Upper GI Bleeding&Portal Hypertension

Dr. Ali Jaffer

Background

Bleeding derived from a source proximal to the ligament of Treitz.

Bleeding from the upper

GI tract is approximately 4 times more common than bleeding from the lower GI tract.

Mortality rates from UGIB are 6-10% overall.

Comorbid diseases increase the death rate.

Rebleeding and continued bleeding is a significant factor of mortality.

Aetiology

Causes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

Ulcers 60%

Oesophageal 6%

Gastric 21%

Duodenal 33%

Erosions 26%

Oesophageal 13 %

Gastric 9%

Duodenal 4 %

Mallory–Weiss tear 4 %

Oesophageal varices 4 %

Tumour 0.5 %

Vascular lesions, e.g. Dieulafoy’s disease 0.5 %

Others 5%

Prognosis

The following risk factors are associated with an increased mortality, recurrent bleeding, the

need for endoscopic hemostasis, or surgery

:

1. Age older than 60 years

2. Severe comorbidity

3. Active bleeding (eg, witnessed hematemesis, red blood per nasogastric tube, fresh blood per

rectum)

4. Hypotension

5. Red blood cell transfusion greater than or equal to 6 units

6. Inpatient at time of bleed

7. Severe coagulopathy

Patients who present in hemorrhagic shock have a mortality rate of up to 30%

History

Important information

potential comorbid conditions,

medication history, and potential toxic exposures

severity, timing, duration, and volume of the bleeding

Hematemesis, Melena, Hematochezia

Syncope

Dyspepsia, Epigastric pain, Heartburn, Diffuse abdominal pain

Dysphagia, Weight loss

Jaundice

Physical Examination

The goal; to evaluate for shock and blood loss.

Assessing the patient for hemodynamic

instability and clinical signs of poor perfusion is important early in the initial evaluation to

properly triage patients with massive hemorrhage.

Worrisome clinical signs and symptoms of hemodynamic compromise include: Tachycardia

of more than 100 beats per minute (bpm), Systolic blood pressure of less than 90 mm Hg,

Cool extremities, syncope, and other obvious signs of shock, Ongoing brisk hematemesis, The

occurrence of maroon or bright-red stools, which requires rapid blood transfusion.

Pulse and blood pressure should be checked with the patient in supine and upright positions to

note the effect of blood loss. Significant changes in vital signs with postural changes indicate

an acute blood loss of approximately 20% or more of the blood volume.

Signs of chronic liver disease should be noted, including spider angiomata, gynecomastia,

splenomegaly, ascites, ....etc. nodular liver, an abdominal mass, and enlarged and firm lymph

nodes.

Work up

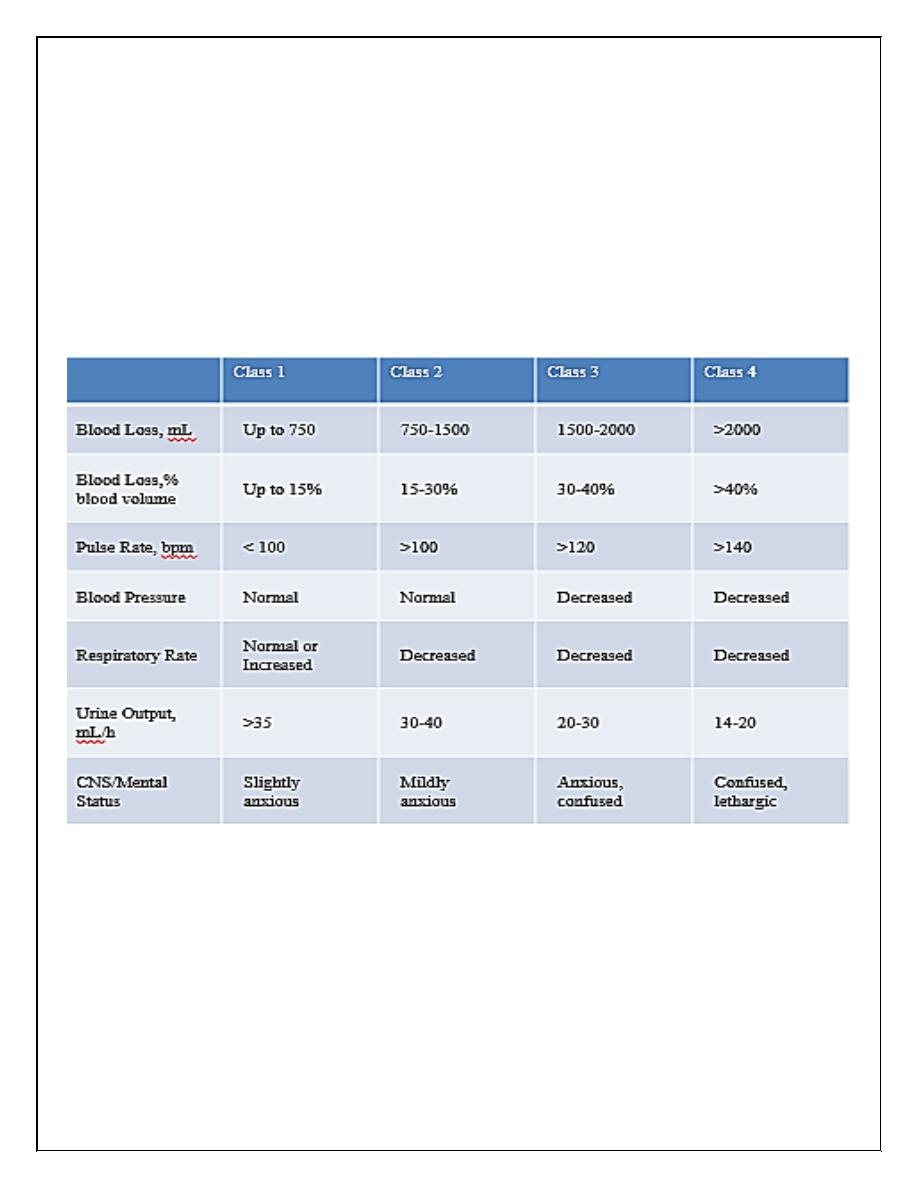

Assessment of hemorrhagic shock

patients who present in hemorrhagic shock have a mortality rate of up to 30%

Estimated Fluid and Blood Losses in Shock:

Hemoglobin Value and Type and Crossmatch Blood

CBC should be checked frequently (4-6h) during the first day. The patient should be

crossmatched for 2-6 units, based on the rate of active bleeding. Patients with significant

comorbid conditions (eg, advanced cardiovascular disease) should receive blood transfusions

to maintain myocardial oxygen delivery to avoid myocardial ischemia.

The more units required, the higher the mortality rate. Operative intervention is indicated once

the blood transfusion number reaches more than 5 units.

Coagulation Profile

The patient's prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (PTT), and

international normalized ratio (INR) should be checked to document the presence of

coagulopathy. The coagulopathy may be consumptive and associated with a

thrombocytopenia

Endoscopy

Diagnostic&therapeutic. Endoscopy should be performed immediately after endotracheal

intubation (if indicated), hemodynamic stabilization, and adequate monitoring in an intensive

care unit (ICU) setting have been achieved.

Chest Radiography

Computed Tomography Scanning

Liver disease for cirrhosis, pancreatitis with pseudocyst and hemorrhage, aortoenteric fistula,

and other unusual causes of upper GI hemorrhage.

Nuclear Medicine Scanning

Nuclear medicine scans may be useful in determining the area of active hemorrhage.

Angiography

Angiography may be useful if bleeding persists and endoscopy fails to identify a bleeding

site.

Transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) should be considered for all patients with a

known source of arterial UGIB that does not respond to endoscopic management, with

active bleeding and a negative endoscopy.

Nasogastric Lavage, PPIs, Treatment of underlying cause

Portal Hypertension

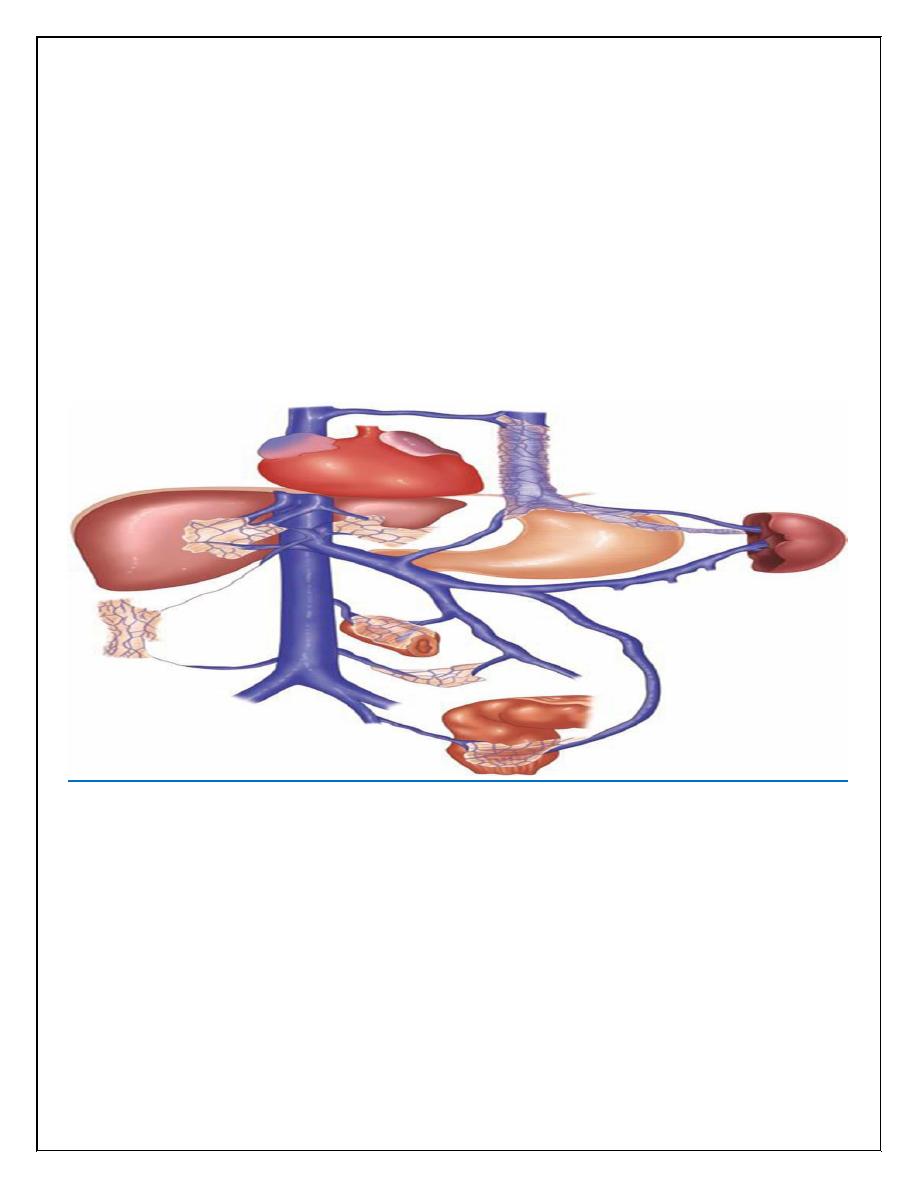

The portal venous system contributes approximately 75% of the blood and 72% of the oxygen

supplied to the liver. In the average adult, 1000 to 1500 mL/min of portal venous blood is

supplied to the liver. The normal portal venous pressure is 5 to 10 mmHg, and at this pressure,

very little blood is shunted from the portal venous system into the systemic circulation. As

portal venous pressure increases, the collateral communications with the systemic circulation

dilate, and a large amount of blood may be shunted around the liver and into the systemic

circulation.

Lower oesophagus; Left gastric veins (portal system) -> lower branches of oesophageal veins

(systemic veins)

Upper part of anal canal; Superior rectal veins (portal) -> inferior and middle rectal veins

(systemic)

Umbilicus; Paraumbilical veins (portal) -> epigastric veins (systemic)

Area of the liver; Intraparenchymal branches of right division of portal vein (portal) ->

retroperitoneal veins (systemic)

Hepatic and splenic flexures; Omental and colonic veins (portal) -> retroperitoneal veins

(systemic)

Aetiology of portal hypertension

1- Presinusoidal

Sinistral/extrahepatic

Splenic vein thrombosis, Splenomegaly, Splenic arteriovenous fistula

Intrahepatic

Schistosomiasis, Congenital hepatic fibrosis, Nodular regenerative hyperplasia, Idiopathic

portal fibrosis, Myeloproliferative disorder, Sarcoid, Graft-versus-host disease

2- Sinusoidal

Intrahepatic: Cirrhosis, Viral infection, Alcohol abuse, Primary biliary cirrhosis, Autoimmune

hepatitis, Primary sclerosing cholangitis, Metabolic abnormality

3- Postsinusoidal

Intrahepatic: Vascular occlusive disease

Posthepatic

Budd-Chiari syndrome, Congestive heart failure, Inferior vena caval web, Constrictive

pericarditis

Portal hypertension per se produces no symptoms, it is usually diagnosed following

presentation with decompensated chronic liver disease and encephalopathy, ascites or variceal

bleeding.

Management of bleeding varices

General resuscitation

Medical emergency, ICU

Two large pore peripheral canulae, Resuscitation, avoid fluid overload (why?)

Correction of coagulopathy; Vit K(10mg) i.v., tranexamic acid (1g i.v), FFP, platelet

transfusion

Activation of major blood transfusion protocol

Drug therapy (terlipressin) splanchnic vasoconstriction

Prophylactic antibiotics

Endoscopy ; 50% PHT non variceal bleeding

Sengstaken-Blakemore, temporary control; Once inserted, the gastric balloon is inflated with

300 mL of air and retracted to the gastric fundus, where the varices at the oesophagogastric

junction are tamponaded by the subsequent inflation of the oesophageal balloon to a pressure

of 40 mmHg. The balloons should be temporarily deflated after 12 hours to prevent pressure

necrosis of the oesophagus.

Endoscopic treatment of varices

Endoscopic band ligation, endoscopic sclerotherapy

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent shunts

the main treatment of variceal haemorrhage that has not responded to drug treatment and

endoscopic therapy.

Complications:

Liver capsule perfuration…. Intraperitoneal hemorrhage, Occlusion resulting

in further variceal bleeding, Post shunt encephalopathy 40% of cases, TIPS stenosis (50%

after one year)

Surgical shunts for variceal haemorrhage

Surgical shunts are an effective method of preventing rebleeding from oesophageal or gastric

varices, as they reduce the pressure in the portal circulation by diverting the blood into the

low-pressure systemic circulation.

Long-term β-blocker therapy and chronic sclerotherapy or

banding are the main alternatives.

Liver transplantation

is the only therapy that will treat both portal hypertension and the

underlying liver disease.

Ascites

Portal vein thrombosis is a common predisposing factor to the development of ascites in

chronic liver disease. In patients without evidence of liver disease, malignancy is a common

cause

Aspiration of the peritoneal fluid allows the measurement of protein content to determine

whether the fluid is an exudate or transudate, an amylase estimation to exclude pancreatic

ascites.

Cytology will determine the presence of malignant cells. Microscopy and culture will

exclude primary bacterial and tuberculous peritonitis.

Treatment of ascites in chronic liver disease

Salt restriction, Diuretics

Abdominal paracentesis

TIPSS

Liver transplantation