1

Organophosphorus insecticides and nerve agents

Organophosphorus compounds are widely used as pesticides,

especially in developing countries. Case fatality following deliberate

ingestion is high (5–20%). Nerve agents, developed for chemical

warfare, are derived from OP insecticides and are much more toxic.

They are commonly classified as G (originally synthesised in Germany)

or V (‘venomous’) agents. The ‘G’ agents, such as tabun, sarin and

soman, are volatile, absorbed by inhalation or via the skin, and

dissipate rapidly after use. ‘V’ agents, such as VX, are contact poisons

unless aerosolised, and contaminate ground for weeks or months. The

toxicology and management of nerve agent and pesticide poisoning are

similar.

Mechanism of toxicity

OP compounds inactivate acetylcholinesterase (AChE), resulting in the

accumulation of acetylcholine (ACh) in cholinergic synapses. Initially,

spontaneous hydrolysis of the OP–enzyme complex allows reactivation

of the enzyme but, subsequently, loss of a chemical group from the OP–

enzyme complex prevents further enzyme reactivation. After this

process (termed ‘ageing’) has taken place, new enzyme needs to be

synthesised before function can be restored. The rate of ‘ageing’ is an

important determinant of toxicity and especially rapid after exposure to

nerve agents (soman in particular), which cause ‘ageing’ within

minutes.

Clinical features and management

OP poisoning causes an acute cholinergic phase, which may

occasionally be followed by the intermediate syndrome or

2

organophosphate-induced delayed polyneuropathy (OPIDN). The onset,

severity and duration of poisoning depend on the route of exposure

and agent involved.

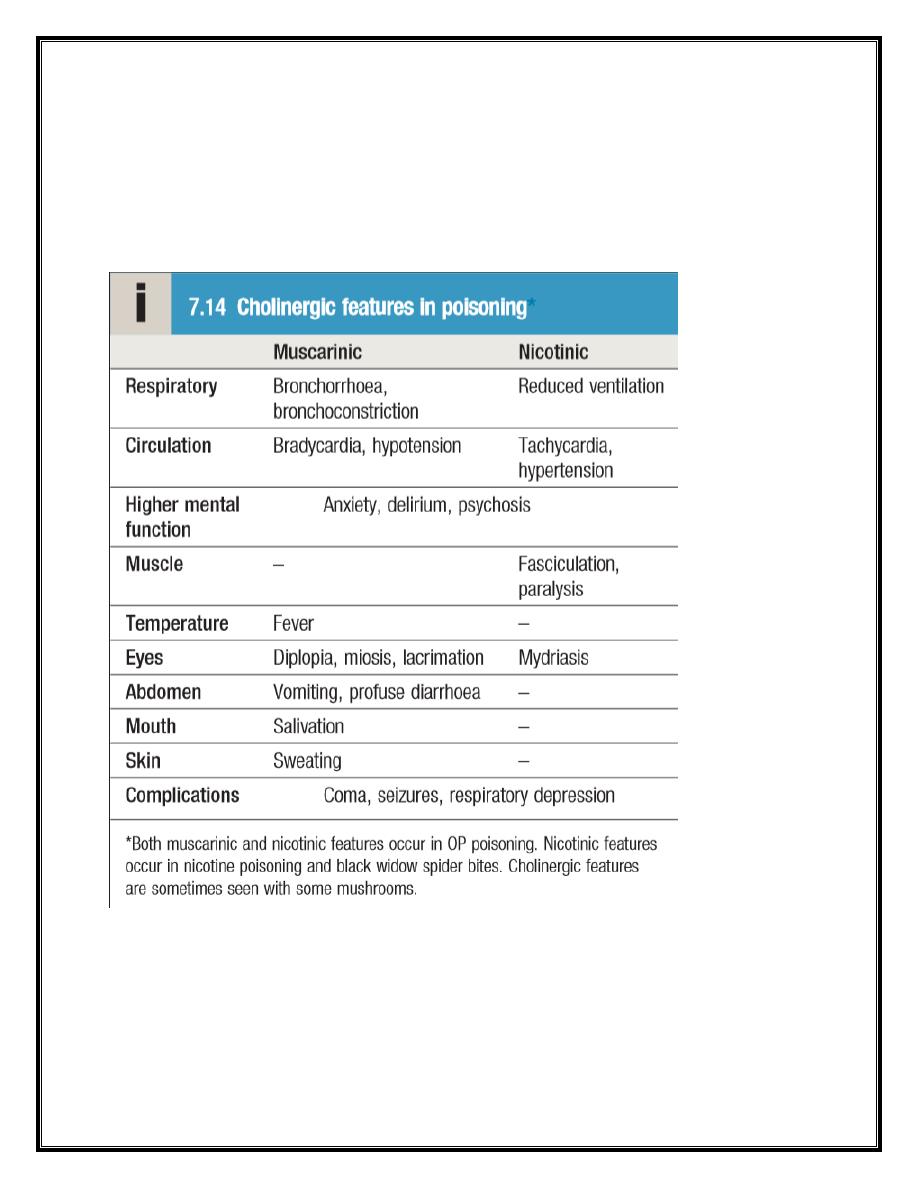

Acute cholinergic syndrome

This usually starts within a few minutes of exposure and nicotinic or

muscarinic features may be present. Vomiting and profuse diarrhoea

are typical following ingestion. Bronchoconstriction, bronchorrhoea and

salivation may cause severe respiratory compromise. Excess sweating

3

and miosis are characteristic and the presence of muscular

fasciculations strongly suggests the diagnosis, although this feature is

often absent, even in serious poisoning. Subsequently, generalised

flaccid paralysis may develop and affect respiratory and ocular muscles,

resulting in respiratory failure. Ataxia, coma, convulsions, cardiac

repolarisation abnormalities and torsades de pointes may occur.

Management

The airway should be cleared of excessive secretions, breathing and

circulation assessed, high-flow oxygen administered and intravenous

access obtained. Appropriate external decontamination is needed.

Gastric lavage or activated charcoal may be considered if the patient

presents sufficiently early. Seizures should be treated. The ECG, oxygen

saturation, blood gases, temperature, urea and electrolytes, amylase

and glucose should be monitored closely. Early use of sufficient doses

of atropine is potentially life-saving in patients with severe toxicity.

Atropine reverses ACh-induced bronchospasm, bronchorrhoea,

bradycardia and hypotension. When the diagnosis is uncertain, a

marked increase in heart rate associated with skin flushing after a 1 mg

intravenous dose makes OP poisoning unlikely. In OP poisoning,

atropine (2 mg IV) should be administered and this dose should be

doubled every 5–10 minutes until clinical improvement occurs. Further

bolus doses should be given until secretions are controlled, the skin is

dry, blood pressure is adequate and heart rate is > 80 bpm. Large doses

may be needed, but excessive doses may cause anticholinergic effects.

In severe poisoning requiring atropine, an oxime such as pralidoxime

chloride or obidoxime is generally recommended, if available, although

efficacy is debated. This may reverse or prevent muscle weakness,

4

convulsions or coma, especially if given rapidly after exposure. Oximes

reactivate AChE that has not undergone ‘ageing’ and are therefore less

effective with dimethyl compounds and nerve agents, especially soman.

Oximes may provoke hypotension, especially if administered rapidly.

Intravenous magnesium sulphate has been reported to increase

survival in animals and in small human studies of OP poisoning;

however, further clinical trial evidence is needed before this can be

recommended routinely. Ventilatory support should be instituted

before the patient develops respiratory failure. Benzodiazepines may

be used to treat agitation, fasciculations and seizures and for sedation

during mechanical ventilation. Exposure is confirmed by measurement

of plasma or red blood cell cholinesterase activity but antidote use

should not be delayed pending results. Plasma cholinesterase is

reduced more rapidly but is less specific than red cell cholinesterase.

Values correlate poorly with the severity of clinical features but are

usually < 10% in severe poisoning, 20–50% in moderate poisoning and >

50% in subclinical poisoning. The acute cholinergic phase usually lasts

48–72 hours, with most patients requiring intensive cardiorespiratory

support and monitoring. Cholinergic features may be prolonged over

several weeks with some lipid-soluble agents.

Intermediate syndrome

About 20% of patients with OP poisoning develop weakness that

spreads rapidly from the ocular muscles to those of the head and neck,

proximal limbs and the muscles of respiration, resulting in ventilatory

failure. This ‘intermediate syndrome’ generally develops 1–4 days after

exposure, often after resolution of the acute cholinergic syndrome, and

may last 2–3 weeks. There is no specific treatment and supportive care

is needed, including maintenance of airway and ventilation.

5

Organophosphate-induced delayed polyneuropathy

Organophosphate-induced delayed polyneuropathy (OPIDN) is a rare

complication that usually occurs 2–3 weeks after acute exposure. It is a

mixed sensory/motor polyneuropathy, affecting long myelinated

neurons especially, and appears to result from inhibition of enzymes

other than AChE. Early clinical features are muscle cramps followed by

numbness and paraesthesiae, proceeding to flaccid paralysis of the

lower and subsequently the upper limbs, with foot and wrist drop and a

high-stepping gait, progressing to paraplegia. Sensory loss may also be

present but is variable. Initially, tendon reflexes are reduced or lost but

mild spasticity may develop later. There is no specific therapy for

OPIDN. Regular physiotherapy may limit deformity caused by muscle-

wasting. Recovery is often incomplete and may be limited to the hands

and feet, although substantial functional recovery after 1–2 years may

occur, especially in younger patients.

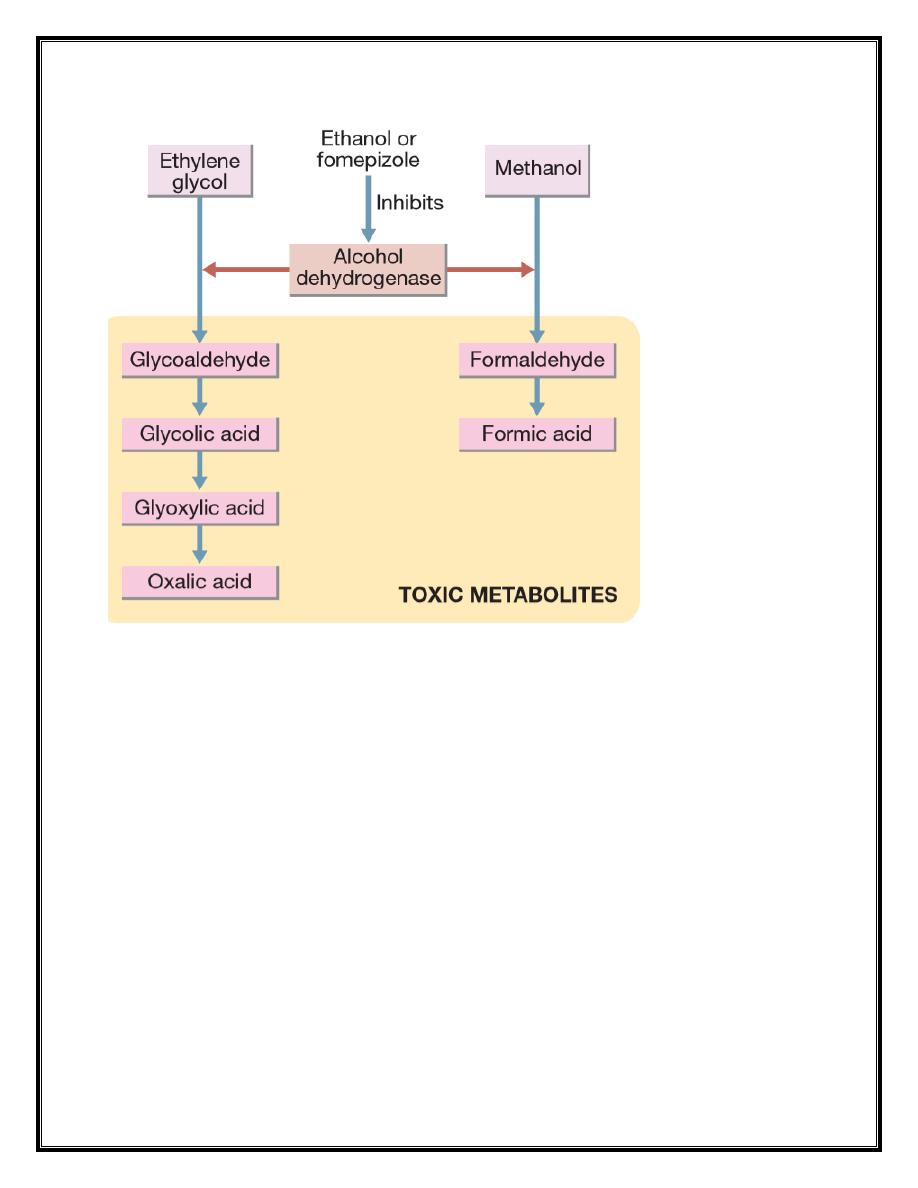

Methanol and ethylene glycol

Ethylene glycol is found in antifreeze, brake fluids and, in lower

concentrations, windscreen washes. Methanol is present in some

antifreeze products and commercially available industrial solvents, and

in low concentrations in some screen washes and methylated spirits. It

may also be an adulterant of illicitly produced alcohol. Both are rapidly

absorbed after ingestion. Methanol and ethylene glycol are not of high

intrinsic toxicity but are converted via alcohol dehydrogenase to toxic

metabolites that are largely responsible for their clinical effects.

6

Clinical features

Early features of poisoning with either methanol or ethylene glycol

include vomiting, ataxia, drowsiness, dysarthria and nystagmus. As toxic

metabolites are formed, metabolic acidosis, tachypnoea, coma and

seizures may develop. Toxic effects of ethylene glycol include

ophthalmoplegia, cranial nerve palsies, hyporeflexia and myoclonus.

Renal pain and acute tubular necrosis occur because of renal calcium

oxalate precipitation. Hypocalcaemia, hypomagnesaemia and

hyperkalaemia are common. Methanol poisoning causes headache,

delirium and vertigo. Visual impairment and photophobia develop,

associated with optic disc and retinal oedema and impaired pupil

reflexes. Blindness may be permanent, although some recovery may

7

occur over several months. Pancreatitis and abnormal liver function

have also been reported.

Management

Urea and electrolytes, chloride, bicarbonate, glucose, calcium,

magnesium, albumin, plasma osmolarity and arterial blood gases

should be measured in all patients with suspected methanol or

ethylene glycol toxicity. The osmolar and anion gaps should be

calculated. Initially, poisoning is associated with an increased osmolar

gap, but as toxic metabolites are produced, an increased anion gap

develops, associated with metabolic acidosis. The diagnosis can be

confirmed by measurement of ethylene glycol or methanol

concentrations but assays are not widely available. An antidote, ideally

fomepizole but otherwise ethanol, should be administered to all

patients with suspected significant exposure while awaiting the results

of laboratory investigations. These block alcohol dehydrogenase and

delay the formation of toxic metabolites until the parent drug is

eliminated in the urine or by dialysis. The antidote should be continued

until ethylene glycol or methanol concentrations are undetectable.

Metabolic acidosis should be corrected with sodium bicarbonate (e.g.

250 mL of 1.26% solution, repeated as necessary). Convulsions should

be treated with an intravenous benzodiazepine. In ethylene glycol

poisoning, hypocalcaemia should be corrected only if there are severe

ECG features or if seizures occur, as this may increase calcium oxalate

crystal formation. In methanol poisoning, folinic acid should be

administered to enhance the metabolism of the toxic metabolite,

formic acid. Haemodialysis or haemodiafiltration should be used in

severe poisoning, especially if renal failure is present or there is visual

loss in the context of methanol poisoning. It should be continued until

8

acute toxic features are no longer present and ethylene

glycol/methanol concentrations are undetectable.