1

r

NEUROBLASTOMA:

Objective: To understand the clinical presentations , diagnosis , epidemiology ,

pathology , prognosis and treatment.

Neuroblastomas are embryonal cancers of the peripheral sympathetic nervous

system with heterogeneous clinical presentation and course, ranging from tumors

that undergo spontaneous regression to very aggressive tumors unresponsive to

very intensive multimodal therapy.

The causes of most cases remain unknown, and the outcomes for aggressive forms

of neuroblastoma remain poor.

EPIDEMIOLOGY:

Neuroblastoma is the most common extracranial solid tumor in children and the

most commonly diagnosed malignancy in infants.

Neuroblastoma accounts for >15% of the mortality from cancer in children.

The median age of children at diagnosis of neuroblastoma is 22 mo, and 90% of

cases are diagnosed by 5 yr of age.

The incidence is slightly higher in boys and in whites.

PATHOLOGY:

Neuroblastoma tumors, which are derived from neural crest cells, form a

spectrum with variable degrees of neural differentiation,ranging from tumors with

primarily undifferentiated small round cells (neuroblastoma) to tumors consisting

of mature and maturing Schwannian stroma with ganglion cells

(ganglioneuroblastoma or ganglioneuroma).

The tumors may resemble other small round blue cell tumors, such as

rhabdomyosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, and non- Hodgkin lymphoma.

The prognosis of children with neuroblastoma varies with the histologic features of

the tumor, and prognostic factors include the presence and amount of Schwannian

stroma, the degree of tumor cell differentiation, and the mitosis-karyorrhexis index.

PATHOGENESIS:

The etiology of neuroblastoma in most cases remains unknown.

Familial neuroblastoma accounts for 1-2% of all cases, is associated with a

younger age at diagnosis, and is linked to mutations in the PHOX2Band ALK

genes. The BARD1 gene has also been identified as a major genetic contributor to

neuroblastoma risk.

Neuroblastoma is associated with other neural crest disorders, including

Hirschsprung disease, central hypoventilation syndrome, and neurofibromatosis

type I, and potentially congenital cardiovascular malformations.

Children with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome and hemihypertrophy also have a

higher incidence of neuroblastoma.

Increased incidence of neuroblastoma is associated with some maternal and

paternal occupational chemical exposures, farming, and work related to

2

electronics,although no single environmental exposure has been shown to directly

cause neuroblastoma. Amplification of MYCN is strongly associated with

advanced tumor stage and poor outcomes.

Hyperdiploidy confers better prognosis if the child is younger than 1 yr of age at

diagnosis.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS:

The signs and symptoms of neuroblastoma reflect the tumor site and extent of

disease, and the symptoms of neuroblastoma can mimic many other disorders, a

fact that can result in a delayed diagnosis. Neuroblastoma may develop at any site

of sympathetic nervous system tissue. Approximately half of neuroblastoma

tumors arise in the adrenal glands, and most of the remainder originate in the

paraspinal sympathetic ganglia. Metastatic spread, which is more common in

children older than 1 yr of age at diagnosis, the most common sites of metastasis

are the regional or distant lymph nodes, long bones and skull, bone marrow, liver,

and skin. Lung and brain metastases are rare, occurring in >3% of cases.

Metastatic disease can cause a variety of signs and symptoms, including

fever,irritability, failure to thrive, bone pain, cytopenias, bluish subcutaneous

nodules, orbital proptosis, and periorbital ecchymoses.

Localized disease can manifest as an asymptomatic mass or can cause Paraspinal

neuroblastoma tumors can invade the neural foramina, causing spinal cord and

nerve root compression.

Neuroblastoma can also be associated with a paraneoplastic syndrome of

autoimmune origin, termed opsoclonus–myoclonus–ataxia syndrome, in which

patients experience rapid, uncontrollable jerking eye and body movements, poor

coordination,and cognitive dysfunction. Some tumors produce catecholamines that

can cause increased sweating and hypertension, and some release vasoactive

intestinal peptide, causing a profound secretory diarrhea. Children with extensive

tumors can also experience tumor lysis syndrome and disseminated intravascular

coagulation.

Infants younger than 1 yr of age also can present in unique fashion, termed stage

4S, with widespread subcutaneous tumor nodules, massive liver involvement,

limited bone marrow disease, and a small primary tumor without bone involvement

or other metastases.

DIAGNOSIS:

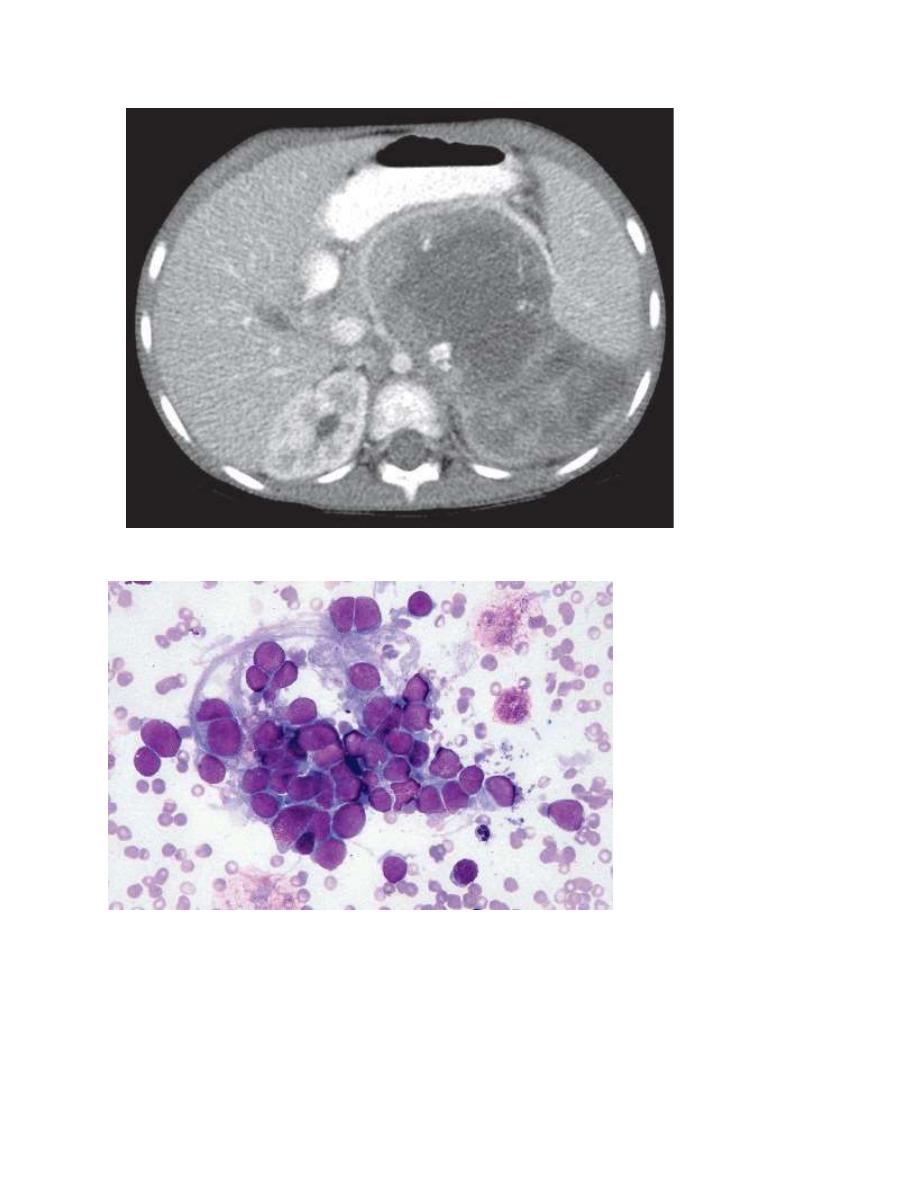

Neuroblastoma is usually discovered as a mass or multiple masses on plain

radiography, CT, or MRI . The mass often contains calcification and hemorrhage

that can be appreciated on plain radiography or CT.

Prenatal diagnosis of neuroblastoma on maternal ultrasound scans is sometimes

possible.

3

Tumor markers, including catecholamine metabolites homovanillic acid and

vanillylmandelic acid, are elevated in the urine of approximately 95% of cases and

help to confirm the diagnosis.

A pathologic diagnosis is established from tumor tissue obtained by biopsy.

Neuroblastoma can be diagnosed without a primary tumor biopsy if small round

blue tumor cells are observed in bone marrow samples and the levels of

vanillylmandelic acid or homovanillic acid are elevated in the urine.

Evaluations for metastatic disease should include CT or MRI of the chest and

abdomen, bone scans to detect cortical bone involvement,and at least 2

independent bone marrow aspirations and biopsies to evaluate for marrow disease.

MRI of the spine should be performed in cases with suspected spinal cord

compression, but imaging of the brain with either CT or MRI is not routinely

performed unless indictated by the clinical presentation.

ed with Neuroblastoma

.

.

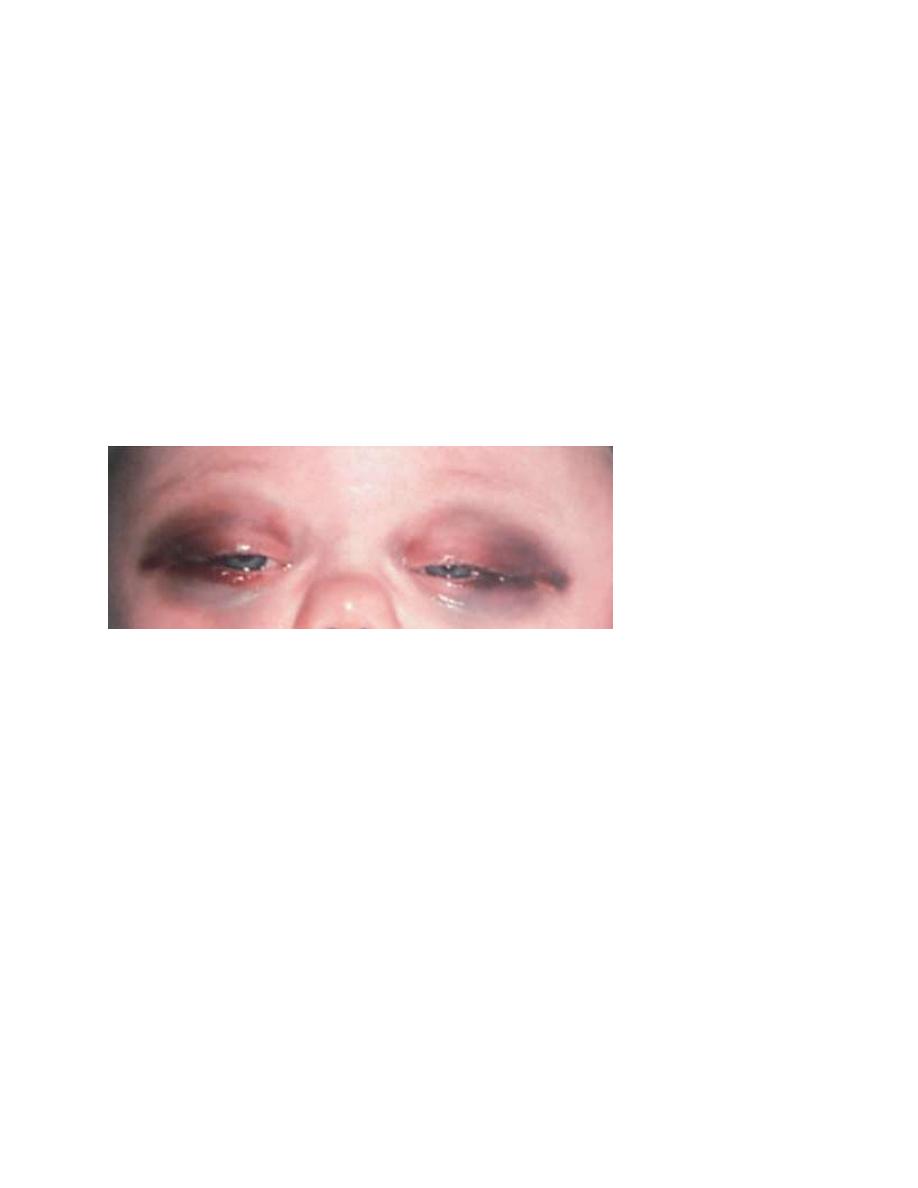

Periorbital metastases of neuroblastoma with ecchymoses and proptosis.

4

T

able 498-3

International

Neuroblastoma

Staging System

5

The International Neuroblastoma Staging System (INSS) is currently used to

stage patients with neuroblastoma after initial surgical resection .

Stage 1 tumors are confined to the organ or structure of origin and are completely

resected.

Stage 2 tumors extend beyond the structure of origin but not across the midline,

either with (stage 2B) or without (stage 2A) ipsilateral lymph node involvement.

Stage 3 tumors extend beyond the midline, with or without bilateral lymph node

involvement.

Stage 4 tumors are disseminated, with metastases to bones, bone marrow, liver,

distant lymph nodes, and other organs.

Stage 4S refers to neuroblastoma in children younger than 1 yr of age with

dissemination to liver, skin, and/or bone marrow without bone involvement and

with a primary tumor that would otherwise be staged as stage 1 or 2.

TREATMENT:

The patient’s age and tumor stage are combined with cytogenetic and molecular

features of the tumor to determine the treatment risk group and estimated prognosis

for each patient .

The usual treatment for children with low-risk neuroblastoma is surgery for stages

1and 2 and observation for stage 4S with cure rates generally >90% without further

therapy.

Children with spinal cord compression at diagnosis also may require urgent

treatment with chemotherapy, surgery, or radiation to avoid neurologic damage.

Stage 4S neuroblastomas have a very favorable prognosis, and many regress

spontaneously without therapy. Chemotherapy or resection of the primary tumor

does not improve survival rates, but for infants with massive liver involvement and

respiratory compromise, small doses of cyclophosphamide or low-dose hepatic

irradiation may alleviate symptoms. For children with stage 4S neuroblastoma who

require treatment for symptoms, the survival rate is 81%.

Treatment of intermediate-risk neuroblastoma includes surgery ,chemotherapy,

and, in some cases, radiation therapy. The chemotherapy usually includes

moderate doses of cisplatin or carboplatin, cyclophosphamide,etoposide, and

doxorubicin given for several months. Radiation therapy is used for tumors with

incomplete response to chemotherapy. Children with intermediate-risk

neuroblastoma,including children with stage 3 disease and infants with stage 4

disease and favorable characteristics, have an excellent prognosis and >90%

survival with this moderate treatment.

Children with high-risk neuroblastoma have long-term survival rates between 25%

and 35% with current treatment that consists of intensive chemotherapy, high-dose

chemotherapy with autologous stem cell rescue, surgery, radiation, and 13-cis-

retinoic acid . Induction chemotherapy for children with high-risk neuroblastoma

6

includes combinations of cyclophosphamide, topotecan, doxorubicin, vincristine,

cisplatin, and etoposide.

After completion of induction chemotherapy, resection of the residual primary

tumor is followed by high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell rescue

and focal radiation therapy to tumor sites.

Cases of high-risk neuroblastoma are associated with frequent relapses, and

children with recurrent neuroblastoma have a <50% response rate to alternative

chemotherapy regimens.

Wilms Tumor:

Wilms tumor (WT), also known as nephroblastoma, is the most common primary

malignant renal tumor of childhood.

It is the second most common malignant abdominal tumor in childhood.

The most common sites of metastases are the lungs, regional lymph nodes, and

liver.

Histologically, the classic WT is made up of varying proportions of blastemal,

stromal, and epithelial cells, recapitulating stages of normal renal development.

The treatment includes surgery and chemotherapy with or without radiotherapy.

The use of the current, multimodality treatment has dramatically improved the cure

rate of WT from <30% to approximately 90% .

EPIDEMIOLOGY:

WT accounts for 6% of pediatric malignancies and more than 95% of kidney

tumors in children. Approximately 75% of the cases occur in children younger

than 5 yr with a peak incidence at 2-3 yr of age. It can arise in 1 or both kidneys;

the incidence of bilateral WTs is 7%. Most cases are sporadic, but approximately

2% of patients have a family history. In 8-10% of patients, WT is observed in the

context of hemihypertrophy, aniridia, genitourinary anomalies, and a variety of

rare syndromes, including Beckwith- Wiedemann syndrome and Denys-Drash

syndrome .An earlier age of diagnosis and an increased incidence of bilateral

disease are generally observed in syndromic and familial cases.

ETIOLOGY: GENETICS AND MOLECULAR BIOLOGY:

WT is thought to be derived from incompletely differentiated renal mesenchyme,

and tumors are typically composed of the undifferentiated and partially

differentiated cells that normally arise from renal mesenchyme.

Foci of benign, undifferentiated mesenchyme (nephrogenic rests) that persist

abnormally in the kidney into postnatal life are observed in approximately 1% of

children in the general population, but are present in up to 90% of children who

have a family history of WT, develop bilateral tumors, or display features of WT-

related syndromes.

7

Nephrogenic rests usually regress or differentiate ,but those that persist can

become malignant.

Genetic mutations have been detected in a third of WTs ,located on chromosome

11 .

Germline mutations are usually associated with WT in the context of genitourinary

anomalies or the WAGR (Wilms, aniridia, genitourinary anomalies, mental

retardation) syndrome.

WT is occasionally observed in families with a predisposition to

pleuropulmonary blastoma, with mutations of the gene, located at 14q31.are

observed in these families. A family history of WT is noted in approximately 2%

of WT patients, and predisposition is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait with

incomplete penetrance.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION:

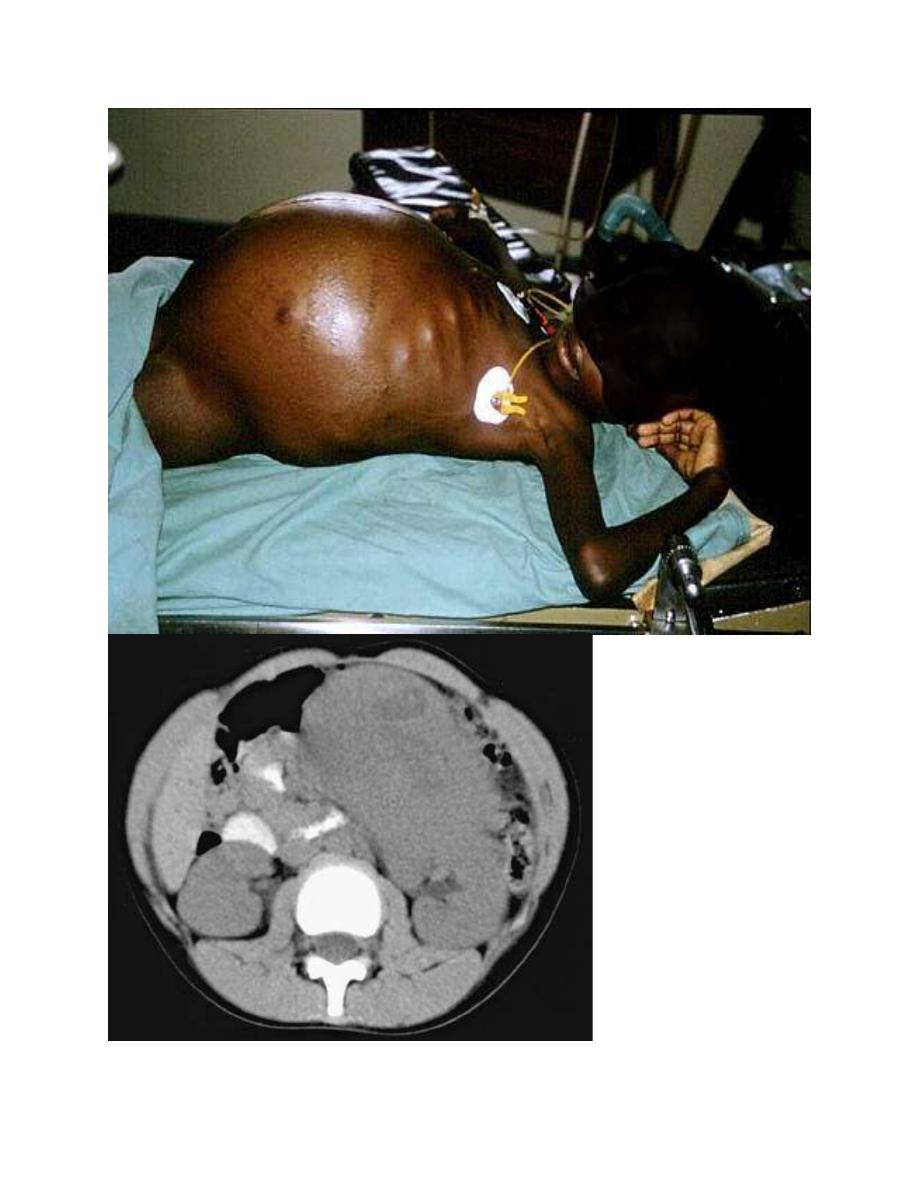

The most common initial clinical presentation for WT is the incidental discovery

of an asymptomatic abdominal mass by parents while bathing or clothing an

affected child or by a physician during a routine physical examination.

Functional defects in paired organs like the kidney, with good functional reserve,

are also unlikely to be detected early. Hypertension is present in approximately

25% of tumors at presentation and has been attributed to increased renin activity.

Abdominal pain, gross painless hematuria, and fever are other frequent findings

at diagnosis. Occasionally, rapid abdominal enlargement and anemia occur as a

result of bleeding into the renal parenchyma or pelvis. WT thrombus extends into

the inferior vena cava in 4-10% of patients, and rarely into the right atrium.

Patients might also have microcytic anemia from iron deficiency or anemia of

chronic disease, polycythemia, elevated platelet count, and acquired deficiency of

von Willebrand factor or factor VII deficiency.

4 Staging of mor

Stage I Tumor confined to the kidney and completely resected. Renal capsule or

sinus vessels not involved. Tumor not ruptured or biopsied. Regional lymph nodes

examined and negative.

Stage II Tumor extends beyond the kidney but is completely resected with

negative margins and lymph nodes. At least 1 of the following has occurred: (a)

penetration of renal capsule, (b) invasion of renal sinus vessels.

Stage III Residual tumor present following surgery confined to the abdomen,

including gross or microscopic tumor; spillage of tumor preoperatively or

intraoperatively; biopsy prior to nephrectomy, regional lymph node metastases;

tumor implants on the peritoneal surface; extension of tumor thrombus into the

inferior vena cava including thoracic vena cava and heart.

Stage IV Hematogenous metastases (lung, liver, bone, brain, etc.) or lymph node

metastases outside the abdominopelvic region.

Stage V Bilateral renal involvement by tumor.

8

9

DIAGNOSIS AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS:

An abdominal mass in a child should be considered malignant until diagnostic

imaging, laboratory findings, and pathology can define its true nature.

Imaging studies include plain abdominal radiography, abdominal ultrasonography,

and CT of the abdomen to define the intrarenal origin of the mass and differentiate

it from adrenal masses (e.g., neuroblastoma) and other masses in the abdomen.

Abdominal ultrasonography helps differentiate solid from cystic masses. WT

might show focal areas of necrosis or hemorrhage and hydronephrosis caused by

obstruction of the renal pelvis by the tumor. Ultrasonography with Doppler

imaging of renal veins and the inferior vena cava is a useful first study that not

only can look for WT but also can evaluate the collecting system and demonstrate

tumor thrombi in the renal veins and inferior vena cava.

CT is useful to define the extent of the disease, integrity of the contralateral kidney,

and metastasis.

MRI requires sedation in young children and is not routinely used; it may be

helpful in defining an extensive tumor thrombus that extends up to the level of the

hepatic veins or even into the right atrium, and to distinguish WT from

nephrogenic rests.

Chest CT is more sensitive than chest radiography to screen for pulmonary

metastasis, and is preferably performed before surgery because effusions and

atelectasis can confound the interpretation of postoperative imaging studies.

A bone scan is performed if the histologic diagnosis confirms clear cell sarcoma

of the kidney to look for bone metastasis.

Regional spread and metastatic lesions can be visualized on positron emission

tomography( PET )/CT scanning.

The diagnosis is usually made by imaging studies and confirmed by histology at

the time of nephrectomy.

Although biopsy is a reliable diagnostic tool, it is discouraged as it results in

disease upstaging.

A core needle biopsy obtained via a posterior approach should be performed in

cases of unusual presentation (older age, signs of infection, inflammation) or

unusual imaging findings (significant adenopathy, no renal parenchyma seen,

intratumoral calcification).

10

TREATMENT:

There are 2 major schools of thought in the management of WT, the first

recommends surgery prior to initiating treatment and the second recommends

preoperative chemotherapy. Each approach has advantages and limitations but they

have similar outcomes. Early surgery provides accurate diagnosis and staging, and

can facilitate risk-adapted therapy. Preoperative chemotherapy can make surgery

easier and reduces the risk of intraoperative tumor rupture and hemorrhage.

Surgery entails a radical nephrectomy with meticulous dissection to avoid rupture

of the tumor capsule and lymph node sampling despite the absence of abnormal

nodes on preoperative imaging studies or intraoperative assessment.

Partial nephrectomy is performed in patients with bilateral disease or with

unilateral WT and a predisposing syndrome such as Denys-Drash and WAGR, so

as to minimize the risk of future renal failure.

Prognostic factors for risk-adapted therapy include age, stage, tumor weight, and

loss of heterozygosity at chromosomes 1p and 16q. Histology plays a major role in

risk stratification of WT. Absence of anaplasia is considered a favorable histologic

finding but presence of anaplasia is further classified as focal or diffuse, both of

which are unfavorable histologic findings.

Patients with favorable histologic findings of WT have a good outcome and are

generally treated in the outpatient setting.

Nephrectomy alone may be sufficient for patients younger than 2 yr of age with

stage I disease and a tumor weighing <550 g.

Patients with stages I and II disease receive chemotherapy with 2 drugs,

vincristine and actinomycin D ( dactinomycin), every 1-3 wk for a total of 18 wk .

Patients with stage III or IV disease receive chemotherapy with 3 drugs

(vincristine, doxorubicin, and actinomycin D) every 1-3 wk for a total of 24 wk

and radiation therapy.

Patients with regional lymph node metastases, residual disease after surgery, or

tumor rupture receive radiation therapy to the flank or abdomen, and those with

lung metastases receive radiation therapy to the lungs.

Anaplastic histology (focal and diffuse) accounts for approximately 11% of WT

cases.

Patients with diffuse anaplasia, in particular, have a poor outcome & treated with

intensive chemotherapy regimens that include vincristine, cyclophosphamide,

doxorubicin, etoposide, carboplatin, and ifosfamide, in addition to radiation

therapy.

11

RECURRENT DISEASE:

Approximately 15% of WT patients with favorable histology and 50% of those

with anaplastic histology suffer relapse; most relapses occur early (within 2 yr of

diagnosis).

Factors associated with a favorable outcome after relapse include low stage (I/II)

at diagnosis, treatment with vincristine and actinomycin D only, no prior

radiotherapy, favorable histology, relapse to lung only, and interval from

nephrectomy to relapse 12 mo or longer.

Patients with recurrent WT who previously received only vincristine and

actinomycin D had a 4 yr survival of approximately 80%, whereas those who

previously received the 3 drug regimen of vincristine, actinomycin D, and

doxorubicin had a 4 yr survival of only 50%.

Other agents used to treat recurrent WT include doxorubicin, carboplatin,

cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide, etoposide, and topotecan.

Metachronous WT may not represent tumor relapse but instead may indicate

development of a new tumor in the opposite kidney.

PROGNOSIS:

Despite some adverse risk factors that decrease prognosis (metastases, unfavorable

histology, recurrent disease, and loss of heterozygosity of both 1p and 16q), most

children with WT have a very favorable prognosis.

Overall, the survival of children with WT approaches 90%, with some prognostic

factors (low stage, favorable histology, young age, low tumor weight) conferring

even better outcomes.

LATE EFFECTS:

Late complications are a consequence of treatment type and intensity; the use of

radiotherapy and anthracyclines increases the risk of these complications.

Clinically significant late sequelae include musculoskeletal effects, cardiac

toxicity, pulmonary disease, reproductive problems

,

renal dysfunction, and the

development of second malignant neoplasms.