Vulval cancers

Vulval cancer is uncommon, with an incidence of ten cases per 100 000

women .These are skin tumours of the vulva and are divided into HPV

associated (usually younger patients) and non-HPV (usually older

patients) cancers. The latter group may have their cancer associated with

VIN and lichen sclerosis,melanoma, pagets disease,smoking ,

immunosuppression.

Clinical presentation

Vulval cancers usually present with vulval symptoms. Patients may

present with a lump

(noticed when washing

), vulval pain (some tumours are

ulcerating) and post-menopausal bleeding (some tumours bleed

on touch). Some patients are frequently unaware of vulval cancer.

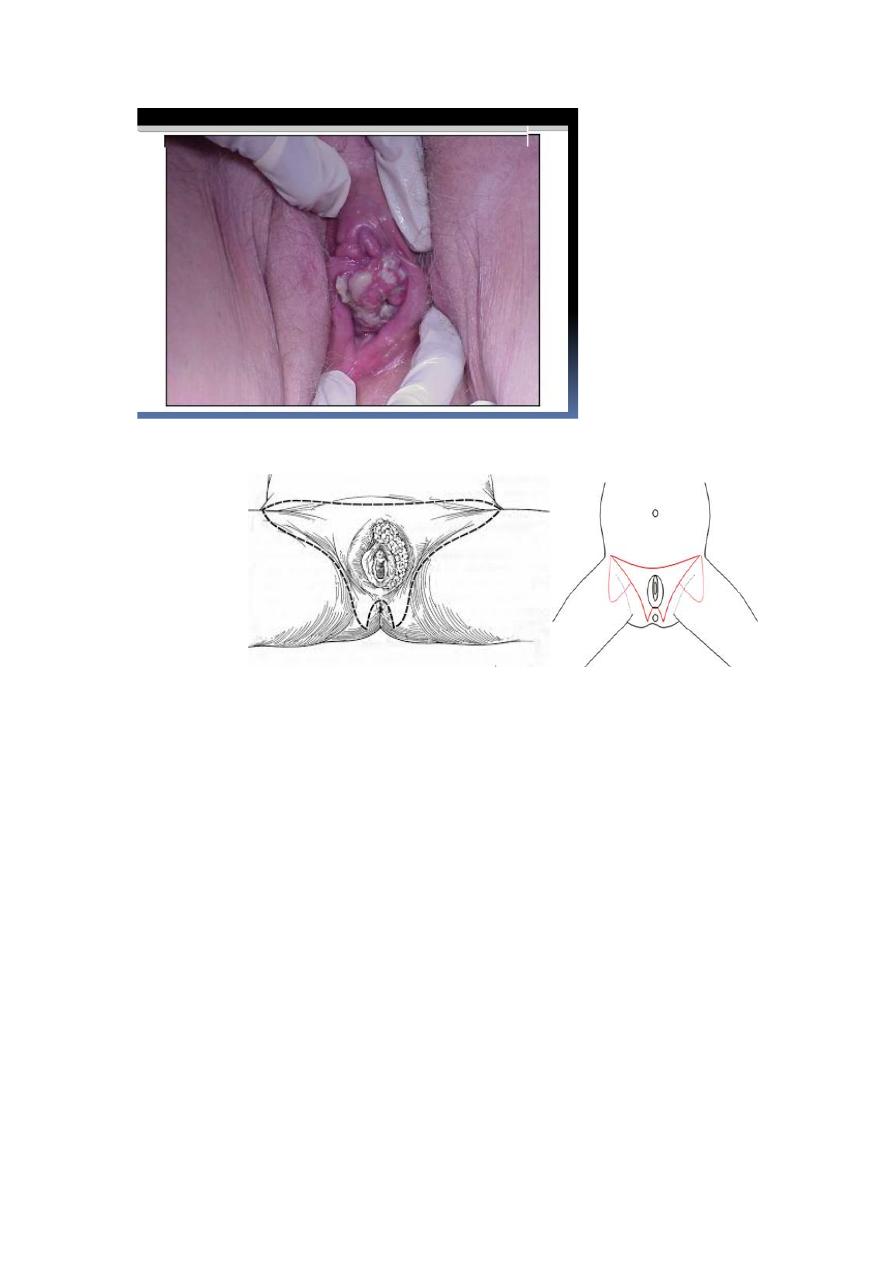

The tumours are usually clinically obvious and are often cauliflower-type

growths on the vulva.

The most common sites are the labia majora and clitoris and the tumours

may be uni- or multifocal so it is important to examine the patient

thoroughly (include the anal area, vagina and cervix). Vulval cancer

spreads regionally to the groin nodes (inguinal and femoral) and palpation

of these nodes is important to exclude clinically obvious malignant nodes.

Patients should also have the cervix inspected to make sure that there is

no involvement by cancer or cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN).

Pathophysiology

Most vulval cancers are squamous cell cancers of the skin. The lymphatic

drainage of the vulva (and the lower third of the vagina) is to the inguinal

and femoral lymph nodes and this is the first place to which the tumour

metastasizes. Beyond this, the tumour can spread up the lymphatic chain

and finally to the liver and lungs at a late stage.

Investigations:

A full-thickness biopsy should be taken from the tumour and should

include the interface between the apparent normal surrounding tissue and

the cancer. biopsy is essential for diagnosisThe cervix should be

visualized to exclude a cervical cancer, which may occasionally coexist..

chest x-ray is useful to exclude obvious lung metastases. a computed

tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance (MR) assessment of the pelvis

should be undertaken to exclude obvious pelvic lymphadenopathy.

Poor prognostic factors include:

large (greater than 4 cm) primary tumours, sphincter involvement and

metastases to the groin nodes.

Staging of vulval cancer

:

Stage Description 5-year survival

1 1a: Confined to vulva and/or perineum, 2 cm or less maximum

diameter. Groin nodes not palpable. Stromal invasion no greater than 1

mm

1b: As for 1a but stromal invasion >1 mm

2

Confined to vulva and/or perineum, more than 2 cm maximum

diameter. Groin nodes not palpable

3

Extends beyond the vulva, vagina, lower urethra or anus; or unilateral

regional lymph node metastasis

4

4a: Involves the mucosa of rectum or bladder upper urethra; or pelvic

bone; and/or bilateral regional lymph node metastases

4b: Any distant metastasis including pelvic lymph nodes

Treatment

Two broad categories of patient can be identified at the outset:

• Those who have small unifocal vulvar lesions with no clinical evidence

of nodal involvement.

• Those who have more advanced vulvar disease and or have clinical

evidence of nodal involvement.

For the purposes of further discussion, these will be termed as early and

late disease, respectively.

Surgical management of early vulvar cancer

Wide local excision is usually sufficient for the majority of lesions

between 1 and 10 mm in depth. Surgical excision should therefore be at

least 15 mm on all the tumour dimensions. In situations where for

example in early but midline cancers(clitoris, urethra, anus), radiotherapy

may have a role in allowing local control without loss of function

Surgical management of advanced vulvar lesions

advanced vulvar lesions indicates that wide local excision would either

be a radical vulvectomy and/or would compromise function.

The prime objective is to maximize local control, closely followed by

consideration of further function and cosmesis in that particular woman.

Management of lymph node:

In small ( < 2 cm) lateral tumours, only an ipsilateral groin node

dissection need initially be performed.

A lateralized lesion, is defined as one in which wide excision, at least 1

cm beyond the visible tumour edge, would not impinge upon a midline

structure

If the ipsilateral nodes are subsequently shown to be positive for cancer,

the contralateral nodes should also be excised or irradiated as the nodes

are more likely to be positive in this scenario.

For larger lateralized bilateral node dissection would be advisable.

En bloc and separate groin incisions

The need for en bloc removal of the lymph nodes has received

much attention, largely because it has been felt that this type of

procedure accounts for a significant pro portion of the morbidity

and that the technique employing separate groin incisions results

in a better cosmetic outcome.

The anxiety relating to the triple incision is the possibility of

relapse in the bridge of tissue left between the vulvectomy or local

excision and the groin nodes. Certainly if the lymphatic channels

contain malignant cells at the time of resection, then recurrence

would seem to be a real possibility. Current consensus would

suggest that en bloc dissection of the nodes is probably best

retained for large vulvar lesions and in situations where there is

gross involvement of the groin nodes-

Complications of surgery

.

1. Groin dissection

• Wound breakdown/cellulitis

• Lymphocyst

• Lymphoedema

2. Vulvar resection

• Wound breakdown/cellulitis

• Rectocoele

• Urinary problems

• Psychological

Patients with lymphoedema describe a heavy, ‘wooden’, sometimes

painful feeling in the legs as a result of retention of lymph fluid. This can

cause reduced mobility and problems wearing shoes. Management

involves leg elevation, good skin care, massage of the limbs and, in

severe cases, support stockings.

The sentinel lymph node (SLN) procedure:

may replace groin node dissection in the future where the SLN (the first

lymph node to be involved with metastases) is identified and removed in

isolation. If this node is negative, the patient is followed up and if

positive, radiotherapy is given.

Advanced disease (stages 3 and 4) is difficult as patients often die from

disease. Patients are treated with combinations of surgery (to remove

malignant nodes), radiotherapy and chemotherapy. This is as difficult

treatment as patients are often elderly and radiotherapy to the vulval skin

frequently produces pain through skin desquamation. Palliative care input

therefore is important at an early stage.