,

provided there is no sign of strangulation or evidence of closed-

loop obstruction.

Supportive management

Nasogastric decompression is achieved by the passage of a nasogastric tube. The tubesare normally placed on free drainage with 4-hourly aspiration but may be placed on

continuous or intermittent suction. As well as facilitating decompression proximal to the

obstruction, they also reduce the risk of subsequent aspiration during induction of

anesthesia and post-extubation.

The basic biochemical abnormality in intestinal obstruction is sodium and water loss, and

therefore the appropriate replacement is Hartmann’s solution or normal saline.Antibiotics are not mandatory but many clinicians initiate broad-spectrum antibiotics

early in therapy because of bacterial overgrowth. Antibiotic therapy is mandatory for allpatients undergoing small or large bowel resection.

Surgical treatment

The timing of surgical intervention is dependent on the clinical picture.

There are several indications for early surgical intervention

The classic clinical advice that ‘the sun should not both rise and set’ on a

case of unrelieved acute intestinal obstruction is sound and should befollowed unless there are positive reasons for delay. Such cases may

include obstruction secondary to adhesions when there is no pain or

tenderness, despite continued radiological evidence of obstruction.

In these circumstances, conservative management may be continued for up to 72 hours in the hope of spontaneous resolution.

If the site of obstruction is unknown, adequate exposure is best achieved

by a midline incision. Assessment is directed to:• the site of obstruction;

• the nature of the obstruction;

• the viability of the gut.

Treatment of adhesions

Initial management is based on intravenous rehydration and nasogastric decompression.occasionally, this treatment is curative.

Although an initial conservative regimen is considered appropriate, regular

assessment is mandatory to ensure that strangulation does not occur.

Conservative treatment should not be prolonged beyond 72 hours.

Treatment of intussusception

In the infant with ileocolic intussusception, after resuscitation with intravenous

fluids, broad-spectrum antibiotics and nasogastric drainage, non-operative

reduction can be attempted using an air or barium enema .

Successful reduction can only be accepted if there is free reflux of air or barium into the small bowel, together with resolution of symptoms and signs in the patient.

Non-operative reduction is contraindicated if there are signs of peritonitis or

perforation, there is a known pathological lead point or in

the presence of profound shock.

Surgery is required when radiological reduction has failed or is contraindicated.

ADYNAMIC OBSTRUCTION

Paralytic ileusThis may be defined as a state in which there is failure of transmission of

peristaltic waves secondary to neuromuscular failure [i.e. in the myenteric

(Auerbach’s) and submucous (Meissner’s) plexuses]. The resultant stasis

leads to accumulation of fluid and gas within the bowel, with associated

distension, vomiting, absence of bowel sounds and absolute constipation.

The following varieties are recognized.

Postoperative: a degree of ileus usually occurs after any abdominal procedure and is self-limiting, with a variable duration of 24–72 hours.Infection: intra-abdominal sepsis may give rise to localized or generalized ileus.

Reflex ileus: this may occur following fractures of the spine or ribs, retroperitoneal hemorrhage.

Metabolic: uremia and hypokalemia are the most common contributory factors.

Clinical features

Paralytic ileus takes on a clinical significance if, 72 hours after laparotomy:

• there has been no return of bowel sounds on auscultation;

• there has been no passage of flatus

Abdominal distension becomes more marked and tympanitic.

Pain is not a feature. In the absence of gastric aspiration, effortless vomiting may occur.

Radiologically, the abdomen shows gas filled loops of intestine with multiple fluid levels.

Management

The treatment is prevention, with the use of nasogastric suction and restriction of oralintake until bowel sounds and the passage of flatus return and Electrolyte balance must

be maintained.

The use of an enhanced recovery program with early introduction of fluids and solids

is becoming increasingly popular

Specific treatment is directed towards the cause, but the following general principles

apply:

• The primary cause must be removed.

• Gastrointestinal distension must be relieved by decompression.

• Close attention to fluid and electrolyte balance is essential.

• There is no place for the routine use of peristaltic stimulants.

Rarely, in resistant cases, medical therapy with an adrenergic blocking

agent in association with cholinergic stimulation, e.g. neostigmine , may be

used, provided that an intraperitoneal cause has been excluded.

If paralytic ileus is prolonged and threatens life, a laparotomy should be

considered to exclude a hidden cause and facilitate bowel

decompression.