1

LYMPHOMA:

Objective :To understand types , epidemiology, clinical presentations , diagnosis

and lines of treatment of lymphoma.

Lymphoma is the third most common cancer in children (age 14 yr or younger). It

is the most common cancer in adolescents, accounting for >25% of newly

diagnosed cancers in persons 15-19 yr old.

The 2 categories of lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) and non- Hodgkin

lymphoma (NHL), have different clinical manifestations and treatments.

Hodgkin Lymphoma:

Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) is a malignant process involving the lymphoreticular

system that accounts for 6% of childhood cancers. HL accounts for approximately

5% of cancers in persons 14 yr of age or younger; it accounts for approximately

15% of cancers in adolescents (15-19 yr of age), making HL the most common

malignancy in this age group.

2

EPIDEMIOLOGY:

The worldwide incidence of HL is approximately 2-4 new cases/100,000

population/yr; there is a age distribution, with peaks at 15-35 yr of age and again

after 50 yr.

It is the most common cancer seen in adolescents and young adults, and the third

most common in children younger than the age of 15 yr.

A male : female predominance is found among young children .

Infectious agents may be involved, such as human herpesvirus 6, cytomegalovirus,

and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV).

Infection with EBV leads to a 4-fold higher risk of developing HL and may

precede the diagnosis by years. EBV antigens have been demonstrated in HL

tissues, particularly type II latent membrane proteins 1 and 2, although EBV status

is not thought to be prognostic of outcome.

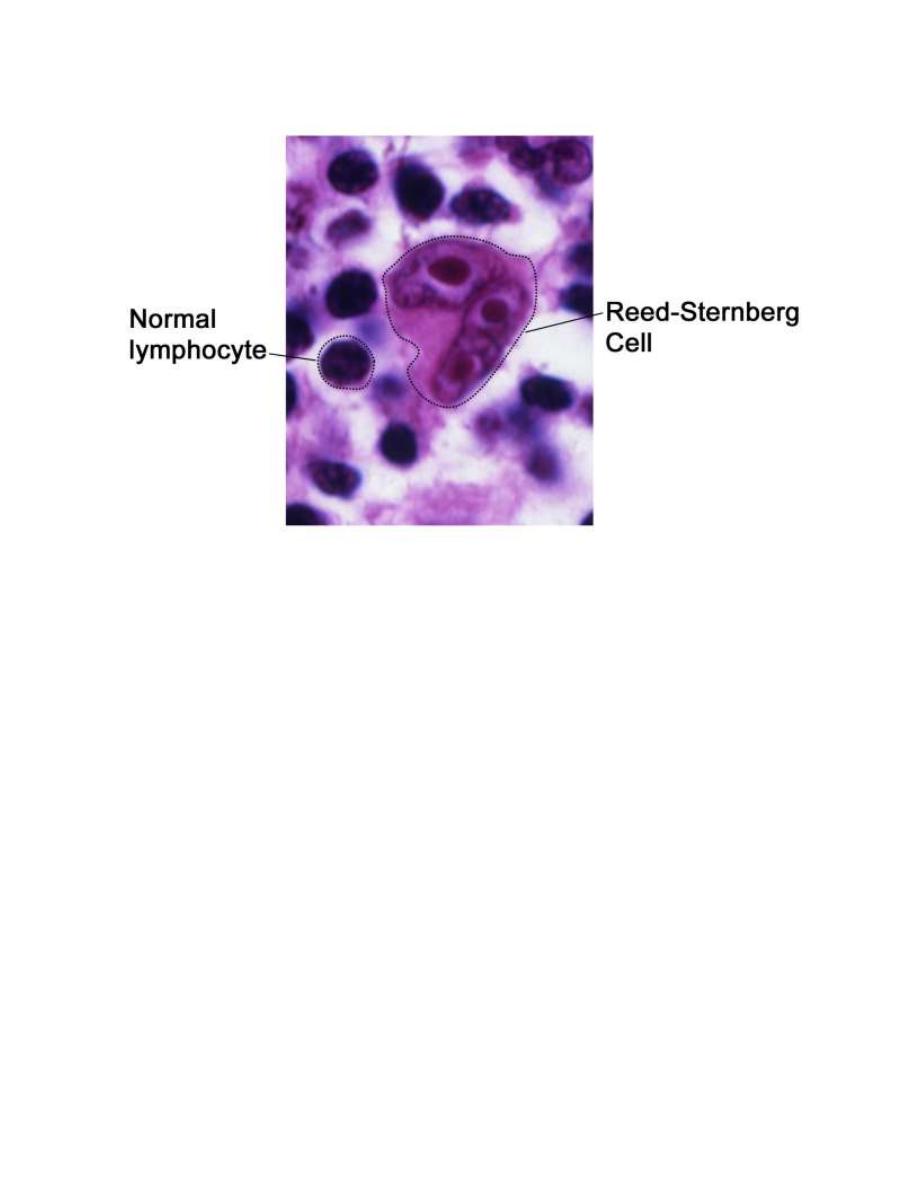

PATHOGENESIS:

The Reed-Sternberg (RS) cell, a pathognomonic feature of HL, is alarge cell (15-

45 μm in diameter) with multiple or multilobulated nuclei. This cell type is

considered the hallmark of HL, although similar cells are seen in infectious

mononucleosis, NHL, and other conditions.

The RS cell is clonal in origin and arises from the germinal center B cells but

typically has lost most B-cell gene expression and function.

HL is characterized by a variable number of RS cells surrounded by an

inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes ,plasma cells, and eosinophils in different

proportions, depending on the HL histologic subtype.

Reactive infiltration of eosinophils and CD68+ macrophages, and increased

concentrations of cytokines, such as interleukins 1 and 6 and tumor necrosis factor,

are all associated with an unfavorable prognosis ,including advanced stage, the

presence of “B” symptoms, decreased response to therapy, and reduced survival.

Other features that distinguish the histologic subtypes include various degrees of

fibrosis and the presence of collagen bands, necrosis, or malignant reticular cells.

The distribution of subtypes varies with age.

Hematogenous spread also occurs, leading to involvement of the liver, spleen,

bone, bone marrow, or brain, and is usually associated with systemic symptoms.

3

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS:

Patients commonly present with painless, nontender, firm, rubbery, cervical or

supraclavicular lymphadenopathy and usually some degree of mediastinal

involvement.

Clinically detectable hepatosplenomegaly is rarely encountered.

Depending on the extent and location of nodal and extranodal disease, patients

may present with symptoms and signs of airway obstruction (dyspnea, hypoxia,

cough), pleural or pericardial effusion, hepatocellular dysfunction, or bone

marrow infiltration (anemia, neutropenia, or thrombocytopenia).

Disease manifesting below the diaphragm is rare and occurs in approximately 3%

of all cases.

Systemic symptoms, classified as B symptoms that are considered important in

staging, are unexplained fever >38°C (100.4°F), weight loss >10% total body

weight over 6 mo, and drenching night sweats.

Less common and not considered of prognostic significance are symptoms of

pruritus, lethargy, anorexia, or pain that worsens after ingestion of alcohol.

Patients also exhibit immune system abnormalities that often persist during and

after therapy.

4

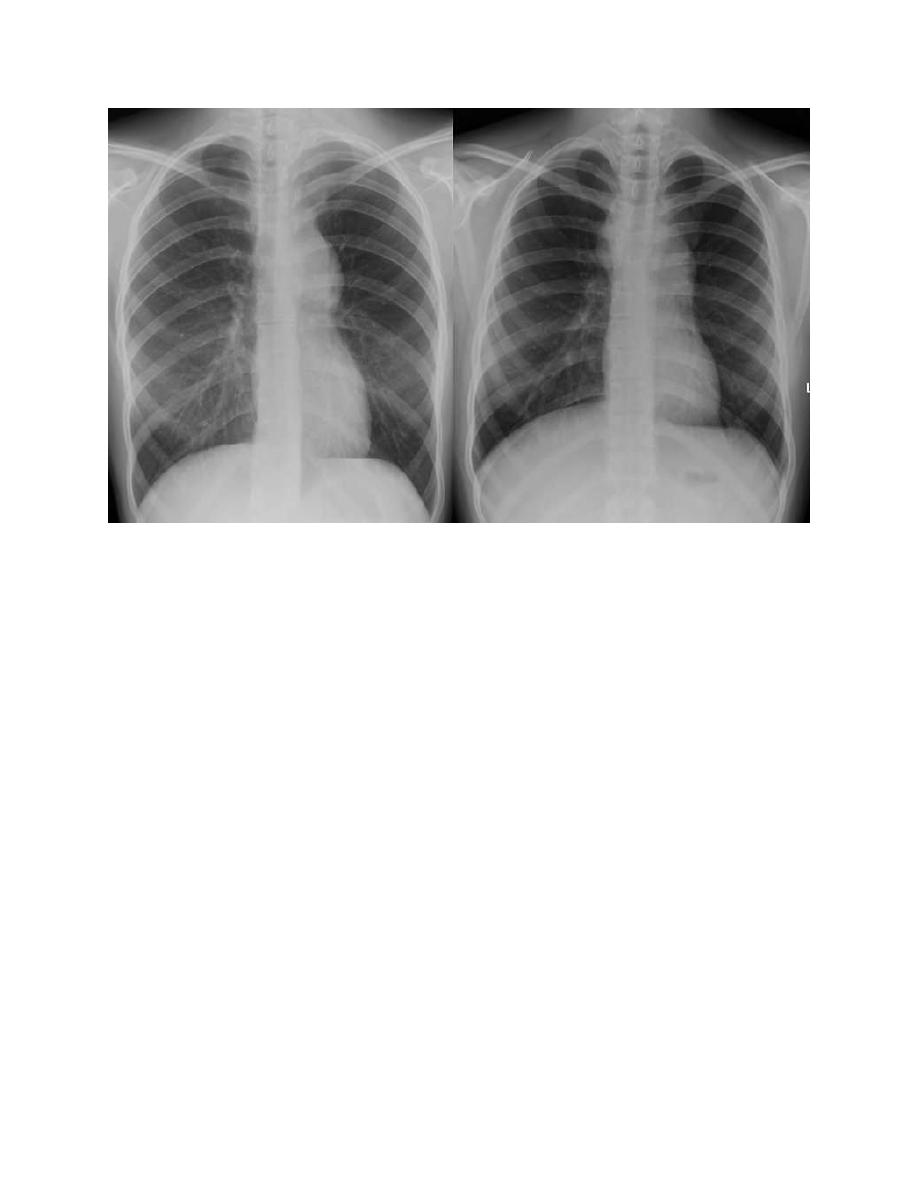

DIAGNOSIS:

Any patient with persistent, unexplained lymphadenopathy unassociated with an

obvious underlying inflammatory or infectious process should undergo chest

radiography to identify the presence of a large mediastinal mass before undergoing

lymph node biopsy.

Excisional biopsy is preferred over needle biopsy to ensure that adequate tissue is

obtained, both for light microscopy and for appropriate immunohistochemical and

molecular studies.

Once the diagnosis of HL is established, extent of disease (stage) should be

determined to allow selection of appropriate therapy .

Evaluation includes history, physical examination, and imaging studies, including

chest radiograph; CT scans of the neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis; and positron

emission tomography (PET) scan.

Laboratory studies should include a complete blood cell count to identify

abnormalities that might suggest marrow involvement; erythrocyte sedimentation

rate; and measurement of serum ferritin, which is of some prognostic significance

and, if abnormal at diagnosis, serves as a baseline to evaluate the effects of

treatment .

e 496-2 Ann Arbor Staging Classification for

STAGE DEFINITION

Stage I Involvement of a single lymph node (I) or of a single extralymphatic organ

or site (IE)

Stage II Involvement of 2 or more lymph node regions on the same side of the

diaphragm (II) or localized involvement of an extralymphatic organ or site and 1 or

more lymph node regions on the same side of the diaphragm (IIE)

Stage III Involvement of lymph node regions on both sides of the diaphragm (III),

which may be accompanied by involvement of the spleen (IIIS) or by localized

involvement of an extralymphatic organ or site (IIIE) or both (IIISE)

Stage IV Diffuse or disseminated involvement of 1 or more extralymphatic organs

or tissues with or without associated lymph node involvement

*The absence or presence of fever >38°C (100.4°F) for 3 consecutive days,

drenching night sweats, or unexplained loss of >10% of body weight in the 6 mo

preceding admission are to be denoted in all cases by the suffix letter A or B,

respectively.

A chest radiograph is particularly important for measuring the size of the

mediastinal mass in relation to the maximal diameter of the thorax . This

determines “bulk” disease and becomes prognostically significant.

Chest CT more clearly defines the extent of a mediastinal mass if present and

identifies hilar nodes and pulmonary parenchymal involvement, which may not be

evident on chest radiographs.

5

Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy should be performed to rule out advanced

disease.

Bone scans are performed in patients with bone pain and/or elevation of alkaline

phosphatase

Fluorodeoxyglucose PET imaging has advantages over gallium scanning, as it is a

1-day procedure with higher resolution, better dosimetry, less intestinal activity,

and the potential to quantify disease. PET scans are being evaluated as a prognostic

tool in HL, enabling therapy to be reduced in those predicted to have a good

outcome.

HL can be subclassified into A or B categories: A is used to identify asymptomatic

patients and B is for patients who exhibit any B symptoms.

Extralymphatic disease resulting from direct extension of an involved lymph node

region is designated by category E.

A complete response in HL is defined as the complete resolution of disease on

clinical examination and imaging studies or at least 70-80% reduction of disease

and a change from initial positivity to negativity on either gallium or PET

scanning because residual fibrosis is common.

6

TREATMENT:

Chemotherapy and radiation therapy are both effective in the treatment of HL.

Treatment is determined largely by disease stage, presence or absence of B

symptoms ,and the presence of bulky nodal disease.

Radiation therapy caused significant long-term morbidity in pediatric patients,

including growth retardation, thyroid dysfunction, and cardiac and pulmonary

toxicity.

Chemotherapy agents commonly used to treat children and adolescents with HL

include cyclophosphamide, procarbazine, vincristine or vinblastine, prednisone or

dexamethasone, doxorubicin, bleomycin, dacarbazine, etoposide, methotrexate,

and cytosine arabinoside.

The combination chemotherapy regimens in current use are based on COPP

(cyclophosphamide, vincristine [Oncovin], procarbazine, and prednisone) or

ABVD (doxorubicin [Adriamycin], bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine).

The aim is to reduce total drug doses and treatment duration and to eliminate

radiation therapy if possible.

Patients who achieve an initial chemosensitive response but relapse or progress

less than 12 mo from diagnosis are candidates for chemotherapy and autologous

stem cell transplantation with or without the addition of radiation therapy.

PROGNOSIS:

With the use of current therapeutic regimens, patients with favorable prognostic

factors and early-stage disease have an overall survival (OS) at 5 yr of >95%.

Patients with advanced-stage disease have slightly lower OS (90%),, although OS

has approached 100% with doseintense chemotherapy .

RELAPSE:

Most relapses occur within the 1st 3 yr after diagnosis, but relapses as late as 10 yr

have been reported. Relapse cannot be predicted accurately with this disease.

Poor prognostic features include tumor bulk, stage at diagnosis, extralymphatic

disease, and presence of B symp- on the time from completion of treatment to

recurrence, site of relapse (nodal vs extranodal), and presence of B symptoms at

relapse.

A myeloablative autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with refractory

disease or /’relapse within 12 mo of therapy results in a long-term survival rate of

only 40-50%.

.

7

Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma:

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) accounts for approximately 60% of lymphomas in

children and is the second most common malignancy in patients age 15-35 yr.

Pediatric NHL is usually high grade and aggressive. Although more than 70% of

patients present with advanced disease, the prognosis has improved dramatically,

with survival rates of 90-95% for localized disease and 70-95% with advanced

disease.

EPIDEMIOLOGY:

Although most children and adolescents with NHL present as primary disease, a

small number of patients have NHL secondary to specific etiologies, including

inherited or acquired immune deficiencies (e.g., severe combined

immunodeficiency syndrome, Wiskott-Aldrichsyndrome), viruses (e.g., HIV,

EBV), and as part of genetic syndromes (e.g., ataxia-telangiectasia, Bloom

syndrome).

PATHOGENESIS:

The 4 major pathologic subtypes of childhood and adolescent NHL are

lymphoblastic lymphoma (LBL), Burkitt lymphoma (BL), diffuse large B-cell

lymphoma (DLBCL), and anaplastic large cell aberrations.

Children with BL commonly have a t(8;14) translocation (90%) .

Children with BL who have a 13q deletion or complex karyotype have a poor

prognosis.

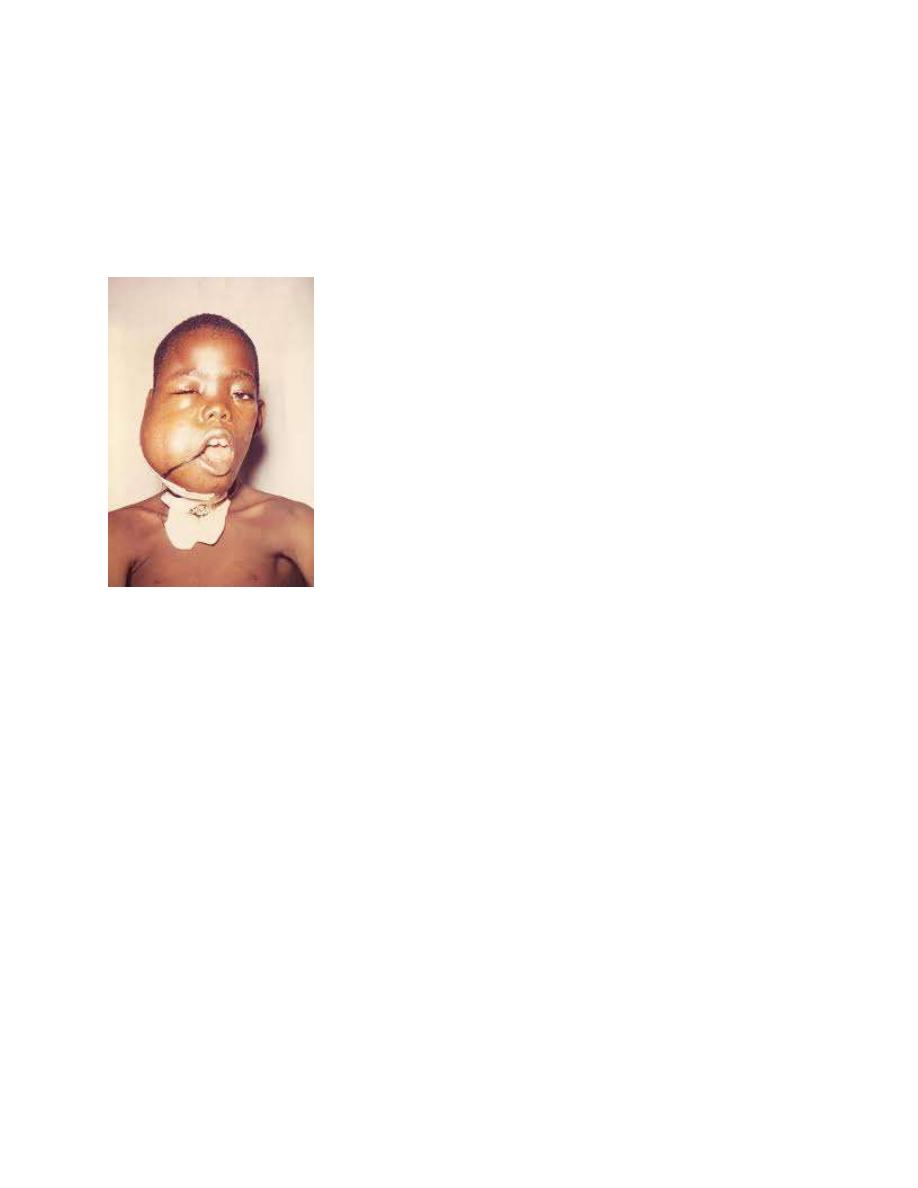

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS:

The clinical manifestations of childhood and adolescent NHL depend primarily on

pathologic subtype and sites of involvement.

BL commonly manifests as abdominal (sporadic type) or head and neck (endemic

type) tumor and can metastasize to the bone marrow or CNS.

DLBCL commonly manifests as either an abdominal or mediastinal primary and,

rarely, disseminates to the bone marrow or CNS.

ALCL manifests either as a primary cutaneous manifestation (10%) or as systemic

disease (90%) with dissemination to liver, spleen, lung, or mediastinum.

Bone marrow or CNS disease is rare in ALCL.

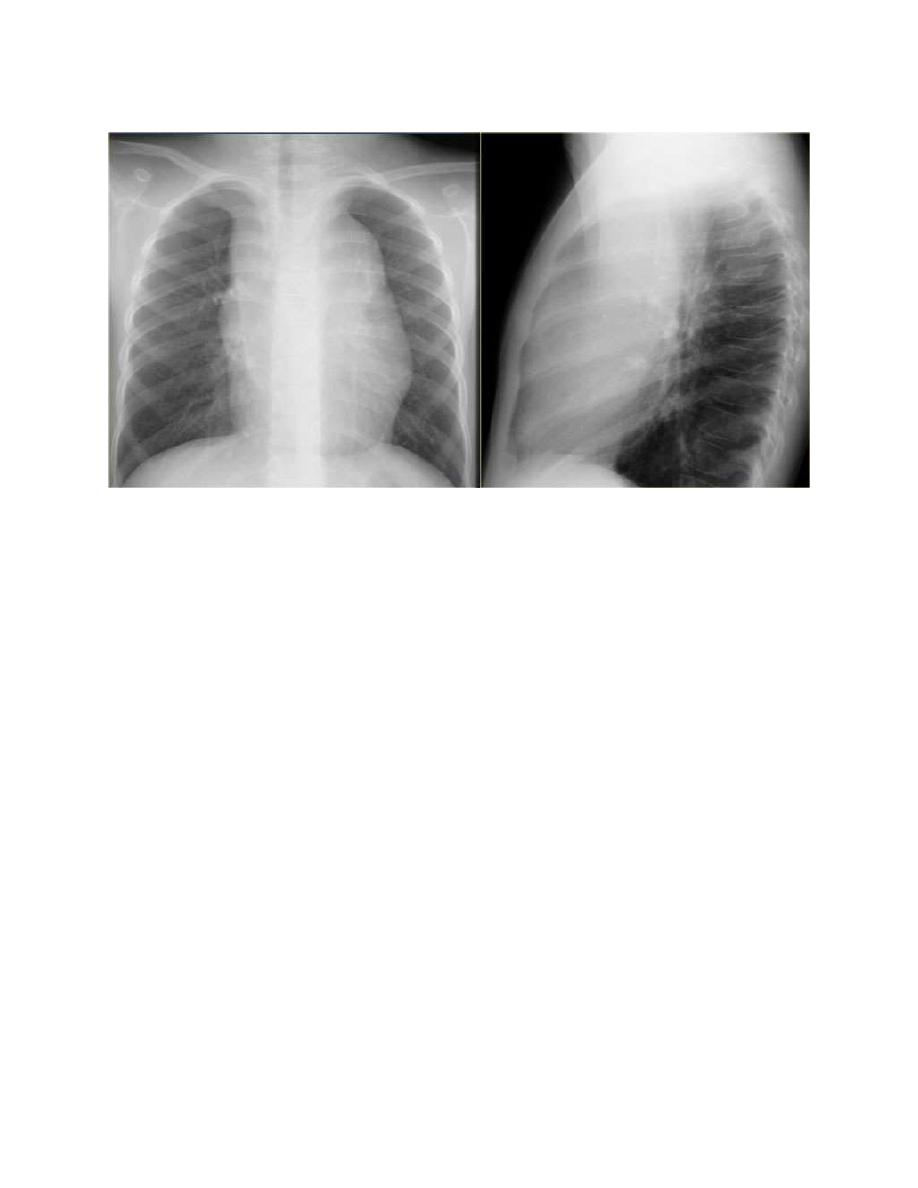

Site-specific manifestations of NHL include painless, rapid lymph node

enlargement; cough or dyspnea with thoracic involvement; superior mediastinal

syndrome; ascites, increased abdominal girth or intestinal obstruction with an

abdominal mass; nasal congestion, earache, hearing loss, or tonsil enlargement

with Waldeyer ring involvement; and localized bone pain. NHL can present as a

life-threatening oncologic emergency.

Superior mediastinal syndrome can occur as a consequence of a large mediastinal

mass causing obstruction of blood flow or respiratory airways.

8

Spinal cord tumors can cause cord compression and acute paraplegias requiring

emergent radiation therapy.

Tumor lysis syndrome (TLS) can occur from rapid cell turnover, which is especially

common in BL. TLS can result in severe metabolic abnormalities including

hyperuricemia, hyperphosphatemia, hyperkalemia, and hypocalcemia. This can

rapidly lead to renal insufficiency/failure as well as cardiac abnormalities if not

aggressively treated.

LABORATORY FINDINGS:

Recommended laboratory and radiologic testing includes complete blood cell

count; measurements of electrolytes, lactate dehydrogenase, uric acid, calcium,

phosphorus, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, bilirubin, alanine aminotransferase,

and aspartate aminotransferase; bone marrow aspiration and biopsy; lumbar

puncture with cerebrospinal fluid cytology, cell count and protein; chest

radiographs; and neck, chest, abdominal, and pelvic CT scans (head CT for

suspicion of CNS disease), and PET scan.

Tumor tissue (i.e., biopsy, bone marrow, cerebrospinal fluid, or

pleurocentesis/paracentesis fluid) should be tested by flow cytometry for

9

immunophenotypic origin (T, B, or null) and cytogenetics karyotype.

TREATMENT:

The treatment for childhood and adolescent NHL is multiagent systemic

chemotherapy with intrathecal chemotherapy .

Surgery is used mainly for diagnosis.

Radiation therapy is used only in special circumstances, such as CNS involvement

in LBL or, in the presence of acute superior mediastinal syndrome or paraplegias.

Newly diagnosed patients, especially those with BL and LBL, are at high risk for

TLS. These patients require vigorous hydration, frequent electrolyte monitoring,

and either a xanthine oxidase inhibitor (allopurinol, 10 mg/kg/day PO divided into

3 doses daily) or recombinant urate oxidase (rasburicase, 0.2 mg/kg/day IV once

daily for up to 5 days). Recombinant urate oxidase is preferred in patients with a

high risk of tumor lysis. Frequently, only a single dose is needed; however, repeat

doses can be given if a subsequent rise in uric acid is seen.

Pediatric BL and DLBCL are treated with similar chemotherapy regimens, which

are designed for mature B-NHL. Regimens vary based on stage and risk

stratification.

For patients with localized disease, multiagent chemotherapy is given over a 6 wk

to 6 mo period and the prognosis is excellent.

10

COMPLICATIONS:

Patients receiving multiagent chemotherapy for advanced disease are at acute risk

for serious mucositis, infections, cytopenias that require red blood cell and platelet

blood product transfusions, electrolyte imbalances, and poor nutrition.

Long-term complications include the risk of growth retardation, cardiac toxicity,

gonadal toxicity with infertility, and secondary malignancies.

PROGNOSIS:

The prognosis is excellent for most forms of childhood and adolescent NHL.

Patients with localized disease have a 90-100% chance of survival, and those with

advanced disease have a 70-95% chance of survival.

As outcomes for pediatric patients with NHL have improved substantially, the

focus has now shifted to minimizing the long-term toxicity of therapy.