1

THI QAR U. MEDICAL COLLEGE LECTURES 2017

DEPARTMENT OF INTERNAL MEDICINE Dr. FAEZ KHALAF, SUBSPACIALITY GIT

Primary biliary cirrhosis

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is a

chronic, progressive cholestatic liver

disease that predominantly

affects middle-aged women.

It is strongly associated with the presence of antimitochondrial antibodies

(AMA),

which are

diagnostic,

And is characterised by a granulomatous inflammation of the portal tracts, leading to progressive

damage and eventually loss of the small and middle-sized bile ducts.

This in turn leads to fibrosis and cirrhosis of the liver.

The condition typically presents with an insidious onset of itching and/or tiredness;

It may also be found incidentally as the result of routine blood tests.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of PBC varies across the world.

It is

relatively common in northern Europe

and North America but is rare in Africa and Asia.

There is a

strong female to- male predominance of 9 :1

it is also

more common amongst cigarette smokers

.

Clustering of cases has been reported, suggesting an environmental trigger in susceptible individuals.

Pathophysiology

Immune mechanisms are clearly involved. The condition is closely associated with other autoimmune no

hepatic diseases, such as

thyroid disease

, and there is a genetic association with

HLA-DR8

AMA are directed at pyruvate dehydrogenase complex

, a mitochondrial enzyme complex that plays a key role

in cellular energy generation.

PBC-specific ANA

(such as those directed at the nuclear pore antigen gp210) have a characteristic staining

pattern in immunofluorescence assays (selectively binding to the nuclear rim or nuclear dots), which means

that they should not be mistaken for the homogenously staining ANA seen in AIH.

Elevations in serum immunoglobulin levels are frequent but, unlike in AIH,

elevation is typically of IgM

.

AMA , IgM, ANA

Pathologically

chronic granulomatous inflammation

destroys the interlobular bile ducts

progressive lymphocyte-mediated inflammatory damage

Causes fibrosis, which spreads from the portal tracts to the liver parenchyma and

eventually leads to

cirrhosis

.

2

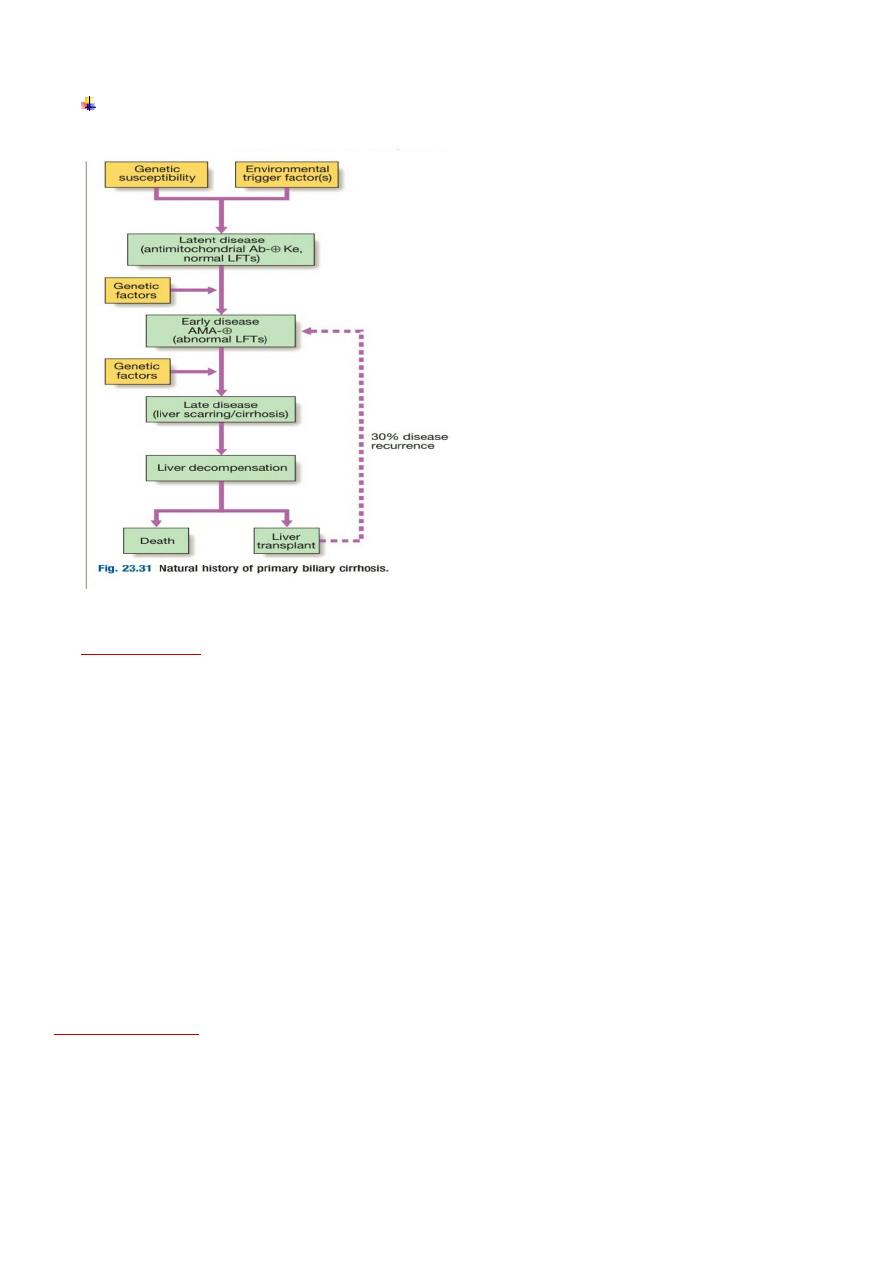

Natural history of primary biliary cirrhosis.

Clinical features

1. Systemic symptoms such as fatigue are common and may precede diagnosis for years.

2. Pruritus, which can be a feature of any cholestatic disease, is a common presenting complaint and

may precede jaundice by months or years.

3. Jaundice is rarely a presenting feature.

4. The itching is usually worse on the limbs.

5. Although there may be right upper abdominal discomfort, fever and rigors do not occur.

6. Bone pain or fractures can rarely result from Osteomalacia (fat-soluble vitamin malabsorption) or,

more commonly, from osteoporosis (hepatic osteodystrophy).

7. Initially, patients are well nourished but weight loss can occur as the disease progresses.

8. Scratch marks may be found in patients with severe pruritus.

9. Jaundice is only prominent late in the disease and can become intense.

10. Xanthomatous deposits occur in a minority, especially around the eyes.

11. Mild hepatomegaly is common and splenomegaly becomes increasingly common as portal

hypertension develops.

12. Liver failure may supervene

Associated diseases

1. Sicca syndrome

2. systemic sclerosis

3. coeliac disease

4. thyroid diseases.

Hypothyroidism should always be considered in patients with fatigue.

3

Diagnosis and investigations

The LFTs show a pattern of cholestasis

(Hypercholesterolemia is common and worsens as disease progresses; however, it is of no diagnostic value.

AMA is present in over 95% of patients

, and when it is absent the diagnosis should not be made without

obtaining histological evidence and considering cholangiography

(MRCP or ERCP) to exclude other biliary

disease

.

ANA and anti-smooth muscle antibodies are present in around 15% of patients

Ultrasound examination shows no sign of biliary obstruction.

Liver biopsy is only necessary if there is diagnostic uncertainty. The histological features of

PBC correlate poorly with the clinical features;

portal hypertension can develop before the histological onset of cirrhosis.

Management

The hydrophilic bile acid, ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), at a dose of 13–15 mg/kg/day improves bile flow,

replaces toxic hydrophobic bile acids in the bile acid pool, and reduces apoptosis of the biliary epithelium.

Clinically, UDCA improves LFTs, may slow down histological progression and has few side -effects it is

therefore widely used in the treatment of PBC and should be regarded as the optimal first-line treatment.

A significant minority of patients either fail to normalize their LFTs with UDCA or show an inadequate

response, and such patients have an increased risk of developing end-stage liver disease compared to

patients showing a full response.

There is currently no consensus as to how to treat such patients. Immunosuppressants, such as

corticosteroids, azathioprine, penicillamine and ciclosporin, have all been trialled in PBC.

Liver transplantation should be considered once liver failure has developed and may be indicated in patients

with intractable pruritus.

Serum bilirubin remains the most reliable marker of declining liver function. Transplantation is associated

with an excellent 5-year survival of over 80%,

although the disease will recur in over one third of patients at 10 years.

Pruritus

This is the main symptom requiring treatment. The cause is unknown but up-regulation of opioid receptors

and increased levels of endogenous opioids may play a role. First-line treatment is with the anion-binding

resin

cholestyramine

,

which probably acts by binding potential pruritogens in the intestine and increasing

their excretion in the stool. A dose of 4–16 g/day orally is used. The powder is mixed in orange

juice and the main dose (8 g) taken before and after breakfast, when maximal duodenal bile acid

concentrations occur.

Cholestyramine may bind other drugs in the gut (most obviously, UDCA), and adequate spacing should be

used between drugs. Cholestyramine is sometimes ineffective, especially in complete biliary obstruction, and

can be difficult for some patients to tolerate.

Alternative treatments include

rifampicin

(150 mg/day, titrated up to a maximum of 600 mg/day as required

and contingent on there being no deterioration in LFTs),

naltrexone

(an opioid antagonist; 25 mg/day initially, increasing up to 300 mg/day),

plasmapheresis and a liver support device (e.g. a molecular adsorb recirculating system

(MARS)).

Fatigue

Fatigue affects about

one-third

of patients with PBC.

The cause is unknown but it may reflect intracerebral changes due to cholestasis.

Unfortunately, once

depression, hypothyroidism and coeliac disease have been

excluded, there is currently no specific treatment.

The impact on patients’ lives can be substantial.

4

Malabsorption

Prolonged cholestasis is associated with steatorrhea and malabsorption of fat-soluble

vitamins, which should be replaced as necessary. Coeliac disease should be excluded since

its incidence is increased in PBC.

Bone disease

Osteopenia and osteoporosis are common, and normal post-menopausal bone loss is

accelerated.

Baseline bone density should be measured and treatment

started with replacement

calcium and vitamin D3.

Bisphosphonates should be used if there is evidence of osteoporosis.

Osteomalacia is rare.

Overlap syndromes

AMA-negative PBC (‘autoimmune cholangitis’)

A few patients demonstrate the clinical, biochemical and histological features of PBC but do not have

detectable AMA in the serum.

Serum transaminases, serum Ig levels and titres of ANA tend to be higher than in AMA positive PBC.

However, the clinical course mirrors classical PBC and these patients should be considered to have a variant

of PBC

PBC/autoimmune hepatitis overlap

A few patients with AMA and cholestatic LFTs have elevated transaminases, high serum immunoglobulins

and interface hepatitis on liver histology; in such individuals a trial of corticosteroid therapy may be

beneficial.

Primary sclerosing cholangitis

(PSC) is a

cholestatic liver disease caused by diffuse inflammation and fibrosis;

it can involve the entire biliary tree and leads to the gradual obliteration of intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts,

and ultimately biliary cirrhosis, portal hypertension and hepatic failure.

Although considered as an autoimmune disease, evidence for an autoimmune pathophysiology is weaker than is the

case for PBC and autoimmune hepatitis. The incidence is about

6.3/100 000

in Caucasians.

Cholangiocarcinoma develops in about 10–30% of patients during the course of the disease.

PSC is twice as common in young men.

Most patients present at age

25–40

years, although the condition

may be diagnosed at any age and is an

important cause of chronic liver disease in children

.

The generally accepted diagnostic criteria are:

1.

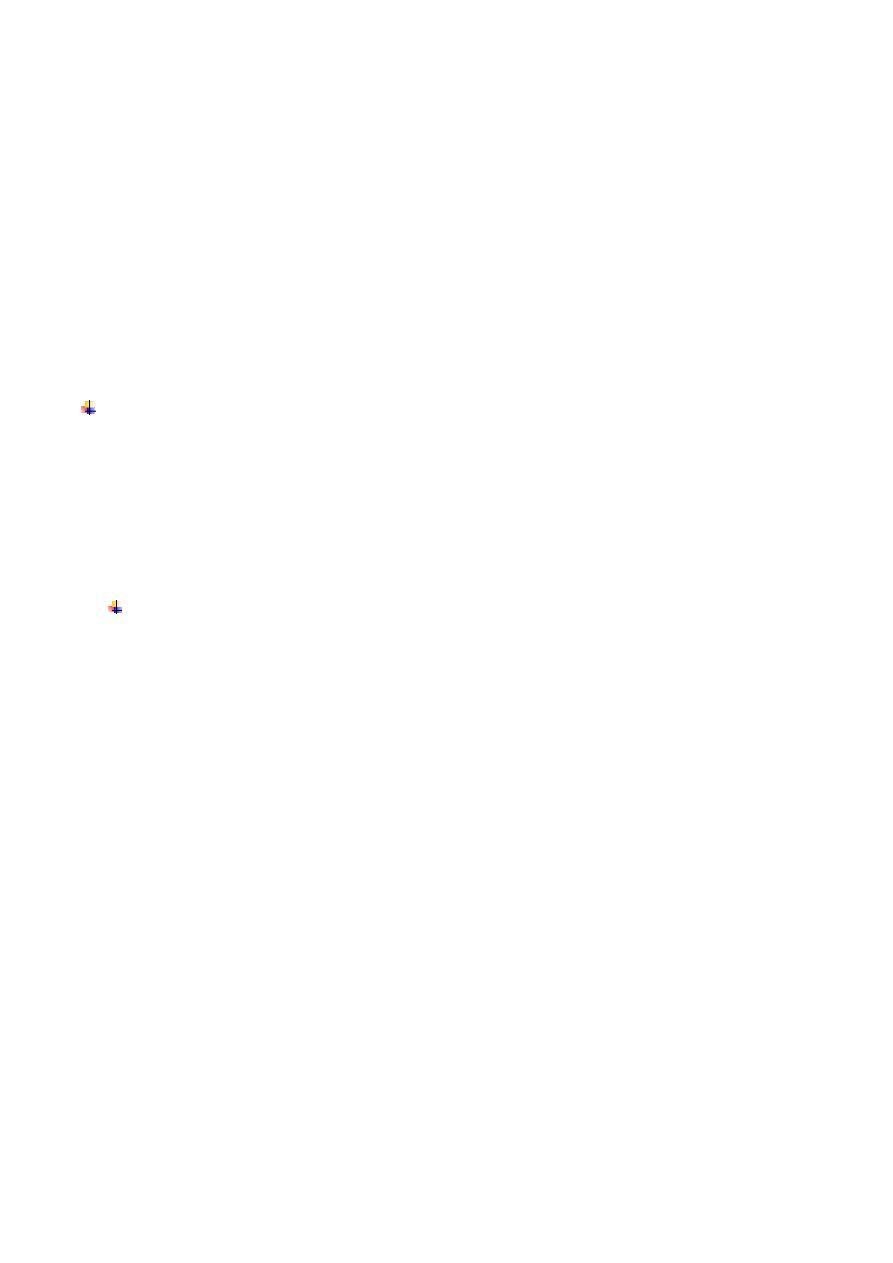

generalized beading and stenosis of the biliary system on cholangiography (Fig. 23.32)

2.

absence of choledocholithiasis (or history of bile duct surgery)

3.

exclusion of bile duct cancer, by prolonged follow-up.

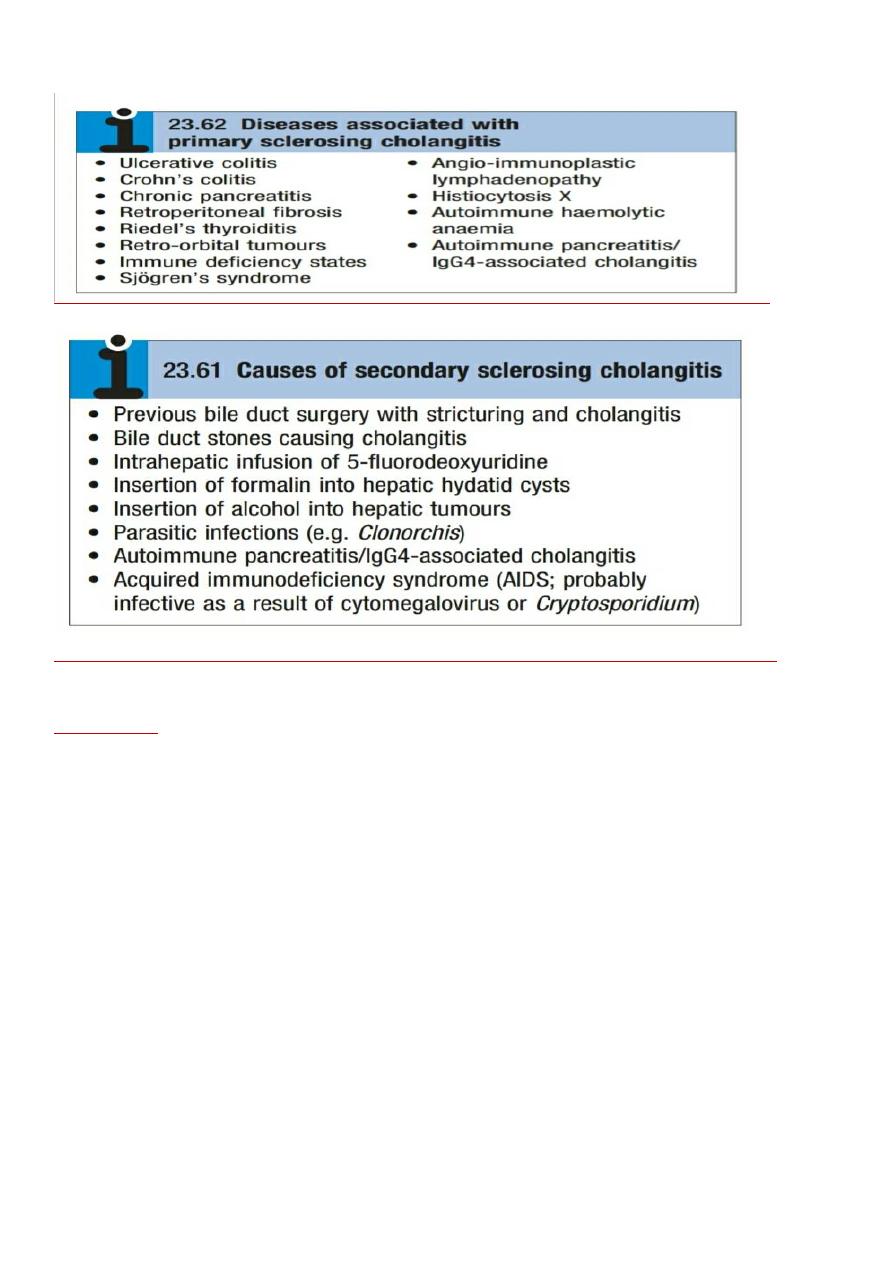

The term ‘secondary sclerosing cholangitis’ is used to describe the typical bile duct changes described above

when a clear predisposing factor for duct fibrosis can be identified.

The causes of secondary sclerosing cholangitis

5

Pathophysiology

The cause of PSC is unknown but there is a close association with

IBD particularly ulcerative colitis

. About

two-thirds

of patients have coexisting ulcerative colitis, and

PSC is the most common form of chronic liver

disease in ulcerative colitis

.

Between

3% and 10% of patients

with ulcerative colitis develop PSC, particularly those with extensive colitis

or pancolitis.

The prevalence of primary sclerosing cholangitis is lower in patients with Crohn’s colitis (about 1%).

Patients with

PSC and ulcerative colitis are at greater risk of colorectal neoplasia than those with ulcerative

colitis alone

, and those who develop colorectal neoplasia are at greater risk of Cholangiocarcinoma.

It is currently believed that PSC is an immunologically mediated disease, triggered in genetically susceptible

individuals by toxic or infectious agents, which may gain access to the biliary tract through a leaky, diseased

colon.

A close link with HLA haplotype A1 B8

DR3 DRW52A has been identified.

Perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA)

have been detected in the

sera of

60–80% of patients with PSC with or without ulcerative colitis, and in 30–40% of patients with

ulcerative colitis alone.

The antibody is not specific for PSC and is found in other chronic liver diseases

(e.g. 50% of patients with

autoimmune hepatitis

Clinical features

The diagnosis is often made incidentally when persistently raised serum ALP is discovered in an individual

with ulcerative colitis. Common symptoms include

fatigue, intermittent jaundice, weight loss, right upper quadrant abdominal pain and pruritus.

Attacks of acute cholangitis are uncommon and usually follow biliary instrumentation.

Physical examination is abnormal in about 50% of symptomatic patients; the most

common findings are

jaundice and hepatomegaly/splenomegaly.

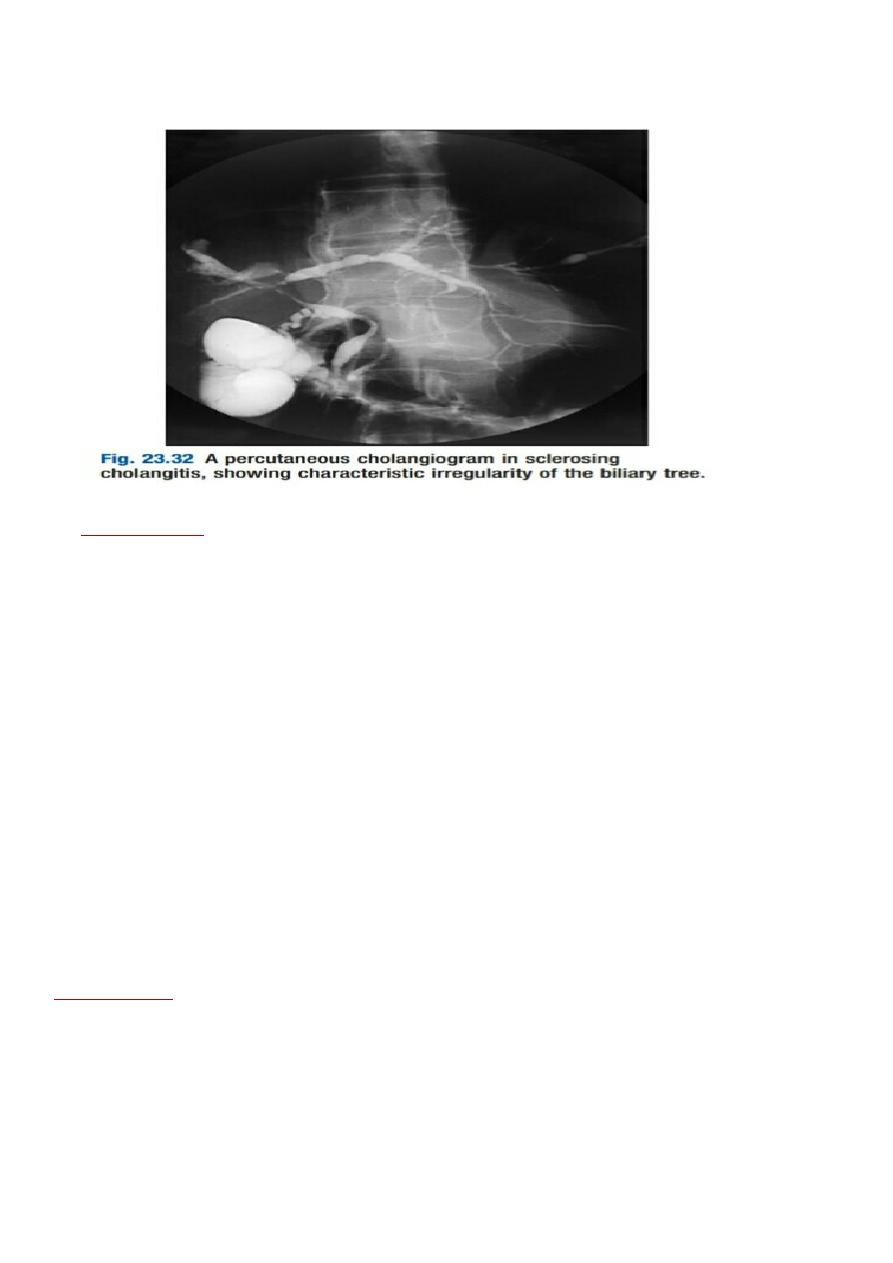

The condition may be associated with many other diseases

6

Investigations

Biochemical screening usually reveals

a cholestatic pattern of LFTs

but ALP and bilirubin levels may vary

widely in individual patients during the course of the disease.

For example, ALP and bilirubin values increase during acute cholangitis, decrease after therapy, and

sometimes fluctuate for no apparent reason.

Modest elevations in serum transaminases are usually seen, whereas hypoalbuminemia and clotting

abnormalities are found only at a late stage.

In addition to ANCA, low titres of serum ANA and anti-smooth muscle antibodies may be found in PSC but

have no diagnostic significance;

serum AMA is absent

.

The key investigation is now

MRCP,

which is usually diagnostic,

revealing multiple irregular stricturing and

dilatation .

ERCP should be reserved for patients in whom therapeutic intervention is likely to be necessary and should

follow MRCP.

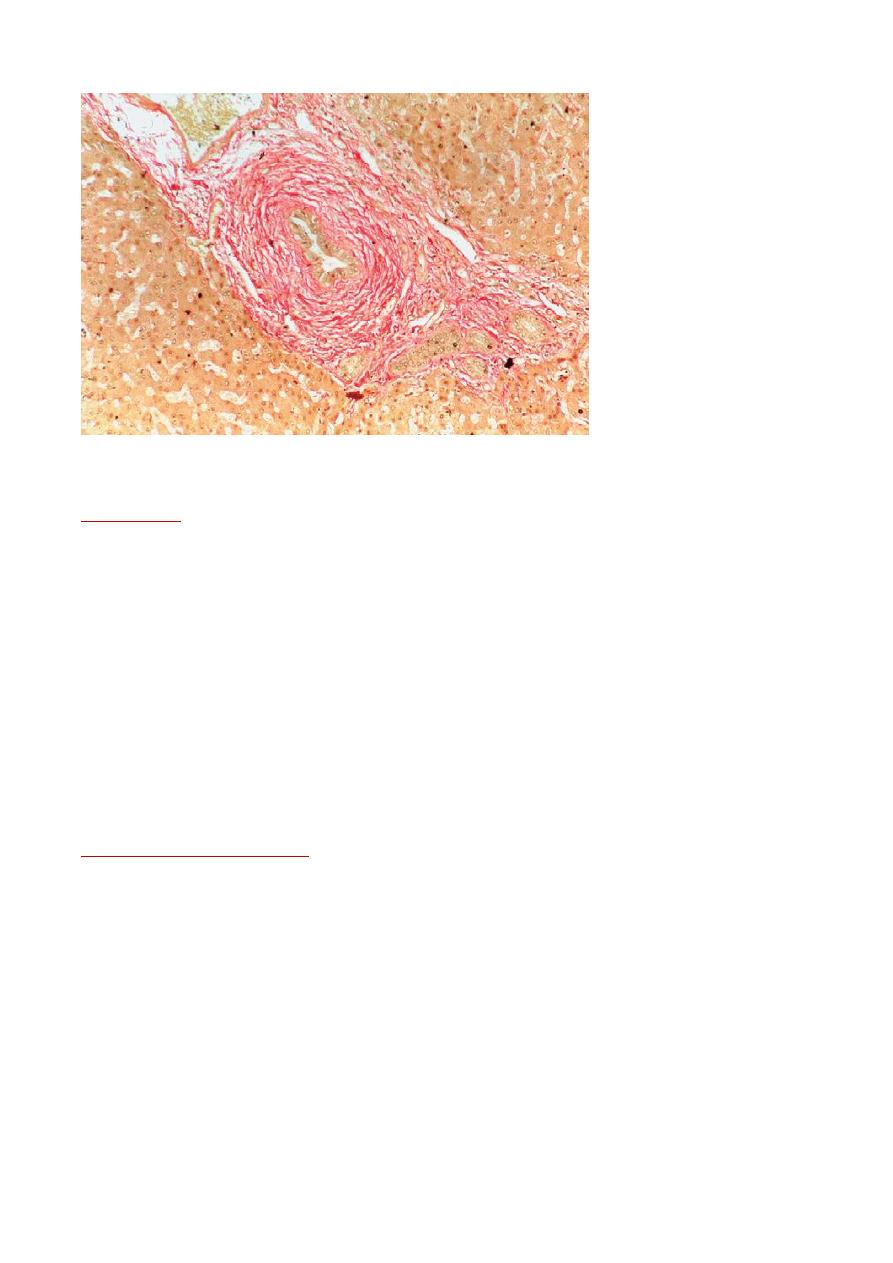

On liver biopsy the characteristic early features of PSC are periductal ‘

onion-skin’

fibrosis and inflammation,

with portal oedema and bile ductular proliferation resulting in expansion of the portal tracts .

Later, fibrosis spreads, progressing inevitably to biliary cirrhosis; obliterative cholangitis leads to the so -

called

‘vanishing bile duct syndrome’

.

7

Management

There is

no cure for PSC

, but management of cholestasis and its complications and specific treatment of the

disease process are indicated. UDCA is widely used, although the evidence to support this is limited.

UDCA

may have benefit in terms of reducing colon carcinoma risk.

The course of PSC is variable. In symptomatic patients, median survival from presentation to death or liver

transplantation is about 12 years.

About

75% of asymptomatic patients survive 15 years or more

.

Most patients die from liver failure

, about

30% die from bile duct carcinoma

, and the remainder die from

colonic cancer or complications of colitis.

Immunosuppressive agents, including prednisolone, azathioprine, methotrexate and ciclosporin, have been

tried; generally, results have been disappointing.

Symptomatic patients often have pruritus. Management is as for PBC. Fatigue appears to be less prominent

than in PBC, although it is still present in some patients.

Management of complications

Broad-spectrum antibiotics (e.g.

ciprofloxacin

) should be given for

acute attacks of cholangitis

but have no

proven value in preventing attacks.

If cholangiography shows a well-defined obstruction to the extrahepatic bile ducts

(‘dominant stricture’), mechanical relief can be obtained by placement of a plastic stent or by balloon

dilatation performed at ERCP.

It is important, in this situation, actively to consider the possibility

Cholangiocarcinoma (the differential

diagnosis for dominant extrahepatic stricture).

Fat-soluble vitamin replacement is necessary in jaundiced patients.

Metabolic bone disease (

usually osteoporosis

) is a common complication that requires treatment

Primary sclerosing cholangitis. Note onion-skin scarring arrows) surrounding a bile duct.

8

Surgical treatment

Surgical resection of the extrahepatic bile duct and biliary reconstruction have a

limited role in the

management of non-cirrhotic patients with dominant extrahepatic disease.

Orthotropic transplantation is the only surgical option in patients with advanced liver disease;

5-year

survival is 80–90% in most centres.

Unfortunately, the condition may recur in the graft and there are no identified therapies able to

prevent this.

Cholangiocarcinoma is a contraindication to transplantation.

Colon carcinoma risk can be increased in patients following transplant

because of the

effects of immune suppression .

IgG4-associated cholangitis

This recently reported disease is closely related to autoimmune pancreatitis

(which is present in more than 90% of the patients. IgG4-associated cholangitis

(IAC)

often presents with

obstructive jaundice (due to either hilar structuring/

intrahepatic sclerosing cholangitis

or a low bile duct

stricture), and Cholangiographic appearances suggest PSC with or without hila Cholangiocarcinoma.

The

serum IgG4 is often raised and liver biopsy shows a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, with IgG4-positive

plasma cells

. An important observation is that, compared to PSC,

IAC appears to respond well to steroid therapy